During the first half of the twentieth century, laws mandating segregation of Black and white citizens proved so durable throughout the U.S. South because they were upheld by a bipartisan consensus in Washington, D.C. The Republican Party's interest in pursuing legal reforms that would have challenged Jim Crow at the state-level had mostly waned by the 1890s. Democrats, now firmly entrenched at the state and federal levels, were wholly wedded to white supremacy.Footnote 1 Black citizens organized and advocated for their rights, but mostly found themselves without allies in Congress or the White House.Footnote 2 This pattern held until the presidency of Franklin Delano Roosevelt when, thanks to bold political organizing and the nation-wide mobilization for World War II, elected officials faced renewed pressure to address the profound injustices faced by African-Americans.Footnote 3 Reflecting the changed political environment created by the war, Congress passed new civil rights laws in 1957 and 1960—the first enacted since 1875. In 1962, Congress passed the 24th amendment banning the poll tax. Three years later, the Civil Rights Act (CRA) and Voting Rights Act were on the books.

The landmark legal enactments central to America's “Second Reconstruction” could not have passed absent the emergence of a bipartisan, interregional coalition of lawmakers who were willing to upend the white supremacist political order.Footnote 4 With southern Democrats voting as a bloc against any legislation that challenged Jim Crow's institutional supports, northern Democrats championing new legal protections for Black citizens could only succeed by winning support from conservative Republicans who represented constituencies across the northern and western portions of the country. The pro-civil rights coalition that emerged in the first half of the 1960s included liberals such as Rep. Emmanuel Celler (D-NY) and Senator Hubert Humphrey (D-MN), as well as conservatives such as Rep. Charles McCulloch (R-OH) and Senator Everett Dirksen (R-IL). The cooperative efforts of lawmakers with very different ideological perspectives helped overcome the southern filibuster in the Senate, the central obstacle faced by those seeking new civil rights laws.

By 1965, tensions internal to the congressional civil rights coalition prevented additional legislative successes. America's Second Reconstruction had, by this point, begun to lose steam.Footnote 5 In 1966, President Lyndon Johnson proposed a new civil rights bill which, among other things, would have banned discrimination in the sale or rental of houses across the United States. Lawmakers—both Democrat and Republican—representing voters beyond the Southeast responded with deep opposition. Johnson's supporters in the House muscled it through, only to see it killed by a filibuster in the Senate. Two years later, Congress did pass a new civil rights law aiming to address housing discrimination, but only because its authors wrote the bill so that white sellers could continue to legally discriminate against Black home buyers.Footnote 6 Such compromises, argued Roy Wilkins, executive director of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), ensured that “that the suburbs would remain virtually Lily-White and the center city ghettos would become poorer, blacker, and more desperate than at present.”Footnote 7 Modern accounts of housing segregation bear out Wilkins’ prediction.Footnote 8

To those who believed that features of the oppressive Jim Crow regime remained in place as long as American suburbs remained segregated, Richard Nixon's victory in 1968 was a worrisome signal. Domestic political momentum was shifting toward those who were skeptical of further legal challenges to institutionalized white supremacy which had the potential to impact life outside of the South: for example, in the buying and selling of homes or in the composition of northern schools. Residential segregation and its primary consequence—de facto segregation of elementary and secondary schooling—were two modes of structural racism that proved immune to legal reform because rooting them out would have required new law with nationwide reach. To fully desegregate American schools would mean taking on residential segregation in northern towns and cities where many saw it as informal and, some claimed, “almost ‘natural.’”Footnote 9

Defending modes of racial segregation that were harder to attribute to formal legal enactments was a new coalition of legislators who advocated for a “color-blind defense of the consumer rights and residential privileges of middle-class white families.”Footnote 10 By the late 1960s, massive resistance and explicit racism were less politically palatable, a shift that historian Matthew Lassiter attributes to the declining political power of the rural South. Instead, the growing population of suburbanites in the South began to see their preferences enacted into policy. And suburban voters, North and South, were uncomfortable with de jure segregation and explicit forms of racial animus. They were converging instead on a defense of the “structural mechanisms of exclusion” that did not “require individual racism … in order to sustain white class privilege and maintain barriers of disadvantage facing urban minority communities.”Footnote 11 Segregated schools and the segregated neighborhoods that surrounded them were two of the most durable components of this “structural exclusion.”

We examine the protracted legislative battle in Congress over school busing, a policy aiming to facilitate integration through the transportation of children to schools outside their immediate neighborhoods. Decades of residential segregation ensured that even where segregated schooling was not required by law—as it was through the South—many children attended schools that were “de facto” segregated. Segregated neighborhoods meant segregated schools. The only way to avoid this outcome was to send children to different schools “across town.” The controversies that grew out of busing politics have been examined by scholars of law and American politics. They have produced excellent, regionally specific analyses highlighting local conflicts between supporters and opponents of this policy.Footnote 12 Some have also written about the legal history and implications of court intervention on this issue.Footnote 13 Yet Congress’ role in setting policy that impacted busing programs in the states has gone largely unexamined.

We add to the scholarship that already exists by analyzing busing policy from the congressional perspective. Doing so allows us to illustrate the power of the legislative coalition espousing what is now known as “color-blind conservatism.”Footnote 14 Color-blind conservatism, according to Lassiter, captures the politics of “white, middle-class identity” which defines “freedom of choice” and “neighborhood schools” as the “core privileges of homeowner rights and consumer liberties that rejected as ‘reverse discrimination’ any policy designed to provide collective integration remedies for past and present policies that reinforced systematic inequality of opportunity.”Footnote 15 Color-blind conservatives, both North and South, rejected congressional attempts to bring the federal government in on the side of state-level busing programs. When the Supreme Court began mandating school desegregation through busing and actors in the administrative state tried to force compliance, these antibusing lawmakers responded by withholding any aid that would have made it easier for school districts to obey. In what follows, we show what happens when the Supreme Court and the administrative state set out to create policy that is opposed, vehemently, by lawmakers in the legislative branch. When it came to busing policy, members of Congress did not fall in line. They struck back with legislation that defied the Court and the bureaucracy.

Important analyses of the 1964 CRA explain how “weaknesses” built into the bill were turned into “strong policies” anyway, thanks to efforts by the courts and political action outside of Congress.Footnote 16 We show that in the case of busing, the weak state produced weak policy. The CRA did end “de jure” segregation, but this legal pronouncement did not produce integrated schools in the South, nor did it tackle the problem of “de facto” segregation in the North and West. Instead, it shifted important policy-making decisions related to school integration onto the administrative state and the court. Once judges and bureaucrats began working to integrate the nation's schools, political support from the elected branches of government largely collapsed. By this time, the more local, “grass-roots rebellion against liberalism” identified by Thomas J. Sugrue had made its way to Washington, D.C.Footnote 17 With few tools at their disposal to act on favorable court decisions, and motivated opposition from those who did not want to bring the federal government in on the side of local busing programs, liberal lawmakers, supportive judges, and committed bureaucrats could not overcome the opposition mounted by the color-blind coalition.

By focusing on Congress’ role in busing politics, we shed light on the failure of the federal government to reverse decades of segregated schooling nation-wide. We explain this failure by documenting the breakdown of the coalition responsible for passing landmark civil rights laws, and its replacement by an interregional coalition of lawmakers who worked together to stymie any federal efforts to advance the cause of Black civil rights. From 1966 until the early 1990s, lawmakers operating from this perspective would determine the boundaries of new civil rights proposals.

We proceed in the following way. The “The Politics of Desegregation: 1954–66” section briefly recounts the ruling in the “Segregation Cases” of the early 1950s and then explains how Congress sought to implement them in the CRA of 1964. Here we focus on the ways in which congressional legal enactments set the stage for conflict over the enforcement of provisions related to school integration. The “The Politics of Busing: 1966–86” section explains how this conflict over enforcement led to a prolonged congressional debate over busing, specifically. Here we pay particular attention to floor debates and roll-call votes on busing policy. In so doing, we document the emergence and political significance of the bipartisan, anti-civil rights coalition.

The Politics of Desegregation: 1954–66

Writing for the majority in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), Chief Justice Earl Warren declared that “in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”Footnote 18 Warren's assertion explains why the court declared unconstitutional those laws mandating segregated schooling. Up to that point, “separate but equal” facilities of all kinds were understood to be wholly constitutional. Congress explicitly endorsed the principle in the early 1880s, during the first (failed) effort to appropriate federal funds to American primary and secondary schools.Footnote 19 Nearly two decades later, the Supreme Court provided its stamp of approval in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). For more than seven decades, a legal regime built to guarantee racially separate and radically unequal school facilities was implemented across the Southeast. Now the Court judged segregation under the sanction of law (de jure segregation) to be harmful to the social and psychological development of those children forced into all-Black schools. Segregated schools therefore violated the “equal protection of laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.” Laws compelling segregation in twenty-one states were immediately invalidated.Footnote 20

Brown is credited with helping to finally bring an end to Jim Crow, and legislative efforts to implement its decision-motivated congressional debate for more than two decades after the decision was handed down. It is important, therefore, to be clear about what the court said. In Brown, the court disqualified only de jure segregation: segregation compelled by the law. This point was further clarified in the companion case to Brown, Bolling v. Sharpe (1954). Here the court decided that “compulsory racial segregation in the public schools of the District of Columbia” violated the constitutional rights of Black children.Footnote 21 In neither Brown nor Bolling did the court challenge the constitutionality of de facto segregation: “racial imbalance which results when otherwise fair school districting is superimposed upon privately segregated housing patterns.”Footnote 22

The distinction between de jure and de facto segregation would come to play a central role in congressional debates over how to legislate an end to the system of separate schools. As we will explain later, the bipartisan but primarily northern coalition responsible for enacting the 1964 CRA took seriously this distinction because they saw segregation patterns outside the South as de facto, not de jure. Many northern lawmakers thus believed their communities to be exempt from Brown and relevant provisions of the 1964 CRA.

The court also said nothing in Brown about how schools would be desegregated or how their efforts to desegregate would be verified. At first, the court delayed any discussion of implementation because of the “considerable complexity” involved. In Brown II (1955), the Court stipulated that,

full implementation … may require solution of varied local school problems. School authorities have the primary responsibility for elucidating, assessing, and solving these problems; courts will have to consider whether the action of school authorities constitutes good faith implementation of the governing constitutional principles.Footnote 23

Neither decision set out a plan to guide local school administrators or criteria for determining what counted as “good faith implementation.” These were judgments that would be considered on a case-by-case basis. States subject to the Court's ruling responded by doing very little to heed Brown. By 1964, only 1.2% of Black children in the South attended a public school that also enrolled white students.Footnote 24

Congress provided no guidance either. Lawmakers passed two new civil rights laws shortly after Brown: one in 1957 and another in 1960. Neither challenged the persistence of legal segregation throughout the South, or worked to implement Brown. In 1963, due in part to the violent white reaction to civil rights protests, the Ku Klux Klan's bombing of a Black church in Birmingham, and the assassination of Medgar Evers, Congress finally began to mobilize. Reps. Emmanuel Celler (R-NY)—Chairman of the House Judiciary Committee—and William McCulloch (R-OH)—the Committee's Ranking Member—agreed to cooperate on a new civil rights law. Leveraging Subcommittee Number 5 as a vehicle for crafting a new bill, Celler and McCulloch convened more than 3 weeks of public hearings exploring what the law should cover.Footnote 25 The bill they eventually crafted—H.R. 7152—guaranteed new voting rights protections, prohibited segregation in “public accommodations,” and created a new Equal Employment Opportunities Commission.Footnote 26 Two specific provisions of their proposal addressed the country's school system: Title IV outlawed legal segregation in public schools and Title VI allowed federal agencies to cut off financial aid to any school systems refusing to integrate. Conflict over what these provisions required, and how they would be implemented, proved central to the busing debates that began soon after the 1964 CRA was enacted.

School desegregation: Title IV

Although H.R. 7152 was still being designed, Reps. Celler and McCulloch made a decision that proved highly consequential to the coming debate over busing. Deferring to the preferences of northern lawmakers, they crafted the bill to address only de jure school segregation in the South and not seek to reverse “racial imbalances” in northern schools even though they were also highly segregated. Indeed, in February 1958, The Crisis published a report by the Chicago branch of the NAACP estimating that “91 percent of the Chicago elementary schools were de facto segregated in the spring semester of 1957.”Footnote 27 By 1960, the NAACP had filed lawsuits against the school systems in different northern cities alleging unconstitutional forms of segregation.Footnote 28 Approximately one year after Congress passed the CRA, more than a dozen northern communities filed similar complaints with the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW).Footnote 29 These complaints were mostly ignored because, as both judges and legislators argued, segregation in the North was not compelled by law. Residential segregation was treated as just one consequence of “customary” housing choices made by free citizens. Because it followed from the private behavior of real estate agents, buyers, and purchasers, rather than the state, it could not be reversed by law. The schools serving children who lived in neighborhoods that were segregated in this ostensibly informal way were also, therefore, divided by race.

Approximately one year after Brown, the NAACP filed a lawsuit challenging de facto segregation. In Bell v. School City of Gary Indiana (1963), the Seventh District Court of Appeals ruled that the de facto segregation present in Gary did not violate the constitutional rights of Black children. Those enrolled at the schools they attended were judged by the court to reflect housing patterns for which there was no constitutional remedy.Footnote 30 When the Supreme Court chose not to review the decision issued in the Gary case, members of Congress understood the Court to be saying that segregation of this kind did not violate the Constitution. From the perspective of Reps. McCulloch and Celler, law and politics aligned on this point. When H.R. 7152 moved over to the Senate, it was endorsed by Everett Dirksen (R-IL) in part because he was “convinced that it would not apply in the North.”Footnote 31 As Charles and Barbara Whalen point out, the decision to stipulate that segregation in northern cities was exempt from the law represented an “end-justifying-the-means concession to northern members of Congress.”Footnote 32 The House passed the initial version of H.R. 7152 on February 10, 1964, by an overwhelming vote of 290-130.Footnote 33

In the Senate, H.R. 7152 was also managed by one Democrat and one Republican: Hubert Humphrey (D-MN) and Thomas Kuchel (R-CA). Similar to their House counterparts, Humphrey and Kuchel made clear that this bill would not challenge de facto segregation. In his comments introducing H.R. 7152, Kuchel explained that its opponents “erroneously implied that Title IV would provide funds to secure racial balance in all school throughout America.” Not so, he countered. “The House specifically … provided that ‘desegregation’ shall not mean the assignment of students in public schools in order to overcome racial imbalance.”Footnote 34 In response to a question from Robert Byrd (D-WV) about the busing of students, Humphrey argued,

while the Constitution prohibits segregation, it does not require integration. The busing of children to achieve racial balance would be an act to affect the integration of schools. In fact, if the bill were to compel it, it would be a violation, because it would be handling the matter on the basis of race and we would be transporting children because of race. The bill does not attempt to integrate the schools, but it does attempt to eliminate segregation in the school systems.Footnote 35

The bill's chief spokesmen in the Senate were now on the record stipulating that H.R. 7152 would only prohibit laws that explicitly and intentionally blocked integrated schooling.Footnote 36

Statements from the bill's bipartisan cosponsors were unable to put at ease those who feared “forced integration.” Rather than simply voting on the version of H.R. 7152 passed by the House, the Senate took additional steps to calm the nerves of those lawmakers who feared that the bill might apply to northern communities. An amended version of the bill, referred to as the “Mansfield–Dirksen Substitute,” included the following language in Title IV:

[N]othing herein shall empower any official or court of the United States to issue any order seeking to achieve a racial balance in any school by requiring transportation of pupils or students from one school to another or one school district to another in order to achieve such racial balance.Footnote 37

Senator Jacob Javits (R-NY), an outspoken supporter of H.R. 7152, insisted that this new language merely reaffirmed that the bill would not apply to “cases where there is a racial imbalance in a school even though there is no constitutional denial of admission to that or any other school on racial grounds.”Footnote 38 Going further, Javits added into the Congressional Record an analysis of the bill produced by HEW in which those who would be responsible for administering the law stipulated that “De facto school segregation brought about by residential patterns and bona fide zoning on the neighborhood school principle does not violate the constitutional rights of Negro students.”Footnote 39

Southern members were clear that, as they saw it, H.R. 7152 was written to exempt northern cities from Title IV. Just prior to the Senate vote to invoke cloture on H.R. 7152, Richard Russell (D-GA) proclaimed his belief that “the bill has been drafted in such a way that its greatest impact will be on states of the old Confederacy.” He then warned: “But make no mistake about it, if this bill is enacted into law, next year we will be confronted with new demands for … further legislation … such as laws requiring open housing and the ‘busing’ of students.”Footnote 40 Strom Thurmond (R-SC) offered a similar critique, claiming that H.R. 7152 contained “safeguards” that kept it from challenging the “de facto type of segregation practiced in northern cities.” Thurmond also warned that after enactment, “voices from other parts of the country will make themselves heard about the dangers from the backlash … and delayed fallout, which is bound to occur outside the southern target area.”Footnote 41 These were accurate predictions.

In 1964, at the height of the Second Civil Rights Era, northern members of Congress worried about challenging segregation in their own communities. To declare that “racially imbalanced” public schools were unconstitutional would amount to an attack on “neighborhood schools” that were divided by race even in the absence of laws mandating separation.Footnote 42 Recognizing the unwillingness of their northern colleagues to challenge de facto segregation, southern members correctly assessed that any discussion of mandated integration in the North would engender a backlash against the broader civil rights agenda. They also previewed a strategy that they would adopt when it came time to implement the 1964 CRA: remove formal prohibitions on the enrollment of Black children in previously white schools and then claim that all remaining segregation was de facto. Challenging this approach would generate deep opposition from northern white “moderates” when busing legislation was the subject at hand.

School desegregation: Title VI

Title VI of the 1964 CRA empowered federal agencies “administering a financial assistance program” to withhold money from school districts that refused to stop discriminating against Black children.Footnote 43 This provision of the law directed agencies overseeing the distribution of federal aid to develop and publicize a “rule, regulation, or order of general applicability” that would serve to guide desegregation efforts throughout the South. This rule would communicate to aid recipients how they were supposed to implement desegregation orders, and how their efforts would be evaluated. Rather than mandating congressional approval of the rule, Title VI also made clear that it would go into effect after being approved by the president.Footnote 44 Once approved, the Attorney General was authorized to sue individual school districts on behalf of Black children who were forced to attend schools deemed to be legally segregated. Although this provision did not only apply to schools, aid cutoffs to enforce Brown came up repeatedly during the debate.

Title VI of the CRA was written to end all federal support for institutions still enforcing “separate but equal” rules. Here again, however, Congress inserted loopholes that would prove self-defeating to the bill's stated aims. By making agencies responsible for defining and measuring segregation, Congress chose not to set out a clear standard for deciding when a school district was discriminating in ways that violated the law. Senator Albert Gore (D-TN) used this feature of the bill as one justification for his opposition to the CRA. “An analysis of language [of the bill],” he explained, “reveals … that there is no definition of the word ‘discrimination’. What is ‘discrimination’ … as used in the bill? There is no definition of that word anywhere.” Without a clearly articulated standard, Gore asserted, Congress would be “leaving to those who administer Title VI the authority to prescribe the acts that would be prohibited.”Footnote 45 Gore's assessment was correct. Congress had delegated the authority to determine the meaning of “discrimination” and “segregation” to HEW's Office of Education.

Those working in the Office of Education when the 1964 CRA was passed did not, however, have a “clear idea of the standards to be used in evaluating the desegregation plans school districts would submit to remain eligible for federal funds.”Footnote 46 HEW's General Counsel was himself worried about Congress’ decision to delegate on this subject, telling Gary Orfield that legislators were forcing “the department into extremely sensitive areas of regulation.”Footnote 47 By saying nothing, Congress forced unelected bureaucrats working in the Office of Education to either improvise their own standard or rely on one crated by unelected judges.Footnote 48 What “desegregation” meant in practice shifted multiple times throughout the latter half of the 1960s.

The first guidance provided by HEW in 1964 explained that school districts would be meeting their obligations if they implemented so-called “freedom of choice plans.” This meant that as long as Black children were offered a “fair” opportunity to enroll in what had previously been an all-white school, that district could be said to have desegregated.Footnote 49 In a 1965 article published in the Saturday Review, for example, G.W. Foster—an administrator in the Office of Education—explained that “freedom of choice is unobjectionable” as long as “administrative practices within the school system make” do not “make the exercise of choice a burden.” Foster also concedes that “it is difficult to advise with certainty concerning the rate at which desegregation must be completed.”Footnote 50 A year after the CRA was enacted, in other words, administrators responsible for implementing it still had not developed a clear standard for determining how to judge the pace or quality of desegregation.

“Freedom of choice” plans, submitted to HEW for approval by local school districts, soon became the basis for “one-way integration of individual black students into white schools.” White citizens both North and South believed that integration carried out this way was “race neutral” because the policy allowed Black children to attend white schools. As Lassiter explains though, freedom of choice largely preserved the racial composition of “neighborhood schools” which were themselves a reflection of residential segregation.Footnote 51 Once HEW had sanctioned “freedom of choice” as an acceptable way to meet the requirements of the CRA, potential opponents of school integration fell into line. According to Orfield, “citizens and the political leadership in the South” came to believe that “freedom of choice was all that the Civil Rights Act required.”Footnote 52

By 1966, however, HEW came to doubt the efficacy of freedom of choice plans. Administrators revised the guidelines to say that allowing Black children the option to enroll in a white school was not itself sufficient to demonstrate good faith implementation of the 1964 CRA. Instead, HEW would assess individual school districts based on whether the plan adopted by local officials was contributing to the “orderly achievement of desegregation.” “The single most substantial indication as to whether a free choice plan is actually working to eliminate the dual school structure,” the new guidelines explained, “is the extent to which Negro or other minority group students have in fact transferred from segregated schools.”Footnote 53 HEW's more stringent guidelines were subsequently endorsed by the Supreme Court in Green v. County School Board of New Kent County (1968), when the Court held that desegregation by freedom of choice plans was not a valid means for ending the dual school system. Once the courts and HEW made clear that compliance with the 1964 CRA required demonstrable progress toward school integration, busing became the only option. For only by busing students could lawmakers integrate schools while leaving untouched the segregation that characterized so many of the fastest growing areas of the country.

The Politics of Busing: 1966–86

Busing fights during the Johnson era

The congressional fight over federal busing policy began in earnest in the spring of 1966. On May 9, during consideration of a new CRA, Senator Sam Ervin (D-NC) took the floor to complain that “important Health, Education, and Welfare programs are being placed in jeopardy by an effort on the part of certain federal officials to correct so-called racial imbalance in the states.” According to Ervin, officials within HEW's Office of Education—those responsible for developing and implementing desegregation policy—were acting contrary to the “language … [and] legislative history of Title VI [of the 1964 CRA].” Citing Hubert Humphrey's statement in 1964 disclaiming any intent on the part of those supporting the CRA to pursue full integration of the nation's schools, Ervin introduced an amendment to the bill that would gut HEW's new guidelines. The Ervin amendment aimed to defend “freedom of choice” programs by stipulating that discrimination could be only said to exist in a school system if a complainant could demonstrate “substantial evidence” of an “intent to exclude.”Footnote 54 If passed, this amendment would have allowed states to continue receiving federal aid while a time-consuming and expensive legal process seeking to demonstrate discriminatory intent could play itself out.

A Senate filibuster brought down the 1966 CRA before the Senate could vote on Ervin's amendment. But in August 1966, Rep. Basil Whitener (D-NC) introduced an amendment to the House version of the bill that was an almost word-for-word copy of Ervin's proposal. Whitener also adopted Ervin's rationale by invoking Hubert Humphrey's defense of de facto segregation, when he proclaimed HEW's new guidelines to violate Congress’ intent when it passed the CRA. Whitener presented his amendment as simply an effort to shore up “free choice” programs.Footnote 55 He was supported on the floor by Rep. Jamie Whitten (D-MS), who described it as defense against “forced integration.”Footnote 56 Rep. William Dorn (R-SC) also appealed to the freedom of choice plans that had been previously validated by HEW. “No child is turned away from any school in the area of South Carolina where my children will be attending,” he claimed. “We have complied with the law.”Footnote 57 Despite minimal pushback from opponents of Whitener's amendment, it failed narrowly on a teller vote, 127-136.Footnote 58

Having lost by such a small margin, Whitener then introduced a new amendment obligating any family with a child they believed to be the victim of discrimination to file a written complaint with the Department of Justice. In this case, Whitener sought to make it more difficult for the Attorney General to take legal action against school districts refusing to enforce HEW's desegregation guidelines. As Rep. Byron Rodgers (D-CO) pointed out when discussing Whitener's proposal, individuals who filed formal complaints were often “subjected to intimidation and harassment.”Footnote 59 Whitener was forcing Black residents to choose between segregated schools and the threats that would come should any resident out themselves as a potential plaintiff in a lawsuit against the state or locality.

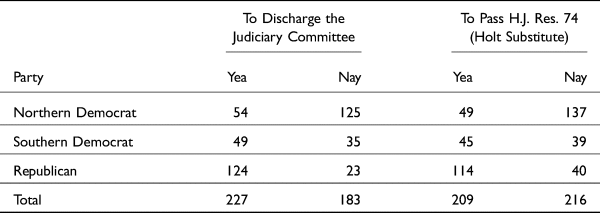

The House passed Whitener's amendment 214-201.Footnote 60 As Table 1 makes clear, it won support from twenty-nine nonsouthern Democrats and 102 of 137 voting Republicans.Footnote 61 Momentum was building in opposition to the new Office of Education guidelines, leading Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield (D-MT) to tell the New York Times in September that HEW was moving “too fast” in its effort to integrate.Footnote 62 The support Whitener's amendment received from Republicans and nonsouthern Democrats was a warning that the pro-civil rights coalition in the House was now under pressure.

Table 1. Desegregation and the CRA of 1966

Source: Congressional Record, 89th Congress, 2nd Session (August 9, 1966): 18738.

By the end of 1967, a similar dynamic emerged in the Senate. In December, Everett Dirksen (R-IL) reminded fellow senators that in Section IV of the 1964 CRA, “we made it plain … that no official of the United States or court of the United States is empowered to issue any order seeking to achieve a racial balance in any school by requiring the transportation of … students from one school to another.” Dirksen spoke during a debate over legislation to amend to the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), which had passed two years prior. His comments served as preamble to an amendment he introduced prohibiting money appropriated by the bill to pay “any costs of the assignment or transportation of students … to achieve racial balance.”Footnote 63 In his effort to keep federal money from being spent on busing, Dirksen was joined by fellow Republicans Peter Dominick (R-CO) and Roman Hruska (R-NE), both of whom also voted for the 1964 CRA. Now they were echoing Dirksen's argument, claiming that the bill they supported was being used to achieve ends they had explicitly disclaimed.Footnote 64

Dirksen's amendment met opposition from senators who, at this point, were still willing to defend busing as the best way to actually desegregate. Jacob Javits (R-NY), for example, attributed his opposition to Dirksen's proposal to the fact that a blanket prohibition would deprive those families who wanted their children bused an opportunity to attend integrated schools.Footnote 65 Clifford Case (R-NJ) took this perspective as well. Passing Dirksen's amendment, he claimed, would amount to “limiting the discretion and impairing the ability of local school boards, the states, and the courts” to receive federal aid if they chose to implement busing programs.Footnote 66 Putting this critique into legislative language, Robert Griffin (R-MI) proposed to revise Dirksen's amendment to say that money appropriated by the bill (H.R. 7819) could be spent on busing as long as a busing program was “freely adopted” by a state or locality.Footnote 67

Making federal expenditures contingent in this way failed to help Griffin's amendment win a majority in the Senate. When it came up for a vote, the Senate deadlocked, 38-38. As a result, the amendment failed. Table 2 breaks the vote down. In this case, nineteen of thirty-one voting Republicans sided with Dirksen's effort to ban federal appropriations for busing. They were aided by thirteen southern Democrats and six Democrats from West Virginia, Ohio, Arizona, Nevada (two), and New Mexico.Footnote 68 As the 1968 election approached, political trends were moving against those who supported HEW's effort to end segregation. In Congress, a bipartisan coalition was forming to prevent the federal government from endorsing school busing.

Table 2. Desegregation and the CRA of 1968

Source: Congressional Record, 90th Congress, 1st Session (December 4, 1967): 34975.

On the presidential campaign trail, Richard Nixon spoke to the growing popular movement against a more forceful attack on structural forms of racial hierarchy. During a press conference in Anaheim, California, Nixon endorsed the Brown decision and made clear that he would not tolerate freedom of choice plans acting as a “subterfuge for segregation.” But he did not stop there. “When the Office of Education goes beyond the mandate of Congress and attempts to use federal funds … for the purpose of integration … with that I disagree,” he continued.Footnote 69 Nixon repeated this position in an October 27 interview on “Face the Nation” when he attacked “compulsory integration.”Footnote 70 In this way, candidate Nixon followed the lead of those in Congress who were cultivating a new “color-blind” approach to civil rights: condemning the most explicit forms of racial discrimination while also condemning the methods adopted for desegregating schools.Footnote 71

Busing fights during the Nixon era

At the end of the 1960s, popular majorities in Congress may have been moving toward Nixon's position, but the Supreme Court was not. In 1968 and 1969, two important decisions forced busing back on the congressional agenda. In the first, Green v. County School Board of New Kent County (1968), a unanimous Court held that “school systems which had been segregated by official action were obligated to accomplish actual integration.”Footnote 72 The freedom of choice plans favored by the emergent “color-blind” coalition in Congress were now judged by the Court to be an inadequate response to de jure segregation. One year later, in Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education (1969), another unanimous ruling called for an immediate end to the system of separate schools existing across the South. Writing for the majority, Chief Justice Warren Berger—a Nixon appointee—declared, “there is no longer the slightest excuse, reason, or justification for further postponement of the time when every school system in the United States will be a unitary one, receiving and teaching students without discrimination on the basis of race or color.”Footnote 73 By early 1970, court-ordered busing was a reality.

In the aftermath of these rulings, members of Congress who had already taken an antibusing position did not simply give up their opposition. Instead, the Court motivated them to double-down on their prior efforts. Senator John Stennis (D-MS) made the first move during a debate over legislation to extend the ESEA when he introduced an amendment that would end the legal distinction between de jure and de facto segregation. If enacted, this amendment would have required northern school districts to follow the same integration rules that governed in the South.Footnote 74 According to Stennis, “equitable” application of the 1964 CRA's antidiscrimination provisions would allow citizens outside the South to “find out whether they want this system of integration.”Footnote 75 Stennis believed—rightly—that northern citizens would turn against busing if it was imposed upon their children.

Complicating matters further, the Stennis amendment was cosponsored by Abe Ribicoff (D-CT), a northern liberal. Ribicoff saw the Stennis proposal as a way to “push Senate liberals toward more dramatic action.”Footnote 76 In a floor speech defending his work with Stennis, Ribicoff accused northerners of “monumental hypocrisy in their treatment of the black man.” “Without question,” he explained, “northern communities have been as systematic and consistent as southern communities in denying the black man and his children the opportunities that exist for white people.”Footnote 77 Ribicoff believed that the federal government must step in to end de facto segregation in the North, and he was not the only person to hold this view. In testimony before the Senate only months before the debate over Stennis’ amendment, Leon Panetta—then running HEW—testified that Congress had “let the North off the hook.” The Washington Post reported that during the hearing, Panetta went so far as to say that “Northern segregation is probably just as much due to official policy as the Southern variety is.”Footnote 78

The Stennis amendment put supporters of civil rights in an awkward political position. Most understood that northern communities would not tolerate what the amendment aimed to accomplish. To vote against the amendment, however, would mean taking a stand against a legal effort to desegregate obviously segregated northern schools. Liberal opponents of the Stennis amendment were thus forced to condemn it for, in the words of Walter Mondale (D-MN), “imped[ing] efforts to eliminate segregation in the south where they have dual school systems.”Footnote 79 Senator Hugh Scott (R-PA) followed this line by introducing a substitute amendment that would remove the equivalence Stennis attempted to draw between de jure and de facto segregation. When it was time to vote, Scott's amendment was rejected, 46-48.Footnote 80 As Table 3 illustrates, it failed because eight northern Democrats and twenty-two Republicans voted with southerners. Senator Jacob Javits (R-NY) then adopted a similar approach in an amendment that would change the wording of the Stennis amendment to protect the legal distinction between northern and southern segregation. Javits’ amendment failed by a larger margin (41-50) than the Scott substitute.Footnote 81

Table 3. Stennis Amendment

Source: Congressional Record, 91st Congress, 2nd Session (February 16, 1970): 3788; 3797; 3800.

Finally, the Senate voted on the Stennis amendment itself. It passed, 56-36, winning support from eleven northern Democrats and twenty-seven Republicans.Footnote 82 The coalition of thirty-six who opposed it showed that many northern legislators refused to support action that would take on the kind of segregation present in their communities. For now, they were saved by changes made to the bill in conference. As Joseph Crespino explains, conferees added provisions to the final version of the ESEA reauthorization which voided the policy implications of the Stennis amendment.Footnote 83 Yet the Stennis fight made clear to all that a significant number of northern legislators feared the consequences of an attack on de facto school segregation.

The legal distinction between “official” and “unofficial” segregation came up again at the end of February as the Senate debated a bill to fund HEW. In this case, by a vote of 42-32, the Senate removed language in the House-passed version of the bill that would have prohibited any money from being spent on busing programs in the South.Footnote 84 In Table 4 (column 1), we show that on this vote, the civil rights coalition held together: twenty-five northern Democrats and sixteen of thirty-one voting Republicans defeated a conservative coalition of fifteen southern Democrats, fifteen Republicans, and two nonsouthern Democrats. In June 1970, a larger coalition emerged to remove similar language that the House had written into a bill funding HEW's Office of Education—as more Republicans signed on (see Table 4, columns 2 and 3).Footnote 85 What these voting results show, overall, is that the pro-civil rights coalition eroded more quickly in the House than the Senate.

Table 4. HEW Funding

Source: Congressional Record, 91st Congress, 2nd Session (February 28, 1970): 5413; (June 24, 1970): 21218; 21228.

The next period of intense debate over busing occurred in late-1971, motivated once again by the Supreme Court. In Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education—another unanimous decision—the justices upheld a lower-court ruling which imposed a busing program on school children in Charlotte. In so doing, they made clear that busing would follow any showing of de jure segregation in a school district. As Gary Orfield explains, what made this case so important was that “the busing remedy would now become available in the north, too, once lawyers proved de jure violations in a given community.”Footnote 86

The implications of Swann were felt almost immediately. In September 1971, Stephen J. Roth, a district court judge in Detroit, found that public institutions throughout the city enforced a system of segregated schooling. “Governmental actions and in action at all levels … have combined with those of private organizations … to establish and maintain the pattern of residential segregation through the Detroit metropolitan region,” he wrote.Footnote 87 Roth went on to require a metropolitan busing program for the purpose of ending school segregation in the city. The congressional response to Roth's order was quick and fierce. In early November 1971, during House debate over legislation to extend the Higher Education Act (H.R. 7248), Rep. William Broomfield (R-MI) introduced an amendment that would “postpone the effectiveness of any U.S. District Court order requiring the forced busing of children to achieve racial balance until all appeals to that order have been exhausted.”Footnote 88 As a representative from Michigan, Broomfield sought to prevent the busing program mandated by Judge Roth. Broomfield's amendment was cosponsored by five Democrats from the Michigan delegation—William D. Ford, Martha Griffiths, James O'Hara, Lucien Nedzi, and John Dingell. Gerald Ford (R-MI) also spoke for it.Footnote 89 These supporters backed Broomfield even though the language of his amendment was “drafted so broadly” that it would have also prevented the implementation of busing programs where it was clear that a school system was intentionally segregating students.Footnote 90

Despite the support Broomfield's amendment received from ostensible civil rights liberals in the Michigan delegation, it also drew opposition from members who recognized the double standard that would be written into law should this amendment be enacted. Two Black House members took the lead. Rep. Shirley Chisholm (D-NY) condemned supporters for being fine with busing “black and Spanish-speaking children” but expressing outrage as soon as “a certain segment that have been the beneficiaries of the status quo in America” were affected.Footnote 91 Rep. Charlie Rangel (D-NY) warned about what could happen if members of Congress who disagreed with a particular court order simply “legislated a new one.”Footnote 92 Regardless of these concerns, Broomfield's amendment passed overwhelmingly.Footnote 93 As Table 5 (column 1) makes clear, Republicans and southern Democrats backed the amendment by huge margins. Most importantly, however, almost 40% of those nonsouthern Democrats who voted also supported Broomfield's proposal.

Table 5. Higher Education Act (House)

Source: Congressional Record, 92nd Congress, 1st Session (November 4, 1971): 39312; 39318; 39317; 39318.

Opposition to busing from members of the pro-civil rights coalition reemerged during a debate over an amendment offered by Rep. John Ashbrook (R-OH). His proposal blocked federal funds from being used for the purpose of busing.Footnote 94 States and cities could continue busing if they chose, but they would need to pay all of the costs associated with it. Fellow Republican Marvin Esch (R-MI) tried to limit the impact of Ashbrook's proposal by stipulating that the prohibition would not apply in places where “a local educational agency” was “carrying out a plan of racial desegregation … pursuant to the order of a court of competent jurisdiction” (i.e., in the South).Footnote 95 Esch's revision failed in a lopsided vote, 146-216 (Table 5, column 2). Rep. Edith Green (D-OR) then expanded the Ashbrook amendment by adding language preventing the federal government from requiring states to implement desegregation orders pursuant to the 1964 CRA. Even though it undermined a central goal of the CRA, Green's amendment passed, 231-126 (Table 5, column 3).Footnote 96 Soon thereafter, the House voted to support the now-expanded Ashbrook amendment by an almost identical margin, 234-124 (Table 5, column 4).Footnote 97 All of these votes were “conservative coalition” votes: majorities of both southern Democrats and Republicans opposed a majority of northern Democrats. More broadly, by the end of 1971, a bipartisan, interregional alliance had emerged in the House to stand in the way of all federal support for busing.

The growing popular backlash against “forced busing” made it an appealing campaign issue for Richard Nixon's 1972 reelection. Senator Stennis (D-MS) telegraphed the strategy opponents would pursue in a floor speech on February 24, 1972: “We now hear much less often the term ‘de jure’ because it increasingly appears that most segregation in northern schools is, as it was formerly in southern schools … created by state action.”Footnote 98 The plan, once again, would be to simultaneously oppose busing and insist that northern cities face the same rules as those governing in the South. Doing so, Stennis understood, would motivate deep public anger among many northern white voters who did not want their children bused.

Nixon endorsed this strategy in a March 17 address, during which he called on the legislative branch to “establish uniform national criteria” for determining when a school was practicing racial segregation. In the same address he also called for a moratorium on all busing orders until the legislative branch handed down specific guidelines.Footnote 99 The Nixon administration appeared to be following the House's lead by forcing members to either implement a policy that would be imposed on North and South alike, or to vote down busing altogether. He also played for time by challenging members to deny the Court's power to impose busing in places where judges determined that school segregation required an immediate remedy.

Even before Nixon gave this speech, the Senate was struggling through a debate over the Higher Education bill, passed by the House, which included the Ashbrook–Green amendment. Senators Mike Mansfield (D-MT) and Hugh Scott (R-PA), who opposed the House bill, were pushing their own version. Their substitute did not include the Ashbrook–Green amendment because, as Senator Scott warned, it would “have the practical effect of repealing Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.” Instead, he and Mansfield proposed new language that would “solidify the constitutional standard suggested by the Swann case … that the Constitution cannot be read to require transportation to achieve desegregation ‘when the time or distance of travel is so great as to risk either the health of the children or significantly impinge on the educational process.’”Footnote 100

After a prolonged debate over the merits of the Mansfield–Scott substitute, during which members rehashed old arguments about forms of residential segregation North versus South, voting commenced on a series of proposed revisions to this new version of the Higher Education Act.Footnote 101 First, in an overwhelming 79-9 vote, the Senate endorsed the spirit of the Broomfield amendment by delaying, for 16 months, implementation of all court-ordered busing plans (see Table 6, column 1).Footnote 102 Next, the Senate voted to gut an amendment authored by James Allen (D-AL) formally opposing any federal effort to assign students to schools for the purpose of achieving racial balance (Table 6, column 2).Footnote 103 The Senate also voted down—by a small margin—an effort to extend the moratorium on court-ordered busing plans until the Supreme Court could rule on them one-by-one (Table 6, column 3).Footnote 104 Here, Republicans were almost evenly split, but northern Democrats provided enough opposition to defeat the amendment. Overall, on these votes, the pro-civil rights coalition held. Finally, on March 1, the Senate passed and returned to the House an amended version of the Higher Education Act by a vote of 88-6.Footnote 105

Table 6. Higher Education Act (Senate)

Source: Congressional Record, 92nd Congress, 2nd Session (February 24, 1972): 5490; (February 29, 1972): 5982; 6006.

The House and Senate now stood some distance apart. When the Senate-passed version returned to the lower chamber, members immediately condemned its “weakened” antibusing language. Rep. Broomfield, in particular, took issue with the changes made to his amendment, claiming that “The Senate … has adopted a version of our amendment which is both inadequate in scope and grossly inequitable in application.” According to Broomfield, the moratorium language written into the Senate bill would only apply in those “limited situations in which a court might order transfers across school district lines.” Furthermore, he held that the Senate bill introduced “a host of inequities” in how it handled busing orders within a given school district. “They [Senators] are attempting to evade the clear intent and purpose of the overwhelming majority of the House,” Broomfield concluded.Footnote 106

Accordingly, Broomfield and other House members insisted on a motion to instruct members of the conference committee to insist that the specific antibusing language included in their version also appear in the final bill.Footnote 107 The House passed his motion to instruct by a 272-140 vote.Footnote 108 In May, as the conference committee was nearing completion, the House once again tried to insist on its own version. By a vote of 275-125 vote, a decisive majority once again endorsed the blanket prohibitions on federal support for busing mandated by the Ashbrook–Green amendment.Footnote 109 Table 7 illustrates the vote coalitions for both motions to instruct. These were once again conservative coalition votes: large majorities of both southern Democrats and Republicans opposed majorities of northern Democrats. And although northern Democrats, as a whole, continued to support busing, between 36 and 42% of them took an antibusing position.Footnote 110

Table 7. Higher Education Act (House Motions to Instruct and Final Passage)

Source: Congressional Record, 92nd Congress, 2nd Session (March 8, 1972): 7562; (May 11, 1972): 16842; (June 6, 1972).

In the end, as Senator Peter Dominick (R-CO) explained on the Senate floor during consideration of the compromise measure, the best that could be worked out was a “modified” Broomfield amendment. The new language would “sta[y] the effectiveness of busing orders until all appeals are exhausted, or the time for appeals has run, effective to January 1, 1974.”Footnote 111 Although the Ashbrook–Green amendment was not included in the compromise measure drafted in the Senate, the bill did stipulate that local officials who sought federal aid for busing programs would need to formally request money. Finally, the bill barred the federal government from “pressuring” local school boards into implementing busing programs.Footnote 112

These changes drew opposition from a few liberals, such as Senator Ted Kennedy (D-MA), who expressed opposition to any version of the Broomfield language. Also opposed were conservatives such as Senator Robert Griffin (R-MI), who sought language closer to what the House had passed. On May 23, Griffin forced the Senate to vote on a motion to recede from the modified Broomfield language. His motion failed, 44-26.Footnote 113 Then, on May 24, the Senate passed the Mansfield–Scott substitute, 63-15.Footnote 114 Despite howls of protest from aggrieved members of the House, the new version of the Higher Education Act passed in that body by a vote of 218-180 on June 8.Footnote 115 Here, majorities of northern Democrats and Republicans opposed a majority of southern Democrats.

The last busing fight to consume Congress before the November election concerned legislation proposed by Nixon in his March address on busing. The “Equal Education Opportunities Act,” according to Nixon, would reaffirm the unconstitutionality de jure segregation; “establish criteria for what constitutes a denial of equal opportunity”; “establish priorities of remedies for schools that are required to desegregate with busing to be required only as a last resort, and then under strict limitations”; and “provide for concentration of federal school-aid funds specifically on the areas of greatest educational need.”Footnote 116 This was, in short, an effort to avoid substantial desegregation. To soften that blow, Nixon proposed more aid to schools serving nonwhite students.

The House acted on Nixon's proposal by writing a bill (H.R. 13915) stipulating that any school's failure to “attain a balance, on the basis of race, color, sex, or national origin of students … shall not constitute a denial of opportunity.” Students assigned to an “imbalanced” neighborhood school would not be categorized as having been denied equal educational opportunities unless it could be proven that such assignment was “for the purpose of segregating students.”Footnote 117 Finally, the bill made clear that students in the sixth grade or below were prohibited from being bused beyond “the school closest or next closest to his or her place of residence.” Students older than that were eligible for busing beyond the “next closest” school only after demonstrating “clear and convincing evidence that no other method will provide an adequate remedy.”Footnote 118 According to Rep. Paul Quie (R-MN), the busing language in the bill made it “about as controversial” as any legislation “this body has considered.”Footnote 119 Rep. William McCulloch (R-OH)—coauthor of the 1964 CRA—called it “repugnant to the Constitution.”Footnote 120

Despite the already-strong antibusing language written into H.R. 13915, some House members remained unsatisfied—in particular, once again, Reps. Ashbrook and Green. To further clarify his deep opposition to busing for the purposes of integration, Rep. Ashbrook offered an amendment making the “neighborhood school,” as he described it, “the normal and appropriate place to assign a student.”Footnote 121 Language like this, Rep. Rangel (D-NY) noted, would “restrict” public school assignments so as to preserve segregation. In so doing, he claimed, Ashbrook's amendment would undermine the aim and purpose of busing.Footnote 122 Despite its extremely restrictive language, Ashbrook's amendment passed, 254-131.Footnote 123 As Table 8 (column 1) indicates, this was a conservative coalition vote: large majorities of both southern Democrats and Republicans opposed a majority of northern Democrats. Rep. Green moved next to delete the provision stipulating differential treatment for students above and below the sixth grade, thereby preventing busing as a remedy for all school-age children.Footnote 124

Table 8. Equal Education Opportunities Act

Source: Congressional Record, 92nd Congress, 2nd Session (August 17, 1972): 28873; 28907.

Then, in a 245-141 vote, the House adopted another Green amendment to prevent the Attorney General from reopening past desegregation cases to ensure that the school districts in question remained complaint with existing antisegregation laws (Table 8, column 2).Footnote 125 This, again, was a conservative coalition vote: large majorities of southern Democrats and Republicans opposed a (larger) majority of northern Democrats. When the House voted, 283-102 to pass H.R. 13915, it went on record supporting the “strongest” antibusing language “ever passed.”Footnote 126

By this time, the Senate had already acted on multiple occasions to rein in antibusing bills passed by the House. Members were therefore never going to vote this bill into law. In this case, however, the upper chamber went further than usual, as civil rights liberals mounted a successful filibuster of H.R. 13915. Prior to the cloture vote, supportive southern Democrats explained that all they wanted was a “uniform standard” to guide desegregation policy. At the same time, however, they condemned “this useless busing in order to achieve racial balance.” Senate opponents of the bill, led by Jacob Javits (R-NY), argued instead that the bill would “undo everything” that had been accomplished since the 1964 CRA was passed. “Racial imbalance is nothing which the United States can redress,” Javits conceded. “The only thing we are debating is the illegality of segregation.”Footnote 127

Enough of the Senate accepted the view that the House bill served as a cover for protecting segregated schools that three separate cloture votes failed to win the required support to end debate. Each time, a majority of the Senate voted in support of cloture—but as the data in Table 9 indicate, it fell well short of the 2/3 necessary, as a large majority of northern Democrats voted in opposition.Footnote 128 In sum, the same coalition that had effectively defanged House antibusing language now came together to kill Nixon's “Equal Opportunities bill.”

Table 9. Cloture Votes on Equal Education Opportunities Act

Source: Congressional Record, 92nd Congress, 2nd Session (October 10, 1972): 34504; (October 11, 1972): 34788; (October 12, 1972): 35330.

For a brief time after the election of 1972, busing became less of a national issue. As Gary Orfield notes: “Although the President promised to give the matter ‘highest priority’ in 1973, antibusing legislation may well have been one of the many casualties of Watergate.”Footnote 129 The only meaningful role antibusing played in Congress during the first half of the 93rd Congress (1973–74) was through amendments introduced in 1973, after the Arab oil embargo had taken hold. Busing opponents used fuel scarcity as a pretext to undermine school integration. For example, Sen. Jesse Helms (R-NC) twice attempted to add amendments to promote the conservation of gasoline through the reduction in school busing. He failed each time.Footnote 130

On the House side, John Dingell, Jr. (D-MI) offered a similar amendment, proposing to ban the allocation of petroleum for the busing of students farther than the school nearest to their home. A number of liberal House members criticized Dingell, with Rep. Bella Abzug (D-NY) calling it “scandalous demagoguery.” But the amendment passed, 221-191, with enough northern Democrats joining with large majorities of southern Democrats and Republicans to generate a majority.Footnote 131 The National Energy Emergency Act (H.R. 11450), with the Dingell amendment attached, would go on to pass in the House. Ultimately, however, it was set aside in favor of the (conference-amended) Senate version (S. 2589; National Emergency Petroleum Act), which did not include a Dingell-like provision.

Busing would become prominent on the congressional agenda again in 1974, thanks to the need to reauthorize elements of the ESEA. Although there were many issues in play, not the least of which was resolving funding allocations across rural, urban, and suburban coalitions, busing would become a significant cleavage issue. This worked to the benefit of President Nixon, who was being battered by the Watergate scandal and sought ways to shore up his conservative support and prevent the growing momentum for impeachment.Footnote 132 On March 26, 1974, Rep. Marvin Esch (R-MI) began the antibusing push by offering an amendment to the House Education and Labor Committee bill (H.R. 69) that would strike out a section and replace it with the text from The Equal Educational Opportunities Act (H.R. 13915) that the House passed on August 17, 1972. The effect of the Esch amendment would be to prohibit busing for the purpose of achieving racial balance. After a lengthy discussion, and a failed attempt by three moderates—Reps. John Anderson (R-IL), Lunsford Preyer (D-NC), and Morris Udall (D-AZ)—to find a middle-ground solution,Footnote 133 the Esch amendment passed, 293-117.Footnote 134 The following day, Rep. John Ashbrook (R-OH) followed up on Esch's efforts by (once again) offering an amendment to prohibit the use of any federal funds to implement busing plans—even when there was an express written request by the appropriate school board. This too passed, 239-168.Footnote 135 As the top portion of Table 10 indicates, both cases were classic conservative coalition votes: large majorities of southern Democrats and Republicans opposed a majority of northern Democrats. With the two antibusing amendments attached, the overall bill (H.R. 69 as amended) passed easily, 380-26.Footnote 136

Table 10. Busing and the Education and Secondary Education Act Amendments, 1974

Source: Congressional Record, 93rd Congress, 2nd Session (March 26, 1974): 8281–82; (March 27, 1974): 8505–6.

Source: Congressional Record, 93rd Congress, 2nd Session (May 15, 1974): 14925; 14926.

Busing also emerged as an issue in the Senate proceedings on the amendments to the ESEA (S. 1539). The antibusing position would be anchored by Sen. Edward Gurney (R-FL), who offered an amendment similar to that of Esch's in the House. Gurney's amendment would, among other things, prohibit the forced busing of students beyond the school next nearest to their home. An impassioned debate took place on May 15, 1974, with Sen. Edward Brooke (R-MA)—the first Black senator since Blanche Bruce (R-MS) during the Reconstruction era—leading those members willing to defend the program.Footnote 137 Among other things Brooke stated: “The separate but equal doctrine of Plessy against Ferguson that divided America for 60 years must never return. Yet the measures before us contain the prescription for abandoning equal educational opportunities and for returning to separate but equal facilities.”Footnote 138 Finally, Sen. Jacob Javits moved to lay Gurney's amendment on the table, which passed 47-46.Footnote 139

The Senate then adopted an amendment by Sen. Birch Bayh (D-IN), which would require a U.S. court to find alternative remedies inadequate before implementing school busing plans to remedy de jure segregation. Bayh's amendment—which left the final say on desegregation controversies to the courts—was moderate in orientation and passed by a sizable majority, 56-36.Footnote 140 The details of the votes appear in the bottom portion of Table 10. Although the tabling vote broke down in typical conservative-coalition fashion, the vote to adopt the Bayh amendment received majority support from all three blocs. The following day, some additional amendments succeeded (moderate in nature) while others failed (conservative in nature), before the overall bill (S. 1539 as amendment) passed, 81-5.Footnote 141

With two different chamber bills passed, a conference committee was appointed to iron out the differences.Footnote 142 Although the House members on three separate occasions instructed their conferees to insist on the House bill's provisions, the House conferees mostly went along with the Senate version. Although the “next nearest” busing provisions of the Gurney amendment were adopted, the conference committee also included the language of the Bayh amendment along with provisions to maintain the court's ultimate constitutional authority to ignore busing bans in order to protect children's rights.Footnote 143 The conference bill passed easily in each chamber,Footnote 144 and President Gerald Ford signed it into law.Footnote 145

House conservatives were not pleased. Rep. Ashbrook captured their thinking: “On a scale of one to 100 we gave up 95 points and they gave up five.”Footnote 146 Conservative anger was somewhat muted, however, as external factors conspired to take the sting out of the perceived defeat. An entry from CQ Almanac describes this:

One of the key factors in dissipating House opposition to the conference agreement on busing was a July 25 Supreme Court decision [Milliken v. Bradley] striking down a lower court order calling for cross county busing between Detroit, Mich., and 53 surrounding communities. The Court, in a 5-4 decision, declared that boundary lines could be ignored only where each school district had been found to practice racial discrimination or where the boundaries had been deliberately drawn to promote racial segregation.

The decision was a major disappointment to civil rights advocates who argued that in urban areas successful school desegregation could be achieved only by merging the predominantly black school population of the inner city with the heavily white population of the suburbs.Footnote 147

The Milliken v. Bradley (1974) ruling effectively allowed segregation if it was not an explicit policy of each school district, thereby endorsing the supposed distinction between de jure and de facto segregation. School systems were not responsible for desegregation across district lines unless there was clear evidence that they each had deliberately engaged in a policy of segregation. This meant that the issue of busing between cities and suburbs was settled—with antibusing advocates in suburbs coming out on top—and left future conflict over busing to be within-city only. Vice President Gerald Ford—who would ascend to the top job in a few short weeks—said in July 1974 that the Milliken decision was a “victory for reason” and “a great step forward to finding another answer to quality education.”Footnote 148

Busing battles after Nixon

Much of the first half of the 94th Congress (1975–76) passed without any additional conflict over busing. The issue emerged on the national stage again in September 1975, when President Ford complained that the courts were not following the law he signed in August 1974.Footnote 149 Ford's statement presaged fireworks that would occur later that month in the Senate, as two amendments—offered by Sens. Joe Biden (D-DE) and Robert Byrd (D-WV)—would make national headlines again. The Biden–Byrd amendments indicate that the Senate was now coming to mirror the House's more conservative position on busing.

During the debate on the Departments of Labor and Health, Education, and Welfare Appropriation Act, Sen. Biden, who had been under fire in his home state for his liberal positions on busing,Footnote 150 offered an amendment that no funds shall be used to require any school, as a condition for receiving federal funds, to assign teachers or students to schools for reasons of race. He characterized this an antibusing amendment because it would prevent HEW from mandating busing.Footnote 151 (Biden was also clear that his amendment would not impinge on the federal courts.) Despite senators being confused about the language, and despite opposition from Sens. Brooke, Hubert Humphrey (D-MN), and other liberals, the Biden amendment passed, 50-43.Footnote 152 A week later, Sen. Byrd offered a simple amendment that would prohibit funds from being used to require, directly or indirectly, the transportation of any student to a school other than that which is nearest to his or her home and which offers the courses necessary to remain in compliance with Title IV of the CRA of 1964. Similar to the Biden amendment, Byrd's amendment would restrict HEW but not the courts. After some sharp debate, it passed 51-45.Footnote 153

The following day, Sen. Biden gained the floor and noted that “there is a good deal of confusion in the Chamber at this point, and I suspect that I am in large part responsible for some of that confusion.” He went on to say that numerous senators criticized the language in his September 17 amendment and believed “in addition to preventing HEW from directly or indirectly being able to bus children, I may also have precluded HEW from being able to assign teachers, from being able to redress racial imbalances within classrooms.” He then offered another amendment to clarify his intent, which was that “HEW will not be able, directly or indirectly, to put a child on a school bus to redress any kind of imbalance, to redress any kind of alleged violation of title VI of the Civil Rights Act.”Footnote 154 After a failed tabling motion, offered by Sen. James Allen (D-AL), the second Biden amendment passed 44-34.Footnote 155 As the top portion of Table 11 indicates, all three amendment votes were conservative coalition votes; however, the second Biden vote was a retrenchment—as the first Biden amendment went too far in inhibiting desegregation generally—and thus the yea–nay coalitions shifted.

Table 11. Antibusing Amendments, 1975

Source: Congressional Record, 94th Congress, 1st Session (September 17, 1975): 29123; (September 24, 1974): 30045; (September 25, 1975): 30365.

Source: Congressional Record, 94th Congress, 1st Session (December 4, 1975): 38718; 38718–19.

The appropriations act passed 60-18, but when it went to conference both Biden amendments were dropped.Footnote 156 The Byrd amendment was not. In response, Rep. Daniel Flood (D-PA) tried to replace Byrd's amendment with language accepted during the previous Congress: schools other than those “nearest or next nearest” to a child's home. It failed, 133-259.Footnote 157 The House then concurred with the Byrd amendment, 260-146.Footnote 158 The bottom portion of Table 11 reports the breakdowns; both were conservative coalition votes, with small majorities of northern Democrats opposing large majorities of both Republicans and southern Democrats. The House then voted 321-91 to agree to the conference report.Footnote 159 The Senate followed by approving via voice vote.Footnote 160 Liberals tried to put the best spin on things. Rep. Flood noted (correctly): “None of this is binding on the courts.” And Rep. Silvio Counte (R-MA) added: “To change busing, you'll have to change the Constitution.”Footnote 161 Counte's statement would portend near-future congressional action.

The second half of the 94th Congress was considerably quieter on the busing front. The major initiative occurred not in Congress, but via the Executive branch. President Ford had been considering a statement on busing for some time, and in November 1975, he had directed the Justice Department and HEW to identify ways to minimize court-ordered busing. After 8 months, the Justice Department drafted legislation that came to be called “The School Desegregation Standards and Assistance Act of 1976.” President Ford sent this proposal to Congress on June 24, 1976.Footnote 162 According to CQ Almanac, “The legislation would set guidelines and time limits for busing orders and establish a national advisory committee to assist school systems in desegregating voluntarily.”Footnote 163 Unlike the legislation proposed by President Nixon, which produced serious squabbling in Congress and was blocked in the end only by a Senate filibuster, Ford's legislation was sent to committee in both the House and Senate. There it died a quiet death.Footnote 164 Beyond the president's legislative initiative, Congress produced nothing new on busing in 1976. Various antibusing amendments were offered in the Senate—by William Roth (R-DE), Bob Dole (R-KS), Jesse Helms (R-NC), and Strom Thurmond (R-SC)—but all were defeated.

The 95th Congress saw the Democrats achieve unified party government again, thanks to the election of President Jimmy Carter, but busing continued to be an issue. Carter himself took no position on the issue, and offered no legislation unlike Nixon and Ford before him. But in June 1977, Congress would push back against a HEW announcement that communities would need to use techniques such as “pairing” of schools—where mostly Black and mostly white schools near each other would combine student bodies—to comply with civil rights laws.Footnote 165 Antibusing legislators referred to these consolidation techniques as a “loophole” that HEW had found to get around the provisions of the Byrd amendment from the previous Congress. In response, Rep. Ronald Mottl (D-OH) offered an amendment to the Departments of Labor and Health, Education, and Welfare Appropriations Act to prohibit the withholding of funds from school districts that refused to merge or consolidate Black and white schools to facilitate desegregation if the plan required that pupils be bused to a new school. It passed 225-157.Footnote 166 Liberals, smarting from the defeat, downplayed the antibusing effort as little more than a protest against HEW's procedures. For example, Rep. David Obey (D-WI) said: “This amendment has nothing to do with court-ordered busing. It ain't going to stop one bus.”Footnote 167

In the Senate, Edward Brooke (R-MA) sought to eliminate the busing elements from the appropriations legislation. He first offered an amendment to strike all antibusing language in the bill. This failed, 42-51.Footnote 168 He then narrowed his goal, by offering an amendment that would restore the use of busing only for the pairing (and a similar technique, clustering) of schools. Thomas Eagleton (D-MO) moved to table this second Brooke amendment, which succeeded, 47-43.Footnote 169 As Table 12 indicates, the roll calls on the Mottl and two Brooke amendments were once again conservative coalition votes, as majorities of southern Democrats and Republicans joined against a majority of northern Democrats to restrict busing. In each case, though, 30–37% of northern Democrats voted with the conservatives—which proved pivotal for the outcome on each roll call.Footnote 170 Finally, the appropriations act was adopted in December 1977 with the language from the Mottl amendment included.Footnote 171 Congress had effectively closed the loophole that HEW had uncovered.

Table 12. Antibusing Votes, 1977

Source: Congressional Record, 95th Congress, 1st Session (June 16, 1977): 19409; (June 28, 1977): 21260; 21263–64.

The remainder of the 95th Congress maintained the status quo. A potential, landmark bill was reported out of the Senate Judiciary Committee on September 21, 1977, on an 11-6 vote.Footnote 172 Sponsored by Sens. William Roth (R-DE) and Joe Biden (D-DE), the bill (S. 1651) would seek to restrict the federal courts’ authority to order busing. The Delaware senators were thus acting upon the reality of the time: attacking HEW might provide some useful position-taking benefits, but to truly affect busing, Congress would have to take on the courts. Per the CQ Almanac, the bill would:

would bar any court from ordering busing for desegregation purposes without first determining that “a discriminatory purpose in education was a principal motivating factor” for the violation the busing was designed to correct.

The bill also specified that the court could not order more extensive busing than “reasonably necessary” to restore the racial composition of “particular schools” to what it would have been if there had been no discrimination. Before ordering busing the court would have to make specific written findings of “discriminatory purpose” and of how the racial composition of the affected schools varied from what it would have been without the discrimination.