The Institute of International Finance (IIF) plays a crucial role in global financial governance. With a membership of over 450 global financial corporations it regularly brings together the “Who's Who” of international financial powerbrokers. The IIF straddles public policy and private interest representation, taking on an increasingly important private governance role. An analysis of the historical development of the IIF therefore provides important insights into the interaction of states and business through evolving patterns of interest representation as well as into the dynamics of public and private mechanisms of global financial governance.

Despite its prominence in global financial governance, there is scant literature on the IIF.Footnote 1 Much of the financial governance literature sees financial associations like the IIF as representing the interests of their market members to public policymakers in a unidirectional manner.Footnote 2 Newman and Posner (Reference Newman and Posner2016, Reference Newman and Posner2018), on the other hand, note that the emergence of global public policymaking processes functions as a focal point, leading the IIF to gear itself toward these policymaking processes. In other words, there is two-directional interaction between interest groups and public policymaking processes.Footnote 3 However, their contributions do not address how the IIF stands in a similar two-directional interaction with the market. The IIF does not only represent interests emanating from its members but also shapes the market through private governance mechanisms.

This paper develops this point through a study of the evolution of the IIF with the aim to understand why it has developed into this hybrid institution that both lobbies public policymakers and implements private governance mechanisms; and what the implications of this evolution are for global financial governance. The paper draws on a unique set of interviews with global financial policymakers spanning three decades, archive materials, and publicly available policy documents.Footnote 4 These sources are linked to wider changes in the global financial system to address three questions: (i) how has the IIF's structure and mission developed; (ii) how has the IIF's role in global financial governance developed; and (iii) how can we explain these developments? In answering these questions, I put forward two novel arguments as contributions to the literature.

First, I argue that to explain the role of private interest groups, analysis of the two-directional interactions between developments in the market, interest groups, and public policymakers is needed. This contrasts with the traditional unidirectional view of lobbying where developments in the market lead to policy preferences that interest groups represent to policymakers. It extends the strand of literature emphasizing the recursive interaction between interest group preferences and public policymaking processes to the relation between interest groups and markets. Through private governance mechanisms, such as norm and standard setting, interest groups shape markets. The IIF sets standards in the market for sovereign debt with respect to transparency and crisis resolution and thereby contributes to the expansion of this market in terms of scope, as well as successfully constrains creditor behavior in sovereign debt crises.

Secondly, I argue that interest groups take on these private governance roles with the aim to remain the preferred interlocutor of public policymakers vis-à-vis competing interest groups. In doing so, they no longer solely represent their members or respond to functional demands resulting from market developments but pursue organizational self-interest and actively shape the market structure. The rise of competing transnational financial associations led the IIF to develop a standard with respect to sovereign debt crisis resolution, which simultaneously shaped the market and public policymaking. The IIF took on this private governance role with the aim to remain the focal point in the area of sovereign debt crisis resolution, where rival capital market associations played an increasing role. This strategy paid off when the IIF was given the central role in the Greek debt restructuring of 2011/12, allowing it to shape the restructuring package and thereby the risk profile of peripheral Eurozone countries’ debt.

These two arguments have important implications for the study of interest groups and global governance. The traditional approach to private sector lobbying needs to be extended to the way interest groups shape markets through private governance mechanisms, and how that recursively feeds back into interest group advocacy and public policymaking processes. In addition, to better understand the emergence of private patterns of governance and its interaction with public governance mechanisms, we should study interest group competition within the opportunities and constraints emanating from global public policymaking processes.

The following section discusses the literature on interest representation and private governance in global policymaking processes. Section two conducts a first empirical test of the expectations developed in the theoretical section by analyzing the organizational developments of the IIF. The third section presents a case study of the IIF's role in the governance of sovereign debt crisis resolution. The final section concludes by discussing how the evolution of the IIF demonstrates that interest groups should be understood in a recursive interaction with changing market structures and public policymaking processes. In addition, the section concludes that it is the competitive dynamic between interest groups that results in the development of private governance roles. Currently under-researched, the role of interest groups in shaping markets warrants further examination.

Private interests and global governance

The re-emergence of global finance in the 1970s and ’80s led to a burgeoning literature on policymaking processes leading to emerging patterns of global financial governance.Footnote 5 The following discussion starts with literature on the role of private interest groups in these processes. Subsequently, the literature regarding the emergence of private governance is discussed.

From one-way to two-way street from Lobbyville

Numerous scholars have demonstrated substantial financial sector influence on global public policymaking processes.Footnote 6 Notwithstanding this extensive scholarship, important questions remain with respect to variety over time and context of financial sector influence, as well as with respect to collaboration and competition among financial associations.Footnote 7 A first strand of literature sees financial associations as representing the interests of their members to public policymakers in a unidirectional manner. This literature implicitly follows a functionalist logic assuming that transnational financial associations emerge as a consequence of financial globalization.Footnote 8 When changes in the market structure lead to shifts in members’ interests, the advocacy of associations adjusts. For example, in the 1990s, large banks increasingly relied on internal risk management models in their credit market activities. Reflecting this change in market practice, the IIF started advocating for banks to be allowed to use their internal models in determining risk buffers. This subsequently became one of the main topics in the renegotiation of the first Basel Capital Accord in the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision.Footnote 9 In sum, advocacy stems from market developments and reflects shifting interests of the market members of the financial association.

In contrast, a second strand of literature argues that there is two-way, recursive interaction between private interest representation and public policymaking processes. Shaffer (Reference Shaffer2003) points to “reverse lobbying” where public officials invite private representatives to provide input into public policymaking processes. The public sector might even be closely involved in the establishment of interest groups.Footnote 10 Newman and Posner (Reference Newman and Posner2016, Reference Newman and Posner2018) argue that the emergence of transnational public policymaking processes functions as a focal point for interest groups, leading them to reorganize and (re-)formulate positions in a “second-order effect.” The advocacy role of private interest groups is thus not only dependent on the “supply side” of market interests but also on the “demand side” of public policymaking processes. Moreover, strategic constraints emanating from public policymaking processes shape private sector positions.Footnote 11 To be successful in influencing European-level public actors, for example, interest groups have to adhere to the European Union's broad goal of market integration. Similarly, stringent domestic regulations can lead interest groups to lobby for comparably stringent global regulations to “level the playing field.”Footnote 12 In sum, this strand of literature emphasizes that the advocacy role of interest groups is co-determined by public policymaking processes.

The focus on lobbying of these two strands of literature underestimates the equally important role of interest groups in developing the market and setting norms for market participants, however. Through private governance, a second recursive relation emerges between the market structure and interest groups.

From lobby to private governance

A growing body of literature addresses private mechanisms of governance at the global level.Footnote 13 This subsection first discusses how business associations shape the development of markets through their activities. Secondly, explanations for why business associations take on such role are discussed.

There are two main mechanisms through which governance activities of business associations shape markets. The first is by increasing market transparency, for example, through (standardized) data collection and dissemination. This reduces transaction costs and contributes to market expansion.Footnote 14 By determining the coverage of data collection, business associations can steer the scope of the market. For example, providing economic data and analysis on new countries can facilitate the inclusion of these countries in the financial markets’ realm. The second mechanism works through constraints on the behavior of market actors, for example, by establishing codes of conduct or by disseminating “best practices.”Footnote 15 Actors that do not adhere to “best practices” or other forms of private governance might be (informally) excluded from the market.Footnote 16 This private norms-setting can also be conducive to overcome collective action problems, which hamper market development.

A first set of explanations for why business associations take up these private governance role sees it as a functionalist response to financial globalization and the increasing complexity of markets.Footnote 17 These market developments make it harder for public policymakers to design and enforce effective regulations, leading them to delegate to the private sector. Business associations are willing to take up this role to reduce the rising transaction costs that come with the increasing complexity.Footnote 18

A second set of explanations focusses on the “shadow of public intervention.” Public policymakers demand the development of governance patterns from the private sector under the threat of public intervention in the market. Oftentimes, this means public policymakers stay involved in the private negotiations as observers, and give their blessing to the resulting private governance mechanisms.Footnote 19 At other times, private governance mechanisms are developed by the private sector to pre-empt (potentially more burdensome) public governance. For example, Helleiner (Reference Helleiner, Mattli and Woods2009) argues that the IIF set up a code of conduct for sovereign debt restructuring as a response to the threat of an International Monetary Fund (IMF) statutory public mechanism.Footnote 20

A third set of explanations points to organizational self-interest in the context of competitive interaction between business associations.Footnote 21 Fragmentation in the structure of interest representation and the resulting competition between interest groups lessens the power they are able to exert over policymaking processes.Footnote 22 Taking up private governance roles counters this diminishing influence. Büthe (Reference Büthe2010a) provides a number of conditions under which private governance can successfully be established in the face of rival associations. First of all, the organizational structure of an interest group should enable it to follow its self-interest (e.g., by having staff capacity), even if it is not of direct benefit to its members. Secondly, building expertise in private governance enables an association to remain pre-eminent as the first mover. Thirdly, the institutional context can enable certain interest groups to establish private governance mechanisms over others. For example, transnationalization of public policymaking has a second order effect on the competition between interest groups that benefits those associations that are similarly transnational.Footnote 23

In sum, different expectations emerge in the literature with respect to the evolution of the IIF's advocacy and private governance role. The functionalist explanation would expect the IIF to take up a governance role in response to the growth and increasing complexity of the sovereign debt market. The shadow of public intervention explanation would expect the IIF to develop private governance mechanisms in response to the threat of public mechanisms. The interest group competition explanation would expect the IIF to take up governance roles in response to other associations encroaching on its turf. The establishment of private governance mechanisms creates a recursive relation between association and market structure: the association represents its members’ interests, but also feeds back into the market with private governance mechanisms constraining members’ behavior. These expectations will be investigated by analyzing the organizational development of the IIF (next section two) and its role in the governance of sovereign debt crisis resolution (section three).

Structure and mission

This section analyzes the origins, membership, mission, and activities of the IIF in relation to public policymaking processes and market developments. This provides a first test of the nature of these relations as one-way or recursive.

Origin

The idea for establishing the IIF was conceived at a conference of high-level public and private policymakers sponsored by the American think tank the National Planning Association (May 1982, Ditchley Park, United Kingdom). The increasing involvement of private banks in sovereign lending to emerging markets since the 1970s had led to a patchy picture of the exposure and economic developments in these markets. The IIF was intended to provide a forum for exchange of information, and thereby increase transparency in the market. This would contribute to a better assessment of the risks of banks loans to emerging markets, and thereby benefit further market growth. Although a role as negotiating forum between debtor countries and the private sector in case of sovereign debt crisis was discussed, in the end, the IIF explicitly rejected this role out of concern for US antitrust law.Footnote 24 The IIF emphasized that it did not intend to present a united front of bankers to borrowing countries. The IIF was formally established in January 1983 and took office in Washington, DC.Footnote 25 This location was chosen in light of its close cooperation with the IMF and the World Bank and to underscore its independence from Wall Street banks.Footnote 26

Public officials at the Ditchley Park meeting had welcomed the idea of a private sector association. Jacques De Larosière, managing director of the IMF, in particular encouraged the idea. The IMF's Executive Board was extensively briefed on the IIF's establishment, pointing out that it could function as “a focal point for dialogue between the international banking community and multilateral institutions, central banks, and supervisory authorities in the developed countries.”Footnote 27 The IMF, BIS, and OECD granted the IIF access to their hitherto confidential reports, providing an important impetus to the new association. In other words, from its origin, the IIF was not just a reflection of market interests but just as much a reflection of the demand by public policymakers for an interlocutor.

Membership

At its establishment, membership was limited to banks with (impending) international exposure. Thirty-eight banks from Belgium, Brazil, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States became founding members in January 1983.Footnote 28 Against the backdrop of the Latin American debt crisis, membership rapidly expanded in the first year to almost 190 banks.Footnote 29 Subsequently, membership numbers decreased steadily until the midnineties. Syndicated bank lending to emerging markets effectively stopped, so many smaller banks were no longer internationally active and cancelled their membership. In addition, mergers and acquisitions among the membership reduced its number.

The decline was mitigated by rising membership of nonbanks, such as investment managers. These had become increasingly involved in bond market financing of emerging markets, filling the gap left by the reduction of bank lending. The IIF also initiated new advocacy work as a membership recruitment tool, opening up to a widening range of financial institutions. This started with work on the market risk amendment to the Basel Capital Accord, which was particularly relevant for investment banks.Footnote 30 At a later stage, the IIF's importance as a financial sector advocate at the global level resulted in insurance companies joining the IFF rather than forming a new transnational financial association when policymaking in the insurance area moved to the global level. The IIF duly expanded its work in this policy area.Footnote 31

IIF membership also expanded geographically. From the early 1990s, banks from emerging markets increasingly found common ground with the traditional membership and joined.Footnote 32 Following the 1997/1998 East Asian crisis, a second wave of financial institutions from emerging markets joined, wanting to be heard in global-level policymaking.Footnote 33 Today, full membership is open to firms who are internationally active in banking, securities, and insurance. Associate membership and special affiliations are open to another set of institutions active in the global financial system, like accountants, multilateral development banks, export insurers, and stock exchanges.Footnote 34 Membership stands at more than 450 institutions from over seventy countries, with about half of the membership from emerging markets.Footnote 35

Membership dues are determined by type and size of member institutions. In 1987, the IIF's budget stood at US$9.3 million (in 2018 dollars) rising to $34.5 million in 2018. Staff increased over this period from about forty to about eighty. General meetings are scheduled to coincide with the IMF and World Bank Spring and Annual Meetings, to facilitate exchange with these institutions.Footnote 36 In addition, the IIF opened representative offices in, amongst others, Beijing (2010) and Brussels (2017) to strengthen ties to regional members and engage regulators in Asia and Europe.

The development of its membership was aptly summarized in the IIF's 1994 Annual Report: “Some observers still view the Institute as a G-10 commercial bankers’ club addressing the international debt problem of the 1980s. This view is incorrect. The securitization and globalization of financial markets have led the Institute to adapt both the structure and composition of its membership.”Footnote 37 The IIF not only changed its membership, though, but also its activities.

Mission and activities

The original mandate of the IIF was “to promote a better understanding of international lending transactions generally; to collect, analyze and disseminate information regarding the economic and financial position of particular countries which are substantial borrowers in the international markets (…); and to engage in other appropriate activities to facilitate, and preserve the integrity of international lending transactions.”Footnote 38 The latter clause was soon interpreted as to include advocacy work, which forms a first pillar of the IIF's activities. From 1985 on, the IIF sends a bi-annual letter to the members of the IMF's main governing body to inform them of its positions regarding the agenda of the day.Footnote 39 In 1986, the incoming Managing Director Horst Schulmann aimed “to make the IIF into an organization that speaks for the international banking industry the way the American Bankers Association speaks for the domestic banking industry.”Footnote 40 Policy advocacy further intensified after Charles Dallara took the reigns as managing director in 1993. This is reflected in the current mission statement: “to support the financial industry in the prudent management of risks; to develop sound industry practices; and to advocate for regulatory, financial and economic policies that are in the broad interests of its members and foster global financial stability and sustainable economic growth.”Footnote 41

The IIF focuses its advocacy work on the global level, with only limited involvement in domestic-level implementation of international regulations.Footnote 42 Policy positions are developed through a self-selecting working group and committee structure broadly representative of the membership.Footnote 43 This works well since “these major banks, Barclays, Citibank, might find they have in fact more in common with each other than with smaller banks of their own country.”Footnote 44 Its advocacy work responds to the emergence of global-level public policymaking processes. For example, the IIF organized its regulatory work in the field of bank capital adequacy standards in such a way as to mirror the Basel Committee structure.Footnote 45 In turn, the Basel Committee, on occasion, asks the IIF to coordinate private sector input when new topics emerge in the policymaking process, and closely collaborates with the IIF in general.Footnote 46

In comparison to other associations, the IIF seeks a pro-active stance to public policymaking processes and frames its policy positions in less technical terms.Footnote 47 It seeks to develop policy positions from the wider perspective of the global financial system, not necessarily narrowly reflecting member interests. As longstanding Managing Director Dallara puts it “we were there as a voice of the private financial community, but we were never a blind advocate for bad practices, weak governance, or weak risk management.”Footnote 48 This is reflected in positions that echo public policy goals, such as international financial stability, and demonstrates how the IIF can follow its self-interest.

The second pillar of the IIF's work is economic analysis and provision of emerging market data to its members. When public availability of economic data increased and members strengthened their analytical capacity, the IIF increasingly focused on smaller countries for which it was more likely that its members had no in-house expertise.Footnote 49 In addition, from the early 1990s on, the “Capital Flows to Emerging Market Economies” report is publicly released and has received significant media attention. Through the provision of data and analysis, the IIF increases market transparency and contributes to expanding the scope of sovereign debt markets to smaller countries.

The IIF has expanded its economic analysis and data provisioning work with standard-setting. Its 1995 report “Improving standards for data release by Emerging Market Economies” indicates economic variables that countries should publish and with what frequency they should do so.Footnote 50 After some years of monitoring compliance, this work fed into the IMF's Special Data Dissemination Standard.Footnote 51 The IIF subsequently shifted focus to Investor Relations, establishing best practices and a “Sovereign Investor Relations Advisory Service” in 2002.Footnote 52 From 2005, it regularly scores countries on their investor relations practices.Footnote 53 The IIF thus increasingly takes on a private governance role with respect to transparency of the debtor side of the market for sovereign debt and aims to shape debtor behavior when it comes to investor relations.

In sum, this section demonstrates that the organizational evolution of the IIF not only follows developments in the market but also responds to developments in public policymaking processes. Its membership expanded as a consequence of changes in the market structure like global integration, but also because the IIF pro-actively developed advocacy work in the area of bank capital adequacy regulation in response to developments at the Basel Committee. Furthermore, the evidence presented demonstrates that the IIF plays an important role in increasing transparency in the market for sovereign debt and has developed a governance role with respect to data dissemination standards. In other words, the IIF contributed to the expansion and shaping of this market (e.g., the inclusion of smaller countries). The following section provides a second empirical test of the recursive relations of the IIF to markets and public policymaking processes through a case study of the governance of sovereign debt crisis resolution.

Governing sovereign debt crises

Since the growth of private sovereign lending stood at the origins of the IIF, the policymaking process on the governance of sovereign debt crisis resolution is a key case to analyze the development of its role. The various governance mechanisms proposed in response to the sovereign debt crisis differ in the extent to which they constrain different sets of private actors.Footnote 54 The private sector prefers market-based governance mechanisms that steer toward voluntary debt restructurings.Footnote 55 This puts less constraints on market actor behavior, and hence limits risks of losses for private creditors. On the other side of the spectrum are proposals for a statutory mechanism (a “bankruptcy court for states”), which would be able to enforce debt restructurings on private creditors.Footnote 56 This case study analyzes the role of the IIF in different episodes of policymaking responding to sovereign debt crises from the 1980s Latin American debt crisis to the Greek restructuring in 2011/12. The increasingly significant private governance role the IIF has taken in this policy area will be explained and its impact on the market discussed.

The Latin American debt crisis: lobbying for public support

In the summer of 1982, Mexico shocked markets by declaring that it could no longer fulfill its debt obligations. Other emerging markets followed, making it apparent that the banks’ capacity to meet losses was insufficient. In the United States, banks’ exposure to the seventeen most indebted emerging markets was well over 100 percent of capital, while for British banks it stood at 85 percent of capital.Footnote 57 Pressured by the IMF and American Treasury Secretary Baker, banks agreed to rollover (part of) their loans in return for official crisis lending and economic reforms in the debtor countries.Footnote 58

The coordination of bankers’ positions in country cases took place in informal creditor committees (so-called London Clubs). The IIF's involvement in this process was limited to coordinating the smaller banks, which were not usually part of this London Club resolution process.Footnote 59 While it proved relatively easy to find consensus in London Clubs immediately after Mexico's announcement, national differences in the handling of the crisis made it more and more difficult to maintain the private sector consensus.Footnote 60 This offered an opportunity for the IIF to establish itself as the advocacy group for the global banking community (as discussed above). The IIF argued that more official lending and economic reforms would suffice to resolve the crisis without (involuntary) restructuring of private debts. This contrasted with several proposals for statutory mechanisms to force a restructuring of the Latin American debts.Footnote 61

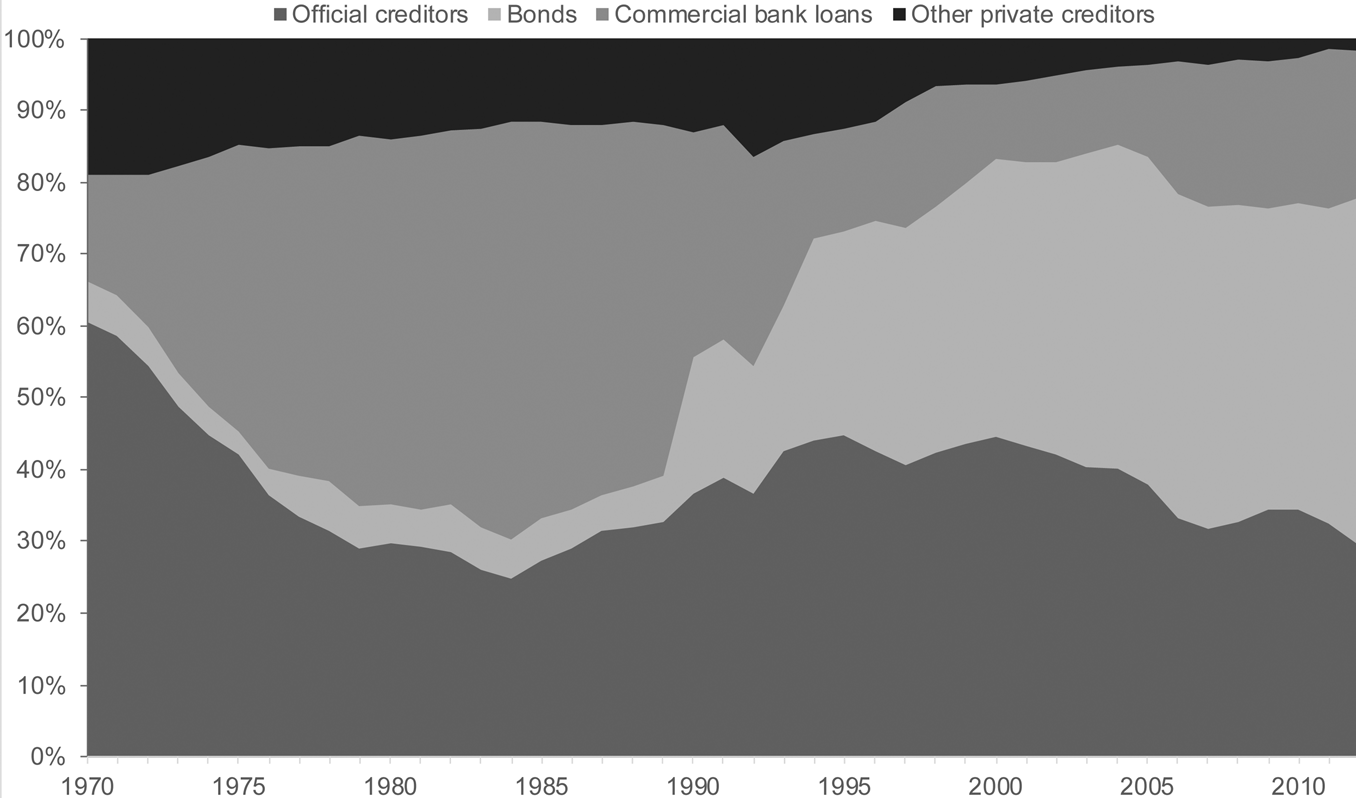

As the crisis dragged on during the 1980s, the new American Treasury Secretary Brady decided to break the stalemate. His 1989 plan offered a securitization of emerging market debts backed by official financing and private debt restructuring. The IIF responded negatively and emphasized that the Brady plan was leading to increasing arrears in emerging markets and potentially eroded market discipline in the international financial system. It advocated for voluntary debt reductions and IMF pressure on debtor countries to maintain interest payments to commercial banks.Footnote 62 Despite the IIF's lobby, the Brady plan went ahead and turned out to have a significant impact on the emerging market debt market (see figure 1 below).

Figure 1. Components outstanding debt upper-middle-income countries

Source: World Bank International Debt Statistics

The securitization of emerging market debt under the Brady plan led to a large increase in bond financing of emerging markets, offering new profit opportunities to banks. These benefits led the IIF to soften its opposition to this ad hoc resolution of the debt crisis.Footnote 63 In other words, the public governance mechanism developed to deal with the Latin American debt crisis led to a change in the market structure for sovereign debts, which subsequently caused a shift in the IIF's position.

The East Asian crisis: grappling with collective action

Despite the proclaimed success of the Brady plan, Mexico found itself in crisis again in 1995. When it proved difficult to coordinate dispersed bondholders into debt rollovers, the increasing sums of official crisis lending necessary to quell the crisis became clear. In response, the Group of 10 (G10, a grouping of public officials of creditor countries) started work on a standard for so-called Collective Action Clauses (CACs), which facilitate bond restructurings.Footnote 64 The IMF started work on a statutory mechanism to enforce debt restructurings through public intervention.Footnote 65 The IIF resisted these initiatives and continued to argue for market-based, voluntary approaches.Footnote 66 It highlighted its work on data dissemination standards and investor relations as the way forward.Footnote 67 In other words, it proposed a private governance pattern that focused on increasing market transparency through constraining debtor states’ behavior.

The 1997/1998 East Asian crisis strengthened the resolve of public officials to develop mechanisms that could limit official crisis lending. In response, the IIF launched its “most ambitious project ever in the regulatory field” in the form of the high-level Steering Committee on Emerging Markets Finance.Footnote 68 Common threads through the advocacy of the Steering Committee were increasing transparency on the part of debtor countries, a case-by-case approach, and opposition to nonvoluntary private sector involvement. The IIF did support the public sector in addressing so-called vulture funds: creditors that bought distressed country debt and aggressively pursued repayment.Footnote 69 This can be interpreted as an attempt to accommodate public sector preferences for orderly restructuring while simultaneously shaping the market by excluding “free riders” amongst private creditors.

The IMF's work on a statutory approach got a high-profile push in 2001 by First Deputy Managing Director Anne Krueger when she proposed the Sovereign Debt Restructuring Mechanism (SDRM).Footnote 70 When Krueger had sounded the idea of the SDRM in the IMF's Capital Markets Consultative Group, private representatives reacted more or less indifferently. They expected the proposal to be too complex to get anywhere. Only the IIF was outspoken in it opposition from the start, diverging from its members.Footnote 71 After the November 2001 launch of the statutory proposal, the IIF was again quick to voice condemnation.Footnote 72 In a private meeting with public officials, Dallara described the SDRM as “a complete abrogation of creditor's rights” and “an obstacle to globalization as evidenced by the support of anti-globalization NGOs like the Jubilee Debt Campaign.”Footnote 73 This divergence between the position of IIF members and the IIF itself illustrates its increasing capacity to pursue an independent course of action, as well as its concern with preserving the globally integrated market structure.

As a demonstration of the shadow of public intervention, which the IMF's proposal cast, the IIF reversed its opposition to the contractual approach of the G10. It took the lead as liaison representing a coalition of interest groups involved in capital market financing of sovereign debts to Randall Quarles, the United States Treasury official chairing the working group that was developing the G10 model for CACs.Footnote 74 Its long-standing expertise vis-à-vis the newer capital market associations likely explains the IIF's ability to take the lead in this process. At the same time, the IIF built a broad private sector coalition of financial associations to oppose the SDRM.

In light of the private sector opposition and hesitations on the part of the United States, public officials of creditor countries increasingly recognized that their support for the SDRM was a leverage instrument to get the private sector to commit to CACs.Footnote 75 The IIF upped the pressure by making clear that its support for CACs was conditional: the IIF-led coalition threatened to withdraw its support for the CACs if discussions on the SDRM continued.Footnote 76 The traditional IIF policy brief in advance of the IMF Spring Meeting was this time accompanied by high-level visits of local banks to public policymakers to drive home the point.Footnote 77

The anticipated effects of the SDRM on the market structure proved to be the final nail in its coffin. Emerging markets feared that the implementation of a statutory approach would increase borrowing costs because the private sector would be more constrained in case of debt crisis. This led them to side with the coalition of financial associations in opposition to the SDRM. Just before the SDRM was coming to a make-or-break decision at the 2003 IMF Spring Meeting, Mexico conducted a widely publicized bond issuance with CACs—as it later admitted “to get rid of the SDRM.”Footnote 78 As intended, the SDRM was shelved that Spring Meeting.

In sum, the IIF has successfully represented its members’ opposition to statutory mechanisms. The anticipated effects on the market for emerging market debt proved to be an important factor in forming a coalition with emerging market officials. Under the shadow of public intervention, the IIF did agree to a public governance mechanism in the form of a G10 model for collective action clauses in international bonds of emerging markets. In the process, other financial associations representing capital market actors had gained relevance in the governance of sovereign debt crisis resolution.

The Principles: taking center stage

The IIF spotted an opportunity to remain the focal point for global public policymakers in the face of increasing competition of other associations when the governor of the Banque de France (Jean-Claude Trichet) proposed to develop a Code of Good Conduct for relations between sovereign debtors and creditors.Footnote 79 This Code aimed to facilitate orderly sovereign debt crisis resolutions through early engagement with creditors, information sharing, comparable treatment among creditors, fair burden sharing, negotiating in good faith, and restoring debt sustainability. With his proposal, Trichet also aimed to restart a constructive dialogue among public and private actors after the confrontational discussions on the SDRM.

The IIF latched on to this idea and contacted Trichet.Footnote 80 The G20 agreed to delegate the development of the Code to a working group led by the Banque de France and the IIF.Footnote 81 The working group included four key emerging markets (Brazil, Mexico, South Korea, and Turkey) and capital market associations. The public sector thus put the IIF in the driver's seat, even more so as the Banque de France subsequently left the working group. The Banque de France reasoned that compliance with a voluntary code was best ensured if it was developed by its subjects alone.

The IIF took this opportunity and relegated the other associations to the backbenches, pointing to its earlier work on sovereign investor relations as the natural precursor to this work.Footnote 82 During the negotiations, the emphasis shifted from a Code of Conduct for debt restructuring to principles for crisis prevention through more debtor transparency and dialogue with creditors.Footnote 83 However, the private governance pattern, which the Code entails, also intends to constrain the behavior of emerging markets creditors. For example, creditors are encouraged to participate in debt rollovers and should engage in good faith restructuring negotiations.Footnote 84

In November 2004, the IIF presented the “Principles for Stable Capital Flows and Fair Debt Restructuring in Emerging Markets.” They were “welcomed” and “supported” the same weekend by the G20.Footnote 85 Reflecting the strive among associations, the Emerging Market Traders Association and Emerging Markets Creditors Association did not support the Principles because they perceived them as insufficiently in line with private sector preferences.Footnote 86 Market participants’ initial response ranged from mildly positive to critical. Many market participants did not seem to think the Principles would be very relevant.Footnote 87 However, this misread the ability of the IIF to follow its organizational self-interest and entrench the central private governance role it had obtained.

The IIF established the Principles Consultative Group (PCG) and a Group of Trustees of the Principles in 2005 to monitor the implementation of the Principles. These groups are used to draw in top-level public and private policymakers. The Trustees are currently co-chaired by Axel Weber (Chairman of UBS AG, former Bundesbank president), Francois Villeroy de Galhau (Governor Banque de France), and Yi Gang (Governor People's Bank of China).Footnote 88 The PCG's annual “Principles Implementation Report” assesses sovereign debtors’ and creditors’ compliance with the Principles and provides case studies of debt restructurings under them. In late 2006, the PCG also established a working group to define a balanced application of the Principles toward investors and creditors.Footnote 89 In individual debt restructurings, “Principles-based” creditor committees have convinced other creditors to join the restructuring, reflecting an effect of the Principles on the behavior of market actors.Footnote 90

Through its continuing focus on the implementation of the Principles, the IIF, in effect, functions as the central (private) governance mechanism in the resolution of sovereign debt crisis, while it co-opts public sector officials in the Group of Trustees. In doing so, it remains the preferred interlocutor of the public sector in the face of increasing competition from other associations. The implementation of the Principles meant the IIF went beyond its members’ interests (as reflected in the indifferent initial response of market actors) and constrains their behavior by setting a standard of collective action. These effects of the Principles were put in sharp relief by the Eurozone crisis.

The Eurozone crisis: IIF in the lead

In the wake of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, several countries in the periphery of the Eurozone struggled with excessive debt burdens. A series of IMF rescue packages in 2010 (Greece and Ireland) and 2011 (Portugal) was followed by an unprecedented debt restructuring in Greece in 2011/12. The Eurozone crisis presented new challenges for public policymakers, as these countries were part of a monetary union and most Eurozone sovereign debt was domestic (and thus did not include the G10 model-CACs). The Principles allowed the IIF to play a crucial role in the European policymaking process on governance mechanisms as well as in the actual restructuring of Greece.

At the global level policy discussions, some academics and think tanks again put forward more interventionist statutory proposals.Footnote 91 These proposals were mostly ignored, however. European governments worried that opening a discussion on statutory mechanisms would lead to contagion, while the IMF noted that there was still a lack of support amongst its membership as the United States continued to oppose. Since these proposals gained limited traction in the global policymaking process, the IIF did not see the need to set up a high-level lobby campaign as it did in the wake of the East Asian crisis.

The situation was different at the EU level, however. Germany proposed a European sovereign debt mechanism with private sector involvement (although without being clear how this would be enforced) in October 2010. Although the IIF usually focuses on global policymaking processes, this announcement led them to intensify engagement with the European process. The German proposals set off intense negotiations in the European Union, during which the IIF lobbied the European institutions and Eurozone ministries of finance to ensure the European plans would be consistent with the voluntary, market-based approach of the Principles.Footnote 92 The IIF emphasized that restructuring should only be a last resort.Footnote 93 France was receptive to the IIF's position since its banks were heavily exposed to the crisis countries. Additionally, the possibility of a nonvoluntary restructuring had led to a drastic reassessment of risks of sovereign lending to peripheral Eurozone countries, which deepened the crisis. This ensured that a statutory mechanism was quickly taken off the table, despite initial German support.

In a December 2010 meeting, the chairs of the European Council (Van Rompuy) and the European Commission (Barosso) reassured the IIF that the EU's framework would be consistent with the Principles and was based on a voluntary case-by-case approach.Footnote 94 This was confirmed by the European Council in March 2011. The EU compromise consisted of two planks with respect to sovereign debt restructuring (in the context of setting up the European Stability Mechanism, the EU's own rescue fund). Bonds emitted by Euro Area member states would include CACs based on the G10 model clauses. This meant that this global governance mechanism was extended to domestically issued bonds, at least in the Eurozone. The other plank was the possibility of debt restructurings, based on provisions similar to those in the Principles.Footnote 95 It is telling that the IIF was able to establish such high-level access to the policymaking process compared to other (European) financial associations. Its role as steward of the Principles certainly played a role here, as it did in the IIF's involvement in the unique debt restructuring case of Greece.

Despite the rescue packages, the situation in Greece deteriorated to the extent that its sovereign debt was unsustainable. European public policymakers invited the IIF to perform what the IIF itself described as an “unprecedented and vital role as a guiding force and honest broker with regard to private sector involvement in support of Greece.”Footnote 96 In other words, taking up a role as private governance mechanism has allowed the IIF to play a central role in subsequent cases of sovereign debt restructurings.Footnote 97 This enabled the IIF to ensure that the Greek crisis did not set unwanted precedents and was in line with the market-based approach to sovereign debt crises.

In its dealings with Greek and European officials, the IIF emphasized that the Principles were the international standard for sovereign debt restructurings. This enabled it to successfully push back on suggestions from, amongst others, the German Chancellor's office and Greece that an involuntary debt restructuring should be attempted.Footnote 98 The October 2011 Eurosummit committed to a voluntary restructuring, in line with the norm espoused by the IIF. The IIF did not only constrain public policymakers with its private governance mechanism, however. It also constrained private creditors into collective action. When faced with private creditors who wanted to make a deal on their own or holdout, the IIF would bring the Principles to bear to ensure wide participation in the deal the creditor committee headed by Dallara had struck.Footnote 99 Its success in doing this is reflected in the high participation rate in the final deal reached in February 2012, which was approved by creditors representing 84 percent of eligible debt.

In sum, this case demonstrates how the IIF evolved into the principal private sector interlocutor for global public policymaking processes during the Latin American debt crisis, advocating increased official crisis financing. However, the shift to capital market financing of emerging markets as a consequence of the Brady plan led to the rise of rival financial associations. In subsequent discussions on the governance of sovereign debt crisis resolution in the wake of the East Asian crisis, the IIF took on a private governance role through the Principles. Self-interest in the context of interassociation competition best explains why the IIF took on this role. The development of the Code only began in earnest after the SDRM had already been shelved, indicating that the shadow of public intervention does not convince as an explanation. The IIF's role in this private governance mechanism also doesn't fit with a functionalist demand from the market, witnessed by the lukewarm reception by its members and the opposition of other financial associations.

The effectiveness of the IIF's self-interested strategy was demonstrated in the Eurozone crisis. The Principles ensured the IIF of a key position in European-level policymaking processes on sovereign debt crisis resolution as well as in actual crisis negotiations. They were key in setting the norm for public policymakers in the Eurozone debt crisis. Importantly for the argument developed in this paper, the Principles also constrained the private creditor side of the market. The norm of collective action in sovereign debt restructurings, which the Principles instilled in the private sector, leads to a reassessment of credit risks of emerging markets and thus affects the market. One could say that the IIF developed over this time from a poacher seeking public bailouts to a gamekeeper forcing private creditor participation in restructurings. The next section will develop the overarching conclusions we can draw from the development of the IIF in relation to changing market structures and public policymaking processes.

Conclusion

This paper aimed to understand the role of the Institute of International Finance in global policymaking processes and governance through a study of its historical development and involvement in the governance of sovereign debt crisis resolution. Three questions were addressed: (i) how has the IIF's structure and mission developed; (ii) how has the IIF's role in global financial governance developed; and (iii) how can we explain these developments?

The analysis demonstrated that the role of private interest groups like the IIF can be explained by analyzing the two-directional interactions between developments in the market, interest groups, and public policymakers. The uniquely influential role of the IIF is as much driven by its powerful membership base as by the “demand side” of global level policymakers who prefer it as an interlocutor. Faced with emerging, global public policymaking processes, the IIF restructured its organization, expanded its membership, and took on private governance roles to remain the key interlocutor. Moreover, a similarly recursive relation exists between market structure and interest group. Through activities aimed at increasing transparency in the market, the IIF contributes to the expansion of the market and shapes its scope. Organizational self-interest and competition with rival associations explain why the IIF developed private governance mechanisms with respect to sovereign debt crisis resolution, which subsequently shaped this market by instilling a norm of collective participation in debt restructurings. The IIF succeeded in remaining the private sector focal point in global financial governance, even though earlier changes in the market structure would have warranted a more prominent role for other associations.

These conclusions have a number of important implications for the literature on global governance and private interest representation. First, it points to the need to reconceptualize interest group dynamics. The traditional unidirectional analysis of lobbying, where developments in the market lead to policy positions that interest groups represent to policymakers, does not suffice to fully understand private interest representation. The recursive relations between interest groups, public policymaking processes, and developments in the market structure should be analyzed. The advocacy of interest groups might be as much driven by developments in public policymaking processes as it is by changes in market structures. More importantly, the evidence presented here suggests such recursive interactions go beyond the interest group—public policymaking process relation. Interest groups shape the market structure through private governance mechanisms as much as they represent market interests. In other words, to fully understand the role of interest groups we need to extend the analysis to private governance mechanisms and their impact on the market.

Second, we need to analyze private governance in relation to public policymaking processes and competition among interest groups. Recently, the literature on private-sector influence on global public policymaking processes has increasingly focused on coalition formation.Footnote 100 However, the analysis presented here points to the importance of analyzing interest group competition, how that leads to patterns of private governance, and how these relate to the opportunities and constraints emanating from global policymaking processes. This is an important extension of recent literature on global governance.

These implications point to a number of avenues for future research. First of all, more research into the IIF as an intermediary between the market and public policymaking is warranted: Is the IIF an effective two-way translator making proposals for both market agents and public policy makers simultaneously? In addition, the framework developed in this paper should be examined and refined in policy areas beyond finance. Another important line of enquiry is the analysis of the effectiveness of the private governance role in terms of shaping markets, what the drivers of more or less effective governance roles are, and how it feeds back into interest group structure and behavior. Finally, the determinants of interassociation competition in relation to developments in the market structure could be further theorized and empirically assessed. Pursuing these lines of inquiry will make important contributions to our understanding of the relations between market structures, interest representation, and public policymaking processes.