Introduction

Established in 2008, the Colorado Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute (CCTSI) at the University of Colorado represents a pivotal effort in linking innovative scientific research with health advancements. Within this framework, the Community Engagement and Health Equity Core (CEHE) is critical to increasing the reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance of clinical and translational research and aims to give communities a voice in the research that is important to them. The CEHE core focuses efforts on community engagement (CE) and Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR), so researchers and partner community members gain foundational skills, apply relevant practices, and have ongoing and responsive support throughout the research and engagement process. Apart from the consistent emphasis within the Requests for Applications from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences for Clinical and Translational Science Award proposals for community engagement as a core activity, the challenges faced by faculty to pursue careers in community-engaged research is well documented [Reference Seifer, Blanchard, Jordan and Gelmon1,Reference DeLugan and Roussos2].

Initiated in 2010 by the CEHE core, the Colorado Immersion Training in Community Engagement (CIT) program aims to introduce an expanded pool of researchers to CBPR, supporting a change in the research trajectory of junior faculty, early career researchers, and doctoral students toward community engagement [Reference Zittleman, Wright and Ortiz3]. CIT creates an infrastructure for educating researchers from a variety of disciplines. Training researchers in the foundations of CBPR aligns with the Clinical and Translational Science Awards initiative of the NIH Roadmap to accelerate the translation of discoveries into everyday practice [Reference Zerhouni4] and is critical to ensuring that health research is not only scientifically rigorous but also culturally sensitive and relevant to community needs. While CIT provides an overview of the community engagement/community-engaged research/CBPR continuum, the focus on CBPR should equip researchers well for engagement along the continuum.

This paper reports the impacts of CIT in its first 10 years (2010–2019). It seeks to assess how effectively CIT has expanded the network of academicians involved in CBPR and understand its broader implications on future programming.

Materials and methods

CIT uses a comprehensive approach of didactic learning and online discussion, experiential learning in partner communities, and Work-in-Progress meetings. The 6-month program is offered once a year at no charge and focuses on between two and five urban and/or rural communities (called community tracks), depending on yearly program funds. Program components include an orientation; 4 weeks of didactic curriculum and discussion about CBPR, historical and current events, and cultural aspects of partner communities; a week-long immersive experience in the partner communities led by CEHE Community Research Liaison (CRL) track leads and local community guides; and 3 months of Work-in-Progress meetings (see Table 1). Often CRL track leads begin mentoring relationships with participants during CIT which last well beyond the program.

Table 1. Colorado immersion training in community engagement activities outline – general 6-month timeline. This table presents the basic outline of a full 6-month colorado immersion training in community engagement (CIT) timeline, including components of the week-intensive agenda. CRL = Community Research Liaison; CBPR = Community-Based Participatory Research

CIT is advertised on the CEHE website, through campus newsletters, and by word of mouth and recommendations from CIT alumni, CRLs, and CEHE program staff. CIT participants apply for the program, identify their preferred track among those offered, and go through an interview process. Applicants must be housed at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus or another CCTSI-affiliated institution and be able to write grants. Candidates will, preferably, be continuing their work post-CIT in Colorado communities. Accepted participants are chosen by CEHE faculty and CRL track leads based on academic focus, expressed interest in CBPR, and track availability. A more detailed description of CIT was previously written by Zittleman et al. [Reference Zittleman, Wright and Ortiz3], and a version of the 2019 CIT curriculum is included as a Supplemental Material 1.

CRL track leads are a critical component of CIT, as multiple CRLs co-developed the program with CEHE staff. CEHE generally has between 8 and 10 CRLs on staff. The CRLs live in geographically dispersed regions of Colorado, represent diverse demographic and social characteristics reflected in Colorado, and were hired because of their extensive community leadership, advocacy, networking, and collaborative excellence with community partners. CRLs receive training in CBPR and translational research and build bridges between health research and community health initiatives while educating others about the purpose and value of equitable and participatory research partnerships. CRLs often assist research investigators in designing locally relevant research studies addressing community needs and facilitate bidirectional communication, partnership development, and culturally immersive learning experiences, including as CIT track leads CRL’s efforts are instrumental in fostering an environment of mutual respect and trust crucial for high-quality research endeavors and the establishment of lasting partnerships aimed at improving the health and well-being of underserved and underrepresented populations.

Evaluation team and overview

The Evaluation Center (TEC) at the University of Colorado Denver conducted the evaluation of CIT. This evaluation, spanning a decade, was determined to be exempt from IRB review, and a 10-year executive summary is available [5]. Three primary methods were employed by TEC for data collection: document review, participant and CRL interviews, and community partner surveys.

Document review

CIT participant reflections

Written reflections were requested from participants upon completing the program each year starting in 2014. Fifty-one reflections (out of a possible 55 participants during that period) were analyzed for evidence of prioritized program outcomes and suggestions for program improvement.

Administrative funding records

Funding records were reviewed to identify CCTSI grant funds acquired by CIT participants after participation in the program. Additional grant acquisition was viewed as one indicator of sustained research engagement.

CIT participant and CRL interviews

Starting in 2016, 42 semi-structured interviews were conducted with past participants 6 months to 2 years post-program completion to allow for the development of relationships and to actualize plans for CBPR outcomes. In 2020, four CRLs were interviewed for historical insights. All interviews were systematically recorded, transcribed, and thematically analyzed using NVivo software [6] focusing on specific program outcomes and emergent themes.

Community partner surveys

CRL track leads and program staff developed a survey to gather feedback from community members integrally involved with CIT to better understand the impact CIT had on their communities. The survey was administered in 2021 using QualtricsXM [7], an online survey platform. CRLs emailed invitations to their CIT community partners containing the survey link and the purpose of the survey. Respondents were offered a $20 gift card in appreciation for their time completing the five-question survey.

Analysis framework

Evaluation data were analyzed using the framework of CBPR principles and Wallerstein’s “Conceptual Logic Model of Community-Based Participatory Research: Processes to Outcomes” logic model [Reference Wallerstein, Oetzel, Duran, Tafoya, Belone, Rae, Minkler and Wallerstein8]. This approach aimed to uncover shifts in researchers’ thinking related to how to conduct research and engage with community and actions taken toward implementing CBPR. The CBPR logic model facilitates a more comprehensive understanding of the program’s impact by outlining potential areas of impact in system change, capacity change, and improved health for communities. The logic model serves as a roadmap for considering how local context and broader social and cultural factors influence social outcomes.

Evaluators utilized the CBPR principles and domains of CBPR during interviews to probe for how researchers talked about the contexts and dynamics of attempting CBPR, as well as to probe for plans or actions taken to implement these learnings into research interventions. The elements of the logic model were also used in the thematic coding of participants’ reflections and the analysis of interview transcripts. These approaches were used to gauge shifts in researchers’ perspectives and actions and to assess long-term impacts, such as changes in policies, practices, power relations, sustained interventions, and improved health disparities and social justice.

Evaluators applied Social Cognitive Career Theory, which correlates increases in knowledge, confidence, and self-efficacy combined with meaningful experiences with stronger intentions and abilities to pursue a career path (i.e., CBPR-informed researcher). Evaluators applied this theory during semi-structured interviews to probe for researchers’ self-efficacy in conducting CBPR, their outcome expectations related to their research impact and career aspirations with a CBPR focus, and beliefs related to structural factors or barriers that may impact a career in CBPR. These theory components were also used during inductive and deductive coding of interviews to gauge researchers’ motivation to pursue a career in CBPR after their CIT experience.

Results

Program participation

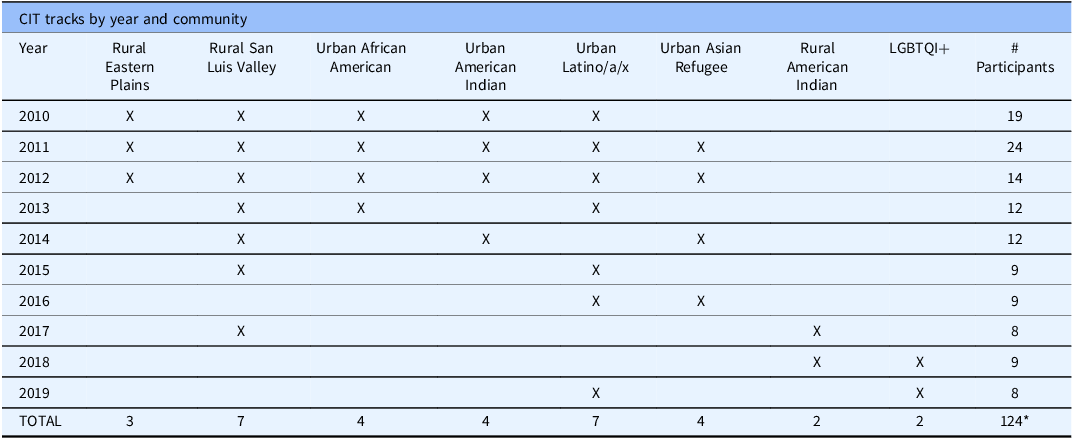

In the first 10 years of programming, CIT engaged 122 academic researchers in CBPR training within 8 diverse Colorado communities. Most participants were from the University of Colorado; however, a few were housed at CCTSI-affiliated institutions such as University of Denver, Colorado State University, Denver Health, and Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. Participant degrees and roles included MD, RN, PhD, NP, MSW, Assistant and Associate Professor, Research Manager, and Postdoctoral Fellow. Many disciplines were represented including Pediatrics, Behavioral Health, Epidemiology, Family and Internal Medicine, Neurology, Health Informatics, and others. Participant demographics, including education, title/role, etc., were not collected over the 10 years in a standardized consistent manner; thus, we do not have complete data. Table 2 shows the number of participants by focus community track offered each year. Throughout CIT, researchers were able to renew or establish perspectives and practices toward community-centered methodologies [Reference Lent, Brown and Hackett9–Reference Pal12].

Table 2. Colorado Immersion Training in Community Engagement (CIT) tracks and number of participants by year. This table provides a yearly overview of the various community tracks and the number of academic participants involved. It effectively showcases the program’s reach and diversity over time, highlighting its extensive engagement with different communities. LGBTQI+ = Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer/Questioning, Intersex

Note *Two academics participated twice; 122 individual participants.

Research productivity

Analysis of research funding received by CIT alumni is an important indicator of the program’s impact. After CIT participation, 23 alumni partnered with community members and/or organizations to receive a CCTSI Community Engagement Pilot Grant. Eleven partnerships received a Partnership Development Grant, a small investment to support academic and community partners to further develop their relationship and explore the potential of a research collaboration. Five alumni with developed community organization partnerships received Joint Pilot Grants, a larger amount for established partnerships to produce preliminary data related to clinical or community interventions in preparation for non-CCTSI external grants. Seven additional researchers and their community partners received both Partnership Development and Joint Pilot funding. These 23 CIT alumni/community partnerships were awarded approximately $4,242,000 in follow-on non-CCTSI grant funding to support their community-based research. In addition, four CIT alumni (two of whom had not received Partnership or Joint Pilot awards) participated in other CCTSI Translational Pilot Grant programs and subsequently received another $4,481,000 in non-CCTSI funding.

In summary, 25 CIT alumni received 33 CCTSI Pilot Grants (both Community Engagement Pilot and Translational Pilot) and were subsequently awarded just over $8,723,000 in non-CCTSI funding.

Career aspirations

Participants reported that the program was instrumental in nurturing new knowledge, providing key contacts and support, and reinforcing the participants’ interest in pursuing CBPR-related work, as predicted by social cognitive theory [Reference Lent, Brown and Hackett9]. For instance, one participant noted that CIT facilitated discussions about the mentor–mentee relationship and identified specific aspects to be aware of when transitioning from a mentee to a mentor role. Another highlighted how the immersion week helped in identifying public health research interests and potential community partners. The impact of CIT on fostering an appreciation for qualitative methods in the research process, particularly storytelling traditions, was also evident in the feedback. Additional examples and quotes are found in Table 3.

Table 3. Colorado Immersion Training in Community Engagement program outcomes – participant perspectives. Findings, themes, and quotes. This table presents key themes and quotes from qualitative analysis of participant interviews and written reflections, including the program’s impact on participants, suggested program enhancements, and challenges experienced in pursuing Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR). CIT = Colorado Immersion Training in Community Engagement; CBPR = Community-Based Participatory Research

Deepened cultural humility and commitment to community

A profound outcome of CIT is the shift in participants’ perspectives, particularly in terms of cultural humility, [Reference Tervalon and Murray-García13–15] and a deepened commitment to community engagement. Participants widely reported a deepening of their understanding and appreciation for cultural humility in conducting research with communities. This change was evident even in researchers who previously had experience with CBPR or community-engaged initiatives.

CIT alumni came to appreciate that CBPR is fundamentally higher quality, due to the diversity of viewpoints and the shift in power dynamics it entails, than traditional research methods. The more informal aspects of CIT, such as sharing meals and participating in daily community activities, were highlighted as equally important as the structured components, providing opportunities for building collaborative partnerships and gaining insights into community life.

Participant suggestions for improving CIT

CIT participants suggested improvements to CIT that would enhance what they gained from the program. As noted in Table 3, evaluation findings consistently show that participants wanted structured opportunities to maintain connection with their cohort of participants and with past participants. They also suggested more educational offerings, mentoring, and more networking opportunities after the immersion experience. Many participants were eager to maintain a network of CBPR-focused individuals, through ongoing online forums, networking events, workshops, or additional mentoring on implementing CBPR.

Challenges in continued pursuit of CBPR

CIT alumni often faced significant challenges, particularly in aligning the intensive nature of CBPR with traditional academic structures [Reference Nyden16–Reference Elwood, Corrigan and Morris18], as indicated in Table 3. The most common challenge cited was navigating academic research, clinical, and teaching productivity requirements alongside the time commitment required for quality, community-driven research. Many participants noted their academic time did not typically allow for the intense time commitment required to develop impactful community-focused research. Some researchers felt their colleagues or departments did not fully understand CBPR or value bidirectional research relationships. Moreover, many outcomes of CBPR, such as tangible community benefits, were not adequately valued in academic circles, particularly in promotion and tenure considerations.

A related challenge commonly encountered by CIT participants was finding appropriate funding streams that align with community-based research. Researchers must frequently contend with grant requirements and funding streams that may not truly value the outcomes of CBPR or that insist on measuring CBPR against standard grant productivity measures ill-fitted to describe community outcomes. Community-based research may identify outcomes such as changes in community policies, repaired relationships, and community-oriented dissemination over academic outcomes, such as journal publications that may not be accessible to community partners. Lastly, evaluation findings consistently show that participants wanted more educational offerings, more mentoring, or more networking opportunities after the immersion experience, as noted in Table 3.

CRL track lead perspectives

Interviews with four of the CRLs who designed and led tracks during 2010–2019 highlighted their role and perspectives of CIT. CRL track leads heavily influenced which tracks were offered each year. They worked meticulously with program staff and their respective communities to develop and execute track-specific activities and curriculum, including curating a selection of historical and current track-specific readings and materials for the didactic component; meeting with community residents and organization leaders to discuss participation and plan visits; and arranging access to places and events of importance to communities. This was possible because of CRLs’ years-long efforts to develop and nurture deep relationships with individuals, organizations, and community groups in their respective communities. CRLs guided researchers’ learnings through exposure to stories, ways of knowing, cultural practices, and beliefs not often accessible to biomedical researchers, thus supporting a shift in traditional academic mindsets toward the values and worldviews present in the community. As noted by the quotes in Table 4, CRLs had expectations of how researchers show up in their communities and witnessed researchers struggling with aligning textbook instruction with often very different realities experienced while immersed in communities.

Table 4. Colorado Immersion Training in Community Engagement program reflections – Community Research Liaison track leads and community partners. This table presents key themes and quotes from qualitative analysis of Community Research Liaison (CRL) interviews and responses to open-ended survey questions asked of community partners engaged in Colorado Immersion Training in Community Engagement (CIT) over the 10-year period. LGBTQ = Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer

Impact of CIT on communities

CIT would not be successful without the partnership of community organizations and individuals who live and work in the track communities. They are well known and respected in their community and engaged in CIT because of their close relationship with CRLs. These partners served in CIT as historians, story tellers, and frontline providers of resources and support for the communities they serve. Thirteen of these formal and informal community leaders from the Urban LGBTQIA+, Asian Refugee, and Latino/a/x, and Rural American Indian tracks were included in the evaluation on the impact of CIT on their communities.

Overall, 78% of community partners reported being “extremely satisfied” with their CIT experience. Just over one-quarter of partner organizations indicated they had not participated in research prior to CIT, with 36% not having participated in CBPR.

Forty-five percent of community partners were aware of research occurring that was a result of relationships built between CIT participants and community members, and 64% were aware of collaborations or projects that had developed because of CIT. Additionally, 55% of community partners were aware of ongoing communication between CIT alumni and their community or organization. Over one-quarter of community partners reported that healthcare or clinical practices in their community have changed “a moderate amount” or “a lot” to be more accessible since partnering with the CIT. Additionally, 64% of surveyed partners reported community members or organizations within their community having a more favorable opinion of university research because of CIT.

Table 4 includes experiences with CIT noted by community partner respondents to open-ended survey questions, in which community partners identified components needed for continued community–academic partnerships and suggested improvements for CIT. These included more opportunity post-CIT for relationship building and continued communication about CIT from CEHE. While change in trust was not quantitatively measured in community partner surveys, the theme of trust routinely surfaced in interviews with CIT participants as well as with the CRLs. As noted in Table 4, one CRL described trust issues with the University of Colorado and work CRLs did to improve trust among themselves and the university followed by trust among community partners and the university. In addition, as noted above under research productivity, many of the community partners engaged with CIT alumni on CCTSI Pilot Grants and funded projects, and some community partners have served on the CEHE governance council, all of which require trusting relationships.

DISCUSSION

CIT’s success in creating an effective educational infrastructure for academic researchers interested in CBPR is evident from the results described. Over its decade-long implementation and extensive engagement in various communities across Colorado, CIT established its initial goals of creating a robust infrastructure for CBPR, expanding the pool of researchers skilled in CBPR from various academic and healthcare institutions and disciplines, and fostering long-lasting partnerships between researchers and communities.

An impressive 20% of CIT participants subsequently developed or enhanced existing community–academic research partnerships through CCTSI Pilot Grants, thereby increasing the research capacity of community organizations and engagement capacity of research institutions.

CRL track leads have the critical role of bringing participants into communities to learn from community leaders who may otherwise be inaccessible to participants. CRLs facilitate these community–academic relationships to build the research capacity of their communities and challenge researchers to embrace cultural ways of knowing and healing.

These impacts show that CIT is a valuable instrument for orienting researchers from traditional research backgrounds toward the benefits of CBPR through facilitation of bidirectional contributions, learning, and unlearning; challenging and transforming researchers’ perspectives; and empowering communities to take a leading role in research that affects them.

In addition to fulfilling many of the early predictions [3], CIT revealed unexpected outcomes. These were the incorporation of CBPR principles into academic curricula, impacting faculty career aspirations and perspectives, together with deep personal transformations. Several CIT participants have become involved in CEHE core programs, including serving as Pilot Grant reviewers, coaches for grant recipients, and members of the community–academic council overseeing the CEHE core. Many CIT participants have engaged with partners outside of their academic role, such as facilitating groups and serving on boards. Community partners serve as advisors to CEHE programming and present about their work at community–academic research forums.

These outcomes highlight the profound and multifaceted impact of the CIT program, extending beyond its immediate goals and reaching into the broader academic and community spheres.

Addressing institutional and funding challenges

While CIT has successfully and positively impacted many researchers toward CBPR and facilitated funding of numerous community–academic partnerships, these results also highlight ongoing challenges CIT participants face within academic infrastructures. The academic research, clinical, and teaching demands of academic institutions and related performance metrics are not conducive to and do not measure time in communities building relationships, incorporating community ways of knowing, and focusing on community-prioritized research questions. As was mentioned in the Introduction, CIT focuses on the components of CBPR, which is further along the community-engaged research continuum than many participants may reach, due in part to time and funding restrictions. However, the training received in CBPR will serve them well in most any community–academic relationship.

This misalignment suggests a need for academia to broaden its evaluation criteria to include CBPR impact, especially for early career researchers who face significant pressure to meet existing academic metrics.

In addition, traditional funding structures often fail to recognize or value the unique infrastructure requirements and outcomes of community-based research, such as policy changes, relationship building, and community-oriented dissemination, which are often not covered under grant funding or under academic time [Reference Nyden16–20]. This disconnect highlights the need for more flexible and inclusive funding models that can accommodate the distinct nature of CBPR and its focus on community-oriented outcomes [20,Reference Sanchez-Youngman, Boursaw and Oetzel21]. Finally, as one moves along the spectrum of community-engaged research, the most effective community outcomes are those in which most of the investment goes into the community itself, rather than the university [Reference Ross, Loup and Nelson19,20,Reference Iton, Ross and Tamber22]. This misalignment underscores the need for structural changes in academia to better support and value CBPR. The challenges of protected time, especially for early career researchers balancing clinical duties and teaching requirements, further emphasize the need for institutional support for CBPR endeavors.

Limitations

The evaluation of CIT largely relied on self-reported measures and retrospective data collection. While these methods provide valuable insights into the participants’ experiences and perceptions and are common for this type of evaluation, they are inherently subjective and may be influenced by recall bias. Additionally, the lack of a control group or comparative data limits the ability to make definitive causal inferences regarding the program’s impact on research productivity and community engagement. Administrative data collection tools and variables changed during the first few years of the program, thus limiting the ability to provide a complete profile of participants and community partners. These metrics have become more standardized over time.

The findings and outcomes may not be directly transferable to other regions or institutions. The specific cultural, socioeconomic, and institutional dynamics of Colorado may have influenced both the implementation of the program and the results observed, thus limiting the generalizability of the findings.

The evaluation covers a 10-year period, which, while substantial, may not fully capture the long-term impacts of CIT on alumni’s careers, community outcomes, and the sustainability of partnerships.

The focus on qualitative outcomes, though rich in detail and depth, is complemented by a less robust quantitative analysis. Metrics such as the number of grants awarded and external funding obtained, while impressive, do not fully encapsulate the broader impacts of the program, including changes in community health outcomes, long-term research collaborations, and institutional changes in support of CBPR.

Future Directions

The future of CIT and similar programs lies in their ability to adapt to the evolving landscape of academic research and community voice in research. Indeed, our evaluations and feedback are an annual part of our process and have resulted in numerous modifications that include increasing the time for reflection, taking more care to ensure that interactions in community are not extractive and expanding participation to those in study coordination roles. Our curriculum is a living document, with adjustments made based on feedback and learnings from prior years. There is a growing recognition of the value of community perspectives and the need for more equitable power dynamics in research. Programs like CIT, which emphasize bidirectional learning and community ownership, are at the forefront of this change. CRLs, CEHE staff, and long-time community partners are building a “Research Readiness” curriculum for community organizations that want to increase their capacity for engaging in CBPR with academics. Given the challenges faced within academic settings, future directions should also include strategies to integrate CBPR more fully into institutional frameworks. This might involve advocating for policy changes, developing new funding structures supportive of CBPR, and promoting institutional recognition of the value of community-engaged research. CEHE has developed a free community engagement consultation service open to both academics and community partners and is working on bringing components of CIT into a variety of course curricula, including that of the Colorado School of Public Health.

Concluding remarks

In conclusion, CIT represents a significant step toward integrating CBPR more deeply into academic research. Its success in training researchers, fostering community partnerships, and co-building programming with communities sets a precedent for other institutions. To replicate CIT’s success, institutions must embrace CBPR values, provide protected time, and establish funding mechanisms that support the unique demands of CBPR. This approach not only benefits academic research but also contributes to building healthier, more equitable communities.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2024.658.

Acknowledgments

The authors, many of whom are CRL track leads, thank the following CCTSI-funded former 2009–2019 track leads: Michelle Wheeler, May Tran, Susan Gale, and Christin Sutter. The authors thank John (Jack) Westfall, Elaine Belansky, Paige Backlund Jarquin, and Victoria Francies for their early contributions to conceptualizing and developing CIT along with CRL track leads and CEHE staff. The authors thank all CIT community partner organizations and guides, too many to name here, who hosted participants in their communities and provided their time, expertise, and stories to make CIT a success. Finally, the authors thank the Trailhead Institute (formerly Colorado Foundation for Public Health and the Environment) for creating and coordinating financial operations for CIT. The author(s) made use of Chat-GPT-4 to assist with the drafting of this article: OpenAI. (2023). ChatGPT (December 2023 version) was accessed from https://chat.openai.com/chat on various dates throughout December 2023 to assist with reducing word count from the original contributions from authors into the final draft of the submitted manuscript; all results were always reviewed by the authors to ensure accuracy.

Author contributions

BWSS, LW, and KG conceived the presented idea. ES performed the evaluation and the analysis. BWSS, LW, RG, MF, and KG drafted the manuscript with support from DN, ES, LZ, CLH, CBO, and LR. All authors contributed to the final version of the manuscript. BWSS takes responsibility for the manuscript as a whole.

Funding statement

The work described in this article is supported by the National Institutes of Health as supplement grant 3UL1RR025780-02S4 under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act and NIH NCATS Colorado CTSA Grant Numbers UL1TR000154, UL1TR001082, UL1TR002535, and UM1TR004399. Contents are the authors’ sole responsibility and do not necessarily represent official NIH views.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.