13.1 Introduction

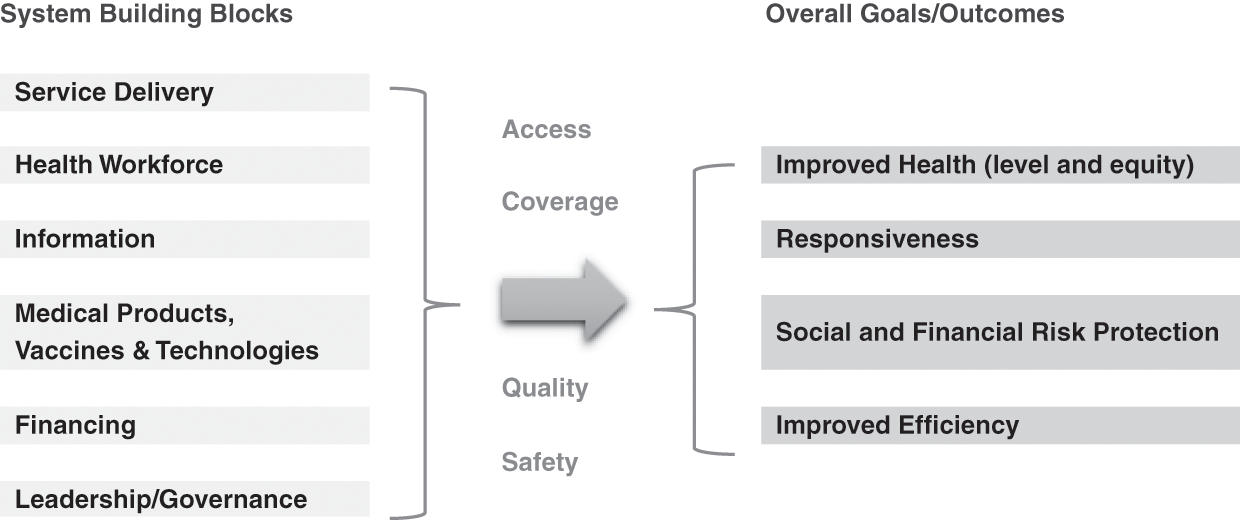

Section II of this book analysed the evolution of the Malaysian health system over 60 years. Using the World Health Organization (WHO) health systems framework (World Health Organization, 2007) as a starting point, we analysed the interactions and feedback loops between the so-called building blocks of the health system and traced the evolution in terms of access, equity, quality and safety, and outcomes in terms of health status, financial protection and client satisfaction (Figure 13.1).

Recognising the limitations of the WHO framework, this chapter sets out to identify the key messages and lessons that cut across the individual chapters of this book. In doing so, it seeks to illuminate the multi-directional interactions between the various building blocks of the WHO health system framework and the interaction between the health system and its context in understanding the story of Malaysia’s health system and its future challenges.

The chapter begins with a discussion of the context of Malaysia’s health system and its importance to health systems development and evolution. Next, it focuses on the health system, including its different building blocks, and seeks to identify lessons from the historical evolution of Malaysia’s health system. It then goes on to look at more recent developments and the current challenges facing both the healthcare system and the state of population health. Finally, the chapter provides a critique of the WHO health systems framework and proposes a set of generic issues that may be relevant to other countries who wish to analyse their own health systems.

13.2 The Importance of Context

As noted in Chapter 1, health systems are situated within a wider social, political, economic and geographic context. Furthermore, as open systems, they interact with this context and its changes and transitions over time. The health needs and expectations of the population are part of this context, and they too evolve over time to place changing demands on the health system. The importance of the inter-relationships between the health system, its context and the population is evident from Malaysia’s experience as well as from a consideration of the future challenges to the health system.

For example, Malaysia’s relative political stability and rapid social and economic development after independence were important in providing the basis for rapid improvements in health and the emergence of an effective health system. Sustained long-term economic growth, steady progress in poverty reduction and improvements in education were important contextual factors that not only improved health but also helped generate public revenue (from a mix of taxes, the sale of natural resources, and state-owned industries) with which to build a health system and allow many services to be provided free at the point of use. With a growing economy, total health expenditure (THE) has been able to consistently grow in both relative and absolute terms (Chapters 3 and 9 provide details).

Another important contextual factor, especially in the first few decades after independence, was the interventionist role played by the government in social and economic development. This included the government playing a central and proactive role in the building of a national health system as part of a wider nation-building exercise. The Ministry of Health (MoH), in particular, led a successful supply-led approach to health systems development that involved the production and deployment of health personnel across the country; the building and improvement of clinics and hospitals; and the establishment of disease control, family planning and nutrition supplementation programmes (Reference Suleiman and JegathesanSuleiman & Jegathesan, n.d.). Chapters 4–8 and 10–12 provide details.

The government also played a critical role in shaping an approach to health improvement that was appropriate and effective (this approach was similar to but preceded the Primary Health Care Approach codified by the WHO at the 1978 Alma Ata Conference). This included ensuring effective multi-sectoral collaboration and community engagement, developing human resources that were affordable yet effective in delivering prioritised, simple but effective interventions such as growth monitoring, effective oral rehydration techniques, breastfeeding support, basic immunisation coverage, female literacy, school health, family planning, food and nutrition, and water and sanitation programmes (Chapters 4, 6, 7 and 8 provide details). As a modern and predominantly urbanised upper-middle-income country with a high human development index (United Nations Development Programme, 2018), Malaysia has now met most basic needs.

However, the role of the state in driving socio-economic development has become less central in more recent decades. Malaysia is now part of a more liberalised and integrated world economy that has shifted many governments towards encouraging greater marketisation, consumer choice and privatisation across society. As a consequence, although the government still produces five-year plans with explicit social and human development objectives, its role relative to that of markets and the private sector has diminished.

This shift in approach with respect to the health sector was first expressed explicitly in the Fifth Malaysia Plan, which noted the limited financial capacity of the public sector and the need for wealthier households to make direct contributions towards the cost of their own healthcare (Prime Minister’s Office, Malaysia, 1986). Private health finance has subsequently risen from being about 25% of THE in 1983 (Westinghouse Health Systems, 1985) to now being about 50% of THE (Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2017), and the role of private providers has similarly grown in the health system.

Another important contextual variable is the population served by health systems and for whom they provide services. In some instances, the population directly influences the health system. For example, urbanisation and a growing upper and middle class with increasing levels of disposable household income helped create a greater demand for private healthcare and more sophisticated secondary and tertiary services (Chapters 5 and 9 provide details). In other instances, demographic, epidemiological and nutrition transitions have required the health system to evolve and respond to new challenges such as the growing prevalence of chronic diseases and a rising prevalence of conditions of old age (Chapter 6). Similarly, the growing number of migrants in Malaysia (documented and undocumented) is posing several new challenges to the health system (Chapter 3).

13.3 Achieving Universal Health Coverage: Lessons Learnt

Malaysia has to a great extent attained the goal of achieving universal health coverage (UHC), especially in relation to meeting basic needs and ensuring that all Malaysian citizens and permanent residents have access to essential and affordable healthcare (Reference Ng, Mohd Hairi, Ng, Kamarulzaman, Tey, Cheong and RasiahNg et al., 2016; World Health Organization Western Pacific Region, 2018). Although all countries face the challenge of continually expanding the depth and breadth of UHC coverage while also extending financial protection, a number of lessons can be learnt about Malaysia’s past success.

To begin, during the first four decades after independence, improvements in health were largely the consequence of broader socio-economic development and a commitment to reducing disparities within the country. Improvements in water and sanitation, nutrition status and literacy not only improved living standards but also contributed to reductions in mortality and morbidity. Developments of the health system also made important contributions to health improvement by rapidly increasing vaccination coverage, reducing maternal mortality from obstetric causes of death, improving completed tuberculosis (TB) treatment rates and providing access to essential drugs and vaccines.

Importantly, the health system improved health in ways that were efficient and equitable. Efficiency can be seen from the relatively low levels of THE. For example, in 1973, during the phase of rapid health system development and declining mortality and morbidity, THE was still only about 2% of the gross domestic product (GDP), two-thirds of which was spent in the public sector (Reference RoemerRoemer, 1985). A notable aspect of the early history of health systems development in Malaysia was the active targeting of investments and services towards the poorer and rural communities of the country, which produced notable reductions in geographic and socio-economic disparities in health (Chapter 3 provides details).

But what can be learnt from the experience of Malaysia about how the building blocks of the health system combined to improve health? We have drawn five key lessons from it.

The first lesson is that governance and leadership played a central role, especially during the early decades when public sector financing enabled the government to build the human and physical infrastructure of the health system. The health system was predominantly public in nature. The MoH played a particularly important role in implementing a set of supply-side interventions to increase population coverage of key programmes and services. Crucially, the supply-side ingredients of the health system were combined with community engagement and an appropriate mix of vertical and horizontal programmes. For example, effective community mobilisation by allied environmental health officers and technical expertise from engineers trained in public health are credited as two key factors in the success of the rural water supply and sanitation programme (Chapter 7 provides details). Similarly, the provision of credible and easily accessible basic obstetric care, with prompt and effective referral mechanisms for obstetric complications, combined with partnership with traditional birth attendants are credited for the rapid reduction in maternal mortality (Chapter 4). All of these services were provided free to the clients.

A corollary to governance and leadership was that the system was sufficiently flexible to enable leadership to modify the course of development in response to feedback. For example, after 15 years of investment in expanding the rural health infrastructure, the MoH commissioned a community survey that showed that a high proportion of rural villages remained under-served (Reference NoordinNoordin, 1978). This resulted in a change in policy to focus on the rapid production and deployment of community nurse-midwives and nurses, rather than awaiting the slower pace of construction of new rural health facilities (Chapter 4).

The second lesson is that while governance and leadership were important, effective management was critical, especially in relation to the operational building blocks. For example, of particular importance to the successful and rapid expansion of health services was the development and implementation of strategic health workforce development plans. Chapter 8 describes how the key ingredients were the production and use of an appropriate mix of health workers, including allied health workers, and the provision of non-financial incentives to help ensure good retention rates (especially in remote and rural areas) and high levels of morale and motivation. For example, because the rapidly expanding rural health programmes needed large numbers of new health workers close to rural communities and because the interventions needed were not technically complex, the MoH concentrated on producing allied health personnel.

Indeed, task shifting has been successfully practised in all phases of development, in accordance with service needs and accompanied by on-the-job training (e.g. surgical and anaesthetic procedures by medical assistants, emergency obstetric care by nurse-midwives, renal dialysis by nurses). Career and service development pathways were also integrated into workforce plans so that the workforce expanded and became increasingly skilled and specialised as the scope and quality of services improved (Chapter 8).

Similarly, there were well-designed plans for expanding healthcare infrastructure and promoting equitable access to speciality services. Chapter 5 describes the case of hospitals, where the MoH adopted a systematic approach based on regionalisation, with all hospitals categorised into one of three levels: Level 1 consisted of five basic specialities; Level 2 had six additional specialities; Level 3 consisted of sub-specialities (e.g. cardiologists and neurologists within the broader specialism of internal medicine).

Since independence, concerns regarding social and living conditions resulted in regular population surveys, complemented by reliable population and vital statistics, to monitor progress, at least in Peninsular Malaysia where most people lived. The early establishment of a health and management information system and the recognition of the importance of data also allowed the MoH to monitor and evaluate indicators of access, utilisation and health outcomes across rural and urban areas and between the different ethnic communities of the country. Chapter 10 illustrates how the MoH used a variety of sources such as routine data, supplementary surveys, research and evaluation, complaints and surveys of satisfaction, and media feedback. It also used different types of information, such as digitalisation, national health accounts and technology assessment, to support decision-making. The willingness and ability of policymakers and managers to use data and information, including community feedback, to refine or shift their strategies and plans was key to the success of many programmes.

Part of this success came from paying attention to developing managerial competency. Management training programmes were established from the very beginning for national, state, and district and facility managers. This was also accompanied by the appropriate devolution of decision-making to enable leadership development at all levels. Chapter 12 describes how attention was also paid to senior leadership training and competence. Appointment to senior posts within the MoH followed structured career development pathways that required prior management experience at different levels of the health system so that senior personnel could draw from a wide range of experience and a network of former colleagues and contacts. The early emphasis on managerial competencies later evolved into the development of formal institutes of training with good international reputation, including the National Institute of Public Administration (known as INTAN) and the Institute of Health Management.

The third lesson is that many of the successes in the development of the health system arose from incremental and steady improvements and the avoidance of sudden and radical reforms. Improvements were both incremental and phased through a set of sensible and logical steps. This slow but steady and incremental approach made it easier for the different building blocks of the health system to establish positive synergies with each other. Chapters 4 and 5 describe how this approach enabled the development of mutually beneficial relationships between the primary, secondary and tertiary levels of the system, and Chapters 6 and 7 describe how it enabled the integration of vertical disease control programmes and environmental health services into the rest of the health system.

Low dependence on foreign funding sheltered domestic policies and considerations from the influence of the vagaries of donor-driven agendas. However, a desire for international recognition meant a willingness by the MoH to use external expertise strategically to build local expertise in a way that avoided overdependence on foreign expertise.

It is possible to discern a common stepwise pattern in the development of the different components of the health system: progression from first improving access to healthcare, then improving quality and efficiency, to optimising the features of health systems responsiveness. For example, Chapter 11 describes the case of medicines, vaccines and technologies. The initial emphasis was on establishing secure and efficient storage, supply and distribution systems. This was followed by developing the infrastructure to test and monitor the quality and safety of medicines, for example, through adverse event monitoring. Subsequently, attention focused on issues such as price and cost control, for example, through the local production of generics and the use of international price referencing, bulk procurement and TRIPS (the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights) exemptions.

A similar pattern can be seen in the case of Malaysia’s rapid reduction of maternal mortality rates, which has been hailed as an international success story. Having established a national commitment to reducing maternal mortality rates, plans and strategies were established to first increase the supply and availability of skilled birth attendants and safe birth facilities. This was accompanied by a systematic stepwise service improvement plan that incorporated engagement with communities, including partnerships with traditional birth attendants and respect for non-harmful traditional practices, and the use of health service– and population-based information systems to monitor the quality and impact of maternal healthcare (Reference Pathmanathan, Liljestrand, Martins, Rajapaksa, Lissner and de SilvaPathmanathan et al., 2003) (Chapter 4).

The fourth lesson is that organising the health system around a set of clearly demarcated and contiguous geographic units was an important basis for effective health management, monitoring and evaluation. For example, the rural health service (RHS) was built around a number of basic units (health centres and satellite community clinics), each intended to serve 50,000 population. Each health district had a number of such configurations and a district hospital that embodied primary healthcare (PHC) principles in that the hospital provided support for national disease control programmes such as those for malaria, TB and leprosy and for the rural health services. Ambulances ferried patients, staff and laboratory samples and linked primary and secondary levels of care. The progress in infrastructure development as well as the performance of health programmes was monitored on a district-by-district basis in a way that commanded the attention of politicians and civil service administrators at all levels of national and state government.

The fifth lesson is that adequate public financing, enabled by a progressive tax-funded system, was important (Chapter 9). It not only paid for the development of the health system’s infrastructure but also allowed services to be provided free at the point of use for the large segments of the population living in poverty or on low incomes. Furthermore, because the health system was predominantly financed by public revenue, developments were able to take advantage of economies of scale and the government was able to play an unencumbered governance and leadership role. By contrast, the growth of private finance and private provision in more recent decades has compromised the government’s ability to manage the performance of the health system as a whole.

13.4 Achieving UHC: Current and Future Health Systems Challenges

Achieving UHC is not necessarily synonymous with sustaining it over time or in the face of new challenges. In fact, all health systems are faced with new challenges even while improvements in health status are being made. While earlier sections have told the story of Malaysia’s rapid improvements in health and access to healthcare, some data suggest that population health improvements have stalled and plateaued. There are also data indicating that levels of avoidable mortality are higher than in comparator countries (Ministry of Health Malaysia & Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, 2016). Furthermore, a set of new and emerging health challenges threaten to bring the ‘success story’ of Malaysia’s health system into question.

In this section, we summarise our analysis of two broad health systems issues as they relate to the health challenges facing the country. These issues are evident in all the chapters that describe the Malaysian experience. The first is the relationship between the public and private sectors. Although the WHO building blocks framework ignores the public–private mix as a dimension of a health system, it is critical to understand how public–private interactions impact on each other and on the health system as a whole. The second is the set of challenges facing the public sector specifically.

13.4.1 The Public–Private Mix

Malaysia’s health system has evolved from one that had been predominantly driven by the public sector to one in which the private sector and market are more prominent. The evolution began passively, mainly with the growth of private general practitioner (GP) clinics in urban areas and growing demand from an increasingly affluent segment of the population that sought to bypass waiting times and overcrowded facilities in the public sector. This was followed later on by specialist doctors leaving the public sector and helping to grow a private secondary and tertiary care (STC) sector.

However, in recent decades, the government has also actively encouraged private sector growth, especially in STC (Reference Chee, Barraclough, Chee and BarracloughChee & Barraclough, 2007; Reference CheeChee, 2008). For example, the government has enabled private sector workers to use some of their social security contributions to purchase private healthcare (Reference NgNg, 2005) and has allowed for private medical expenses and the purchase of voluntary health insurance to be tax-deductible (Reference Chee, Barraclough, Chee and BarracloughChee & Barraclough, 2007). Private finance makes up approximately half of THE, mainly from out-of-pocket payments (OOPPs) made to the private sector (Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2017).1

Finance capital investment in the health sector has been another driver of the growth of the private STC sector and the fact that profit-maximising corporations mainly own private hospitals. A significant amount of finance capital in Malaysia comes from sovereign wealth funds. Many private hospitals are thus wholly or partially owned by government-linked companies (GLCs).2 The proportion of all acute hospital beds in private hospitals grew from 5.8% in 1980 to 27.3% in 2017, and about 30% of all acute hospital admissions now occur in private hospitals (Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2018b). However, GLCs own more than 50% of private hospital beds, supporting the government’s interest in seeing private hospitals maximise profits. More recently, this has included the growing market in health tourism (Reference Ng, Barber, Lorenzoni and OngNg, 2019).

Within this context, the rapid growth of private medical and nursing schools is noteworthy (Chapter 8). Similarly, the outsourcing of public services (e.g. clinical waste management, renal dialysis, sewage and sanitation, air quality monitoring (Chapter 7), and pharmaceuticals procurement, supply and distribution (Chapter 11)) to private enterprises are indications of this trend.

Passive and active privatisation has thus been an important aspect of health system development in the past 30 years or so; inevitably, this raises questions about the impact it has had on the health system. As previously noted, some aspects of privatisation are viewed as success stories, mainly in relation to unlocking capital investment through the outsourcing of certain services and functions. It is also argued that private finance has increased overall health expenditure, that private providers have reduced the burden of care in the public sector, and that consumer choice and market competition have improved patient satisfaction and quality and helped contain costs.

Equally, there are some concerns about the public–private mix. The high level of OOPPs suggests that health finance may not be progressive and that user fees could limit access to healthcare. In reality, free or low-cost public sector hospital and outpatient services appear to have avoided significant financial barriers to healthcare and helped keep levels of catastrophic health expenditure (CHE) low in Malaysia (Chapter 9).3

However, a tiered system of healthcare has emerged, with the lower-income population groups being disproportionately reliant on the public sector for ambulatory and inpatient care. In comparison, wealthier sections utilise the private sector (Health Policy Research Associates et al., 2013). This runs the risk of widening the social inequalities in health by institutionalising a lower-quality public service for the poor and a better-resourced private sector for the wealthy. For example, we already see a proliferation of high-cost technology and a higher concentration of STC in the more affluent regions of the country (Reference Suleiman and JegathesanSuleiman & Jegathesan, n.d.). This is one of the reasons the health system as a whole has become unbalanced, with a disproportionately high level of expenditure at STC level (Reference Suleiman and JegathesanSuleiman & Jegathesan, n.d.).

Some aspects of the public–private mix are also likely to produce health sector inefficiencies. For example, the high level of OOPPs in the STC should raise concerns about the potential for market failures and high levels of supplier-induced demand for unnecessary or overpriced healthcare. Commercial pressures may also result in cost-cutting and compromises on the quality of care, or the private sector cherry-picking profitable elements of healthcare while leaving the public sector to look after patients and conditions that are unprofitable. Additionally, the private sector can drain the public sector of human resources that are in short supply, most notably medical specialists.

Elsewhere in the health system, the multiplicity of primary care providers, including private GPs, pharmacies, specialist practitioners and traditional medicine providers competing with each and with public sector clinics, results in healthcare provision being fragmented, inefficient and characterised by poor continuity of care as patients hop between different providers. The lack of communication and effective referral systems between private primary care providers and STC facilities are not only another example of fragmentation but also an indicator of substandard and inefficient care. The lack of co-ordination between the public and private sectors is also evident in the mismatch between the production of new medical and nursing graduates by private institutions and the lack of post-graduate training and employment opportunities in the public sector. Another example is the financial barrier to patients coming from the private sector to the public sector.

For any health system to function optimally, the public and private sectors need to work in a co-ordinated and positively synergistic manner. But for this to happen, regulation is required to correct any market failures that may emerge within the system and to ensure that private actors have the right mix of incentives and sanctions to prevent unwanted behaviour. It is also necessary to be able to monitor and evaluate the nature and impacts of the public–private mix. Thus, for both the primary and the STC sector, the general direction of travel should be towards improving data and knowledge on the public–private dynamics within the health system and subsequently implementing regulations to optimise health systems performance.

The first concerns the fragmentation and inefficiency of the primary care system and the fact that private primary care providers could be deployed to deliver more cost-effective care. Some improvements could be made by adjusting the fee schedule for private GPs so that they would be incentivised to spend time and effort on health promotion while also ending their over-reliance on the dispensing of medicines for their income. Requiring private primary care providers to adhere to a national health and management information system (HMIS) would also make it possible for primary care to be adequately monitored and evaluated. A more ambitious aim would be to incorporate private GPs into public service contracts by which they would form part of a single and integrated primary care system that would include public sector services.

Regarding the STC sector, better data and information are required to help us understand the quality, safety and outcomes of care in private hospitals. In addition, the tension between the government’s economic objectives – increasing foreign income from medical tourism and ensuring healthy returns to the state’s investment in private hospitals – and its social goals of providing practical, equitable and efficient healthcare for all may need to be assessed and addressed more explicitly.

The third issue relates to the need for better alignment between the production of new health workers, driven by a growing number of private institutions, and the design and implementation of a medium- to long-term health workforce plan based on projected population health and health systems needs. Ideally, both public and private institutions producing new health workers will be responsive to the workforce needs of the health system, rather than the health system being expected to accommodate the training and career development needs of students and graduates. A related concern is the government encouragement of the development of education in the private sector, including education of health professionals, partly as an export industry. Limited capacity to cope with related internships has led to problems in providing quality supervision (Reference Wong and Abdul KadirWong & Abdul Kadir, 2017).

The final issue concerns medical inflation or the propensity for healthcare costs to keep growing due to costly medical and technological advancements and because of the growing number of people living with chronic medical conditions. Rising healthcare costs not only result in pressures on government and household budgets but may also increase disparities in access to healthcare due to wealthy households being able to afford the higher costs of medical care. While medical inflation is a global challenge for the health sector as a whole, it is particularly important to regulate private sector actors that have an interest in encouraging medical inflation. Of particular importance is the need to engage with trade-related policies and laws that govern the price of medicines and other technologies and that set limits on the abilities of governments to regulate markets and market actors.

13.4.2 Public Sector Strengthening

The MoH has a long and impressive track record of ensuring that the public sector works effectively and efficiently. Furthermore, although the private sector consumes nearly half of THE, the public sector is the largest provider of inpatient and ambulatory care, employing 65% of all doctors and 76% of all nurses in 2015 (Planning Division, MoH, 2016). Together with the fact that it has the primary responsibility of managing public health threats, these are clear reasons why a well-performing public sector is essential.

One aspect that needs attention concerns public financing. Presently, public revenue as a proportion of the GDP is declining in Malaysia and is low compared to other upper-middle-income countries (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2019). This places constraints on government health budgets and the MoH’s ability to strengthen the public sector healthcare system. The reason for the reduction in public sector revenue (as a proportion of GDP) is not apparent.

Another issue requiring attention relates to the health challenges associated with rapid (and thereby informal and less well-planned) urbanisation. The challenges include a higher proportion of undocumented residents who may be living in poor and crowded conditions, a lack of healthcare organisation with services being more fragmented, higher levels of population mobility, and increased susceptibility to disease outbreaks. While there are good data on disparities between states, monitoring systems have been slow to adapt to the challenges posed by rapid urbanisation. Currently, with 70% of the population living in urban configurations, information systems are not sufficiently sophisticated for monitoring social inequities in health and being able to identify high-need households and communities. Thus, for example, the routine nationwide monitoring of childhood nutrition status was unable to pick up the high prevalence of childhood stunting in dwellers in urban low-cost housing in one city (United Nations Children’s Fund, 2018).

In terms of the challenges of improving the overall performance of the public sector, the MoH is already implementing several initiatives such as developing multi-disciplinary health centres to provide cost-effective and seamless preventive and curative care in ambulatory settings (within family and community perspectives). However, to really enable the critical role of PHC within the health system, levels of PHC spending will need to increase. It is estimated that only 17% of THE is spent on primary care (Ministry of Health Malaysia & Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, 2016) and that public expenditure on primary care is even lower (only 11% compared to 65% on STC). The need to strengthen PHC is highlighted by a study that found that the prevalence of hypertension and diabetes among adults was 30.3% and 17.5%, respectively (Institute for Public Health, 2015), with about half of these adults being unaware of their condition.

Another issue is the significant underutilisation of small district hospitals with bed occupancy rates below 50%. The reasons for this are both the overprovision of hospital beds in some cases and the scale of operation of small hospitals that limits their capacity to provide more critical services and updated surgical practices. Recent experience with clustering some smaller hospitals with larger ones for the provision of elective surgery in the smaller hospitals increased the occupancy rates of the smaller hospitals slightly from an average of 48% to only 54% (Institute of Health Management, 2017). While the use of telemedicine and the pooling of budgets and management through the formation of hospital clusters have helped plug skills and service gaps in these hospitals, there remains a need to keep reviewing the role and performance of district hospitals within the health system.

13.5 Contextual and External Threats

Three external and contextual factors act as potential threats to both human health and the functioning of the health system. While these issues lie outside the health sector, the MoH has previously demonstrated its ability to catalyse actions by other agencies to address health issues (e.g. efforts to improve urban sanitation and reduce environmental health hazards, as described in Chapter 7). The challenge is to adapt and apply this former experience to address each of these current and future threats.

The first threat is a set of environmental health hazards that includes particulate matter, chemical pollutants and microplastics, which pose direct threats to health. In addition, global warming, which involves rising sea levels, flooding, extreme weather events and disruptive weather patterns, will produce direct and indirect threats to health that may include declining food security, forced migration and conflict. While these threats cannot be addressed by the health sector alone, health systems will need to mitigate the effects of global warming and ecological degradation and play a role in moving society away from its dependence on fossil fuel and unsustainable patterns of consumption. There are now a growing number of initiatives and programmes aimed at greening the health sector in various countries across the world, including the WHO green hospitals initiative (Global Green and Healthy Hospitals, n.d.).

The second threat concerns the growing prevalence of diseases caused by the unhealthy consumption of alcohol, tobacco and so-called ‘junk’ food. The growing prevalence of these diseases have been termed industrial epidemics because of their association with various commercial industries. In 2016, non-communicable diseases (NCD) accounted for 74% of all deaths globally (World Health Organization, 2018), while NCD-related morbidities increased by 80% between 1990 and 2013 (Ministry of Health Malaysia & Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, 2016). Evidence points to the need to change the environments in which people live to tackle these diseases, rather than to rely on individual behaviour change. This will require taking public health approaches to regulating the food and retail sector, as well as other social and economic drivers of unhealthy behaviours.

Furthermore, as medical technology advances inexorably and as populations grow older and more morbid, healthcare needs and demands will place ever greater pressure on health systems. While new forms of affordable care and technology may help meet this challenge of growing need and demand, health systems need to prevent disease in order to ‘compress’ the period during which people are living with chronic diseases.

The third threat concerns the continued existence of pockets of intractable poverty and a growing number of people who live unsettled, migratory and marginalised lives. This includes high levels of stunting and maternal anaemia in the urban poor, existing side by side with child obesity (United Nations Children’s Fund, 2018), as well as a large number of undocumented migrants who lack safe access to essential healthcare. Not only does this harm the moral wellbeing of society, it creates vulnerabilities in the population and the health system as a whole in terms of emerging diseases (e.g. HIV, dengue, Nipah virus, SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome)) and re-emerging diseases (e.g. TB, polio, measles, malaria).

13.6 The Applicability of the WHO Building Blocks Framework

Notwithstanding their loosely bound nature and the influence of contextual factors, health systems are also discrete and organised entities in their own right. The WHO framework provides a useful starting point for the analysis of a health system by identifying the key components of the system and suggesting desirable outcomes. However, the experience of applying the WHO framework to a historical analysis of the Malaysian health system has led to several observations about its utility.

First, as others have suggested, the framework can be better organised to describe some of the key relationships between the different building blocks. We propose a framework (Figure 13.2) that identifies ‘governance and leadership’ and ‘financing’ as foundational building blocks. In fact, governance and leadership not only determine the overall structural design and institutional framework (laws, regulations and policies) of a health system but also influences the second foundational building block (health financing), which in turn sets the priorities and determines how the health system is resourced and how the costs and benefits of the health system are distributed across society. ‘Governance and leadership’ and ‘financing’ are also fundamental to determining the social, cultural and political characteristics of a health system, as highlighted in Chapter 1.

The next three building blocks can be depicted as operational building blocks: people (the health workforce), intelligence (the health information system) and products (medicines, vaccines and technologies). These three blocks can also be seen as providing the inputs for the final building block (service delivery), which is therefore also best understood as a cross-cutting building block. This representation of the WHO framework is shown in Figure 13.2.

Figure 13.2 Proposed revised layout of the WHO building blocks depicted in Figure 13.1.

Second, while this description of the WHO framework suggests a linear set of relationships between different building blocks that are logically arranged to deliver services in an organised and planned manner, in reality, health systems are complex and unpredictable, and the different building blocks often interact with each other in a non-linear and unpredictable manner. For example, two operational building blocks (health workforce and health information) play critical roles in enabling good governance and leadership. This is illustrated, for example, by how leadership capacity was developed in the Malaysian system (Chapter 12) and how leadership played crucial roles in influencing the development of environmental health services (Chapter 7) or the delivery of primary care services (Chapter 4). Similarly, the ethos, values and nature of ‘service delivery’ can influence the way in which the other building blocks operate or function (Chapter 5 provides an illustrative example of these interactions).

Third, the interaction between the health system and its wider context includes separate interactions between the wider context and the individual building blocks of the health system. For example, Chapter 11 provides illustrative examples of how the ‘medicines, vaccines and technology’ building block is strongly influenced by national and global intellectual property rights regimes. Chapter 8 illustrates how the ‘health workforce’ building block is influenced by labour migration patterns between public and private sectors, as well as the way in which the education sector is financed and structured. In other countries, supranational migration patterns would be an additional factor. Chapter 12 describes how health sector ‘governance and leadership’ is influenced by national governance and the state of the wider political economy, including the forces of globalisation.

Fourth, any study of the evolution of a health system, including the interactions between its building blocks, requires a historical and longitudinal approach that employs both qualitative and quantitative data. While cross-sectional analyses of health systems may provide a useful snapshot of how they are organised and how well they perform, it is important to be able to tell the story of how health systems have evolved and developed over time to be able to fully understand them.

Finally, while the WHO framework notes the need to assess health systems performance in terms of a set of intermediate goals (access, coverage, quality, safety) and outcome goals (health status, responsiveness, financial risk protection, improved efficiency), it does not consider some of the other purposes of a health system. These include its contribution to the wider economy, its importance in shaping and reflecting socio-cultural norms and values, and its role in mitigating social inequality. It is important therefore to ensure that the WHO health systems framework is used as an evaluative framework in combination with other frameworks (Chapter 1).

13.7 Looking Beyond the Health System and the Building Blocks Framework

As noted in Chapter 1, the WHO building blocks framework does not cover all aspects of the performance of a health system. These include the economic, social and cultural functions and effects of the health system.

It is surprising that the economic function and effects of the health system are not highlighted in the WHO framework, given that this aspect of a health system is well recognised as important. For example, we can assume that healthy growth and nutrition in early childhood will contribute to broader socio-economic development, and there is evidence that health services provided free to the poor contribute substantially to poverty reduction (Reference Hammer, Nabi, Cercone, van de Walle and NeadHammer et al., 1995).

Analysis of the Malaysian health system opens windows to several other issues that are not usually covered in the discussion of health systems. For example, the health system may be expected to contribute to the country’s economy by earning foreign income. For example, in Malaysia, as in many other developing economies, the fledgling medical tourism industry and the domestic pharmaceutical industry are viewed as opportunities to grow the country’s exports. Health systems are also important generators of employment in society. In addition, they create jobs in areas that may otherwise be economically marginalised. This function is rarely considered by health systems planners, who may be more concerned with issues of health systems productivity and the desire to minimise human resource costs.

As countries progress along the developmental scale, the boundaries blur between health issues and issues typically assigned to the realm of social protection. This realm includes activities that make large contributions to health, such as care of the elderly, the provision of social and physical activities, and the integration of people with special needs into mainstream society. However, in Malaysia, as in many middle-income countries, social services are less developed than health services. Unless adequate attention and funding is focused on such services, there is a risk that the health system will end up having to fill the gaps.

The social and cultural aspects of a health system are also often neglected in health systems research and analysis even though they are important purveyors of social, cultural and moral norms and values. For example, the early decades of health systems development in Malaysia reflected a social commitment towards equitable development and uplifting the rural poor. It also stressed the importance of social equity and solidarity by explicitly seeking to reduce disparities in health. The more recent growth of corporatisation and market forces in healthcare delivery could pose implicit challenges to the earlier norms and values, but they are seldom the topic of discussion and debate.

By and large, the health system has also been developed as a secular institution that has worked across racial and religious differences, and it may therefore be seen as contributing to social tolerance and harmony. It also acts as a platform upon which gender norms are reflected and shaped. Further, the manner in which it interacts with traditional medicines and health practices will influence the way traditional cultures are viewed and respected. Equally, the modernisation and commercialisation of the health system will produce new cultural norms.

13.8 Key Messages: Summary of Generic Issues

13.8.1 Generic Lessons Derived from the Historic Evolution of Malaysia’s Health System

The provision of health services to the poor free of charge is an important element in alleviating poverty and enhancing productivity.

People in rural areas can be reached with targeted, effective and low-cost basic health services with improved health outcomes.

Effective and efficient environmental health services are an important corollary to PHC.

The co-ordinated development of the various components of the health system depicted by the WHO building blocks creates strong synergy.

Specific attention to management training and leadership development is key to the ability of the health system to implement initiatives effectively, using information from a variety of sources and responding to new challenges.

13.8.2 Generic Issues Arising from Current Challenges

Rising affluence and urbanisation, associated with the public–private divide in healthcare, could lead to higher THE not associated with improved health outcomes.

Health system managers need competence in using a wide range of governance mechanisms to address such issues.

The major current health challenges have their roots outside the health system. The health system needs to develop innovative approaches to provide acceptable leadership in a multi-sectoral context.

14.1 Lessons from the Case Study Approach

Thus far, we have utilised a problem-based approach in applying systems thinking to health systems. We have surveyed the historical development of the Malaysian health system for adaptive behaviours, unintended consequences, tipping points for change and other systems lessons and presented in-depth systems understandings of problems or interventions in 11 case studies co-developed with health experts (HEs). In addition to providing insights for health systems, described in Chapter 13, this exercise draws out lessons for the application of systems thinking to health system strengthening.

Challenges to developing and applying system insights in health system improvement and elsewhere have been discussed extensively (Reference Trochim, Cabrera, Milstein, Gallagher and LeischowTrochim et al., 2006; Reference Plsek and GreenhalghPlsek & Greenhalgh, 2001; Reference Basile and CaputoBasile & Caputo, 2017). In the process of researching and co-developing the materials for this volume, several obstacles stood out. First, in both interviews and surveys of written documents, we often encountered a plethora of facts with no organising hypothesis. That is, the development of the health system was often described simply as a series of events without critical reflection on how these events were connected and what the key enablers or alternative development possibilities were. While such event descriptions are an important source of data for mapping out the system of interest, this level of synthesis is insufficient for drawing out meaningful lessons.

Where an organising hypothesis was present, there was still a tendency toward simple narratives and universal solutions that frequently obscured complex interactions. For example, health system interventions were often presented as self-contained activities implemented by visionary leaders; much probing was necessary to uncover the contextual factors that allowed a change to occur, that shaped the form of the intervention and that mediated the intervention pathway. Finally, restricted views of the problem space, and of the health system itself, limited the ability to recognise causal pathways — a common reason for the health system shortcomings described in the case studies.

Overcoming these obstacles to understanding complexity is challenging and time-consuming; acting on these insights adds further challenges because co-operation from multiple actors is typically necessary. Thus without tools and incentives to support efforts to pursue systemic understandings, health system actors are likely to base their understanding and decision-making on simplistic mental models.

This is not to say, however, that health system actors are unaware of the complexity of health issues and health systems. Indeed, in the co-production of the case studies, the HEs readily recognised the system effects suggested to them, observed these effects themselves, or had already utilised system principles in making operational decisions. Nonetheless, systemic insights rarely emerged at the outset of the case study collaborations. Instead, the linear cause-and-effect analysis was typically prevalent in initial explorations of health system problems and interventions. While the HEs had, or could readily reach, systemic insights when asked about the broader context of the case studies, they often found it difficult to articulate these insights in understandable ways. Indeed, several proponents had experienced difficulty getting other health system actors to see the issues in the ways they did. This difficulty in communicating systems understandings hinders learning by making it difficult to blend the mental models of the broad range of stakeholders.

Narratives are powerful communication tools, with stories and case studies often being more persuasive than more ‘robust’ forms of evidence in persuading policymakers (Reference Sallis, Bull, Burdett, Frank, Griffiths and Giles-CortiSallis et al., 2016). However, narratives are used for more than communication; the construction of narratives is a sense-making process in which we build understanding. Indeed, we need narratives to make sense of evidence even as we use evidence to construct more accurate narratives (Reference SchlauferSchlaufer, 2018; Reference Rickinson, Walsh, de Bruin and HallRickinson et al., 2019). And, because narratives can be rich and multi-layered and hold competing ideas in tension, they are a useful tool for addressing complexity. However, because they are easier to develop and propagate, many narratives are relatively simple. This is good to the extent that the understandings they communicate are useful. However, for many complex problems in health systems, simple narratives are unable to capture important features of the problem, leading to poor understanding and decision-making. The case studies in this volume are experiments in creating experience-based systemic narratives that better capture the key features of health system complexity and make the related insights more accessible to a broad audience.

It is not possible to prove that a given systemic narrative is accurate; any such ‘proof’ rests on a priori assumptions about what is and is not useful for understanding and decision-making. Nonetheless, we observe that the process of co-producing the systems diagrams developed in the case studies was useful for organising a wide array of data into narratives that captured important interlinkages and placed key feedback at the centre of the story. The diagrams captured intervention-context systems more holistically, typically extending beyond the initial scope proposed by the HEs. When these narratives were presented to stakeholders for feedback, the diagrams provided frameworks that kept the focus on the core hypotheses. Critically, they worked to hold the multi-faceted stories together. In several contentious case studies, the cause-effect pathways portrayed in the systems diagrams helped the team identify points of disagreement and facilitated discussion of the nature of interlinkages and causal mechanisms. These observations are evidence of the utility of the systemic narratives for generating and communicating understanding.

Co-production was critical to the process of narrative-building in the case studies. It required HEs with knowledge about the historical details of the subject, time and commitment to work with systems thinkers (STs) on the systems thinking approach and develop an understanding of the dynamic interactions, and it also required access to the necessary evidence to support the study. Also important was a willingness on the part of the HEs to follow key causal pathways in working out the proper scope of the system, which in some cases resulted in substantial shifts in focus or topic. A few promising case studies were excluded due to the absence of one or more of these key criteria. As with all methodologies that rely on participatory and co-production approaches, effective utilisation of systems thinking for health systems strengthening will require the capacity for engagement and adequate incentives for the necessary actors to participate.

One goal the case study approach did not achieve on its own was creating a clear picture of health systems structures. The case studies presented selected problems or issues in each of the World Health Organization (WHO) health system building blocks. Each case study illustrated multiple relationships between these building blocks, with linkages central to the narratives shown in Table 14.1 to illustrate the nature of the linkages. However, a systems model for representing a generic health system and the key relationships between its component building blocks was not readily apparent from the compilation of examples. In retrospect, this is unsurprising. Just as each case study required an organising hypothesis to make sense of events and data, so a model of a health system would require an organising hypothesis to synthesise the insights from the case studies. This pointed to a need for an a priori theoretical framework and narrative that would help us organise the practical insights from the case studies. Based on this, we began developing a macro-level health system model to serve as a working hypothesis as the basis for further evaluation, critique and development.

| Linkage | Case study | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Service delivery → financing1 | Dialysis services | The model for the provision of dialysis services provides short-term benefit through mobilising private sector resources. In the longer term, however, the strategy threatens to create a major financing challenge in the face of rising rates of diabetes. |

| Service delivery → health information | Telehealth | Local implementation of telehealth systems was driven by perceived needs and constrained by infrastructure and capacity of the service delivery staff. |

| Human resources → service delivery | REAP-WISE | The team approach for service delivery was constrained by the career development paths of individual team members. |

| Rural drinking water | Large community-engaged workforce enabled the Ministry of Health (MoH) to engage in small-scale drinking water and sanitation solutions that the Public Works Department was not positioned to carry out. | |

| Human resources → leadership and governance | Managed care | General practitioners are insufficiently organised and motivated to successfully advocate for governance action to ensure holistic regulation of managed care organisations (MCOs). |

| Financing → service delivery2 | Dialysis services | Capital financing as a constraint to the expansion of dialysis services in the public sector. |

| Clinical waste management | Capital financing as a constraint to upgrading clinical waste management services to meet environmental standards. | |

| Managed care | Strict caps on reimbursement by certain MCOs leads to general practitioners adopting sub-optimal service delivery practices. | |

| Financing → health information | Clinical waste management | Private sector clinical waste management contractors are paid by the weight of clinical waste, generating cost information to incentivise good practices by hospital administrators. |

| Adoption of case-mix | Adoption of case-mix approach would allow the generation of valuable information on medical cases and hospital performance through financing data. | |

| Health information → leadership and governance | Harm reduction approach | Importance of monitoring and reporting stipulated in international agreements for drawing attention to marginalised groups and precipitating change. |

| Health information → human resources | House officer crisis | Lack of monitoring of local and foreign medical student intakes slowed responsiveness of the health system to the influx of medical graduates seeking house officer positions. |

| Health information → financing | Adoption of case-mix | Adoption of case-mix approach would allow better finance planning by hospital administrators and health ministry staff. |

| Medical products → financing | Hepatitis C drug | The system of intellectual property rights to incentivise the development of medical products also shapes the cost of treatment and the burden on public financing systems. |

| Medical products → leadership and governance | Hepatitis C drug | International trade agreements and intellectual property rights on medical products provide governments with the tools and constraints to negotiate prices and seek alternatives. |

| Leadership and governance → service delivery | REAP-WISE | Leadership is necessary to make changes to and invest in the healthcare ecosystem to adopt an integrated care approach in primary clinics. |

| Harm reduction approach | Role of health system actors in engaging different government ministries and non-government stakeholders to generate support and co-ordination for harm reduction approach. | |

| Rural drinking water and sanitation | The MoH took on the responsibility of addressing rural drinking water and sanitation, areas traditionally outside its purview. Leadership was necessary to overcome internal and external resistance to the shift in the scope of service delivery responsibilities. | |

| Leadership and governance → financing | Managed care | Gaps in the jurisdiction have left MCOs largely unregulated by the government. |

| Leadership and governance → health information | House officer crisis | Despite the experience of the house officer crisis, there remains no mechanism for tracking local and foreign medical student intakes. The cross-ministry nature of this problem may complicate solutions. |

| Clinical waste management | Government actors recognised the importance of a hospital waste information system to ensure accountability of private sector service providers and hospital management. | |

| Telehealth | High-level health system leadership was necessary for the extensive implementation of telehealth. The lack of technical expertise at that level created conditions that gave rise to interoperability problems. | |

| Leadership and governance → medical products | Regulation of traditional medicines | The development of a regulatory framework for traditional medicines has shaped their manufacture and sale. |

14.2 Building a Macro-Level Model

In constructing a macro-level model of a health system, we re-visited what it should accomplish. We thought that a useful macro-level systems model of a health system should: (1) improve on existing ways of thinking about the health system and its component building blocks by (2) focusing on the influence pathways that form high-level feedback loops to (3) identify the proper boundaries of the health system. We assumed that the health system building blocks were a reasonable approximation of the scope of the health system and asked what key feedback loops shape each building block. To identify high-level feedback loops, we considered whether the various health system building blocks were subject to different influences and could be categorised accordingly. In this process, we noted that health systems are often described as open systems subject to exogenous forces (Reference GrayGray, 2017) and that many of the feedback pathways ‘travel’ outside the health system. A larger view that includes populations and societies opens up new avenues for advancing health (Reference FrenkFrenk, 2010). Thus we drew on the Cultural Adaptation Template (CAT) developed by Reference Newell, Dyball and NewellDyball and Newell (2015) as the framework for developing a health systems in society model that would encompass these feedbacks and ‘exogenous forces’.

The CAT contains four major sub-systems (Table 14.2): societal institutions, cultural paradigms, human health and wellbeing, and the environment. In our macro-level model, the health system is the key societal institution of interest. Cultural paradigms are the worldviews, paradigms and beliefs held by society. Cultural paradigms, which reflect our understandings of the way the world is and how it ought to be, inform the ways we organise and operate our societal institutions. Human health and wellbeing encompass physiological and psychological health and the holistic meeting of needs critical to human flourishing. The health system contributes to this through the provision of healthcare, while shortcomings in the state of human health and wellbeing place demands on the health system. We have expanded the ‘ecosystem’ contained in the original cultural adaptation template to ‘environment’. The former was limited to the natural and built bio-physical environments; here, we include social environments to more fully represent how the state of the environment shapes the state of human health and wellbeing via the social determinants of health. In doing so, we distinguish between societal institutions and the social environments they create, while recognising that the two are not always neatly parsed.

| Sub-system | Examples |

|---|---|

| Societal institutions | The health system, political lobbyists, legislation on workplace practices, international trade, patent systems, civil society groups |

| Cultural paradigms | Belief in universal healthcare, preference for private over public service providers, openness to immigration, level of trust in government |

| Human health and wellbeing | Prevalence of obesity, suicide rates, incidence of malaria, sense of security, job satisfaction, level of anxiety |

| Environment | Intensity of the urban heat island, air quality, access to healthy diets, amount of green space, level of societal acceptance or hostility |

Model construction began with identifying the relationships between the six health system building blocks and the feedback process that shapes them. An influence diagram format was chosen for its ability to represent broad, high-level concepts. We observed a natural division of the health system based on key drivers. The patient-facing portion of the health system, which we term the ‘provider sub-system’, is directly subject to and shaped by public health needs and demands. The second portion of the health system, which we call the ‘enabler sub-system’, plays a supporting and administrative role and is typically less visible to the public.

In considering the operation of the health system, the six building blocks are not co-equal. Service delivery is the means by which the health system achieves the goal of improving the state of human health and wellbeing; meanwhile, leadership and governance determines how the remaining health system building blocks operate to achieve good service delivery. We thus equate service delivery with the provider sub-system and leadership and governance with the enabler sub-system. The human resources and medical products and technology building blocks belong to the patient-facing portion of the provider sub-system whereas the financing and health information building blocks are less visible and thus placed in the enabler sub-system. ‘Programmes and strategies’ and ‘infrastructure’ have been added to the provider sub-system as key components of service delivery not covered by human resources or medical products and technology based on building block indicators proposed by the WHO and observations from the corresponding chapters in this publication; similarly, ‘policies’ and ‘capacity for decision-making’ have been added to the enabler sub-system (World Health Organization, 2010).

In mapping out important feedback loops shaping the health system building blocks, we propose five types of feedback loops that shape the health system and health outcomes (Figure 14.1). Each of these feedback loop types can be adaptive (i.e. leading to better practices and outcomes) or maladaptive (often due to incorrect understandings of causal relationships or actions that make sense locally but have negative consequences at a higher system level). Adaptive feedback is more likely when actors are aware of the full scope of the system, have good data, work across boundaries and seek global rather than local optimisation.

Type I feedback loops occur due to ‘natural’ interlinkages within a health system building block or between multiple health system building blocks. For example, the purchase of expensive diagnostic medical equipment (medical products and technology) tends to lead to high use of the equipment to justify its purchase (service delivery); apparent demand for that diagnostic service encourages further investment in similar equipment. Some Type I feedback loops are well recognised while others are hidden in the fabric of the health system.

Type II feedback loops stem from direct public demands on health systems resulting from human health and wellbeing (i) and the response of health systems to meet these demands (ii). Public demands are typically directed at the visible provider sub-system. Due to political (for the public health system) and profit (for the private health system) pressures, shortcomings in the provider sub-system are often quickly identified and readily addressed where feasible, making Type II feedback loops relatively responsive.

Type III feedback loops are learning loops within the health system and are often linked to demands generated by Type II feedback loops. Improvements to service delivery frequently require support from the enabler sub-system (iii), while long-term demands and experiences from the provider sub-system shape leadership and governance of the health system (iv). The efficacy of Type III feedback loops often depends on the quality and flow of health information (Reference Scott, Dunscombe, Evans, Mukherjee and WyattScott et al., 2018) and whether rules, structures and incentives align to support or obstruct adaptive learning (Committee on Quality of Health Care in America and Institute of Medicine, 2001; Reference Carroll and EdmondsonCarroll & Edmondson, 2002; Reference EdmondsonEdmondson, 2004).

Type IV feedback loops are intertwined with social determinants of health. Health systems have been primarily organised as healthcare systems delivering services to individuals. Therefore, with a few notable exceptions, the structures, capacity and resource allocation in health systems are not designed to address social and physical environments (v), which in turn play a large part in human health and wellbeing (vi) (Reference Friedman and BanegasFriedman & Banegas, 2018; Reference Solomon and KanterSolomon & Kanter, 2018). Despite the rapid rise of non-communicable diseases (NCDs), effective, large-scale solutions for health promotion and preventative care remain elusive (Reference Baugh Littlejohns, Baum, Lawless and FreemanBaugh Littlejohns et al., 2018). To engage in Type IV feedback loops effectively, health systems will need to recruit and develop new types of expertise and learn to engage issues and stakeholders that have historically been outside its purview.

Type V feedback loops include cultural paradigms, being related to societal learning (vii) and decision-making (viii) processes. These often involve drivers that have been regarded as exogenous to health systems, such as education levels and national budgets. Societal learning shapes crucial beliefs, such as who should pay for healthcare, whether it should be delivered by public or private practice, the level of education required of the health workforce, etc. This learning comes not only from societal perceptions of the state of human health and wellbeing and experiences of the health system; rather, lessons are interpreted and filtered through value systems and a priori beliefs and are in dialogue with other societal narratives. Health systems will never have full control over Type V feedback loops (indeed, health system actors often have less control even over feedback loops within the health system than we would like to think). Nonetheless, health system actors have not only the right but the responsibility to engage with Type V feedback loops — a task that is severely underexplored in the literature and in practice.

This macro-level model highlights the importance of thinking about the larger societal context in which health systems exist. Much of the focus in health systems strengthening has been in improving processes within the health system (i.e. Types I, II and III feedback loops), with a lack of priority placed on intersectoral co-operation (Reference Munir and WormMunir & Worm, 2016). Expanding the view of health systems strengthening, however, raises the question of what else health systems should be doing, who else they need to engage and how they need to be structured and strengthened to do so.

There are limitations in the health systems in society model. The first is related to categorisation and depiction of the variables and their relationships. For example, the health information building block is critical to health system learning processes, and we have postulated that the leadership and governance building block should influence societal learning processes; however, these relationships are not easily represented within an influence diagram. Also, certain variable boundaries are blurry, as noted previously regarding the division between societal institutions and social environments. However, we believe that these limitations do not substantially detract from the insights that can be derived from the analysis of the feedback loops.

Another set of limitations relates to the ways in which this macro-level model can be used. As a conceptual model, it is useful for visualising relationships to formulate broad hypotheses about leverage points for strengthening the health system. It can also be a reference point when constructing more detailed systems diagrams around a particular problem, as a check on whether all the appropriate variables have been considered. It does not, however, provide predictive power. More detailed relationships that can support causal loop diagrams and stock-and-flow models are needed to develop trends and scenarios that have utility for prospective analysis.

Finally, the model remains a hypothesis in need of testing and improvement. We begin such testing in the following section; the health system community needs to do more work to determine if and to what extent the health systems in society model improves the way we think about the health system and how the model can be further developed to better inform various aspects of health system interactions.

14.3 The Case Studies and the Macro-Level Model

Construction of the model began with developing a high-level narrative to interpret the evidence from the case studies. The insights from interpretation were used in turn to evaluate the utility and limitations of the model. There is, of course, a danger that the macro-level model limits the dataset used to evaluate itself, potentially screening out data inconsistent with the assumptions used to build it. This problem is inherent in any theoretical approach, however. We also recognise that the case studies are not representative of the entirety of the Malaysian health system, and that the selection and analysis of the case studies was influenced by the availability of the participating authors and the understandings that they brought. With these caveats, we will draw some observations here.

To investigate whether the findings in the case studies support the health systems in society systems model, we classified each feedback loop from the case studies according to the five feedback loop types present in the model (Table 14.3). All of the feedback loops were readily categorised into at least one of the five types, although some crossed multiple categories. One such example was the efforts to adjust the health system to compensate for the unexpected influx of house officers, which was driven by both experiences within the health system (Type III) and political and societal pressures (Type V) and which created knock-on effects that affected the training process (Type I). After categorising these feedback loops, we examined the frequency of each type (Table 14.4) to determine if particular portions of the systems model were over- or under-represented and what the implications might be for the model and for how we think about health systems.

A key hypothesis in developing the health systems in society systems model was that societal learning processes are important to understanding a health system. This hypothesis is supported by the case studies, in which 9 of the 11 case studies have a systems diagram containing at least one Type V feedback loop, a higher representation than any of the other types (Table 14.4). In each case, a Type V feedback loop was initially an obstacle to achieving a desired change or the precipitator of a disruption to the health system. The two exceptions (REAP-WISE and telehealth) focused on the role of Type I feedback loops in the implementation of a systemic change. The prominence of the Type V feedback loop in key developments in the Malaysian health system point toward this feedback pathway as a critical component with which health systems need to engage. However, health systems often lack leadership and governance capable of initiating and maintaining effective intersectoral collaboration to disrupt maladaptive Type V feedback loops (Reference Baugh Littlejohns, Baum, Lawless and FreemanBaugh Littlejohns et al., 2018).

Among the case studies in this volume, only one, that is, rural drinking water and sanitation, contains a Type IV feedback loop (Table 14.4). This is despite the widely recognised importance of the social determinants of health, especially in the face of rising NCDs. Several linkages between the health system and the environment are apparent in reviewing the historical development of the Malaysian health. There are a few positive examples, with (1) the Malaysian health system being an international leader in addressing rural water and sanitation issues, (2) current engagement in cross-sector efforts in formulating and implementing a National Environmental Health Action Plan, and (3) innovating in community intervention through KOSPEN (Komuniti Sihat Pembina Negara, or Healthy Community Builds the Nation), though rigorous evaluation of its efficacy and impact is still pending. Other examples that we were unable to cover in the book include tobacco control and promotion of good infant feeding practices. Nonetheless, the development of the Malaysian health system — mirroring health systems worldwide — has been almost entirely geared toward the delivery of clinical services. While the clinical services paradigm of health systems has delivered important advances for health in Malaysia and globally, this alone seems unable to support a health system structure that can deliver effective promotive and preventative care today.

In summary: (1) a survey of the case studies shows examples of all five types of feedback loops hypothesised in the model; (2) examples of the health system addressing the environment and social determinants of health were under-represented in our sample, which seems consistent with the composition of the health workforce and expenditure in the health system; (3) societal learning processes were over-represented and played pivotal roles in our sample. These observations, which need to be confirmed by other health system researchers, suggest that effective use of systems tools for health systems strengthening will need to account for wider societal issues and learning processes in feedback analysis.

14.4 Toward the Use of Systems Thinking in Health Systems