Presentations to general hospitals with self-harm are common and carry significant personal, social and health costs as well as increased morbidity and mortality. Current research shows several promising areas to focus on to improve outcomes after self-harm. First, there is regular written communication sent to patients after self-harm. In 2005 Carter et al developed an intervention tested with a Zelen randomised controlled trial (RCT) in which a series of eight ‘postcards’ were sent over 1 year after discharge to patients who had presented at emergency departments for self-poisoning. Reference Carter, Clover, Whyte, Dawson and D'Este1 At 1-year follow-up patients in the intervention group had half the number of readmissions than the control group (101 v. 192), although the proportion of people re-presenting in each group was not significantly different. Second, there is problem-solving therapy (PST), which is a brief focused psychological treatment that has been shown to be significantly more effective than control conditions with regard to improvements in depression, hopelessness and problem-solving ability in patients who have attended hospital after self-harm. Reference Townsend, Hawton, Altman, Arensman, Gunnell and Hazell2 A previous study by our group found that PST significantly reduced the proportion of people repeating after a year by about a third in those whose index episode was a repeat, but it had no effect in individual who were presenting for the first time. Reference Hatcher, Sharon, Parag and Collins3 With the current study we wanted to see if an enhanced package that included PST was also effective in people presenting for the first time. Third is assertive follow-up to ensure that management plans made in hospital are carried out once the person is discharged. There is some evidence that more assertive outreach after self-harm results in better attendance in out-patients although it is unclear whether this decreases the repetition rate. Reference Hawton, Townsend, Arensman, Gunnell, Hazell and House4 Fourth is improving risk management as current tools are unable to predict who will kill themselves or repeat self-harm. Fifth a neglected component of assessment in mental health, with a notable exception of ‘cultural services’, is the clinical assessment of identity and belonging in people who self-harm. This is particularly surprising given that having deficits in autobiographical memory Reference Pollock and Williams5 and a poor sense of belonging Reference Conner, Britton, Sworts and Joiner6 are common in people who self-harm. Last is the better care of people’s physical health as half the premature mortality after an episode of self-harm are as a result of non-suicide causes. Reference Hawton, Harriss and Zahl7

In the current study, we developed a package of care including components of each of these areas that was delivered to individuals after they had presented to a hospital emergency department with self-harm. By combining them together we aimed to replicate the package of interventions that a clinical ‘self-harm team’ could reasonably deliver and to test the idea that the package would be more effective than usual care. We hypothesised that the package of interventions would improve measures of distress, suicidal risk, quality of life and function after 3 months and 1 year.

Method

Trial design

The full study protocol for ACCESS has been published Reference Hatcher, Sharon, House, Collings, Parag and Collins8 (trial registration Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry ACTRN12609000641291). The trial was a Zelen RCT. In this design people who are identified as being eligible to participate in the study are randomised prior to giving consent. All people who participated in the study were required to give consent but the introduction to the study differed depending on whether they were randomised to the control or intervention group. People randomised to the control arm were invited to participate in the study by completing rating scales, questionnaires and interviews at baseline and follow-up. People randomised to the experimental arm were invited to participate in the study by completing rating scales, questionnaires and interviews at baseline and follow-up and were also invited to receive the intervention. Individuals who did not consent to take part in the study received the usual care following an episode of self-harm.

Participants

People were eligible for inclusion in the study if they had presented through the emergency department of one of the hospitals involved in the study following an episode of self-harm. People who required an interpreter were eligible for inclusion in the study. We defined self-harm as self-poisoning or self-injury, irrespective of motivation. Self-poisoning includes the intentional ingestion of more than the prescribed amount of any drug, whether or not there is evidence that the act was intended to result in death. This also includes poisoning with non-ingestible substances (for example pesticides), overdoses of recreational drugs and severe alcohol intoxication where the clinical staff considers such cases to be an act of self-harm. Self-injury is defined as any injury that has been self-inflicted.

Potential participants were excluded if they were aged under 17; were still at school; or were unable to give informed consent to be part of the study. Usually people who identified as Maori were recruited into Te Ira Tangata, the ‘sister-study’ to ACCESS. Te Ira Tangata was a Zelen RCT run at a similar time and in similar locations to ACCESS. It recruited Maori who presented to hospital with self-harm to be treated by Maori using a culturally appropriate intervention. However, during the first 3 months of the ACCESS trial and at Waikato district health board Te Ira Tangata was not recruiting. In these circumstances Maori who presented with self-harm were recruited into ACCESS. Ethical approval was received from the New Zealand Ministry of Health Central Regional Ethics Committee (CEN/09/04/011).

Study setting

The study was conducted in five hospitals in four district health boards in New Zealand: Waitemata (North Shore Hospital and Waitakere Hospital), Counties Manukau (Middlemore Hospital), Northland (Whangarei, Bay of Islands, Kaitaia and Dargaville Hospitals) and Waikato (Waikato Hospital). These district health boards were selected to provide a mix or rural, urban and cultural populations that would make any findings generaliseable to the wider New Zealand population.

Interventions

The experimental intervention package of care consisted of six elements.

Patient support for up to 2 weeks

This was one or two face-to-face or telephone sessions, depending on patient preference and feasibility, over the 2 weeks following the patient’s discharge from hospital. Research clinicians obtained the discharge plan developed by the assessing clinicians, checked that the patient understood it, assisted the patient to identify potential barriers to implementing the plan and helped the patient to follow through with the plan. The primary aim of patient support was be to ensure patients did not ‘fall through the cracks’. The research clinicians liaised with the mental health crisis and community mental health teams, alcohol and drug services and primary care services. Each patient support session included a risk assessment asking about thoughts and plans for self-harm. If a patient was identified as being at risk of self-harm a risk management protocol was followed.

Postcard contact for 1 year

Eight postcards were sent in sealed envelopes in months 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8,10 and 12 after the index episode. The cards contained a short message stating: ‘It has been a short time since you were in hospital and we hope things are going well for you. If you wish to drop us a note we would be happy to hear from you at the above address or the email below’. Postcards were signed by S.H.

Problem-solving therapy

This consisted of a planned four to six sessions in the 4weeks after the participant’s index presentation to hospital for self-harm. Patients were ineligible for PST if they were already in a dialectical behavioural therapy (DBT) programme; if brief PST would conflict with their management plan; if they lived or were moving out of area; if they were in prison or if there was a risk of harm to the research clinician. If they were ineligible for PST they were still eligible to receive other aspects of the treatment package and were included in the analysis. The PST model we used was conducted with individual patients and was based on the model originally defined by D’Zurilla & Goldfried. Reference D'Zurilla and Goldfried10 During PST sessions we aimed to teach the person to recognise and identify current problems and to develop a more structured approach to problem-solving. We created a clinician manual and a participant workbook to guide the structure of the PST therapy sessions. We defined completing PST as attending three or more sessions.

Improved access to primary care

We encouraged participants to attend their general practitioner (GP) for a physical health check, paying particular attention to cardiovascular risk factors, alcohol and smoking. In order to facilitate this, participants were offered a voucher that entitled them to one free visit with their GP.

A risk management strategy

The teams piloted a risk management strategy around the management of patients who were suicidal. This consisted of a checklist for patient support to ensure that key tasks were completed and questions asked. The research team met once a week to discuss adverse events defined as repeat episodes of self-harm, hospital re-presentation for any reason and suicides. A record was kept of these discussions, including any changes to process as a result of these discussions, and circulated to the team in the form of a ‘risk bulletin’.

Cultural assessment

We completed a cultural assessment on all participants paying particular attention to their sense of belonging and feelings around their ethnicity. Problems with sense of belonging were included in the problem-solving checklist for patients.

Treatment as usual

Treatment as usual (TAU) following self-harm varied and involved referrals to multidisciplinary teams for psychiatric or psychological assessment and intervention, referrals to crisis teams and/or recommendations for engagement with community alcohol and drug treatment centres. The discharge plan included referrals to more than one healthcare provider, or consisted solely of referral back to the patient’s GP.

Outcomes

The primary outcome measure was re-presentation to any hospital in New Zealand for self-harm within 1 year of the index presentation. This was assessed by interrogating district health board electronic systems and Ministry Of Health Information Directorate data. The secondary outcome measures are listed below. The first four measures are patient-reported outcomes from participants completing paper copies of the instruments.

-

(a) Hopelessness measured by the Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS) Reference Beck, Weissman, Lester and Trexler11 at baseline, 3 months and 1 year.

-

(b) Anxiety and depression measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) Reference Zigmond and Snaith12 at baseline, 3 months and 1 year.

-

(c) Quality of life as measured by the EQ-5D Reference Rabin and de Charro13 and the Social Functioning 36-item questionnaire (SF-36) Reference Ware and Sherbourne14 at baseline, 3 months and 1 year.

-

(d) Sense of belonging assessed by the Sense of Belonging Instrument – P Reference Hagerty and Patusky15 (range of scores from 18 to 72 with higher scores indicating lower belonging) and the Multi Ethnic Identity Reference Phinney16 measure at baseline, 3 months and 1 year.

-

(e) Self-reported repetition at 3 months and 1 year, assessed with a telephone questionnaire and a written questionnaire.

-

(f) Health service use at 3 months and 1 year assessed by a telephone questionnaire and interrogation of district health boards and Ministry Of Health Information Directorate records.

In addition to the outcome measures, the objective subscale of the Beck Suicidal Intent Scale Reference Beck, Morris and Beck17 was completed by all participants at baseline.

Analysis of the primary outcome was for all participants randomised. This analysis is likely to underestimate any effect of the intervention as it includes people who did not consent to take part in the study in the intervention arm who received only TAU. We therefore also analysed the primary outcome in those people who had consented to take part in the study. The secondary outcomes were analysed only in those people who had consented to be in the study.

For all participants TAU was assessed by self-report using a written questionnaire and telephone interviews at 3 and 12 months conducted by a research assistant; a review of district health board records; and by using the National Minimum Dataset from the Ministry of Health Information Directory to record hospital contacts and contact with mental health services. The National Minimum Dataset contains routinely collected information on all hospital discharges in New Zealand linked to a patient’s individual National Health Index number. The research assistants were masked to treatment allocation.

Sample size

We knew from our previous study that people who agree to receive PST have a hospital repetition rate at 1 year of about 13%. The rate of repetition in people who receive TAU is about 20% – that is a relative risk reduction of 35%, which would be clinically important. To detect such a difference with a two-sided 5% significance and a power of 80% power we calculated we needed to recruit 440 people into each arm of the trial.

Randomisation

As this was a Zelen trial, randomisation occurred prior to obtaining consent. All eligible participants were allocated randomly to the intervention or TAU groups using a central computerised randomisation system at the Clinical Trials Research Unit (subsequently the National Institute for Health Innovation http://www.nihi.auckland.ac.nz). Stratified minimisation randomisation was used to ensure a balance in key prognostic factors between the study groups: site (Waitemata, Counties Manukau, Northland and Waikato district health boards), history of self-harm (none, repeater) and method of self-harm (overdose, self-injury, both).

Statistical methods

Assessment of baseline comparability of the intervention and control group was carried out via descriptive analyses for demographic information, method of self-harm and previous history of self-harm. The number of re-presentation episodes per patient to hospital for self-harm during follow-up was analysed using negative binomial regression. Kaplan–Meier’s curves and Cox proportional hazards regression modelling was used to analyse time to first re-presentation to hospital for self-harm and time to event for the mortality outcomes. Categorical outcomes were compared between the groups using chi-squared test. The changes from baseline in each of the repeated continuous outcomes were analysed using mixed-model regression. ANOVA, t-tests, regression and non-parametric techniques were applied to other outcome measures depending on the distribution of the data.

Results

Recruitment and participant flow

The process of recruitment is shown in Fig. 1. Participants were recruited from August 2009 to May 2011 with follow-up ending in June 2012.

Fig. 1 Flow diagram of progress through trial

Baseline data

There were no statistically significant differences between those who consented and those who did not consent for age, gender or method of self-harm (Table 1). There was a significant difference in ethnicities between those who consented and those who did not. Pakeha (non-Maori New Zealanders) formed a significantly larger proportion of consenters whereas Asians formed a significantly larger proportion of non-consenters. People with a history of self-harm were significantly more likely to consent to the study than those who did not have such a history. There were no significant differences between those allocated to the two groups who provided consent to be in the study.

Outcomes

The use of health services for both groups are shown in Table 2. This shows that those people who received the ACCESS intervention received significantly more mental health face-to-face and telephone contacts than those in TAU group. This increase in the amount of contacts was mostly seen in people presenting with a repeat attempt. Participants who received the intervention were also significantly more likely to get any mental health intervention. It is also noteworthy that in the year after presenting with self-harm participants were more likely to attend a general hospital than a psychiatric hospital (this figure includes emergency department contacts for reasons other than self-harm). There were no significant differences in the proportion of people receiving psychiatric medication. None of the 47 Maori in ACCESS (whether in the intervention or control group) received follow-up from Maori mental health services.

In the intervention group 109 people (33%) received neither PST nor patient support; 27 (8%) received only patient support; 45 (14%) received patient support and attended one or two sessions of PST; and 139 participants (43%) received patient support and attended three or more PST sessions. Everyone in the intervention group received postcards.

The primary outcome of the proportion of people repeating and the number of episodes is shown in Table 3. There were no significant differences between those who received the intervention and those in the control group.

Time to first re-presentation for all randomised patients was analysed using Kaplan–Meier survival analysis and Cox proportional hazards regression modelling. The median follow-up duration was 365.25 days (range 0–365.25 days). The intention-to-treat analysis consisted of all patients that were randomised (intervention group (n = 737) v. TAU group (n = 737)) and showed there was no significant difference between the two groups in time to first re-presentation (log-rank test P = 0.6564). For participants who consented to take part in ACCESS (intervention group (n = 327) v. TAU group (n = 357)) the Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that was no significant difference between the two groups in time to first re-presentation (log-rank test P = 0.9178).

Participants who received PST repeated less often compared with those who consented to TAU and those who consented to the intervention but did not receive PST. However, none of the differences were statistically significant (Table 4).

A total of 27 people received patient support without any PST of whom 12 (44.4%) had repeated after a year. The mean number of sessions received by people who had any PST was 3.93 sessions (median 4, s.d. = 1.75) with a range of one to seven sessions.

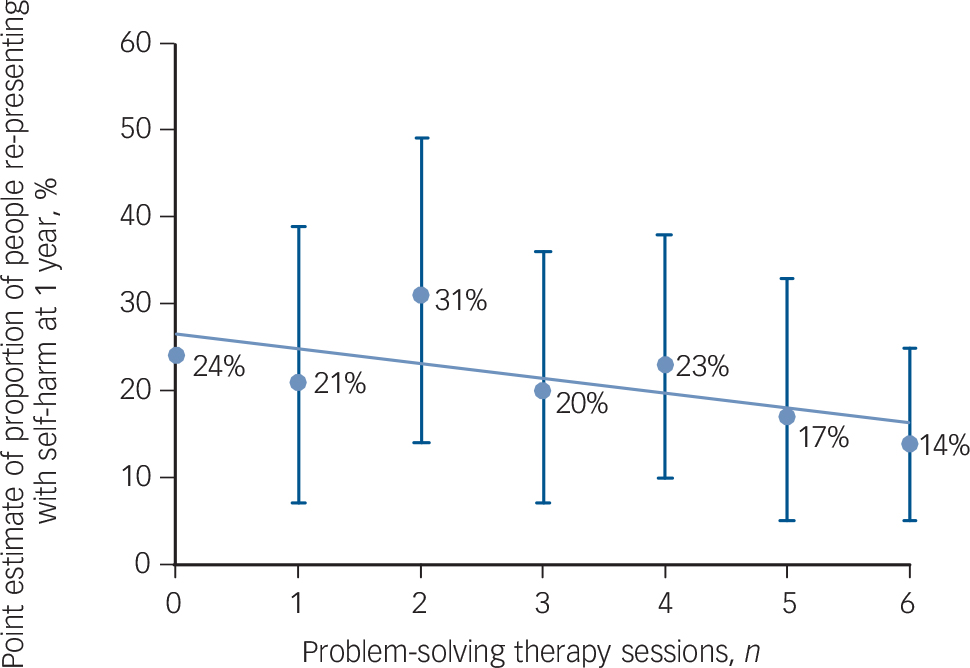

There appeared to be a relationship between the number of sessions of PST received and the proportion of people repeating with fewer re-presentations associated with increased number of sessions of PST (Fig. 2). For those participants who were most suicidal at initial presentation (scoring 6 or more on the objective subscale of the Beck Suicidal Intent scale) the proportion of people representing at 1 year in the intervention group was lower than in the control group but the difference was not significant (27 of 145 (18.6%) people re-presented in the intervention group v. 40 of 155 (25.8%) participants in the TAU group, a difference of 7.2% (95% CI −16.6 to 2.2, χ2 = 2.23, P = 0.14). Similarly the proportion of people repeating after 12 months did not differ between the two groups when the groups who consented were analysed by method of self-harm at the index presentation (53 out of 258 people (20.5%) who presented with an overdose of medication re-presented in the intervention group compared with 53 out of 274 (19.3%) participants in the control group (χ2 = 0.12, P = 0.73); 9 out of 58 people (15.5%) who presented with self-injury re-presented in the intervention group compared with 14 out of 67 people (20.9%) in the control group (χ2 = 0.60, P = 0.44)). The proportion of participants who re-presented after 1 year was no different between the intervention and control groups when those who consented were divided into those 25 years old and younger at the index presentation and those over 25 (20 out of 98 (20.4%) 25-year-olds and younger re-presented in the intervention group compared with 19 out of 106 (17.9%) in the control group (χ2 = 0.20, P = 0.65); 46 out of 229 (20.1%) participants over the age of 25 in the intervention group re-presented after a year compared with 54 out of 251 (21.5%) participants in the control group (χ2 = 0.15, P = 0.70)).

Data on continuous outcomes was collected for people who were randomised to the intervention group and consented (n = 327) and those who were randomised to the control group and consented (n = 357). Table 5 contains the summary information for each outcome by intervention group. At 1 year we were unable to collect data on these outcomes for about a third of each group. We found no significant differences between the groups on any of the continuous outcome measures at 3- or 12-month follow-up except for sense of belonging at 3 months and the multigroup ethnic identity measure at 1 year. To take into account any differences in baseline scores and missing data we also used a mixed linear model. The change from baseline in the continuous outcome measurement (at 3 months and 1 year) was analysed using mixed models in SAS v. 9.2 for Windows. Intervention × visit interaction effects were found to be non-significant (P≥0.05).

Discussion

In this large, Zelen multicentre RCT we were interested in whether a package of care resulted in better outcomes than usual care. We did not find significant differences in re-presentation rates to hospital for self-harm between the two groups in the intention-to-treat analysis of everyone randomised. Comparison at this level gives some indication of what the outcomes would be if this package of interventions was introduced at a service level although it is likely to underestimate any effects. Neither did we find an effect in the per-protocol analysis of everyone who consented to the intervention, which helps to answer the question about what would happen to individual patients if they agreed to have the package of care. Although there were 20% fewer episodes in the intervention group the difference was not statistically significant.

The rationale for the Zelen design in self-harm research is that the consent process is better suited to people in crisis and that it produces more representative groups of participants than standard RCTs. Reference Hatcher, Sharon and Coggan9 However, there are also significant disadvantages, the main one being that the analysis of only those who consent to take part in the study loses the benefits of randomisation in that the different groups may not be comparable for potential confounders. Nevertheless, analysis of only those who consent

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of patients by treatment and consent Footnote a

| Patients randomised and

consenting to intervention (n = 327) |

Patients randomised to control group (n = 357) |

Difference between patients who consented (n = 327 v. n = 357) P |

Patients randomised to

intervention who refused consent (n = 410) |

Patients randomised to control group who refused consent (n = 380) |

Difference between patients who

consented and those who refused consent (n = 684 v. n = 790) P |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years: mean (s.d.) | 37.5 (14.6) | 36.2 (14.2) | 0.25 | 34.9 (15.1) | 37.2 (15.7) | 0.29 |

| Women, n (%) | 212 (64.8) | 252 (70.6) | 0.11 | 268 (65.4) | 246 (64.7) | 0.26 |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | 0.94 | 0.01 | ||||

| New Zealand European | 258 (78.9) | 281 (78.7) | 286 (69.8) | 282 (74.2) | ||

| Maori | 24 (7.3) | 23 (6.4) | 22 (5.4) | 21 (5.5) | ||

| Pacific Island | 22 (6.7) | 23 (6.4) | 39 (9.5) | 20 (5.3) | ||

| Asian | 18 (5.5) | 22 (6.2) | 51 (12.4) | 46 (12.1) | ||

| Other | 5 (1.5) | 8 (2.2) | ||||

| First self-harm, n (%) | 151 (46.2) | 163 (45.7) | 0.89 | 218 (53.2) | 196 (51.6) | 0.01 |

| Type of self-harm, n (%) | 0.31 | |||||

| Overdose | 258 (78.9) | 274 (76.8) | 0.69 | 307 (74.9) | 291 (76.6) | |

| Self-injury | 58 (17.7) | 67 (18.8) | 90 (22.0) | 77 (20.3) | ||

| Both | 11 (3.4) | 16 (4.5) | 13 (3.2) | 12 (3.2) | ||

a. Results in bold are significant.

Table 2 Use of health services at 3 and 12 months Footnote a

| Intervention (n = 327) | Control (n = 357) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| From index episode to 3 months |

3–12 months |

From index episode to 3 months |

3–12 months |

Invention v. control

group at 3 months, P |

|

| Data from district health boards records | |||||

| Number of mental health face-to-face contacts, mean (s.d.) | 4.3 (7.6) | 5.4 (11.6) | 3.0 (5.2) | 4.9 (10.5) | 0.01 Footnote b |

| Face-to-face contact with alcohol and drug services, n (%) | 34/320 (10.6) | 32/318 (10.1) | 58/354 (16.4) | 48/351 (13.7) | |

| No recorded face-to-face mental health follow-up, n (%) | 125/320 (39.1) | 194/318 (61.0) | 165/354 (46.6) | 217/351 (61.8) | 0.05 Footnote c |

| No recorded face-to-face mental health follow-up by past history of self-harm, n (%) | |||||

| First time presentation | 68/146 (46.6) | 102/148 (68.9) | 80/158 (50.6) | 114/160 (71.2) | |

| Repeat presentation | 54/171 (31.6) | 92/170 (54.1) | 82/193 (42.5) | 103/191 (53.9) | 0.03 Footnote c |

| People admitted to a general hospital

after 1 year (includes emergency department contact for reasons other than self-harm), n (%) |

126 (39.6) | 130 (37.0) | |||

| Admissions to a general hospital after

1 year (includes emergency department contact for reasons other than self-harm), n |

301 | 350 | |||

| People admitted to a psychiatric hospital after 1 year, n (%) | 32 (10.1) | 36 (10.3) | |||

| Admissions to a psychiatric hospital after 1 year, n | 42 | 51 | |||

| Data from self-report | |||||

| Number of general practitioner contacts, mean (s.d.) | 2.5 (2.2) | 4.9 (5.6) | 2.9 (3.3) | 5.1 (11.3) | |

| Attended a general practitioner, n (%) | 171/227 (75.3) | 192/211 (90.9) | 181/258 (70.2) | 207/232 (89.2) | |

| Currently taking psychiatric medication, n (%) | 146/226 (64.6) | 111/211 (52.6) | 164/256 (64.0) | 132/232 (56.9) | |

| Currently taking psychiatric medication by history of self-harm, n (%) | |||||

| First time | 69/109 (63.3) | 42/95 (44.2) | 62/119 (52.1) | 44/105 (41.9) | |

| Repeat attempt | 77/117 (65.8) | 69/116 (59.5) | 102/137 (74.5) | 88/127 (69.3) | |

a. Median value for face-to-face contacts in both groups is 1 at 3 months and 0 at 3–12 months. Median value for telephone contacts in both groups is 2 at 3 months and 0 at 3–12 months.

b. Comparing intervention group with control group at 3 months using t-test.

c. Comparing intervention group with control group at 3 months using chi-squared test.

Table 3 Number (%) of participants re-presenting to hospital with self-harm and number of self-harm episodes re-presenting to hospital

| n (%) | Risk difference, % (95% CI) |

n (%) | Risk difference, % (95% CI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consented to intervention group |

Consented to control group |

All randomised to intervention group |

All randomised to control group |

|||

| At 3 months | ||||||

| All index episodes | ||||||

| Participants re-presenting | 47/327 (14.4) | 42/357 (11.8) | 2.6 (–2.5 to 7.7) | 86/737 (11.6) | 75/737 (10.2) | 1.5 (–1.7 to 4.7) |

| Episodes re-presenting | 60 | 62 | 114 | 108 | ||

| Index episode is first self-harm episode | ||||||

| Participants re-presenting | 16/151 (10.6) | 10/163 (6.1) | 4.5 (–1.7 to 10.6) | 23/369 (6.2) | 16/359 (4.5) | 1.7 (–1.5 to 5.0) |

| Episodes re-presenting | 19 | 16 | 27 | 22 | ||

| Index episode is repeat episode | ||||||

| Participants re-presenting | 31/176 (17.6) | 32/194 (16.5) | 1.2 (–6.6 to 8.8) | 63/368 (17.1) | 59/378 (15.6) | |

| Episodes re-presenting | 41 | 46 | 87 | 86 | ||

| At 12 months | ||||||

| All index episodes | ||||||

| Participants re-presenting | 66/327 (20.2) | 73/357 (20.4) | –0.2 (–6.3 to 5.8) | 142/737 (19.3) | 135/737 (18.3) | 1.0 (–3.0 to 4.9) |

| Episodes re-presenting | 129 | 163 | 256 | 272 | ||

| Index episode is first self-harm episode | ||||||

| Participants re-presenting | 19/151 (12.6) | 17/163 (10.4) | 2.2 (–4.9 to 9.2) | 39/369 (10.6) | 40/359 (11.1) | –0.5 (–5.1 to 4.0) |

| Episodes re-presenting | 29 | 31 | 54 | 55 | ||

| Index episode is repeat episode | ||||||

| Participants re-presenting | 47/176 (26.7) | 56/194 (28.9) | –2.2 (–11.3 to 7.0) | 104/368 (28.3) | 95/378 (25.1) | 3.1 (–3.2 to 9.5) |

| Episodes re-presenting | 100 | 132 | 202 | 217 | ||

Table 4 Number (%) of participants re-presenting to hospital with self-harm at 12 months by treatment received

| Consented to intervention | Control groups | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Did not receive PST or patient support |

Received any

PST |

Completed PST plus patient support |

Completed PST, received patient support and used GP voucher |

Consented to control |

All randomised to control |

|

| All Index episodes, n (%) | 20/109 (18.3) | 33/185 (17.8) | 22/139 (15.8) | 11/65 (16.7) | 73/357 (20.4) | 135/737 (18.3) |

| Index episode is first self-harm episode, n (%) | 4/44 (9.1) | 11/92 (12.0) | 7/72 (9.7) | 3/33 (9.1) | 17/163 (10.4) | 40/359 (11.1) |

| Index episode is repeat episode, n (%) | 16/65 (24.6) | 22/93 (23.7) | 15/67 (22.4) | 8/33 (24.2) | 56/194 (28.9) | 95/378 (25.1) |

PST, problem-solving therapy.

provides valuable information about acceptability of treatment and the influence of patient preference on outcomes.

Possible explanations for our findings

There are several possibilities for the lack of an effect in this study. First, is the issue of power. We recruited fewer patients than we planned. The 95% confidence intervals around the primary outcome measure of re-presentation to hospital with intentional self-harm after 12 months show a range of about –5% to 5%, which indicate that larger clinically significant effects were unlikely to have been missed.

Next is the issue of engagement in treatment. In total 34% of consenting participants received neither patient support nor PST so the intervention they received was limited to receipt of postcards and for some, use of the GP voucher. Although all consenting participants were offered the GP voucher, uptake was generally low with only 36% of participants using their voucher.

The ‘dose’ of PST was low. People were offered four to six sessions of PST but only 43% attended three or more sessions. A common reflection by the clinicians and patients was that more sessions of PST, specifically the addition of one or more booster sessions in the months following the initial therapy would have been beneficial. This may explain why we found an effect of PST in our previous study, Reference Hatcher, Sharon, Parag and Collins3 which used six to eight sessions of therapy (mean number of sessions of PST was six) but not this study where the dose was smaller (mean number of PST sessions four). It is noteworthy that there appeared to be a dose-response relationship with people who had more PST repeating self-harm less frequently.

A problem with research in this area is the need to get individual consent to participate in the study. This significantly delays the start of treatment when people are in crisis, interferes with engagement and probably leads to an underestimation of the effects of any intervention. Future self-harm intervention studies should consider using a cluster randomised control design. As well the artificial barrier introduced by the consent process it is clear from the literature that it is difficult to engage patients in treatment after coming to hospital with self-harm. However, in the intervention arm of this study patients did receive significantly more treatment than usual compared with the control group, which suggests that the ‘patient support’ element of the intervention had some effect. There is also a suggestion that the package was more effective in people who made more serious suicide attempts at initial presentation.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence NICE guidelines on the longer-term management of self-harm, 18 which focused on care after the first 48 h of an episode of self-harm were published in November 2011 and systematically reviewed the literature on interventions until January 2011. The conclusion was there was some evidence of clinical benefit of psychological interventions, which included cognitive behavioural, psychodynamic and PST, compared with routine care although most of this evidence comes from studies where the comparison group has a

Fig. 2 Point estimate with 95% confidence intervals of proportion of people re-presenting with self-harm to hospital at 1 year by number of problem-solving therapy sessions.

high rate of repetition (for example Brown et al Reference Brown, Ten Have, Henriques, Xie, Hollander and Beck19 ). Our previous study was an attempt to address this gap and showed that PST was ineffective for all episodes of self-harm although in the subpopulation whose index episode was a repeat, PST reduced the proportion of people repeating self-harm at 1 year (relative risk 0.39, 95% CI 0.07–0.60, number needed to treat, 12,

Table 5 Continuous outcome measures

| Consented to intervention (n = 327) | Consented to control (n = 357) | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean (s.d.) | n | Mean (s.d.) | ||

| Beck Hopelessness Scale | |||||

| Baseline | 300 | 11.1 (6.2) | 331 | 11.3 (6.1) | |

| 3 months | 211 | 8.4 (6.7) | 243 | 9.4 (6.4) | |

| 1 year | 210 | 8.3 (6.3) | 233 | 8.4 (6.4) | |

| Change: baseline to 3 months | 198 | –2.8 (6.3) | 235 | –2.2 (5.4) | |

| Change: baseline to 1 year | 195 | –3.2 (6.7) | 219 | –3.0 (6.4) | |

| EQ-5D descriptive score | |||||

| Baseline | 319 | 8.0 (1.9) | 349 | 7.8 (1.8) | |

| 3 months | 223 | 7.4 (1.9) | 257 | 7.4 (1.9) | |

| 1 year | 211 | 7.4 (1.8) | 235 | 7.1 (1.8) | |

| Beck Suicide Intent Scale – objective subscale | |||||

| Baseline | 316 | 5.3 (3.0) | 351 | 5.3 (3.1) | |

| SF-36 physical | |||||

| Baseline | 311 | 47.7 (12.2) | 347 | 49.0 (11.2) | |

| 3 months | 209 | 47.5 (11.9) | 246 | 48.5 (11.4) | |

| 1 year | 210 | 48.8 (11.0) | 234 | 48.6 (10.8) | |

| SF-36 Mental | |||||

| Baseline | 311 | 19.4 (12.8) | 347 | 19.9 (13.8) | |

| 3 months | 209 | 31.8 (15.8) | 246 | 28.8 (16.4) | |

| 1 year | 210 | 31.0 (16.5) | 234 | 32.9 (17.0) | |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale – depression subscale | |||||

| Baseline | 320 | 9.9 (2.0) | 352 | 9.9 (2.1) | |

| 3 months | 224 | 7.6 (5.2) | 256 | 8.0 (5.0) | |

| 1 year | 211 | 6.8 (4.9) | 234 | 6.5 (5.1) | |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale – anxiety subscale | |||||

| Baseline | 320 | 13.2 (4.2) | 351 | 13.0 (4.7) | |

| 3 months | 224 | 10.5 (5.2) | 255 | 11.1 (5.1) | |

| 1 year | 211 | 10.6 (4.8) | 234 | 10.1 (5.1) | |

| Sense of Belonging Instrument | |||||

| Baseline | 320 | 46.6 (12.5) | 354 | 46.9 (12.7) | |

| 3 months | 226 | 42.1 (13.5) | 260 | 44.6 (12.8) | 0.03 |

| 1 year | 211 | 41.3 (13.3) | 234 | 43.0 (13.2) | |

| Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure | |||||

| Baseline | 313 | 14.6 (4.0) | 347 | 14.1 (4.2) | |

| 3 months | 220 | 14.2 (4.4) | 254 | 14.8 (3.9) | |

| 1 year | 211 | 14.1 (4.1) | 234 | 14.9 (3.8) | 0.05 |

P = 0.03). Reference Hatcher, Sharon, Parag and Collins3 Since then there have been several published RCTs relevant to the treatment of self-harm in people who present to emergency departments that have shown small or no effects of different interventions on suicidal behaviour. Reference Morthorst, Krogh, Erlangsen, Alberdi and Nordentoft20–Reference Hvid, Vangborg, Sørensen, Nielsen, Stenborg and Wang24

Implications

People who present with self-harm to emergency departments are a heterogeneous population and thinking that one intervention would be effective for everyone is probably naive. Consideration should be given to different interventions for people presenting to hospital for the first time and repeaters. It appears that unless the comparison group has a high rate of repetition that the effectiveness of psychological therapies and assertive follow-up is of limited effectiveness following self-harm. Currently PST of six to eight sessions, possibly with booster sessions and patient support should be limited to people with a history of self-harm. In people with borderline personality disorder who present to hospital with self-harm DBT can be helpful. Reference Stoffers, Vollm, Rucker, Timmer, Huband and Lieb25 The risk management strategy needs to be tested in a stand-alone study.

More research needs to be done about the role of cultural assessment after people present with self-harm and potential therapeutic options in this area in mainstream populations. Given the low risk of adverse events it would seem reasonable to recommend postcards pending further evaluation. It is too early to say whether this should also be combined with improved access to family doctors in an attempt to reduce the non-mental health increase in morbidity and mortality. There is a high rate of mental disorder in this population, Reference Hawton, Saunders, Topiwala and Haw26 which needs to be identified and treated although engagement in therapy can be difficult. Finally there is some evidence that using low-dose ketamine as a treatment for suicidal ideas Reference Larkin and Beautrais27 may have some merit although there are concerns about how long the effects last and the potential adverse effects.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.