6.1 Introduction

In December 2019, a Supreme Court ruling in the Netherlands made headlines worldwide.Footnote 1 In Urgenda Foundation v State of the Netherlands, the highest national court confirmed the previous lower instance rulings, obligating for the first time a State to reduce general emissions in line with international commitments. The Dutch Supreme Court found that the State’s inaction on climate change violated its citizens’ rights to life and privacy under Articles 2 and 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), respectively, and ordered the State to cut its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by at least 25 per cent by 2020, compared to levels in 1990. By May 2022, over seventy cases worldwide had been filed to challenge the implementation or ambition of climate targets and policies affecting the whole of a country’s economy and society.Footnote 2

In such cases, the plaintiffs have a political purpose: they seek societal change, typically (but not necessarily) more ambitious climate protection. Governments are often the defendants in such cases, which increases the political significance of the litigation.Footnote 3 Sometimes national legislation is challenged.Footnote 4 The relationship between the three branches and hence the idea of separation of powers lies at the core of the debate about strategic climate litigation. While some cases have been dismissed and described as a ‘direct attack on the separation of powers’,Footnote 5 many cases have been upheld, with apex courts issuing decisions that are favourable for climate action. This chapter discusses the relevance of separation of powers in a wide array of climate cases including in terms of the outcome of successful and unsuccessful cases. The purpose is to identify emerging best practice from the case law to date.

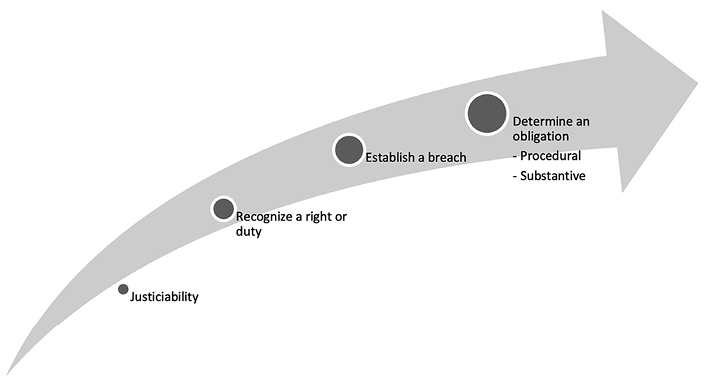

Building on the definitions and methods in Section 6.2, we ask: ‘In climate litigation cases where separation of powers concerns arise, how do courts engage with that matter?’ Our overview of case law development in Section 6.3 suggests that separation of powers concerns arise at four stages in the adjudicatory process: justiciability; recognising a right or duty; establishing a breach; and determining a specific obligation, respectively. In cases that result in a legally enforceable obligation, furthermore, separation of powers concerns may relate to whether the obligation is procedural or substantive. In some of these cases, courts innovatively provided procedural obligations for a breach of substantive duties. In Section 6.4, we consider conditions for best practice. A central element of emerging best practice is that courts provide arguments for the rightfulness of enforcing the limits that the law imposes on the other branches. This includes prominent international norms, including open-textured and, at times, non-binding ones, and human rights norms. Another relevant (and replicable) element is that courts develop legally enforceable standards interpreting open-textured norms in light of best available science, usually found in the reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Lastly, we discuss the conditions for replicability (Section 6.5) of climate rulings across jurisdictions.

6.2 DEFINITIONS and Methods

Separation of powers is considered ‘the litmus test of legal and political legitimacy’ in constitutional democracies.Footnote 6 Yet, there is no one legal or conceptual blueprint of separation of powers. It is concretised in very different ways in different legal orders. In climate litigation, it is precisely a core issue of separation of powers that arises most, namely the boundaries of judicial powers.

The concept of separation of powers applies to the relationships between the legislative, executive, and judicial branches of government, sometimes referred to as the trias politica. In this chapter, we focus on the relationship of the judiciary to the other branches. We make sense of separation of powers by distinguishing between the concept and different conceptions.Footnote 7 We take a concept to convey a singular meaning or purpose, whereas different conceptions are different views on what it takes to achieve that purpose. The concept of separation of powers describes a constitutional arrangement of branches of government that avoids the concentration of power. However, jurisdictions apply the concept (realise the purpose) of separation of powers differently, resulting in distinct conceptions of separation of powers.

A functional conception of separation of powers entails that the different branches exercise different functions. According to this idea, law-making is the responsibility of parliaments and the execution of laws the responsibility of governments, while courts apply the laws. This account grants the legislature ‘an initiating place on the assembly line of law-making/law enforcement’ and is associated with ‘a principle of legislative supremacy’.Footnote 8 This conception relies heavily on the possibility to hold political representatives accountable for their decisions through regular elections. When defendants in climate litigation point to the ideal of separation of powers, this is often the conception they have in mind. Yet, at times, this conception may also figure in support of judicial intervention in climate litigation.

A relational conception, by contrast, entails that functions are shared between the different branches. This conception explicitly ‘aims to ensure that the tension between law and majoritarian politics is perpetuated and that neither law nor politics dominates the other’ over an extended period of time.Footnote 9 It characteristically relies on the capacities of the judiciary to control the exercise of powers by the other branches of government through judicial review. This conception typically appears in support of judicial intervention in climate litigation.

We treat the two conceptions just discussed as theoretical ‘ideal types’, which we do not expect to be observed in pure form.Footnote 10 A strictly functional conception of the separation of powers would exclude that the judicial branch ever exercises the powers of another branch; yet, it is accepted that judicial interpretation may also create law. A maximally relational construction would entail that the judicial branch may enjoy as much political power as the legislative and executive branches. Yet, even the most relational system among existing jurisdictions affirms basic functional separation. On our account, any legal system could be placed on a scale between a strictly functional enactment of separation of powers to a maximally relational construction.Footnote 11 Examples of jurisdictions that tend more toward the functional conception are France, the Netherlands, and Sweden. Examples of more relational jurisdictions include Germany and the United States.

Such a scale can be used for different methodological purposes in a study on climate litigation. When a court exerts less power over climate policy in a single case, we take it to express a more functional conception; when a court exerts more power over climate policy in a single case, we take it to express a more relational conception. As mentioned, this does not exclude that a functional conception is used to justify ruling in favour of full-on enforceable substantive obligation. A prime example is the Urgenda case.Footnote 12

To assess how courts handle separation of powers concerns in climate litigation, we have used the dataset of climate litigation cases compiled for this Handbook as the point of departure. We focus on cases where the issue of separation of powers has been reported as salient.

6.3 Case Law Development – State of Affairs

The categorisation of adjudicatory stages is divided into four levels and identifies two subcategories of obligations (see Figure 6.1). As any categorisation, it is subjective to an extent. In individual cases, courts may consider separation of powers at one or several of these adjudicatory stages.

Figure 6.1 The four levels and two subcategories of obligations making up the adjudicatory stages where separation of powers concerns arise

6.3.1 Justiciability

When courts consider whether a climate case is justiciable, separation of powers is the single most decisive underlying principle. Many procedural rules serve the purpose of protecting each branch’s core constitutional powers, that is, separation of powers. One could think of standing, availability of legal instruments to require governmental action, or time limits. This subsection considers the judicial reasoning, first, in cases that were found non-justiciable, and second, in cases in which justiciability was the focus of the judicial reasoning and that were found justiciable.

On a more abstract level, judges may be concerned that rulings in strategic climate litigation aiming at mitigation measures could interfere with the core task of elected politicians to prescribe general public policy choices.Footnote 13 According to a strict functional view of what separation of powers requires, judges may consider that they cannot decide that general policy choices are necessary and find the case non-justiciable. At the same time, the far-reaching interferences of the climate crisis with the enjoyment of human rights in a concrete and identifiable manner, not just in the future but also in the present, have become apparent. These interferences highlight the failure of the executive and the legislature to take measures that could be seen as adequate in light of established science.Footnote 14 Under a more relational conception of separation of powers, it is the task of the judiciary to prompt the other branches to carry out their constitutional mandates when they fail to do so.

Furthermore, even non-justiciable cases may have considerable political influence and contribute to the development of legal doctrine. Often, cases are found inadmissible on procedural grounds that serve the purpose of separation of powers but do not necessarily relate to whether judges could generally review climate policy. An example is standing requirements.Footnote 15 Our materials reveal that considerations of courts, which ultimately result in dismissals, may also include legal interpretations and doctrinal reasons that may lay the ground for more far-reaching climate policy. In light of the fact that the judiciary has a constitutional duty to ‘deliver justice’,Footnote 16 the logical minimum of reaction, when a case is brought, is declaring a case non-justiciable on specified grounds.

Juliana v United States is an example of a non-justiciable case from the United States.Footnote 17 In this case, a group of child plaintiffs alleged that several United States agencies had continued policies allowing for exploitation of fossil fuels, despite knowing of the hazards for more than fifty years. The plaintiffs claimed that the government thereby violated their constitutional rights, including a right to due process under the Fifth Amendment to a ‘climate system capable of sustaining human life’. The Ninth Circuit concluded in a 2-1 decision ‘reluctantly’ that the plaintiffs’ ‘impressive case for redress must be represented to the political branches of government, not the judiciary’.Footnote 18 In justifying the outcome, the court sided with a more functional conception of separation of powers.

Outside the United States, justiciability has been the focus of climate cases in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and Pakistan.Footnote 19 Similarly, in the supporting judicial reasoning one can pinpoint elements of a more functional conception of separation of powers. In Sharma and Others v Minister for the Environment, eight young people, claiming to represent all people under 18, filed a putative class action in Australia’s Federal Court to block a coal project. They asserted that it would exacerbate climate change and harm young people in the future. The Federal Court of Australia established a new duty of care to avoid causing personal harm to children but declined to issue an injunction to force the minister to block the coal mine extension. The judge rejected the minister’s argument as to why alleged ‘policy reasons’ ought to have prevented the recognition of the duty of care. Contrary to the minister’s claims, the judge stated that the recognition of this duty would not interfere with the minister’s statutory task, nor necessarily render tortious any activity generating GHGs. Despite the Federal Court’s decision, the minister granted approval for the proposed mine expansion, and in March 2022 the Full Federal Court of Australia unanimously overturned the primary judge’s decision to impose a duty of care on the minister. The three judges had separate reasonings. Chief Justice Allsop found that the duty would require consideration of questions of policy ‘unsuitable for the judicial branch to resolve’.Footnote 20

By contrast, the Superior Court of Ontario in Canada found in Mathur et al v Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Ontario (preliminary decision) that ‘[t]he fact that the matter is complex, contentious or laden with social values does not mean that the courts can abdicate the responsibility vested in them by our Constitution to review legislation for Charter compliance when citizens challenge it. In such circumstances, it is the court’s obligation to decide the matter’.Footnote 21 This case emphasises the functional argument that it is the judiciary’s mandate and duty to apply constitutional law.

Equally grappling with issues of justiciability, Justice Mallon argued for the High Court of New Zealand in the case of Sarah Thomson v The Minister for Climate Change Issues that:

The courts have recognised the significance of the issue for the planet and its inhabitants and that those within the court’s jurisdiction are necessarily amongst all who are affected by inadequate efforts to respond to climate change. The various domestic courts have held they have a proper role to play in Government decision making on this topic, while emphasising that there are constitutional limits in how far that role may extend. The IPCC reports provide a factual basis on which decisions can be made. Remedies are fashioned to ensure appropriate action is taken while leaving the policy choices about the content of that action to the appropriate state body.Footnote 22

In its reasoning, the Court relied on a relational conception of separation of powers while stressing the importance of functional considerations. It reasoned more specifically that the ‘importance of the matter [climate change] for all and each of us warrants some scrutiny of the public power in addition to accountability through Parliament and the General Elections’, yet noted that there are ‘constitutional limits’ to the role of the judiciary, and that, if a ground of review ‘requires the Court to weigh public policies that are more appropriately weighed by those elected by the community’, it may be necessary for the Court to ‘defer to the elected officials’.Footnote 23

In the case of Michael John Smith v Fonterra Co-Operative Group Limited and Ors, the respondent companies are some of New Zealand’s largest GHG emitters (including from the dairy and meat industry).Footnote 24 In this case the issue was whether tort law could be used to seek wide-ranging private law remedies with respect to climate change. According to one cause of action, the defendants allegedly had a duty to cease contributing to climate change. The High Court found that there were ‘significant hurdles’ for Smith in persuading the Court that this new duty should be recognised but determined that the relevant issues should be explored at a trial.Footnote 25 Invoking a more functional conception of separation of powers, the High Court ultimately decided against any regulation of policy content. It argued that ‘[t]he Courts are poorly equipped to deal with the issues which Mr. Smith seeks to raise. This country’s response to climate change involves policy formation, value judgments, risk analysis, trade-offs and distributional outcomes. These matters are well outside the normal realms of civil litigation’.Footnote 26 It further explained that ‘[i]f the Courts were to reach different conclusions than Parliament, there could be inconsistent and different net zero emission targets and different ways of dealing with the problems thrown up by climate change. That would be highly undesirable and would put significant emitters in a quandary’.Footnote 27

6.3.2 Recognise a Right or Duty

Separation of powers concerns remain equally present after judges have found a case justiciable and recognise a legal right or duty – positive or negative.Footnote 28 Recognising a legal right or duty is an important step in the judicial process including in those cases that determine a particular obligation, with notable examples being Urgenda, VZW Klimaatzaak v Kingdom of Belgium and Others, Future Generations v Ministry of the Environment and Others, Neubauer and Others v Germany, Notre Affaire à Tous and Others v France, and Shrestha v Office of the Prime Minister and Others.Footnote 29 However, a court may also stop at this level of identifying rights or duties of the parties, for example if it does not establish a breach. These rulings may have a symbolic value in political discourse or obligate the executive or legislative branches to take these rights or duties into consideration.

An example of a case with high constitutional and symbolic value is Neubauer.Footnote 30 In this case, the German Federal Constitutional Court recognised that the German State had a constitutional duty to address the harm posed by climate change in order to protect the constitutional rights to life and health, protected under the German Constitution and the ECHR, ‘by taking steps which […] contribute to stopping human-induced global warming and limiting the ensuing climate change’.Footnote 31

Urgenda confirmed in three different instances that climate change fell within the scope of protection of the rights to life and to private and family life, under Articles 2 and 8 ECHR.Footnote 32 It also confirmed that the State is subject to a duty of care in tort, which is interpreted in light of these human rights provisions. While the District Court reasoned that the State’s duty of care in tort, as an open-textured norm, must be interpreted in a manner that is, so far as this is possible, consistent with its obligations under international law.Footnote 33 The Dutch government appealed the decision, and Urgenda filed a cross-appeal with respect to the ECHR claim. In late 2018, the Court of Appeal upheld the decision of the District Court, while permitting Urgenda to make a claim under the ECHR. The Dutch government appealed to the Dutch Supreme Court, which affirmed in December 2019 the order of the District Court and the Court of Appeal’s admission of Urgenda’s claim under the ECHR. The Supreme Court interpreted the Netherlands’ obligations under Articles 2 and 8 ECHR by drawing on non-binding commitments of the Dutch State under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), soft law sources such as Conference of the Parties’ (COP) decisions, and ‘scientific insights and generally accepted standards’.Footnote 34

Building on Urgenda, the case of Milieudefensie et al v Royal Dutch Shell plc extends the duty of care under tort law (Article 6:162 of the Dutch Civil Code informed by Articles 2 and 8 ECHR) to private companies.Footnote 35 The District Court accepted that given the Paris Agreement’s goals and the scientific evidence regarding the dangers of climate change, Shell has a duty of care to take action to reduce its GHG emissions.

6.3.3 Establish a Breach

The next stage at which separation of powers concerns arise is when courts consider whether they recognise a breach, even if that does not necessarily imply that the court orders the defendant to take action. Again, even if such rulings may not prescribe a specific enforceable obligation, they may have high symbolic value in the political discourse and establish important and potentially replicable interpretations of the law.

In VZW Klimaatzaak, the Brussels Court of First Instance found a duty and a breach of that duty, but did not establish an enforceable obligation. The Court found the federal state and the three regions jointly and individually in breach of their duties of care for failing to enact good climate governance. However, the Court declined to issue an injunction ordering the government to set the specific emission reduction targets requested by the plaintiffs. The Court found that the separation of powers doctrine limited the Court’s ability to set such targets and that doing so would contravene legislative or administrative authority. On appeal, this aspect of the decision was overturned – with the Court of Appeal issuing an order requiring the federal state and regions to adhere to a more ambitious 2030 mitigation target.Footnote 36

There are various other examples where separation of powers has not proven to be a barrier in establishing duty and breach. In the Future Generations case, the Supreme Court of Colombia found that the State’s failure to prevent deforestation, which exacerbates climate change, violated the claimants’ constitutional rights of life, health, and minimum subsistence: ‘It is clear that despite several international commitments, legislation, and jurisprudence on the subject, the Colombian State has not efficiently tackled the problem of deforestation in the Amazon’.Footnote 37

An example from Nepal is the Shrestha case.Footnote 38 In this case, the Supreme Court of Nepal determined that the State’s failure to adopt a comprehensive law on climate change and to adequately address the existing impacts of climate change violated the right to life and to live with dignity, as well as the right to a healthy environment under the Nepalese Constitution.Footnote 39

In Neubauer, the German Federal Constitutional Court found that the duty to take ‘measures that help to limit anthropogenic global warming and the associated climate change’ applies despite ‘[t]he fact that the German State is incapable of halting climate change on its own’.Footnote 40 The Court found that this requires the legislature to adopt legislation to reduce GHG emissions in a ‘sufficiently prudent manner’, without ‘offload[ing] reduction burdens onto the future’.Footnote 41 The Court established a breach of the rights protected under the German Constitution.Footnote 42

The Municipal Court of Prague found in the first instance in the Klimatická žaloba case that the ‘far-reaching effects’ of climate change posed a threat to the right to a favourable environment, which is protected under the constitution.Footnote 43 The constitutional duty to protect human rights thus required the government to develop specific and comprehensive mitigation measures ‘without undue delay’.Footnote 44 The court found that the government was not doing enough to adequately reduce emissions before 2030, and thus violated its duty to protect human rights. It concluded that ‘[t]he defendants’ failure to act deprived the applicants of their right to a favourable environment’.Footnote 45

In Pakistan, the High Court of Lahore held in Leghari v Federation of Pakistan that the State’s failure to address the impacts of climate change within the country violated the plaintiff’s right to life as well as the right to a healthy environment (among other rights).Footnote 46 In this case, Ashgar Leghari, a Pakistani farmer, argued that the government had failed to meet its climate change mitigation and adaptation targets, which had resulted in immediate impacts on the water, food, and energy security of Pakistan in a way that interfered with his fundamental right to life. The Court ruled in response that ‘the delay and lethargy of the State in implementing the Framework offends the fundamental rights of the citizens which need to be safeguarded’.Footnote 47 When establishing the breach, the Court argued that fundamental rights must be guided by the constitutional values of democracy, equality, and social, economic, and political justice, as well as the international environmental principles of sustainable development, the precautionary principle, intergenerational and intragenerational equity, and the doctrine of public trust.

Equally, in Urgenda, the first successful strategic climate case aimed at general emission reduction, the Dutch Supreme Court concluded that Dutch climate mitigation efforts were not consistent with IPCC science and the government thus violated its obligation to protect under Articles 2 and 8 of the ECHR.Footnote 48

6.3.4 Determine an Enforceable Obligation

Finally, a court may impose an enforceable obligation on the parties to the case. These enforceable obligations may be procedural or substantive.Footnote 49 From a separation of powers perspective, determining procedural obligations may prima facie be seen as less controversial than determining substantive ones. The principled reasoning of the Supreme Court in Nature and Youth Norway and others v Norway may serve as an illustration. The case concerned the validity of a royal decree of 2016 to grant ten petroleum explorations licences in the southern and south-eastern parts of the Barents Sea. The Court did not rule in favour of the plaintiffs but provided extensive reflections in relation to separation of powers. It held that ‘decisions involving basic environmental issues often require a political balancing of interests and broader priorities’.Footnote 50 Therefore, the Court stated, ‘[d]emocracy considerations […] suggest that such decisions should be taken by popularly elected bodies, and not by the courts’.Footnote 51 Yet, the Court also noted that democratic considerations have less bearing in regard to procedural duties, noting specifically that ‘restraint is less required when it comes to assessing the procedure’ as ‘in reviewing the political balancing of interests’.Footnote 52

We treat procedural and substantive obligations in separate subsections later on. We should add, however, that the dividing line between procedural and substantive obligations is at times difficult to draw. A case in point is Neubauer, which primarily established procedural obligations but also determined that the German Constitution entails a substantive constitutional obligation to establish a law with a zero-emission target for 2050. Similarly, in Friends of the Irish Environment CLG v The Government of Ireland, Ireland and The Attorney General, the Supreme Court of Ireland ordered the Irish government to return to the drawing board and develop a new National Mitigation Plan, which is a procedural obligation aiming for a substantive outcome.Footnote 53

6.3.4.1 Procedural Obligations

Procedural obligations concern processes for governing climate policy without directly regulating the content of such policy. While these rulings do not intervene substantively in the decisions of the political branches, procedural remedies may still have an impact on climate policy as imposed institutional structures change the conditions for policy-making.

For example, in Save Lamu et al v National Environmental Management Authority and Amu Power Co Ltd, a community-based organisation representing Lamu County and other individual claimants challenged the issuance of a licence by the Kenyan National Environmental Management Authority (NEMA) to a power company for the construction of the first coal-fired power plant in Kenya.Footnote 54 The claimants argued that the Kenyan NEMA failed to conduct a proper Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) and therefore contributed to the adverse effects on human health and biodiversity caused by climate change. The Tribunal set aside the licence issuance and decided that the Kenyan NEMA had violated the EIA regulations by granting it without proper and meaningful public participation in the process. It stated that ‘the judicial function of the Tribunal is to examine whether there was compliance with statute. In the present appeal, the procedure was not followed and the process was seriously flawed’.Footnote 55

Similarly, Neubauer established a procedural obligation requiring the legislature to return to the drawing board and adopt national legislation in line with constitutionally protected human rights, including for the future, that is, the period after 2030. Neubauer did not articulate a particular substantive reduction obligation. Arguably, the latter reflects a degree of judicial self-restraint that relates to the German Federal Constitutional Court’s self-conception of the role of the judiciary in relation to the other branches. The Court expresses this when emphasising that it is for the legislature to specify the (substantive) emission reduction objectives within what is legal in light of the requirement of climate protection under Article 20(a) GG.Footnote 56 The Neubauer case is recurrent in our later discussions on emerging best practice and replicability.

6.3.4.2 Substantive Obligations

All else being equal, rulings determining substantive obligations usually remain more controversial from a separation of powers perspective. Still, some courts proceed to such measures. Such cases exist from Ireland, the Netherlands, France, and Colombia.Footnote 57 Among these, only the Irish case relied on existing parliamentary legislation.

In Friends of the Irish Environment CLG, the separation of powers was a key issue. As in the Neubauer case, the distinction between a procedural and substantive obligation can be difficult to draw, as the final ruling required a more specific National Mitigation Plan. The High Court ruled against the plaintiffs, holding, inter alia, that the State must be given a broad margin of discretion in determining its climate policies, with reference to the separation of powers and the nature, extent, and wording of the statutory obligations in play.Footnote 58 In comparison to the High Court, the conception of separation of powers upheld by the Supreme Court can be seen as more relational, as it concluded that ‘the issues are justiciable and do not amount to an impermissible impingement by the courts into areas of policy’.Footnote 59 Yet, functional separation remained important, as the obligation established by the Court ultimately relied on national legislation, namely the 2015 Climate Action and Low Carbon Development Act.

Urgenda, which drew on Articles 2 and 8 of the ECHR, constitutes a different example of where courts imposed a specific substantive obligation (25% emission reduction). In the Urgenda case, the Court insisted that there remained a legitimate role for the judiciary in determining ‘whether the measures taken by the State are too little in view of what is clearly the lower limit of its share in the measures to be taken worldwide against dangerous climate change’.Footnote 60 The Court concluded its judgment by outlining why the order made was appropriate in light of the separation of powers, contrary to the State’s argument that the order constituted an impermissible ‘order to create legislation’.Footnote 61 The Urgenda case also recurs in our later discussions on emerging best practice and replicability.

The level of detail in imposing enforceable obligations on the State seems crucial. Courts appear willing to impose even substantive obligations but reserve the details of implementation to the State. This is in line with separation of powers considerations that reserve the making of general policy to the legislature. Examples that illustrate this emerging trend of climate rulings imposing general substantive obligations that reserve further (implementation) details to the policy-maker are Urgenda and Notre Affaire a Tous. In the latter case, the Administrative Court explicitly acknowledged that the government must be granted a wide margin of discretion when implementing a court order pertaining to GHG emissions targets, while this margin of discretion does not as such prevent the judiciary from ordering the government to adopt stronger climate mitigation measures:

In the circumstances of this case, it is appropriate to order the Prime Minister and the competent ministers to take all the necessary sectoral measures to compensate for the damage up to the uncompensated share of greenhouse gas emissions under the first carbon budget […]. It is appropriate, as has been said, to order the enactment of such measures within a sufficiently short period of time in order to prevent any worsening of that damage. In the context of the present case, the specific measures to make reparation for the damage may take various forms and consequently express choices which are within the Government’s discretion.Footnote 62

6.4 Emerging Best Practice

Separation of powers has been a central issue in the relatively short but dynamic lifespan of climate litigation. To a certain extent, identifying specific best practices around separation of powers is rendered difficult by the wide range of rules and principles that protect or interact with separation of powers very differently in various legal orders. In all climate litigation, the domestic legal order frames the role of the judiciary and determines what judges can and should do. Nevertheless, emerging best practices regarding the separation of powers can be identified with respect to several issues.

6.4.1 Role of the Judiciary in Applying the Law

The first emerging best practice results from how judges understand their own role vis-à-vis the other branches of government and provide arguments for this understanding. Several courts have emphasised that it is the role of the judiciary to apply the law. In other words, when the legislature has adopted a national law this mandates the judiciary to ensure that the legally binding commitments made under that national law are given effect.Footnote 63 They also generally emphasised the necessity of judicial review of executive conduct with respect to climate change legislation.Footnote 64 This exercise of judicial review renders matters which once might have been reserved to ‘politics’ a matter of lawful conduct.

DG Khan Cement Company v Government of Punjab is illustrative of this practice. In that case, the Supreme Court of Pakistan found that the judiciary is not only able but actually required to adjudicate cases that can help address the dangerous consequences of climate change.Footnote 65 The Court argued that ‘[t]his Court and the Courts around the globe have a role to play in reducing the effects of climate change for our generation and for the generations to come. Through our pen and jurisprudential fiat, we need to decolonize our future generations from the wrath of climate change, by upholding climate justice at all times’.Footnote 66

In Germany, which has a constitutional court that enjoys strong review powers over general laws and exceptionally high public support, including in politics and academia, the judiciary is formally in a position to directly restrain politics (legal constitutionalism). In the Neubauer case, a group of youth filed a legal challenge against the Federal Climate Protection Act arguing that the target of reducing GHGs 55 per cent by 2030 from 1990 levels was insufficient. The German Federal Constitutional Court struck down parts of that Act, which is a general federal law, as incompatible with fundamental rights protected under the German Constitution.

For its reasoning, the Court could rely on constitutional provisions that limit the scope for political decision-making to take measures to protect the environment or not. The Court found that Article 20a of the German Constitution obliges the legislature to protect the climate and aim towards achieving climate neutrality. Further, the Court stated that Article 20a ‘is a justiciable legal norm that is intended to bind the political process in favour of ecological concerns, also with a view to the future generations that are particularly affected’. Accepting arguments that the legislature must follow a carbon budget approach to limit warming to well below 2°C, and, if possible, to 1.5°C, the Court found that the legislature had not proportionally distributed the budget between current and future generations. Because ‘one generation must not be allowed to consume large parts of the CO2 budget under a comparatively mild reduction burden if this would at the same time leave future generations with a radical reduction burden and expose their lives to serious losses of freedom’, the Court ordered the legislature to set clear provisions for reduction targets from 2031 onward by the end of 2022.Footnote 67

An example from Canada is Mathur et al. Although judicial review is relatively weak in Canada, the Superior Court of Ontario explained that the Constitution ‘requires’ the Court to decide a climate case, even if ‘the matter is complex, contentious and laden with social values’.Footnote 68

In the Netherlands, by contrast with Germany and more like Canada, the judiciary is in a comparatively weak position vis-à-vis the political branches and may not review general laws in light of national constitutional rules or principles. However, this did not stop the courts in three instances (District Court, Court of Appeals, and Supreme Court) from ruling in favour of Urgenda, determining that, by failing to reduce GHG emissions by at least 25 per cent by end-2020, the Dutch government was acting unlawfully in contravention of its duty of care. In the higher two instances, the courts relied on Articles 2 and 8 of the ECHR, which enjoy constitutional status and direct enforceability in the Dutch system. Directly addressing the matter of separation of powers, the Dutch Supreme Court concluded

[D]ecision-making on the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions is a power of the government and parliament. They have a large degree of discretion to make the political considerations that are necessary in this regard. It is up to the courts to decide whether, in availing themselves of this discretion, the government and parliament have remained within the limits of the law by which they are bound.Footnote 69

In respect of a functional separation of powers, the Dutch Supreme Court insisted that it was a legitimate function of the judiciary, as required by the rule of law, to determine whether the State was complying with its legal obligations, and had ‘remained within the limits of the law by which they are bound’.Footnote 70 The Court argued further that ‘this order does not amount to an order to take specific legislative measures, but leaves the State free to choose the measures to be taken in order to achieve a 25% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2020’.Footnote 71

Notably, this was the first decision by any court ordering a State to limit GHG emissions for reasons other than statutory mandates. The Court pointed to ‘the severity of the consequences of climate change and the great risk of climate change occurring’.Footnote 72 The functional separation of powers arguments put forth by the defendant against justiciability, for example, were rejected ‘also because the State violates human rights’.Footnote 73

6.4.2 Giving Effect to International Norms

Judges have regularly relied on international law to substantiate their reasoning, either because no national climate legislation existedFootnote 74 or because international law further strengthened the case as it illustrated the objectives for which the national climate legislation had been adopted.Footnote 75

France is an illustrative example of a jurisdiction in which several courts have emphasised the relevance of a State’s previous commitments to an international legal framework that acknowledges and aims to fight the climate emergency. In Notre Affaire à Tous, for example, the Administrative Court of Paris explained in 2021 that, by ratifying the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement, the French government recognised ‘an “emergency” to combat current climate change’ and ‘recognised its capacity to act effectively on this phenomenon in order to limit its causes and mitigate its harmful consequences’.Footnote 76 One year earlier, in Commune de Grande-Synthe v France, the Supreme French Administrative Court had established the pre-eminence of the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement in the context of domestic mitigation action, explaining that the treaties ‘must be taken into account in the interpretation of provisions of national law’ aimed at reducing GHG emissions.Footnote 77

The status of international law within the domestic legal order is highly relevant to judges’ considerations of a State’s international commitments. When courts are asked to determine the relevance and meaning of international law in domestic proceedings, they usually enjoy additional discretion. They act as gatekeepers determining which international norms meet the domestic requirements of enjoying direct effect and what the relationship between domestic and international norms is. Hence, reliance on international norms as the basis for a ruling rather than, for example, national constitutional law increases the power of the judiciary vis-à-vis the other branches. At the same time, the legislature does not have the same powers over the creation of international norms as it has over national laws, even if it may be formally involved in the ratification of international agreements. Thus, giving effect to international norms, in particular in relation to national laws, may be prima facie read as disempowering parliament. Separation of powers concerns may increase if decisions rely predominantly on international norms rather than national laws.

Very different constitutional framework conditions establish very different conceptions of separation of powers, for example that the judiciary is given the explicit mandate to review the constitutionality of general laws (Germany) or not (Netherlands). However, this does not exclude replicable best practices from emerging, such as reliance on non-binding norms of international law or (repeated) political commitments to substantiate a particular mitigation obligation.

6.4.3 A Matter of Protecting Human Rights

Where there is a right, there is a remedy.Footnote 78 The right to a remedy when one’s rights are violated lies at the heart of the rule of law and separation of powers. Generally, human rights are seen as the prime example of rights for which the judiciary must offer remedies to enforce them against the executive and the legislature. In line with this, the Dutch Supreme Court, followed by several other national courts, emphasised that it is for the courts to ensure that the other branches do not overstep the law when exercising their political discretion, particularly when human rights are at stake.Footnote 79 When assessing the scope of judicial scrutiny in the context of human rights protection, the Municipal Court of Prague in its first instance decision in Klimatická žaloba stated that ‘[i]n accordance with the precautionary principle, persons have the right to be concerned about the quality of their environment and do not have to wait until the climatic conditions are so unfavourable that they do not allow the fulfilment of their basic needs of life’.Footnote 80 This line of reasoning appears to broaden the protection of human rights by establishing that persons may enforce their rights before a(n irreversible) situation of severe human rights violation has occurred. This is particularly meaningful in the context of the climate emergency, which is a cumulative global common action problem, that is, every ton of CO2 emitted anywhere in the world creates an irreversible temperature increase that changes life on Earth.

Separation of powers concerns in human rights adjudication play out in different ways. On the one hand, judges may consider that separation of powers weighs in favour of exercising judicial review because (human) rights protection at the end of the legislative cycle lies at the centre of their role within a democratic system.Footnote 81 On the other hand, human rights adjudication is seen as a field where judges are necessarily empowered vis-à-vis the other branches because judges need to give meaning to open-textured norms and balance interests.Footnote 82 This could support an argument in favour of more judicial restraint. At the same time, it appears relevant whether the rights norms that the court relies on were produced with the democratic legitimation of the domestic law – or even constitution-making process – or whether they emerged from international treaty-making.Footnote 83 In the case of the latter, additional considerations relating to the empowerment of the executive in external relations come into play.

Perhaps the most innovative decision so far has been the decision granted by the High Court of Lahore decision in the Leghari case, as it resulted in procedural obligations for a breach of substantive duties.Footnote 84 The Court created a Climate Change Commission composed of representatives of key ministries, NGOs, and technical experts to monitor the government’s progress in terms of its own climate change policy and implementation framework. In other words, while refraining from imposing higher substantive targets, the Court established the institutional framework to oversee the execution of the State’s existing policies.

Another highly relevant point on the judicial mandate to protect human rights was made by the Superior Court of Quebec, when it noted in ENvironnement JEUnesse that ‘in the case of an alleged violation of the rights guaranteed by the Canadian Charter, a court should not decline jurisdiction on the basis of the doctrine of justiciability’.Footnote 85

The need to exercise judicial review over executive but also legislative action has been particularly recognised as a result of the growing scientific evidence of the ubiquity and intensity of interferences with human rights caused by the climate crisis. This connects to the widely shared understanding that protecting the rights of individuals, including large numbers from foreseeable harm in the future, is the core task of courts under separated powers.

6.4.4 Developing Legally Enforceable Norms from Best Available Science

The Dutch Supreme Court in Urgenda relied heavily on the IPCC reports to argue that ‘objective’ standards exist against which to review the State’s conduct.Footnote 86 This highlights the role of courts as independent fora, where impartial judges need to be convinced, not only of what the law is and what legal obligations may flow from it within the particular case but also of the climate science that should underpin any political and judicial decision-making on climate issues.

Generally, many courts have heavily relied on climate science for their reasoning. Examples include the case of Friends of the Irish Environment, in which the Irish Supreme Court found that the scientific understanding of the ‘safe temperature rise target’ in Article 2.1(a) of the Paris Agreement has increasingly gravitated towards ‘a lower figure […] in the region of 1.5°C’, as scientific knowledge has developed since the Paris Agreement.Footnote 87 Furthermore, the Administrative Court of Paris recalled in Notre Affaire à Tous the IPCC’s findings in the Special Report on 1.5°C (2018) and concluded that ‘a warming of 2°C rather than 1.5°C would seriously increase these various phenomena and their consequences’.Footnote 88 Similarly, in Klimaatzaak, the Court of Appeal pointed out scientific evidence regarding the risks of exceeding the threshold of 1.5°CFootnote 89 and, in Milieudefensie, the Hague District Court converged towards the same conclusion, establishing that ‘in the last couple of years, further insight has shown that a safe temperature increase should not exceed 1.5°C’.Footnote 90

One may conclude that climate litigation necessarily brings science back into the debate, ideally in a rational, non-interest-driven, and fact-checking fashion. By relying on the IPCC reports as reflecting the best available science established in a transparent and inclusive process that vouches for its scientific impartiality, judges vest climate science in the societal debate with legal authority.Footnote 91 In all climate litigation cases, judges are required to establish the relevant facts underpinning the claims of the parties on what reduction obligations flow from the law. While this point may prima facie appear only indirectly linked to separation of powers, it reinforces the function of the judiciary to rationalise societal conflict pursuant to pre-established procedural rules and, by doing so, offers a procedural mechanism of systematically debunking scientific myths that lacks in the less formal political debate, for example, in parliament.

Judges have also justified why climate issues are justiciable irrespective of the complex science involved, the alleged uncertainties under the scientific models sketching the probable impacts of rising emissions, or the numerous interests affected by the impacts and mitigation measures. On the first aspect, the German Federal Constitutional Court acknowledged in Neubauer that, while there are several scientific methods for determining a State’s necessary emissions reductions to hold global warming to a particular temperature limit, all of which entail uncertainties, ‘this does not make it permissible under constitutional law for Germany’s required contribution to be chosen arbitrarily. Nor can a specific constitutional obligation to reduce CO2 emissions be invalidated by simply arguing that Germany’s share of the reduction burden and of the global CO2 budget are impossible to determine’.Footnote 92 Similarly, the Hague District Court established in Milieudefensie that while ‘no one single [reduction] pathway is the measure of all things on a global scale’, there nevertheless exists ‘widely endorsed consensus’ regarding the minimum emissions reductions that are required to avert dangerous climate change.Footnote 93

It should be added that judges must often decide based on incomplete knowledge and rely on science to substantiate their fact finding.Footnote 94 This is not different in climate cases; yet, increasingly detailed science on the impacts of climate change are seen by judges as providing them with the necessary knowledge to give rulings.

6.5 Replicability

Different courts around the world have interpreted the issue of separation of powers in climate litigation in very distinct ways. Ultimately, the extent to which judicial reasoning relating to separation of powers can be replicated depends on the similarities and differences of the relevant legal elements that determine the national conception of separation of powers. In principle, successful litigation requiring a government to do or not do something in relation to climate change is more likely to be observed in countries that have constitutional or national legal provisions protecting a healthy environment and/or climate.Footnote 95 The existence of national climate framework laws with clear targets, accountability mechanisms, and, in some cases, an explicit mandate for courts to review the implementation of climate laws also provide clarity in ensuring judicial oversight.Footnote 96

Once the legislature has exercised its core function and adopted a law, the court is not supposed to apply and interpret the law. As pointed out by the Brazilian Superior Court of Justice, in countries that have legislation protecting the environment and/or the climate, ‘the judge does not create obligations to protect the environment. Instead, they emanate from the law once they have been examined by the Legislative Branch. For this reason, we do not require activist judges, because activism is found within the law and the constitutional text’.Footnote 97

All four stages of adjudication have a potential for replicability. Even the most far-reaching decisions (level 4) have already been replicated, and, notably, the interpretations used in the Urgenda decision have been discussed at length in other cases in the Netherlands and beyond. ‘Urgenda-type’ cases have been replicated with the aim of holding governments accountable for reducing GHG emissions in Canada, the United States, Norway, South Korea, Ireland, Colombia, and other countries. The Urgenda case was also adapted and replicated as a tort law case in Milieudefensie – another decision that could, in principle, be replicated in other jurisdictions with tort law. Furthermore, decisions from other jurisdictions, while not binding, may provide and have provided persuasive arguments.Footnote 98 This practice on the part of domestic courts makes explicit what has been termed the ‘transnational dimensions of the global climate change case law’.Footnote 99

Even the far-reaching orders of Mansoor Ali Shah in the Leghari case were arguably replicated in the Shrestha case. This type of decision could potentially be further replicable in jurisdictions where there is a constitutional right to life and a judicial willingness to interpret this right to life as including a right to a healthy environment, a right to clean air, and/or other similar rights enshrined in the country’s constitution or human rights law.Footnote 100

While the different expressions of the idea of separation of powers vary tremendously, we see a trend that the justiciability of climate cases against public authorities, as well as the establishment of enforceable obligations, are becoming more widely accepted.Footnote 101 Climate litigation has a strong transnational dimension,Footnote 102 which strengthens the potential for replicability. It can further be expected that climate cases will continue being brought and hence that courts must continue to engage with climate issues under the conditions of an unfolding global climate emergency.

6.6 Conclusion

The central aim of the study has been to identify emerging best practice in relation to how separation of powers has been addressed in climate litigation across a wide variety of jurisdictions and doctrinal contexts. Our account suggests that, while judicial engagement is likely to be diverse, the decisions can be understood in a more systematic way. We have identified four stages of adjudication, ranging in intensity from low to high – justiciability, recognising a right or duty, establishing a breach, and determining enforceable obligations (procedural and/or substantive). Within one and the same case, a lower level of intensity indicates a more functional conception of separation of powers, while a higher level of intensity indicates a more relational conception of separation of powers. Further, we have identified four areas of emerging best practice in progressive climate rulings: the role of the judiciary, giving effect to international norms, human rights protection, and developing norms from science.

Once a climate case is filed, the decision of a court to declare the case justiciable opens a number of avenues for what the court can do and how far it can go within its mandate and in line with the separation of powers. Judges have a choice of establishing a lower or higher level of intervention. Such a choice is bound by a judgment about the institutional competence of the courts. Surely, courts are most likely to respond where the legislature has acknowledged a duty of the State and/or of corporations to act. But judges are also sensitive to the different ways in which separation of powers goals are implicated in a policy domain,Footnote 103 as well as to the severity of the problem that they are faced with.

At the same time, climate litigation is a dynamic field, characterised as a ‘transnational’ phenomenon. As Peel and Lin observe, advocates see their climate litigation work as contributing to the global effort to address climate change, and the cases are often accompanied by campaigns that seek to appeal to an international audience.Footnote 104 Litigants take notice of what cases are being filed and what decisions are given in other jurisdictions, and that knowledge often informs the cases they bring. Similarly, judges are following the decisions given by other courts across borders. The Urgenda decision has already been cited in judgements by courts in several other climate cases, including cases in Australia, Ireland, and Germany. Bold decisions elsewhere therefore can give additional confidence for judges deciding new cases presented before them.