Introduction

Irish clinicians are at the precipice of the most significant change in Irish Capacity legislation for over five decades.

The Assisted Decision-Making (Capacity) Act 2015 (‘ADMCA 2015’) was passed into law 4 years ago, but its main provisions have yet to be commenced. The majority of decisions regarding patients who lack capacity are currently made informally although there are two exceptions. The first relates to the involvement of the High Court in decision-making using Wardship procedures based on the Lunacy Regulation (Ireland) Act 1871 and s.9 of the Courts (Supplemental Provisions) Act 1961. The second relates to those involuntary patients who fulfil Section 57(1) of the Mental Health Act 2001. The Lunacy Regulation (Ireland) Act 1871 will be repealed and Wardship jurisdiction abolished for new applicants with full commencement of the ADMCA 2015.

The assessment of capacity is central to the role of the doctor irrespective of their medical speciality but is particularly relevant to the role of psychiatrists, who may be called upon to assist other specialities in complex clinical scenarios. Contemporary Irish research shows that 34.9% of psychiatry inpatients (Curley et al., Reference Curley, Murphy, Plunkett and Kelly2019) and 27.7% of general medical or surgical inpatients lack capacity for treatment decisions (Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Fleming, Curley, Duffy and Kelly2019). There is therefore a need for frontline psychiatrists and other medical specialities to be familiar with current legislation and aware of changes in practice as the legislation evolves.

This editorial seeks to outline the changes in practice arising from evolving law and proposes quick reference algorithms for practice that highlight such changes.

Capacity: current guidance

The Medical Council (2016) stated that ‘A person lacks capacity to make a decision if they are unable to understand, retain, use or weigh up the information needed to make the decision or if they are unable to communicate their decision, even if helped’. Unless there is someone else with the legal authority to make decisions on the patient’s behalf, this guidance advises that the clinician ‘will have to decide what is in the patient’s best interests. In doing so, [the clinician] should consider: which treatment option would give the best clinical benefit to the patient; the patient’s past and present wishes, if they are known; whether the patient is likely to regain capacity to make the decision; the views of other people close to the patient who may be familiar with the patient’s preferences, beliefs and values; and the views of other health professionals involved in the patient’s care’.

The Health Service Executive (HSE) is the country’s national health agency and its Consent Policy (2019) states that while there is a presumption of capacity, capacity to consent should be assessed if there is sufficient reason to question that presumption. Assessment involves evaluating whether ‘the service user understands in broad terms and believes the reasons for the nature of the decision to be made’; whether ‘the service user has sufficient understanding of the principal benefits and risks of an intervention and relevant alternative options after these have been explained to them in a manner and in a language appropriate to their individual level of cognitive functioning’; and whether ‘the service user understands the relevance of the decision, appreciates the advantages and disadvantages in relation to the choices open to them, and is able to retain this knowledge long enough to make a voluntary choice’. This policy, in keeping with the current legal position, states that ‘no other person such as a family member, friend or carer and no organisation can give or refuse consent to a health or social care service on behalf of an adult service user who lacks capacity to consent unless they have specific legal authority to do so’.

Current legal test for capacity

The current legal test for capacity in Ireland is set out in case law (Fitzpatrick v. F.K. (2009)). The test for assessing capacity includes a presumption that an adult patient has capacity, but that presumption can be rebutted. In determining whether a patient lacks capacity to make a decision to refuse medical treatment, whether by reason of permanent cognitive impairment or temporary factors, the test is whether the patient’s cognitive ability has been impaired to the extent that he or she does not sufficiently understand the nature, purpose and effect of the proffered treatment and the consequences of accepting or rejecting the treatment in the context of the choices available at the time the decision is made. In setting out this test, the Court made reference to the three-stage approach to a patient’s decision-making process adopted in Re C. (Adult: refusal of medical treatment) (1994). The latter test includes comprehension and retention of treatment information by the patient, the belief of the treatment information and the weighing up of the information in arriving at a decision.

Current practice: in the absence of capacity

Figure 1 presents an algorithm for current practice, whereby a patient lacks capacity in keeping with guidance from the Medical Council (2016) and HSE (2019). Principles include respecting valid advance directives and a duty to proceed in the ‘best interests’ of patients. In complex scenarios, particularly where there is a dispute around what constitutes best interests, the Courts may be approached for decision-making. The High Court may in some cases invoke Wardship procedures or exercise its Inherent Jurisdiction (Donnelly, Reference Donnelly2009; Gulati et al., Reference Gulati, Whelan, Murphy, Dunne and Kelly2020).

Fig. 1. Current practice.

What will change when the ADMCA 2015 is fully commenced?

The ADMCA was passed in 2015, but most of its substantive provisions have not yet been commenced. Detailed comprehensive reviews of the Act have been performed by Kelly (Reference Kelly2016), Donnelly (Reference Donnelly2016) and Ordinaire (Reference Ordinaire2017). The Act was enacted as part of Ireland’s obligations under the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities 2006. It is expected that some of the substantial parts of the Act may be commenced in late 2020. Certain statutory functions under the Act will be exercised by the Director of the Decision Support Service (DSS), and there will be detailed Codes of Practice produced to assist professionals in applying the Act. The Act will only apply to persons over 18 years of age.

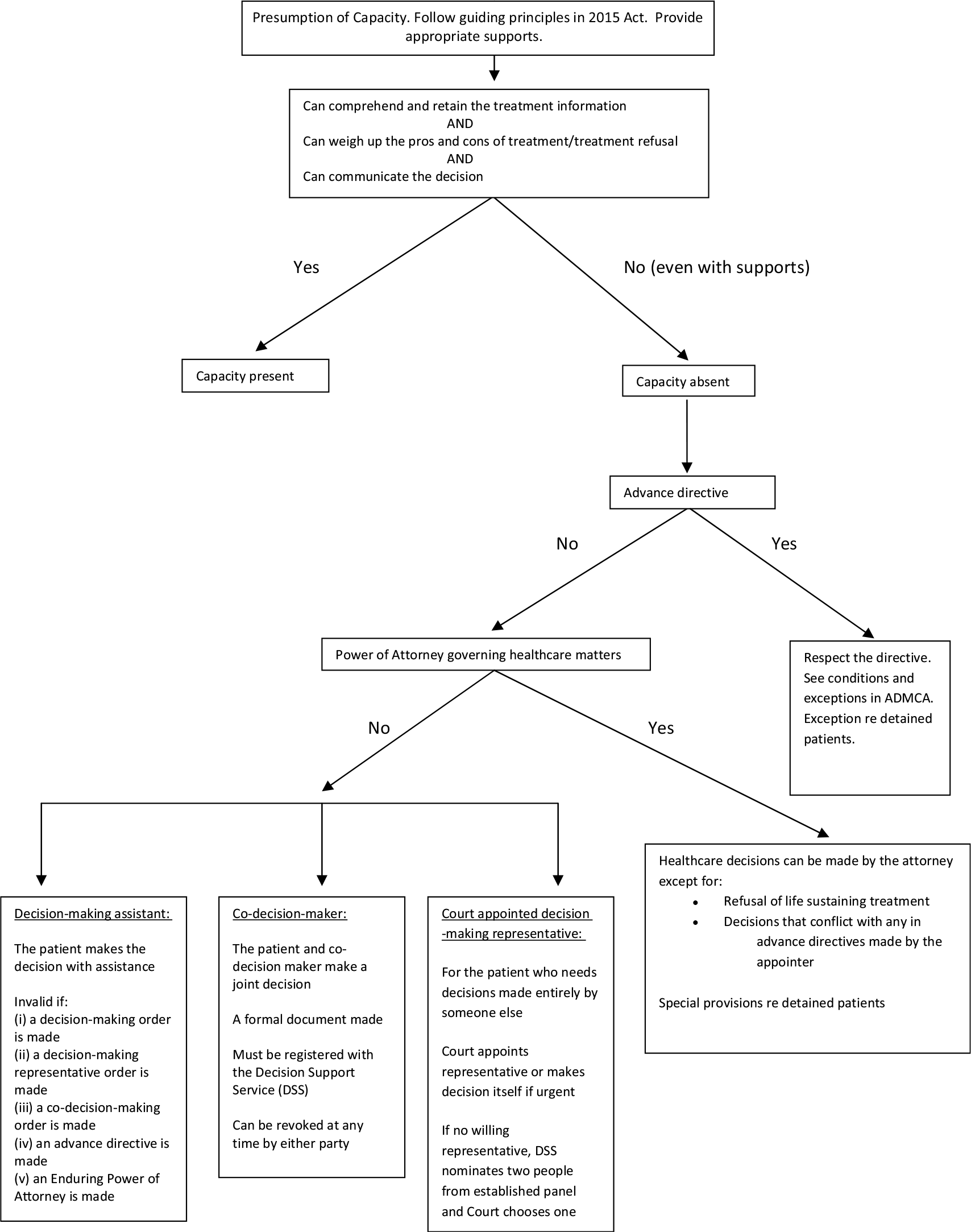

See Fig. 2 for an algorithm that presents practical considerations whereby a patient lacks capacity following commencement of all parts of the ADMCA 2015.

Fig. 2. Practice once all parts of ADMCA 2015 have been commenced.

In essence, there are four key changes that will occur upon commencement:

-

1. While the current approach to capacity is based on the ‘best interests’ of the patient, the ADMCA 2015 will give primacy to the patient’s ‘will and preferences’.

-

2. Currently, the issue of capacity includes the need for the patient to ‘believe’ the information presented to them. This will be removed. There will be a new requirement for the patient to be able to ‘communicate’ their decision in order for the capacity criteria be fulfilled. Communication can be by talking, writing, using sign language, assistive technology or any other means.

-

3. At present, advance healthcare directives are considered under common law. With the commencement of Part 8 of the ADMCA 2015, advance healthcare directives will have a standing in law.

-

4. At the present time, a donee (the appointed individual) of an Enduring Power of Attorney may not make healthcare decisions on behalf of the appointer. With full enactment of the ADMCA 2015, the scope of Enduring Power of Attorney will include certain healthcare decisions. However, such healthcare decisions will not include refusal of life-sustaining treatment or decisions that conflict with advance directives made by the appointer.

The ADMCA 2015 also creates three new types of decision-making. In the event that a patient is found not to have capacity, even when appropriate supports are provided, when there is no advance directive regarding the decision to be made and when there is no Enduring Power of Attorney, there are three possible levels of support:

-

1. A decision-making assistant

-

2. A co-decision-maker

-

3. Court appointed decision-making: a decision-making representative

At the lowest level of supports, the patient alone makes the decision with the assistance of a decision-making assistant who can help to obtain and explain information as well as help the person make and express a decision. The second level of support involves a decision made by both the patient and a co-decision-maker, who also provides support and information. It is a more formal agreement than the first type, with the need for a document to be registered with the DSS (https://www.mhcirl.ie/DSS). At the highest level is a decision-making representative, who is appointed by the Circuit Court to make certain decisions on the patient’s behalf. The Court may, in the case of the need for urgent treatment, make the decision itself. In a case where there is no willing representative, the DSS will nominate two people from an established panel and the Court will choose one of those people.

If the patient is detained in an approved centre under the Mental Health Act 2001 or in a designated centre under the Criminal Law (Insanity) Act 2006, the main provisions of the ADMCA will still apply, but nothing in the ADMCA authorises a person to give the patient treatment for a mental disorder or to consent to the patient being given such treatment.

Conclusions

The ADMCA 2015 is seen largely as a progressive piece of legislation bringing Ireland into line with the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (Oireachtas Library and Research Service, 2017). It uses a human rights-based approach and will supersede Wardship procedures, which are widely regarded as archaic and paternalistic. However, once fully commenced, the ADMCA 2015 will represent a fundamental change in practice for frontline clinicians and, along with this, will bring a period of transition and uncertainty. There is likely to be a need for enhanced training and guidance for clinicians as well as necessity to update the HSE Consent Policy in alignment with the new legislation. This is already underway.

A major challenge will be addressing the need for increased awareness among patients and carers once the ADMCA 2015 is commenced. A change that is very complex for clinicians will likely be as complex, if not more so, for patients and families navigating the altered legislative landscape.

Financial support

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

V.M. is Vice-Chair of the Law Committee at the College of Psychiatrists of Ireland; the views expressed are her own. D.W., C.P.D. and B.D.K. have no conflicts of interest to declare. G.G. is Chair of the Faculty of Forensic Psychiatry at the College of Psychiatrists of Ireland; the views expressed are his own.

Ethical standards statement

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committee on human experimentation with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The authors assert that ethical approval for publication of this Editorial was not required by their local Ethics Committee.