Introduction

Understanding how organisations work together to address large-scale goals is an important objective for contemporary society (Weber, Weidner, Kroeger, & Wallace, Reference Weber, Weidner, Kroeger and Wallace2017). Collaborative leadership has been advocated by many (Chrislip, Reference Chrislip2002; Chrislip & Larson, Reference Chrislip and Larson1994; Crosby & Bryson, Reference Crosby and Bryson2005, Reference Crosby and Bryson2010; Huxham & Vangen, Reference Huxham and Vangen2000; Kramer & Crespy, Reference Kramer and Crespy2011; Kramer, Day, Nguyen, Hoelscher, & Cooper, Reference Kramer, Day, Nguyen, Hoelscher and Cooper2019; Müller-Seitz & Sydow, Reference Sydow, Windeler, Schubert and Möllering2012; Sydow, Lerch, Huxham, & Hibbert, Reference Sydow, Lerch, Huxham and Hibbert2011) to be a suitable response to concerns of such magnitude. While recent research (Deken, Berends, Gemser, & Lauche, Reference Deken, Berends, Gemser and Lauche2018; Zuzul, Reference Zuzul2019) has examined interorganisational collaborations, our research suggests that exploring collaborative work from a deeper ‘leadership as process’ perspective (Hosking, Reference Hosking1988; Knights & Willmott, Reference Knights and Willmott1992; Parry, Reference Parry2004, Reference Parry1998; Sutherland, Land, & Böhm, Reference Sutherland, Land and Böhm2014) can uncover important antecedents that influence the success of such endeavours. This includes power dynamics, which are often overlooked in collaborative leadership research (Denis, Langley, & Sergi, Reference Denis, Langley and Sergi2012). Conversely, research on power dynamics within collaborations does not always give attention to leadership implications (Lotia, Reference Lotia2004; Suseno & Ratten, Reference Suseno and Ratten2007; Williams, Whiteman, & Parker, Reference Williams, Whiteman and Parker2019; Zhang & Guler, Reference Zhang and Guler2020).

By uncovering these antecedents, we extend existing interorganisational collaborative leadership theory (namely the work of Huxham and Vangen, Reference Huxham and Vangen2000) by proposing a process model that accounts for the sources of power that create patterns of influence across organisations and the hierarchical nature of relationships that result. This provides important learning for future efforts that require leadership from multiple organisations to achieve significant goals. We also answer the call for greater attention to power and leadership in interorganisational collaborations (Zuzul, Reference Zuzul2019).

Our research brings together three sets of scholarship: collaborative leadership, leadership as process and interorganisational work. We draw these together by using Bourdieu (Reference Bourdieu, Szeman and Kaposy1986) forms of capital to understand the sources of power that influence the leadership processes during collaborative activities. By doing so, our findings demonstrate that when deliberately seeking to practice interorganisational collaborative leadership, there needs to be an understanding of how prior relationships impact patterns of influence across the collaborating individuals and organisations. Social capital must be given specific attention as it can lead to power imbalances and the emergence of structures of exclusion. Thus, Bourdieu (Reference Bourdieu, Szeman and Kaposy1986) three forms of capital (economic, social and cultural) are key sources of power that must be recognised in any examination and practice of interorganisational collaborative leadership. This enables us to uncover the important power mechanisms inherent in any collaborative exercise but is often missing from research on interorganisational collaborative leadership.

Our study focuses on a network of organisations that deliberately intended to practice collaborative leadership in the development and delivery of a performing arts festival. We analysed data from an Australian-based multinational multicultural arts venture that included organisations from 22 countries in the Asia-Pacific region and staged 280 events over 4 months. We take a grounded theory approach (Corbin & Strauss, Reference Corbin and Strauss2008; Glaser & Strauss, Reference Glaser and Strauss1967) in order to incorporate ‘the complexities of the organisation(s) under investigation without discarding, ignoring, or assuming away relevant variables’ (Kan & Parry, Reference Kan and Parry2004: 470). This is particularly relevant given Parry (Reference Parry1998) assertion that grounded theory is very useful in exploring leadership as a social process.

Our findings suggest that collaborative leadership across organisations is more complex than is often depicted in the literature; with the possible exception of Liddle (Reference Liddle2018) and Eden and Huxham (Reference Eden and Huxham2001). While the group central to our study aimed to practice a collaborative leadership approach, what emerged was a model of collaborative leadership that we have termed ‘leadership by cavea’. We use this frame to explain how pre-existing relationships and power imbalances across the three capitals appeared to create a three-tiered social hierarchy amongst the participating organisations.

We contribute to existing research in several ways. First, we extend the collaborative leadership literature to include interorganisational collaborative leadership, recognising the power mechanisms that are often missing in this research and provide the needed empirical evidence. Second, we contribute to the leadership as process literature by elucidating a process model of interorganisational collaborative leadership that recognises the role Bourdieu's capitals play as sources of power for influence and leadership. Third, we contribute to the interorganisational collaboration literature by examining how leadership can develop over the period of a collaborative exercise, again giving attention to how Bourdieu's capitals structure the leadership relationships.

Literature review

Collaborative leadership has a more collective orientation, with leadership as something beyond that of an individual leader (Denis, Langley, & Sergi, Reference Denis, Langley and Sergi2012). It has received comparatively less attention with research more focused on public and nonprofit contexts such as government (Connelly, Reference Connelly2007; Curnin & O'Hara, Reference Curnin and O'Hara2019; Eden & Huxham, Reference Eden and Huxham2001; Forester & McKibbon, Reference Forester and McKibbon2020; Holbrook, Reference Holbrook2020; Huxham & Vangen, Reference Huxham and Vangen2000; Liddle, Reference Liddle2018; Vangen, Hayes, & Cornforth, Reference Vangen, Hayes and Cornforth2015) and education (Hallinger & Heck, Reference Hallinger and Heck2010; Liu, Bellibaş, & Gümüş, Reference Liu, Bellibaş and Gümüş2021; Torres, Reference Torres2019). To extend this research, we take collaborative leadership as a narratively constructed term that we investigate from a social process perspective.

Collaborative leadership as social process

Our research draws on the view of collaborative leadership from Sydow et al., (Reference Sydow, Lerch, Huxham and Hibbert2011) and the notion of ‘structuration’ (Giddens, Reference Giddens1984). That is, ‘the deliberate and emergent structuring of social systems such as formal organisations and regional clusters through structure guiding and structure reproducing practices’ (Sydow et al., Reference Sydow, Lerch, Huxham and Hibbert2011: 329). It is from this perspective that we can explore the ‘becoming’ of leadership within the process, rather than just the ‘being’ (Tsoukas & Chia, Reference Tsoukas and Chia2002) and uncover the subtle relations, appreciating its socially constructed nature (Fairhurst & Grant, Reference Fairhurst and Grant2010). We take Hosking's (Reference Hosking1988) view of leadership as a socially constructed process. Hence we suggest that collaborative leadership processes are manifested over time within interorganisational work. In this sense, our own research explores the event (Deleuze, Reference Deleuze1993) of an intended ‘interorganisational collaborative leadership’ exercise over time and from multiple perspectives to enable us to see the internal ‘milieu’ (Deleuze, Reference Deleuze1994) of an interorganisational collaborative venture.

Interorganisational collaborative leadership and capital as power

Interorganisational collaboration is defined by Hardy, Phillips, and Lawrence (Reference Hardy, Phillips and Lawrence2003: 323) as ‘a cooperative, interorganisational relationship that is negotiated in an on-going communicative process, and which relies on neither market nor hierarchical mechanisms of control’. Interorganisational collaboration often takes the form of strategic alliances, networks, joint ventures and consortia. In the present study, the central organising form referred to itself as a consortium. A consortium can be defined as ‘collective structures among formal equals’ (Sydow et al., Reference Sydow, Windeler, Schubert and Möllering2012: 912). As will be demonstrated in our findings, this definition did not fit the group of organisations under study.

As mentioned, what is often missing from research on interorganisational collaboration is a consideration of leadership and an awareness of the power dynamics across collaborative parties. For example Hardy, Phillips, and Lawrence (Reference Hardy, Phillips and Lawrence2003) discuss the role influence plays in the process of collaboration but do not discuss influence in the context of leadership. Others also look at other phenomena as part of the collaborative process such as learning (Huxham & Hibbert, Reference Huxham and Hibbert2008) and power (Tello-Rozas, Pozzebon, & Mailhot, Reference Tello-Rozas, Pozzebon and Mailhot2015; Zhang & Guler, Reference Zhang and Guler2020) but do not acknowledge the social processes of collaborative leadership. Drawing from the definitions provided by several authors discussed (Denis, Langley, & Sergi, Reference Denis, Langley and Sergi2012; Hardy, Phillips, & Lawrence, Reference Hardy, Phillips and Lawrence2003; Huxham & Vangen, Reference Huxham and Vangen2000; Müller-Seitz & Sydow, Reference Sydow, Windeler, Schubert and Möllering2012; Müller-Seitz, Reference Müller-Seitz2012; Parry, Reference Parry1998; Uhl-Bien, Reference Uhl-Bien2006) we thus conceptualise interorganisational collaborative leadership for the present study as follows: Interorganisational collaborative leadership is a social process where separate entities come together in order to achieve a common goal and accrue mutual benefit from the relationships, constructed through influential interactions amongst parties, with resultant processes informing coordinating structures for collaboration. This definition recognises that leadership is a process practised by individuals but in the case of interorganisational collaborations, these individuals act as agents and represent the interests of their organisations.

While power is recognised as an important issue in interorganisational collaborative scholarship (see for example Tello-Rozas, Pozzebon, and Mailhot, Reference Tello-Rozas, Pozzebon and Mailhot2015) and social capital is often addressed within the strategic alliances and networks literature, the power that such capitals provide for influence and leadership is largely ignored. Cultural capital is also omitted from discussions of interorganisational collaborations. Bourdieu's capitals provide a means to make power more visible so that it can be explored in greater depth.

The distinction between social and cultural capital is not always clear. Social capital can be defined as ‘features of social organisation, such as trust, norms, and networks, that can improve the efficiency of society by facilitating coordinated action’ (Putnam, Reference Putnam1993: 167). Bourdieu's original definition of cultural capital was based on social mobility, where cultural capital meant being in possession of the capabilities to navigate high-status culture through an individual's disposition, as well as objectified goods such as art and other cultural artefacts, and institutionalised embodied assets such as a degree (Bourdieu, Reference Bourdieu, Szeman and Kaposy1986). This can comprise assets that are in tangible form such as buildings, or intangible assets such as music or language (Throsby, Reference Throsby1999). The concept of cultural capital has expanded, particularly in the area of migration studies, where cultural resources (including ethnicity, country of origin, language, religion, class, values and gender) are forms of cultural capital (Erel, Reference Erel2010; Erel & Ryan, Reference Erel and Ryan2019; Kutor, Raileanu, & Simandan, Reference Kutor, Raileanu and Simandan2021; Smith, Spaaij, & McDonald, Reference Smith, Spaaij and McDonald2019). As the site of enquiry is a multicultural arts festival, we therefore adopt this conceptualisation of cultural capital.

Another significant omission in the literature acknowledged several years ago by Müller-Seitz (Reference Müller-Seitz2012) and not addressed since, is that the predominant research on leadership in interorganisational relationships fails to give appropriate attention to manifested notions of leadership over time. We contribute to this gap through our process model of interorganisational collaborative leadership that accounts for sources of power and the hierarchies of influence that emerge. Power in this sense is presented through Bourdieu (Reference Bourdieu, Szeman and Kaposy1986) capitals and how these capitals shape the collaborative leadership exercise.

Context and background to the research

The collaborative venture under study involved the development of a cultural festival in an Australian city. To preserve anonymity in the research process, we ascribe the pseudonym of ‘Multicultural Arts Festival’ (MAF) to the festival. The programme of MAF entailed collaborations on 280 events across 30 organisations within Australia, over 1000 artists and artistic organisations from 22 nations across the Asia-Pacific region. The shared goals for the festival, and the driving force for adopting a collaborative leadership approach, were to broaden the appetites of traditional arts audiences to include contemporary Asia-Pacific programming, as well as develop a more culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) audience than the traditional attendees of performing arts events in Australia.

During an initial scoping process, the festival curators and all parties initially involved decided that no one individual or organisation had the capacity to build audience diversity across the relevant CALD communities. A collaborative model was thus adopted whereby invited arts organisations in the city would work together as a central body to develop the festival's content and delivery. An additional level of partner organisations would also participate in the festival through programming but would not be involved in the overarching festival development. This model contrasts with the development of other festivals, where contributing organisations traditionally work with festival curators, and with little communication and interaction amongst participating organisations. This presented a unique research opportunity to examine how an intended collaborative form of leadership unfolded in practice.

Given the non-traditional way in which MAF was organised, the group was eager to understand how this model both facilitated and impeded interorganisational collaborative leadership; this was also the motivation for the present study. The aim of this approach was for leadership to not be concentrated in a single organisation but to be a collaborative process whereby leadership could and indeed should be exercised by any one organisation. Our research questions therefore were: (1) How do organisations build interorganisational collaborative leadership as a social process? (2) How do collaborating organisations respond to intentional interorganisational collaborative leadership activities?

Methodology

In order to explain the social process of collaborative leadership and to develop an explanatory model, a longitudinal case study approach using grounded theory analysis techniques was utilised, drawing on the approach of Gioia et al. (Corley & Gioia, Reference Corley and Gioia2011; Gioia, Corley, & Hamilton, Reference Gioia, Corley and Hamilton2012). Theory building from case studies is well documented in qualitative research (Dooley, Reference Dooley2002; Eisenhardt, Reference Eisenhardt1989; Eisenhardt & Graebner, Reference Eisenhardt and Graebner2007; Eisenhardt, Graebner, & Sonenshein, Reference Eisenhardt, Graebner and Sonenshein2016) and allows for a greater understanding of a complex issue within a specific context through the detailed analysis of events and conditions and their relationships within. Importantly, longitudinal case study research supports reflection of the event as it happens, including failures, as well as successes (Dooley, Reference Dooley2002). Access to such a large number of organisations could be considered unusual (Yin, Reference Yin1994), providing an uncommon opportunity to track multiple examples of interorganisational collaboration. While the study sits within the definition of a single case study, a key strength of the study was our unusual research access comprising ongoing opportunities for interviews with collaborating parties.

Data collection and sample

Due to the number of collaborating organisations, we were able to investigate multiple examples of collaborative efforts throughout the months of festival development and delivery, as well as conduct follow-up interviews reflecting on the festival after the event. Data collection took place over a period of 7 months (from January 2017 to August 2017) using semi-structured interviews conducted throughout the development and duration of the festival. Follow-up interviews post festival allowed both real-time and reflective accounts by participants who experienced the phenomenon under investigation and enabled us to take a process perspective.

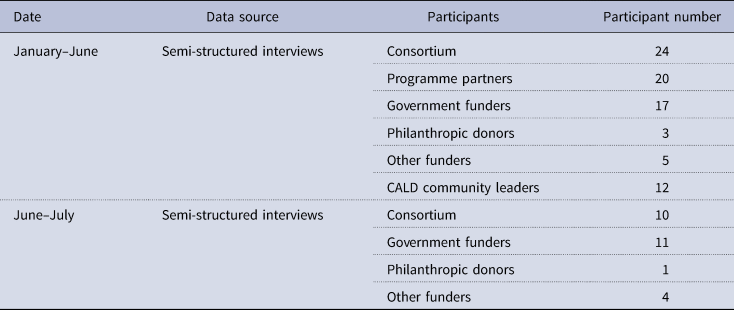

A total of 107 in-depth interviews were conducted via face-to-face or through phone calls across the participating organisations (please see Table 1 for an overview). Eighty-one interviews were conducted before or at the beginning of the festival with 26 conducted afterwards. Sixteen interviews were conducted with ten interviewees from the central organising company (ten interviewees, with five interviewed twice, before and after the festival). Twenty interviews were conducted with 11 consortium members (nine were interviewed twice – before and after the festival - with one organisation declining to participate in the research overall). The interviewees have been ascribed pseudonyms beginning with ‘Con’ in the findings to reflect their consortium status. Further to this, 17 interviews were conducted with 15 programme partners (two programme partners were interviewed twice) with their pseudonyms beginning with ‘Part’. Four philanthropic funders were also interviewed. Thirteen interviews were with individuals who were regarded to be leaders of the CALD communities of which the festival was seeking to involve; their pseudonyms begin with ‘Comm’. Interviewees held either leadership roles within their respective organisations or were recognised within the consortium as having leadership roles across the festival. These additional groups were important, as they were able to reflect on how they experienced the collaborative leadership approach of the consortium from the outside.

Table 1. Data collection

The semi-structured interviews ranged in length from 20 min to 70 min and were conducted primarily face-to-face by the first author and other members of the research team noted in the acknowledgements. An interview guide (see Appendix A) comprised the central themes of the study. We followed the advice of Parry (Reference Parry1998) who argued that using grounded theory to research the process of leadership necessitates initial discussions about leadership-related topics rather than explicitly asking about leadership upfront to avoid the possibility of existing theories or biases being ‘forced’ into the data being gathered (Parry, Reference Parry1998). Follow-up questions involved probing the responses to uncover the presence of relevant themes such as power, influence, collaboration and participation. This approach facilitated the sharing of the participants' views on how collaborative leadership emerged and enacted throughout the development and execution of the festival.

Analysis

Our analysis began with the examination of the first 10 interview transcripts in what Gioia, Corley, and Hamilton (Reference Gioia, Corley and Hamilton2012) describe as first-order analysis or open coding (Glaser & Strauss, Reference Glaser and Strauss1967), which is the selection and categorisation of direct statements drawn from interview transcripts comprise the first round of grounded theory analysis (Corbin & Strauss, Reference Corbin and Strauss2008). At this stage, over 50 categories emerged through constant comparison, a key analysis technique in grounded theory by comparing and contrasting data and emergent categories. First-order categories were named descriptively, reflecting interviewee terms and ideas.

The remaining interviews were coded according to these first-order categories before further analysis, which involved the examination of structures and relationships between the first-order categories. Described by Gioia, Corley, and Hamilton (Reference Gioia, Corley and Hamilton2012) as second-order analysis, these higher levels of abstraction emerged by constantly comparing categories to categories and categories to interview data. This approach has also been adopted by others developing process models to explain collaborative activities (see for example Tello-Rozas, Pozzebon, and Mailhot, Reference Tello-Rozas, Pozzebon and Mailhot2015).

Until this point, we adhered to the grounded theory dictum of avoiding a literature review of the substantive or related areas (Corley & Gioia, Reference Corley and Gioia2011; Gioia, Corley, & Hamilton, Reference Gioia, Corley and Hamilton2012) to prevent the influence of preconceptions (Glaser, Reference Glaser1992). However, with the second-order analysis underway, we reviewed the relevant works of literature (collaborative leadership, interorganisational collaboration, process leadership) for possibilities that we might discover new concepts or whether our findings had precedents (Corley & Gioia, Reference Corley and Gioia2011; Gioia, Corley, & Hamilton, Reference Gioia, Corley and Hamilton2012). The literature was then integrated into the findings through a critical comparison between the extant research and the emergent themes (Glaser, Reference Glaser1998). In line with such approaches, we limit the ‘Findings’ section to reporting of results and analysis. Accordingly, synthesis and evaluation will be contained in the ‘Discussion’ section.

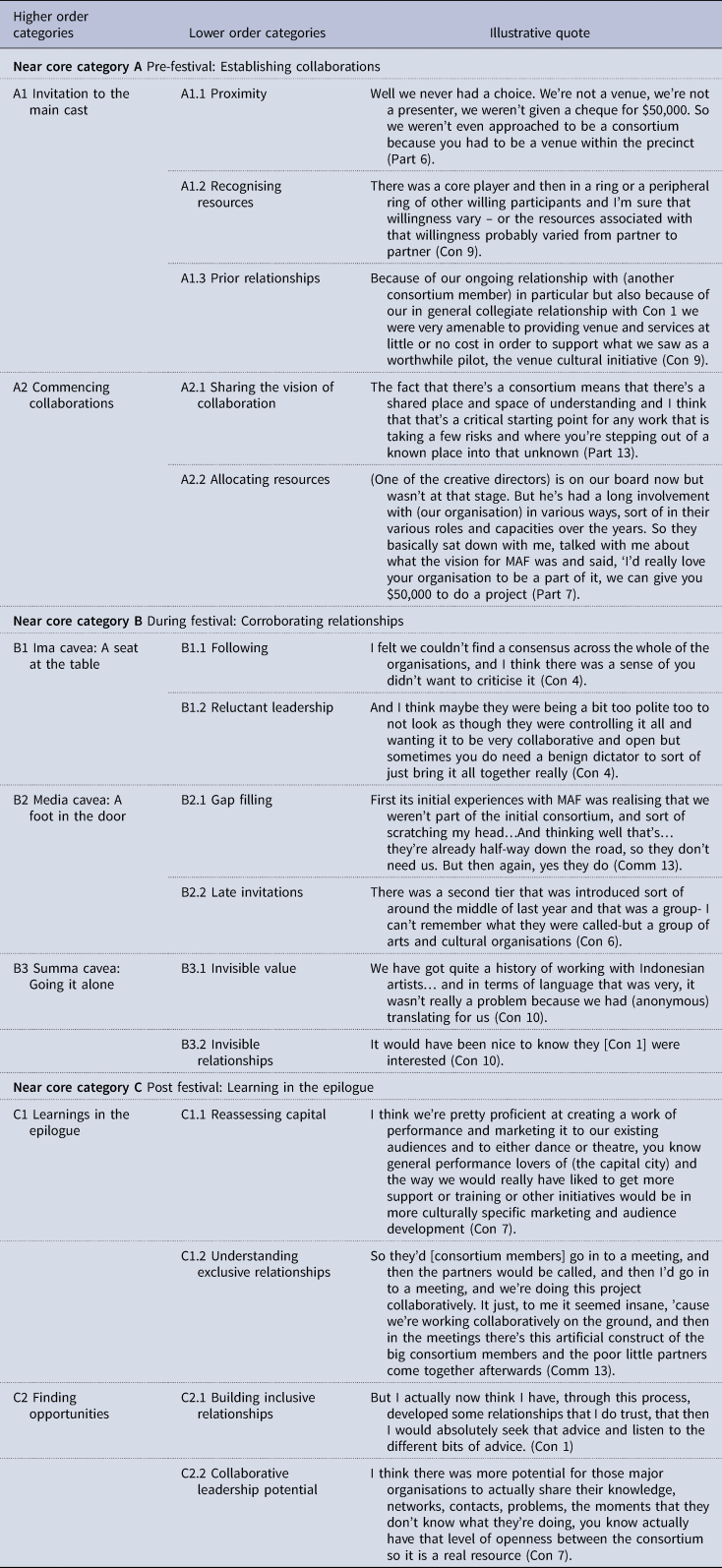

The development of the process model incorporated all the emergent themes outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Leadership by cavea: A process model.

Findings

The overarching model of ‘leadership by cavea’ in Figure 1 describes and explains the social processes occurring as participating organisations attempted to build collaborative leadership over the course of the festival. The three key stages of the festival (before, during and after) are incorporated to explain the social processes occurring throughout. An illustration of this can be found in Table 2.

Table 2. Hierarchical model: Leadership by cavea

Leadership by ‘Cavea’

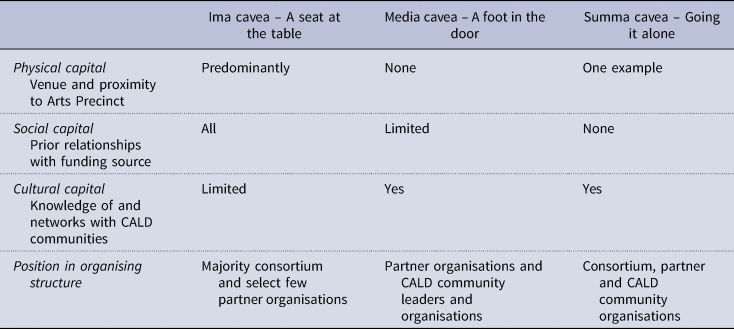

Cavea represents the social hierarchies that emerged and played out through the festival's development and delivery. Cavea is the Latin term for the tiered seating in Ancient Roman theatres. Theatre seating in Ancient Rome was dictated by social rank with the ima cavea representing the highest social class with seating at ground level. The middle class were seated in the middle section media cavea, and the lower classes at the highest level summa cavea. A theatre term naturally lends itself to a model that describes and explains the process of interorganisational collaborative leadership over the course of a performing arts festival. The equivalent social hierarchy of both participation and opportunity for collaborative leadership opportunities presented in this study also reflects three levels of participation as shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Attributes of participating organisations according to cavea tiers

The processes by which the organisations formed the hierarchy for the purposes of the festival and the impact on different organisation's ability to demonstrate their influence during an intended collaborative leadership exercise are now discussed chronologically, as presented in Table 2.

Near core category A: establishing collaborators

‘Establishing collaborators' explains the process of how the initiating organisation sought to build collaborative leadership in the earliest stages of festival planning. The initiating organisation (Con 1) hosted the festival's curators and decided who would be invited as a consortium member or as a partner organisation. This is exemplified in the higher order category ‘invitations for main cast’ (higher order category A1). The criteria used to assess the perceived value of the organisations, and thus merited invitations to be a consortium member, are described in the lower order categories: ‘proximity’ (A1.1), ‘recognising resources’, (A1.2) which were divided into ‘tangible and intangible resources’ and ‘prior relationships’ (A1.3).

Being located in the arts precinct of the city (and as a corollary, proximity to Con 1) was identified as a criterion for consortium membership: ‘It was because we're outside of the CBD, we didn't really fall within the footprint’ (Part 5). The first key resource that was identified was the tangible resource of a venue, seen by those within and outside the consortium as being the key driver for inclusion, with Partner 21 stating, ‘I thought most of the consortium members were venues’. However social capital in the form of a prior relationship with Con 1 was the main criterion that influenced an organisation's status in the festival, something of which participants were aware: ‘So, it's a bit hard to tell how much of that good relationship was also because we all knew each other beforehand’ (Con 5).

The commencement of collaborative relationships (higher order category A2) occurred after Con 1 formally established the structure of the consortium. The influential interactions continued to flow from Con 1 in a manner that we identify as the lower-order categories of ‘sharing the vision’ and ‘allocating resources’.

The shared leadership vision (A2.1) was written in the consortium's guiding principles, and included such statements as:

MAF is a creatively focused, collectively driven project

Capacity building is mutual, flowing in two directions

Consortium projects will be alert to and profile potential connectivity across programs…Develop shared opportunities

Con 1 identified collaboration as important because the festival's programming in Australia was regarded as risky. Despite the perceived risks, it was promise of the spirit of collaboration many consortium members identified as a reason to participate. Six of the 13 member organisations (not including Con 1) stated that a key motivation to participate was to engage in collaborative programming through a consortium model. While there was a spirit of collaboration, the allocation of resources (A2.2) was determined by an informal process and was weighted towards those who had social capital in the form of prior relationships with Con 1: ‘… But they (Con 1) clearly had all of the resources and there was a lot of work being done on the ground on their end that we weren't involved in’ (Con 7).

Near core category B: corroborating relationships

This near-core category explains the emergent leadership patterns occurring as relationships between the collaborating organisations were corroborated. Ima cavea (higher order category B1) represents the organisations (both consortium and partner organisations) that possessed social capital in the form of prior relationships with Con 1 and were beneficiaries of financial capital (i.e., funding and in-kind support) as a result. Within this category, there were two clear perspectives regarding the collaborative experience. In the first, organisations continued ‘following’ (B1.1) Con 1. This was despite Con 1 respondents stating that they attempted to step back from some leadership activities to create a gap for other organisations to step up to lead and generate a more collaborative approach: ‘Where's the presence of the other orgs? I don't know who's responsible for why there's not but it's just not, it's all us’ (Con 1).

Yet the consequence of Con 1 stepping back was that the leadership gap remained unfilled as consortium members continued to follow Con 1 rather than taking up opportunities to lead. This created an environment of ‘reluctant leadership’ (B1.2) as Con 1 wanted other partners to take the lead, particularly in communicating with CALD artists and communities. ‘But I kind of felt as though when that went wrong it was very much our risk to handle rather than workshop’ (Con 1). This shows that Con 1 did not share enough information about how the festival was progressing for other organisations to realise that their leadership was truly needed for the collaborative exercise.

To fill this vacuum, media cavea organisations (higher order category B2) were included in the second wave of invitations. These organisations brought with them an important source of power: the cultural capital necessary for outreach to CALD communities and artists. We therefore identify two lower order categories, ‘gap filling’ (B2.1) and ‘late invitations’ (B2.2). Gap filling describes the consortium's identification of the previously unrecognised intangible resource of cultural capital. ‘You know I kind of went around to all the departments, does anyone speak Korean? Like can you ring the Korean government?…It just flushes out that we don't have those skills, it makes it a degree harder’ (Con 1).

As a result, ima cavea organisations began following media cavea organisations to navigate the cultural minefields. However, the lack of social capital and late invitations meant there was not enough time for their knowledge and expertise to be shared with those who had ‘a seat at the table’. ‘I think we came in really late. From what I understand, everything was quite confirmed for the festival…So that meant that we were very late coming up with a concept’ (Part 8).

The third tier of the collaborative leadership hierarchy is summa cavea (higher order category B3) and represents organisations who were ‘going it alone’. These organisations possessed neither social capital nor were invited to share their cultural knowledge. While they may have had the tangible resource of a venue, they did not receive funding from Con 1; therefore, social capital was elevated above physical capital. We identify two lower-order categories here, ‘invisible value’ (B3.1) and ‘invisible relationships’ (B3.2). The invisible value represents the tangible value of a venue and/or the intangible value of cultural capital, neither of which was recognised or utilised due to a lack of social capital with Con 1. As one partner put it, ‘it's our 21st year this year and then when I spoke to them, they realised that we've actually been doing this for a long time’ (Part 1). This lack of recognition took the form of ‘invisible relationships’ whereby the summa cavea organisations were at the fringes of leadership processes, acting as passive bystanders and left to ‘go it alone’ rather than active leaders or followers. ‘No one came. We had 48,000 people attend and no one from Con 1 came’ (Part 1).

Near core category C: learnings in the epilogue

‘Learnings in the epilogue’ represents the themes that emerged in the interviews that occurred after the festival concluded and illustrate reflexivity towards the leadership process. Higher order category C1 ‘reflecting on the status quo’ captures how respondents identified traditional operating structures of festivals discourage collaborative leadership exercises and encouraged deference to a central organisation at all times. The creation of a consortium was insufficient to generate the extent of collaborative leadership that was originally sought. The lower-order categories of ‘reassessing capital’ (C1.1) and ‘understanding exclusive relationships’ (C1.2) demonstrate the main themes that underpinned the post-festival reflections.

Capital was reassessed, with respondents identifying that the focus on social capital and the approach to resource allocation by Con 1 led to significant power differences and precluded the practice of collaborative leadership that was intended. Consortium respondents also recognised that cultural capital emerged to be a more valuable resource that was originally ignored. ‘But I'm saying, what we were lacking was skill sets, language or otherwise, cultural sensitivity’ (Con 1). This cultural capital should have been integrated into activities throughout the leadership process rather than brought in at a too-late stage. It was also realised that the exclusive relationships with Con 1 prevented this from occurring. Organisations within the media and summa cavea tiers also expressed a concern that once their cultural capital had been utilised, they may be ‘abandoned’: ‘We're panicking now, don't abandon us Con 1’ (Comm 3).

Despite this, there was a positive attitude towards future collaboration; this is expressed in the higher order category C2 ‘finding opportunities’. This category highlights two key areas for improvement in which respondents provided suggestions and proposed solutions to the challenges organisations faced in engaging in collaborative leadership. Through these reflections, two categories emerged: ‘building inclusive relationships’ (C2.1) and ‘collaborative leadership potential’ (C2.2). By the end of the festival, respondents (in particular Con 1) were aware of the importance of looking beyond existing and narrow social ties and the need to build capital (both social and cultural) through inclusive relationships in a deeper and longer-term way. An emphasis on cultural diversity was recognised as a critical way forward particularly for collaborative leadership potential to be realised by ‘(going) out into the community and bring those people in and break those, sort of, barriers down to say you know, this is a space where you can feel welcome, and a place where you can create and do art’ (Con 4). This represents self-awareness about the limitations in the leadership approaches taken.

Discussion

Our first research question asks how organisations build interorganisational collaborative leadership as a social process. From our findings, we have elucidated a social process model of interorganisational collaborative leadership which we also defined at the beginning. This model, as illustrated in Figure 1, sits alongside other process models of collaborative activities (DiVito, van Wijk, & Wakkee, Reference DiVito, van Wijk and Wakkee2021; Tello-Rozas, Pozzebon, & Mailhot, Reference Tello-Rozas, Pozzebon and Mailhot2015) and process leadership (Uhl-Bien, Reference Uhl-Bien2006; Zoller & Fairhurst, Reference Zoller and Fairhurst2007). Ours differs by showing how an intended exercise in collaborative leadership evolved and where social capital proved to be the most significant source of power driving leadership activities. It is important to note that there are two distinct types of social capital. ‘Bridging’ social capital is ‘outward looking and encompass people across diverse social cleavages’ and ‘bonding’ social capital is ‘inward looking (and) tends to reinforce exclusive identities and homogeneous groups’ (Putnam, Reference Putnam2000: 22). That is, relationships in the form of social capital can be used to extend influence or exclusively guard it.

In this study, bonding social capital was held above tangible resources and intangible cultural capital, the latter of which emerged as the most valuable but much later in the process. While research has shown that social capital is often a driving factor behind collaborative relationships (Burt, Reference Burt1992, Reference Burt2000, Reference Burt2004; Ceci, Masciarelli, & Poledrini, Reference Ceci, Masciarelli and Poledrini2020; Dressel, Johansson, Ericsson, & Sandström, Reference Dressel, Johansson, Ericsson and Sandström2020; Dyer & Singh, Reference Dyer and Singh1998; Gulati & Gargiulo, Reference Gulati and Gargiulo1999; Walker, Kogut, & Shan, Reference Walker, Kogut and Shan1997), the role of cultural capital has been largely ignored outside of migration studies. Furthermore, the role social capital plays is extremely relevant for leadership research (Li, Reference Li2013; Swanson, Kim, Lee, Yang, & Lee, Reference Swanson, Kim, Lee, Yang and Lee2020) though its role in the process of collaborative leadership is relatively unexplored.

We demonstrate how physical, social, and cultural capital interact during a collaborative leadership process to create a structure of relationships between organisations according to a tiered system of caveas. Each cavea represents different levels of power and inclusion, providing those in the more privileged tiers greater access to resources and opportunities to influence. As pointed out by Lamont and Lareau (Reference Lamont and Lareau1988), Bourdieu's view of capital is that they are tools of power for ‘exclusion and symbolic imposition’, which we have addressed through our framework. This deeper understanding of different forms of power as antecedents to influence within interorganisational collaborative leadership is a noted omission in the literature (Denis, Langley, & Sergi, Reference Denis, Langley and Sergi2012) and is one of the key contributions of our research. While it has been argued that borrowing capital leads to the creation of hierarchies (Burt, Reference Burt2000) our framework delineates those hierarchies and explains the underlying sources of power and how they are formed and enacted in the process of a collaborative leadership exercise. This is contrasted with the work of Zhang and Guler (Reference Zhang and Guler2020) who have identified the role power plays in creating hierarchies in collaborative relationships but does not map out the temporal nature of these relationships and how leadership emerges at various stages.

Hierarchies during collaborative leadership exercises are not necessarily a problem given that when a central organisation acts as a hub-firm, hierarchical relationships are extremely common (Müller-Seitz & Sydow, Reference Sydow, Windeler, Schubert and Möllering2012). Similarly, organisations in collaborative relationships often rely more on social capital and existing relationships rather than pursuing new relationships (Ceci, Masciarelli, & Poledrini, Reference Ceci, Masciarelli and Poledrini2020; Dressel et al., Reference Dressel, Johansson, Ericsson and Sandström2020; Dyer & Singh, Reference Dyer and Singh1998; Gulati & Gargiulo, Reference Gulati and Gargiulo1999; Walker, Kogut, & Shan, Reference Walker, Kogut and Shan1997). Our research shows how an over-reliance on social capital creates hierarchies within a leadership process and how these hierarchies can inhibit freer flows of power and influence, which would engender greater collaborative leadership activities. These hierarchies create lost opportunities to share knowledge for the purpose of building capacity, a key tenet of any collaborative exercise (Hao, Feng, & Ye, Reference Hao, Feng and Ye2017; Le Pennec & Raufflet, Reference Le Pennec and Raufflet2018; Müller-Seitz, Reference Müller-Seitz2012; Zhang & Guler, Reference Zhang and Guler2020). It can also create missed opportunities for individuals and the organisations they represent to take on leadership roles and participate more fully in a collaborative leadership process.

Our second research question aims to understand how organisations respond to intentional interorganisational collaborative leadership. A key finding is that when there are clear power disparities amongst the group, if a leading organisation attempts to step back to allow others to exert greater influence, the leadership vacuum is not likely to be filled when a leading organisation holds such concentration of power. This could have been avoided if Con 1 understood the ‘power of their position’ (Huxham & Vangen, Reference Huxham and Vangen2000) and that it was necessary to recognise and reduce the power differences within groups and across hierarchies.

With Con 1 dictating activities from the beginning, bonding social capital was the most powerful resource with which to exert influence. This meant that organisations that held the important cultural capital were unable to take up important leadership opportunities when they were critically necessary. Participants eventually realised that to unlock this important cultural capital in the future, social capital needs to be built across all three tiers in the cavea hierarchy. For this to have occurred, one can argue that the organisation with the most power in the collaborative exercise should exhibit leadership initially by actively seeking out new partners (as well as encouraging others in the core group to do the same). Then they should cede power by explicitly inviting others to take on leadership roles rather than assuming it would happen organically.

We instead saw a collaborative network needing to borrow cultural capital later in the leadership process, something not previously addressed by researchers on collaborative leadership. Burt (Reference Burt2000) cautions against borrowing social capital rather than developing and integrating relationships across a network; that is, using someone's capital for a brief transactional period but not providing commensurate benefit in return. Our research shows that borrowing cultural capital can also lead to hierarchies and lower likelihoods of collaborative leadership success.

By uncovering power relations, namely the various capitals that drove the hierarchy of relationships, we believe we have added to a deeper sense of what interorganisational collaborative leadership looks like in practice and provided a more fluid interpretation of how groups and organisations step in and out of these roles and relationships. What we demonstrate in our model is a natural structuration of relationships into a hierarchy as part of an interorganisational collaborative leadership process that was driven by the power sources of physical capital, bonding social capital, and borrowing cultural capital. If Con 1 and other consortium organisations had truly recognised and valued the social and cultural capital that was necessary for the festival to succeed, then the cavea hierarchies may not have been as exclusionary. Or indeed, these hierarchies may not have emerged at all, with flatter structures and decentralised power allowing for more fluid collaborative leadership. Thus, for collaborative leadership to be a more inclusive process and for resources and risks to be truly shared, organisations must be aware of slipping into tiered hierarchies due to an overreliance on bonding social capital and miss out on opportunities to achieve their shared goals.

The model we present is descriptive, not prescriptive. It demonstrates the complex and often messy process of leadership when organisations come together to address large-scale problems that transcend one institution. The model can be used as a conceptual lens through which such processes can be viewed and explored, recognising the critical interplay of various forms of capital, how they inform the structuring of collaborative relationships and highlighting areas of leadership success as well as key gaps in the process.

Conclusions, limitations and implications

Our aim in this study was to heed the call to go deeper into power dynamics within leadership (Dhanaraj & Parkhe, Reference Dhanaraj and Parkhe2006; Ladkin & Probert, Reference Ladkin and Probert2021; Tsai, Reference Tsai2001) and towards seeing multiple performative perspectives on what constitutes ‘collaborative leadership’ across organisations. Our findings depart from Huxham and Vangen (Reference Huxham and Vangen2000) somewhat as we identify the importance of power in the form of intangible resources, namely social and cultural capital, for not only building the foundation of the collaborative leadership exercise but also explaining the various responses. We therefore add to their theoretical understanding of interorganisational collaborative leadership by expanding on the nature of power and its role in structuring hierarchical relationships.

We suggest that whilst there may be orchestration (Dhanaraj & Parkhe, Reference Dhanaraj and Parkhe2006) there are also other metaphoric leadership frames to which we can make sense of leadership in collaboration. In this grounded theory approach, we have found three tiers of engagement that we represent as ima cavea, media cavea and summa cavea to illustrate the structure of the interorganisational collaborative leadership process, as demonstrated in Figure 1. By doing so we have uncovered previously hidden hierarchical power structures (Empson, Reference Empson2020) within the collaborative leadership perspective (Chrislip, Reference Chrislip2002; Chrislip & Larson, Reference Chrislip and Larson1994; Crosby & Bryson, Reference Crosby and Bryson2005, Reference Crosby and Bryson2010; Huxham & Vangen, Reference Huxham and Vangen2000; Kramer & Crespy, Reference Kramer and Crespy2011; Kramer et al., Reference Kramer, Day, Nguyen, Hoelscher and Cooper2019; Müller-Seitz & Sydow, Reference Sydow, Windeler, Schubert and Möllering2012; Sydow et al., Reference Sydow, Lerch, Huxham and Hibbert2011). We contribute further through taking a deeper process perspective (Hosking, Reference Hosking1988; Knights & Willmott, Reference Knights and Willmott1992; Parry, Reference Parry1998; Sutherland, Land, & Böhm, Reference Sutherland, Land and Böhm2014; Wood, Reference Wood2005) demonstrating that over time, the structure of the relationships and the power inherent in the resources shifts. This extends the work of others who have examined interorganisational collaborations (Huxham & Hibbert, Reference Huxham and Hibbert2008; Tello-Rozas, Pozzebon, & Mailhot, Reference Tello-Rozas, Pozzebon and Mailhot2015; Zhang & Guler, Reference Zhang and Guler2020) by demonstrating how power, particularly social capital, is wielded as a form of influence in name of collaborative leadership, often in unintended and sometimes disadvantageous ways. Our findings also beg the questions ‘how might this exercise have differed if the organizing had started from the bottom up rather than top-down fashion?’ and ‘what if the consortium had started with the partner organizations?’ We strongly encourage other researchers to take up opportunities to study interorganisational collaborative leadership in circumstances where influence emerges from organisations and sources that are not in such obvious positions of power.

In practice, organisations must be aware of how power imbalances in relationships can subvert collaborative activities and create more traditional and hierarchical structures, what Huxham and Vangen (Reference Huxham and Vangen2000) refer to as ‘power in the position’. Clear processes and guidelines for interorganisational collaborative leadership activities must be stipulated from the outset, such as rotating leadership activities and empowering those with less status and resources to join the table, in order to encourage other organisational actors to transform their power into influence and practice leadership.

A thorough understanding of the resources necessary to achieve the collaborative goals is essential, recognising that due to exclusionary power structures, valuable capital may be held by those who have been prevented from participating and sharing. Deken et al. (Reference Deken, Berends, Gemser and Lauche2018) caution against exploiting social capital to the extent that it risks future collaborations. Rather than ‘burning’ and ‘borrowing’ social capital, we advise going beyond existing networks and seeking collaborators with other important forms of capital, in this case, cultural capital, taking a ‘bridging’ and ‘building’ approach. Finally, we advocate for collaborative leadership as an on-going reflective practice. In our study, participating organisations came to realise their missteps and oversights that prevented them from achieving their collaborative leadership ideals by engaging in reflexive evaluation. The practical implication is for organisations to embed reflection and evaluation within all interorganisational collaborative relationships.

There are a number of opportunities for future research. Within our study, we also found important reflections on how an arts collaboration seemingly had an interesting colonial/postcolonial tension in cultural terms. The reflections of CALD leaders pointed to such tensions and while outside of the scope of this paper, their recognition of their exclusion within sector dominated by Western people and values, merits further attention. We would therefore recommend that collaborative ventures should also be explored with a critical cultural lens imbibed within any analytical interpretation.

This is one of the limitations of the present study. We also recognise that the site of research, an Australian-based multicultural arts festival, is not easily replicable and the nature of the event and the organisations participating means that there are likely particularities about our findings that may not be found elsewhere. That we chose an event with clear timelines also means that our model may not fit as neatly for the study of leadership in on-going interorganisational collaborations. For example, ‘learnings in the epilogue’ may be found within the leadership process with reflexivity occurring on a consistent basis rather than at the end of the intended collaborative leadership exercise. However, it can be translated to project activities within ongoing collaborative relationships and in responses to significant crises that require the mobilisation of many organisations. We strongly encourage others to take up the mantle of investigating such relationships to uncover more about the complex and challenging phenomena that is interorganisational collaborative leadership.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contributions of those involved in data collection: Hilary Glow, Katya Johanson, Anne Kershaw, Amanda Coles, and Jordan Vincent. We would also like to thank Jeff Shao for providing feedback on an earlier version of this paper and Karryna Madison for research assistance. Funding for this research was provided by the City of Melbourne and the Australian government through the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and the Department of Communications and the Arts.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare none.

Appendix A: Indicative interview questions

• How did the idea of the festival come to be?

• What was the process of developing the consortium approach?

• How did your organisation come to be involved?

• What made your organisation want to be involved?

• Could you describe the decision-making processes you engaged in?

• How was leadership practised in the development and delivery of the festival?

• With whom did you partner as part of development and delivery

• Did you feel this style of collaboration was effective?

• Would you work in this way again? Why/why not?