The Mental Health (Care and Treatment) (Scotland) Act 2003 contains major amendments to the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995 that have a direct effect on the assessment and management of mentally disordered offenders. The major developments and provisions of this new legislation are described.

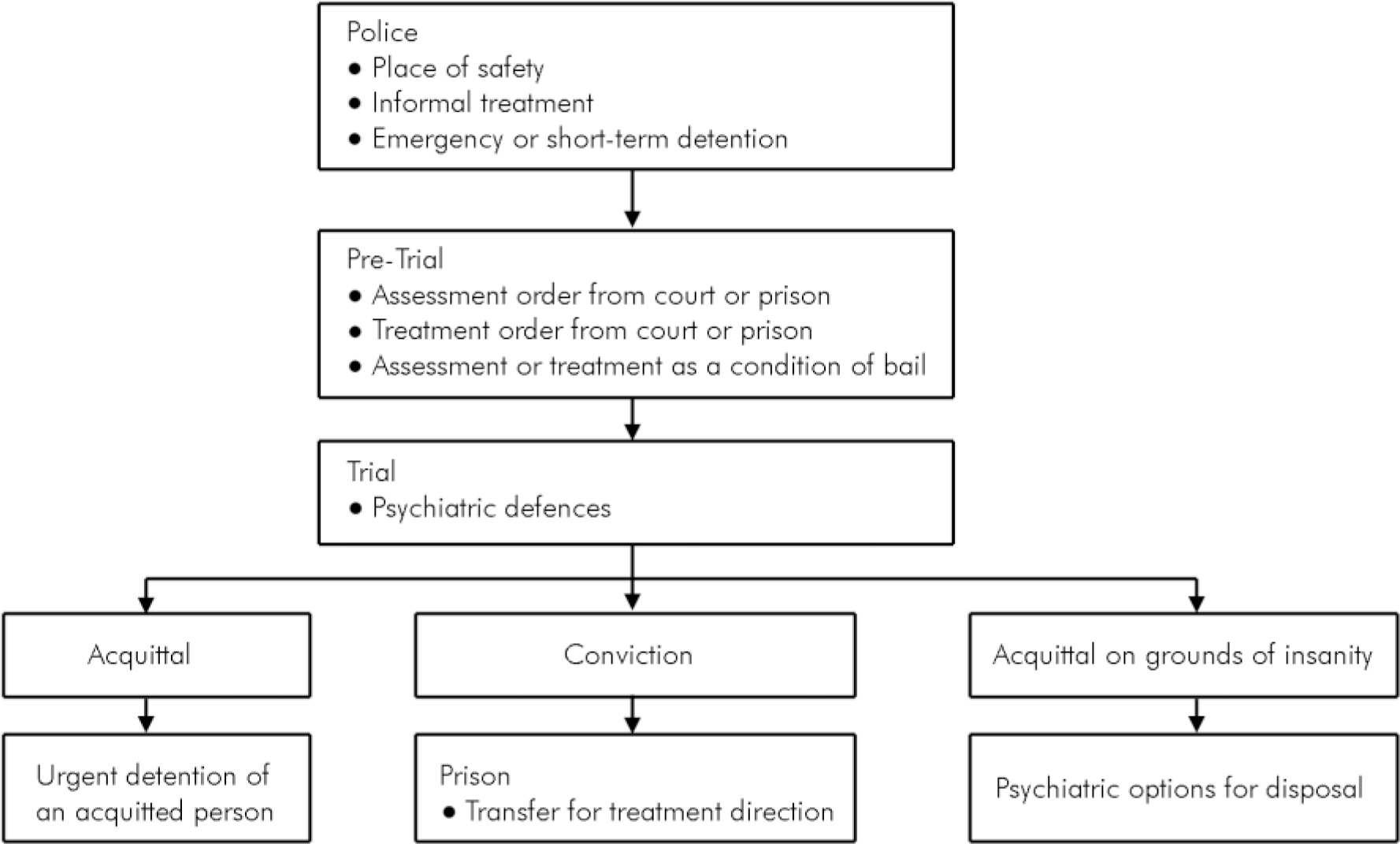

Legislation to ensure the assessment and management of mentally disordered offenders in a health rather than custodial setting is long-standing in Scotland and exists at every stage of the criminal justice process (see Fig. 1). The criminal justice process can continue in tandem with any mental health involvement or at a later date. Individuals can be returned to the criminal justice system unless a final disposal solely to psychiatric services is made. The 2003 Act amends the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995. It brings the 1995 Act into line with the 2003 Act provisions for civil patients, for example, by uncoupling detention and treatment. Further information on the new legislation for mentally disordered offenders can be found in Mental Health and Scots Law in Practice (Reference McManus and ThomsonMcManus & Thomson, 2005) and in the Code of Practice on Forensic Compulsory Powers (Scottish Executive, 2005).

Major developments within the 2003 Act

Principles

The Act sets out underlying principles that must be considered by any person using the provisions of the Act or, indeed, deciding to take no action under the Act. These principles apply equally to mentally disordered offenders and include:

-

• participation of the patient in the process;

-

• respect for carers including consideration of their views and needs;

-

• the use of informal care wherever possible;

-

• the use of the least restrictive alternative;

-

• the need to provide the maximum benefit to the patient;

-

• non-discrimination against a mentally disordered person;

-

• respect for diversity regardless of a patient’s abilities, background and characteristics;

-

• reciprocity in terms of service provision for those subject to the Act;

-

• the welfare for any child with a mental disorder being considered paramount;

-

• equality.

Definition of mental disorder

The 2003 Act defines mental disorder as ‘any mental illness, personality disorder or learning disability however caused or manifested’. A person is not considered to be mentally disordered by reason only of sexual orientation; sexual deviance; transsexualism; transvestism; dependence on or use of alcohol or drugs; behaviour that causes, or is likely to cause, harassment, alarm or distress to any other person; or acting as no prudent person would act (section 328). Personality disorder was added to the Mental Health (Scotland) Act 1984 by the Mental Health (Public Safety and Appeals) (Scotland) Act 1999. Personality disorder was included in the definition of the 2003 Act to allow primarily for the short-term detention of patients with problems secondary to their personality disorder, for example a suicidal individual with a borderline personality disorder. It was not envisaged that there would be a wholesale change in psychiatric practice whereby mentally disordered offenders with a primary diagnosis of a personality disorder were made subject to the provisions of the Act. A recent report on services for people with personality disorder who present a significant risk of physical and psychological harm to others and who come into contact with, or are likely to come into contact with, the criminal justice system outlines proposed services for this group in Scotland (Forensic Mental Health Services Managed Care Network, 2005).

The Mental Health Tribunal for Scotland

The Mental Health Tribunal for Scotland is established by the Act (Part 3). Tribunal members, appointed by Scottish Ministers, include legal representatives, psychiatrists and others with training and active involvement in caring for people with mental disorder. A sheriff will chair all tribunals regarding restricted patients. A tribunal has a major role in the review of compulsion orders, restriction orders, hospital directions and transfer for treatment directions. In addition, it hears appeals against excessive security.

Fig. 1 Interactions between criminal justice and mental health systems

Conditions for detaining mentally disordered offenders

The following medical conditions must be fulfilled for the detention of a mentally disordered offender, but in every case the court must consider all of the known circumstances and any alternative means of dealing with a person.

-

• The patient has a mental disorder.

-

• Medical treatment would be likely to prevent the mental disorder worsening; or alleviate any of the symptoms, or effects, of the disorder; and such treatment must be available (treatability).

-

• Without such medical treatment there would be a significant risk to the health, safety or welfare of the patient; or to the safety of others (risk).

-

• Making the order is necessary.

For civil provisions under the 2003 Act there is an additional criterion that the mental disorder significantly impairs the patient’s ability to make decisions about the provision of such medical treatment. This does not apply to mentally disordered offenders, reducing the threshold for use of the 2003 Act provisions with this group.

Remand to hospital for assessment and treatment

Under the old legislation patients could be remanded to hospital for assessment but there was no provision for treatment, although a system to allow this to occur via a recorded second opinion had been agreed with the Mental Welfare Commission. Under the new legislation there is an assessment order (section 52 D CP (S) A 1995) and a treatment order (section 52 M CP (S) A 1995). Both of these cover the period pre-trial and now also presentencing. In addition, these orders are applicable to people from court and also from prison. For prisoners on remand, following a recommendation from one or more medical practitioners, Scottish Ministers apply to the court that remanded the individual to prison for an assessment or treatment order. Importantly all patients on an assessment or treatment order now have restricted patient status. The criteria for an assessment order do not include treatability and only require that there are reasonable grounds for believing that the person has a mental disorder.

A treatment order allows treatment in hospital pretrial or pre-sentencing and again applies to people from court or prison. On this occasion, written or oral evidence is required from two registered doctors one of whom must be an approved medical practitioner. The treatment order can be applied for directly or following an assessment order. There is no specified period for a treatment order, rather this is fixed by the remand time limits in Scotland (40 days for summary proceedings and 140 days for solemn proceedings).

Compulsion order

The compulsion order (section 57 A CP (S) 1995) replaces the hospital order. Its purpose is to provide treatment of a mental disorder in hospital or in the community. Its civil equivalent is the compulsory treatment order (section 64(4)). A hospital-based compulsion order includes powers to detain in hospital and to give treatment under part 16 of the Act (Reference ThomsonThomson, 2005). A community-based compulsion order includes powers to give medical treatment under part 16 of the Act; a requirement to attend specific or directed places for medical treatment, community care services or any other authorised care, service or treatment, on specific or directed dates or at defined intervals; to reside at a specific place; to permit a mental health officer (MHO), a responsible medical officer (RMO), and others to visit; and to obtain MHO permission to change address prior to any move.

Non-compliance with a compulsion order is treated exactly as with the compulsory treatment order. If a patient under a compulsion order with a requirement to attend for treatment fails to do so, the RMO, following consultation in agreement with the MHO, may take or authorise another person to take the patient into custody and to convey the patient to the agreed place of the attendance requirement or to any hospital where they may be detained for up to 6 h (section 112/176). During this time the patient may be given any medical treatment authorised in the compulsion order, or it can be determined whether the patient is capable and willing to consent to medical treatment. When a patient subject to a compulsion order fails to comply generally with a compulsion order, the patient’s RMO may take or arrange for another person to take the patient into custody and convey the patient to a hospital (section 113/177). The patient’s MHO must give consent. Prior to being taken to hospital the patient must be given a reasonable opportunity to comply with the measures, and it must be considered reasonably likely that there would be a significant deterioration in the patient’s mental health if he was to continue to fail to comply with the measure, and that it is necessary as a matter of urgency to detain the patient in hospital. The patient may be detained in hospital until a medical examination has been carried out as soon as is reasonably practicable. The patient can be detained for up to 72 h. Thereafter a RMO can detain the patient in hospital for up to 28 days (section 114 (2)) pending a review or application for variation following non-compliance with a compulsion order.

Restriction order review

The criteria for a restriction order (section 59 CP(S) A 1995) are unchanged. A compulsion order and a restriction order are appropriate in cases where there is a significant link between the mental disorder and future risk of harm to others. Decisions regarding leave and transfer remain the responsibility of Scottish Ministers but discharge from the order becomes the responsibility of the mental health tribunal. The RMO reports on an annual basis or, if there is a significant change in the patient, to Scottish Ministers. Scottish Ministers can refer cases to the mental health tribunal, and must do so following a recommendation by a RMO, as can the Mental Welfare Commission.

All restricted patients’ cases will be considered at least every 2 years by the tribunal, although further reviews can be requested by Scottish Ministers and the patient or their named person can apply to the tribunal to change an order or grant discharge on an annual basis. The mental health tribunal must consider whether the mental disorder, treatability and risk criteria are fulfilled, and whether a compulsion order, including the need to be detained in hospital, or a restriction order are necessary. In addition, the tribunal must consider whether as a result of the patient’s mental disorder, it is necessary, in order to protect any other person from serious harm, for the patient to be detained in hospital, whether or not for medical treatment. Thus the public safety test introduced in the Mental Health (Public Safety and Appeals) (Scotland) Act 1999 remains in place. The tribunal can order an absolute discharge revoking both compulsion order and restriction order; make a conditional discharge with a defer option to allow arrangements to be put in place; revoke a restriction order and continue or vary the compulsion order; or continue both the compulsion and restriction orders. Scottish Ministers can appeal against any decision and it is not until this appeal period has passed that any order of the tribunal can be enacted.

Standard procedures for mentally disordered offenders

Admission

In general the provisions of the 2003 Act require that patients are admitted within 7 days and that this can be via a place of safety. The powers to convey apply to the police, hospital staff, or others as appointed.

Absconding

If a patient absconds then they can be taken into custody and back to hospital by hospital staff or by the police. The relevant court, if prior to a final disposal, and the Scottish Executive for restricted patients must be informed. A decision to revoke or vary an order may be required.

Suspension of detention

The RMO may suspend detention in hospital by use of a suspension of detention certificate. For patients with restricted status this can only be done with the consent of Scottish Ministers. Detention can be suspended by the RMO for an event or series of events. If the RMO considers it necessary in the interests of the patient, or for the protection of others, the certificate may include conditions, for example that the patient must be kept in the charge of a person authorised in writing for the purpose by the RMO. Time limits apply for suspension of detention for those on a treatment order, interim compulsion order, compulsion order and restriction order, hospital direction and transfer for treatment direction. Detention can be suspended for 6 months on a continuous basis or up to 9 months in any 12-month period. Suspension of detention can be revoked by the RMO or Scottish Ministers.

Urgent detention of an acquitted person

The 2003 Act creates a new provision to urgently detain for medical assessment a person in a place of safety for up to 6 h who has not been convicted but where there are two medical recommendations for a mental health disposal, one by an approved medical practitioner. The conditions of mental disorder, treatability and risk must be met and it must not be practicable to secure an immediate examination. The place of safety will generally be the hospital from which the patient came but this may not be appropriate in some cases, for example when this hospital is a considerable distance from the court, and an agreed local place of safety or the court cells may be used.

Appeals against excessive security

Patients subject to a compulsory treatment order, compulsion order, hospital direction or a transfer for treatment direction may appeal against their detention in conditions of excessive security (sections 264-273 MH (C&T) (S) A 2003). This has only been enacted for high-security hospitals at the present time. The patient, their named person, their guardian or welfare attorney, or the Mental Welfare Commission may apply. Any of these people can apply in the first 6 months of an order and thereafter once every 12-month period. Patients resident in the state hospital must be thought to require conditions of special security and that such conditions can only be provided in a state hospital. The criterion that a state hospital patient must have dangerous, violent or criminal propensities still applies. The appeal is made to the tribunal and the tribunal can agree with the existing order, or give up to 3 months for a health board to identify a lower secure hospital. Scottish Ministers must agree on any proposed setting for restricted patients. If the patient has not moved by the end of the delineated period, there are further hearings; and the Act specifies up to three hearings in total. As long as the tribunal continues to give extensions no appeal can be made to the Court of Session. At the end of the process, the Mental Welfare Commission or the patient can make an application under section 45(b) of the Court of Session Act 1988. This allows for fines and imprisonment in the event of an order not being implemented.

Powers of detention and compulsory measures

The legislation to detain and treat mentally disordered offenders under the 2003 Act as it amends the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) (Act) 1995 is set out in Table 1. This includes comparable sections from the previous legislation.

Table 1. The Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995 as amended by the Mental Health (Care and Treatment) (Scotland) Act 2003: legislation for mentally disordered offenders

| Legal measure | Purpose | Evidence | Psychiatric conditions | Powers | Duration | Duties | Revocation or variation | Previous legislation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment order Section 52 B-J CP (S) A 1995 | Assessment in hospital prior to trial or sentencing From court or prison | Written or oral from one registered doctor | Mental disorder Risk1 Detention in hospital necessary to determine if treatment order criteria met Assessment could not be undertaken if patient not in hospital Bed available in 7 days | Detention in hospital (not treatment) Restricted patient status | 28 days (7-day extension) | RMO — court report MHO — social circumstances report | RMO applies to court | Section 52 CP(S)A 1995—court Section 70 MH(S)A 1984 — prisoners on remand |

| Treatment order Section 52 K-S CP (S) A 1995 | Treatment in hospital pre-trial or pre-sentencing From court or prison | Written or oral from two registered doctors (1 AMP2) | Mental disorder Treatability Risk Bed available in 7 days Can be applied for directly or after an assessment order | Detention in hospital and treatment (part 16)3 Restricted patient status | No time limit — as for remand period | RMO — court report | RMO applies to court | |

| Pre-sentence inquiry into mental or physical condition Section 200 CP (S) A 1995 | To assess mental or physical condition | Written or oral from one registered doctor | Convicted of an offence punishable by imprisonment Needs inquiry into mental or physical condition If hospital proposed — suffering from a mental disorder — suitable hospital placement available Overlap with Section 52 B-J/K-S | To remand a convicted person in custody in prison or hospital, or on bail for assessment of mental or physical condition | 3 weeks (extension for 3 weeks) | Medical/psychiatric report prepared in hospital, community or prison | RMO applies to court | Section 200 CP(S)A 1995 |

| Interim compulsion order Section 53 CP (S) A 1995 | In-patient assessment | Written or oral from two doctors (1 AMP) | Mental disorder Treatability Risk Bed available in 7 days Likely compulsion and restriction orders or hospital direction Not just relevant to state hospital | Detention and treatment in hospital (part 16) | 3-12 months (12-weekly renewal) | RMO — court report MHO — social circumstances report | No procedure/write to court | Section 53 CP(S)A 1995 |

| Compulsion order Section 57 A CP (S) A 1995 | Treatment in hospital or community | Written or oral from two doctors (1 AMP) | Mental disorder Treatability Risk Hospital — bed available in 7 days Convicted of an offence punishable by imprisonment | Part 16 treatment and detention or community attendance, access and residence requirements | 6 months (renewable for 6 months and thereafter annually) | Care plan | RMO, Mental Welfare Commission or tribunal | Section 58 CP(S)A 1995 |

| Restriction order Section 59 CP (S) A 1995 | Control of high-risk patients Combined with in-patient compulsion order | Oral evidence of one medical practitioner | Serious offence Antecedents of individual Risk of further offences as a result of mental disorder if set at large | Detention in hospital Leave and transfer — Scottish Ministers | Without limit of time | RMO (annual) report Scottish Ministers’ duty to review | Tribunal | Section 59 CP(S)A 1995 |

| Hospital direction Section 59A CP (S) A 1995 | Combines hospital detention and prison sentence | Oral or written from two doctors (1 AMP) Doctors can recommend a hospital direction | As compulsion order Link between mental disorder, offence with or without risk of future violence is weak | Detention initially in hospital with transfer to prison available for duration of sentence | Length of prison sentence/compulsory treatment order can follow | RMO (annual) report Scottish Ministers’ duty to review | Scottish Ministers and tribunal Earliest date of liberation Parole | Section 59A CP(S)A 1995 |

| Probation order Section 230 CP (S) A 1995 | Medical or psychological treatments of a mental condition | Oral or written by one registered doctor or a chartered psychologist | Mental disorder — needs treatment Compulsory treatment order or compulsion order not required Patient and criminal justice social worker agree | Attendance for specified treatment | 6 months to 3 years | Liaison with criminal justice social worker Social enquiry report | Agreement of supervising officer Inform court Non-compliance: notification to court | Section 230 CP(S)A 1995 |

| Intervention and guardianship orders Section 60B CP (S) A 1995 Section 58 (1A) CP (S) A 1995 | Personal welfare decisions or management (not financial) | Two medical reports (1 AMP), MHO or chief social work officer report | Found insane or convicted of an offence punishable by imprisonment Mental disorder Compulsion order not required Incapacity for relevant matters Personal welfare issues | Intervention order authorises single decisions Guardianship order provides continuous management | One decision (3 years to indefinite) | Guardians must keep record of decisions | Guardian Sheriff | Section 60B CP (S) A 1995 |

| Urgent detention of an acquitted person Section 134 MH (C&T) (S) A 2003/ Section 60C CP (S) A 1995 | For medical assessment | Two medical recommendations for mental health disposal | Mental disorder Treatability Risk Not convicted Not practicable to secure immediate examination | Detention in a place of safety | 6 h | Medical examination | ||

| Transfer for treatment direction Section 136 MH (C&T) (S) A 2003 | Treatment in hospital of sentenced prisoners | Two medical reports (1 AMP) to Scottish Ministers | Mental disorder Treatability Risk TTD necessary Bed available in 7 days | To transfer and treat in hospital, via a place of safety if necessary Restricted patient status | Length of prison sentence | RMO (annual report) | Scottish Ministers or tribunal Earliest date of liberation Parole | Section 71 ±Section 72 MH(S)A 1984 |

Although few psychiatrists outside forensic mental health are likely to recommend restriction orders or hospital directions, it is essential that all are aware of the provisions for assessment and treatment orders, and for the compulsion order. For colleagues working in different legal jurisdictions where mental health legislation may currently be under review, this paper describes the underlying principles and specific provisions for the detention and/or treatment of mentally disordered offenders in Scotland.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.