Introduction

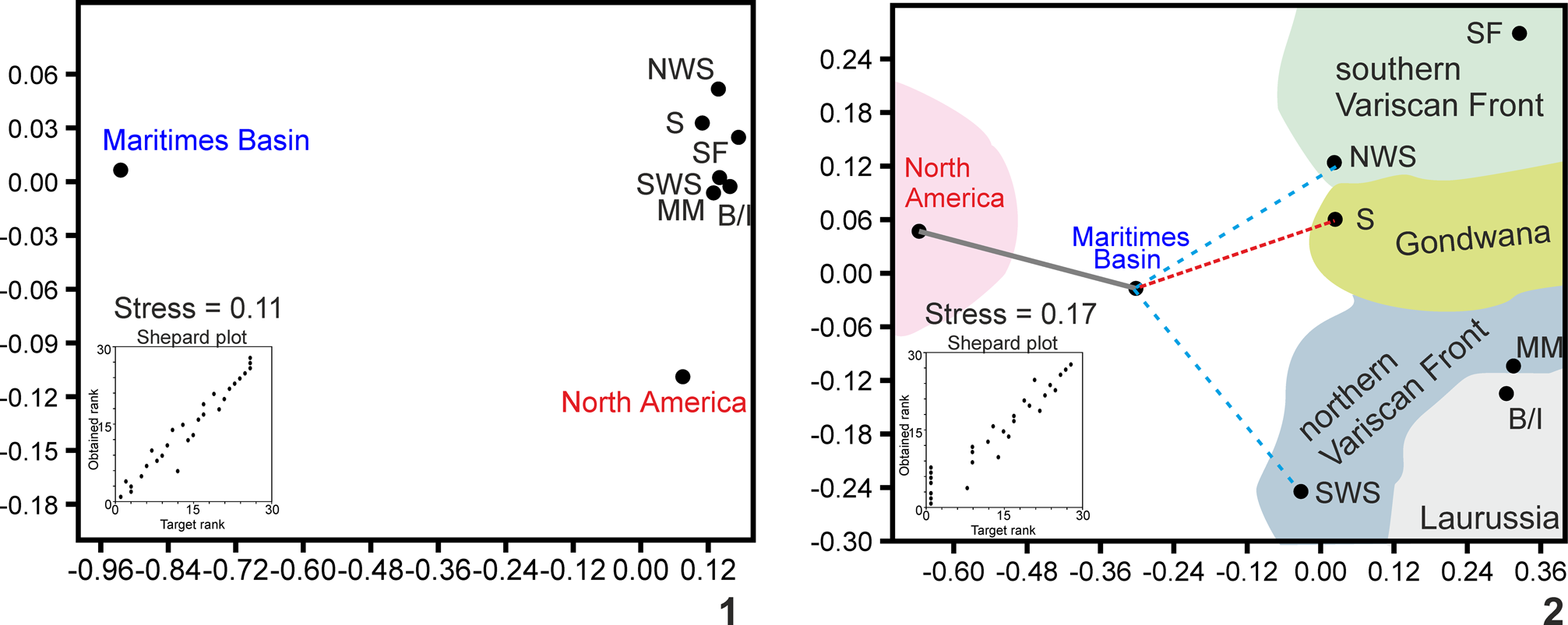

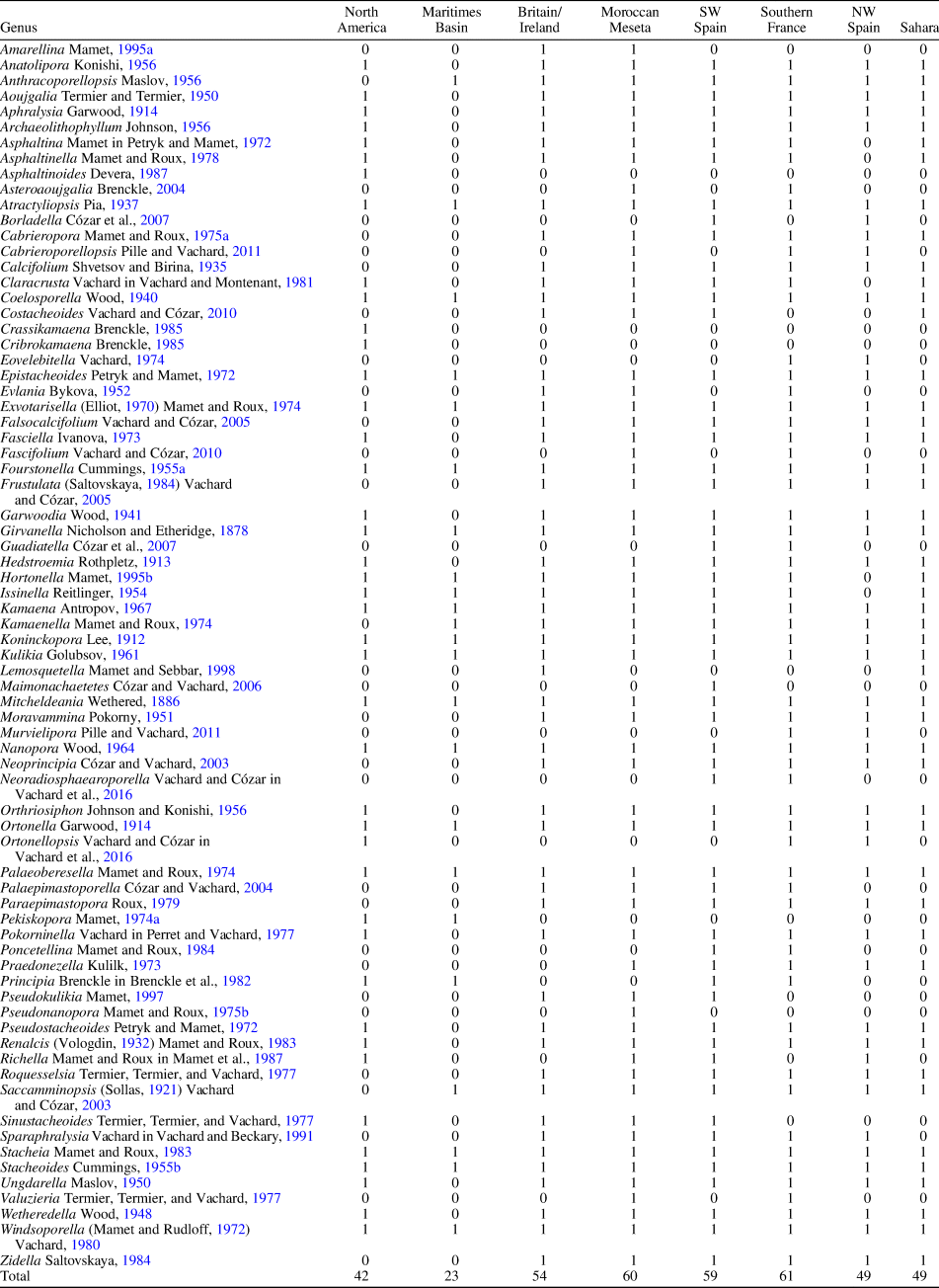

The Maritimes Basin of Atlantic Canada comprises Middle Devonian to early Permian strata (Gibling et al., Reference Gibling, Culshaw, Pascucci, Waldron, Rygel and Miall2019) and includes SW Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick (Fig. 1). Its underlying substrata are composed of a series of amalgamated terranes of peri-Gondwanan affinity that drifted from Gondwana during Ordovician times (e.g., Waldron et al., Reference Waldron, Barr, Park and White2015; Gibling et al., Reference Gibling, Culshaw, Pascucci, Waldron, Rygel and Miall2019) or even from the Proterozoic/early Cambrian (e.g., Landing, Reference Landing2005). By the Middle Devonian, these terranes were supposedly attached to the North American craton (e.g., van Staal et al., Reference van Staal, Dewey, MacNiocaill, McKerrow, Blundell and Scott1998; Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Fernández-Suárez, Keppie and Jeffries2004). This episode is related to the closure of the Rheic Ocean (Fig. 2) that started in the Early Devonian and by the early Carboniferous was considered according to some authors essentially closed (e.g., Nance et al., Reference Nance, Gutiérrez-Alonso, Keppie, Linnemann, Murphy, Quesada, Strachan and Woodcock2012, and references therein). McKerrow et al. (Reference McKerrow, MacNiocaill, Ahlberg, Clayton, Cleal, Eager, Franke, Haak, Oncken and Tanner2000) considered that the Rheic Ocean was open during the Devonian and the collision occurred during the early Carboniferous. During the Devonian, the ocean was not wide enough to prevent the migration of key fauna. A similar scenario was adopted by Torsvik and Cocks (Reference Torsvik and Cocks2004, Reference Torsvik and Cocks2013), although they considered the relatively narrow Rheic Ocean was located northward of Armorica. South of Armorica, Torsvik and Cocks (Reference Torsvik and Cocks2004, Reference Torsvik and Cocks2013) interpreted a wide Paleotethys Ocean, with Gondwanaland displaced to a more southerly position. Since the Middle Devonian, Stampfli and Borel (Reference Stampfli and Borel2002) only considered a vast Paleotethys Ocean to the south, and the Rhenohercynian Ocean to the north, separated by the macro-European Hunic terrane. In contrast, Stampfli et al. (Reference Stampfli, Hochard, Verard, Wilhem and von Raumer2013) considered a wide Rheic Ocean during the Frasnian and Famennian (Upper Devonian) between the Meguma/Avalonia terranes and the newly formed continent (Laurussia). Stampfli et al. (Reference Stampfli, Hochard, Verard, Wilhem and von Raumer2013) considered that closure of the Rheic Ocean occurred during the Tournaisian, coincident with opening of the Paleotethys Ocean to the south.

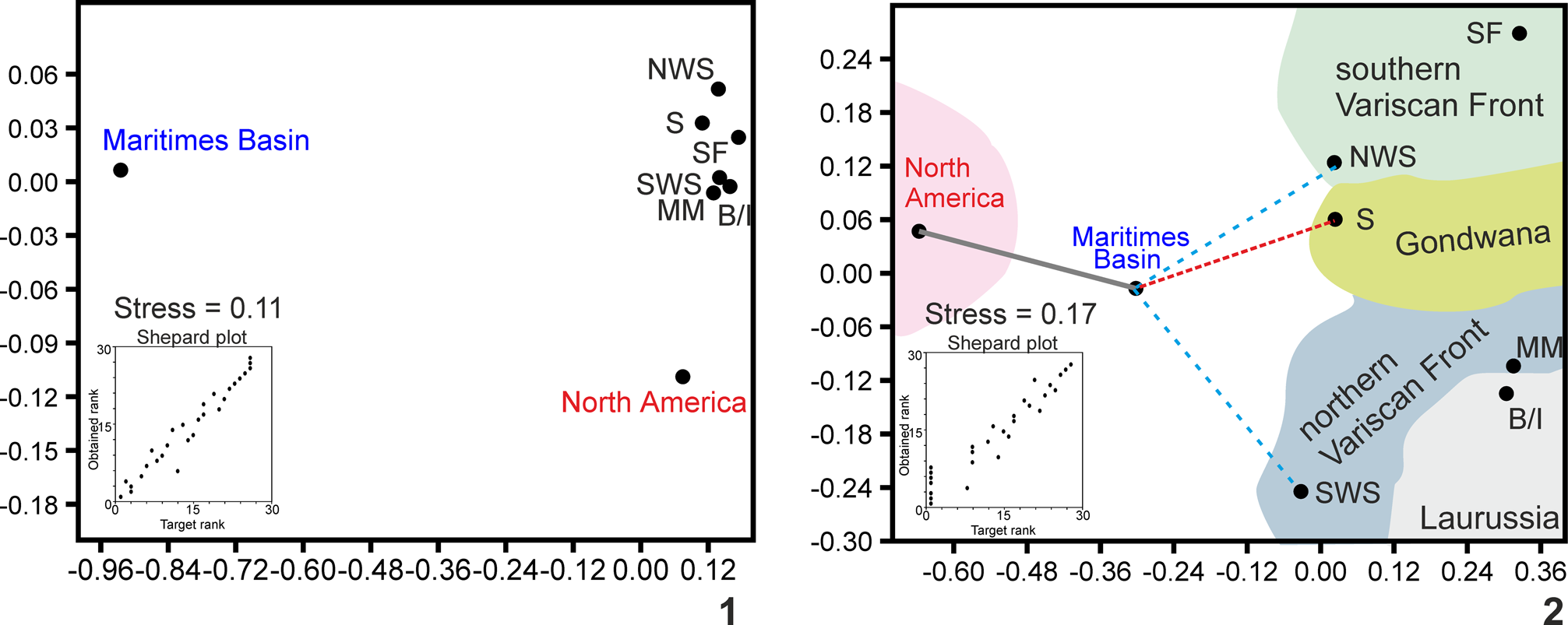

Figure 1. The Maritimes Basin of Atlantic Canada (shaded). Inset map shows location of the Maritimes Basin in North American craton and other regions/basins cited in the text. 1 = Alaska; 2 = Alberta (Western Cordillera); 3 = Mid-Continent; 4 = Appalachians.

Figure 2. Late Viséan-Serpukhovian paleogeography and paleobiogeography (modified from 340-325 Ma map of Blakey, Reference Blakey2013).

It must be taken into consideration that tectonic models developed for the Maritimes Basin by North American researchers are usually related to the Alleghenian orogeny, and that this zone is typically compared with the Appalachian style (e.g., Waldron et al., Reference Waldron, Barr, Park and White2015; Gibling et al., Reference Gibling, Culshaw, Pascucci, Waldron, Rygel and Miall2019). This is illustrated by the postulated collision of the terranes with the North American part of Laurussia during Devonian times. Eastern Appalachian tectonic units have been correlated with those in Britain and Ireland, suggesting a pre-collision (Devonian) separation of ~800 km between Newfoundland and Ireland (Waldron et al., Reference Waldron, Schofield and Murphy2018).

Facies and tectonic models reflecting similarities between Mississippian rocks in Ireland and the Maritimes Basin were first claimed by Belt (Reference Belt1929, Reference Belt1944, Reference Belt1969), and the first faunal arguments corroborating this hypothesis based on rugose corals were published contemporaneously (Lewis, Reference Lewis1935). Nevertheless, the general paleogeographic models disagree, and the idea has not been unanimously accepted by all authors who have studied the diverse fauna and microflora. These later authors supported the hypothesis that the Maritimes Basin was closer to the American Appalachians than to Europe (e.g., Globensky, Reference Globensky1967; Mamet, Reference Mamet1968, Reference Mamet1970; Jansa and Mamet, Reference Jansa and Mamet1984). Other authors have progressively revealed new data that disagree with this distant paleogeographic position for the Maritimes Basin and Europe, showing additional sedimentological similarities between the Maritimes Basin and Ireland/Britain (Giles, Reference Giles1981, Reference Giles2009; Mitchell, Reference Mitchell1992; von Bitter et al., Reference von Bitter, Giles and Utting2007). Transgressive-regressive events have been recognized in the Visean Windsor Group (e.g., Giles, Reference Giles1981, Reference Giles2009; Fig. 3), which were compared with the major cycles defined in northern England by Ramsbottom (Reference Ramsbottom1973). Mitchell (Reference Mitchell1992) showed unconformities with similar timing and duration, and similar fault control for basin initiation and subsidence, and thus, stratigraphic similarities between the Maritimes Basin and Northern Ireland. All of those previous studies, as well as some faunal and floral similarities, were summarized by von Bitter et al. (Reference von Bitter, Giles and Utting2007).

Figure 3. Simplified stratigraphic succession for the Windsor Group in Nova Scotia. Biostratigraphic age determinations: shaded column from Jutras et al. (Reference Jutras, McLeod and Utting2015); white column according to von Bitter et al. (Reference von Bitter, Giles and Utting2007). Cycles 1-5 as defined by Giles (Reference Giles1981). Fm = Formation.

Giles (Reference Giles1981) described five cycles in the Windsor Group (A−E or 1−5 auct.; Fig. 3), of which cycles 2−5 show similarities with the cycles defined in the Asbian-Brigantian of Ireland and northern England (von Bitter et al., Reference von Bitter, Giles and Utting2007). However, cyclic sedimentation interpreted as glacioeustatic-driven transgressive-regressive sequences for the late Visean and Serpukhovian, as shown in detail by Giles (Reference Giles2009), are not exclusive to Ireland and England (Yoredale cyclothems) being common in Belgium/northern France (e.g., Hance et al., Reference Hance, Poty and Devuyst2001), the North American Midcontinent (e.g., Smith and Read, Reference Smith and Read2000), and even in Saharan basins of the Gondwana platform (e.g., Bourque et al., Reference Bourque, Madi and Mamet1995; Cózar et al., Reference Cózar, García-Frank, Somerville, Vachard, Rodríguez, Medina-Varea and Said2014, Reference Cózar, Somerville, Vachard, Coronado, García-Frank, Medina-Varea, Said, del Moral and Rodríguez2016b).

Faunal and floral similarities between the Maritimes Basin and Ireland/Britain have been highlighted in previous publications (von Bitter, Reference von Bitter1976; von Bitter and Plint-Geberl, Reference von Bitter and Plint-Geberls1982; Clayton, Reference Clayton1985; Utting, Reference Utting1987; Purnell and von Bitter, Reference Purnell and von Bitter1992; Poty, Reference Poty, Hicks, Henderson and Bamber2002; Utting and Giles, Reference Utting and Giles2004; von Bitter and Legrand-Blain, Reference von Bitter and Legrand-Blain2007). Most data are based on rugose corals, conodonts, brachiopods, and miospores.

This study is primarily focused on two groups of microfossils: foraminifers and calcareous algae (including problematic algae). Both groups are widespread in most carbonate platform facies during the Mississippian and are distributed over a vast geographic area suitable for paleobiogeographic comparisons. The aim of this study is to highlight species of foraminifers and calcareous algae that are recorded in western Europe/northern Africa and the Maritimes Basin, and those recorded in the North American Realm, whose migration routes might have passed through the Maritimes Basin.

Material and methods

A revision of individual foraminiferal/algal taxa is included for which plausible paleobiogeographical affinities are discussed. This section is based purely on the presence/absence of different taxa in the Maritimes Basin as well as in other basins in Europe, North Africa, or North America.

To compare the paleobiogeography of the Maritimes Basin, foraminifers (excluding unilocular genera) and algae (including problematic algae) of the late Visean and Serpukhovian were selected from the following regions: Midcontinent/Appalachians, Britain/Ireland, SW Spain (including basins in the northern Ossa-Morena and southern Central Iberian zones), Moroccan Meseta (mostly western Meseta), NW Spain (Cantabrian Mountains), southern France (including Montagne Noire, Mouthoumet, and Pyrenees), and the Saharan basins of Morocco and Algeria (including the Tindouf and Béchar basins). The database from the Maritimes Basin is mostly based on Mamet (Reference Mamet1968, Reference Mamet1970), Brisebois (Reference Brisebois1979), Jansa and Mamet, (Reference Jansa and Mamet1984), Poty (Reference Poty, Hicks, Henderson and Bamber2002), and von Bitter and Legrand-Blain (Reference von Bitter and Legrand-Blain2007) (see Tables 1, 2).

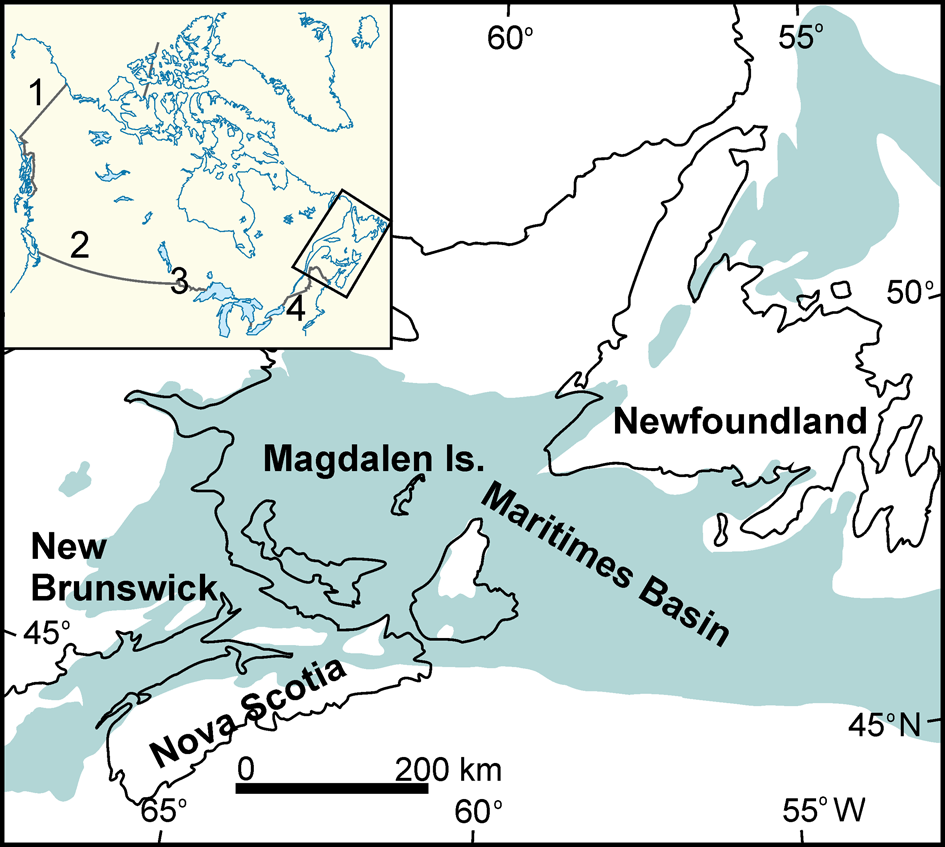

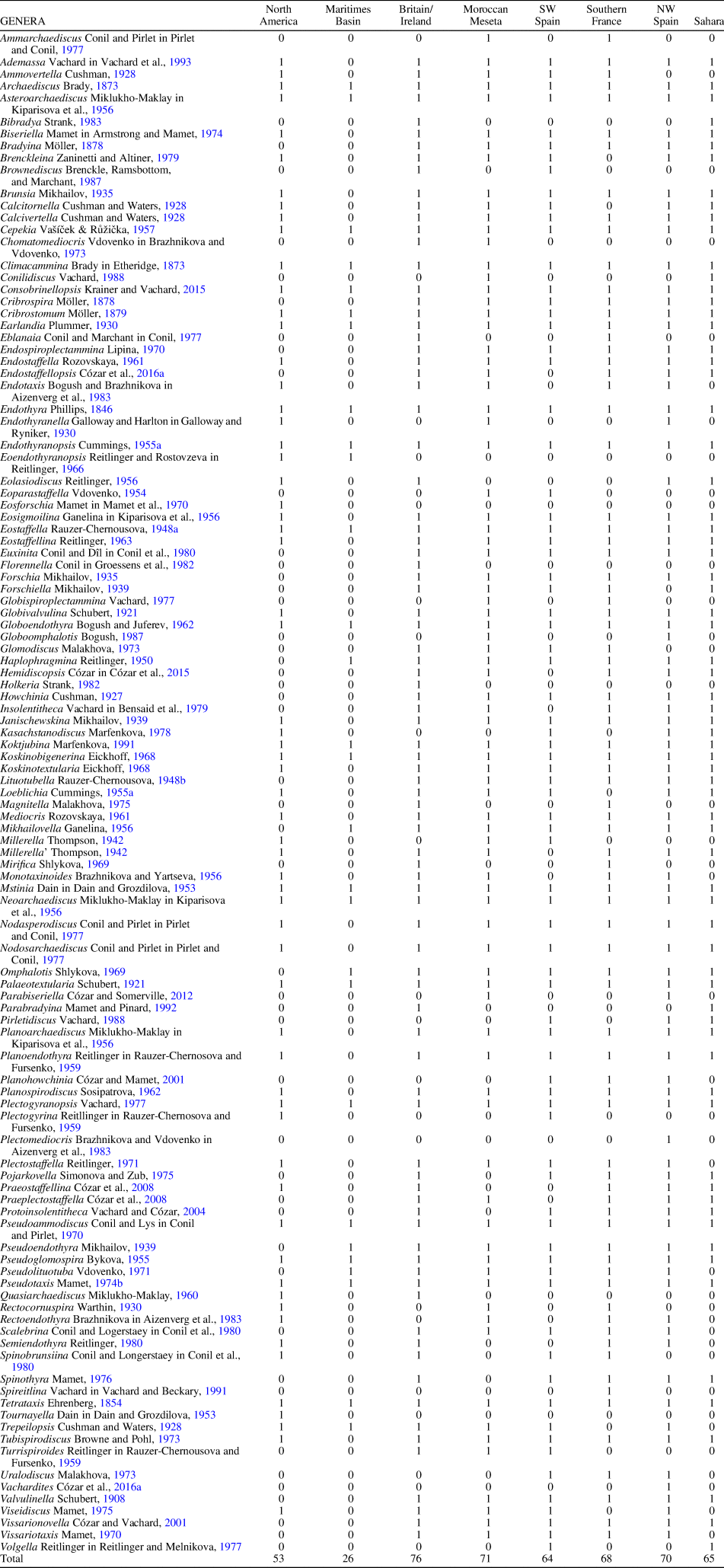

Table 1. Revised late Visean-Serpukhovian algae and problematic algae from the Maritimes Basin, Midcontinent/Appalachian, and western Paleotethys. 0 = absent; 1 = present.

Table 2. Revised late Visean-Serpukhovian foraminifers from the Maritimes Basin, Midcontinent/Appalachian, and western Paleotethys (unilocular genera excluded). 0 = absent; 1 = present.

To avoid a long list of publications, recent studies that have previously compiled taxonomic databases are preferred herein, and thus the database on foraminifers contains 110 genera based on Davydov and Cózar (Reference Davydov and Cózar2019, and references therein). The database on algae contains 74 genera compiled from Mamet (Reference Mamet and Riding1991, Reference Mamet1992, Reference Mamet1995b, Reference Mamet, Hills, Henderson and Bamber2002), Cózar and Vachard (Reference Cózar and Vachard2003, Reference Cózar and Vachard2005), Pille (Reference Pille2008), Vachard and Cózar (Reference Vachard and Cózar2010), and Vachard et al. (Reference Vachard, Cózar, Aretz and Izart2016).

A binary presence/absence database was analyzed using the PAST v.3.14 software (Hammer, Reference Hammer2016). The Jaccard and Raup and Crick similarity indices were calculated in the cluster using paired linkage (UPGMA). Nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) was also applied to graphically express the similarity indices among the regions. The Raup-Crick coefficient was used because it minimizes the result of overweighting widely distributed species and is less affected by sampling bias (Raup and Crick, Reference Raup and Crick1979). The database was analyzed at the generic level, because (as demonstrated by Cózar et al., Reference Cózar, Somerville, Blanco-Ferrera and Sanz-López2018 and Davydov and Cózar, Reference Davydov and Cózar2019) there was no significant difference with the analysis at the specific level, and it prevents more frequent contradictory interpretations resulting from the species comparison due to more uneven data.

Repositories and institutional abbreviations

The algal and foraminiferal collections of thin sections used for the statistical analysis are deposited in the following institutions: Royal Ontario Museum, Canada (studies by P. von Bitter); National Museum of Natural History, Washington DC, USA (studies by R.G. Browne, D.E. N. Zeller, and M. Rich); University of Colorado Museum, Boulder, USA (studies by P. Brenckle; part of the collection from northern Arkansas is still in the possession of the author); Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique, Brussels (part of the studies after 2000 by B.L. Mamet); Université de Liège, Belgium (studies by R. Conil and M. Laloux); Université Paul-Sabatier, Toulouse, France (studies by L. Pille); Université de Lille 1, France (studies by D. Vachard); British Geological Survey, Keyworth, UK (studies by I. Burgess and by A.R.E. Strank, C.N. Waters, I. Burgess, and P. Cózar from boreholes in northern England); British Geological Survey, Edinburgh, UK (studies by P. Cózar from boreholes in the Midland Valley of Scotland); University College Dublin, Ireland (studies by I.D. Somerville and S. Gallagher); Université Moulay Ismail, Meknès, Morocco (studies by M. Berkhli); Institute Scientifique de Rabat, Morocco (studies by A. Tahiri); Université Cadi Ayyad, Marrakech, Morocco (studied by A. Tourani); Paleontological Collection, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Spain (studies by P. Cózar = PC). The collection of M.-F. Perret is lost (personal communication, M.-F. Perret, 2015). The repository of B. Mamet's pre-2000 samples referred to in this study is unknown (personal communication, A. Préat, 2021).

Algae and problematic algae

A detailed revision of the Carboniferous calcareous algae was published by Mamet (Reference Mamet and Riding1991), with the main paleobiogeographic aspects more extensively developed by Mamet (Reference Mamet1992). These studies summarized knowledge of the calcareous algae in the twentieth century and include a vast paleobiogeographic and biostratigraphic database. However, as Mamet (Reference Mamet and Riding1991) recognized, the algal nature of numerous taxa used in his paleobiogeographic analysis is rather questionable (e.g., Cylindrofolia Brenckle and Groves, Reference Brenckle and Groves1987, and Eolithoporella Johnson, Reference Johnson1966). He recognized 135 valid genera with 276 species distributed in three major realms (Fig. 2)—North America, Paleotethys, and Arctic (= Boreal)—subdivided into eight subrealms. Approximately half of the calcareous algae were considered cosmopolitan (49 genera) or of generalized dispersion (16 genera), but more important for the paleobiogeographic studies, are the endemic taxa to these three realms. The Paleotethys is the most diverse realm containing up to 38 endemic genera.

The geographic distribution of several genera has been updated since Mamet's (Reference Mamet and Riding1991, Reference Mamet1992) database, resulting in modification of the distribution of some taxa. Mamet (Reference Mamet1968, Reference Mamet1970) and mostly Jansa et al. (Reference Jansa, Mamet and Roux1978) identified a total of 31 taxa from different localities in the Maritimes Basin, of which Windsoporella (Mamet and Rudloff, Reference Mamet and Rudloff1972) Vachard, Reference Vachard1980 and Pekiskopora Mamet, Reference Mamet1974c were considered endemic to the North American Realm, with the rest of the assemblages as cosmopolitan or of generalized distribution. Similar taxa were also recorded by Brisebois (Reference Brisebois1979). The diversity and richness of algae in the Maritimes Basin are difficult to assess because: (1) the possible influence of deep oceans and cold water platforms/currents that did not permit a widespread settlement of the dasycladales (Jansa and Mamet, Reference Jansa and Mamet1984); (2) limited documentation of these algal assemblages available in only a few publications, even in the absence of illustrations; and (3) variable but often-poor preservation in most of the carbonates in the Windsor Group of Nova Scotia and Codroy Group of Newfoundland, which are often dolomitized or composed of evaporites (Mamet, Reference Mamet1970; Jansa et al., Reference Jansa, Mamet and Roux1978).

Windsoporella was originally considered as an algal genus endemic to the North American Realm, but has been recorded, rarely, in the eastern Paleotethys realm (Vachard, Reference Vachard1980) and subsequently commonly recorded in western European/northern African basins (see revision of the genus Windsoporella by Cózar et al., Reference Cózar, Vachard, Somerville, Pille and Medina-Varea2009; Pille and Vachard, Reference Pille and Vachard2011).

Jansa et al. (Reference Jansa, Mamet and Roux1978) illustrated Pekiskopora sp. (endemic to the North American realm), although it cannot be unquestionably attributed to that genus because of its poor preservation. In those specimens, only the outer morphology is preserved, a feature that does not allow a reliable identification of Pekiskopora, and in general, of any dasycladal algae. Furthermore, the outer morphology is rather like that of other coeval dasycladal algae, e.g., Kulikia Golubsov, Reference Golubtsov1961. Pekiskopora was also documented (but not illustrated) by Brisebois (Reference Brisebois1979) in limestones of Brigantian age on the Magdalen Islands in the central Gulf of St. Lawrence (Fig. 1). Although the identification cannot be confirmed at either of these widely separated localities in the Maritimes Basin, its reported presence continues to signal an American connection.

Additional remarks on the algal assemblages need to be highlighted. First, the Maritimes Basin is notable for the occurrence of Kamaenella Mamet and Roux, Reference Mamet and Roux1974, a typical Western Paleotethyan genus that does not occur in other regions of North America. Kamaenella thickets are common in many upper Visean platforms from Ireland and England (Gallagher, Reference Gallagher, Strogen, Somerville and Jones1996; Horbury and Adams, Reference Horbury, Adams, Strogen, Somerville and Jones1996; Cózar and Somerville, Reference Cózar and Somerville2005b). Nevertheless, quantification of the calcareous algae listed by Jansa et al. (Reference Jansa, Mamet and Roux1978) was not documented, and thus, it is not possible to precisely establish whether it contributes to similar thickets. Second is the occurrence (although rare) of Saccamminopsis (Sollas, Reference Sollas1921) Vachard and Cózar, Reference Vachard and Cózar2003 in the Maritimes Basin. This problematic alga was attributed to the Udoteacea algal reproductive organs by Vachard and Cózar (Reference Vachard and Cózar2003), although it was previously attributed to the dasycladal algae (Skompski, Reference Skompski1986), and recorded only in the Paleotethys realm (see distribution of Vachard and Cózar, Reference Vachard and Cózar2003). In Ireland and northern England, this taxon commonly occurs as ‘floods,’ i.e., rich concentrations in bands in upper Visean limestones (e.g., Hallett, Reference Hallett1971; Gallagher and Somerville, Reference Gallagher and Somerville1997; Cózar and Somerville, Reference Cózar and Somerville2005b). Its occurrence in the Maritimes Basin has never been documented as flood-like deposits, but its occurrence ‘outside’ of the Paleotethys realm is significant enough by itself. Third is the presence of the problematic alga Anthracoporellopsis Maslov, Reference Maslov1956, a taxon reported by both Jansa et al. (Reference Jansa, Mamet and Roux1978) and Brisebois (Reference Brisebois1979), and restricted to the Paleotethys realm and the Canadian Arctic (Vachard and Cózar, Reference Vachard and Cózar2010).

As a consequence of the above data, the assemblages of the Maritimes Basin do not contain unquestionable algal or problematic algal genera endemic to the North American Realm in the assemblages of the Maritimes Basin, because the identification of Pekiskopora could not be confirmed and the recrystallized specimens are more similar to the outer morphology of Kulikia (a cosmopolitan taxon). In addition, Pekiskopora is recorded only in the Tournaisian, and thus its occurrence in the late Visean of the Maritimes Basin seems implausible. In contrast, there are at least three typical Paleotethyan genera present: Kamaenella, Saccamminopsis, and Anthracoporellopsis.

Another significant algal taxon for paleobiogeographic interpretations is Albertaporella Johnson, Reference Johnson1966, described as an early Visean endemic genus in the North American Cordillera (Johnson, Reference Johnson1966; Mamet, Reference Mamet and Riding1991) and New Mexico (Armstrong et al., Reference Armstrong, Mamet and Repetski1992); it has also been recorded in the early Visean of SE Ireland (Cózar and Somerville, Reference Cózar and Somerville2005a). The most logical explanation is that the taxon migrated via the Rheic corridor (Fig. 2), because there is no record of Albertaporella in the Arctic realm (Mamet and Preat, Reference Mamet2010), and thus, migration by the Franklinian corridor in the Boreal Ocean is discarded (Fig. 2). The apparent absence of Albertaporella in the Maritimes Basin can be explained by the absence of more diverse and richer assemblages due to limited documentation to date, but also because the presence of early Visean strata in the Windsor Group is still debated; if present, these are mostly composed of thick evaporite deposits in cycle 1 (e.g., Jutras et al., Reference Jutras, McLeod and Utting2015; Waldron et al., Reference Waldron, Giles and Thomas2017; Fig. 3) that would themselves have formed an unfavorable environment.

Foraminifers

Despite the presence of numerous endemic genera, a clear exclusively worldwide provincialism does not seem to have existed within the Mississippian Fusulinata foraminifers. Mamet and Skipp (Reference Mamet and Skipp1970a) and Mamet (Reference Mamet, Kauffman and Hazel1977) documented continuous interchange between the three main realms—Paleotethys, North American, and Boreal (Fig. 2)—but not exclusive provincialism. Ross (Reference Ross and Scholle1995) introduced a fourth realm, called Panthalassa or Sonomia, including some terranes in parts of Japan, the southern Russian Far East, British Columbia, and New Zealand. In the Mississippian, geographic and stratigraphic distribution of foraminifers are better known than those of calcareous algae.

Previous data on Fusulinata foraminifers from the Maritimes Basin are restricted to a limited number of publications (Mamet, Reference Mamet1968, Reference Mamet1970; Brisebois and Mamet, Reference Brisebois and Mamet1974; Jansa et al., Reference Jansa, Mamet and Roux1978; Brisebois, Reference Brisebois1979; Jansa and Mamet, Reference Jansa and Mamet1984). It is noteworthy that taxa recorded by Brisebois (Reference Brisebois1979) are rather similar to those of Jansa et al. (Reference Jansa, Mamet and Roux1978) and Mamet (Reference Mamet1970), and they do not contribute to new occurrences of taxa. In total, ~50 taxa have been listed by the previous authors. Mamet (Reference Mamet1970) based his attribution of the fauna to the North American Realm on the occurrence of Zellerinella Mamet, Reference Mamet1981, and mostly by the absence of some typical Paleotethyan taxa, e.g., Loeblichia Cummings, 1955 (Cummings, Reference Cummings1955a), Valvulinella Schubert, Reference Schubert1908, Omphalotis omphalota (Rauzer-Chernousova and Reitlinger in Rauzer-Chernousova et al., Reference Rauzer-Chernousova, Belyaev and Reitlinger1936), and Archaediscus karreri Brady, Reference Brady1873. Jansa and Mamet (Reference Jansa and Mamet1984) further extended the comparison, including more detailed paleobiogeographic maps of the geographic distribution of Howchinia Cushman, Reference Cushman1927, Bradyina Möller, Reference Möller1878, Lituotubella Rauzer-Chernousova, 1948 (Rauzer-Chernousova, Reference Rauzer-Chernousova1948b), and Omphalotis Shlykova, Reference Shlykova1969 (all absent in the Maritimes Basin), and consideration that the distance between Newfoundland and Ireland was at least 1,000 km separated by a deep ocean, which did not permit faunal interchange, and rejecting contemporaneous paleogeographic reconstructions locating the Maritimes Basin close to Spain or the Moroccan Meseta.

Although most foraminifers recorded in the Visean-early Serpukhovian Windsor Group are cosmopolitan, their relative abundance is distinct in the different paleobiogeographic domains (Mamet, Reference Mamet1970, fig. 15), but could also be subject to paleoecological constraints (e.g., Mamet and Skipp, Reference Mamet and Skipp1979). The basal Windsor Group strata comprises a thick interval of evaporites resting on a single marine carbonate unit (Macumber Formation), which defines the base of the group (Fig. 3) and provides the single potential source of foraminiferal data that have proven rare at this stratigraphic level. Thick lower Windsor Group evaporites imply a lack of open marine connections, which would necessarily be reflected in the benthic fauna and result in a limited foraminiferal population. These ‘reduced’ suites are not themselves similar, but they are similarly reduced, as in other apparently better-connected marine basins, e.g., in SW Spain (Cózar, Reference Cózar2003) where the foraminiferal assemblages show many dissimilarities (in diversity, abundance, and first occurrences of taxa) compared with neighboring basins in Morocco, France, and England. In a similar manner, the Maritimes Basin it notable for the rarity of one of the most diagnostic North American taxa, Eoendothyranopsis Reitlinger and Rostovzeva in Reitlinger, Reference Reitlinger1966, which is widespread in Visean North American successions (e.g., Mamet and Skipp, Reference Mamet and Skipp1970a, Reference Mamet and Skippb), but it is also common in Boreal and northwestern Paleotethyan realms (e.g., Loeblich and Tappan, Reference Loeblich and Tappan1987).

Another constraint is that the most diverse and richer realms (both in terms of numbers of genera and species, and also number of specimens) are the Paleotethyan and Boreal realms (Mamet and Skipp, Reference Mamet and Skipp1970a, Reference Cózar, García-Frank, Somerville, Vachard, Rodríguez, Medina-Varea and Said1979; Mamet, Reference Mamet, Kauffman and Hazel1977; Davydov, Reference Davydov2014) as well as realms with more endemic taxa. Thus in the Maritimes Basin, the absence of more numerous Paleotethyan taxa is more likely for North American affinities. A final constraint is the established migration routes for foraminifers. According to Mamet and Skipp (Reference Mamet and Skipp1970a) and Mamet (Reference Mamet, Kauffman and Hazel1977), most foraminifers are Euroasiatic in origin and migrated westward to western Europe and later to American and Arctic realms. This migration route was established on the basis of: (1) the earliest Late Devonian Endothyridae flourished in Eurasia but are rarely observed in North America; (2) the presence of complete phylogenetic lines in Europe but incomplete ones in North America; (3) impoverished microfauna in North America in regard to Eurasian assemblages, and with few endemic taxa; and (4) heterochronism of the base of the acmes and first occurrences (the oldest forms always occur first in Eurasia, then in the Arctic, and finally in the North American Cordillera). This direction in essence suggests that a communication route had to have existed between western Europe and eastern North America, and those taxa recorded in basins such as the Midcontinent had to have crossed using the Rheic Ocean and then via regions with more similarities with western Europe, i.e., the Maritimes Basin. However, some taxa must have migrated via the northern Boreal Ocean through the Franklinian corridor and Alaska (Harris et al., Reference Harris, Brenckle, Baesemann, Krumhardt and Gruzlovic1997; Davydov and Cózar, Reference Davydov and Cózar2019; Fig. 2).

A distinctive feature of the Maritimes Basins, as noted by Mamet (Reference Mamet1970) and Jansa and Mamet (Reference Jansa and Mamet1984), is the absence of typical large foraminifers recorded in the Paleotethys realm (e.g., Omphalotis omphalota, large Archaediscus Brady, Reference Brady1873, Bradyina, Janischewskina Mikhailov, Reference Mikhailov1939). The absence of these taxa in the Maritimes Basin is significant, but even in better-connected marine basins in SW Europe, they can show a similar phenomenon. For instance, in Sierra Morena in SW Spain, which should be paleogeographically relatively close to the Maritimes Basin, a typical late Visean-early Serpukhovian succession occurs (Cózar, Reference Cózar2003). Currently, from this succession, more than 4,000 thin sections have been studied, and only one specimen of Bradyina has been recorded, and no more than five specimens of Janischewskina. In addition, only sparse specimens of the large species of Archaediscus have been recorded, and the largest species are absent, compared to successions in Britain and Ireland. Thus, the absence of certain taxa, although at first glance might seem to provide a solid paleogeographic argument, could on the other hand be explained by responses to paleoecological constraints. Hence, the absence of some species is not exclusive to the Maritimes Basin, and needs to be further investigated due to similar patterns in unquestionable Paleotethyan basins. Furthermore, Jansa and Mamet (Reference Jansa and Mamet1984) considered the poor assemblages of the Maritimes Basin as being themselves characteristic and caused by a certain isolation from the main region of marine sedimentation and migration routes.

The second main argument in the comparison of Maritimes Basin foraminifers with those of the North American Realm, is the genus Zellerinella (= Zellerina Mamet in Mamet and Skipp, Reference Mamet and Skipp1970b, preoccupied), which was formerly considered endemic to this realm (Mamet, Reference Mamet1974c; Armstrong and Mamet, Reference Armstrong and Mamet1977). Equatorial sections might be confused with Eostaffella Rauzer-Chernousova, 1948 (Rauzer-Chernousova, Reference Rauzer-Chernousova1948a), Endostaffella Rozovskaya, Reference Rozovskaya1961, or other similar planispiral genera, but the axial sections are more distinctive. Since these earlier studies, the taxonomy of this taxon has progressed notably, and species originally interpreted as a primitive Millerella Thompson, Reference Thompson1942 by Zeller (Reference Zeller1953) (e.g., Millerella tortula Zeller, Reference Zeller1953 and Millerella designata Zeller, Reference Zeller1953) were included in the genus Zellerina/Zellerinella by Mamet in Mamet and Skipp (Reference Mamet and Skipp1970b) and Mamet (Reference Mamet1981), and was later reassigned to Paramillerella Thompson, Reference Thompson1951 (Brenckle and Groves, Reference Brenckle and Groves1981), Plectomillerella Brazhnikova and Vdovenko in Aizenverg et al., Reference Aizenverg, Astakhova, Berchenko, Brazhnikova, Vdovenko, Dunaeva, Zernetskaya, Poletaev and Sergeeva1983 (van Ginkel, Reference van Ginkel2010), or simply ‘Millerella’ (Gibshman, Reference Gibshman2001). The type species of the genus, Endothyra discoidea Girty, Reference Girty1915, is now considered an Endostaffella (Brenckle, Reference Brenckle2005). Independently of the preferred genus name, the same species have been recognized from China (e.g., Groves et al., Reference Groves, Wang, Qi, Richards, Ueno and Wang2012), eastern Europe (e.g., Gibshman, Reference Gibshman2003), western Europe (e.g., Cózar and Somerville, Reference Cózar and Somerville2016), and northern Africa (Cózar et al., Reference Cózar, Said, Somerville, Vachard, Medina-Varea, Rodríguez and Berkhli2011, Reference Cózar, Somerville, Vachard, Coronado, García-Frank, Medina-Varea, Said, del Moral and Rodríguez2016b). Thus, the genus is now considered as cosmopolitan and it cannot be used to ascribe the foraminiferal fauna of the Maritimes Basin to the North American Realm.

In the faunal list of Mamet (Reference Mamet1970), the occurrence of Plectogyranopsis ex gr. P. hirosei (Okimura, Reference Okimura1965) and Haplophragmella Rauzer-Chernousova and Reitlinger in Rauzer-Chernousova et al., Reference Rauzer-Chernousova, Belyaev and Reitlinger1936 need to be highlighted. The latter is a Paleotethyan taxon, and it is likely that specimens recorded in the Windsor Group might be included in the genus Mstinia Dain in Dain and Grozdilova, Reference Dain and Grozdilova1953. Only Mstinia irregularis (Rauser-Chernousova, Reference Rauzer-Chernousova1938) has been documented in the North American craton by Rich (Reference Rich1980). True Haplophragmella seems to be restricted to the former Soviet Union basins, and most specimens (if not all) recorded in western Europe need to be referred to Mstinia/Nevillea Conil and Lys in Conil et al., Reference Conil, Longerstaey and Ramsbottom1980 (Pille, Reference Pille2008; Vachard et al., Reference Vachard, Pille and Gaillot2010). Plectogyranopsis hirosei is only known from the Paleotethys Realm (eastern and western), except in the Arctic (Mamet et al., Reference Mamet, Pinard and Armstrong1993). Endothyranella sp. is reinterpreted here as Mikhailovella gracilis (Rauser-Chernousova, 1948 [Rauzer-Chernousova, Reference Rauzer-Chernousova1948a]), a typical Paleotethyan taxon, and Mikhailovella sp. of Mamet (Reference Mamet1970) is rather similar to the Mikhailovella fresnedosensis Cózar, Reference Cózar2001 recorded at Sierra Morena (Cózar, Reference Cózar2001). In addition, the Maritimes Basin assemblages also contain Omphalotis, Pseudoendothyra Mikhailov, Reference Mikhailov1939, and Pseudolituotuba Vdovenko, Reference Vdovenko1971, genera typically represented in the Paleotethyan and Boreal realms.

Koktjubina Marfenkova, Reference Marfenkova1991 was originally described from Kazakhstan by Marfenkova (Reference Marfenkova1991), and she also included a previously described species from Kazakhstan by Vdovenko (Reference Vdovenko1962), Spiroplectammina exotica Vdovenko, Reference Vdovenko1962, and a species described from the Windsor Group by Mamet (Reference Mamet1970), Biseriammina? windsorensis Mamet, Reference Mamet1970. The genus is predominantly of Paleotethyan affinities, although some rare exceptions are known from the Midcontinent. Rich (Reference Rich1980, pl. 5, fig. 1, non fig. 4) determined Biseriella? exotica (Vdovenko, Reference Vdovenko1962) in the southern Appalachians, and the specimens identified as Biseriella parva (Chernysheva, Reference Chernysheva1948) (pl. 5, figs. 2, 3, 6, 7, 10) are also attributable to Koktjubina. Later, Rich (Reference Rich1986, pl. 1, figs. 14–15) identified similar specimens of Biseriella parva as Biseriella exotica. This species, now Koktjubina exotica (Vdovenko, Reference Vdovenko1962), might be also present in the Peratrovich Formation of southern Alaska (Mamet et al., Reference Mamet, Pinard and Armstrong1993, pl. 13, fig. 7 only).

Three species of Koktjubina are recorded in Ireland, i.e., Koktjubina? atlantica Cózar and Somerville, Reference Cózar and Somerville2012, Koktjubina windsorensis (Mamet, Reference Mamet1970), and Koktjubina exotica. The most evolved species, described as Kokjubina? atlantica by Cózar and Somerville (Reference Cózar and Somerville2012), is widespread in Ireland and recorded in the Brigantian of SE Ireland. This species occurs in the Windsor Group (Mamet, Reference Mamet1970, pl. 1, fig. 5, as undetermined Biseriamminidae) and in the Canadian Cordillera (Mamet, Reference Mamet1976, pl. 81, figs. 12, 13, as Biseriella sp.). Koktjubina windsorensis is recorded only in the Benburb area of Northern Ireland (see location, Mitchell and Mitchell, Reference Mitchell and Mitchell1983), where it occurs in the latest Asbian and Brigantian (Cózar and Somerville, Reference Cózar and Somerville2012). As mentioned above, Koktjubina windsorensis is known throughout the Windsor Group in the Maritimes Basin, where it was identified as a species of Biseriammina Chernysheva, Reference Chernysheva1941 by Mamet (Reference Mamet1970). Its first appearance in the Maritimes Basin in lower Windsor Group strata differs from its most commonly reported occurrences in the late Visean and Serpukhovian (e.g., von Bitter et al., Reference von Bitter, Giles and Utting2007). The third species recorded in Ireland is Koktjubina exotica, which occurs in the Benburb area and in NW Ireland, but as mentioned above, also in the Midcontinent. These three species clearly suggest a faunal interchange between the Maritimes Basin and Ireland, and Koktjubina windsorensis seems to be endemic to the Maritimes Basin and Northern Ireland.

Jansa et al. (Reference Jansa, Mamet and Roux1978) and Brisebois (Reference Brisebois1979) documented, in widely separated portions of the Maritimes Basin, the occurrence of Polysphaerinella bulla Mamet, Reference Mamet1973. Described from Belgium and France (Conil and Lys, Reference Conil and Lys1964; Mamet, Reference Mamet1973), this taxon is a unilocular tuberitinid with secondary spheres (see Vachard, Reference Vachard and Montenari2016). It is otherwise known only from basins in the western Paleotethys, including Ireland and Britain (e.g., Vachard and Tahiri, Reference Vachard and Tahiri1991; Cózar and Rodríguez, Reference Cózar and Rodríguez2000; Pille, Reference Pille2008).

On the other hand, revision of foraminiferal assemblages previously published by other authors in von Bitter et al. (Reference von Bitter, Giles and Utting2007) are typically Paleotethyan in origin. Moreover, it can be concluded from the above-discussed data, that the foraminiferal genera from the Maritimes Basin are typically European and north African (see Table 2). Thus, in summary: (1) there is a single foraminiferal taxon (Eoendothyranopsis) in the Maritimes Basin assemblages that is considered more common in the North American Realm, although it has not been illustrated; (2) there are three typical Paleotethyan foraminiferal species: Plectogyranopsis hirosei, Mikhailovella gracilis, and the unilocular Polysphaerinella bulla, as well as the genera Haplophragmina Reitlinger, Reference Reitlinger1950, Omphalotis, Pseudoendothyra, and Pseudolituotuba; (3) there is one virtually endemic Paleotethyan genus, Koktjubina, of which one species (Koktjubina windsorensis) is known only from the Maritimes Basin and Northern Ireland; and (4) one other species (Mikhailovella fresnedosensis) is only recorded in the Maritimes Basin and SW Spain.

Another interesting feature of the foraminiferal assemblages of the Maritimes Basin is that they occur at similar stratigraphic levels as in western Europe (von Bitter et al., Reference von Bitter, Giles and Utting2007). It is well-known that the majority of North American taxa originated in the Paleotethys realm, and that they migrated westward. This process of migration is characterized by a delay of 2−3 Myr, and even up to 5 Myr, before their first appearances in North America, compared to the Paleotethys realm (Mamet, Reference Mamet, Kauffman and Hazel1977; Davydov, Reference Davydov2014). The apparent absence of these lags in the Maritimes Basin also suggests Paleotethyan affinities for the fauna of the Maritimes Basin.

Other fossil groups

Conodonts

The main studies of conodont faunas from the Maritimes Basin are those of Globensky (Reference Globensky1967), von Bitter (Reference von Bitter1976), and von Bitter and Plint-Geberls (Reference von Bitter and Plint-Geberls1982, Reference von Bitter and Plint-Geberls1987), subsequently summarized by von Bitter et al. (Reference von Bitter, Giles and Utting2007). Only Globensky (Reference Globensky1967) suggested that the conodont assemblages were representative of the North American realm, although following the reinterpretation of some of Globensky's specimens by von Bitter (Reference von Bitter1976), the assemblage has more recently been considered as Eurasian. This has been corroborated in the biogeographic provinces defined by Higgins (Reference Higgins, Neale and Brasier1981), and more recently, it has been recognized that common taxa are shared between the Maritimes Basin and Britain, e.g., Mestognathus Bischoff, Reference Bichoff1957, Taphrognathus transatlanticus von Bitter and Austin, Reference von Bitter and Austin1984, Clydagnathus windsorensis (Globensky, Reference Globensky1967), Vogelgnathus pesaquidi (Purnell and von Bitter, Reference Purnell and von Bitter1992), Vogelgnathus campbelli (Rexroad, Reference Rexroad1957), and Vogelgnathus postcampbelli (Austin and Husri, Reference Austin and Husri1974) (von Bitter and Austin, Reference von Bitter and Austin1984; von Bitter et al., Reference von Bitter, Sandberg and Orchard1986; Purnell and von Bitter, Reference Purnell and von Bitter1992).

Rugose corals

Since the pioneering work of Lewis (Reference Lewis1935), rugose corals from the Maritimes Basin have been traditionally considered paleobiogeographically closer to western European assemblages than to American rugose-coral assemblages (Hill, Reference Hill and Hallam1973, Reference Hill1981). Although taxonomic determinations were not conclusively documented, Poty (Reference Poty, Hicks, Henderson and Bamber2002) recently revised those rugose corals and confirmed that most are typically represented in western Europe, notably in basins from northern England, Ireland, and southern France (Actinocyathus d’Orbigny, Reference Orbigny1849, Amplexizaphrentis Vaughan, Reference Vaughan1906, Axophyllum Milne-Edwards and Haime, Reference Milne-Edwards and Haime1850, Koninckophyllum Thomson and Nicholson, Reference Thomson and Nicholson1876, Lonsdaleia McCoy, Reference McCoy1849, Nemistium Smith, Reference Smith1928, Palastraea McCoy, Reference McCoy1851, and Siphonodendron McCoy, Reference McCoy1849).

Miospores

Following the study by Clayton (Reference Clayton1985), palynologists have widely accepted that Atlantic Canada belongs to the same paleobiogeographic province as Europe. Biostratigraphic zones defined in the Windsor Group and coeval strata (e.g., Utting, Reference Utting1987; Utting and Giles, Reference Utting and Giles2004) are comparable to those used in western Europe (e.g., Neves et al., Reference Neves, Gueinn, Clayton, Ioannides and Neville1972, Reference Neves, Gueinn, Clayton, Ioannides, Neville and Kruszewska1973; Clayton et al., Reference Clayton, Coquel, Doubinger, Gueinn, Loboziak, Owens and Streel1977). A close comparison of both spore zonal schemes was documented by Utting and Giles (Reference Utting and Giles2004), and the European miospore zonal scheme, as well as European regional substages, are now used in biostratigraphic analyses of the region (e.g., Jutras et al., Reference Jutras, Prichonnet and Utting2001, Reference Jutras, McLeod and Utting2015; von Bitter et al., Reference von Bitter, Giles and Utting2007; Utting and Giles, Reference Utting and Giles2008).

Brachiopods

Von Bitter and Legrand-Blain (Reference von Bitter and Legrand-Blain2007) studied the gigantoproductids from the Windsor Group in Nova Scotia, based on specimens they collected themselves and those illustrated by previous authors. They recognized several taxa denominated as typical ‘Old World’ brachiopods, especially highlighting the occurrence of Latiproductus sp. and Gigantoproductus cf. G. crassiventer (Prentice, Reference Prentice1949), and the close relationship between Nova Scotia and central England.

Trilobites

Trilobites have not yet been studied in detail in the region, but Brezinski (Reference Brezinski2003) recorded Paladin eichwaldi (Fischer von Waldheim, Reference Fischer von Walddheim and Eichwalds1825) in the Windsor Group, which he interpreted to be a typical European taxon.

Paleobiogeographic results

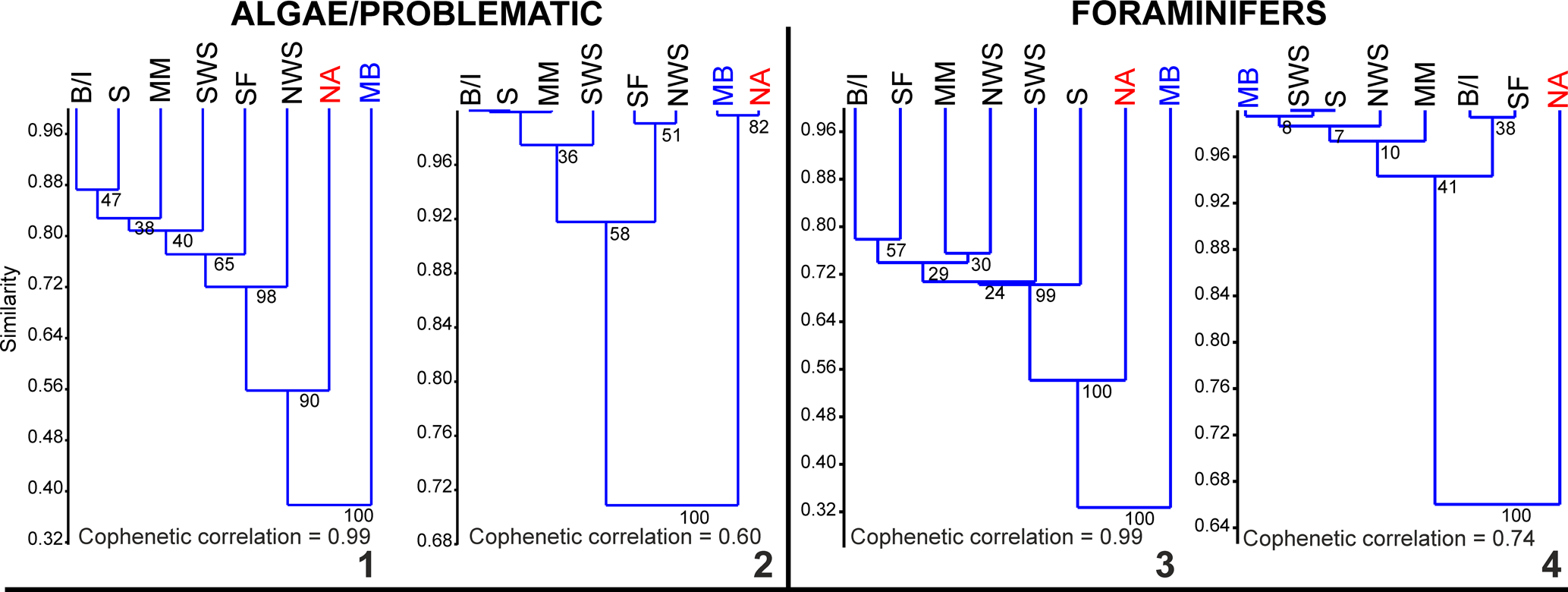

The dendrograms resulting from hierarchical cluster analyses of algae/problematic algae and foraminifers using the Jaccard coefficient show a low similarity index for the Maritimes Basin (Fig. 4.1, 4.3). The highest similarity indices obtained with algae (0.44) and foraminifers (0.34), although still low values, suggest a closer position for the Maritimes Basin with the North American craton. However, in the case of foraminifers, the similarity index with SW Spain is also 0.34. This is interpreted as the result of ‘missing’ or under-represented data in the Maritimes Basin, which gives an artificial coincidence with the poorest North American Realm, or is composed of numerous endemic forms. The dendrograms using the Raup-Crick coefficient provide more diverse results. The algal cluster also shows a close position of the Maritimes Basin with North America (Fig. 4.2). In contrast, the foraminiferal cluster shows higher similarities with terranes in Spain and Gondwana (Fig. 4.4). It might be possible to explain the apparent ‘anomaly’ of the algal data in both the Jaccard and Raup-Crick coefficient methods, in which they show closer affinity to North America, as a result of the fewer number of genera (one-third less) in the database compared to the foraminifers.

Figure 4. Dendrograms from hierarchical cluster analyses of algae/problematic algae and foraminifers using the Jaccard coefficient (1, 3), and Raup-Crick coefficient (2, 4) by unweighted pair-group average (UPGMA) method (node percentages are bootstrap support with 1,000 iterations). B/I = Britain and Ireland; MB = Maritimes Basin; MM = Moroccan Meseta; NA = North America; NWS = NW Spain; S = Sahara; SF = southern France; SWS = SW Spain.

The ordination methods (NMDS) using the Jaccard coefficient always suggest widely distant positions between the Maritimes Basin and North American and Paleotethyan realms, slightly closer to the Paleotethys realm, specifically, the Gondwana craton (Sahara) (Fig. 5.1). The foraminifers show closer affinities with the northern Variscan Front (Moroccan Meseta and Sierra Morena, SW Spain) (Fig. 5.3).

Figure 5. Non-metric Multidimensional Scaling (NMDS) ordination method using the Jaccard coefficient (1, 3) and Raup-Crick coefficient (2, 4) of algae/problematic algae and foraminifers. Abbreviations as in Fig. 4.

These affinities are emphasized using the Raup-Crick coefficient, in which the Maritimes Basin is mostly in an intermediate position between North America and western Europe/northern Africa, which is the most logical presumption. The closer distances, depending on the fossil group, are with the southeastern terranes (NW Spain) and Gondwana (Sahara) (Fig. 5.2, 5.4), but not with Britain/Ireland, as previously authors have proposed.

To minimize this plausible ‘absence of data’ effect in the Maritimes Basin, both groups were analyzed together, and the biota results show a closer proximity to Gondwana or the southern terranes (Fig. 6), at similar distances than with North America. Secondarily, it is observed that there is a close relationship between the Maritimes Basin and terranes in the northern Variscan Front, e.g., SW Spain. However, a close relationship with Laurussia was not observed, as some particular taxa of foraminifers, conodonts, brachiopods, and miospores have suggested. It must be noted that the analysis for algae has been run also considering only Kulikia and not Pekiskopora, and the results were similar. This confirms that the occurrence of a particular taxon did not exert excessive weight in paleobiogeographic comparisons.

A major concern about the lack of diversity of the Maritimes Basin is seen in the dichotomic results using the Jaccard or Raup-Crick coefficients for individual fossil groups (Figs. 4, 5). The Jaccard coefficient is one of the more widely used coefficients for biogeographic models, but owing to missing data, the Raup-Crick coefficient has become more commonly used in paleobiogeographical models, to highlight unusual taxa and not the more widely expanded taxa. This difference between the indices is minimized when the database is larger (Fig. 6), showing similar results.

The lack of diversity is a marked handicap in analysis of the fauna and flora of the Maritimes Basin, because the total number of recorded foraminiferal and algal genera are only one-quarter or one-third as large as those in the Paleotethys Realm (26 vs 107 and 23 vs 70, respectively), and one-half of those in North America (26 vs 53, and 23 vs 42, respectively) (already considered as containing impoverished assemblages; see Tables 1, 2) Thus, although low diversity was considered a characteristic feature of the Maritimes Basin by Jansa and Mamet (Reference Jansa and Mamet1984), it is apparent that further research is necessary to increase its recorded diversity, which currently looks insufficient; owing to this apparent low diversity, the statistical results have to be taken with some caution.

Paleobiogeographic implications

Because the oldest Visean rocks of the Windsor Group succession are dominated by thick evaporites (Fig. 3), Mamet (Reference Mamet1970) and Jansa and Mamet (Reference Jansa and Mamet1984) postulated that the Maritimes Basin was a semiclosed platform. This was invoked for the precipitation of evaporites, because most paleogeographic reconstructions show Ireland/Britain and the Maritimes Basin at approximately the same low latitude, between 10° and 20°S (e.g., Roy, Reference Roy1973; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Briden and Drewry1973; but not Ziegler, Reference Ziegler1978). Jansa and Mamet (Reference Jansa and Mamet1984) considered that the distance between Ireland and the Maritimes Basin was at least 1,000 km, and separated partly by a graben/rift structure (Rockall-Hatton Bank of Le Pichon, Reference Le Pichon1977 and Ziegler, Reference Ziegler1978) and involved a wide Rheic Ocean. Recent reconstructions suggest that this distance was ~800 km during the Devonian (Waldron et al., Reference Waldron, Schofield and Murphy2018). Thus, it can be assumed that the distance during the Mississippian was even less, due to the closing related to the progressing Variscan orogeny.

Despite the faunal, floral, and stratigraphical similarities between the Maritimes Basin and western European/northern African basins, it is certainly apparent that there are also dissimilarities, which prevent a perfect interconnectedness. On the other hand, the tectonic style in the Maritimes Basin is more typically Appalachian, following the assumed attachment of the terranes of the North American region since the Devonian.

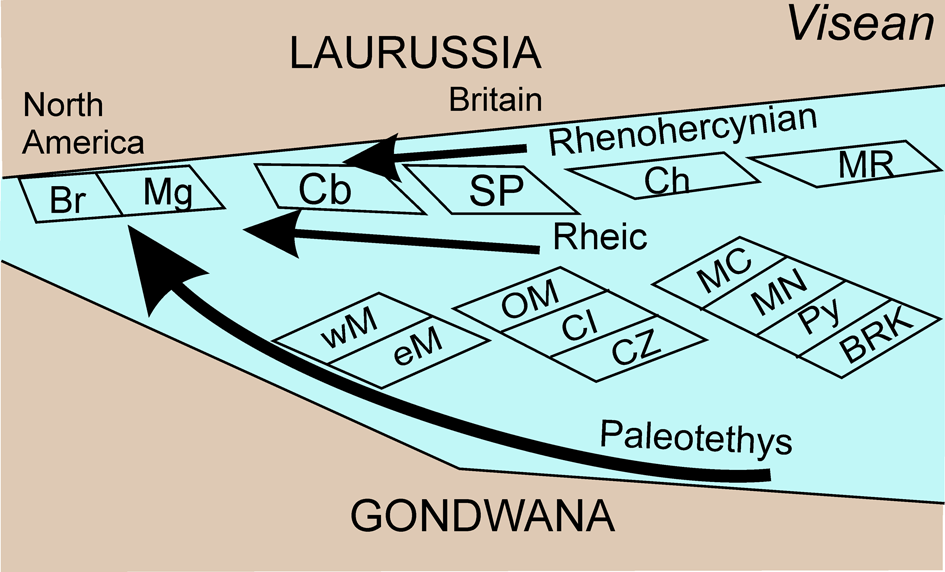

The presence of a land barrier between western Europe and Newfoundland was discussed and dismissed by previous authors (e.g., Jansa and Mamet, Reference Jansa and Mamet1984). We agree with that conclusion, because the existence of a land barrier would have prevented the marine faunal and floral interchange that is now well known. The occurrence of an ocean that acted as a potential paleobiological barrier, controlled by currents, water depth, and ocean width (Jansa and Mamet, Reference Jansa and Mamet1984), is the most likely hypothesis. However, the presence of this ocean disagrees with the hypothesis that considered that the closure of the Rheic Ocean occurred during the Devonian or in the earliest Mississippian (e.g., Nance et al., Reference Nance, Gutiérrez-Alonso, Keppie, Linnemann, Murphy, Quesada, Strachan and Woodcock2012) and only a Rhenohercynian Ocean could have been open from the Middle to Late Mississippian (see Fig. 7). The close similarities and clear influence of Paleotethyan late Visean assemblages suggest a narrower ocean than previously supposed, and also, not very deep, to allow migration of most benthic biota. It is difficult to estimate ocean width, but it was likely to have been <1,000 km, as recent reconstructions have suggested. Whatever the separation, fluid and constant faunal/floral interchange must have been permitted. However, the low diversity of the Maritimes Basin assemblages is a conditioning factor because it might be the result of the few studies in the region, or it might be actual low diversity. In the first case, if the diversity of assemblages (number of genera) could be increased as a result of more studies in the region, that would imply a more constant interchange of fauna, and thus, a narrower oceanic width. In contrast, if, after more studies in the region, the diversity is not significantly increased, this would imply a certain isolation of the Maritimes Basin, either by a wider ocean or by stronger oceanic currents, allowing only sporadic interchange of fauna/flora with the Paleotethys realm (as during major transgressive events). It is also noteworthy that during sedimentation of the basal Windsor Group (evaporites of cycle 1, but also in cycles 2−5; Fig. 3), the conditions were distinctly different from those in most of western Europe, i.e., in a restricted basin, with poor communication with the ocean that did not allow a fluid faunal interchange. However, episodes of evaporite precipitation are known in the Mississippian of Ireland, England, Scotland, and Belgium (West et al., Reference West, Brandon and Smith1968; Delmer, Reference Delmer1988; Millward et al., Reference Millward, Davies, Williamson, Curtis, Kearsey, Bennett, Marshall and Browne2018). Nevertheless, the evaporite-rich character of the Windsor Group, likely in part, explains the strongest faunal differences in the lower part of the succession, irrespective of whether it is early Visean or middle Visean.

Figure 7. Paleobiogeographical sketch of the Maritimes Basin and basins in western Europe and North Africa during the late Visean-early Serpukhovian. Black arrows are plausible migration routes to the Maritimes Basin. Terranes based on Stampfli et al. (Reference Stampfli, Hochard, Verard, Wilhem and von Raumer2013). Br = New Brunswick; BRK = Betics-Rif-Kabbilies; Cb = Coastal Block; Ch = Channel; CI = Central Iberian Zone; CZ = Cantabrian and Asturian-Leonese Zone; eM = eastern Moroccan Meseta; MC = Central Massif of France; Mg = Meguma; MN = Montagne Noire; MR = Mid-Germany rise; OM = Ossa-Morena Zone; Py = Pyrenees and Catalonia; SP = South Portuguese Zone; wM = western Moroccan Meseta.

The resulting data are more controversial, perhaps, in part, arising from the paucity of the eastern Canadian assemblages. The most widely supported hypothesis is that direct communication between the Maritimes Basin and Ireland/Britain is not obviously supported by statistical analyses, but rather suggests a stronger similarity and closer geographic proximity with Gondwana and the terranes in the Variscan Front. This implies that although individual species might imply an artificially closer paleobiogeographic relationship between the Maritimes Basin and Ireland/ Britain, the whole assemblage is more representative of Gondwana. Certainly, lateral migration through the Rheic Ocean platforms is more easily envisaged, and the migration of Albertaporella from the North American Realm to the south of Ireland during the early Visean confirms a still-open Rheic Ocean. During the late Visean-early Serpukhovian, the migration of many similar species of foraminifers, conodonts, rugose corals, and gigantoproductid brachiopods to the Appalachians confirms that that communication still existed.

In some paleogeographic models (e.g., Stampfli et al., Reference Stampfli, Hochard, Verard, Wilhem and von Raumer2013), this communication between the Maritimes Basin and Britain could be also possible via the Rhenohercynian Ocean, which was open during the Mississippian (Fig. 7). A rather similar position of the terranes and continents can be observed in the reconstructions by Blakey (Reference Blakey2008, fig. 10C), with the Sahara and the Reguibat promontory in front of the Maritimes Basin, although in this reconstruction the Rhenohercynian Ocean was not connected. Tectonic and sedimentological models promote comparison of the Maritimes Basin with those in Ireland and Britain (e.g., Waldron et al., Reference Waldron, Schofield and Murphy2018), and it is automatically assumed that the biological influence of those northern regions is inherited. However, alternative scenarios might need to be considered in which the benthic biota arrived in the Maritimes Basin by crossing the Paleotethys Ocean from more southerly positions near the Gondwana coast, or from the northwestern terranes across a still-open Rheic Ocean (Fig. 7). This would suggest narrower oceans in this region for the late Visean-early Serpukhovian period. Indirectly, for this communication with the Paleotethys Ocean to occur, it is envisaged that the Moroccan Meseta was not attached to Gondwana during the Visean (Fig. 6), a fact described only for the early to mid-Visean (Cózar et al., Reference Cózar, Vachard, Izart, Said, Somerville, Rodríguez, Coronado, El Houicha and Ouarhache2020), whereas for the late Visean-early Serpukhovian interval, it is not yet clearly defined. However, if the Meseta was attached to Gondwana, this would imply higher similarity indices between the Meseta and the Maritimes Basin than with Gondwana, which is not the case. The occurrence of Saharan assemblages in the Maritimes Basin suggests that the annexation of the Moroccan Meseta to Gondwana had not happened during the late Visean and early Serpukhovian.

Paleobiogeographic models are, in general, in disagreement with the paleogeographic models based on tectonics, magmatism, or paleomagnetism. For the last, there is a predominance of models that suggest that the closure of the Rheic Ocean occurred during the Devonian, with no connection between the Rheic and Paleotethys oceans (e.g., Kroner and von Romer, Reference Kroner and von Romer2013; Stampfli et al., Reference Stampfli, Hochard, Verard, Wilhem and von Raumer2013; Scotese, Reference Scotese2015), whereas another group of authors considered that the gateway between the two oceans existed until the Permian (Vai, Reference Vai2003; Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, Aleinikoff and Wintsch2007; Domeier et al., Reference Domeier, Torsvik and van der Voo2012). Rarely, some authors have highlighted the importance of fossil groups for these paleogeographic reconstructions for the Carboniferous (e.g., Cocks and Torsvik, Reference Cocks and Torsvik2011). Related to this aspect, ammonoids, rugose corals, brachiopods, and foraminifers do not show synchronicity in the timing of the closure of the Rheic-Paleotethys gateway, ranging from the mid-Visean, late Visean, early Serpukhovian, and late Serpukhovian, respectively, but clearly, all are later than the Devonian (Korn et al., Reference Korn, Titus, Ebbighausen, Mapes and Sudar2012; Aretz et al., Reference Aretz, Dera, Lefebvre, Donnadieu, Godderis, Macouin and Nardin2013; Quiao and Shen, Reference Qiao and Shen2014, Reference Qiao and Shen2015; Davydov and Cózar, Reference Davydov and Cózar2019). The fauna and flora of the upper cycles of the Maritimes Basin (cycles 2−5), with strong similarities with the Paleotethys realm, confirm good communication at least until the early Serpukhovian (or a younger age for the Windsor-Codroy groups; von Bitter et al., Reference von Bitter, Giles and Utting2007). Anomalous impoverished Visean assemblages in the Maritimes Basin suggest at least intermittent communication with the North America Realm during the same period. Species in common between the Paleotethyan and the North American realms during the Visean/Serpukhovian confirm communication through the Maritimes Basin. Marine communication of the Paleotethys and North American realms through the Maritimes Basin ceased very near the beginning of the Serpukhovian with the termination of any open marine deposition that might have supported even impoverished marine faunas. This stratigraphic break is marked by the top of the Windsor and Codroy groups, assigned a latest Visean to earliest Serpukhovian age by von Bitter et al. (Reference von Bitter, Giles and Utting2007). In the Maritimes Basin, miospores recorded a major paleoenvironmental crisis in the Arnsbergian (late Serpukhovian) (Utting, Reference Utting1987; Utting and Giles, Reference Utting and Giles2008; Jutras et al., Reference Jutras, McLeod and Utting2015), a period associated with glacial episodes, shifts in carbon and oxygen isotopic data, and a global-scale late Paleozoic sea-level fall (Isbell et al., Reference Isbell, Miller, Wolfe and Lenaker2003; Grossman et al., Reference Grossman, Yancey, Jones, Bruckschen, Chuvashov, Mazzullo and Mii2008; Haq and Schutter, Reference Haq and Schutter2008; Mory et al., Reference Mory, Redfern, Martin, Fielding, Frank and Isbell2008; Gulbranson et al., Reference Gulbranson, Montañez, Schmitz, Limarino, Isbell, Marenssi and Crowley2010; Stephenson et al., Reference Stephenson, Angiolini, Cózar, Jadoul, Leng, Millward and Chenery2010; Barham et al., Reference Barham, Murray, Joachimski and Williams2012; Giles, Reference Giles2012; Davydov, Reference Davydov2014). These facts coincide with the ultimate closure of the Rheic-Paleotethys gateway, and thus, the formation of the so-called Alleghenian Isthmus, interpreted to have occurred during the late Serpukhovian (Davydov and Cózar, Reference Davydov and Cózar2019). Before the early Serpukhovian cessation of marine communication, and well before the onset of severe and extensive glaciations of the Pennsylvanian during the coldest times of the Paleozoic (Giles, Reference Giles2012), marine connections through the Maritimes Basin were at best intermittent and short-lived (Giles, Reference Giles2009) and limited to short episodes of glacioeustatic marine transgression. Until marine communication ceased, the biota of the Maritimes Basin reflects multiple sources with intermittent linkages to all of our studied regions.

Conclusions

Analyzing the foraminiferal taxa in the Maritimes Basin, several genera and species typically represented in the Paleotethys realm can be recognized, contrasting with previous studies that the Maritimes Basin lacked typical Paleotethyan genera and species. Typical North American fauna/flora are negligible or absent, and apparent similarities are based on the absence of typical Paleotethyan genera and species. Low diversity has been argued by some as a feature typical of the Maritimes Basin, although it could be simply a result of less-detailed paleontological works or the predominance of hostile facies.

The Maritimes Basin has been compared with basins in Laurussia, in particular Ireland and England. The influence of the Laurussian margin is supported by the occurrence of some species of brachiopods, miospores, and foraminifers, with dispersal via the Rhenohercynian Ocean. However, multivariate analysis of the marine benthic microfossils confirms that although the assemblages are of Paleotethyan affinities, they are closer to assemblages in the Gondwana platform and terranes of the Variscan Front (Moroccan Meseta/SW Spain). Owing to the relative position of the terranes between the Laurussia and Gondwana continents, we suggest that migration of the biota occurred not only via the incipient Paleotethys Ocean, but also by a still-open Rheic Ocean, with additional influence of the Rhenohercynian Ocean. Our assessment indicates multiple sources for the biota of the Maritimes Basin. Paleogeographic models that located the Maritimes Basin opposite the North African coast would fit better in the observed paleobiogeographic relationships.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank M. Aretz and an anonymous reviewer for their constructive comments. The research was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades (project CGL2016-78738BTE). We acknowledge support of the publication fee by the CSIC Open Access Publication Support Initiative through its Unit of Information Resources for Research (URICI).