Grand hoteliers in Berlin and elsewhere made it a pillar of their business model to exclude most people. Yet, such exclusivity depended upon the presence of hundreds of working-class people who toiled, ate, and slept in the hotel. Interclass equilibrium rested on the existence of a strict, intricate hierarchy for workers and unspoken norms of dress and comportment for guests, among whom interregional and international equilibria were prerequisite. How was it possible to bring together and sustain equilibrium among such vastly different social groupings, and what does the maintenance of that equilibrium tell us about the nature of bourgeois power in imperial Berlin?

In grand hotels, the classes and nations mixed in higher concentrations than anywhere else except the ocean liner. As on ocean liners, grand hotels offered spaces for the elite exercise of freedom under conditions of staff surveillance and mutual policing on the part of the guests. These practices, facets of the liberal order, continued until August 1914, when everyone – guests, white-collar employees, managers, workers, owners – went to war. Then, and all of a sudden, violence erupted in grand hotel lobbies under the impotent gaze of the chefs de reception. In one blow, World War I shattered the liberal ideal upon which Berlin’s grand hotels were founded. That ideal, dependent upon an equilibrium supported by little more than architecture, regulation, and unspoken rules, had serious weaknesses, it turned out.

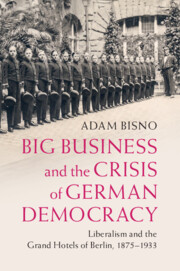

The tensions had always been there. A postcard from the Hotel Schaurté from around 1900 encapsulates the ironies and contradictions of grand hotel culture in the Wilhelmine era (Figure 2.1).Footnote 1 In the foreground, a military parade traverses the frame, and in the background, a crowd of spectators is assembled in front of the hotel. Festooned on the beaux-arts facade (in the French style) are advertisements for a “restaurant français” and English “grill room,” while at the same time a parade of Prussian and imperial might proceeds down the street. Nationalist and cosmopolitan references perch together here in a delicate balance.Footnote 2

Figure 2.1 Promotional postcard from the Hotel Schaurté, ca. 1900

In the Pleasure Zone

The consumer economy of Friedrichstadt and its environs, Berlin’s grand hotel district, attracted ever larger, more heterogeneous crowds until the outbreak of World War I.Footnote 3 Food was a major draw. The 1904 edition of Baedeker’s listed dozens of first-class restaurants, including those of the luxury hotels, as well as the wine houses Rheinische Winzerstuben, Eggebrecht, and Zum Rheingau. Down-market options also abounded, especially beer halls for men: Augustinerbräu, Pschorrbräu, Sedlmayr zum Spaten, Weihenstephan, Tucherbräu, Münchener Hofbräu, and Dortmunder Unionbräu. Women tended to frequent the cafés and cake shops (Konditoreien). At least one café, Buchholz, had the reputation of being “visited almost exclusively by women.” The cafés Viktoria and Kranzler occupied the most prestigious intersection of Friedrichstraße, at the corner of Unter den Linden, while up and down that boulevard, Leipziger Straße, and the side streets lay plush concessions such as the cafés Klose, Reichshallen, and Kaiser.Footnote 4 The neighborhood had been given over to shopping, dining, entertainment, and the sexual commerce attending those activities.Footnote 5

At the northern end of Friedrichstraße, near the station and the Central-Hotel, loomed the grandest bathhouse in Berlin, a gargantuan spa and entertainment establishment. For dry amusement, there were several shopping arcades, including the Kaiser-Galerie, with its panorama, cabaret, and food and fashion concessions.Footnote 6 “The best shops” were in an area comprising Friedrichstraße and Leipziger Straße. There were department stores and stores specializing in jewelry, books, antiques, engravings, furniture, furs, glassware, hats, lace, leather, fabric, perfume, porcelain, silk, and underwear. The “Mourning Warehouse” of Otto Weber catered on multiple floors to every stage of public grief.Footnote 7 Throughout the district, men, women, and children – consumers and clerks, foreigners and locals, sex workers and bourgeois ladies, aristocrats and thieves – circulated in proximity.Footnote 8

This heterogeneity presented dangers and pleasures alike.Footnote 9 Hans Ostwald, editor of the Großstadt-Dokumente (Documents of the Metropolis), a massive, multivolume sociology of Berlin, titillated readers with copious description of an urban underworld in plain sight. Moralists complained about prostitutes “openly” plying their “horizontal wares” in ordinary cafés.Footnote 10 For their part, the police carefully collected information on the infractions of Friedrichstadt’s demimonde.Footnote 11 They harassed women circulating through the city, as did barkeeps, café maîtres d’, and restaurateurs.Footnote 12 Urban reportage and fiction published in both elite and popular serials represented Friedrichstadt as replete with vice and dangers – it was an area inhospitable to bourgeois women, even as it beckoned them to enter as consumers. In 1913, one department store went so far as to send engraved invitations to ladies of the finest households in town; the same store then ran afoul of the authorities by populating its window displays with lifelike mannequins in various stages of undress.Footnote 13 The mix of dissolution and respectability, sex and commerce, danger and pleasure, was the neighborhood’s defining feature.

These layers of ambivalence alienated many observers. “Ruthless progress” in the city had produced a “clumsy young giant with all the ungainliness that comes after too fast a growth spurt,” a “world city in the constant state of becoming,” “immoderate,” and ready to “grab indiscriminately at the pleasures of life.” Friedrichstadt was also a meeting point for the deracinated.Footnote 14 As Kurt Tucholsky famously quipped, “the sense of home has … become transportable” and Berlin the capital of “the impersonal, the unconnected, the strange, and the ambivalent.”Footnote 15

Berlin’s grand hoteliers responded by positing their establishments as the best mediators between the consumer and the pleasure zone. In answering questions and providing maps and recommendations, hotel staff made the city intelligible, navigable, and accessible. In-house theater and railroad booking agents, carriage and courier services, currency exchanges, and barber shops – these amenities helped a guest manage, interact with, and be ready for a metropolis that by the early 1900s was the fastest-growing capital city in Europe.

Parvenus

Berlin was also one of Europe’s newer national capitals. Locals and visitors alike identified it as the parvenu metropolis, comparable to Chicago in its heavy industry, flashy architecture, and central location in a continental railroad network.Footnote 16 The comparison was common enough that it appears in a turn-of-the-century book promoting the Savoy Hotel.Footnote 17 As a large European capital, however, Berlin also invited comparison with Paris and London. Walther Rathenau saw Berlin, or “Parvenupolis,” outpacing those cities, now old and tired.Footnote 18 Still others thought Berlin lacked the patina of West European capitals.Footnote 19 The city’s architecture, a symphony of buildings and building styles that expanded in the 1860s and exploded after 1871, was cacophonous by 1900. To critics, the city lacked pedigree.Footnote 20 To its fans, that very lack appeared to open a range of new possibilities, especially for the thousands of moneyed Germans who arrived every day, some to stop and some to stay, all with needs that grand hotels stood ready to meet.

Berliners oscillated between seeing Berlin as a Parvenupolis and a Weltstadt (world city).Footnote 21 The Zentralblatt der Bauverwaltung (newsletter of Berlin’s construction administration) reported in 1907 that this “youngest of world cities” did not have enough hotels near railroad stations, a problem that the Hotel Baltic, an establishment near Stettin station and one of the “more dignified constructions in the Weltstadt Berlin,” was supposed to solve.Footnote 22 The understanding of Berlin as a Weltstadt redirected urban development toward grander projects, as historian Peter Fritzsche has observed.Footnote 23

The grand hotel scene saw a flurry of new construction in the decade before World War I. In his description of the new Hotel Adlon in 1908 for the publication Innen-Dekoration, Anton Jaumann celebrated the building’s potential: “It takes the competitive edge from those wonderful luxury hotels with which New York, Paris, and London once showed their superiority.”Footnote 24 Jaumann and others presented the city’s grand hotels as signs and symbols not just of the city’s arrival on the world stage but also of its preeminence there.

This municipal jingoism reflected an inferiority complex pervasive among Berliners, celebrants and detractors alike. In an article on why Berlin did not need any more foreign visitors than it was already attracting, a contributor to the Berliner Tageblatt disparaged his city as unsophisticated, not “broad-minded enough to become a city of foreigners (Fremdenstadt) like Paris.” In industry and growth, “of course,” Berlin had “been overtaking Paris throughout the last generation,” according to the Scottish town planner Patrick Geddes, but the German capital lacked status.Footnote 25 Disjointed and rough, Berlin was “missing a merging point” for the great and the good, a local journalist complained.Footnote 26 In the eyes of Julius Klinger, a graphic artist from Vienna, the city’s beau monde lacked a je ne sais quoi: “In the [Hotel] Bristol at breakfast … one can see the upstanding gentlemen and sophisticated socialites in the style of Ernst Deutsch [one of Berlin’s most celebrated commercial illustrators] but in their live form, they do not come close to attaining the charm of the illustrated.”Footnote 27

The same seemed true at other hotels and other mealtimes. Hungry after the opera one night in 1912, the cultural critic and literary scholar Arthur Eloesser and his friend from the provinces decided on a late dinner in the grill room of a first-class hotel. (Grill rooms were informal dining concessions, where patrons ordered à la carte.) Eloesser’s account inventories gilded mirrors, blue silk wallpaper, and “opulent” furnishings. Yet the luxury was missing “that last stamp”: a sense of “peace,” the “imperturbability of naturalness.” The interiors had an aristocratic touch, to be sure, complemented by “waiters in the livery of court lackeys,” but the evidence of an effort was too great. The grill room was trying too hard, and in the trying, it belied its authenticity as an informal space of noble repose.Footnote 28 This assessment of the grill room’s ultimate failure, through excessive striving, to be truly elegant provided Eloesser a metaphor for Berlin itself.

Some of the failures were real. In the decade before World War I, Berlin’s hoteliers faced a shortfall in foreign custom. Although tourism to the city had increased after 1900, the duration of a single stay in Berlin was short relative to Paris and London.Footnote 29 In June 1908, for example, Berlin’s hotels seemed to be full of Americans, but most of them were using Berlin as a post on the routes to and from spas in southern Germany, Austria, and Switzerland. In other cases, Berlin became the last stop of a European tour, a place to change trains and rest a little before continuing to Hamburg and a steamer home. By 1913, according to The New York Times, Berlin had “degenerated into a mere way-station for American travelers,” not a destination in its own right.Footnote 30 This fact alarmed hoteliers and piqued their envy. Why should Berlin not hold its own against Paris and London?

In 1911, when the World Congress of Hoteliers (founded only a few years earlier) held its meeting in Berlin, the Association of Berlin Hoteliers (Verein Berliner Hotelbesitzer) lobbied the city government for support.Footnote 31 In advance of the event, Ernst Reissig, president of the association, wrote to the lord mayor (Oberbürgermeister) and the magistrate to ask that they receive a delegation from the World Congress. After all, the mayor of Rome had done the same for the last congress, Reissig wrote.Footnote 32 Here was a chance to impress a large group of important foreigners who might go home and give favorable reviews of what they had seen in Berlin.

The program for the World Congress of 1911 aimed to impress. It included events at major hotels and tourist attractions, as well as a banquet and ball at the Zoologischer Garten (zoo). According to the participating institutions – the Universal Federation of Hoteliers’ Associations (Fédération Universelle des Sociétés d’Hôteliers), the International Association of Hotel Owners, and the Association of Berlin Hoteliers – the purpose was to provide an “international conference” that would “give testament to the sense of solidarity felt by all members of our profession,” regardless of nationality. And this cosmopolitan pose would be modeled for prominent Berliners. Dozens attended, including the lord mayor, the mayor, the president of the Central Bureau of Tourism (Centralstelle für den Fremdenverkehr), and the editors of the city’s largest newspapers.Footnote 33 Their presence reinforced Berlin hoteliers’ commitment to a stance of openness toward the foreign, on the one hand, and the desire to compete, on the other.

Nationalists

Berlin was brimming with sites of local, Prussian, and national-imperial pride that attracted domestic and foreign visitors alike. Hoteliers exploited the city’s status as the capital of the German Empire by touting connections to royalty, even as the construction of new hotels and other buildings erased traces of Berlin’s past as a principal Residenzstadt (royal seat) of the bygone German Confederation and, before that, the Holy Roman Empire. Near the palace, Mühlendamm, once the city’s major commercial thoroughfare, had lost its calling to Friedrichstraße by the 1880s. By the end of the century, few Berliners would have remembered the old city hall, replaced in the 1860s with a gargantuan building of little relation to the original.Footnote 34 Wilhelm II had Schinkel’s stately, small cathedral on Spree Island razed and replaced with something suited to the bombastic Protestantism of the last Hohenzollerns. Royal and noble residences were also torn down to make way for hotels like the Adlon. In these cases, hoteliers tended to preserve in advertisements the memory of what had come before. Having supplanted the site of the palace of Prince Louis Ferdinand, the Savoy Hotel distributed promotional books that traded on his reputation as “the hero of Saalfeld,” a lost battle against Napoleon’s forces in 1806.Footnote 35

Alongside the Prussian tradition, Berlin’s relatively new status as imperial capital generated extra revenue and opportunities for hoteliers. The Adlon became a focal point of informal state business, Prince Bülow having stayed there regularly after his retirement in 1909 and granted audience not only to admirers but also to the emperor’s advisers.Footnote 36 To broadcast their hotel’s pride of place in such official circles, the Adlon family made sure to fly the imperial flag as high and prominently as it could, at the corner of the building facing the Brandenburg Gate and thus along the route from the emperor’s palaces at Potsdam to his residence at the other end of Unter den Linden.

The excess of imperial flags across the Adlon’s frontages advertised the hotel’s special relationship with Wilhelm II, as the Kaiserhof had done with Wilhelm I, though to a greater extent. In fact, the Adlon became something like the Court Hotel even before it opened. Jaumann wrote of “all Berlin” following the hotel’s construction because the emperor himself had given the project and building plans his precious attention. To Jaumann, this meant the emperor’s own “acknowledgment and support of the international implications of the undertaking.” The Adlon “should show the excellence Germany is able to obtain in all respects: in luxury, in comfort, in hygiene.”Footnote 37 Inside, the emperor’s likenesses graced fireplaces and niches, with especial prominence in the banquet hall, where his bust complemented portraits and royal-imperial insignia. Many showed him in armor as the Supreme War Lord of Germany, one of his official titles, in an era of frequent, ominous, near-miss conflicts among the Great Powers.Footnote 38

At other hotels, designers and owners avoided displays of militant nationalism or balanced them with cosmopolitan touches. At the Central-Hotel, guests passed through sumptuous public rooms outfitted in a pastiche of French, not German, styles to get to the restaurant Zum Heidelberger, a showcase of German regional decor but not Prussian or German-imperial militarism (Figure 2.2). Several themed rooms, borrowing from local traditions, comprised a grand tour of German beer hall design. For guests from elsewhere in Germany, Zum Heidelberger peddled an alternative nationalism to that of the Adlon. Where the Adlon and other hotels signaled Prussian hegemony, Zum Heidelberger assembled the riches of regional histories to conjure an earlier, idealized Germany of loosely confederated principalities, united by a single language and shared traditions, free from the political machinations of Berlin.Footnote 39 The decor made sense at the Central, a magnet for business travelers from all over the Reich.

Figure 2.2 Promotional postcard for Zum Heidelberger, the Central-Hotel’s beer hall, ca. 1900

At the same time, the Central broadcast mixed messages about its roots and its purpose. Notwithstanding the Germanism of the sign promoting Zum Heidelberger, the exterior of the building (1880) was decidedly French, and the French fashion, after the Parisian example, proliferated at Berlin’s grand hotels well into the twentieth century. One critic, writing for the B.Z. am Mittag, found the trend insupportable: “It so happens that we in Germany have the greatest of strengths at our disposal [for creating] buildings of the hotel and commercial variety,” yet the use “of the French style” continued. The contributor saw this as an insult, as would the emperor, who believed that the use of French and other foreign motifs in the architecture of the capital undid the achievements of his dynasty.Footnote 40 For architects and designers, there was always the pressure to revert to the idioms of the Volk or the Prussian tradition.Footnote 41 And yet, these pressures counteracted the nationalist drive for Berlin to be the German Weltstadt, a showcase of cosmopolitanism, which would attract and retain the custom of foreign social, cultural, academic, and political elites.

Cosmopolitans

The cosmopolitanism of grand hotel guests manifested along several lines: the cosmopolitanism of the aristocracy and royalty who visited; the accentuation and celebration of difference among national groups within the grand hotels; cultural exchange among such groups; the phenomenon of intermarriage, particularly between American women and German men; and even sexual nonconformism. The early 1900s was a heyday of cosmopolitanism, which Judith Walkowitz has called the “privileged stance of openness toward abroad,” exemplified by the tango craze, the success of the orientalism of the Ballets Russes, and the appeal of exotic dancing.Footnote 42 The cosmopolitanism of the grand hotels could be more mundane, too – utilitarian even, particularly among the staff, whose openness to abroad had to be a fact of everyday life.Footnote 43

Berlin’s grand hotels, especially the Adlon, Esplanade, and Continental, mimicked the private accommodations of royalty and the high aristocracy.Footnote 44 Services were modeled on the well-run households of the nobility, so that guests enjoyed “elegant breakfast[s] served on huge silver platter[s],” as journalist Marion Dönhoff remembered of her East Prussian childhood. At her family’s Schloss Friedrichstein, as in a grand hotel, “formal dinners” featured “a constant stream” of guests “from the world of diplomacy, the upper nobility, and the intellectual elite.”Footnote 45 Berlin’s finest grand hotels supported the urban version of this elite cosmopolitan sociability.Footnote 46 For the 1913 wedding of Princess Victoria Louise of Prussia to Ernest Augustus of Cumberland, descendants of George III of Great Britain, the court reserved “entire floors of fashionable hotels” for the accommodation of “so many different royal personages.” The New York Times described the event as “an aristocratic cosmopolitan galaxy of ladies and gentlemen in waiting on the rulers of Russia, England, Italy, Denmark, and Austria.”Footnote 47 Such spectacles involved a cast of characters who stood above nationality, whose connections and customs set them apart from national groupings altogether.

In addition to tending to such royals and aristocrats, Berlin’s grand hoteliers had to accommodate commoners from all over Europe and the world. This group, the bulk of the clientele, identified more closely with their nationalities than did royalty and the high aristocracy. Thus, certain national groups gravitated toward certain hotels. The Baltic Hotel, for example, attracted Danes, Swedes, and Norwegians. Americans liked the Adlon, the Fürstenhof, and the Esplanade.Footnote 48 And then there were the occasional visitors from farther afield. The New York Times reported in 1912 that “a touch of color was lent to the exclusively Caucasian guest list at the Adlon this week by the arrival of the Indian nabob, Sir Rajenda Mockerjee [sic] and Lady Mockerjee [sic] of Calcutta,” racializing its story and referring to the Bengali Indian industrialist-engineer Rajendra Nath Mookerjee and his wife. Mookerjee traveled extensively in Europe, delivering speeches on corporate management, labor relations, imperial rule, and political economy.Footnote 49 For distinguished guests of all nations, hotel staff had to create and maintain a pleasant, secure, and peaceful home away from home.

When it involved people of rank, guests themselves had to ensure that cultural exchange would happen along civilized, prescribed lines. One night in August 1911, General Nogi Maresuke of the Imperial Japanese Army was dining in the Adlon restaurant. As he rose to leave the table, he found himself being assailed by an American guest, who, in front of all the patrons, including a few dozen Americans, gave the general a slap on the back and exclaimed, “Good old Nogi! Hurrah for Japan!” Many of the Americans present became incensed and met immediately to discuss the incident and find a way to tell “their effervescent fellow countryman what they thought of such an exhibition.”Footnote 50 Such breaches threatened to tarnish the reputation of Americans in Berlin, who policed each other accordingly.

No group made itself at home more insistently in Berlin’s grand hotels than did the Americans. For a time in 1908, the US ambassador to Germany actually lived at the Adlon. Two years later, in May 1910, The New York Times reported on a wave of American tourists “now in full possession of Berlin hotels, shops, summer gardens, and all other establishments in the Kaiser’s town that cater for foreign patronage.” That same year, in the month of June alone, nearly 4,000 Americans had taken rooms in hotels and pensions, with the Adlon, Kaiserhof, Bristol, and Esplanade accepting the majority of the elite custom. Such was the critical mass at the Adlon, Bristol, and Esplanade in July that crowds gathered in the lobbies to wait for The New York Times to announce the latest news of a boxing match in Reno.Footnote 51 American visitors en masse made spectacles of themselves, and hoteliers were eager to accommodate them, given the depth of the American market and of individual Americans’ pocketbooks.

Cultural exchange between Anglo-Americans and Germans ensued, especially in sports and entertainment. In the early twentieth century, a group of American and British men founded the city’s only golf club and used hotel spaces for meetings. As late as 1912, the club “remain[ed] … pretty much of a monopoly of the Anglo-American element.” Two years later, however, the club had become “largely Teutonic.” Meanwhile, in 1911, the Adlon became a nexus of transatlantic entertainment when James C. Duff and his wife arrived in pursuit of new acts for their lineup on Broadway. The hope, according to The New York Times, was that Max Reinhardt, among others, would be persuaded “to present some examples … in the United States.” Duff and others relied on institutionalized networking under the auspices of the Adlon, where the American Luncheon Club promised to connect American visitors and expatriates with prominent Berliners.Footnote 52

The American Luncheon Club and its members facilitated a flurry of transatlantic academic and philanthropic exchange, too.Footnote 53 In 1908, Andrew Carnegie had the cast of a diplodocus skeleton delivered to Berlin. He sent a representative of the Carnegie Museum of Pittsburgh to be the special guest of honor at a celebratory dinner at the Adlon. Exchanges like these occurred until the outbreak of World War I. In 1913, a member of the board of the Christian Scientists’ principal church, in Boston, gave a speech in German to a sizable crowd in the Adlon’s Beethoven Parlor.Footnote 54

This academic cosmopolitanism had diplomatic implications. Here was a model for how liberals across the world might use free trade and the exchange of ideas to avoid war. At the 1909 annual banquet of the American Association of Trade and Commerce, held at the Adlon, the US ambassador expressed hope that free trade might silence “the voice of the ‘jingoes’” and cause “passions to be still.” In 1911, the ambassador repeated this argument in his farewell dinner at the Adlon, confessing, “We in America have hopes for a more closely united world.” States and governments should avail themselves of “the gift of mutual interpretation,” the ambassador continued. If he did not go so far as to propose a cosmopolitan vision of world citizenship, he did insist that “law, justice, and righteousness … [were] things applicable internationally” – even as American and German foreign policy were becoming ever more aggressive. Under these conditions, Andrew Carnegie came to Berlin in June 1913 to present an address to the emperor on behalf of dozens of American peace societies. Carnegie stayed, naturally, in the royal suite of the Adlon, where so much had already been said for a cosmopolitan worldview that favored international friendship and peace.Footnote 55

The following year, some four months before the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife in Sarajevo, Archibald Cary Coolidge of Harvard University and Paul Shorey of the University of Chicago, two visiting exchange professors, bid farewell to Germany at the Adlon’s Kaisersaal. The dinner held in their honor, which attracted the “aristocracy of German intelligence,” was one of the greatest ever “aggregation of brains gathered around a Berlin banquet board,” including Max Planck, Adolf von Harnack, and the city’s most eminent scholars of medicine, history, archaeology, and classics. Harnack gave a toast to the “quadruple intellectual alliance of Germany, America, England, and Austria-Hungary,” whose succuss he believed sprang from a common Germanic heritage, an imaginary alliance founded on racist mythology and wishful thinking.Footnote 56

The alliances that received by far the most press, however, were engagements and marriages between German men and American women. In 1909, the widow Elsie French Vanderbilt became engaged to Count Wilhelm von Bentinck, a member of the Potsdam guards, but the agreement fell through when his relatives dissuaded him from this union of unequals. In 1913 alone, a wealthy woman from Detroit, a widow from Philadelphia, and a granddaughter of a former ambassador to Berlin found advantageous matches among Germany’s elites. Although the ceremonies themselves happened in churches, it was common to hold the ball, banquet, and wedding breakfast at the Adlon or other such establishment. The city’s grand hotels also became places where American wives of German aristocrats could reunite with friends, display new status, help organize intermarriages for others, and find opportunities for charity work in the dense network of liberal women’s urban interventionism.Footnote 57

Grand hotels, particularly the Adlon, provided space for women to engage themselves in diplomatic circles, too. At the Adlon in 1908, the US ambassador’s first Berlin reception had barred women’s entry “in accordance with the strict rules of the Kaiser’s capital.” But unofficial events were open to women and even came to be their distinct purview. In the relative privacy of her apartment in the Adlon, Bertha Palmer of Chicago entertained the US ambassador and other prominent Americans and Europeans.Footnote 58 In 1913, two unmarried sisters from Washington, very much at home “in diplomatic circles on both sides of the Atlantic,” had a dinner given in their honor by the French ambassador to Berlin.Footnote 59 The grand hotel was thus a place where women could entertain and be entertained by a diplomatic set otherwise off limits. These engagements played out in more public spaces such as sitting rooms, dining rooms, conference rooms, and ballrooms, not the private areas upstairs, where access still depended in most cases upon a male chaperone.

Berlin’s grand hotels hosted well-to-do women even as vice persisted there and elsewhere in the city center. Here was the dark side of cosmopolitanism, its association with sex and even sexual danger.Footnote 60 Iwan Bloch, medical doctor and author of Das Sexualleben unserer Zeit (The Sexual Life of Our Time), attributed the increased publicity of vice to an expanding, accelerating circulation of people and information more generally. With the advent of mass media, sex played a “greater, more meaningful role” in public than it had before, he claimed.Footnote 61 Men were now taking out ads in newspapers to request the addresses of women they had seen on trains, trams, and omnibuses.Footnote 62 Prostitution, both male and female, flourished, particularly in hotels, as Oscar Commenge noted for Paris in 1897 and Ostwald observed for Berlin in his 1906 study of male sex work.Footnote 63 Two of the city’s principal cruising grounds could be found in and around Friedrichstadt. The Central-Hotel was located on one of them, Friedrichstraße itself. The Bristol was located on another (Unter den Linden). Many of the other grand hotels lay within walking distance of the Tiergarten, which contained its own crowded cruising area.Footnote 64

Grand hotels attracted gay men, especially powerful ones. Events at the Bristol in 1902 precipitated the greatest homosexual sex scandal in Germany to date. There, the great industrialist Friedrich Krupp (scion of Alfred) was supposed regularly to have entertained a handful of Italian pages. The hotel manager had hired them for Krupp’s private gratification, the socialist publication Vorwärts reported. The editors, trying to take down Krupp, implicated the Bristol and its management in an international economy of exploitative pederasty. Such rumors piqued the attention of the chief inspector (Kriminalkommissar) Hans von Tresckow, who launched an investigation. In the glare of this publicity, Krupp committed suicide.Footnote 65

In their advertisements, of course, hoteliers presented the lighter side of cosmopolitanism in the pleasure zone. They emphasized the international profile of their clientele and the concessions renting space on their ground floors.Footnote 66 In 1912, the Adlon let the location of its grill room to the steamship company North German Lloyd.Footnote 67 The Kaiserhof housed a branch of the Hamburg-based Havana Import Company, where guests and visitors could buy exotic tobacco products.Footnote 68 The Savoy boasted twenty French cooks, and the Palast-Hotel made sure to print its menus in both French, prominently, and German, in smaller type. As if to temper this favoring of the foreign, the restaurant manager had the menu decorated with the heraldry of nine of Germany’s princely houses.Footnote 69 Where hoteliers responded to cosmopolitan cultural imperatives, they liked to balance the effects with local, national, and German-imperial symbols.

While the early grand hotels such as the Kaiserhof and the Central in the 1870s and 1880s had balanced German art and symbols with French décor, Berlin’s grand hotels of the 1890s and 1900s added American offerings to the mix as part of the imperative, first, to appear welcoming to new sorts of visitors from much farther away and, second, to appear open to the foreign after the cosmopolitan fashion of the day. In 1904, the Kaiser-Keller, a large gastronomy concern, opened an “American bar,” which the management nonetheless decided to call the “Kaiser-Büffet.”Footnote 70

One hotelier came to the United States in 1911 chiefly for the purpose of learning the art of American bartending. He “made the rounds of the new hotels in all the leading cities of the country, with a view to finding out the new drinks which make Americans feel at home.” The result, according to The New York Times: “Transatlantic wayfarers who happen to put up at [the Adlon] will find it hard to believe that they had left ‘God’s country.’”Footnote 71 The Esplanade soon created an American bar of its own, complete with a billiards table. The amenity was as much for the gratification of American visitors as it was a way of showing that the Esplanade was as up-to-date and cosmopolitan as the Adlon and other properties with American cocktail bars (Figure 2.3).

Figure 2.3 The American Bar in the grill room of the Esplanade, 1915

To draw American and British customers upstairs to the accommodations, hoteliers advertised the bathrooms. The Savoy promised facilities that were up to the standards of any expert “hygienist.” As early as 1897, the architect Carl Gause, who would later design the Adlon, had called for using American and British hotels as a model for inclusion of extra bathing amenities. The increase in visitors from Great Britain and the United States, he contended, necessitated an increase in the number of en suite rooms and apartments.Footnote 72 And so, in the next decade, new hotels such as the Fürstenhof emerged “after the American pattern,” with 300 rooms and 100 private bathrooms, “practical, comfortable, and hygienic.”Footnote 73 These measures contributed to the “commonplace” impression “that, from year to year, Berlin is becoming more American.”Footnote 74 For hoteliers, one of whom even established a New York office for the purpose of capturing potential guests before they set sail for Europe, Americanization meant greater profitability.Footnote 75

In the spring of 1909, Louis Adlon, son of Lorenz Adlon, founder of the eponymous hotel, traveled to the United States on a fact-finding mission. He recorded and broadcast his impressions in a long interview in The New York Times in May – an interview that outlined the complex relationship between the American and German hotel industries. In the article, he referred to American hotels as the “university in which European hotel keepers complete their education. Not all European hotel keepers … but the best, the most progressive, the most up-to-date.” He compared himself to “an American art student [traveling] to France to study art,” but in reverse. Adlon even credited Americans for a “small revolution in Continental hotel fashions.” Throughout the interview, Adlon praised the American hospitality industry even as he asserted Europe’s competitive edge.Footnote 76

If Louis Adlon went to Philadelphia, Washington, Chicago, and New York to understand what The New York Times referred to as the “fastidious American taste” in hotel design and amenities, he also did so to project his establishment’s readiness to please American visitors. “We have our own engine room, running water, [and] laundry,” Adlon boasted, plus “the American plan of bathrooms in individual rooms,” while many of Berlin’s hostelries “still lack[ed] some of these things.” American visitors to Berlin demanded all manner of niceties, which Adlon also promised: he planned to have grapefruit and terrapin imported, he would build en suite rooms throughout the hotel, he would supply in good order the American “characteristics of quick service, comfort, [and] intelligence.” The Adlon was “an up-to-date American hotel, even the café being modeled after the cafés in the best American hotels.”Footnote 77

In this rendering, the Adlon was at once German and not German, entrenched in Berlin society and politics, yet tethered to American culture and custom. Adlon took pains in the interview to distinguish European from American hotel culture. The Adlon and its European counterparts were more “homelike” than American hotels, which he saw as more spectacular and commercial. “When a man stops in an American hotel,” Adlon contended, “he retains all the time the feeling that he is stopping, not at home, but in a hotel – that he is buying the comforts that are showered upon him.” The Adlon family, on the other hand, tried harder to mask the exchange of money for hospitality: “We make friends of our patrons. That’s it. Here [in the United States] … you do not do that.” Adlon attributed the difference to the scale of American hotels and that country’s large hotel-dwelling population. Adlon was thus treading a fine line between presenting his establishment as Americanized and promising a good dose of old-world charm, care, and refinement. When he spoke of amenities, Adlon emphasized the American; when he spoke of hotel culture, he emphasized his staff’s personal touch.

Staff at the Adlon and Berlin’s other grand hotels were indeed impressive, especially for their command of foreign languages and customs, usually gained through work experience abroad.Footnote 78 Ludwig Müller, headwaiter at the Fürstenhof, had worked his way up the ranks as far away as Buenos Aires.Footnote 79 Andreas Nett (see Chapter 1) had served in four European countries before he applied to be a member of Müller’s staff.Footnote 80 Higher up the chain of command, hotel manager Alfred Jensen listed, in addition to his native Denmark, three other countries where he had found employ before 1914.Footnote 81 Restaurant and hotel manager Hubert Lyon had a similar résumé. With some hyperbole, one hotel’s promotional book described its head porter as being able to “speak Spanish like a Castilian, Italian like a Tuscan” and even a regional variety of French originating in Gascony, with its “friendly, whirring rrr.” Indeed, he “might [even] be said to muster a bit of Orientalia” when the situation required.Footnote 82 There existed a staff cosmopolitanism, that, in maintaining openness toward foreign languages, manners, and customs, made the cosmopolitanism of the elites easier to practice.

Republicans

Sometimes Berlin’s grand hotels brought people of different nationalities together, the better to show each other their differences. Hotels became key sites for Americans, especially, to make sense of their own ambivalence toward the German juggernaut, a foil for an imagined United States characterized by its lighter, brighter, more enlightened political culture and associational life. A superiority complex developed among Americans that sat uneasily with the mix of elite cosmopolitanism and German nationalisms on display at Berlin’s grand hotels on the eve of World War I.

The spectacle of German orderliness provided opportunities for American journalists to reckon with the apparent accomplishments of German civilization. “Berlin’s solid and orderly appearance” was impressive, “but isn’t everything forbidden?” a journalist asked in 1912 – “even blades of grass grow according to police regulations.” The theme of grass-cutting and authoritarianism returned in the summer of 1913, when the American critic James Huneker published a long piece on Berlin in The New York Times in which he served the city a series of backhanded compliments. Praise for the well-cropped grass in the median of Hardenbergstraße became a comment, again, on policing and the obedience characteristic of German subjects. Berlin’s police had “argus” eyes whose gaze “no one escapes.” The story’s headline, “The Kaiser’s Jubilee City,” identified the city as belonging to the emperor himself.Footnote 83

Yet, Berlin’s authoritarian and imperial spectacles were part of what drew Americans to the city in the first place. Huneker observed that “one of the chief ‘sights’ in the Tiergarten is the daily return of the Kaiser from Potsdam,” accompanied by a bugler who riffed on a Wagnerian theme. A review of the Guards Corps at Tempelhof field in September 1913, according to another New York Times correspondent, was “the great … social event of the year,” with Americans “as usual, much in evidence on the vast parade ground.” When in May of the same year Berlin hosted the king and queen of England and the czar of Russia at the same time, “countless exclamations of delighted enthusiasm in unmistakable transatlantic English broke forth” at the sight of the royal procession down Unter den Linden, past the Adlon and the Bristol. The Times correspondent approached this incident with some sense of irony: “A little royalty,” he conceded, might be “a dangerous thing for the patriotic sons and daughters of Uncle Sam.”Footnote 84 This royal procession was also greeted by US flags hanging from the balconies of Americans’ rooms at the Adlon, which transformed the colorscape of Unter den Linden into that of “Broadway or Michigan Boulevard,” The Times correspondent joked. These flags signaled support for the monarchs on parade while alerting them to the presence of true republicans in their land.

The Times liked to announce a metaphoric invasion, Americans having “taken possession of ‘Kaiserville.’” Indeed, “a look down the register of places like the Esplanade, Adlon, Bristol, or Kaiserhof” showed “an unending succession of New Yorks, Chicagos, Philadelphias, Bostons, San Franciscos, Wheelings, Leavenworths,” leaving the Germans “hopelessly in the minority alongside the tailor-made, broad-hatted women and the padded-shouldered, wide-trousered men, whose make-ups betray their nationality unmistakably.” Some of the wealthiest chose to sightsee by automobile, with small American flags affixed to the dashboards.Footnote 85 In this way, too, Americans used the flag to advertise their difference, their republicanism, adding a note of assertion to their ubiquity on the grand hotel scene.

The US holidays and commemorations occasioned more emphatic stagings of American exceptionalism. Since the 1890s, a small colony of American expatriates residing in Berlin had organized gatherings for Thanksgiving and the Fourth of July. In 1894, the grandest such event to date took place at the Kaiserhof, where the US ambassador, Theodore Runyon, delivered a Thanksgiving toast to the emperor’s health and then to the “great republic” across the sea. He spoke of being “proud of our birthright” – freedom from monarchy, one imagines – while in the same breath he thanked the German people for their hospitality and praised the host country for “its splendid literature, its advanced art and science, and its military renown” – not, of course, its political culture. The biggest Independence Day celebrations happened at Grünau, on the banks of the Spree. Most attendees of the picnics and games were Americans living in Berlin, but as The Times reported in 1914, the “crowd” of “five hundred patriots … was swelled during the day by the arrival of people, who came down from the hotels in automobiles or trains.” At the celebration two years prior, the American colony had arrived in full ostentation by steamboat in order to celebrate, on the Kaiser’s soil, the popular repudiation of monarchy and a heroic struggle against despotism.Footnote 86

Americans flaunted their republicanism most during US presidential elections, when they threw raucous election parties at Berlin’s grand hotels. The practice started as early as 1908 when the American ambassador and his staff decided to “camp out” on election night to await news by cable from The New York Times. The Adlon had agreed to display returns as they arrived on a large board in the lobby. This was perhaps the first election party held “for the benefit of the Americans resident in the Kaiser’s capital,” as The Times put it. Two hundred men and women congregated to wait and consume champagne, sandwiches, cigarettes, and coffee – all provided by the Adlon. In the small hours of the morning, when Taft’s victory seemed sure, “the assembly rose to its feet and broke into thunderous cheers.” The women led everyone in patriotic song to the accompaniment of the orchestra, engaged to play “Yankee melodies” all night. Four years later, several hundred people attended the party on election night, when Lorenz and Louis Adlon had the Marble Hall draped with American flags, under which, when the time came, there issued “a frenzied outburst of cheering and handclapping.” The orchestra, as before, played rags, marches, and other such “American compositions” until the party broke up after three o’clock in the morning. The Times had called the election for Woodrow Wilson.

When a New York Times correspondent wrote that “such scenes had never been witnessed in the memory of the oldest Berlin inhabitants,” he was broadly correct. Yes, these events were Berlin’s earliest American election parties, made possible by modern technologies of transoceanic telegraphy. At the same time, few Berliners would have recalled with clarity the last outburst of bourgeois enthusiasm for democracy: the Revolution of 1848.Footnote 87 Six and seven decades later, the election parties at the Adlon advertised the Americans’ particular success with republicanism where the Germans had failed. Indeed, the election parties were jingoistic spectacles that flaunted before Berliners the privileges and rights unavailable to them in this, Germany’s Second Reich. Ironically, the Americans’ republican chauvinism found a comfortable home in the Kaiser’s metropolis, itself famous, or notorious, for spectacular celebrations of national and imperial glory.

Hospitality of the Fortress

The composition of these conflicting interests fell apart quite suddenly. Britain declared war on Germany on August 4, 1914, in the bloody culmination of a month-long diplomatic crisis. That night, August 4/5, a mob attacked the British embassy in Berlin and then descended on the Adlon next door, where an emergency meeting of American and British tourists was taking place. The US ambassador James Gerard was in the process of assuring British nationals that their interests would be protected by the American embassy when three policemen, sabers drawn, entered the hall, seized New York Times correspondent Frederick William Wile, and dragged him into the lobby. Ambassador Gerard raised his voice in protest as the men hauled Wile into the main reception hall and out the front door. There, in front of the hotel, members of an angry mob beat him with fists and blunt objects before the police pushed him into a waiting car and whisked him away. Some minutes later, a German woman appeared at the reception desk to ask for Wile. The Adlon’s management had her arrested.Footnote 88

She and Wile were victims of spy fever, which was being fed by German newspapers as mobilizations mounted to the east and west of the German Empire. On July 31, 1914, Berliners had learned that Germany was now at war with Russia and the Reich lay under siege. The socialist organ Vorwärts wrote then of the “leaden presentiment of an approaching and nameless calamity weigh[ing] upon the great multitude of those who wait for the latest news.”Footnote 89 The announcement of Germany’s mobilization on the following day, August 1, triggered a panic. With little to print in the way of details, editors opted for bogus stories of espionage against the fatherland – for example, that the country had been infiltrated primarily by Russians and their agents on the hunt for information and for ways to sabotage the fledgling mobilization. At the same time, hundreds, if not thousands, of people responded to government warnings that the French were secretly transporting gold in automobiles from France to Russia, across German soil, to finance the two-front war. In the first week of international hostilities, twenty-eight German motorists died from shots fired into their cars by excited patrolmen.Footnote 90

Meanwhile, as German armies invaded Luxembourg, Belgium, and then France, many of the Reich’s borderlands turned into war zones. The rest were sealed. Ship berths sold out and travel by sea became perilous as Britain and then Germany declared naval blockades. But to stay put could be just as dangerous. Many foreign nationals – British, French, Russian, Belgian – lost consular representation in Germany and thus had to rely on the goodwill of other missions. Most travelers had no state-issued identification, to say nothing of passports. These conditions left thousands of hotel guests in Berlin at risk of being apprehended as suspected spies.

Soon, spy fever infected the Adlon’s staff. Charles Tower, correspondent for the Daily News (London) was denounced by a chauffeur and arrested.Footnote 91 The following week, New Yorker John Davis was apprehended on the basis of a statement by a maid.Footnote 92 The porter, not the manager or a member of his staff, accompanied a police officer, his gun drawn, to Davis’s room. The snooping maid, the call to the police, the absence of management, the drawn gun – all point to a breach in hotel decorum and a disturbance of hierarchy. Adlon staff members – in similar cases, also management – implicated themselves in a contest between a nativist mob and privileged tourists.

Conclusion

During the war, the Adlon and other grand hotels would become increasingly penetrable by outside demands, their hierarchies increasingly susceptible to internal instability. These vulnerabilities, latent in the prewar arrangement, burst forth at the first signs of external crisis. Huneker, in his 1913 critique of the capital, hinted at this latency. His discussion conjured two unstable balances: one, between nationalist and cosmopolitan imperatives; and the other, between guests and staff, in other words, between the social group that was granted liberal subjectivity and the social group that was denied it. “At times,” Huneker felt “as if I was sitting over a big boiler that is carrying too much steam. If an explosion ever comes it will be felt the world over.”Footnote 93 The explosion came in summer 1914 and rocked Berlin’s grand hotels right away. It was the abrupt end to a relative golden age in grand hotel society – an age in which cosmopolitanism, nationalism, and the classes had coexisted in a delicate balance.

While the inciting incident came from outside, fatal flaws lay within. The staff hierarchies undergirding the cosmopolitanism of the elites buckled as cosmopolitanism itself became anathema to German society’s new purpose. The war between empires buried the privileged cosmopolitanism and everyday liberalism of the grand hotel – the sense that elites could be trusted to behave and that workers could be pressured to cooperate – under a mountain of new, destructive imperatives: the imperatives of the fortress.