Introduction

On May 2, 1668, France and Spain concluded the treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, ending the War of Devolution.Footnote 1 On the same day, the doors of the Royal Insurance Chamber (Chambre générale des assurances et grosses aventures) opened on rue Quincampoix in central Paris for the first time. The Chamber—which enjoyed the patronage of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Louis XIV’s eminent minister—quickly emerged as a meeting place in the city for underwriters to sign marine insurance policies. Located “over thirty leagues from the sea,” as Jacques Savary put it in 1675 in his best-selling merchant manual, Le parfait négociant, Paris seems a most unlikely location for a marine insurance market.Footnote 2 Nevertheless, the little-known Chamber flourished in its early years, and Savary encouraged his readers to bring their business here owing to the supposed probity of its underwriters.Footnote 3

On May 3, 1668, Hugues Desanteul passed through the Chamber’s doors, subscribing 500 livres tournois to the Providence’s voyage from Nantes to Liverpool.Footnote 4 He signed his last policy in the Chamber only nine days later; his brother, Henri Desanteul, signed a policy on his behalf on May 16, but before the end of the month, Hugues Desanteul had died.

With the abrupt end of Desanteul’s story, a new one began. On May 30, his widow, Elisabeth Hélissant, entered the Chamber and signed her name on a policy for the first time, underwriting as “the widow of Hugues Desanteul.”Footnote 5 Like other merchant widows, Hélissant had most likely developed her mercantile expertise through actively participating in her husband’s business, so she was well placed to enter the insurance market only days after Desanteul’s death.Footnote 6 She soon emerged as one of the Chamber’s leading underwriters: in both 1668 and 1669, she was the sixth most prolific underwriter in the Chamber in terms of amount underwritten.Footnote 7 The underwriting capital she offered facilitated voyages throughout the Atlantic world (and, to a much lesser extent, the Mediterranean world), with her diverse portfolio ranging from Veracruz in the west to Syria in the east, from Greenland in the north to Buenos Aires in the south.

To date, the striking stories of Hélissant and other female underwriters have not been told. Historians of pre-modern marine insurance have not ascribed any real significance to gender in their analyses. Adrian Leonard’s seminal edited volume from 2016, Marine Insurance: Origins and Institutions, 1300–1850, features no discussion of women in the insurance industry, nor gender more broadly.Footnote 8 This is most likely an issue of sources: put simply, detailed sources on pre-modern insurance are scarce, compounding the perennial challenges of uncovering female agency in sources on commercial activity from this period.Footnote 9 This archival silence weighs especially heavily today, as Lloyd’s of London—the world’s leading insurance market for centuries, with roots in a seventeenth-century coffeehouse—is currently facing a long overdue reckoning, with its history as a homosocial space casting a deep shadow over its current practices.Footnote 10 Female sexual harassment is rife throughout the market, and the gender pay gap in the Corporation of Lloyd’s remains significant.Footnote 11

The Chamber’s extant registers (now kept in the Archives nationales in Paris) thus constitute an invaluable source for the study of female agency in the early modern insurance industry. This article is built on a data set comprising 4153 policies—among the largest in existence for the study of pre-modern marine insurance—which is accessible online through the AveTransRisk (ATR) database.Footnote 12 This data set is based on the Chamber’s surviving policy registers from 1668 to 1672, the outbreak of the Dutch War. Fifty-three underwriting entities (forty-seven individuals and six partnerships/companies) signed more than fifty policies in in this period (i.e., an average of ten policies per year); of these, two individuals were women (one of whom was Hélissant), and one partnership was explicitly multigendered. A small group of other women also participated in the market by constructing more modest underwriting portfolios or serving as commission agents.

While a clear minority, women nevertheless made their mark on the Chamber’s business. Of the 4153 policies signed between 1668 and 1672, at least 1506 (over 36 percent) were signed by at least one female underwriter/multigendered underwriting partnership, with subscriptions from female underwriters/multigendered underwriting partnerships totaling more than a million livres tournois. Footnote 13 Moreover, at least 503 (over 12 percent) involved a female interest, that is, they were signed by a woman as a commission agent and/or had one or more female policyholders.Footnote 14 The data set thus offers an extraordinarily rich insight into the role women played in the Chamber’s life as underwriters, creditors, commission agents, and policyholders. Moreover, drawing on other Chamber registers and the papers of the Parisian admiralty court (formally, the table de marbre of the seat of the admiralty of France in Paris), the article articulates the ways in which women leveraged multiple tools of conflict resolution in service to their interests. Put simply, women could (and did) emerge as leading players in the Parisian marine insurance market. In this way, the article contributes to the growing literature on female agency in the commercial sphere of early modern Europe while simultaneously challenging the long-standing perception that underwriting was an exclusively masculine activity.

Furthermore, the article puts forward Parisian women like Hélissant as notable actors in colonial development, supporting Colbertian projects and overseas ventures at a critical juncture in France’s Atlantic Empire.Footnote 15 The 1660s and 1670s marked a period of intense state support for the development of maritime and colonial commerce, with the Chamber emerging alongside the West India Company (established in 1664), East India Company (1664), Northern Company (1669), and Levant Company (1670).Footnote 16 Within Colbert’s broader economic policy, which strove to reorient Parisian capital toward maritime, commercial, and colonial investment, the Chamber had a key role to play: among the plethora of Atlantic voyages that female underwriting capital and credit propelled were private slaving voyages, permitted by Colbert when the West India Company proved unable to meet colonial demand for enslaved people.Footnote 17 Moreover, female underwriters and multigendered underwriting partnerships even protected the West India Company itself at the outbreak of the Dutch War in 1672. Here, the agency of Parisian women parallels that of women in London and elsewhere in the anglophone Atlantic, which has been explored in depth by Amy Froide and others.Footnote 18 Nevertheless, this agency had its limits: women in the Chamber faced formal and informal barriers that restricted their ability to participate in the institution’s daily life, and the rise of a chartered company in 1686 almost entirely eradicated female agency in the Parisian marine insurance market.

The Royal Insurance Chamber: Women, Portfolios, and Commissions

Using the ATR database, this section explores the activities of female actors in the Chamber as underwriters and commission agents. It tracks how these actors leveraged the Chamber and its resources to build underwriting and commission portfolios that responded to shifts in the political climate over time.

Here, I draw (and build) on a burgeoning literature that is reassessing the role of women in the development of early modern commercial and financial networks and articulating their significance as agents within familial enterprises and as actors with their own economic autonomy.Footnote 19 Similarly, recent works on gender and the institutional history of early modern Paris have stressed the city’s greater accommodation of female labor and capital in comparison to other cities. Paris was the “acknowledged European capital of all-female guilds,” with four such guilds and two mixed-sex guilds in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.Footnote 20 Among the all-female guilds was the seamstresses’ guild, established in 1675 as part of the broader Colbertian reform of the guild system: here, Colbert was in many ways acknowledging the “strong sexual division of labor” that had emerged in prior decades, whereby seamstresses—in defiance of the tailors’ guild’s monopoly—produced clothing for women and children, leaving the tailors to manufacture men’s clothing.Footnote 21 Outside the all-female and mixed-sex guilds—which, after all, represented only a small percentage of all Parisian guilds—the remainder imposed restrictions on female participation, but all (bar the sword makers’ and wine tasters’ guilds) “affirmed the right of a widow to retain and continue to work in her late husband’s shop and workshop.”Footnote 22 Consequently, by the end of the eighteenth century, 7 to 8 percent of all Parisian masters were widows.Footnote 23 Moreover, women (especially widows) were major investors in the French royal debt (rentes in the Hôtel de Ville de Paris), and the development of the notarial system for facilitating private credit brought female capital into the market, with Parisian notaries using their information resources to connect women with reputable borrowers.Footnote 24 In this way, Parisian women were able to build investment portfolios of their own, often with the aim of accruing the resources necessary for a comfortable retirement.Footnote 25 While single women and widows were best placed to make investments in early modern France—on their husbands’ deaths, widows became “heads of households and enjoyed the legal rights associated with that position,” although social pressures often constrained their activities—Julie Hardwick’s work outlines the ways in which married women still exercised considerable agency in local economies, issuing and seeking credit in an age when the household was becoming increasingly intertwined with the market.Footnote 26

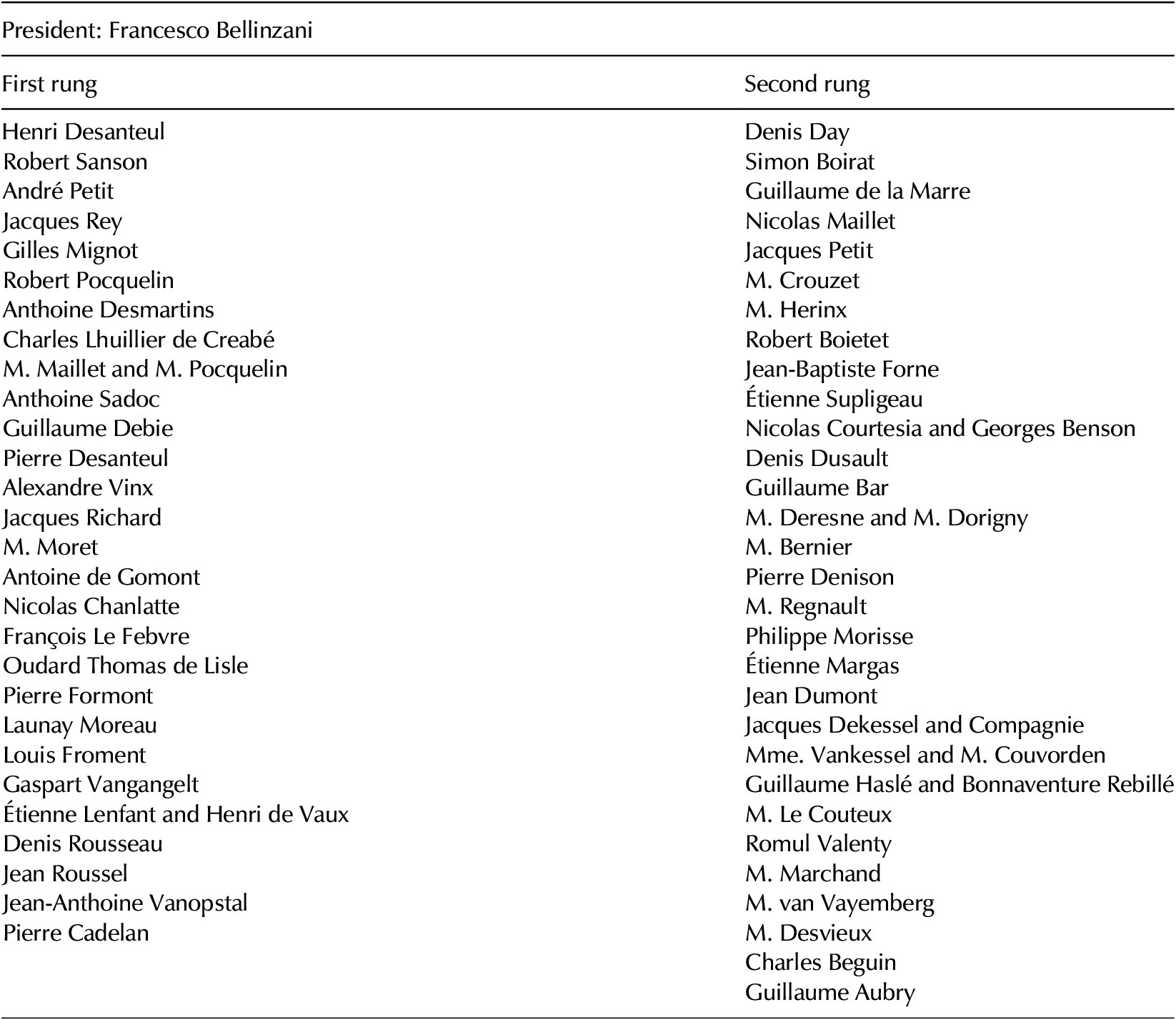

The Royal Insurance Chamber complemented the Colbertian guild reforms and the notarial credit system. It established no barriers to participation: its by-laws enshrined the principle that anybody with a good reputation could conduct business.Footnote 27 Admittedly, a first glance at the Royal Insurance Chamber’s membership list from early 1672 (Table 1) offers little indication of female agency: the list enshrines the Chamber’s highly hierarchical nature, with a core group of thirty men (the first rung of members) recognized as the institution’s leading figures. When the Chamber held meetings to discuss institutional business, these men were guaranteed a seat where others were not, creating a marked spatial division between these men and the other members in accordance with a perceived division in reputation and commercial know-how. As we will see later, these men were typically accorded a leading role in the Chamber’s daily life, especially through resolving disputes as arbiters.Footnote 28 The second rung was reserved for the remaining members who offered their services, be it as an underwriter or as a commission agent. In this rung, a single woman (Mme. Vankessel) is listed. As we will see later, Vankessel was only a modest player in the market, offering her services as a commission agent.

Table 1. The Chamber’s membership, 1672

Source: AN, Z/1d/73, fos. 16ro–17ro.

However, the male-centered list above belies the significance of women in the Chamber’s activities, who, like men, were able to draw on the institution’s resources to conduct their business. All business in the Chamber centered on the registry, where the registrar (Jean Le Roux, then, after his death, Christophe Lalive) received requests for coverage from prospective policyholders or commission agents (the latter of whom secured coverage on behalf of principals located outside Paris) before drawing up the policies and then circulating them within the Chamber for underwriters to sign. Besides keeping exacting records of every insurance transaction through the policy registers on which this article draws, the registrar was also charged with maintaining correspondence with the ports, sharing any news gleaned from these exchanges in the Chamber’s meetings on the second and fourth Thursday of each month.Footnote 29 Furthermore, on Colbert’s instruction, France’s admiralties and foreign consulates were tasked with sending information pertaining to maritime affairs and ship movements to the registry and the Chamber’s president, Francesco Bellinzani, to aid the underwriters’ activities.Footnote 30 While it is impossible to know if either the registrar or the president was selective in revealing news to particular underwriters, an extensive word-of-mouth network of information exchange likely existed within the Chamber that made it hard to keep secrets for long. Moreover, anybody who felt out of the loop could simply choose to follow the lead of the more experienced underwriters by underwriting the policies the latter signed. Thus, female underwriters may not have been guaranteed a seat at the table during the Chamber’s meetings, but the Chamber’s institutional structure ensured they had access to the information they needed to develop sound portfolios. Moreover, women from commercial families could tap into their own networks to inform their decision making as well.

Certainly, men in the Chamber did not doubt the information Parisian women had at their disposal, and even had confidence in the latter’s commercial expertise. André Petit was among the Chamber’s most senior underwriters, but trusted his wife, Françoise Chupin, to sign ninety policies on his behalf between 1668 and 1670, comprising over a third of his portfolio in these years (a total of 264 policies). Chupin’s judgment was sound, as the premium income from these policies of 2714 livres tournois more than outweighed the loss of 500 livres recorded on a single policy.Footnote 31 Chupin maintained a modest portfolio in her own name too: she underwrote five policies in 1669 and sixteen in 1671, totaling 12,800 livres in subscriptions. The Chamber’s registrar was clearly comfortable allowing Chupin to sign contracts in her own name, although (at least theoretically) she would have needed her husband’s express permission to do this.Footnote 32

As we have already seen, Chupin was not the only female underwriter in the Chamber; indeed, she was one of a handful, although she seemed to be the only one who was married (see Table 2). We have already encountered Hélissant, a leading underwriter in the Chamber who put much effort into crafting her portfolio after her husband’s death. Figure 1 tracks her rate of return on capital at risk (hereafter ROCAR rate) as compared with the rate across the Chamber as a whole. This rate—used to good effect elsewhere in the literature—allows us to make meaningful comparisons between portfolios of all shapes and sizes.Footnote 33 It is calculated as follows, using the data summarized in Table 3:

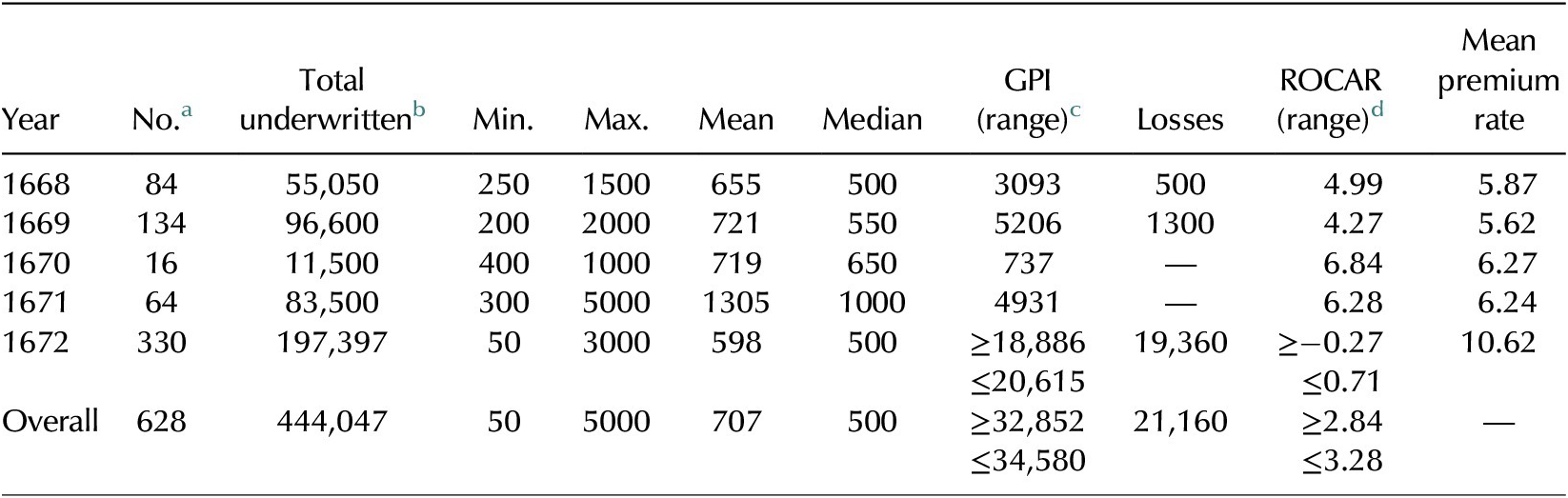

Table 2. The underwriting of the Chamber’s leading female underwriters across the period 1668 to 1672

Source: ATR, based on data from AN, Z/1d/75-8.

a Number of policies signed.

b In livres (as with all the subsequent columns, excluding ROCAR).

c Gross premium income.

d Return on capital at risk.

Figure 1. Elisabeth Hélissant’s underwriting in the years 1668–1672, with the average return on capital at risk (ROCAR; in percent) alongside the Chamber’s average recorded return on capital at risk (in percent). For why these rates are averages, see text.

Source: ATR, based on data from AN, Z/1d/75-78.

Table 3. The underwriting of Elisabeth Hélissant across the period 1668 to 1672

Source: ATR, based on data from AN, Z/1d/75-8.

a Number of policies signed.

b In livres (as with all the subsequent columns, excluding ROCAR and mean premium rate).

c Gross premium income.

d Return on capital at risk.

Hélissant’s early portfolio was remarkably diverse, covering ninety-six different named locations across the Western Hemisphere, but centered heavily on the shipping of Atlantic France, especially the ports of Saint-Malo, Bayonne, and Nantes. Accordingly, the voyages she insured frequently comprised those typical of these ports: Saint-Malo and Bayonne were key hubs for Newfoundland cod fishing, which figured especially prominently in her portfolio.Footnote 34 At the same time, she frequently underwrote Iberian voyages, particularly those centered on Cádiz, which housed a strong French community participating in illicit trade with the Spanish New World.Footnote 35 With this in mind, it is not surprising to see Hélissant joining others in the Chamber in underwriting the Spanish silver fleet to and from Veracruz and Cartagena de Indias.Footnote 36 Underwriters evidently had no qualms about the illegality of this commerce, but Atlantic intermediaries (especially merchants from Saint-Malo) were able to negotiate coverage in Paris without being required to name the beneficiaries of the policies, thereby obscuring the precise details of who was engaging in this trade.Footnote 37

For reasons unknown, Hélissant scaled her underwriting back in 1670. She re-emerged in the Chamber briefly in August 1671, before entrusting her brother-in-law, Henri Desanteul, with her portfolio from October until the end of the year. While Desanteul was signing policies with premium rates that were remarkably consistent with his sister-in-law’s risk appetite from prior years (see Table 3), the subscriptions he made were larger than Hélissant had typically made, with the mean and median subscription in her portfolio almost doubling from the prior year. Because her portfolio was smaller in these years, Hélissant was able to escape with no losses, leaving her a ROCAR rate higher than she had achieved in preceding years.

Yet dark clouds were looming on the horizon. In his quest for gloire on the European stage, Louis XIV had signed the Secret Treaty of Dover in 1670, enshrining a Franco-English military alliance against the Dutch that all but ensured war in the years to follow. In April 1672, Louis declared war; rapid gains in the United Provinces soon gave way to a protracted conflict, leaving France’s Atlantic coastline and its Caribbean and Canadian colonies vulnerable to Dutch privateers.Footnote 38 It was inevitable the Chamber’s underwriting would be transformed by this ubiquitous elevation of risk.

Hélissant took back control of her portfolio in early 1672. By this point, it was an open secret that war was imminent: it was only a matter of when war would be declared.Footnote 39 In this climate, Hélissant made prudent decisions to try to prevent major wartime losses. Following a common underwriting strategy (as we will see later), she dramatically increased the size of her portfolio: her subscriptions for the year totaled 197,397 livres, more than double the size of her portfolio at its prior peak in 1669. Yet she made smaller subscriptions to the policies she did sign, with her mean and median subscriptions consequently falling to 598 and 500 livres, respectively (see Table 3). In short, she signed many more policies than ever before (indeed, more than she had signed in the years 1668 to 1671 combined), but for smaller amounts. The strategy was clear: Hélissant was spreading her exposure to risk, hoping that her premium income would cover the (smaller) losses that would inevitably follow from insuring so widely with the outbreak of war.

To an extent, she also tried to diversify her portfolio, which now covered 125 named places in the Western Hemisphere. Still, as we can see in Figure 2, Atlantic ports (namely Le Havre, La Rochelle, Bordeaux, and Bayonne) underpinned the portfolio in 1672. Moreover, her portfolio became imbalanced through a focus on three particular types of voyage: cod fishing voyages in Newfoundland, whaling voyages in Greenland, and the reinsurance of voyages in the Mediterranean.

Figure 2. Elisabeth Hélissant’s underwriting portfolio in 1672. The size of the circles corresponds with how frequently each port/place/country (as named in each policy) appeared in her portfolio. NB: Buenos Aires is not included in the image.

Source: ATR, Google Maps.

In underwriting Newfoundland fishing voyages and Greenland whaling voyages, Hélissant and other underwriters supported the training and employment of novice mariners—essential to the state in creating a pool of sailors that could sustain overseas commerce and serve in the French navy.Footnote 40 Newfoundland cod was often transported to the Mediterranean for sale in the markets of Iberia, southern France, and Italy, while whales were a source of various materials (chiefly, whale oil, used to make soap) that facilitated French and Dutch industry.Footnote 41 Yet the long Atlantic journeys these operations required left vessels exposed after the outbreak of war, prompting merchants, investors, and shipowners to seek coverage from the Chamber, which Hélissant and other underwriters willingly provided.Footnote 42

Perhaps recognizing the risks they were bearing in the Atlantic, Hélissant and others tried to rebalance their portfolios through reinsuring Mediterranean voyages, which had different risk profiles. The principal source of this business was Pierre de la Roche, a French merchant based in Venice who reinsured policies he signed there through a Parisian commission agent. Yet these efforts backfired: North African corsairs succeeded in a series of captures, resulting in losses that compounded those sustained in the rest of the portfolio.Footnote 43

Did Hélissant manage to emerge from the year in the black, despite these losses? It is impossible to say for sure: in late 1671 and early 1672, underwriters in the Chamber started inserting war clauses into their contracts, requiring policyholders to pay an agreed augmentation in the premium in the event war broke out.Footnote 44 The Chamber’s policy registers do not make clear if these clauses were ultimately triggered or not for each policy. Thus, in Table 3, I express Hélissant’s gross premium income (GPI) as a range (the smallest figure assuming these clauses were never triggered and the largest assuming the clauses were triggered in every case) and use the mean to display the ROCAR rate in Figure 1. Her losses from the year totaled 19,360 livres, but her GPI could have been as little as 18,886 livres (an uncomfortable loss of 474 livres, but not catastrophic in comparison to other underwriters in the Chamber, as we will see) or as great as 20,615 livres (leaving a quite handsome profit of 1255 livres).

While her returns for the year are ambiguous, Hélissant certainly fared better than other widows following the outbreak of war. Elisabeth Lefebvre (known in the Chamber’s policy registers as “Widow Lescot”) entered the Chamber in 1671 with a modest portfolio; like Hélissant, she likely treated underwriting as a means of diversifying her commercial investments.Footnote 45 Having dipped her toe in the water in 1671, and sustained no losses, she made the fateful decision to gamble on war risks. While it was common for underwriters to withdraw from the market in the face of war, with little appetite for the uncertainty it brought, others joined in the hopes of making speedy profits from high premiums.Footnote 46 Lefebvre was among them: her portfolio amounted to 62,050 livres in 1672, centering on Newfoundland, Greenland, Iberian, and Mediterranean voyages (see Figure 3). The mean premium rate for the policies she signed sat 1.8 percent above the mean across all the Chamber’s policies, indicating a conscious decision to create a riskier portfolio (see Figure 4). This did not pay off, and her losses vastly outweighed her GPI: her ROCAR rate fell below −3 percent for the year, leaving her at least 1700 livres in the red (see Table 4).

Figure 3. Elisabeth Lefebvre’s underwriting in the years 1671–1672, with the average return on capital at risk (ROCAR; in percent) alongside the Chamber’s average recorded return on capital at risk (in percent).

Source: ATR, based on data from AN, Z/1d/75-78.

Figure 4. The average premium rate of the policies signed by Elisabeth Lefebvre in the years 1671 to 1672, alongside the average of all the Chamber’s policies.

Source: ATR, based on data from AN, Z/1d/75-78.

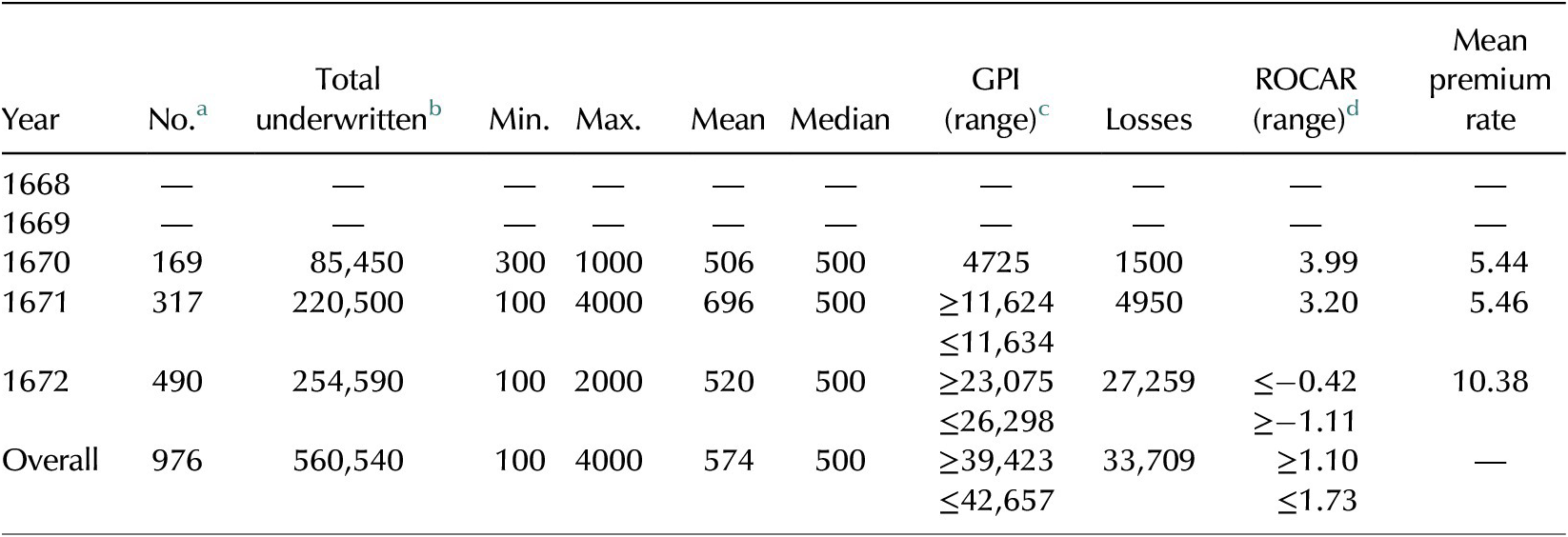

Table 4. The underwriting of Elisabeth Lefebvre across the period 1668 to 1672

Source: ATR, based on data from AN, Z/1d/75-8.

a Number of policies signed.

b In livres (as with all the subsequent columns, excluding ROCAR and mean premium rate).

c Gross premium income.

d Return on capital at risk.

Thus, while Hélissant developed a deep portfolio that ran over several years—thereby helping to cushion any losses she might have sustained in 1672—Lefebvre put together a speculative portfolio that ultimately served her poorly. Alongside numerous colleagues, she learned the hard way that marine insurance was a dangerous market for speculation.Footnote 47

While Jean-Anthoine Vanopstal was listed as one of the Chamber’s leading members in 1672 (see Table 1), he was underwriting in partnership with his mother-in-law, Anne Jousse (known in the Chamber’s policy registers as “Madame Coulart,” widow of Jacques Coulart).Footnote 48 Jousse and Vanopstal entered the market in 1670 with a remarkably diverse portfolio. Nevertheless, Iberian and Caribbean voyages emerged as key foci in 1670 and 1671, reflecting broader trends in the commerce of Atlantic France.Footnote 49

Moving into 1672, Jousse and Vanopstal changed tack. The story by now is familiar: they grew their portfolio, focusing especially on Newfoundland, Greenland, and Venice as Hélissant and other leading underwriters had done. The partnership emerged at least 1000 livres in the red for the year (see Figure 5).Footnote 50

Figure 5. Anne Jousse and Jean-Anthoine Vanopstal’s underwriting in the years 1670–1672, with the average return on capital at risk (ROCAR; in percent) alongside the Chamber’s average recorded return on capital at risk (in percent).

Source: ATR, based on data from AN, Z/1d/75-78.

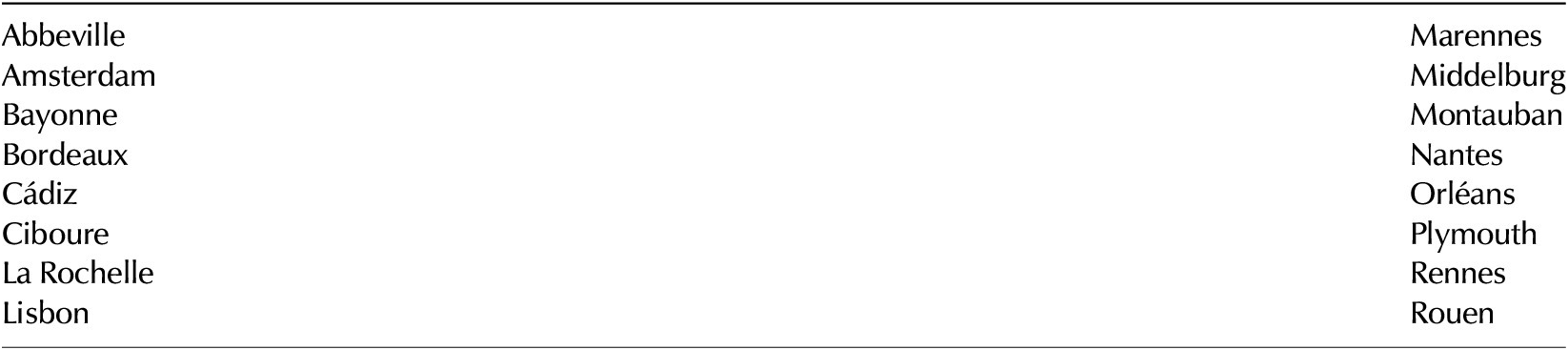

While 1672 proved a challenging year, Jousse and Vanopstal’s premium income from 1670 and 1671 ensured positive returns across the period 1670 to 1672, with profits running to at least 5700 livres overall (see Table 5). Moreover, they supplemented their income through offering their services as commission agents to merchants based in France, England, Spain, Portugal, and the United Provinces (see Table 6). In total, Jousse and Vanopstal were responsible for 239 policies (5.7 percent) of all the Chamber’s policies up to 1672, either securing coverage on behalf of others (principals) as commission agents or for their own account.Footnote 51 Evidently, Jousse and her son-in-law had diverse commercial connections and maintained strong correspondence across numerous countries in order to sustain this commission portfolio. Meanwhile, Mme. Vankessel—the only woman named in the Chamber’s table of members, for reasons that are unclear—worked with M. Couvorden to secure eighty-six policies for principals in Abbeville, Amiens, Bordeaux, Calais, Lille, and Saint-Valery-sur-Somme.Footnote 52 Similarly, Mlle. Rondeau signed forty policies as a commission agent for principals in Abbeville, Alicante, Bayonne, Bordeaux, Calais, Montpellier, and Nantes.Footnote 53 These policies therefore hinged on multigendered networks, with Jousse, Vankessel, and Rondeau serving as nodes linking the supply of insurance coverage in Paris with demand in France and beyond.

Table 5. The underwriting of Anne Jousse and Jean-Anthoine Vanopstal across the period 1668 to 1672

Source: ATR, based on data from AN, Z/1d/75-8.

a Number of policies signed.

b In livres (as with all the subsequent columns, excluding ROCAR and mean premium rate).

c Gross premium income.

d Return on capital at risk.

Table 6. The named locations of principals for whom Anne Jousse and Jean-Anthoine Vanopstal signed policies in the Chamber

Source: ATR, based on data from AN, Z/1d/75-78.

The Chamber thus facilitated a range of activities for female actors, offering interesting parallels with the stock market in the British Financial Revolution. In many ways reminiscent of Hélissant and Jousse, Johanna Cock worked shoulder to shoulder with men while trading extensively in Bank of England and East India Company shares before and during the 1720 South Sea Bubble.Footnote 54 Yet Cock was an outlier, with most other women engaging only modestly and/or sporadically with the market (rather like Chupin or Rondeau) or engaging primarily to speculate (rather like Lefebvre).Footnote 55 Thus, Paris and London alike offered women the opportunity to participate in the market based on their resources and risk appetites.

In turn, the underwriting of women in the Chamber also proved useful to state interests in supporting maritime commerce, the Atlantic slave trade, and the activities of France’s chartered companies. Bellinzani, the Chamber’s president and Colbert’s right-hand man in commercial affairs, was ideally placed to lean on members to provide coverage and capital for corporate and private voyages enjoying Colbert’s patronage. In late 1671, in his capacity as Northern Company director, Bellinzani secured 100,000 livres of coverage on two of the company’s vessels. One of these vessels was underwritten by Jousse, Vanopstal, and Lefebvre.Footnote 56 More curious are a series of policies secured by the Levant Company the same year. One voyage from Istanbul to Marseille was underwritten by Jousse and Vanopstal; the other voyages, however, had no relation to the Levant whatsoever: three revolved around Newfoundland fishing, while another centered on the Caribbean; all, again, were underwritten by Jousse and Vanopstal.Footnote 57

This underwriting speaks to the porosity and flexibility of corporate privileges under Colbert: theoretically, voyages to the Caribbean came under the sole remit of the West India Company. Established by Colbert in 1664, this company ostensibly had a monopoly over all French trade with western Africa and the Americas, tasked primarily with providing enslaved people to the Caribbean colonies.Footnote 58 By 1669, however, it had failed to make the impact Colbert had hoped: the governor of Martinique wrote to the minister to complain the company was failing to meet the demand for enslaved people in the colonies. In response to this, Colbert authorized a series of private slave voyages from 1669 to 1672.Footnote 59 The Levant Company’s voyage to the Caribbean may well have been authorized within the context of this gradual breakdown in the West India Company’s operations. Far from being dogmatically wedded to corporate privileges, Colbert was willing to open markets under monopoly up to new groups when chartered companies were unable to serve state interests.Footnote 60

Evidence of this can be seen in how Colbert was able to lean on the Chamber to support private slave voyages. Bellinzani, Claude Gueston, Jacques Rey (all underwriters in the Chamber), and other unnamed parties invested directly in the Saint Esprit’s successful triangular voyage from Le Havre to Guinea, the Caribbean, and then back to Le Havre. On August 29, 1670, Jousse and Vanopstal subscribed 1000 livres to the policy on this voyage. The policy, totaling 50,500 livres, covered (among other things) enslaved people (nègres) as “merchandise.”Footnote 61

Despite the erosion of its monopoly privileges, the West India Company continued to operate, and in 1672, women in the Chamber bore some of its risks in the Caribbean. Following the outbreak of war on April 7, the company’s ships were left exposed on their return journeys to France. The company’s directors thus came to the Chamber on April 25, securing 267,600 livres of coverage on eight of its vessels and the sugar with which these were laden. Almost a tenth of this coverage was provided by Jousse, Vanopstal, Hélissant, and Lefebvre, each gambling that the vessels they underwrote would return safely with the support of a newly instituted naval convoy system (see Table 7).Footnote 62 Mercifully for the underwriters, every vessel reached France without incident.Footnote 63

Table 7. The policies secured by the West India Company on April 25, 1672

Source: ATR, based on data from AN, Z/1d/75-8.

Conflict Resolution and the Limits of Female Agency

The West India Company’s need for such extensive coverage reflects the reality that voyages in the seventeenth-century world were often not smooth sailing, especially in times of war. This is precisely why marine insurance existed: underwriters agreed to bear the losses when things went wrong. Getting underwriters to follow through on their commitments, however, could be challenging: in Le parfait négociant, Savary cautioned his readers to exercise care when choosing an underwriter, as rogue insurers could simply refuse to make payment and drag out litigation to the detriment of the policyholder.Footnote 64 Similarly, policyholders could conspire to defraud their insurers: in a diary entry from December 1663, Samuel Pepys reflected on a case at King’s Bench in London whereby a shipmaster insured his ship and merchandise for more than they were worth, then left his ship to wreck off the coast of France in the hopes of claiming a handsome payout.Footnote 65 Even between these extremes, conflict was inevitable from time to time, as parties debated events at sea in relation to the provisions of insurance policies and maritime law.Footnote 66

Here, men and women alike had choices. The sociological turn in the study of legal practice has led to a reassessment of courts in Old Regime France, with scholars now treating litigants as consumers of justice who became agents of state formation through the decisions they made in resolving conflicts.Footnote 67 This section considers the women operating in the Chamber in the same way: it explores how, as legal actors, these women adopted different strategies to best serve their interests.

In the first instance, disputants might wish to engage in private talks to try to find a mutually agreeable solution. These informal negotiations do not always leave a trace in the historical record, but in some instances, parties asked the Chamber’s registrar to record agreements for the benefit of all involved.

In September and October 1671, on behalf of a group of unknown stakeholders, Jousse and Vanopstal sought backers in the Chamber for a series of sea loans. Unlike a typical loan, the principal and interest on a sea loan were paid back only in the event of the safe completion of a given voyage.Footnote 68 The voyage in question was that of the Saint François, which was set to sail from La Rochelle to “the coast of Guinea” to “trade” there, before traveling to the French Caribbean islands and thence back to La Rochelle.Footnote 69 This was, in short, a textbook triangular slaving voyage—presumably, one of the private ventures authorized by Colbert.

Marie de Longueuil, marquise de Soyécourt, was one of eight who agreed to invest in the voyage. When the Saint François reached the Caribbean, it was stopped “for the King’s service” and then subsequently forced by the French governor to wait for more than two months for an escort to arrive. (Whether this royal service impinged on the trading activities the vessel intended to undertake in the Caribbean is unclear.) Jousse and Vanopstal liaised with Soyécourt and the other creditors in July 1673 to request a discount on the interest the debtors owed for the loans, to which the creditors consented. Both groups agreed to record this agreement before the Chamber’s registrar on July 11: Soyécourt was the first to sign her name, even before the Chamber’s senior male members, perhaps reflecting her social rank. Through this agreement, the parties were able to part on good terms.Footnote 70

Otherwise, disputants could come before arbiters in the Chamber’s own arbitration chamber to bring conflicts to a speedy and amicable close. In this space, the agency of women varied based on their role in a given conflict. Nevertheless, looking at the surviving register where the details of arbitration conflicts were recorded, it becomes clear women could, and did, present themselves, their arguments, and their evidence in this chamber.

On June 25, 1672, Catherine Carré, the widow of a Rouennais merchant named Robert Buffier, came to the Chamber seeking 9000 livres of coverage from the Chamber’s underwriters.Footnote 71 On April 30, Dirick Gautier had purchased merchandise for her in Gdánsk and sent it to Jacques Martin in Hamburg via Lübeck. The merchandise arrived safely in Hamburg and was received by Martin, who loaded it on the Concorde, whose shipmaster was Gert Jensen Boorman, alongside other merchandise he had bought on Carré’s behalf. On May 20, he wrote to Carré to inform her of the merchandise he was sending on Boorman’s vessel, which was bound for Rouen. This gave Carré the opportunity to secure insurance coverage in Paris. However, a mistake was apparently introduced either before or during the process of drawing up the policy: it specified coverage for the vessel of Jean Georges Boorman, not Gert Jensen Boorman.Footnote 72

As the Concorde tried to navigate the Seine to reach Rouen, the vessel ran aground, resulting in the partial loss of its cargo. Moreover, other unspecified damages were incurred, for which all stakeholders were required to contribute through a legal instrument known as general average.Footnote 73 In addition to her own losses, Carré’s general average contribution amounted to 158 livres 17 sols 3 deniers. Nevertheless, when she sought compensation from her Parisian underwriters, they refused to pay out based on a technicality. (Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.) The policy did not apply, they argued, because the shipmaster’s name on the policy was incorrect.Footnote 74

Carré and the underwriters agreed to meet before arbiters, who assembled on April 18, 1673, to hear their arguments. Carré, speaking alone on her own behalf, came prepared: she submitted fourteen documents to the arbiters justifying her interest in the Concorde, including a series of receipts, bills of lading, letters, notarized declarations, and even a statement from a group of senior Rouennais merchants testifying to the Concorde’s grounding. The arbitration register does not outline the underwriters’ submission in detail; however, it seems they argued that if Jean Georges Boorman was a real shipmaster, they could not be held liable. They most likely justified this by suggesting that, if they were held liable, this could open the underwriters up to fraudulent claims in the future.

Sorting through the paperwork she had provided, the arbiters concluded the underwriters owed Carré 40 percent of what they had insured (amounting to 3600 livres). Acknowledging that the shipmaster was not correctly named in the policy, however, Carré was required within three months to produce a suitable certificate attesting that there was no shipmaster named Jean Georges Boorman in Hamburg. In the meantime, if she wanted to be paid, she was obliged to find herself a guarantor—that is, someone who was willing to be held liable for Carré’s payout if she could not produce the required certificate and became insolvent in the meantime.Footnote 75 Unfazed, Carré returned to the Chamber three days later with Simon Levesque, a Parisian merchant who agreed to act as her guarantor.Footnote 76 On July 17, Levesque was released from his obligations as guarantor, with the underwriters acknowledging receipt of a certificate confirming that “there is no master in Hamburg named Jean Georges Boorman.”Footnote 77 Thus, while the dispute lacked the drama of Eleanor Curzon’s successful lawsuit against the South Sea Company in the aftermath of the 1720 Bubble, Carré’s defense in the arbitration chamber was still impressive: it attested to her ability to argue confidently for her interests, bringing the paperwork needed to persuade the arbiters she was acting in good faith and was worthy of indemnification.Footnote 78

Carré was not alone. As a leading commission agent in the Chamber, Jousse appeared in the arbitration chamber alongside her son-in-law to present arguments on behalf of their principals—although, on some occasions, Vanopstal appeared before the arbiters alone.Footnote 79 On January 24, 1669, both signed a policy on behalf of Charles Alleanne of Rouen and other unnamed parties for the Esperance’s voyage from Bilbao to Le Havre or Rouen.Footnote 80 The Esperance encountered strong winds between Le Havre and Calais, obliging the crew to cut a cable. The vessel reached Calais, but not without the loss of some merchandise. General average was assessed in Le Havre on March 15 at 3 percent for both the ship and the merchandise.Footnote 81 In arbitration, the underwriters argued that, following the provisions of the Guidon de la mer (a sixteenth-century Rouennais compilation of maritime law and custom), they were not liable for damages of less than 5 percent when these arose from storms.Footnote 82

Jousse and Vanopstal pushed back against this argument. Working with other disputants who had a stake in the same vessel, they argued that the practice outlined by the underwriters was “contrary not only to [the practices of] Holland, Hamburg and other foreign states, but also to [those of] Rouen and the other principal ports of the kingdom,” such as Saint-Malo and Bordeaux, where payment was permitted for damages arising from storms below 5 percent.Footnote 83 To support this claim, Jousse and Vanopstal submitted a policy signed in Rouen for the same voyage: Rouennais underwriters, it transpires, had made payment on this policy without complaint. In the end, the in-laws prevailed, with the arbiters ordering the insurers to make payment on the claim within three days in deference to the Rouennais’ decision to pay out.Footnote 84

They proved successful on other occasions too. On June 2, 1670, twenty separate underwriting entities insured the Esperance’s voyage from Le Havre to Cádiz. Before arbiters in November, Jousse and Vanopstal—acting as commission agents for a company in Orléans—presented abundant evidence to substantiate the vessel’s capture by Salé corsairs. This included a certificate issued by François Julien-Parasol, consul to the French nation in Salé, acknowledging the capture. They also submitted bills of lading and other documents to justify the company’s interest in the adventure. In the face of this evidence, the underwriters made no argument; they had “no means” of disputing their liability, and the judgment requiring them to make payment duly followed.Footnote 85 In short, Jousse and Vanopstal were seasoned players in the market and were able to secure the necessary documentation from their principals to support their claims.

Jousse and Vanopstal’s underwriting activities occasionally overlapped with their activities as commission agents—that is to say, they chose to underwrite some of the policies they brought to the Chamber. In two instances, when conflicts arose between the principals and the other underwriters in the Chamber, Jousse and Vanopstal found themselves in the uncomfortable position of entering arbitration disputes as claimants and defendants simultaneously.Footnote 86 Nevertheless, the principals clearly trusted their commission agents to represent their interests, even in these unusual circumstances.

Jousse’s capacity to contribute to conflict resolution in the Chamber had its limits. On occasions, Vanopstal served as an arbiter, helping to bring disputes in the Chamber to a mutually acceptable close; Jousse, by contrast, never served in this function, nor did any other woman.Footnote 87 While the Chamber’s by-laws did not explicitly exclude women from arbitrating disputes, the institution seemed to introduce its own informal barrier here to female participation.Footnote 88 This offers some interesting parallels with the formal and informal constraints on female agency within the guild system.

It is hard to say how far the women who served as underwriters were able to contribute to arguments presented before the arbiters. The Chamber’s arbitration register typically refers to the underwriters only as claimants or as defendants throughout the record of each case, seldom giving an insight into who was speaking. In the rare instances in which underwriters were explicitly identified as speaking on behalf of others, it was senior male underwriters who had taken up this role, in keeping with the Chamber’s hierarchical structure.Footnote 89 Indeed, when Carré presented her case for the damages she had sustained when the Concorde grounded in the Seine, Hélissant—who had underwritten this voyage—was not even in the arbitration chamber: Henri Desanteul, André Petit, Alexandre Vinx, and Denis Rousseau spoke on behalf of her and the other underwriters with an interest in the policy.Footnote 90 Thus, while female underwriters may have been able to help in formulating arguments in advance of arbitration, they were ultimately reliant on the senior male underwriters to present these arguments effectively once they entered the arbitration chamber.

Arbitration was not the only possible venue for addressing conflicts, however, which gave female agents in the Chamber further scope to manage conflicts themselves. The Parisian admiralty court handled insurance conflicts, especially in 1673, reflecting the glut of losses that followed the outbreak of war in 1672. Among the cases brought before the court in 1673 was that of Catherine de Lasson, a widow from Saint-Jean-de-Luz. While Lasson had a Parisian commission agent, Paul Aceré des Forges, she chose to take matters into her own hands when underwriters refused to pay out on her policy: at the cost of 30 livres, she sent a horseman from Saint-Jean-de-Luz to Paris to submit her petition to the admiralty court. On July 31, the court ruled in her favor, requiring the underwriters to pay out on the policy and to reimburse her expenses—including the cost of the horseman.Footnote 91 Thus, Lasson had eschewed the Chamber’s arbitration system in favor of the admiralty court, which, presumably, she felt more confident would meet her needs as a litigant. By contrast, I have found no evidence that Jousse and Vanopstal ever opted to take conflicts to court on behalf of principals (although they were themselves defendants in some court cases in their capacity as underwriters).Footnote 92 Instead, as we have seen, they tried to resolve disputes privately or, otherwise, through arbitration. Women and men in the Chamber created their own strategy for resolving conflicts, based on their needs and interests and, in the case of Jousse and Vanopstal, those of their principals.Footnote 93

Where some women were able to navigate the Parisian institutional landscape to their advantage, others found themselves in more precarious positions. On April 18, 1673, the admiralty court issued two default judgments against Hélissant and Henri Desanteul totaling 10,000 livres.Footnote 94 In the second order, pertaining to a vessel named the Orrore, the court noted it was simply enforcing a judgment made by the Chamber’s arbiters on January 20. François Moreau de Launay, acting as commission agent for prominent Malouin merchants, had been forced to pursue Hélissant and Desanteul in court for payment.

We should not assume Hélissant and Desanteul were playing the role of Savary’s unscrupulous underwriters. We have seen that Hélissant is unlikely to have suffered large losses from her portfolio in 1672: indeed, she made quite handsome profits across the period 1668 to 1672 (see Table 3). Nevertheless, the sudden influx of claims may have caught her off guard, especially if she had invested her premium income on receipt: delay tactics may have been necessary for her and Desanteul to draw on their credit resources to make payment. Such delays came at a price, however: the judgment for the Orrore specified that interest would be owed on the principal, to be calculated “from the day of the sentence in the Chamber” until the day the principal was ultimately paid.Footnote 95 If Hélissant and Desanteul had paid immediately, they would have been liable for almost three months of interest.

Yet they did not pay immediately. Instead, they submitted petitions to the admiralty court to appeal. The nature of both petitions was the same: they accused Moreau of failing in both cases to provide the “supporting documents” to justify the “claimed loss.”Footnote 96 Although there is no record of what followed this, it is clear Hélissant and Desanteul were willing to pursue every legal avenue in the hopes of being discharged from the policies they had signed. Thus, despite operating from a position of weakness, they still had options when faced with conflict and, like other women and men around them, leveraged these options in pursuit of their interests.

Conclusions: Gender and Marine Insurance

The year 1673 marked a high point in female agency in the Parisian insurance market under Louis XIV. The Chamber’s underwriting dramatically contracted thereafter, as underwriters and policyholders alike lost confidence in the market and the Chamber’s capacity to ensure members kept their commitments.Footnote 97 The institution plodded on somehow until 1686, when Colbert’s son, the marquis de Seignelay, dismantled it and established in its place what is possibly the first chartered company in the history of marine insurance, the Royal Insurance Company (Compagnie générale des assurances et grosses aventures).Footnote 98 The Company was endowed with a monopoly on marine insurance in Paris, preventing those outside the institution from underwriting without its express permission. Its shareholders—fixed at a maximum of thirty—were all men. When Charles Lebrun died in 1698, his widow, Marguerite Maurice, and his children inherited his share(s) in the Company.Footnote 99 Nevertheless, as Lebrun’s heir, Maurice was required by the Company’s articles of association to sell her late husband’s share(s) within a year and enjoyed no right to any dividends in the meantime. While shares could be sold on the open market—theoretically giving women the opportunity to join the institution—current shareholders had right of first refusal, ensuring the Company remained socially homogeneous.Footnote 100

Women also seem to have been excluded elsewhere in the Company’s activity. While the Company’s policy registers have been lost, preventing a direct comparison with the Chamber, two registers have survived for its insurance claims from 1686 to 1692, which give a valuable insight into the role of commission agents in facilitating the Company’s business. These registers offer no evidence a woman ever served as a commission agent. Meanwhile, from a total of 590 claims, only 28 featured female policyholders.Footnote 101 The Company thus reversed the Chamber’s success in bringing female capital into the Parisian insurance market and supporting the mercantile enterprises of women across France.

While the Chamber was short-lived, the institution nevertheless offers unique insights into female engagement at a crucial juncture in the development of the France’s Atlantic Empire. While the literature on female agency in commercial networks has flourished, far less has been said about female agency in formal commercial institutions. In the words of Sophie Jones and Siobhan Talbott, “the spaces of ‘doing’ commerce—including exchanges, counting houses, and coffee houses—were intrinsically masculine,” meaning sources often give little indication of how far (if at all) women participated in these spaces.Footnote 102 Underwriting spaces are more difficult for the historian to access than most: in keeping with Fernand Braudel’s “opaque” sphere of capitalism—where a small minority operated, beyond the comprehension of the rest of society—the complex (and, in the wrong circumstances, socially subversive) practices of marine insurance were among the most opaque for contemporaries, while leaving the faintest of traces on the historical record.Footnote 103 The Chamber brings a remarkable degree of transparency to this opaque business, demonstrating that women could and did participate in it.

Women may not have received the recognition of their male counterparts in the Chamber, but they were integral to the market as buyers, sellers, and intermediaries, leveraging their commercial knowledge and networks in service to their commercial activities. Chupin made sound underwriting decisions on behalf of her husband; Hélissant maintained an extensive portfolio spanning the Western Hemisphere; Jousse did the same, while also negotiating insurance policies and sea loans for an international clientele.

Furthermore, women in the Chamber were as capable as their male counterparts of crafting nuanced strategies for resolving conflicts. While Jousse and Carré proved willing to go before arbiters to resolve disputes (or, in Jousse’s case, even meet with underwriters informally to negotiate agreements), Lasson and Hélissant both drew on the support of the Parisian admiralty court, albeit from differing positions of strength. Thus, while women did not necessarily exercise the same agency as men in the Chamber’s arbitration chamber, the court system ensured women had multiple options for resolving conflicts.

In engaging so extensively in the market, the female underwriters of Paris demonstrate that the homosociality of Lloyd’s, while undoubtedly deep-rooted, was not inevitable. In a Bloomberg investigation from 2019, Gavin Finch suggests the culture of sexism in Lloyd’s has deep historical roots that can be traced back to the institution’s origins: indeed, Finch characterizes the unequal treatment of women in Lloyd’s as an “anachronism,” the manifestation of Lloyd’s “archaic” nature.Footnote 104 Similarly, Simon English has recently condemned the “culture” of Lloyd’s as “out of date.”Footnote 105 Yet the Royal Insurance Chamber reveals the capacity for female agency in marine insurance decades before Lloyd’s coffeehouse became a space for underwriting.

Furthermore, just as Lloyd’s was rising to supremacy in the eighteenth century, women were making significant investments in London’s chartered insurance companies.Footnote 106 As we have seen, this was part of a broader process of female investment in public institutions: by the middle of the eighteenth century, “between one fifth and one third of investors in joint-stock companies, the Bank of England, and the national debt were women.”Footnote 107 Indeed, just as women managed to engage in the Parisian capital market through institutions such as the Chamber and the city’s notarial offices, the most successful female investors and brokers in England proved adept at navigating spaces of finance, including coffeehouses, the Exchequer, East India House, and the Bank of England.Footnote 108 Far from being a logical by-product of the times, then, the apparent absence of female underwriters at Lloyd’s should be understood as an aberration.

In underwriting the French Atlantic Empire, thereby supporting Colbertian initiatives, Parisian women joined these Englishwomen in facilitating European colonial development. Misha Ewen finds that the Virginia Company sought (and secured) female investment in the early seventeenth century, shedding light on how “women facilitated the growth of a burgeoning English empire.”Footnote 109 Froide goes further, arguing that Englishwomen in the Financial Revolution were engaging in a form of “financial patriotism” that amalgamated self-interest and the good of the state.Footnote 110 Indeed, “without the money of thousands of Englishwomen, Britain’s trade, wars, and empire would not have been possible or as successful.”Footnote 111

We can see a similar alignment between self-interest and state interest in the case of the Chamber: women and men alike supported Colbertian ventures, colonial or otherwise, with Bellinzani acting as a node between the underwriters and the monarchy. The Northern, Levant, and West India Companies benefited from the underwriting of Jousse, Hélissant, and Lefebvre; moreover, Jousse underwrote the slaving voyage of the Saint Esprit, and Soyécourt invested directly in that of the Saint François. We know that female merchants in western African ports such as Cacheu participated in the sale of enslaved people into the Atlantic slave trade; women in Britain and North America also contributed to slaving activities, for example, through investing in the South Sea and Royal African Companies or outright slave ownership.Footnote 112 The cases here build on (and go beyond) this work by revealing how female credit and underwriting capital in Paris played a role in furthering France’s early slaving expeditions.

Zooming out, the underwriting portfolios of Hélissant, Jousse, and Lefebvre also helped to support French maritime activity at the outset of the Dutch War, just as protection was needed most. In particular, Newfoundland cod fishers and Greenland whalers secured extensive coverage in Paris, sustaining provincial economic activity in wartime while continuing to grow the pool of sailors on which Colbert depended to achieve his naval and commercial ambitions.

The Royal Insurance Chamber therefore emerges as the hitherto missing piece in the jigsaw of Colbertianism. While the Sun King’s gaze was fixed firmly on France’s eastern frontiers, Colbert sought to promote France’s commercial, industrial, and colonial interests in the Atlantic. Through the Chamber, Colbert was able to leverage Parisian capital in service to his multifaceted maritime and colonial policies. In the process, forgotten women like Hélissant and Jousse became underwriters of empire itself.

Acknowledgment

The research for this article was conducted thanks to funding from the European Research Council: ERC grant agreement no. 724544: AveTransRisk—Average–Transaction Costs and Risk Management during the First Globalization (Sixteenth–Eighteenth Centuries), as well as funding from the Economic History Society through a Postan Fellowship held at the Institute of Historical Research. I am grateful to Maria Fusaro and Jake Dyble for their comments on earlier drafts of this article, and to Sabine Go for her valuable recommendations in dealing with the peculiarities of my data. I am especially grateful to Ian Wellaway for his efforts in designing the AveTransRisk database based on my needs (and those of my colleagues on the AveTransRisk team) and working with me to facilitate data analysis. Finally, I am indebted to Julie Hardwick, Amy Froide, and a third anonymous peer reviewer, whose extraordinarily generous and thoughtful comments have improved this piece immeasurably. All errors remain my own.