Introduction

Genebanks traditionally supply crop diversity to support plant breeding in formal seed systems comprising of agricultural research organizations and seed companies. In Africa, however, formal seed systems are weak and smallholder farmers get more than 80% of their seeds from local seed systems (Louwaars and De Boef, Reference Louwaars and De Boef2012; McGuire and Sperling, Reference McGuire and Sperling2016). To enhance utilization of crop diversity in Africa, genebanks have started to experiment collaborating directly with farmer groups in on-farm evaluation for direct use (Westengen et al., Reference Westengen, Skarbø, Mulesa and Berg2018).

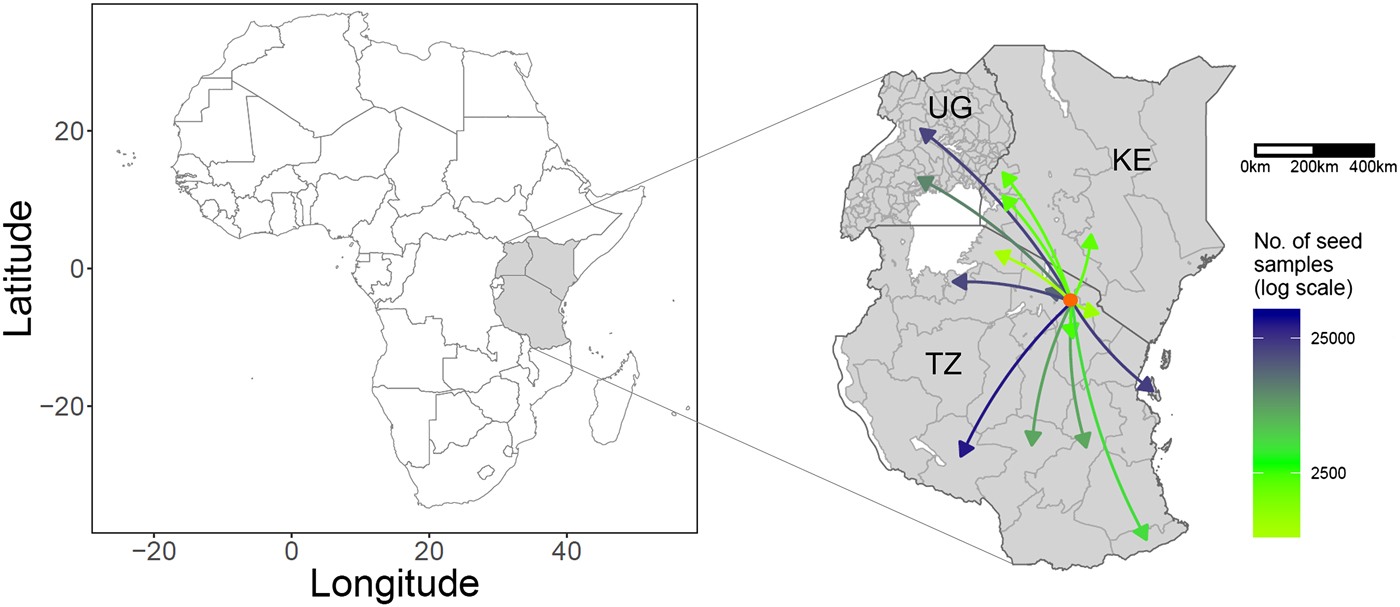

This paper provides the example of the World Vegetable Center (WorldVeg) genebank of traditional African vegetables. This genebank has distributed over 42,514 seed kits with a total of 183,193 seed samples to smallholder farmers in Tanzania, Kenya and Uganda between 2013 and 2017 (Fig. 1; Table 1; online Supplementary Table S1).

Fig. 1. Distribution of seed samples to farmers in Tanzania (TZ), Kenya (KE) and Uganda (UG) in East Africa. The orange spot is the location of the WorldVeg genebank of traditional African vegetables in Arusha, Tanzania.

Table 1. Distribution of seed samples per species and country

The seed kits that farmers received contained on average four seed samples of different vegetable crops or varieties, usually enough to plant in a home garden (online Supplementary Fig. S1). Seed kits included lines of traditional African vegetables, WorldVeg tomato lines and in some cases Capsicum pepper and soybean lines (Table 1). The full dataset is available at https://www.gbif.org/dataset/b5d15a8b-0500-4d8b-b156-9da14da494cc. Thirty-two per cent of the seed distributed came from promising accessions and 68% from breeding lines; all are maintained by the WorldVeg genebank.

The WorldVeg genebank of traditional African vegetables

The genebank currently has 2500 accessions of mostly traditional African vegetables, and conserves, screens and distributes this germplasm. The collection originated from germplasm-collecting missions with national partners across Africa, mostly in the early 2000s. Other accessions came from the WorldVeg genebank in Taiwan.

Seed kit distribution

The WorldVeg genebank of traditional African vegetables has distributed seed kits in East Africa since the early 2000s, systematic recording started in 2013. The following facts are important about the seed distribution:

First, accessions and breeding lines selected for the vegetable seed kits were tested under local conditions for yield, disease resistance and consumer preference.

Second, distributed lines were open-pollinated so that farmers could save seed.

Third, seed was distributed through international NGOs, farmer groups, local governments and WorldVeg projects (online Supplementary Table S2). Seed kit distribution was not intended as emergency seed aid, but was part of home garden projects aimed at improving nutrition and diversifying incomes.

Fourth, seed kits were distributed in combination with capacity development in vegetable growing and seed saving. Seed kits contained instructions of good agricultural practices and the nutritional values of the concerning crops. WorldVeg collects feedback from farmers about the seed kits supplied in certain projects but not all. Some impact studies on home garden interventions have been published (e.g. Schreinemachers et al., Reference Schreinemachers, Brown, Roothaert, Makamto Sobgui and Toure2018).

Fifth, these were one-time distributions of seed kits, so households did not receive a regular supply of seed that might create dependency or crowd-out local seed enterprises (McGuire and Sperling, Reference McGuire and Sperling2016).

Discussion

Our seed kit example shows how new partnerships between genebanks and public, private and societal partners allow to supply many smallholder farmers with crop genetic diversity. We identified four research questions to better understand the role and impact of seed kit distribution on seed systems, local vegetable diversity, nutrition and production.

First, what is the role of seed kit distribution in strengthening local seed systems of vegetables? Seed exchange between recipients of seed kits and non-recipients can multiply the effect of seed kits and contribute to large-scale diversification of seed supply (Coomes et al., Reference Coomes, McGuire, Garine, Caillon, McKey, Demeulenaere, Jarvis, Aistara, Barnaud, Clouvel, Emperaire, Louafi, Martin, Massol, Pautasso, Violon and Wencélius2015). Tracing seeds and mapping seed networks will provide a better understanding of the effectiveness of seed kit distribution to strengthen local seed systems. Collaboration with farmer groups and national agricultural institutions ensures that further steps in seed system development, breeding and seed production are in line with farmer interests and national seed policies.

Second, what is the impact of seed kit distribution on local vegetable diversity? While replacement of existing landraces could lead to genetic erosion, introduction of new germplasm may enhance levels of local vegetable diversity.

Third, how many people improve their nutrition after seed kit distribution and strengthened seed systems? Seed kit and home garden interventions effectively help poor rural households to improve their nutrition, generate income and enhance gender equality within households (Berti et al., Reference Berti, Krasevec and FitzGerald2004; Schreinemachers et al., Reference Schreinemachers, Patalagsa and Uddin2016). It is less clear how seed kits can foster nutritional outcomes at the level of communities and food systems.

Finally, how does farmers′ use of seed kits help adapt farming systems to the negative effects of global climate change? Vegetable seed kits may introduce new crops and new varieties adapted to changing climates and with potential to diversify farming systems for income and yield stability under climate change (van Etten et al., Reference Van Etten, Beza, Calderer, Van Duijvendijk, Fadda, Fantahun, Kidane, Van De Gevel, Gupta, Mengistu, Kiambi, Mathur, Mercado, Mittra, Mollel, Rosas, Steinke, Suchini and Zimmerer2016). Seed kit distribution with climate-resilient vegetables for on-farm evaluation combined with remote sensing of changes in farmers' crop portfolio can help to understand the effectiveness of seed kits to promote variety and crop adoption.

Currently, seed kit development and distribution is financed by development projects. The production of a vegetable seed kit with four seed samples costs about US$5 to produce, excluding distribution costs. To make seed kits more attractive, the production costs can be decreased by focusing on fewer crops or by working with local seed companies that have specialized capacity to produce seed kits. WorldVeg has recently started to charge up to 10% of the cost price of seed kits to farmers to increase farmers’ contribution in future, considering that farmers in African countries are willing to invest in seed (McGuire and Sperling, Reference McGuire and Sperling2016). This paves the way for commercialization of seed kits by local seed companies.

As formal seed systems expand their reach, the genebank's role to supply vegetable diversity to public and private breeding programmes becomes more important. This trend takes place in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda where seed companies have started to sell seeds of traditional African vegetables. To optimize supply of vegetable diversity, the WorldVeg genebank of traditional African vegetables continues working with partners in both formal and local seed systems.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1479262119000017

Acknowledgements

We thank Australian AID, Helen Keller International, HORTCRISP (Innovation Lab), USAID, OIKOS, CABI, CGIAR Humidtropics programme, Southwood Lutheran church, Project Concern International and the Sustainable Forum Alliance Francais for their support in seed kit distribution. Publication of this paper and development of the corresponding dataset was funded by the European Union, and supported by GBIF and the BID project: BID-AF2017-0310-SMA. Funding for WorldVeg's general research activities is provided by core donors: Republic of China (Taiwan), UK aid from UK government, United States Agency for International Development (USAID), Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR), the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development of Germany, Thailand, Philippines, Korea and Japan. Special thanks to Walter de Boef for his valuable comments on an early draft of the paper.