5 results

8 - Remaking Spaces and Societies

- from Part II - Themes in the Making of Hegemony

-

- Book:

- Religion and the Making of Roman Africa

- Published online:

- 24 October 2024

- Print publication:

- 07 November 2024, pp 320-383

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - Making Offerings

- from Part II - Themes in the Making of Hegemony

-

- Book:

- Religion and the Making of Roman Africa

- Published online:

- 24 October 2024

- Print publication:

- 07 November 2024, pp 270-319

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

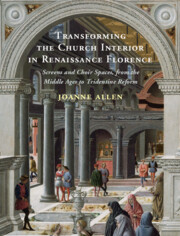

Transforming the Church Interior in Renaissance Florence

- Screens and Choir Spaces, from the Middle Ages to Tridentine Reform

-

- Published online:

- 30 April 2022

- Print publication:

- 05 May 2022

2 - Altars and Christian Precedence in the Holy Places

-

- Book:

- The Holy Land and the Early Modern Reinvention of Catholicism

- Published online:

- 30 April 2021

- Print publication:

- 20 May 2021, pp 68-120

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - The Altars of the Lares Augusti

-

-

- Book:

- The Social Dynamics of Roman Imperial Imagery

- Published online:

- 09 November 2020

- Print publication:

- 12 November 2020, pp 25-51

-

- Chapter

- Export citation