Case Report

During a New York (USA) to Paris (France) flight, a few minutes after taking off, the stewards called for a physician because a man had fainted in business class; statistically, there is always a physician on board.Reference Albert 1 There were two physicians on board the flight: a psychiatrist and an orthopedic surgeon. They both proceeded to take care of the sick passenger. Upon their arrival, the patient was lying down on the floor but seemed to look well. He explained that when the stewards authorized to unfasten seatbelts, he pressed the command of his seat to extend the backrest, and then got sick and fainted. His medical history summed up in a pacemaker implantation in 1998. His pacemaker had been replaced two months earlier without any medical complications. The passenger wanted to repeat the scene by pressing the command of the seat and fainted again. The physicians tested the seat but nothing happened. The psychiatrist concluded that the passenger had flight anxiety. The passenger was then advised to choose another seat and rest. The flight ended without a hitch.

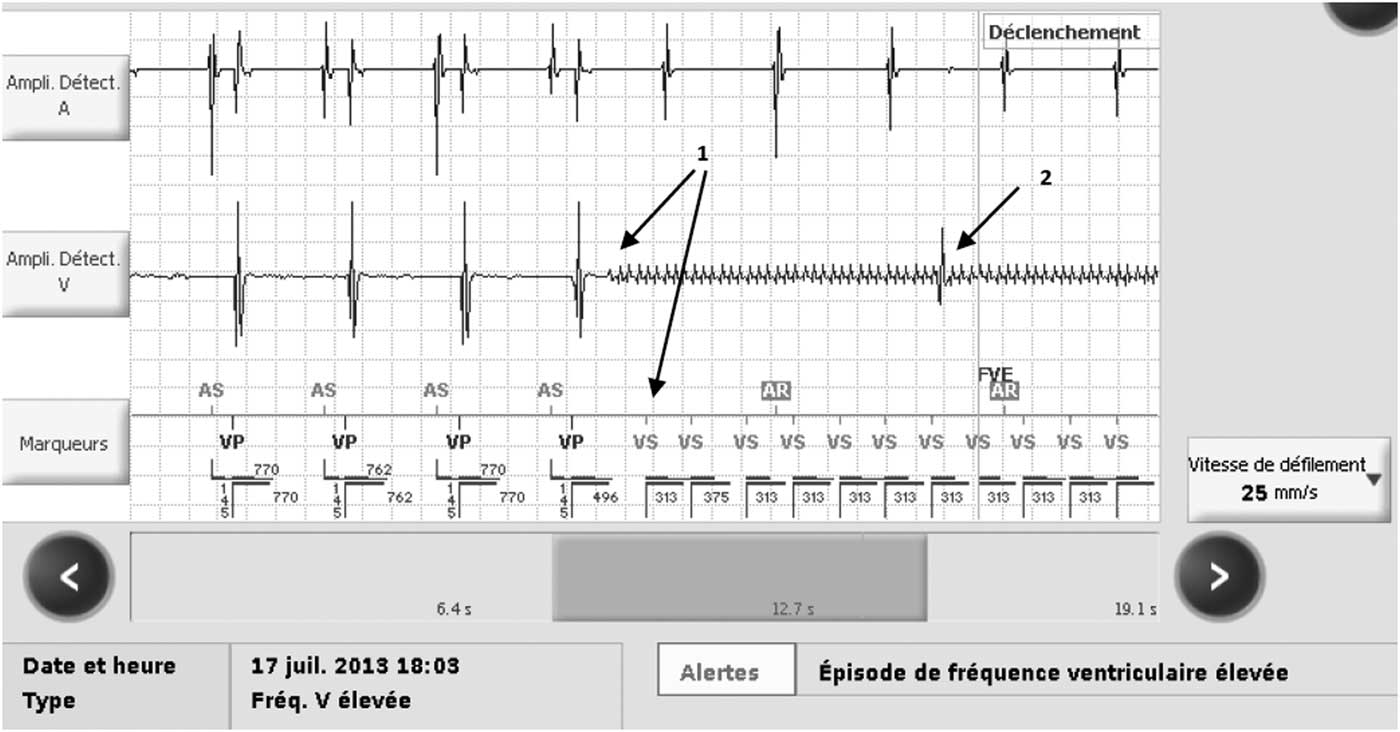

Once arrived in Paris, the passenger went to his cardiologist to check the pacemaker (Figure 1). The test showed that the pacemaker had been inhibited by a 50 Hz electric interference exactly during this flight.

Figure 1 Electrogram Recorded by the Pacemaker during the Flight. Note: The first and second lines refer to the activity sensed respectively in the atrium and in the ventricle. The third line shows the pacemaker interpretation of the above two lines. The beginning of this electrogram shows a spontaneous atrial rhythm (AS) and a ventricular-paced rhythm (VP) corresponding to a DDD mode. Suddenly appears an electrical interference noise on the ventricular lead (Arrows 1), which is sensed by the pacemaker as a succession of ventricular activities. Then, the pacemaker stops pacing. The second arrow (Arrow 2) shows the apparition of too slow an escape rhythm, which is not sufficient to prevent the faint. Abbreviations: AS, atrial sensed; AR, atrial sensed in refractory period; VS, ventricular sensed; VP, ventricular paced.

Discussion

Inappropriate cardiac pacemaker inhibition depends on lead-sensing abilities. Modern cardiac leads are bipolar; id est, they can sense the cardiac activity exclusively at the distal extremity of the lead which is in contact with the myocardium.Reference Kowalski, Ellenbogen, Wood and Friedman 2

In the 1990s, leads were still unipolar, and sensing was performed in a large electric field between the distal lead extremity and the cardiac generator. Cardiac-sensed signal had to be slightly screened in order to be confounded neither with pectoral or phrenic myopotentials, nor with 50 Hz electric current.Reference Astridge, Kaye, Whitworth, Kelly, Camm and Perrins 3 , Reference Jilek, Tzeis and Vrazic 4 Indeed, it could cause an inappropriate cardiac pacemaker inhibition.

As long as this interference persists, the pacemaker will be inappropriately inhibited, thereby preventing the delivery of cardiac stimulation. If the patient has no escape rhythm, this interference induces an asystole. Placing a magnet on a pacemaker will turn it into a DOO mode (deaf mode): the device restarts pacing the heart without analyzing the underlying rhythm. In this clinical case, the cardiologist lowered the ventricular detection ability to prevent recurrence of this issue. Regarding the interference, it should be considered that there was an electrical disorder in the seat.

Conclusion

While inappropriate pacemaker inhibition has become rarer with bipolar rather than with unipolar leads, it is still a recurrent issue. Any physician should have basic knowledge of pacemakers or defibrillators and should at least know when and how to use a magnet.