Impact statement

As the water–energy–food (WEF) nexus approach grows and expands, there is a need to apply the nexus to implement technical solutions, resource management, and policy development. Previous studies have comprehensively discussed WEF nexus tools (frameworks, discourses and models) without linking them to applications. This review focused on WEF nexus applications to identify how WEF nexus tools have been applied to facilitate knowledge generation and decision-making in the Global South and some opportunities and challenges arising from these efforts. The review synthesised valuable information on how the nexus tools can generate more knowledge on resource utilisation, especially in constrained environments. Optimistic opportunities for applying nexus approaches to solve real problems and inform policy decisions are provided. The review also reveals that WEF nexus approaches are wider than water, energy and food. There are possibilities of extending to address other global challenges such as climate change, environmental (and ecosystem) degradation, land scarcity, human health, and livelihoods. While there are concerns about data scarcity and scale mismatch when applying nexus methodologies in solving problems, we identify studies that have overcome these hurdles with acceptable results. The review will be of value to scientists and practitioners as it outlines recommendations towards operationalising the WEF nexus approach.

Introduction

It has been over a decade since the accentuation of the water–energy–food (WEF) nexus at the 2011 Bonn Nexus Conference on the Water, Energy and Food Security Nexus – Solutions for the Green Economy (Hoff, Reference Hoff2011). Driving the WEF nexus is a holistic vision of sustainability that seeks to strike a balance among key strategic resources (water, energy, and food), the different goals, interests, and needs of people and the environment in a world faced with population growth, urbanisation, industrialisation, resource depletion, climate change and degrading ecosystem services (Hoff, Reference Hoff2011). Traditional and sector-based research approaches fall short of addressing the linkages among water, energy, and food resources systems, given that decisions taken in one sector can spill over and affect the other sectors (Bazilian et al., Reference Bazilian, Rogner, Howells, Hermann, Arent, Gielen, Steduto, Mueller, Komor, Tol and Yumkella2011; Lawford, Reference Lawford2019). Nexus approaches facilitate the evaluation of synergies and trade-offs holistically to avoid conflicts, optimise resource allocation, minimise risk on investment and maximise economic returns (Fan, Reference Fan2016; Mohtar and Lawford, Reference Mohtar and Lawford2016; Mohtar and Daher, Reference Mohtar and Daher2017; Cai et al., Reference Cai, Wallington, Shafiee-Jood and Marston2018). Since its inception, the WEF nexus approach sparked interest among the academic and development communities, resulting in policy dialogues and the development of a wide range of frameworks and tools for analysing the WEF nexus to guide decision-making for improved governance across sectors (Klümper and Theesfeld, Reference Klümper and Theesfeld2017; Ramaswami et al., Reference Ramaswami, Boyer, Nagpure, Fang, Bogra, Bakshi, Cohen and Rao-Ghorpade2017; McGrane et al., Reference McGrane, Acuto, Artioli, Chen, Comber, Cottee, Farr‐Wharton, Green, Helfgott and Larcom2019; Simpson and Jewitt, Reference Simpson and Jewitt2019).

Significant progress has been made in developing WEF nexus tools for different spatial and temporal scales, contexts and users. The abilities, strengths, and shortcomings of current techniques in capturing the nexus approach and its different components have been the subject of several reviews (Kaddoura and el Khatib, Reference Kaddoura and el Khatib2017; Dai et al., Reference Dai, Wu, Han, Weinberg, Xie, Wu, Song, Jia, Xue and Yang2018; Shannak et al., Reference Shannak, Mabrey and Vittorio2018; McGrane et al., Reference McGrane, Acuto, Artioli, Chen, Comber, Cottee, Farr‐Wharton, Green, Helfgott and Larcom2019; Endo et al., Reference Endo, Yamada, Miyashita, Sugimoto, Ishii, Nishijima, Fujii, Kato, Hamamoto, Kimura, Kumazawa and Qi2020; Purwanto et al., Reference Purwanto, Sušnik, Suryadi and de Fraiture2021). Some of the weaknesses identified with the WEF nexus was the omission of other important sectors that influence resource security, such as land, ecosystems and climate change (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Campana, Yao, Zhang, Lundblad, Melton and Yan2018; Dalla Fontana and Boas, Reference Dalla Fontana and Boas2019; Bian and Liu, Reference Bian and Liu2021). Taguta et al. (Reference Taguta, Senzanje, Kiala, Malota and Mabhaudhi2022) reported the lack of basic and requisite characteristics in documented WEF nexus tools, including ready availability, geospatial analytic capabilities, and applicability across different scales and locations. The lack of data that supports efforts to understand system boundaries and spatial dimensions was also cited as a barrier to the application of the WEF nexus approach (McCarl et al., Reference McCarl, Yang, Schwabe, Engel, Mondal, Ringler and Pistikopoulos2017a; Reference McCarl, Yang, Srinivasan, Pistikopoulos and Mohtar2017b; Gomo et al., Reference Gomo, Macleod, Rowan, Yeluripati and Topp2018; Lawford, Reference Lawford2019). Additionally, WEF nexus methodologies often fail to reflect the study region’s uniqueness and to incorporate appropriate activities among different contexts (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Campana, Yao, Zhang, Lundblad, Melton and Yan2018; Dalla Fontana and Boas, Reference Dalla Fontana and Boas2019; Bian and Liu, Reference Bian and Liu2021). For example, the Global South and Global North have differing development trajectories, thus unique priorities and activities pursuing water, energy and food resource security (Reidpath and Allotey, Reference Reidpath and Allotey2019; Kowalski, Reference Kowalski, Leal Filho, Azul, Brandli, Lange Salvia, Özuyar and Wall2020).

As the nexus approach grows and expands, there has been rising interest to shift from theory to practice, thus applying the nexus for implementing technical solutions, resource management and policy development (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Yang, Cudennec, Gain, Hoff, Lawford, Qi, de Strasser, Yillia and Zheng2017; Purwanto et al., Reference Purwanto, Sušnik, Suryadi and de Fraiture2021). Previous studies have discussed WEF nexus tools (frameworks, discourses and models) comprehensively without linking them to applications (Kaddoura and el Khatib, Reference Kaddoura and el Khatib2017; Dai et al., Reference Dai, Wu, Han, Weinberg, Xie, Wu, Song, Jia, Xue and Yang2018; Shannak et al., Reference Shannak, Mabrey and Vittorio2018; McGrane et al., Reference McGrane, Acuto, Artioli, Chen, Comber, Cottee, Farr‐Wharton, Green, Helfgott and Larcom2019; Endo et al., Reference Endo, Yamada, Miyashita, Sugimoto, Ishii, Nishijima, Fujii, Kato, Hamamoto, Kimura, Kumazawa and Qi2020; Purwanto et al., Reference Purwanto, Sušnik, Suryadi and de Fraiture2021). This study focuses on WEF nexus applications within the Global South as the region is associated with high levels of poverty, high population growth rates and a high prevalence of food insecurity, among other issues (Akinbode et al., Reference Akinbode, Okuneye and Onyeukwu2022; Fuseini et al., Reference Fuseini, Enu-Kwesi, Abdulai, Sulemana, Aasoglenang and Domapielle2024). The specific objectives are to (i) identify how WEF nexus tools have been applied to facilitate knowledge generation and decision-making in the Global South, (ii) identify nexus nodes (units of the nexus structure) being considered under different contexts in the Global South, (iii) identify limitations in the application of WEF nexus tools for decision making and knowledge generation in the Global South and iv) propose pathways for operationalising the WEF nexus that are contextualised for the Southern African Development Community (SADC) region.

The paper is structured as follows: after this introduction, ‘Materials and methods’ section describes the method and materials used, including data sources, data curation, and analysis of the data. ‘Results and discussion’ section presents the results: (i) a synopsis of the database, (ii) how WEF nexus tools have been applied for knowledge generation and decision support, and (iii) challenges associated with WEF nexus applications in the Global South. ‘Way forward and recommendations: Pathways towards operationalising the WEF nexus in Southern Africa’ section provides plausible pathways for operationalising the WEF nexus. ‘Study limitations’ section highlights the study’s limitations, and ‘Conclusions’ section is the study’s conclusion.

Materials and methods

Definition of terms

In this study, application refers to the published use of the WEF nexus (concept, discourse, model, etc.) in assessing real-life circumstances or status quo assessment or simulating and modelling hypothetical scenarios (Saundry and Ruddell, Reference Saundry and Ruddell2020). The WEF nexus can serve multiple roles, such as a conceptual framework, an analytical tool, or a discourse (Keskinen et al., Reference Keskinen, Guillaume, Kattelus, Porkka, Räsänen and Varis2016). Firstly, the WEF nexus conceptual framework leverages an understanding of WEF linkages to promote coherence in policy-making and enhance sustainability. Secondly, WEF nexus analytics systematically use quantitative tools (e.g. quantitative models) and/or qualitative methods (e.g. participatory stakeholder workshops) to highlight and understand interactions among water, energy, and food systems. Thirdly, the nexus discourse can facilitate problem-framing and promote cross-sectoral collaboration (Keskinen et al., Reference Keskinen, Guillaume, Kattelus, Porkka, Räsänen and Varis2016; Albrecht et al., Reference Albrecht, Crootof and Scott2018).

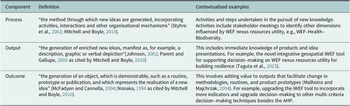

One of the study objectives was to identify the extent to which the WEF nexus was used to generate knowledge and make decisions. According to the Oxford Dictionary, knowledge is “facts and skills acquired through experience or learning; the theoretical or practical understanding of a subject matter”. For context, this study applied the definition to assess and map the application of WEF nexus tools, frameworks and discourse to generate facts and tools that inform the better management of WEF nexus resources. This study targeted the whole knowledge generation value chain, i.e., knowledge generation as a process, output, and outcome in the WEF nexus theatre of activity (Mitchell and Boyle, Reference Mitchell and Boyle2010). Each value chain component is defined in Table 1.

Table 1. Knowledge generation value chain, i.e. process, output and outcome

The study also defined decision-making as situations whereby stakeholders are individually or collectively required to make choices based on the available facts or information (Hill and McShane, Reference Hill and McShane2008). The decision-making process can be a bottom-up or top-down approach.

Search strategy

The review was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) protocol (Moher et al., Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman and Group2009; Page et al., Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann, Mulrow, Shamseer, Tetzlaff, Akl, Brennan, Chou, Glanville, Grimshaw, Hróbjartsson, Lalu, Li, Loder, Mayo-Wilson, McDonald, McGuinness, Stewart, Thomas, Tricco, Welch, Whiting and Moher2021) (SF1). The Population, Intervention, Comparison and Outcomes (PICO) framework was used to develop literature search strategies to ensure comprehensive and bias-free searches (Table 2).

Table 2. PICO strategy used to develop the search strategy

A literature search was conducted in two databases [Scopus and Web of Science Core Collection (WoS)] (The last search was on 02 April 2024). The search criteria in the two databases (Scopus and WoS) are presented in Table 3. In the WoS platform, we searched all editions of the WoS core collection.

Table 3. Terms used in searching literature in Scopus and WoS databases

Literature from the Global South was screened during abstract screening. The classification of studies between Global North and Global South was based on Dados and Connell (Reference Dados and Connell2012), the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (2018) and Kowalski (Reference Kowalski, Leal Filho, Azul, Brandli, Lange Salvia, Özuyar and Wall2020). The search identified 1,451 and 921 articles from Scopus and WOS, respectively. Together, the initial database comprised N = 2,372 articles. A duplicate check in MS Excel identified 703 duplicates that were immediately removed. Consequently, 1,699 articles were screened by title and abstract (Supplementary Figure [SF] 1). Consideration was given to peer-reviewed papers (articles), scientific book chapters, papers and proceedings written and published in English. The date of publication was limited to 2011 (birth of WEF nexus) to the date of the last search (02 April 2024), while the geographic scope, journal disciplines and impact factors were kept open to capture all WEF nexus case studies.

Screening and bias reporting

Three authors (T.P.C., C.T. and T.L.D.) were assigned to screen the abstracts independently. The screening was done by scoring an article’s relevance against a five-point Likert scale (1 – extremely irrelevant and 5 – denoting very relevant). The Koutsos et al. (Reference Koutsos, Menexes and Dordas2019) criteria for ranking article relevance was modified to develop scoring criteria for the articles and facilitate screening (Table 4). Articles that were scored 3 and above by all authors were automatically included. Articles scored 3 or above by at least two authors were also automatically included. Where only one author scored 3 or above, it was resolved by discussion. Articles that were scored 2 and below by all authors were excluded. Articles reporting WEF nexus applications from the Global North were scored 1 as they were extremely irrelevant for this review. Secondary articles, such as reviews, were also scored 1 as they summarised existing studies, and this study delved into primary research (Table 4). The screening favoured publications capturing any nexus and applying WEF nexus concepts, discourse and tools in addressing real-life situations from the Global South. Of the 1,699 articles, 815 were from the Global North, while 127 were reviews and other secondary articles. The remaining 757 articles included 336 studies that applied the WEF nexus approach for any reason (to gain insights, solve a problem, plan, identify factors and aid in decision-making.). These 336 studies were subjected to data extraction by one author (T.P.C.).

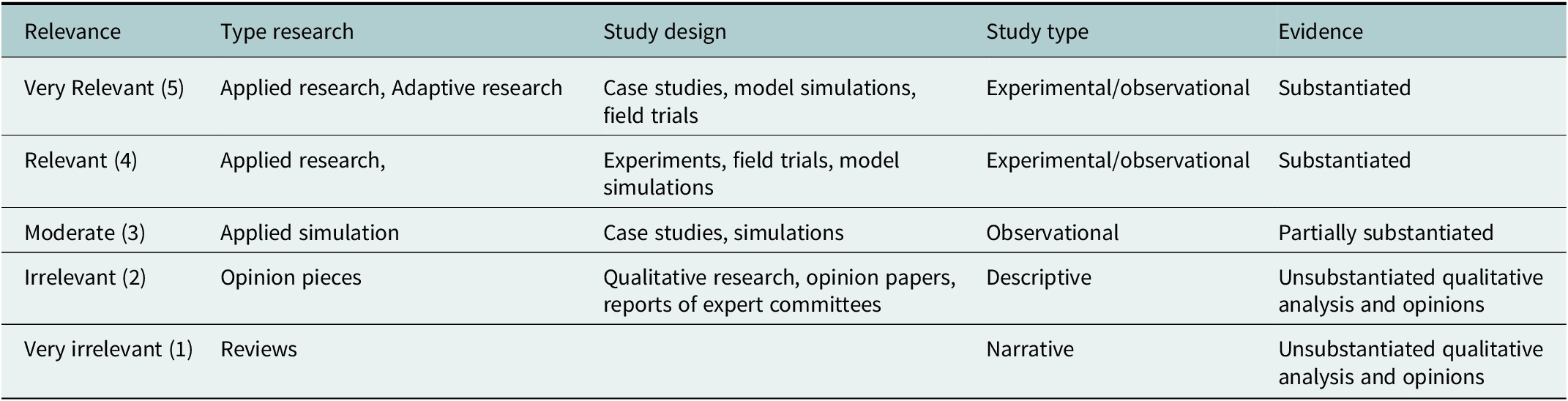

Table 4. Manuscript scoring based on the study’s relevance (modified from Koutsos et al., Reference Koutsos, Menexes and Dordas2019)

Data collection

A data extraction sheet was designed in MS Excel. Key data on the selected papers were extracted from the eligible studies and organised in the data extraction sheet. The data items were organised in columns, including publication details (author, year, title), objective, case study (location, country, continent, region), scale (spatial, temporal), nexus nodes, involvement of stakeholders and analytical or modelling tool used. The World Bank regional units (Africa, South Asia, Middle East, Latin America and the Caribbean, Central Asia, and East Asia) were used to categorise regions. The spatial scales were classified as household, field, farm, community, village, town, city, municipality, district, metropolitan, provincial, national, catchment, watershed, river basin, aquifer, continent, and global. Where studies explicitly highlighted the limitations of the application, this was captured.

Data items and analysis of studies

To facilitate data visualisation and trend analysis, Bibliometrix and Biblioshiny packages from the R language environment were used to map research hotspots and to develop an international collaboration network map. The temporal two-dimensional multi-correspondence analysis (MCA) plot was used to visualise the WEF nexus case studies approach from 2011–2024. A trend analysis was done based on abstracts and keywords. The word tree was prepared using Jason Davies’ Word Tree (Wattenberg and Viégas, Reference Wattenberg and Viégas2008).

Results and discussion

Overview of WEF nexus application studies in the Global South

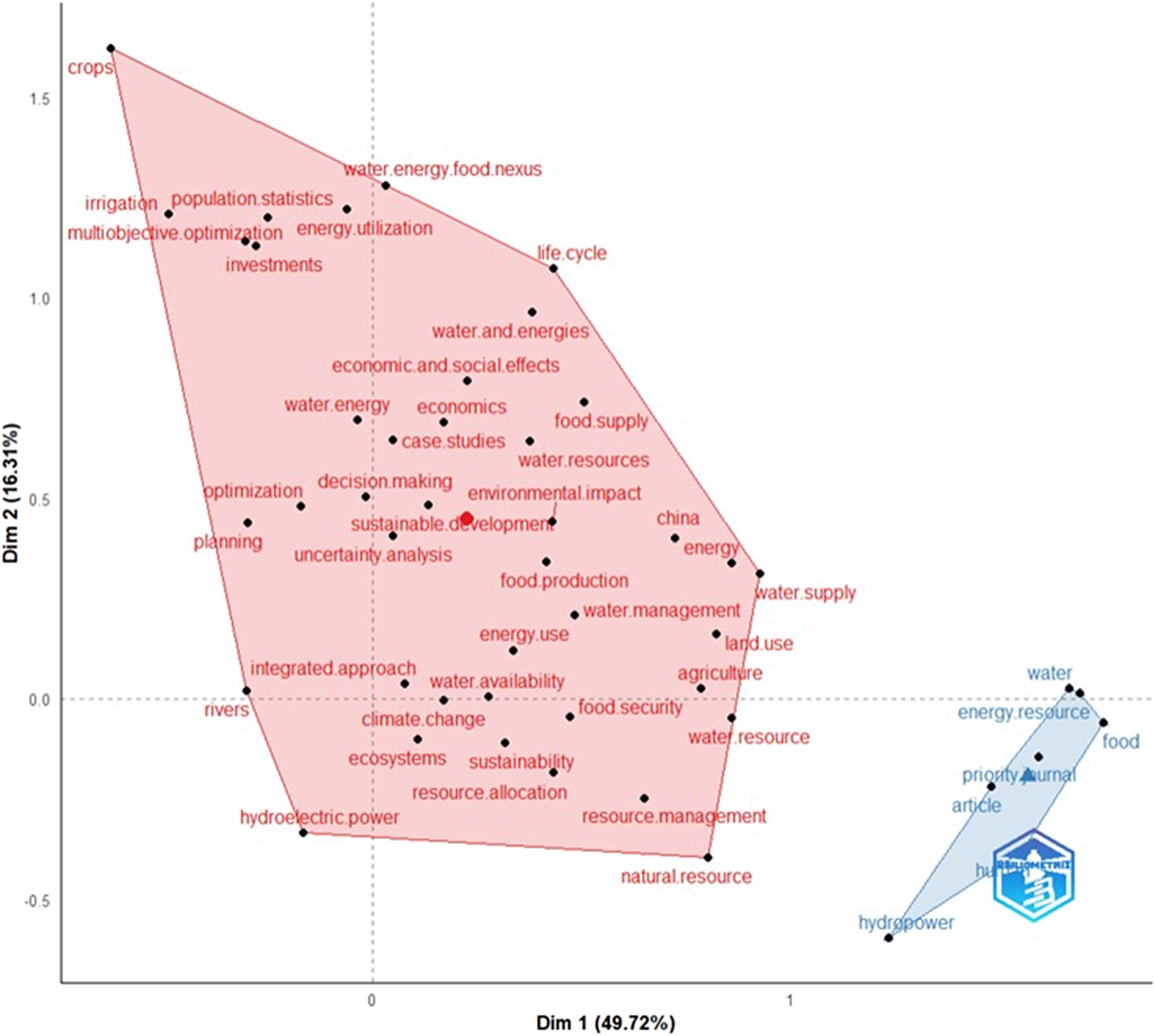

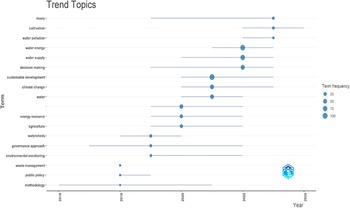

The conceptual structure map showed that the best size reduction between the two dimensions accounted for 66% of the total variability, i.e., 49.72% and 16.31% for dimensions 1 and 2, respectively (Figure 1). The conceptual structure map showed two distinct clusters (red and blue), and in the plot, the closer the points are to each other, the more similar subject matters they cover in their respective sectors. For example, the sectors Dim 2 (0.0–1.5) and Dim 1 (origin-0) with n= 12 words show a close relationship amongst the words water–energy, irrigation, crops, investments, optimization and energy utilisation, to mention a few. In this context, we observed that, to a greater degree, several cases were linked to economics, economic and social effects, water resources and food supply (Figure 1). China is the only country that appeared in the keyword mapping (Figures 1 and 3), implying that the database comprises many studies conducted in China compared to other countries. An earlier review (Correa-Porcel et al., Reference Correa-Porcel, Piedra-Muñoz and Galdeano-Gómez2021) and a recent one (Rhouma et al., Reference Rhouma, El Jeitany, Mohtar and Gil2024) reported that China ranks second to the USA regarding the total number of WEF nexus articles published in each country. This could be because China’s GDP has been increasing by 9% annually, making it the fastest-growing economy in the Global South (https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/china/overview).

Figure 1. Temporal two-dimensional visual showing the red and blue cluster grouping words according to WEF nexus associations with case studies that applied the WEF nexus approach to create knowledge or for decision support. The red cluster (n = 39 words) had higher word association than the blue cluster (n = 6 words).

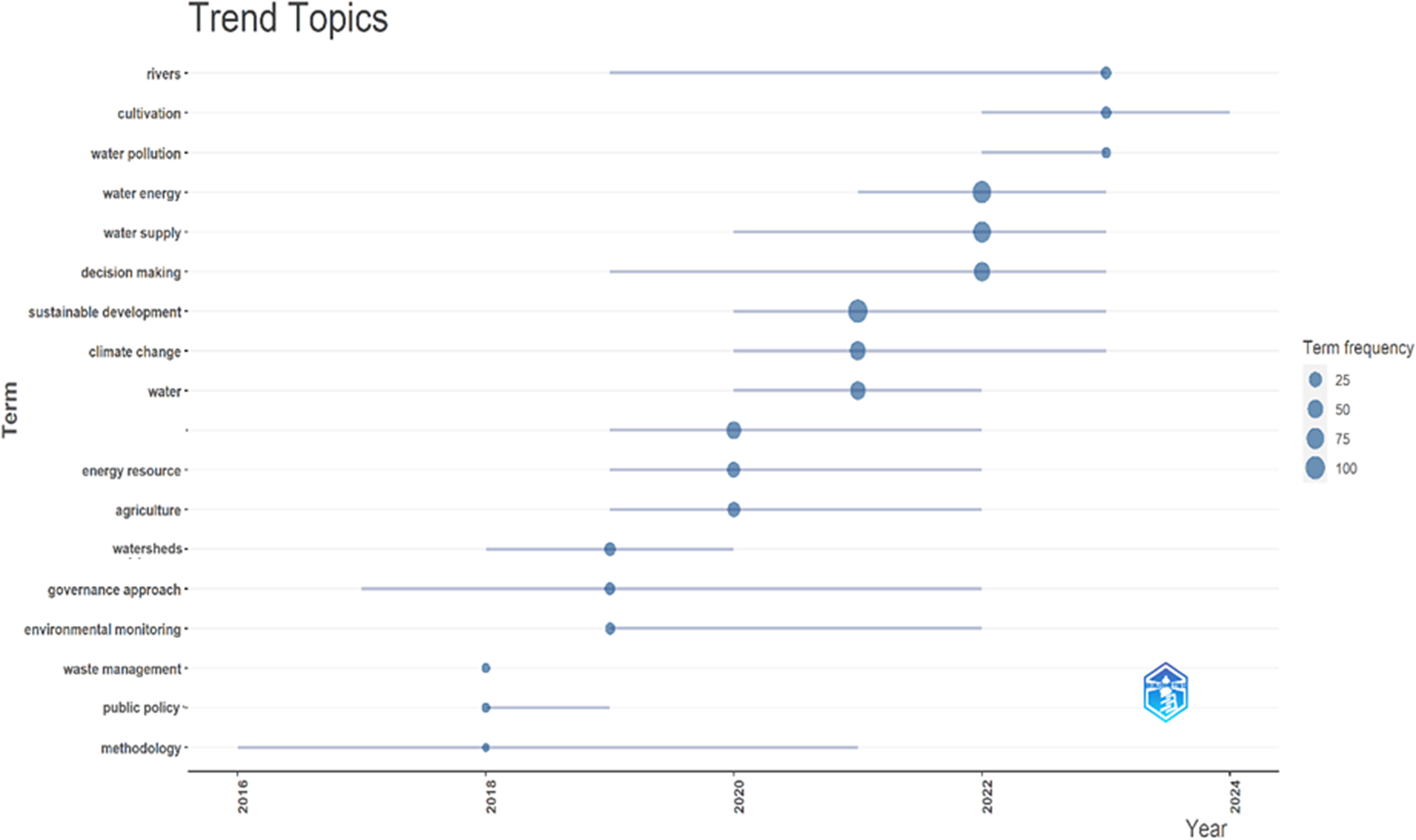

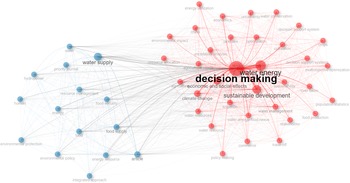

Trend analysis gave an insight into trending topics based on word occurrence (Figure 2). Between 2020 and 2022, sustainable development and the WEF nexus resources dominated the discourse. This could mean that the WEF nexus is integral in the quest for integrative sustainable management of resources and economic development. A key WEF nexus challenge is to develop policies that support the sustainability of water, energy, and food resources while ensuring universal access to these resources (Simpson and Jewitt, Reference Simpson and Jewitt2019). Post 2022, the relatively dominant words included rivers, cultivation, and water pollution were dominant; this is potentially attributed to river basins being good examples where water, energy, and food interconnect as they supply freshwater, regulate water flow and quality, and generate energy (such as hydropower) (Ringler et al., Reference Ringler, Mondal, Paulos, Mirzabaev, Breisinger, Wiebelt, Siddig, Villamor, Zhu and Bryan2018). The word methodology was prominent post-2016–2016, which we assume could be attributed to the development of WEF nexus tools. The evolution of the WEF nexus as an integrative approach gained traction post-2016. After 2018, the term decision making became more prominent.

Figure 2. Trend topics associated with the WEF Nexus applications database. The trend diagram depicts the evolution of different subject matters related to the WEF nexus research frontier. After the year 2022, decision-making dominated the WEF nexus space. Decision-making is part of the knowledge generation value chain, i.e. process, outcome and output.

Application of nexus approaches

From the databases, we categorised the overall purpose of nexus applications. Two major themes were used: (i) to improve understanding and generate knowledge on WEF interactions and (ii) as a decision support tool.

Understanding and knowledge generation of WEF nexus interactions

Studies under this category aimed to generate knowledge on nexus interactions by quantifying WEF indices at varying scales and understanding the impact of resource allocation at different scales. This knowledge generation approach was mainly focused on the outcomes and outputs components of the knowledge generation value chain. These studies are important to facilitate adopting the approach through evidence on quantitative and qualitative relationships among the sectors and highlighting the advantages of nexus vs silo approaches (Naidoo et al., Reference Naidoo, Nhamo, Mpandeli, Sobratee, Senzanje, Liphadzi, Slotow, Jacobson, Modi and Mabhaudhi2021). Most of the studies in the database (N = 185) were under this category, which could be explained by the fact that the nexus research is shifting from theory to practice. Most studies have been focused on testing and validating the ability of nexus tools to capture intersectoral linkages, thus offering practical recommendations for their application as decision-support tools or to address specific challenges (Supplementary Table [ST] 1).

Taghdisian et al. (Reference Taghdisian, Bukkens and Giampietro2022) explored the potential of the ‘Multi-Scale Integrated Analysis of Societal and Ecosystem Metabolism’ (MuSIASEM) framework for resource analysis at the river basin scale. Their results showed that the framework would fill an important gap to guide nexus governance in the region; however, there was a need to co-produce analysis with social actors, and there was a need for good-quality basin data. Stein et al. (Reference Stein, Pahl-Wostl and Barron2018) analysed how actors involved in the governance of WEF are embedded in social networks. They highlighted that actors are not simply disconnected, but there are hierarchical structures that result in coordination challenges despite visible theoretical cross-sectorial linkages. By combining different methods (gridded water balance model and GIS), Daccache et al. (Reference Daccache, Ciurana, Diaz and Knox2014) quantified irrigated regions’ water demand and energy footprint. The study demonstrated the possibility of combining different methods to integratively analyse the WEF nexus and facilitate an understanding of the water, energy, and food nexus that could be used for policy formulation on irrigated agriculture (Daccache et al., Reference Daccache, Ciurana, Diaz and Knox2014). Another knowledge generation as an output scenario was done by Taguta et al. (Reference Taguta, Nhamo, Kiala, Bangira, Dirwai, Senzanje, Makurira, Jewitt, Mpandeli and Mabhaudhi2023). The authors (Taguta et al., Reference Taguta, Nhamo, Kiala, Bangira, Dirwai, Senzanje, Makurira, Jewitt, Mpandeli and Mabhaudhi2023) developed a geospatial integrative iWEF 1.0 model to assess WEF nexus usage across multiple scales for building resilience and adaptation strategies.

Planning and decision support

Planning is concerned with setting objectives and targets and formulating plans to accomplish the objectives. It involves logical thinking and rational decision-making. Nexus tools have been applied to evaluate options and scenarios for the identification of optimal decisions for resource allocation at different scales and contexts. The modified search strategy incorporating WEF nexus and decision-making produced a co-occurrence network in which decision-making was strongly linked to water supply, economic and social effects, multiple objective optimisation, population, policy making, and energy utilisation, to mention a few (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Decision-making linkages co-occurrence network. The main red cluster had decision-making at the centre and was effectively and directly linked to 32 socio-economic, socio-political-ecological related words. The minor blue cluster centred on water supply was linked with decision-making for food supply, hydropower, and environmental protection, to mention a few.

In addition to optimal resource allocation, nexus approaches have also been valuable in identifying the most economical strategies, such as energy utilisation, water management, water conservation, and resource allocation, to mention a few (Seeliger et al., Reference Seeliger, de Clercq, Hoffmann, Cullis, Horn and de Witt2018; Das et al., Reference Das, Sahoo and Panda2020; Siderius et al., Reference Siderius, Biemans, Kashaigili and Conway2022). The authors hypothesise that the application was based on the ability of the WEF nexus to identify trade-offs and synergies that facilitate decision-making at the operational and policy levels. An example of a nexus approach for planning purposes was when the future allocation of land and water resources for agriculture and hydropower generation in the transboundary upper Blue Nile (UBN) basin was determined using a WEF nexus framework by Allam and Eltahir (Reference Allam and Eltahir2019). Li et al. (Reference Li, Li, Fu, Liu, Yu and Li2021a) applied the WEF nexus approach at the field scale to identify a sustainable cropping system to maximise crop production while reducing energy consumption and water depletion. Also, under agricultural development, Guo et al. (Reference Guo, Zhang, Engel, Wang, Guo and Li2022) applied a nexus approach to determine sustainable agricultural irrigation development at the river basin scale without negatively affecting hydropower generation and other water uses. In another study, a nexus tool was used to identify stakeholders that would participate in a programme to rehabilitate a reservoir (Melloni et al., Reference Melloni, Turetta, Bonatti and Sieber2020). In the context of decision support, the nexus that included climate as an important node was applied to identify adaptation strategies and to ensure the resilience of current WEF policies to climate change (Mabhaudhi et al., Reference Mabhaudhi, Nhamo, Mpandeli, Nhemachena, Senzanje, Sobratee, Chivenge, Slotow, Naidoo, Liphadzi and Modi2019; Qi et al., Reference Qi, Li, Yuan and Wang2021; Yue et al., Reference Yue, Wu, Wang and Guo2021a).

Nexus nodes

Building from the World Economic Forum in 2011, the nexus was recognised from the water–energy–food nexus perspective. While this has been the most common definition, there have been varying interpretations in different sectors and contexts. Nexus thinking is an analytical approach that seeks to identify and quantify the links between the nexus nodes. In this review, nexus concepts analysed in each study were captured and subjected to a word tree to visualise other nexus nodes that have been used. Socio-economics was grouped to represent issues concerning human livelihoods, health, culture and general well-being. Results show that WEF environment has been quite popular in nexus studies (Figure 4). Environment has been a popular node as it addresses broader issues to do with land use, greenhouse gas emissions, carbon footprint and biodiversity (Dhaubanjar et al., Reference Dhaubanjar, Davidsen and Bauer-Gottwein2017; Nie et al., Reference Nie, Avraamidou, Xiao, Pistikopoulos, Li, Zeng, Song, Yu and Zhu2019; Lahmouri et al., Reference Lahmouri, Drewes and Gondhalekar2019; Melloni et al., Reference Melloni, Turetta, Bonatti and Sieber2020; Malagó et al., Reference Malagó, Comero, Bouraoui, Kazezyılmaz-Alhan, Gawlik, Easton and Laspidou2021; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Tan, Zhang, Zhang and Zhang2021; Correa-Cano et al., Reference Correa-Cano, Salmoral, Rey, Knox, Graves, Melo, Foster, Naranjo, Zegarra, Johnson, Viteri-Salazar and Yan2022; Taghdisian et al., Reference Taghdisian, Bukkens and Giampietro2022). According to Simpson and Jewitt (Reference Simpson and Jewitt2019), the environment is an irreplaceable foundation for the WEF nexus as it underpins the security of WEF resources. Figure 4 shows that after the environment, there were many other branches (climate, land, socioeconomics) and sub-branches where climate was linked to land and ecosystems.

Figure 4. Word tree of nexus nodes considered in nexus application studies in the Global South.

Water–energy–food–climate, water–energy–food-ecosystems, water–energy–food–land and water–energy–food-socioeconomics were popular nexus definitions (Figure 4). It was observed that water–energy–food–climate was used in studies focussing on climate change adaptation and resilience of households/communities to climate change (Adom et al., Reference Adom, Simatele and Reid2022; de Souza and Versieux, Reference de Souza and Versieux2021; Diriöz, Reference Diriöz2021; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Assi, Daher, Mengoub and Mohtar2020; Pardoe et al., Reference Pardoe, Conway, Namaganda, Vincent, Dougill and Kashaigili2018; Rasul and Sharma, Reference Rasul and Sharma2016; Yang, et al., 2018; Yue et al., Reference Yue, Wu, Wang and Guo2021a). Like the environment, the ecosystem broadly refers to issues of biodiversity, ecology and the sustainability of the environment (AbdelHady et al., Reference AbdelHady, Fahmy and Pacini2017; Karabulut et al., Reference Karabulut, Udias and Vigiak2019; Müller-Mahn and Gebreyes, Reference Müller-Mahn and Gebreyes2019; Muthee et al., Reference Muthee, Duguma, Nzyoka and Minang2021). Studies addressing the water–energy–food–socioeconomics nexus were more popular at river basin and transboundary scales where livelihoods are directly impacted, especially for small-scale agriculture, fishing and tourism. For example, the consideration of health in the WEF nexus during dam development was highlighted following the transmission of Schistosoma spp. parasites in humans in the Senegal River Basin (Lund et al., Reference Lund, Harrington, Albrecht, Hora, Wall and Andarge2022).

Waste, both urban and economic, was not often used relative to the environment, ecosystem, climate, and socioeconomics (Figure 4). We observed waste to be more popular in studies on urban development. This was also similar to the economy. These nodes were more popular in China, where the WEF nexus was more popular in the context of urban planning and urban metabolism (Li et al., Reference Li, Huang and Li2016; Niva et al., Reference Niva, Cai, Taka, Kummu and Varis2020; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Fan, Zhang, Li, Li, Lv, Shi, Zhu and Qian2020; An et al., Reference An, Liu, Cheng, Yao, Li and Wang2021; Ma et al., Reference Ma, Li, Hu, Wang and Li2021; Qi et al., Reference Qi, Farnoosh, Lin and Liu2022; Zan et al., Reference Zan, Iqbal, Lu, Wu and Chen2022). In some water–energy–food–waste studies, wastewater was proposed for irrigation purposes, thus promoting a circular economy characterised by recycling and reducing pressure on freshwater resources (Lahlou et al., Reference Lahlou, Mackey, McKay, Onwusogh and Al-Ansari2020; Das and Chirisa, Reference Das and Chirisa2021; Ramirez et al., Reference Ramirez, Almulla and Fuso Nerini2021).

Limitations of WEF Nexus applications in the Global South

Data availability allows stakeholders to take stock of economic and environmental resource availability, use and management (Naidoo et al., Reference Naidoo, Nhamo, Mpandeli, Sobratee, Senzanje, Liphadzi, Slotow, Jacobson, Modi and Mabhaudhi2021). Various studies highlighted data limitations as one of the major challenges in the real-life application of nexus approaches. This could have been a result of the unavailability of the data (Perrone and Hornberger, Reference Perrone and Hornberger2016; Ozturk, Reference Ozturk2017; Bellezoni et al., Reference Bellezoni, Sharma, Villela and Pereira Junior2018; Gaddam and Sampath, Reference Gaddam and Sampath2022; Li et al., Reference Li, Li, Fu, Cao, Liu and Li2022), uncertainties stemming from data sources (Perrone and Hornberger, Reference Perrone and Hornberger2016; Ozturk, Reference Ozturk2017; Li et al., Reference Li, Li, Fu, Liu, Yu and Li2021a), scale mismatch (Feng et al., Reference Feng, Chen, Duan, Fang, Li, Jiao, Sun, Li and Hou2022; Han et al., Reference Han, Yu and Cao2020; Nie et al., Reference Nie, Avraamidou, Xiao, Pistikopoulos, Li, Zeng, Song, Yu and Zhu2019) and biases especially in the case of qualitative data (Namany et al., Reference Namany, Govindan, Martino, Pistikopoulos, Linke, Avraamidou and Al-Ansari2021). Naidoo et al. (Reference Naidoo, Nhamo, Mpandeli, Sobratee, Senzanje, Liphadzi, Slotow, Jacobson, Modi and Mabhaudhi2021) emphasised data scarcity at sub-national scales and highlighted other data challenges at all scales related to heterogeneity, disparity, plurality, varied data collection and storage methods, and different data quality and standards. Some governments and organisations in the Global South guard WEF-related data as a matter of national security and sovereignty, while some charge thousands of dollars for long-term data, for example, 30-year multi-station daily climate data. Some custodians who commercialise such data as climate and hydrological claim that selling such data is their only source of income for meeting operation costs towards sustainable data collection without funding from the government and external sources. In a study to track the urban energy-water-land flows within local, regional, national, and global supply chains from the production and consumption perspectives. The sectoral data provided in the World input-output table (Timmer et al., Reference Timmer, Dietzenbacher, Los, Stehrer and de Vries2015) were highly aggregated and limited the reliability of the results (Meng et al., Reference Meng, Wang, Meng, Li, Liu, Yuan, Hu and Zhang2022). When national statistics were used, they misrepresented regional and local variations for various indicators of food, energy, and water security (Mohammadpour et al., Reference Mohammadpour, Mahjabin, Fernandez and Grady2019). In addition, analyses of nexus using political boundaries and administrative-area levels (provinces, metropolitans) limit the ability to extend to other nodes (environmental and ecosystem) that transcend political boundaries.

Concerning qualitative data, Namany et al. (Reference Namany, Govindan, Martino, Pistikopoulos, Linke, Avraamidou and Al-Ansari2021) reported that experts’ judgements can influence the estimation of importance scores. In addition, when experts from a single sector conduct scoring, they are subjective and not in the interest of nexus considerations (Namany et al., Reference Namany, Govindan, Martino, Pistikopoulos, Linke, Avraamidou and Al-Ansari2021). The strength of any quantification tool for nexus depends on the strength of the data. Where data is limited, or there are uncertainties, all the assumptions applied to cover the lack of data and to correct any uncertainties should be performed through sound scientific fundamentals (Bellezoni et al., Reference Bellezoni, Sharma, Villela and Pereira Junior2018; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Niu, Yu, Li, Yang and Ji2022).

Another limitation in applying the nexus approach to real-life case studies was the inability to capture the complexities of those interactions in reality and entirety (Perrone and Hornberger, Reference Perrone and Hornberger2016; Bakhshianlamouki et al., Reference Bakhshianlamouki, Masia, Karimi, van der Zaag and Sušnik2020; Shi et al., Reference Shi, Luo, Zheng, Chen, Hellwich, Bai, Liu, Liu, Xue, Cai, He, Uchenna Ochege, van de Voorde and de Maeyer2021; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Liu, Xia, Wang, Meng, Chen, Mao and Ye2021). A quantification of WEF nexus interactions in the Brahmaputra River Basin, South Asia, using a hydro-economic water system model showed the potential to provide advanced knowledge to inform policy dimensions of natural and social driver changes impact on the WEF nexus (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Ringler, Brown and Mondal2016a). However, the basin’s reality was more complex than captured by the model, which could cause policymakers to resist adopting such an analysis. The model did not consider capital and operational costs of water diversions, the loss of other ecosystem services and the diurnal variations in streamflow (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Ringler, Brown and Mondal2016a). To better represent the real world, agent-based water resources system models are more accurate than centralised optimization frameworks. However, agent-based water resources system models require comprehensive datasets with inherent weaknesses and limitations (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Ringler, Brown and Mondal2016a).

Way forward and recommendations: pathways towards operationalising the WEF nexus in Southern Africa

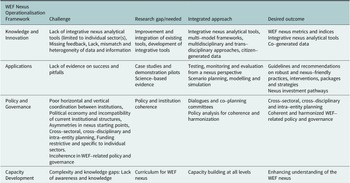

While the literature search focused on the Global South, we propose pathways for operationalising the WEF nexus contextualised for the SADC region. The SADC Regional Strategic Action Plan on Integrated Water Resources Development and Management Phase V highlights the importance of the WEF nexus and the need to have integrated planning and implementation at both a regional and national level (SADC, 2023) Due to the global approach applied in the study, the pathways are generalisable to many global South regions that share a similar context as the SADC. Plausible pathways towards operationalising the WEF nexus are summarised using the Theory of Change (ToC) framework developed by Naidoo et al. (Reference Naidoo, Nhamo, Mpandeli, Sobratee, Senzanje, Liphadzi, Slotow, Jacobson, Modi and Mabhaudhi2021) (Table 5). The crux of the framework was to develop a platform for cross-sectoral dialogues and institutions that can guide key stakeholders to identify and prioritise solutions together from an overall nexus perspective (Naidoo et al., Reference Naidoo, Nhamo, Mpandeli, Sobratee, Senzanje, Liphadzi, Slotow, Jacobson, Modi and Mabhaudhi2021). A ToC clarifies the connections between a given intervention and its outcomes, thus creating a better understanding of what is being implemented and why (Table 5).

Table 5. Accelerating WEF Nexus transition from theory to practice in the SADC region

Bridging the science-policy-practice gap

The inherently vulnerable Global South continues to suffer from thirst, darkness and hunger despite the promises of WEF security through historical sectoral and integrated approaches (Ringler et al., Reference Ringler, Bhaduri and Lawford2013). The security of WEF resources challenges the region and struggles to achieve SDGs, and this is intensified by historical inequities, injustices and imbalances in access and distribution (Murombedzi, Reference Murombedzi2016). For example, Chile currently leads the Global South countries in the overall progress towards achieving all 17 SDGs, but it has a score of 78.22% and is ranked 30th out of all 193 UN Member States (UN, 2022). South Africa demonstrates how historical inequalities contribute to distribution and access to WEF resources and SDG attainment. South Africa is ranked the world’s most unequal country, ranking first out of 164 countries (International Center for Transitional Justice, 2022). This has consequently led to the country being ranked 110th (SDG index score = 64%, global average = 66.7%) with stagnancy in SDGs 2 (zero hunger) and 7 (affordable and clean energy) and moderate improvements in SDG 6 (clean water and sanitation) (UN, 2022). Disparities exist in access to WEF resources between South Africa’s urban and vulnerable peri-urban, rural, and informal settlements (StatsSA, 2019; 2023). Zimbabwe is ranked 138th (SDG index score = 55.6) with stagnancy in SDG 2 (zero hunger), a decrease in SDG 6 (clean water and sanitation) and moderate improvements in SDG 7 (affordable and clean energy). Implementing the WEF nexus approach with equal consideration between social groups can redress inequity and inequality through just transition, social justice, and sustainable and equitable development of society towards low-carbon economies in the Global South (Murombedzi, Reference Murombedzi2021). Nexus implementation must consider outcomes for the poor and vulnerable to not compromise their well-being (Ringler et al., Reference Ringler, Bhaduri and Lawford2013).

Global changes in climate exacerbate the WEF challenges in the Global South, which are also amplified by pandemics (e.g., COVID-19) and conflicts (e.g., Russia-Ukraine) that disrupt the supply chains of food (grains, cooking oil), fertiliser and energy (fuel, gas). Interlinkages between climate change and WEF resources are forward and backwards because climate change affects WEF resources and sectors (Rasul and Sharma, Reference Rasul and Sharma2016). In the current era of climate change, global warming, and climate variability, the need arises to consider the climatic dimension in the nexus thinking equally for an inter-sectoral response. Similarly, climate mitigation and adaptation should be planned and implemented from an integrated nexus perspective to minimise maladaptation. Thus, a paradigm shift from a vicious cycle of conventional sectoral management approaches to a potentially virtuous cycle of implementing nexus approaches is more likely to accelerate the inclusive achievement of the COP21 Paris climate change commitments and SDGs. An equally important dimension in the nexus is the environment. Nexus deliberations must account for environmental outcomes to preserve and maintain ecosystems that underpin the security of WEF resources (Ringler et al., Reference Ringler, Bhaduri and Lawford2013).

The WEF nexus promises to simultaneously and collectively achieve the security of water, energy and food through improved allocation and efficiencies. The approach has progressed significantly, if not rapidly, in the research and policy space, although implementation is still in its infancy. Science through the research dimension has enhanced understanding and knowledge of the concept, developed relatively abundant tools, and amassed volumes of evidence. Similarly, the policy space has congregated decision-makers in dialogues that promote collaboration, sharing and integration. The Global South must contextualise the WEF nexus tools, evidence and relevant policies into actionable strategies, programs and actions that can be implemented, from pilots to full-scale, for just and inclusive transitions and transformations that leave no one behind in sustainable development. For example, dialogue findings can be used to develop coherent nexus-friendly policies. In contrast, lessons from nexus and scenario planning studies can be used to develop harmonised and integrative incremental and transformative pathways whose scenarios can be exploratively simulated by WEF nexus modelling tools. Promisingly optimal intervention(s) that optimise synergies and minimise trade-offs are combined into WEF investment packages, which are piloted so that their real-life impacts can be evaluated and monitored. Challenges are noted, lessons are learnt, and improvements are made for deep-, out- and up-scaling.

Addressing data needs to enable nexus applications

There is a high demand for quantitative and qualitative data and information to apply nexus models and frameworks. Nexus applications have relied heavily on secondary databases, which are largely sectorial and limited in depth, accuracy and spatial and temporal scale. The type of data, its format, and its accuracy are important for developing nexus tools and their usefulness and reliability in solving real-life challenges. Researchers need to clearly outline data needs at different scales from relevant authorities to satisfy WEF tools. This should be complemented by standardised data collection protocols that can guide data collection and ensure good quality and uniform data comparable across scales, space and time is obtained. Government departments, academia, research organisations, and development agencies are encouraged to collaboratively follow strict data curation practices to ensure that high-standard data is available and easily accessible. The development of nexus tools should also balance both simplicity and accuracy with minimal data input requirements.

Building and strengthening capacity for WEF nexus adoption and application

WEF nexus research still largely exists at an academic and scientific level, especially in the Global South (Lazaro et al., Reference Lazaro, Bellezoni, Puppim de Oliveira, Jacobi and Giatti2022). The move to Open Access is changing this. However, much research is still pay-walled, and some targeted end users of the research findings, such as policymakers, lack the skills to understand and translate scientific evidence (Cairney and Oliver, Reference Cairney and Oliver2017; Gollust et al., Reference Gollust, Seymour, Pany, Goss, Meisel and Grande2017). From the perspective of some policymakers, some main barriers to accessing scientific literature include time to read papers and difficulty in understanding technical language (Karam-Gemael et al., Reference Karam-Gemael, Loyola, Penha and Izzo2018). Thus, concise packaging of the relevant information is needed, paying particular attention to what information needs to be transferred to policymakers and how to package and present it to improve the likelihood of using it (Strydom et al., Reference Strydom, Funke, Nienaber, Nortje and Steyn2010). There is a need to build and strengthen the capacity of researchers, practitioners and policymakers to jointly undertake nexus assessments and translate the evidence into policy and practice outcomes, especially in the context of investment and sustainable development planning. Such capacity-building should consider the regional context and integrate the biophysical and socio-ecological systems to enhance people and planetary benefits across multiple scales (from farm or village to country and region). This requires transdisciplinary approaches that cut across disciplines, sectors and actors to ensure impact.

Study limitations

The review used the PRISMA guidelines to identify, select, appraise, and synthesise studies. Due to the use of predefined search terms and inclusion criteria, some literature may have been excluded. The search was also done in scientific databases (WoS and Science Direct), thus excluding other potential sources of ‘grey literature’ such as reports and theses that are not all included in scientific databases. During synthesis, the study identified two major drivers of nexus applications: (i) to improve understanding and to generate knowledge on WEF interactions; and (ii) for planning purposes and as a decision support tool. While the categorisation was subjective, the authors represent expertise in the science and public space and are experts on the WEF nexus. While the pathways are contextualised for southern Africa, the literature review was at a Global South level due to limited research outputs specific to the region.

Conclusions

We reviewed WEF nexus applications in the Global South to develop pathways for WEF nexus operationalising at a regional scale. There is a drive to shift from nexus theory to practice. Hence, there has been a surge in studies aiming to validate nexus tools and improve understanding of nexus interactions at different scales (Al-Saidi et al., Reference Al-Saidi, Daher and Elagib2023). These studies have been valuable for knowledge generation and provide optimism on the possibilities of nexus approaches for solving real-world problems.

Nexus nodes are not limited to the default water, energy and food. The approach has extended to address global challenges such as climate change, environmental degradation, land scarcity, and livelihoods. This highlights the catalytic nature of the WEF nexus approach and how it can facilitate broader systemic change.

Data availability, quality, and scale mismatch concerns could hinder applying nexus approaches to solve problems. However, this should not be a deterrent. Data limitations can be overcome through sound methods when making assumptions and statistical methods to (dis)aggregate and down/upscale data to suit a specific scale.

The inability of nexus approaches to capture reality was also cited as a major limitation; however, we believe no model is perfect and is a true representation of reality. Models should aim to capture important aspects of the system and accurately respond to changes in input variables while addressing the questions and objectives in focus. That ability to respond to input variables and show trends is important for planning and decision-making. Recommendations towards operationalising the WEF nexus include bridging the science-policy-practice gap, generating data for developing and applying nexus tools and building capacity within students, researchers and practitioners. While these recommendations are contextualised for southern Africa, they are transposable to other global South regions with a similar development context.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/wat.2024.8.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/wat.2024.8.

Author contribution

T.M., Conceptualization, Writing—Original draft preparation, critical review and redrafting; T.P.C., Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Writing—Original draft preparation; C.T., Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Writing—Original draft preparation; T.L.D., Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Writing—Original draft preparation; and A.N., Critical analysis. All authors revised and edited the manuscript.

Financial support

The SADC Nexus Dialogue Project “Fostering Water, Energy and Food Security Nexus Dialogue and Multi-Sector Investment in the SADC Region,” which was supported by the European Commission as part of the global ‘Nexus Regional Dialogues Programme”. This work was funded, in part, by the Nexus Gains Initiative, which is grateful for the support of CGIAR Trust Fund contributors: www.cgiar.org/funders. The Water Research Commission of South Africa is also acknowledged for funding through WRC CON2022/2023-00910. The work was funded, in part, by the Sustainable and Health Food Systems – Southern Africa (SHEFS-SA) Project, supported through the Wellcome Trust’s Climate and Health Programme [Grant No 227749/Z/23/Z]. For the purpose of Open Access, the author has applied a CC BY public copyright licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Comments

Centre for Transformative Agricultural and Food Systems,

School of Agricultural, Earth and Environmental Sciences,

University of KwaZulu-Natal,

P. Bag X01,

Pietermaritzburg 3209,

South Africa

15 November 2023

The Editor(s)

Cambridge Prisms: Water

Dear Sir/ Dear Madam,

We wish to submit a review entitled “Review of Water-Energy-Food Nexus Applications in the Global South” for consideration to publish in Cambridge Prisms: Water. We confirm that this work is original and has not been published elsewhere, nor is it currently under consideration for publication elsewhere.

In the paper, we synthesize research on WEF nexus applications to identify how WEF nexus tools have been applied to facilitate knowledge generation and decision-making in the Global South and some opportunities and challenges arising from these efforts. Optimistic opportunities for applying nexus approaches for solving real problems and informing policy decisions are identified. The review will be of value to scientists and practitioners as it outlines recommendations towards operationalizing the WEF nexus.

We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Please address all correspondence concerning this manuscript to Mabhaudhi@ukzn.ac.za

Thank you for your consideration of this manuscript.

Sincerely,

T. Mabhaudhi