7 results

4 - Post-miracle

-

- Book:

- Why the Ancient Greeks Matter

- Published online:

- 06 February 2025

- Print publication:

- 06 February 2025, pp 151-170

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

15 - LBJ, the Great Society, and Vietnam

- from Part II - Homefronts

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge History of the Vietnam War

- Published online:

- 02 January 2025

- Print publication:

- 28 November 2024, pp 321-342

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - Incarceration and Confinement Literature

- from Part II - African American Genres

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to Contemporary African American Literature

- Published online:

- 14 December 2023

- Print publication:

- 21 December 2023, pp 128-146

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

10 - Social Justice and the American Essay

- from Part II - Voicing the American Experiment (1865–1945)

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge History of the American Essay

- Published online:

- 28 March 2024

- Print publication:

- 14 December 2023, pp 166-181

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

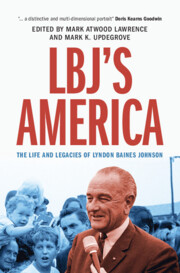

LBJ's America

- The Life and Legacies of Lyndon Baines Johnson

-

- Published online:

- 19 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 19 October 2023

Chapter 4 - The Great Society and the Beloved Community: Lyndon Johnson, Martin Luther King Jr., and the Partnership That Transformed a Nation

-

-

- Book:

- LBJ's America

- Published online:

- 19 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 19 October 2023, pp 94-119

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - The Skepticism toward Moderation and What Its Critics Miss about It

- from PART II - WHAT KIND OF VIRTUE IS MODERATION?

-

- Book:

- Why Not Moderation?

- Published online:

- 12 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 12 October 2023, pp 37-45

-

- Chapter

- Export citation