In nutritional epidemiology, the term ‘Western diet’ has come to receive a negative connotation, representing a dietary culture high in saturated fats, sugar, refined and processed foods and low in fibre( Reference Popkin 1 ). A paper published in 2002, mapping intake of food groups in ten European countries, confirmed the negative picture, especially for the Nordic countries, where the diet was high in soft drinks, margarines, alcohol and processed meat( Reference Slimani, Fahey and Welch 2 ).

However, the Nordic diet is not only characterized by these non-beneficial food components: health-enhancing elements of the Nordic dietary culture have also been found, with special focus given to the consumption of dark bread, an inherent part of the traditional Nordic diet( Reference Grasten, Juntunen and Poutanen 3 ). But other such items exist as well, and a list of criteria for defining food items that are part of a Nordic diet has been described( Reference Bere and Brug 4 ):

-

1. ‘Ability to be produced locally over large areas within the Nordic countries without usage of external energy, e.g. for the production of greenhouses.

-

2. A tradition as a food source within the Nordic countries.

-

3. Possessing a better potential for health-enhancing effects than similar foods within the same food group.

-

4. Ability to be eaten as foods, not only in small amounts as dietary supplements (e.g. spices)’.

Two recent studies examining an index of food items, fulfilling these criteria, found a decrease in overall mortality with above-median consumption of these components in middle-aged Danes( Reference Olsen, Egeberg and Halkjaer 5 ), as well as an inverse association with colorectal cancer, albeit only significant for women( Reference Kyro, Skeie and Loft 6 ). A Swedish intervention trial comparing a habitual, Western diet and a Nordic diet found statistically significant decreases in cholesterol and body weight in mildly hypercholesterolaemic subjects( Reference Adamsson, Reumark and Fredriksson 7 ), and a multi-centre intervention study in four Nordic countries with an isoenergetic healthy Nordic diet found an improved lipid profile and a beneficial effect on low-grade inflammation compared with an average Nordic diet( Reference Uusitupa, Hermansen and Savolainen 8 ). Taken together, these findings suggest that a preventive potential may exist in promoting a healthy, Nordic diet. However, we have not been able to identify any previous papers examining whether the items included in such a diet are exclusively geographically related to the Nordic countries, constituting a significant part of the diet only here, or to what extent they are inherent components of the diet in other European countries as well. This would suggest an even broader preventive potential of these food items, as consumption could be encouraged in their local environments, rather than the introduction of unfamiliar components from other regions which may not be as easily incorporated into local dietary culture( Reference da Silva, Bach-Faig and Raido 9 ).

Therefore, the aims of the present study were to describe the intake of seven a priori defined probable healthy components of a Nordic diet culture in the ten countries participating in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) and to investigate whether they are consumed more frequently in the Nordic countries or constitute part of the diet in other European countries as well. The items included in the current paper are: apples/pears, berries, cabbages, dark bread, shellfish, fish and root vegetables. Information regarding consumption of these foods has been obtained through 24 h diet recall (24HDR).

Methods and material

Study participants

EPIC is a multi-centre cohort study, initiated with the purpose of investigating the relationship between nutrition and incidence of cancer and other chronic diseases. The cohort consists of participants from ten European countries (Denmark, France, Germany, Great Britain, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain and Sweden). The population and inclusion of participants has been described elsewhere( Reference Riboli, Hunt and Slimani 10 ). In brief, the cohorts consist of 519 978 men and women, recruited from 1992 to 2000. Most are recruited from the general population( Reference Riboli, Hunt and Slimani 10 ), but in France, Norway, Utrecht (the Netherlands) and Naples (Italy), only women were included. In Spain and some Italian centres, a large proportion of the participants were blood donors, and in Oxford (Great Britain), some of the participants were recruited from a selected, health-conscious population consisting of vegetarians, vegans, etc. All participants gave written informed consent, and the study was approved by the local ethical committees of the participating countries.

The present study is based on a subgroup of the cohort, consisting of persons aged 35–74 years, who participated in a single 24HDR between 1995 and 2000. Detailed information regarding selection and characteristics of participants can be found elsewhere( Reference Slimani, Kaaks and Ferrari 11 ). Briefly, this population consists of a random sample from each country, representing 5–12 % of local cohort participants (1·5 % in Great Britain), weighted according to the cumulative number of cancer cases expected over 10 years of follow-up per gender and age stratum. The sampling procedure aimed at an equal distribution of season and day of interview to control for day-to-day and seasonal variation in dietary intake. In some centres (Ile-de-France, France; Potsdam, Germany; all centres in the Netherlands and Denmark, and to some extent in the remaining French centres; Heidelberg, Germany; and Ragusa, Italy), participants in the 24HDR were recruited without prior knowledge when participating in the baseline examination, in order to avoid changes in dietary habits. This was not possible in all centres, and in the remaining centres, participants were invited to take part in a 24HDR before study inclusion or were re-contacted. Here, the 24HDR were conducted using a face-to-face interview or via telephone (Norway only), but participants were not informed beforehand about the period of interest, in order to avoid changes in dietary habits( Reference Slimani, Kaaks and Ferrari 11 ).

For the present study, individuals with missing information on gender were excluded (n 24). This resulted in a total study population of 36 970 individuals.

Dietary data

Each participant completed a single 24HDR. Information regarding dietary intake of the included components was collected using a computerized software program: EPIC-SOFT, the details of which can be found elsewhere( Reference Slimani, Deharveng and Charrondiere 12 , Reference Slimani, Ferrari and Ocke 13 ). This software consisted of the same structure and translated interface across countries, in order to assess dietary intakes in a standardized manner. The program was adapted for each country in terms of foods and recipes included. Depending on the country, 150–200 food items and 150–300 recipes were entered. A total of ninety trained interviewers in the ten countries assisted the participants in completing the interview.

Information regarding all food and beverage items consumed during the recalled day was collected, entered and coded. During the interview, each reported food item was described and quantified. Methods of quantifying portion sizes were standardized between countries using photographs of weight and volume, standard units, household measures or exact amounts. Those participating via telephone interview were mailed these pictures beforehand. For each food item, the final amount was calculated taking into account quantification, cooking method and edible part in order to obtain the total mass consumed. The purpose of the 24HDR was to acquire good estimates of mean food intake at population level, and therefore mean intake of each food item is the primary measurement of interest in the present study.

Foods were classified according to seventeen main groups and 124 subgroups. Here, seven subgroups are considered: cabbages, apples/pears (not including juices), berries (not including jams and marmalades), dark bread, fish, shellfish and root vegetables. The main food items contributing to each subgroup, presented by country, are shown in the online supplementary material (Supplementary table s2).

Statistical methods

Analyses were conducted separately for men and women. The statistical software package SAS version 9·1 for Windows or TextPad was used for all analyses. The study included calculations of mean food intake for each EPIC centre and country, as well as for the total study population (termed EPIC mean) for comparative purposes. Furthermore, we computed the percentage of overall food groups (vegetables, fruit, bread, meat) which was constituted by the included dietary items. For fish and shellfish, this was calculated as a percentage of total meat intake defined as meats, fish and shellfish. All analyses were weighted by day and season of data collection to correct for discrepancies in these between centres. Weighting by age did not materially alter the results and was therefore not included.

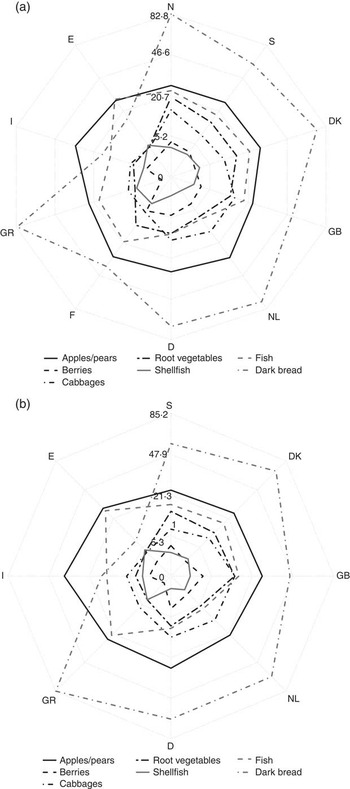

A graphical representation of the mean intake of each food item in each centre along a north–south gradient is used to illustrate differences and similarities in food patterns across countries and by gender. For each food item, mean intake is compared with the EPIC-wide mean intake of the food item. Furthermore, spider plots are used to illustrate the consumption variability of each dietary component across participating countries.

We defined the following regions prior to analyses: (i) Northern European countries as Norway, Sweden and Denmark; (ii) Central European countries as Great Britain, the Netherlands, Germany and France; and (iii) Southern European countries as Greece, Italy and Spain.

Results

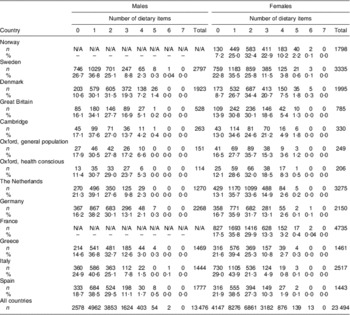

A total of 36 970 participants (64 % women) from the EPIC cohort were included in the present study, representing all ten EPIC countries. The distribution of study participants was fairly even between Northern, Central and Southern European countries (Table 1).

Table 1 Number and proportion (%) of participants from each country in the present study on consumption of predefined ‘Nordic’ food items; men and women aged 35–74 years, constituting a random sample of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) cohort

N/A, not applicable.

Quantity of intake is explored in Fig. 1, where mean intake of each food item by country and gender is shown compared with the gender-specific EPIC mean. The percentage of each main food group consumed as one of the seven included healthy Nordic food items is presented in spider plots by gender (Fig. 2). Finally, the proportions of participants consuming at or above EPIC means of the seven included food items is presented by country (Table 2).

Fig. 1 Sex-specific (![]() , female (F);

, female (F); ![]() , male (M)) mean intake in each country*, compared with EPIC mean (– – –, F; ———, M), of seven predefined ‘Nordic’ food items: (a) apples/pears, (b) berries, (c) cabbages, (d) root vegetables, (e) shellfish, (f) fish and (g) dark bread; men and women aged 35–74 years, constituting a random sample of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) cohort. *N = Norway, S = Sweden, DK = Denmark, GB = Great Britain, NL = the Netherlands, D = Germany, F = France, GR = Greece, I = Italy, E = Spain

, male (M)) mean intake in each country*, compared with EPIC mean (– – –, F; ———, M), of seven predefined ‘Nordic’ food items: (a) apples/pears, (b) berries, (c) cabbages, (d) root vegetables, (e) shellfish, (f) fish and (g) dark bread; men and women aged 35–74 years, constituting a random sample of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) cohort. *N = Norway, S = Sweden, DK = Denmark, GB = Great Britain, NL = the Netherlands, D = Germany, F = France, GR = Greece, I = Italy, E = Spain

Fig. 2 Proportion of healthy Nordic food items (in %) consumed within standardized food groups by country* and gender: (a) females and (b) males; men and women aged 35–74 years, constituting a random sample of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) cohort. *N = Norway, S = Sweden, DK = Denmark, GB = Great Britain, NL = the Netherlands, D = Germany, F = France, GR = Greece, I = Italy, E = Spain

Table 2 Number and proportion of participants (%) consuming at or above the EPIC mean for the seven predefined ‘Nordic’ food items, by gender and country; men and women aged 35–74 years, constituting a random sample of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) cohort

N/A, not applicable.

Apples/pears

Apples and pears are consumed frequently in all participating countries; however, mean intake differs considerably, ranging from 47·5 g/d in Swedish men to 156·1 g/d in Italian men (Fig. 1(a)). A markedly higher consumption is found in Spain and Italy, compared with the other countries, especially driven by a high intake among men. The EPIC mean is 87·3 g/d for men and 80·8 g/d for women. With regard to percentage of total fruit intake, in both genders, this is one of the most stable food components across countries and centres (range: 23·0–31·1 % in women, 22·4–36·5 % in men), with no clear geographic gradient (Fig. 2).

Berries

The intake of berries varies considerably between countries, although not with a clear geographic gradient: mean intake is highest in Central Europe; among French, Germans and British participants (especially the health conscious) as well as Dutch women. Mean intake is lowest in Denmark and Greece (Fig. 1(b)). There is a large between-centre variation in Italy and Spain (see online supplementary material, Supplementary table s1). Women have a higher intake in all countries, except Denmark and Greece. The EPIC mean is 5·1 g/d for men and 8·5 g/d for women. When considering the percentage that berries contributes to total fruit intake, this is also highest for Central Europe: Germany, France (information available for women only), Great Britain and among Dutch women, but it is also high in Norway and Sweden (Fig. 2).

Cabbages

Cabbages are one of the food items that are consumed uniformly across the participating countries when considering mean intake (Fig. 1(c)). There is a tendency, though, of a higher intake in Central Europe: Germany, the Netherlands and Great Britain (especially in the health-conscious population), as well as among Norwegian women. Intake ranges from a mean of 10·3 g/d in Spanish men to 30·2 g/d in British women, compared with an EPIC mean of 17·2 g/d for men and 18·1 g/d for women. The percentage of total vegetable intake consumed as cabbages is also highest in Central Europe and lowest in Southern Europe. However, there is quite a large between-centre variation in Southern Europe (see online supplementary material, Supplementary table s1). There is no clear tendency towards a uniformly higher consumption among one gender over the other.

Root vegetables

Root vegetables show a geographic gradient, with a very low intake in Southern Europe and a high intake in Northern and Central Europe, except in the Netherlands (Fig. 1(d)). The EPIC mean intake is 14·8 g/d for men and 19·9 g/d for women. The contribution of root vegetables to total vegetable consumption resembles the mean intake, with the lowest percentage found in Southern Europe (3·6 % in Greek men, 4·5 % in Greek women) and the highest in Northern Europe, ranging from 12·1 % in Danish men to 19·9 % in Norwegian women. For all countries with data available for both genders, except the British, women consume a larger percentage of their total vegetables as root vegetables than men (Fig. 2).

Shellfish

Mean intake of shellfish is especially high in Spain, but also in France, Greece and Italy (primarily for men), albeit with some centre variation (see online supplementary material, Supplementary table s1). There is, however, no clear geographic trend in shellfish intake, with the lowest intakes found in the Netherlands, Germany and Great Britain, and an intermediate consumption in the Nordic countries (Fig. 1(e)). The EPIC mean intake is 4·4 g/d for men and 3·9 g/d for women. Shellfish constitutes a very small percentage of the total meat intake in Great Britain, the Netherlands and Germany, and the highest percentage in Greece and Spain. For all countries with data available for both genders, shellfish constitutes a larger percentage of the total meat intake for women than for men (Fig. 2).

Fish

Although fish is consumed in all countries, there is quite a large variation in mean intakes, with an exceptionally high intake in Spain, intakes closer to the EPIC mean (37·9 g/d in men, 27·9 g/d in women) in most other countries, and the lowest intake in Germany and the Netherlands (Fig. 1(f)). With regard to fish as a percentage of total meats consumed, the pattern is very similar, with the highest percentage in Spain (27·5 % in men, 28·7 % in women), a fairly similar percentage in the Northern European countries and Great Britain, France and Greece, and a very low percentage in Germany and the Netherlands.

Dark bread

The intake of dark bread varies substantially, with a more than tenfold variation in mean intake across countries: it is very low in Spain and Italy and highest in Denmark, Norway, Greece, the Netherlands and Germany (Fig. 1(g)). In contrast to berries, men tend to have a higher intake in almost all centres. The EPIC mean intake is 83·6 g/d for men and 60·7 g/d for women. Dark bread constitutes a very high percentage of total bread consumption in Greece (85·2 % in men, 81·8 % in women) as well as the Northern countries (range: 56·5–71·0 % in men, 60·7–82·8 % in women), the Netherlands (65·1 % in men, 74·3 % in women) and Germany (65·8 % in men, 69·8 % in women).

Overall pattern

A summary of the proportions of participants consuming at or above gender-specific EPIC means for all seven included dietary items is shown in Table 2, by country. The score has a possible range from 0 to 7, with no participants scoring 7 points. Table 2 shows no clear geographic gradient across countries, but a tendency towards a higher proportion of participants scoring high on several items in Denmark, Norway (data for women only) and also among English women, and a lower proportion of participants scoring 0 points in Norway and Denmark and among the Oxford health-conscious population, but a higher proportion of participants scoring 0 points in Italy and Sweden.

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to investigate the penetration of seven a priori defined healthy Nordic dietary items (apples/pears, berries, cabbages, dark bread, fish, shellfish and root vegetables) in the diet of ten European countries, in order to investigate if these were specifically related to a Nordic diet culture.

In our large study in ten European countries, we found a wide variation in intake of the included food items. However, for most food items, this variation did not follow a clear geographic gradient: intake of cabbages and berries was highest in Central Europe; intake of apples/pears was highest in Southern Europe; intake of dark bread was highest in Norway, Denmark and Greece; fish intake was highest in Southern as well as Northern countries; intake of shellfish was highest in Spain; and root vegetable intake was highest in Northern and Central European countries.

Thus the study results show that the included food items are not all typical for the Nordic countries, calling into question whether they should be considered specific Nordic dietary items. The dietary items most strongly related to the Nordic countries were dark bread, root vegetables and fish. However, none of these was exclusive to the Northern European countries, with a high consumption of dark bread also seen in Greece, of root vegetables also in Central Europe and of fish also in Southern Europe. For both fish and shellfish, there was a pattern with very low intakes in Germany and the Netherlands, which might be explained by the fact that these are the participating countries with the shortest coastlines and therefore they traditionally have low fish consumption.

In contrast to what could be expected, given the high profile of dark bread in Nordic gastronomy, the intake of dark bread was not highest here, but instead among Greek men, and it was also very high in Germany and the Netherlands. However, this may be due to a different type of ‘dark bread’ consumed across Europe: in the Nordic countries, this primarily refers to rye and coarse wholegrain bread, whereas elsewhere it primarily refers to bread with less wholegrain content. For instance, in the case of Greece, it primarily refers to consumption of ‘bread, wheat, brown’ (see online supplementary material, Supplementary table s2). Furthermore, the water content in dark bread may vary significantly across countries, which could explain some of the differences seen in intake between countries. As the 24HDR does not allow us to go into detail regarding the wholegrain content and types of grain, we can only speculate about this. In general, the question on ‘dark bread’ is made problematic by the fact that responders may not be aware whether they are consuming wholegrain bread or coloured white bread or white bread baked to a dark crust. This means that the question on ‘dark bread’ covers both baking method and water content, as well as wholegrain content. Also, all bread that is not 100 % white is classified as ‘dark’; meaning that bread with very low wholegrain content may be included. Given the poor validity of the dark bread questionnaire data as a proxy for wholegrain intake, one may instead turn to a biomarker of wholegrain intake; namely alkylresorcinols. These have been examined in 2845 EPIC participants from all ten countries. Findings suggest a higher wholegrain intake in Central and Northern Europe compared with the Mediterranean countries( Reference Kyrø, Olsen and Bueno-de-Mesquita 14 ), supporting our hypothesis that ‘dark bread’ may not necessarily include wholegrain bread only. In the Nordic EPIC countries, information about cereal consumption from the 24HDR has been reclassified and detailed information on type and amount of whole grains has been collected. A clear tendency was seen towards a higher intake of wholegrain products, especially wholegrain bread, in Denmark and Norway compared with Sweden whereas the total rye intake was highest in Denmark and Sweden compared with Norway( Reference Kyrø, Skeie and Dragsted 15 ), suggesting inter-Nordic variation in food habits. This is also reflected in the present study: when comparing the Nordic countries, Swedes seem to present a somewhat different intake of the included items compared with Danes and Norwegians, who have a more similar intake, suggesting that the selected dietary components are more representative of these two countries than of the Swedish diet. This could be due to a stronger Swedish tradition for hot lunches, compared with a stronger tradition for sandwiches in Denmark and Norway.

The present study is based on an a priori approach, including beforehand defined, healthy dietary items. Previously, an a posteriori, data-driven approach has been used to identify dietary items associated with each country in EPIC( Reference Slimani, Fahey and Welch 2 ), using the specific data at hand as a basis for statistical modelling of associations( Reference Trichopoulos and Lagiou 16 ). The food items found related to the Nordic countries in the a posteriori approach were almost exclusively items considered harmful in relation to health (e.g. alcohol, soft drinks and processed meat), so that study did not inform on any potential strategies for improving health through local dietary components( Reference Slimani, Fahey and Welch 2 ). The advantages of our a priori approach is that it identifies not just all food items associated with a country, but specifically maps consumption of likely health-enhancing food items, suggesting entry points for preventive initiatives through dietary modification. The weaknesses of the a priori approach include consideration only of food items defined beforehand, when other food items could possibly also be considered part of a health-enhancing Nordic diet.

There is some discrepancy between the included dietary components in this and previous studies on a healthy Nordic dietary pattern, which have included e.g. rapeseed oil, low-fat dairy products, wild and pasture-fed land-based animals, potatoes, oats and barley( Reference Bere and Brug 4 – Reference Kyro, Skeie and Loft 6 , Reference Uusitupa, Hermansen and Savolainen 8 , Reference Adamsson, Reumark and Cederholm 17 , Reference Mithril, Dragsted and Meyer 18 ).

The a priori selection of dietary items in the present study was based on the criteria mentioned in the introduction, as well as the availability of data in the EPIC cohort. Potatoes and low-fat dairy products were thus not included because their health-beneficial effects are not equivocal, whereas for the remaining dietary items, we did not have data on these in the 24HDR in all participating countries and were therefore not able to include them.

The use of composite dietary pattern indices in nutritional epidemiology is gaining ground, with the Mediterranean dietary score, defined by high intake of fruits and vegetables, legumes, grains, olive oil and fish, low intakes of meat and poultry and moderate alcohol consumption( Reference Willett, Sacks and Trichopoulou 19 ), as the forerunner. This pattern has also been proved beneficial outside its traditional geographic regions, including in the Nordic countries( Reference Osler and Schroll 20 , Reference Lagiou, Trichopoulos and Sandin 21 ). However, adherence to this dietary pattern has been hard to implement in Nordic countries( Reference da Silva, Bach-Faig and Raido 9 ), suggesting that future dietary campaigns may better focus on regional, healthy dietary items. Our study has shown that some components of the Mediterranean dietary score, such as fish and grains (here equivalent to dark bread consumption), are also part of a Nordic dietary pattern. However, the foods consumed probably refer to different variants, e.g. different fish varieties and dark wheat bread instead of rye bread. But the a priori defined Nordic dietary components investigated in our study also show higher consumption in European regions other than the Nordic: Central European countries had a high intake of berries, cabbages and root vegetables and Southern European countries of apples/pears and shellfish. This suggests that the definition of a health-promoting dietary pattern is possible in each European region or country, taking its starting point in regional, familiar items, which could be used in national health campaigns( Reference Mithril, Dragsted and Meyer 18 ). Recently, for instance, a Baltic Sea diet has been suggested( Reference Kanerva, Kaartinen and Schwab 22 ). These regional diets thus seem primarily defined by their ability to be grown locally, strengthening sustainability, rather than their geographical exclusiveness.

The strengths of the present study include the large study base including ten European countries and spanning a wide variety of dietary and lifestyle habits, making it well suited to investigate diet across geographic regions in Europe. Participants are included from as far north as northern Norway to as far south as southern Italy. Furthermore, the data presented here were derived from a standardized 24HDR, based on uniform food composition databases, which reduces the possibility of distortion of observed mean intakes( Reference Slimani, Deharveng and Unwin 23 ). The 24HDR was developed specifically for this population. It was administered to a sub-sample of participants selected with the purpose of not only being representative of the entire EPIC cohort with regard to sociodemographic and lifestyle factors but also in relation to coverage of days of the week and seasons of the year, where food habits may differ( Reference Slimani, Kaaks and Ferrari 11 ). The 24HDR has the advantage that it is less subject to measurement error as it is easier to remember foods consumed in the last 24 h compared with an FFQ, which usually asks about intake over a longer period of time. Finally, the analyses were weighted by day and season of data collection in order to correct for discrepancies in these between centres, as there may be a rather large variation with e.g. season (most likely especially for berries, which is a more seasonally consumed food item). It is possible that this weighting has not completely eliminated day and seasonal variation between centres, but it should have removed most of it.

A limitation of the study was that we only had a single 24HDR measurement per study subject, which limited the accuracy in estimation of intakes of individuals, but does not affect estimation of population means at an aggregate level, which was the main objective of our study. However, the 24HDR was not administered especially with the focus of the present study in mind, leaving deficiencies in the estimation of some dietary components; especially dark bread, but other included components may also suffer from imprecision due to less optimal food grouping or coding. Furthermore, the dietary data in the study were collected between 1995 and 2000( Reference Slimani, Kaaks and Ferrari 11 ). It is possible that the dietary patterns of the participating countries have changed during the last 10–15 years( Reference Rumm-Kreuter 24 ). Finally, the EPIC study is not designed to be representative of the general population in the countries from which participants derive, as they are sampled by convenience and voluntarism rather than representativeness, and consequently generalization of the results to the general population in the same age group should only be done with caution( Reference Riboli, Hunt and Slimani 10 ). Unfortunately, no French or Norwegian men were invited to participate, leaving us unable to investigate gender-specific diet in these countries. For most countries, there seems to be some variation between male and female intakes of the selected food items. This could be related to the differences in overall energy intake between sexes, but does not appear to be the explanation when considering the percentage of total food group consumption (Fig. 2).

Conclusion

In conclusion, the results of the present study indicate that components of a healthy Nordic diet are consumed all over Europe, just as the Mediterranean dietary score is not composed of items exclusively consumed in the Mediterranean countries, but rather those characterizing the dietary pattern of the Mediterranean area( Reference Bere and Brug 25 ). Some health-promoting dietary foods are, however, more closely related to a Nordic dietary pattern; this seems especially to be the case for dark bread and root vegetables – primarily driven by a large Danish and Norwegian consumption. Fish seems to be an inherent part of the Mediterranean as well as the Nordic diet. There is scope to further promote these regionally familiar dietary items in future health-promoting campaigns in the Nordic countries as well as outside them, as cabbages, apples/pears, berries and shellfish also seem to be common in different European regions.

Acknowledgements

Sources of funding: This work was carried out as a part of the research programme Gene–Diet Interactions in Obesity (GENDINOB). GENDINOB is supported by the Danish Council for Strategic Research (grant no. 09-067111). The work is part of the activities in the Danish Obesity Research Centre (DanORC, see www.danorc.dk). It was supported by the NordForsk Nordic Centre of Excellence (NCoE) programme Systems Biology in Controlled Dietary Interventions and Cohort Studies – SYSDIET (project no. 070014) and HELGA (project no. 070015). The coordination of EPIC is financially supported by the European Commission (DGSANCO) and the International Agency for Research on Cancer. The national cohorts are supported by: Danish Cancer Society (Denmark); Ligue Contre le Cancer, Institut Gustave Roussy, Mutuelle Générale de l'Education Nationale and Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM; France); Deutsche Krebshilfe, Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum and Federal Ministry of Education and Research (Germany); Ministry of Health and Social Solidarity, Stavros Niarchos Foundation and Hellenic Health Foundation (Greece); Italian Association for Research on Cancer (AIRC) and National Research Council (Italy); Dutch Ministry of Public Health, Welfare and Sports (VWS), Netherlands Cancer Registry (NKR), LK Research Funds, Dutch Prevention Funds, Dutch ZON (Zorg Onderzoek Nederland), World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF) and Statistics Netherlands (the Netherlands); ERC-2009-AdG 232997 and Nordforsk, Nordic Centre of Excellence programme on Food, Nutrition and Health (Norway); Health Research Fund (FIS), the Regional Governments of Andalucía, Asturias, Basque Country, Murcia and Navarra, and ISCIII RETIC (RD06/0020; Spain); Swedish Cancer Society, Swedish Scientific Council and Regional Government of Skåne and Västerbotten (Sweden); Cancer Research UK, Medical Research Council, Stroke Association, British Heart Foundation, Department of Health, Food Standards Agency and Wellcome Trust (Great Britain). The above-mentioned funders had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflicts of interest: None declared. Ethical considerations: The EPIC study was approved by the Ethical Review Board of the International Agency for Research on Cancer and the Institutional Review Board of each participating EPIC centre. Contributions of each author: Literature search: N.R. Figures: N.R. and J.C. Study design: N.R., A.O. and A.Tj. Data collection: E.R. and A.Tj. Data analysis: N.R., K.B. and J.C. Data interpretation: N.R., A.O., J.H., T.I.A.S., C.C.D., K.O., F.C.-C., M.C.B.-R., V.C., B.T., R.K., H.B., A.v.R., A.Tr., E.O., E.V., V.P., C.S., A.M., G.M., P.H.M.P, H.B.B.d.M., D.E., G.S., L.A.Å., P.A., P.J., E.A., J.M.H., J.R.Q., E.M.-M., L.M.N., I.J., E.W., I.D., A.A.M., K.T.K., D.R., A.-C.V., T.K., E.R. and A.Tj. Writing of manuscript: N.R., A.O., K.B., J.C., J.H., T.I.A.S., C.C.D., K.O., F.C.-C., M.C.B.-R., V.C., B.T., R.K., H.B., A.v.R., A.Tr., E.O., E.V., V.P., C.S., A.M., G.M., P.H.M.P., H.B.B.d.M., D.E., G.S., L.A.Å., P.A., P.J., E.A., J.M.H., J.R.Q, E.M.-M., L.M.N., I.J., E.W., I.D., A.A.M., K.T.K., D.R., A.-C.V., T.K., E.R. and A.Tj. All authors approved the final version of this paper.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1368980014000159