6 results

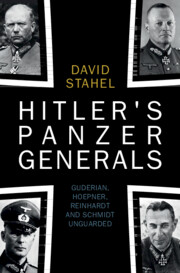

Hitler's Panzer Generals

- Guderian, Hoepner, Reinhardt and Schmidt Unguarded

-

- Published online:

- 04 May 2023

- Print publication:

- 04 May 2023

2 - The Private Generals

-

- Book:

- Hitler's Panzer Generals

- Published online:

- 04 May 2023

- Print publication:

- 04 May 2023, pp 22-74

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - The Letters of the Panzer Generals

-

- Book:

- Hitler's Panzer Generals

- Published online:

- 04 May 2023

- Print publication:

- 04 May 2023, pp 10-21

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

4 - The Criminal Generals

-

- Book:

- Hitler's Panzer Generals

- Published online:

- 04 May 2023

- Print publication:

- 04 May 2023, pp 133-182

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - The Public Generals

-

- Book:

- Hitler's Panzer Generals

- Published online:

- 04 May 2023

- Print publication:

- 04 May 2023, pp 75-132

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - The Military Generals

-

- Book:

- Hitler's Panzer Generals

- Published online:

- 04 May 2023

- Print publication:

- 04 May 2023, pp 183-238

-

- Chapter

- Export citation