1.1 Corpus Linguistics

Since the 1970s, the development of corpus linguistics has brought about important changes in linguistics and applied linguistics. Corpus linguistics is an approach to the study of language that involves collecting large quantities of naturally occurring language and using specialised software that manipulates that language to obtain information about frequencies, co-occurrences and meanings. The language may be spoken, written or signed, in one language variety or more, and one register or more. It consists of language which has occurred in natural contexts, not as the result of elicitation or introspection. The components of the corpus are texts (whole or partial) and thus consist of pieces of connected discourse. The quantity may range from a few hundred thousand words to billions, though the corpus usually contains more texts than could reasonably be read and remembered by an individual.

What distinguishes a corpus from a collection of digitised texts is that it is formatted such that the application of the software enables patterning to be observed that would be missed by conventional forms of reading. The patterning might consist of collocations or phraseology, or it might associate some language features disproportionately with some parts of the corpus. The output from the software may be lists of items, whether words, phrases or classifications, or it may be sets of numbers visualised as tables, graphs or plots, or it may be simple sets of concordance lines. Whatever the output, it is interpreted in terms of the variety, register or community that the corpus represents.

Thus, doing corpus linguistics involves manipulation and observation of ‘what has been said (or written or signed)’. Although it may be framed in terms of testing hypotheses about what will be found in which contexts, the methodology is less about hypothesis formation and more about moving from observation to generalisation and categorisation of language features. This in itself has implications for what the job of the researcher is taken to be.

Corpus linguistics has had a transformative effect on the study of language. The impact may be said to be ‘inward’ and ‘outward’ facing, that is, affecting the study of language(s) itself and affecting aspects of life that are dependent on language. As this book will demonstrate, corpus studies are often comparative and this has enabled varieties of language distinguished by place, time or context to be studied in greater detail than before. Models of the structure of language are also open to test, but in addition new views of how language might be described have emerged, for the most part giving lexis and phraseology a more important role in that description than before.

Language, of course, is an integral part of many aspects of life and the investigation of language in context has the potential to impact those aspects. Because corpus linguistics studies naturally occurring language, and corpora can be collected from specific contexts of use, it has heavily influenced and extended the scope of applied linguistics. Chapter 6 of this book discusses the impact of corpus linguistics on materials for language learners and teachers. The corpora studied consist of language produced by both experts and learners. The impact is partly practical: learner dictionaries based on corpora can include more detail about how words are used, for example, or the aspects of discourse that are most difficult for a group of learners can be identified from a corpus of their writing. It is also theoretical: large quantities of speech or writing from learners can give insights into the processes involved in acquiring a language and the extent to which individuals and groups vary. Chapter 7 focuses on the role of corpora in investigating how ideas are transmitted through discourse of all kinds, including media discourse and academic discourse. Corpora allow large amounts of text to be considered, allowing questions to be answered such as ‘what is most often talked about in this context?’ or ‘what attitudes are expressed or implied?’ or ‘how are texts structured?’. This can show how coherence is achieved in texts, how knowledge is constructed, and how views of society are normalised.

The availability of corpora has assisted other applications of language study. Answering the question ‘who wrote this?’ has applications in literary study and in forensic linguistics. Studying large amounts of Twitter or blog data can answer questions about what topics are raised in specific forums and how identities are construed on-line. This has applications to discovering patient concerns about hospital services, tracking the spread of political ideas, or identifying malicious communications. The linguistic strategies used to persuade can be identified through corpora, and these are important to the development of knowledge in all fields of study, from physics to history, as well as in applications such as political discourse or advertising. How languages are like or unlike each other has been shown to be a question of relative quantity rather than of sharp distinctions. For example, if each of two languages uses a structure broadly equivalent to the passive, one language may use the structure much more or less frequently than the other. Corpora can be used to study the important field of translation, looking both at ‘what translators do’ and ‘what translators need to know’. Chapter 8 considers a range of applications of corpus linguistics.

Above I suggested that corpus studies can be considered ‘inward-facing’, relating to the question of ‘what language is like’, or ‘outward-facing’, considering ‘what language is used for’. In applied linguistics, and in corpus linguistics, however, these two perspectives interact with and inform one another. To take a case in point: Sinclair’s (Reference Sinclair1991; Reference Sinclair2004) influential study of individual words and their phraseology led to the development of a number of concepts about the structure of language, notably the unit of meaning and the open-choice principle / idiom principle distinction. These constitute a way of describing language that is based on (or driven by) the observation of words in a corpus. The detailed, word-by-word description of English that acted as proof of the unit of meaning concept was made possible by the work involved in compiling a dictionary for learners of English (the Cobuild dictionary, Sinclair Reference Sinclair1987a). The act of deriving the theory of form and meaning and the act of compiling the dictionary informed each other, each of them impossible without the other.

1.2 About this Book

The first edition of Corpora in Applied Linguistics was written about 20 years before this one. At that time, corpus linguistics was a fairly new way of approaching the study of language. It diverged from then more mainstream approaches to language description in a number of ways that have continued to be important in the field, as noted above: a lot of language is collected; it has been produced in natural contexts; software is used to manipulate the language and present it in innovative ways; the language is observed and generalisations made.

Already 20 years ago it was clear that the observations from corpus research could supplement other information. For example, studies of language change over time were placed on a firmer footing because of the large amount of evidence gathered (e.g. Mair, Hundt, Leech and Smith Reference Mair, Hundt, Leech and Smith2003). The same is true of comparisons of registers, putting register variation at the heart of language description (e.g. Biber, Johansson, Leech, Conrad and Finegan Reference Biber, Conrad and Cortez1999). Essentially, statements about the differences between times, places and registers could be made with much more confidence than before. Language descriptions both relied on perceptions of difference but also contributed to how those differences were conceptualised. It also, as noted above, led to new concepts such as Units of Meaning (Sinclair Reference Sinclair2004) or lexical priming (Hoey Reference Hoey2005). Corpus linguistics could offer important support to other kinds of linguistic research but it was, arguably, at its most significant when it disrupted perceptions of language.

Since the publication of the first edition, corpora and the techniques used to study them have expanded in all directions. It has become feasible to compile larger and also more specific corpora. The statistics used have become more complex and are increasingly accompanied by sophisticated visualisations of the data. The challenge for the corpus linguist today might not be ‘how to see the wood for the trees’ but ‘how to see the trees as well as the forest’. Some concepts from corpus linguistics have entered everyday life. Wordclouds based on word frequency lists (or keyword lists) are a common way of representing the ‘aboutness’ of a text. Ngrams tracked across decades of book publication show trends in topic development. Commercial applications and an increase in digitally available texts have led to some of the questions in corpus linguistics being tackled from more computational perspectives, such as the development of algorithms to measure opinions expressed in product reviews (see Chapter 8). Corpus linguistics, however, continues to contribute to, and sometimes challenge, other forms of language study. In particular, the corpus-inspired approach to the unity of lexis and grammar both accommodates and questions approaches to the same issue from cognitive linguistics and from systemic-functional grammar (see Chapter 9).

Because of the vast growth in corpus linguistics in the two decades between the first and second editions of this book, the two editions cover very different ground. This second edition is broader, including references to a greater diversity of approaches. It is also, necessarily, highly selective. Research is exemplified rather than comprehensively surveyed. For the most part, and to keep the project within manageable proportions, discussion is restricted to corpora of English. Following this introductory chapter, the organisation of the book is as follows. Chapter 2 describes types of corpora and discusses the main issues raised in the compilation of corpora. It includes a list of corpora of English mentioned in the book. Chapters 3–5 focus on methodology. Chapter 3 exemplifies how patterns can be observed in corpora and what conclusions can be drawn from these. This might be called the qualitative approach to corpus investigation. Chapters 4 and 5 turn attention to quantitative research. Chapter 4 covers the older and more basic approaches to quantity while Chapter 5 addresses more recent developments. Chapters 6–8 focus on applications of corpus linguistics: to language learning and teaching in Chapter 6, the study of discourse in Chapter 7, and other applications in Chapter 8. Chapter 9 considers an open-ended question: the application of corpus linguistics to language theory. It discusses this first in relation to language as a mental phenomenon, specifically the potential alignment between corpus linguistics and construction grammar. Then the issue is discussed in relation to language as a social phenomenon, specifically the relationship between corpus linguistics and systemic-functional linguistics. Chapter 10 concludes the book with an illustration of the application of corpus studies to an issue that is key to life in the early 2020s: the COVID-19 pandemic.

1.3 Terminology

In this section, some key terms that will be used throughout the book are explained. They are: text, type, token, lemma, wordform, ngram, concgram, tag, parse, annotate and metadata.

1.3.1 Text, type, token

Corpora are often described in terms of the number of texts they contain, the number of tokens, and the number of types. Usually, a text is one of the pieces of spoken or written language that have been taken in their entirety from a natural context and compiled into a corpus. For example, in a corpus of student essays, each essay is a text. Sometimes, however, the word is used slightly differently, for example to describe something that is longer or shorter than a naturally occurring text. Some corpora, for example, consist of texts that are exactly 2,000 words long, which means that the corpus ‘text’ is not the same as the ‘text’ from which it is taken, either being an extract from a longer piece of writing or consisting of several texts combined.

The terms type and token both mean ‘word’, but in slightly different senses. The following paragraph (from Simpson and Montgomery Reference Simpson, Montgomery, Verdonk and Weber1995: 140) illustrates this:

What elements make up a narrative? Providing an answer to this question has become one of the central challenges for a stylistics of prose fiction. Much work in modern narrative stylistics seems to isolate the various units which combine to form a novel or short story and to explain how these narrative units are interconnected. Having identified the basic units in this way, the next task is to specify which type of stylistic model is best suited to the study of which particular unit.

In one sense, there are 84 words in this paragraph. That is, there are 84 sequences of letters separated by spaces or punctuation. The word token is used to mean ‘word’ in this sense: the paragraph consists of 84 tokens. It is also said that the paragraph consists of 84 ‘running words’. However, many of these words occur more than once: a, narrative, units and which occur three times each; stylistics occurs two times; to occurs six times and so on. If each unique word is counted only once, there are 60 words, or 60 types, in the paragraph. As texts get longer, more words tend to be repeated, so the number of types relative to the number of tokens goes down. Texts that are carefully written and contain complex ideas, such as the one above, tend to have more types relative to the number of tokens; texts that are easier to read have fewer types relative to tokens. The type-token ratio (TTR) is often used to compare texts. Corpora are often described in terms of their total number of tokens and types, and the average number of tokens and/or types per text.

1.3.2 Wordform, lemma, stem, ngram, concgram

One notable aspect of this account of types is that each wordform is counted separately. It was said above that there are three instances of the type units in the paragraph. There is also an instance of the word unit, but this is treated as a different type. There is a sense, however, in which the singular unit and the plural units are ‘the same word’. They are said to comprise the same lemma. The same is true for the wordforms eat, eats, ate, eating and eaten, which comprise the lemma EAT. This book follows common practice in indicating wordforms cited from corpora by lower case italics and lemmas by capital letters. It also follows the practice of specifying lemmas by word class. According to this definition, the wordform walk belongs to two lemmas: the noun lemma WALK with the wordforms walk and walks (as in ‘I went for a walk’); and the verb lemma WALK with the wordforms walk, walked, walking and walks (as in ‘I walked two miles’). Following the same principle, the wordforms evident (adjective), evidently (adverb), evidence (noun) and evidence (verb) belong to four separate lemmas. Some software allows the user to specify whether the search for a lemma will treat noun and verb walk as belonging to the same lemma or to different ones. Some pre-processing of a corpus has to be carried out if lemmas are to be identified. This often relies on a dictionary containing information such as that ate and eaten are instances of the same lemma. A more rough-and-ready way of obtaining lemmas is to use a stem approach, which means that a wild-card query is added to a word stem. For example, in building the Coronavirus Corpus (see Chapter 2), Davies (Reference Davies2021) searches for words such as contagious but also for words sharing a stem, such as self-isolat*. This search will find self-isolate, self-isolates, self-isolated, self-isolating, self-isolation and any other forms with that stem.

In the account of type and token above, the stylistics paragraph was divided into individual words, which are sequences of letters separated by spaces or punctuation, but it is possible also to divide it into strings of words or -grams. These can be two words long (bigrams), or three (3-grams), four (4-grams) or any number. The general term is ngram. The second sentence from the stylistics paragraph can be divided into ngrams from 2 to 5, as shown in Table 1.1. Ngrams of a given length can be quantified and compared in the same way as individual words or lemmas are. From Table 1.1, it might be expected that items such as one of the (central), providing an answer to and an answer to this question would appear many times in a corpus of English, while prose fiction or even a stylistics of prose fiction might appear many times in a specialised corpus of stylistics. (These items are shown in bold in the table.) In many cases, however, the recognised phrase would include a variable item. A researcher counting the frequency of providing an answer to may wish to identify also providing an acceptable answer to or providing a response to. The units which might be described as ‘ngrams with a variable slot’ are known as concgrams.

Table 1.1 Ngrams in a sentence

| Providing an answer to this question has become one of the central challenges for a stylistics of prose fiction. | |||

| 2-grams | 3-grams | 4-grams | 5-grams |

providing an an answer answer to to this this question question has has become become one one of of the the central central challenges challenges for for a a stylistics stylistics of of prose prose fiction | providing an answer an answer to answer to this to this question this question has question has become has become one become one of one of the of the central the central challenges central challenges for challenges for a for a stylistics a stylistics of of prose fiction | providing an answer to an answer to this answer to this question to this question has this question has become question has become one has become one of become one of the one of the central of the central challenges the central challenges for central challenges for a challenges for a stylistics for a stylistics of a stylistics of prose stylistics of prose fiction | providing an answer to this an answer to this question answer to this question has to this question has become this question has become one question has become one of has become one of the become one of the central one of the central challenges of the central challenges for the central challenges for a central challenges for a stylistics challenges for a stylistics of for a stylistics of prose a stylistics of prose fiction |

1.3.3 Tagging, parsing, annotation and metadata

These terms are applied to procedures that add information to the material in a corpus. The process of adding the information may be entirely automatic or entirely manual, but is often a combination of the two. Metadata is information about a text, such as the date or place of publication, the genre of the text, or the gender or language background of the speaker(s). In some corpora, the metadata attached to each text can be exploited to build a bespoke sub-corpus to meet the researcher’s needs. For example, the MICUSP corpus (Römer and O’Donnell Reference Römer and O’Donnell2011), consisting of papers written by students at US universities, can be searched to obtain papers written by students at a selected level, or by native or non-native speakers of English, or to obtain papers in a given discipline or of a given genre. This is possible because each text has metadata added to it indicating the level of the student, the discipline and so on.

The term tagging is normally used to refer to the process of adding a part of speech (PoS) label to each word in a corpus. This enables searches and frequency counts that depend on part of speech to be undertaken. It is possible, for example, to compare corpora in terms of the number of nouns or verbs in them, or to find all instances of the noun (but not the verb) walk, or to search for all the adverbs that precede a specific adjective. Tagging is often carried out automatically, but the accuracy of automatic tagging procedures varies, and manual editing is often employed if the corpus is small enough. Tagging is also used as the basis for parsing, where the text is analysed grammatically and the constituents of clauses and groups are identified.

Tagging is one form of text annotation. Other common forms of annotation are error annotation (or error tagging), which is applied to texts written by learners of a language to identify and quantify error types, and semantic annotation, which assigns each word in a corpus to a predetermined semantic set. Annotation of errors is normally carried out manually (and there may be considerable disagreement about what constitutes an error), though there is work on automating the process via machine learning (Buttery Reference Buttery2021). Semantic annotation is carried out automatically, based on a pre-classification of words into semantic sets. (See Chapter 4 for more information and discussion of this type of annotation.)

All forms of annotation involve the development of a tag-set. This may be a list of parts of speech, a list of error types, or a list of semantic sets.

1.4 Commonly Used Resources

At the time the first edition of this book was written, there were few publicly available corpora and associated software resources. There are now many. A short list of the best known are listed here. A list of frequently used corpora is given in the appendix to Chapter 2.

Antconc (laurenceanthony.net) is one of a suite of programs developed by Laurence Anthony. Researchers can use it to perform tasks such as concordancing, obtaining lists of collocates, finding lists of keywords, etc. on their own corpora. Antconc is constantly being revised to introduce new features.

English-Corpora.org (English-corpora.org) is a collection of ten US corpora and seven other corpora, with associated software, compiled by Mark Davies. The US corpora include the Corpus of Contemporary American English, the Corpus of Historical American English, the News on the Web corpus and the Corpus of American Soap Operas. The corpora and software are accessed on-line.

#LancsBox (corpora.lancs.ac.uk/lancsbox) is a suite of corpora and associated tools developed at Lancaster University by Vaclav Brezina and others (Brezina, Weill-Tessier and McEnery Reference Brezina, Weill-Tessier and McEnery2020). It can be used with the ready-made corpora included, or researchers can use it with their own corpora. It includes annotation and visualisation tools. It is downloaded for use on the user’s own computer.

SketchEngine (sketchengine.eu), developed by Adam Kilgarriff, is a suite of tools including concordancing, collocations, Word Sketch, a thesaurus and many others. It contains hundreds of ready-made corpora, in over 90 languages. Users can upload their own corpora into SketchEngine and use the tools on those corpora. The corpora and software are accessed on-line.

Wmatrix (ucrel.lancs.ac.uk/wmatrix) provides tools such as concordancing, collocations and keywords. It was developed by Paul Rayson. Users can upload their own corpora, which can be annotated with Part of Speech tags and with semantic tags using the USAS tag-set (see Chapter 4, Section 4.8) and can obtain key PoS and semantic categories as well as keywords.

Wordsmith Tools (lexically.net/wordsmith) is another suite of programs, this one developed by Mike Scott, that can be used on the researcher’s own corpus. The set of tools includes condordancing, keywords, a concgram finder and others. Like Antconc, it is frequently revised. The 2020 version includes a facility to link concordance lines to video files.

1.5 Corpus Linguistics: A Personal View

Corpora are often used to test hypotheses about language, but one aspect of corpus research that is often stressed is the ‘serendipity’ of corpus research, when looking at the output from a corpus investigation tool leads to surprising and exciting insights. My own first introduction to corpus linguistics (courtesy of a talk given at the University of Surrey by Jyl Francis) included a sample of concordance lines for the adjective possible. This is an adjective with a wide range of uses, far more than similar adjectives such as probable or impossible. Identifying those uses convinced me that this new way of looking at language was both informative and exciting.

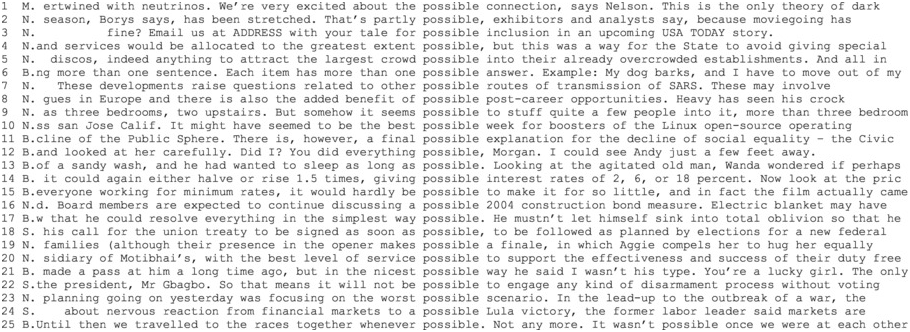

To conclude this chapter, then, I shall attempt to replicate that experience. The corpus I use here is the Wordbanks Online corpus from HarperCollins, which uses a version of the SketchEngine search software (wordbanks.harpercollins.co.uk). There are 107,735 instances of possible in this corpus. For the purposes of illustration I have selected a sample of 250. That is too many lines to show here, so the lines are first ‘shuffled’ (put in random order) and then 25 successive lines from the middle of the set have been extracted and are shown in Figure 1.1. In this figure the lines are numbered and letters used to show the source of the line: B(ook); M(agazine); N(ewspaper); S(poken). The word possible is an adjective and in some lines the expected behaviour of adjectives is observed: it is attributive, as in the possible connection (lines 1, 3, 6, 7, 8, 11, 14, 16, 24), and it is predicative, as in That’s partly possible (line 2). In some lines it is followed by a to-infinitive, as in it seems possible to stuff quite a few people into it (lines 9, 15, 22). There is also the expected sequence ‘as + adjective/adverb + as + possible’, as in as long as possible (lines 13, 18). The list of uses continues with the sequence ‘the + superlative + noun + possible’, as in the greatest extent possible (lines 4, 5, 17, 20) and a variant ‘a/the + superlative + possible + noun’, as in the worst possible scenario (lines 10, 21, 23). There are three further lines illustrating other uses: did everything possible (line 12), whenever possible (line 25), and ‘make + possible + noun phrase’ – makes possible a finale (line 19). The random 25 lines illustrate 9 different patterns of use. Returning to the 250 line sample, more instances of each of these can be obtained. Some examples are shown in Table 1.2. Two additional uses with MAKE have been found, exemplified by make the development possible and make it possible to… The phrase if possible has also been found. These are added to the end of the table, making 12 patterns in all.

Figure 1.1 Concordance lines for possible from Wordbanks Online

Table 1.2 Patterns of possible in 250 random lines from Wordbanks Online

| Pattern | Examples |

| possible + noun | …a possible merger… …a possible leak or fire… …a possible evacuation of 1,000 Canadians in the …face possible deportation …looking for possible connections…the extent of possible brain damage… One possible avenue… …the possible resumption of diplomatic ties… two of the possible intermediaries… |

| link verb + possible | Anything’s possible. …to come back if it’s possible …that love is possible for all of us I still think pressure is possibleA deal for devolution is still possible… Was such a thing possible? |

| it + be + possible + to | It’s possible to provide information to the publicit will not be possible to engage any kind of disarmament pro It is possible to support the battle against terror …it is possible to rid yourself of any fear… It must be possible for people to have access to the air…why it wasn’t possible to think of nothing at all It was possible to see clearly what war had wrought |

| it + be + possible + that | …so it’s possible I could play in the future …it is possible that families with multiple occurrences… It is possible that those persons of rank… It is possible the bouncing movements of running could Was it possible that all the vermin in the world..It is quite possible that Jem became a member of this brother |

| as + adv/adj + as possible | …he’s as far away as possible from the trophy… …had wanted to sleep as long as possible… …try and help them as much as possible… …dealt with as quickly as possible… …are as similar as possible… …call her as soon as possible…appoint an administrator as soon as possible… …murdering people as violently as possible… |

| the + superlative + noun + possible | …attract the largest crowd possible …the greatest happiness possible… …in the most efficient way possible… …in the most horrible way possible… |

| a/the + superlative + possible + noun | …the best possible situation you could be in …make the best possible recovery from her ordeal…He has kept in the closest possible touch …the highest possible price …in the nicest possible way… …at the simplest possible level of argument… …the worst possible scenario… |

| proform + possible | …did everything possible……tried everything possible… …whenever possible… …wherever possible… |

| make + possible + noun phrase | …made possible a much closer relation……a man who made possible the initial contact… …and thus make possible a form of competitive coexistence. |

| make + noun phrase + possible | …that made such a development possible The trip was made possible by… |

| make + it + possible + (for noun) + to | the appointment made it possible for him to pursue researMechanization would make it possible to produce in 25 working |

| if + possible | … are told to hold fire if possible…I like to use Scottish wood if possible …by Christmas if possible… |

The conclusion might be that possible has a large number of behaviours, or is used in a large number of patterns, or, to borrow the term from cognitive linguistics, occurs in a large number of constructions (see Chapter 9). Some of these are almost unique to possible (e.g. if possible, as soon as possible), in that possible can be replaced by a very limited range of adjectives, notably available, though it can be replaced by a phrase with can (if we can, as soon as you can). Others are shared with all other adjectives, being the regular attributive and predicative uses (e.g. the possible explanation / the red bicycle or it’s possible / it’s desirable). Some patterns are shared with a sub-set of adjectives including probable and likely (it is possible that… / it is probable that…). Others are shared with a sub-set of adjectives including easy and difficult (it is possible (for her) to… / it is easy (for them) to…; make it possible / easy for him to…). These observations are summarised in Table 1.3.

Table 1.3 The adjective possible compared with other adjectives

| Pattern | Example | Pattern is used with… |

| possible + noun | …a possible merger… | any adjective |

| link verb + possible | Anything’s possible | any adjective |

| it + be + possible + to | It’s possible to provide information… | adjectives such as easy, difficult, impossible |

| it + be + possible + that | It’s possible I could play in the future | adjectives such as probable, likely, impossible |

| as + adv/adj + as possible | …as soon as possible | no adjectives, but replaceable by you can |

| the + superlative + noun + possible | …the largest crowd possible… | possible, available |

| a/the + superlative + possible + noun | …the best possible situation… | possible, available |

| proform + possible | …tried everything possible | possible, available |

| make + possible + noun phrase | …a man who made possible the initial contact | adjectives such as feasible, achievable |

| make + noun phrase + possible | The trip was made possible by… | adjectives such as feasible, achievable |

| make + it + possible + (for noun) + to | The appointment made it possible for him to pursue research… | adjectives such as feasible, achievable |

| if + possible | …by Christmas if possible | no adjectives, but replaceable by you can |

All this suggests that possible has a wider range of meanings than most adjectives. Some are associated with epistemic modality (what might be the case: it is possible that…) and with deontic modality (what should or can be done: it is possible to…). Table 1.2 also suggests that another distinction can be made, between possible associated with the superlative and extremes (as soon as possible; everything possible; the best possible situation; the greatest happiness possible) and possible associated with cautious assessment (it is possible that…; it might be possible to…). This illustrates the interconnection between form and meaning, and more specifically the importance of patterning, or phraseology, in recognising meaning. It also illustrates the value of seeing many examples of a specific form, possible in this case, in a format that highlights similarity in the immediate co-texts (in Figure 1.1 and Table 1.2).

Much of this information about possible could be found from other ways of encountering language, including introspection. To me, though, seeing the patterning in concordance lines offers a unique perspective that provides affective as well as intellectual satisfaction. This book will discuss methods that go far beyond concordancing, but the joy of identifying what was previously unknown will be a recurring theme.