Refine search

Actions for selected content:

22 results

A Meta-Analysis of Attitudes Towards Migrants and Displaced Persons

-

- Journal:

- British Journal of Political Science / Volume 55 / 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 24 November 2025, e168

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Stabilization interventions in the treatment of traumatized refugees: A scoping review

-

- Journal:

- Cambridge Prisms: Global Mental Health / Volume 12 / 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 23 June 2025, e73

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Displacement and Compensation in Germany after the First and Second World Wars

-

- Journal:

- Central European History / Volume 58 / Issue 3 / September 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 25 March 2025, pp. 293-313

- Print publication:

- September 2025

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

1 - Dar es Salaam

-

- Book:

- New Sudans

- Published online:

- 06 February 2025

- Print publication:

- 13 February 2025, pp 29-57

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Memory of Forced Displacements in the Discourse and Coping Strategies of Crimean Tatars in Post-2014 Crimea

-

- Journal:

- Nationalities Papers , FirstView

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 10 January 2025, pp. 1-17

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Child growth and refugee status: evidence from Syrian migrants in Turkey

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Demographic Economics / Volume 90 / Issue 3 / September 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 18 September 2024, pp. 486-520

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Chapter 19 - Arabic Diasporic Literary Trajectories

- from Part III - Readings in Genre, Gender, and Genealogies

-

-

- Book:

- Diaspora and Literary Studies

- Published online:

- 20 July 2023

- Print publication:

- 10 August 2023, pp 329-345

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Making an economic argument for investment in global mental health: The case of conflict-affected refugees and displaced people

-

- Journal:

- Cambridge Prisms: Global Mental Health / Volume 10 / 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 02 March 2023, e10

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Prevalence and prevention of suicidal ideation among asylum seekers in a high-risk urban post-displacement setting

-

- Journal:

- Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences / Volume 31 / 2022

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 17 October 2022, e76

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Climate-induced displacement in the Sahel: A question of classification

-

- Journal:

- International Review of the Red Cross / Volume 103 / Issue 918 / December 2021

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 21 February 2022, pp. 1029-1065

- Print publication:

- December 2021

-

- Article

- Export citation

Prevalence of complex post-traumatic stress disorder in refugees and asylum seekers: systematic review

-

- Journal:

- BJPsych Open / Volume 7 / Issue 6 / November 2021

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 15 October 2021, e194

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Forced Displacement and Asylum Policy in the Developing World

-

- Journal:

- International Organization / Volume 76 / Issue 2 / Spring 2022

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 31 August 2021, pp. 337-378

- Print publication:

- Spring 2022

-

- Article

- Export citation

Personal restoration and feelings of guilt with victims of forced displacement in the colombian caribbean

-

- Journal:

- European Psychiatry / Volume 64 / Issue S1 / April 2021

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 13 August 2021, p. S724

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- Export citation

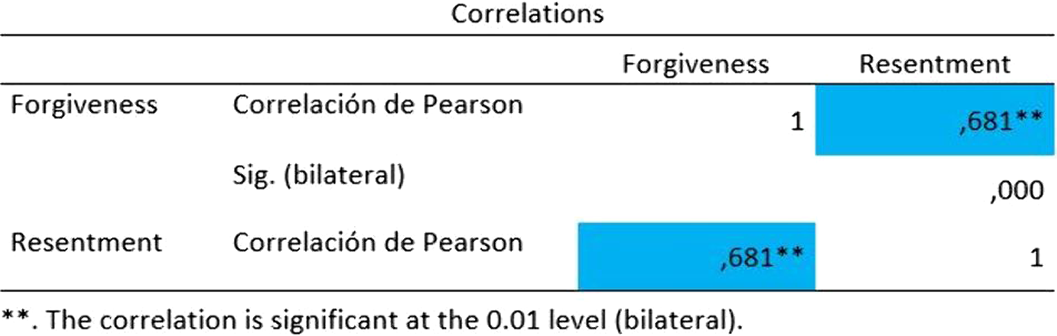

Resentment and forgiveness with victims of forced displacement in three cities of colombia

-

- Journal:

- European Psychiatry / Volume 64 / Issue S1 / April 2021

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 13 August 2021, p. S392

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- Export citation

4 - The Actors, Acts and Victims of State Violence

- from Part I - Historical Background

-

- Book:

- Limits of Supranational Justice

- Published online:

- 30 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 12 November 2020, pp 133-182

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

The Curse of Displacement: Local Narratives of Forced Expulsion and the Appropriation of Abandoned Property in Abkhazia

-

- Journal:

- Nationalities Papers / Volume 49 / Issue 4 / July 2021

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 15 June 2020, pp. 710-727

-

- Article

- Export citation

Ambivalent Relationships: The Portuguese State and the Indian Nationals in Mozambique in the Aftermath of the Goa Crisis, 1961–1971

-

- Journal:

- Itinerario / Volume 44 / Issue 1 / April 2020

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 24 March 2020, pp. 106-139

-

- Article

- Export citation

Hypocritical Inhospitality: The Global Refugee Crisis in the Light of History

-

- Journal:

- Ethics & International Affairs / Volume 34 / Issue 1 / Spring 2020

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 24 March 2020, pp. 3-12

-

- Article

- Export citation

Remedying Displacement in Frozen Conflicts: Lessons From the Case of Cyprus

-

- Journal:

- Cambridge Yearbook of European Legal Studies / Volume 18 / December 2016

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 15 July 2016, pp. 152-175

-

- Article

- Export citation

The impact of forced displacement in World War II on mental health disorders and health-related quality of life in late life – a German population-based study

-

- Journal:

- International Psychogeriatrics / Volume 25 / Issue 2 / February 2013

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 24 September 2012, pp. 310-319

-

- Article

- Export citation