4 results

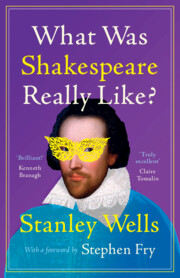

What Was Shakespeare Really Like?

-

- Published online:

- 14 September 2023

- Print publication:

- 14 September 2023

3 - What Do the Sonnets Tell Us about Their Author?

-

- Book:

- What Was Shakespeare Really Like?

- Published online:

- 14 September 2023

- Print publication:

- 14 September 2023, pp 63-88

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 1 - Allegories of Love

- from Part I - Ars memoriae, ars amatoria

-

-

- Book:

- Memory and Affect in Shakespeare's England

- Published online:

- 07 June 2023

- Print publication:

- 27 July 2023, pp 25-43

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction

-

- Book:

- The Afterlife of Shakespeare's Sonnets

- Published online:

- 16 August 2019

- Print publication:

- 29 August 2019, pp 1-11

-

- Chapter

- Export citation