The future of comics is in the trash can.1

In 2019, calls for futures of comics are still in the air. At least, this is what is suggested in the title of the online platform “Futures of Comics,” meant to support new initiatives in the making and sharing of comics, launched by Ilan Manouach – a multidisciplinary artist best known for his radical comics détournements and for producing a tactile system of communication for persons with visual disabilities called Shapereader. The website page opens onto an image of Felix the Cat melancholically dragging his feet around towering racks of blade servers. This opening image encapsulates the ambiguities of digital cultural memory: it serves as a reminder of the very concrete reality of the hardware and energy-demanding material infrastructures needed to sustain new ways of storing, sharing, and accumulating information.

The Internet has not concretized older hopes for a memory machine or a mode of automatic archiving as its users have grown accustomed to its shutdowns, dead URLs, general link rot, decaying hardware, and digital obsolescence.2 Online archives effectively require constant maintenance work, human labor, and repeated actions and contributions – as indeed do libraries and archives in bricks-and-mortar buildings. But online archives also unsettle the professional forms of archiving by prioritizing other issues and unsettling the chronology of their uses. As De Kosnik notes in her conceptual description of these “rogue archives,” modeled on fan fiction archives, “memory has gone rogue in another sense: where it used to mean the record of cultural production, memory is now the basis of a great deal of cultural production.”3 In the digital environment, the membrane between archiving and making becomes thinner than ever: “At present, each media commodity becomes, at the instant of its release, an archive to be plundered, an original to be memorized, copied, manipulated – a starting point or springboard for receivers’ creativity rather than an end unto itself.”4

The recirculation and the manipulation of comics archives have a long history in a comics culture that largely had to develop its own modes of preservation and transmission, moving between Bill Blackbeard’s files of newspaper comic strips and the different swipe files kept by cartoonists. In both cases, archiving was always considered less an end unto itself than a means to different ends. Bill Blackbeard wore on his sleeve the pirate imaginary of his family name, as played up in the portrait included in his Destroy All Comics interview, which depicts him handling old newspaper volumes clad in pirate gear.5 The swipe files of Chapter 5 also reflect archival gestures as they result from the process of clipping and collecting images, organizing them according to particular processes, and facilitating their reuse. Swiped images are often selected and preserved on the basis of their direct utility, so as to be easily reused in specific circumstances, but they also constitute a reader’s memory and a repertoire of visually striking images. Digital networks, however, do make a difference in that they increase the speed, scale, and scope of such processes, which also means that contemporary readers are faced with an overabundance of material to sift through. This prospect returns us to one of the more complex arguments made by Jared Gardner in his inquiry into the puzzling ubiquity of archives and collectors at the turn of the millennium, as it overlaps with the spread of the personal computer and digital networks. As much as graphic novels have resisted a wholesale digital transition more steadfastly than their competitor media, Gardner argues, comics “ha[ve] been navigating the database of modernity for over a century,” training their readers for what Lev Manovich described as the “database logic” that new media are pushing as the unmarked symbolic form of our digital times.6

As comics become digital files, and as comics are increasingly used as visual archives to draw from, sample, and remix, the feedback loop between archiving and making yields particular gestures of transmission and raises new questions – a prospect embraced by the Futures of Comics website:

In an age where public libraries are an endangered institution, collections run by amateur librarians emerge as new, vital topographies of sharing. Confronted with an unprecedented amount of texts and images, contemporary comics artists are consistently expected to challenge conventional notions of creativity and authorship by engaging with archival research, appropriation, iterative and sampling techniques and other practices of mediation.7

Manouach’s call for the contemporary comics artist is evocative of and alludes to the conceptual poet Kenneth Goldsmith’s proposition of “uncreative writing”: “faced with an unprecedented amount of available text, the problem is not needing to write more of it; instead, we must learn to negotiate the vast quantity that exists.”8 The mission of the “uncreative poet” in the digital age requalifies a series of gestures that have otherwise been thought of as belonging to the peripheries of traditional creative work: organizing, distributing, disseminating, archiving, curating, framing, copying, displacing, and other acts that prioritize handling existing material rather than creating from scratch. An important lesson that comes from managing this thicket of available matter is the realization that a mere change of context raises unanticipated issues, foregrounds unthought-of possibilities, and hence generally speaks volumes about the text it transforms as much as its inseparability from a host of social, cultural, and material assumptions. Manouach’s experiments with comics, as we will see, bring to bear different “uncreative” gestures that reconceptualize comics archives.

Placed under the general act of “undrawing,” this last chapter delves into self-knowingly “uncreative” practices that problematize notions of drawing in the graphic novel, engage with extensive forms of redrawing, or circumvent the activity of drawing in favor of the multitudinous handling of existing graphic matter.9 This chapter thus offers a limit case in this inquiry in terms of the objects and gestures it charts, broadening the scope of the corpus and pushing against its chronological and geographical boundaries. It expands the scope to include some European cartoonists as a comparative counterpoint; and, in terms of period, it principally focuses on works of the last decade (say, 2012–19). It also bears on a younger generation of cartoonists, even if there are crossovers with the generation at the core of this book. As such, it helps put the 2000s into perspective as a distinct moment in the history of the graphic novel, while trying to identify and delineate more recent trends. The institutions of the book trade, the university library, and classrooms are not the main settings for this chapter, which shifts focus to practices more in line with the art world or with the medley of digital culture. It gathers a flurry of sources and objects, published either online and/or as small-press editions, as a way of illustrating the variety of the contemporary field: such comics objects are often looking more toward poetry than the novel, and substantiate a significant trend in art comics and graphic poetry that has grown from the kernel of the contemporary graphic novel.

“That’s Stealing”

The application of “uncreative” protocols to comics does not take place on a tabula rasa: comics are already saturated with practices of reproduction, imitation, continuation, appropriation, pastiche, and other iterative acts. The sheer predominance of swiping in comic book culture shows how much comics making relies on repetition and copying. It is part of its working as a cultural industry to systematize production processes in such a way that it indefectibly involves a large segment of supposedly “unoriginal” labor, if we understand originality to be a relevant shifting criterion of aesthetic evaluation and appreciation in comics history.10 At the same time, it is also the history of comics’ industrial production and collaborative authorship that becomes of renewed interest to contemporary cartoonists interested in forms of appropriation and remixing.

At the same time, and as much as the graphic novel is rife with explicit references to comics history and consciously evocative of past graphic traditions, it has also been extremely wary of “appropriation” as a procedure derived from the visual arts, especially when imbued with the resentment against pop appropriations of comics images. Originality, personal expression, individualized graphic style are cornerstones of the graphic novel that are not always easy to reconcile with the logics of appropriation and strategic unoriginality found in digital culture today. A small anecdote told by Chris Ware about his art school years at the Art Institute of Chicago is revealing of these tensions:

I actually had a teacher tell me to ‘appropriate’ Lyonel Feininger’s work. I was just showing the work to him because I thought Feininger’s cartoons were incredible, and he said, ‘You should use them.’ I said, ‘What do you mean use them?’ He said, ‘You should put them in your work to make it art. Appropriate them. Everyone is doing it.’ I said, ‘That’s stealing.’ I got really mad at the guy. I didn’t get as mad as I should have. It was just stunning!11

The anecdote expresses a shared resentment in comics culture toward the art world, here specifically aimed at art trends in the 1980s in the United States, where it became common to reuse images from the massive stockpile of low media, advertising, magazines, celebrity images, and of course comics in order to carry out an explicit ideological critique of the so-called American way of life.

Even while there was a certain outspoken resistance to remixes, collage and sampling were not completely out of order before the spread of personal computers as we can find uses that foreshadow uncreative practices in the 1970s and 1980s, facilitated by the wider availability of Xerox machines, and that will find a particular echo in the United States through the avant-garde magazine RAW edited by Françoise Mouly and Art Spiegelman. Setting the tone, Spiegelman had already experimented with cut-and-paste in his famous two-page story “The Malpractice Suite,” published in Arcade in 1976, the post-underground magazine he coedited with Bill Griffith.12 The two pages offer a self-reflexive play on the hors-cadre of the newspaper comic strip Nervous Rex, as Spiegelman photocopies panels into larger drawn frames, offering a grotesque extension to the original drawings. As of 1980, the Italian cartoonist Stefano Tamburini serialized in the pages of the Milanese periodical Frigidaire a similar but longer intervention, completely based on the manipulation of an existing comic by means of xeroxing: Snake Agent is a reworking of Mel Graff’s Secret Agent X-9 that proceeds by sliding the originals as the Xerox machine duplicates the image, using the reproduction technology to distort the drawings and rework the process into a different narrative.13 Snake Agent is a landmark in the repurposing of reproduction technologies, precisely one that was used to share and circulate older comics, for creating a completely different work.

Similar exercises in remixing would take place in RAW, whose editors were turned to Europe and undoubtedly aware of Tamburini’s experiment, with the influx of Robert Sikoryak and Mark Newgarden, two cartoonists emerging from the School of Visual Arts where Spiegelman was lecturing.14 Practitioners of the traditional short form and experts of the cartooning gag, they drew many short contributions to the magazine in the mid-1980s. Mark Newgarden’s three-page “Love’s Savage Fury,” for instance, proposed a mash-up of two famous comic strip characters – Ernie Bushmiller’s Nancy and Topps company’s Joe Bazooka – in a highly formal design that visually recounts the story of a brief subway encounter.15 The short comic was drawn in a strict graphic style that made both comics converge in their unabashed minimalism and the diagrammatic simplicity of their drawing: this made Nancy suited to widespread syndication and shrinking newspaper space, just as Joe Bazooka was from the start meant to be read on the tiny formatting of bubble-gum packaging. Intuitively drawn for rescaling, they become suitable matter for reuse and appropriation, which can in part explain why Bushmiller’s characters Nancy and Sluggo have such a record history of being appropriated both in and outside the comics world. A trainee at RAW magazine, Robert Sikoryak similarly worked to conceive comics mash-ups, based on the contrasted juxtaposition of rigorous visual imitations of comics styles and the appropriation of existing texts. “Good ol’ Gregor Brown,” one of his first and most famous examples, crosses Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis with Charles Schulz’s Peanuts.16 Juxtaposed in word and image, the modernist angst of Kafka’s canonical novella and the mellow melancholia of Peanuts reflect on each other – a process that Sikoryak has extended in several combinations yielding Masterpiece Comics, offering a general parody of the 1950s literary adaptations in comics in the style of Classics Illustrated.17 In these cases, the drawings are handmade, but they abandon the idea of a “personal style” in favor of the conspicuous citation of recognizable graphic styles. Or, rather, Sikoryak’s distinct style and author profile on the graphic novel scene lie in this specific mobilization of quoted graphic styles and genres that juxtapose text lifted from other contexts – positioning him as the “master of the comic book mash-up” in the comics world.18

Sharing Redrawing

Sikoryak’s approach proved successful in the digital environment and his more recent work precisely honed in on a form of uncreative writing that works with digital platforms and textual materials copied from online sources. Terms and Conditions: The Graphic Novel offers a take on the iTunes Terms and Conditions contract: Sikoryak’s intervention refits the text of the legal document into the speech bubbles of various pages redrawn from all periods of comics history.19 The copied pages are precisely redrawn in their original cartoonists’ styles with, as the only alteration, the integration of electronic devices and a recurring Steve Jobs figure as the main character. Before being published by Drawn & Quarterly, the pages of Sikoryak’s Terms and Conditions were posted on a regular basis through a dedicated Tumblr, where readers could suggest potential pages or titles for redrawing, co-constructing the archive that Sikoryak ultimately used as a graphic basis: this led to a wildly varied and disparate trajectory through comics history, jump-cutting through periods, genres, and traditions and spanning a chronology that stretches from a 1905 Little Nemo Sunday newspaper page to a 2014 page from Raina Telgemeier’s young-adult graphic novel Sisters.

While comics history is reused and cited at a one-page ratio, the uncreative dimension of Sikoryak’s intervention holds in the dissociation of text and image and in the complete and “unabridged” reuse of a legal contract: where graphic adaptations such as Classics Illustrated were based on the idea of offering more readable versions of classics that no one otherwise read, as suggested in the “abridged” versions of the long literary masterpieces, Sikoryak reversed the process and tried to have his readers read, in full, a text and contract they consent to and sign every day but rarely ever read. By contrast with previous experiments, the type of document chosen, the amount of text that is reused, and the number of images that are redrawn are what align the project with the principles of exhaustivity that guide exercises of uncreative writing. Mimicking the layout and format of traditional comic books and the logo colors of Classics Illustrated, Sikoryak’s Terms and Conditions presents itself as the “complete & unabridged,” “unauthorized adaptation,” making its iterative dimension very clear and questioning the reader on the very legibility of such documents.

That Sikoryak chose to first publish his pages for Terms and Conditions on a Tumblr platform and to produce zine versions not only is telling about the tentative nature of the enterprise, especially as it possibly borders on copyright infringement (although the transformative nature of the work appears quite clear), but also suggests that such practices have become a common part of networks of reading, sharing, and drawing in online comics communities. Sikoryak’s trajectory thus illustrates how such practice of redrawing, remixing, and mash-up have become part of the “practice of everyday (media) life,” as Lev Manovich argues, as cultural industries have integrated the tactical modes of bricolage and customization as part of their strategies.20 A telling example is the “Redrawn” Tumblr curated by Charles Forsman and Melissa Mendes, which calls its followers to “Pick a random page of comic. Redraw it. Post it here,” suggesting that the page-based redrawing protocol used by Sikoryak is one that is common in the online community of comics makers and readers and that, furthermore, tends to diminish the separation between professional and amateur productions.21

If old comics shared on digital platforms might sometimes appear as sheer graphic fodder for mash-ups, severed from their historical productions and circulations, redrawing is also found to be used as a way of expressing attachment and admiration, casting new light on forgotten works. The cartoonist Kevin Huizenga, for instance, has redrawn an entire story from the Dell comic book series Kona, Monarch of Monster Isle, a monster comic drawn by Sam Glanzman and written by Lionel Ziprin.22 The pages are drawn faithfully, respective of layouts and reproducing the same dialogues, but they are done in Huizenga’s personal drawing style, adapting the genre constraints to his own capacities, character styles, and shifting it to black-and-white with added gray-tones. By redrawing the comic without altering the story, Huizenga makes this older work function simultaneously in its original monster genre (a real craze in the 1960s) and in the contemporary domain of alternative comics.23 The comic is done with overt admiration for the original artist; its main functions are presented as a drawing exercise, an explicit expression of admiration, and a means of sharing a forgotten comic book with a contemporary audience that is unlikely to otherwise encounter or go to such types of production. Tagged as “fan art” on his blog, the act of redrawing paradoxically obscures the style of the original cartoonist while otherwise valorizing his work and career.24 Within an economy of digital reproduction, the amount of time and care invested in the physical redrawing of pages, applied at an entire story length, enacts a specific way of sharing an older comic book, bearing the stamp of its reader.25

This is also telling in a different exercise of redrawing by Derik Badman, which selects another Dell comic book: turning to a Gene Autry western comic title from 1948 drawn by Jesse Marsh, he redraws the entire story but uses redrawing as a way of selecting and erasing parts of the document, effacing all traces of human presence in the comic book and implementing a new narrative. Stripped to zones of black-and-white and abstract backgrounds, Badman reworks the popular comic book into an abstract comic and a piece of graphic poetry.26 If Badman’s intervention is more transformative, he similarly shares an online version of the original comic book that serves as the basis for his contribution. Through the cases of Sikoryak, Huizenga, and Badman, figures emerging from the alternative comics scene, the popularity of redrawing as an exercise on microblogging platforms and zines appears to manifest a continued attachment to drawing as individual expression and craft within practices of extended redrawing and a digital economy of sharing past comics.

British cartoonist Simon Grennan has also relied on redrawing as a form of representing old, forgotten works to new readers – but his practice of redrawing serves as a useful counterexample to the previous cases. Linked to a large project of recovery of the graphic work of Marie Duval, a “maverick Victorian cartoonist” who drew in the pages of the London comics serial Judy and who was practically forgotten in histories of British comics, Grennan has indeed produced a series of redrawn images that dialogue with this collective archival project.27 With his work titled Drawing in Drag by Marie Duval, Grennan proposes to update the comics not by redrawing them in a more contemporary and personal style but, on the contrary, by performing drawing as Marie Duval in the twenty-first century.28 The project evolves both from the careful study of Marie Duval’s work and its archival recovery – Grennan and his peers Roger Sabin and Julian Waite created a publicly accessible online repository of her drawings, The Marie Duval Archive – and from the cartoonist’s previous experiments with redrawing. As part of his research on narrative drawing, Grennan has indeed practiced various forms of “drawing impersonations,” trying to embody other socialized practices of drawing, whether individual styles or genres, as an attempt to work through complex theoretical questions and engage with problems of appropriation.29 From this background, Grennan plays with the situation of Marie Duval as a “vulgar” cartoonist and stage performer on the British Victorian scene, which involved acts of gender-swapping (both on stage and on paper, as she did sign on a few occasions as “Ambrose Clark”) in Drawing in Drag by Marie Duval. A kind of companion piece to the reprint of Duval’s drawings, the book adopts her loose drawing style, her page compositions, and the humor of her work – which focused on the familiar lives of lower-class readers and the newly accessible urban leisures – and reproduces specific pages to adapt them to twenty-first-century British urban pleasures and fashion trends (another of Duval’s favorite targets). In “Pull, Pull Together,” for instance, Grennan portrays the performance of working-class masculinity through a series of details in clothing and behavior (Figure 6.1). The humor relies on the recognizability and familiarity of the situation: in this, contemporary readers are arguably meant to partake in the shared humor that Marie Duval’s drawing style would have occasioned with its intended readers. By contrast with the aforementioned practices of redrawing, Grennan thus attempts drawing as Marie Duval would have today.

Comics Samples

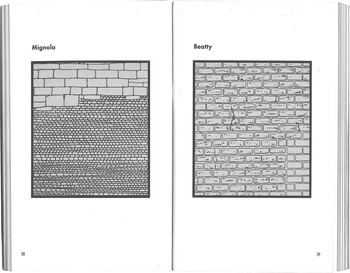

While Sikoryak, Huizenga, and Badman practice systematic redrawing, they remain close to an emphasis on the act of drawing as expression of a personalized style (even in the case of Sikoryak, whose pastiches gradually coalesce into a recognizable drawing style). Other cartoonists have adopted different gestures of making that put at a remove the practice of drawing itself, based on the sampling of existing comics works and the selection and manipulation of comics fragments. A good example of this raising of the stakes is provided by Canadian cartoonist Mark Laliberte, whose comics poetry book BRICKBRICKBRICK assembles a set of bricks, retraced and recomposed from the backgrounds of comics history.30 The book is a collection of single panels filled with bricks as drawn by an impressively wide variety of cartoonists. The square panels condense a graphic element that is often glanced over as mere backdrop and blows it up as a peculiar index of its artist’s style. Emerging from intense research and rereading with particular attention, the building of these various brick walls follows a strange drawing process: part scanning, part digital reworking, part original copying. By manipulating samples taken from a wide range of comics works and refitting them as measurable data – unified in their size, scale, and graphic presentation – Laliberte’s graphic intervention allows an auteurist reading of brick details, as evincing idiosyncratic ways of drawing brought about by their contrastive presentation, while anthologizing those brick poems according to narrative or thematic criteria (Figure 6.2). Each comics poem paradoxically appears, in a way, as testament to the individuality of graphic style. The collection demonstrates the many different ways of drawing such a seemingly simple background detail, which becomes an index of personalized drawing styles attributed to a range of comics creators working in very different contexts: Laliberte focuses both on recognizable graphic styles and major artists in the field – from newspaper comics legend Charles Schulz to alternative comics idol Julie Doucet – and on lesser-known figures in the field, such as Colin Upton, from the Canadian mini-comics scene, or John Beatty, who has worked as an inker for Marvel and DC.

Figure 6.2 Double-page spread from Mark Laliberte’s BRICKBRICKBRICK (Toronto: BookThug, 2010), 38–39.

A striking example of “poetry by other means,” BRICKBRICKBRICK exposes the literal bricks of comic book architecture, drawing the background to the foreground and presenting brick-drawing as an inventive variation of a theme within a constrained narrative form.31 A well-practiced collagist, Laliberte describes his creative process as one of “drawing without drawing.”32 Laliberte’s BRICKBRICKBRICK immediately foregrounds some of the tensions that run through such questions. It adopts an auteurist approach, echoing fans’ construction of individual genius in the industry (sometimes resulting from quasi-forensic investigation of graphic details) but recasting that attention on creators who have been frequently unheard of – only to undercut the same rhetoric of originality by its very reliance on an ambiguous citationality.33 Laliberte here assumes a tactical role as curator, compiler, sampler.

Such practices of sampling are further facilitated online by the publicly available material repositories. Online repositories of public domain comic books such as the Digital Comics Museum, which provides its subscribers with access to a range of comic books from publishers that were driven out of business by competition, censorship, or general media change in the 1950s, provide material that is easily reused. As Kalervo Sinervo reckons, comic book scanning in the United States has been specifically constructed as a participative fan activity, largely removed from profit motives and with a particular preservationist dedication; as a result, “comics piracy catalyzed the formation of a creative commons in a niche online public,” apparent in the open-sourced digital formats of comic book scans, such as CBR or CBZ, which directly allow, if not call for, such appropriations and remixing.34 This is exactly what the French cartoonist Samplerman does, assembling cropped details from the files available online to constitute a repertoire of forms – the digital equivalent to a swipe file – that he can rework in his digital collage compositions (Figure 6.3). In transforming scans made available by fan archivists, Samplerman draws attention in his work to the circulation of comic books in digital contexts. Indeed, the visual aesthetics of his collages play up repetition effects that are not available in traditional print collage, limited by the relative scarcity of materials to cut from. Many of Samplerman’s collages use mirror effects, duplication, and layering that foreground the particular affordances of digital image editing software. By keeping the aesthetics of comic book scans, with their faded colors and newsprint backgrounds, these collages play up the recognition of familiar images against their distortion. Samplerman’s work alternates between absurd but narrative-driven collages – unfolding over several pages and integrating speech bubbles – and single-page collages – prioritizing abstract layouts that defamiliarize the conventional structure of the comics page.

Distributing Drawing

The work of Ilan Manouach, to some extent, can be read as a return to Tamburini’s Snake Agent and to the use and hijacking of technological infrastructures as a meaningful gesture in itself. Cutting through disciplinary practices, merging conceptual critique with praxeological experimentation, Manouach’s work undercuts the usual trajectories in comics as well as the auteur model of the graphic novel. A cartoonist’s path is often traced as a particular and often difficult relationship to graphic style: developing an individually recognizable drawing style is key in the graphic novel, but is also a hard-won enterprise. Trained to that very approach at the Saint-Luc art school in Brussels, and certainly endowed with the technical craftmanship to develop such a style, Manouach rapidly turned to exploring radical modes of making comics without drawing. His line of work is perhaps better described as a continuous process of withdrawing, of disengaging himself from the stylistic singularity that usually shapes the making and reading of graphic narratives.35

Throughout a diverse set of comics works he defines as “conceptual comics,” Manouach has relied on a myriad of appropriative techniques, applied to a range of works that is as diverse. One of his first uncreative works opened onto an erasurist gesture: he selected a title of the Danish children’s comic series Rasmus Klump and withdrew all its characters save for the one, lone-standing Riki the pelican, a relatively minor figure in the fixed cast of characters.36 The narrative becomes a strange story of a funny animal talking to himself while passively observing how a farm seems to build itself, how fields are plowed by an invisible workforce, and of course ending with the traditional but now strangely superlative pancake banquet. The pages of the comics have been carefully photoshopped so as to leave as little visible trace as possible of the graphic intervention. And, indeed, the book itself is faithfully reproduced in the editorial style of the Casterman albums. This first experiment settled a set of ground rules for Manouach’s next projects, often published with La Cinquième Couche: the appropriation is minimal and carefully focused; it bears on a complete work that is reproduced in facsimile; it leads to a generative displacement of the work and its surrounds. The most famously controversial piece in this series of works was Katz, in which Manouach and his peers reproduce Art Spiegelman’s canonical graphic novel Maus, only replacing all animal characters with cat heads, blurring the ethnic codes of representation that the graphic novel installs. The book ended in a litigation with the French publisher, which led to the legally performative destruction of the entire stock of Katz copies, including its digital files. The case, amply documented in MetaKatz, reflects back on what makes a work canonical, the complicated intricacies of Holocaust literature and book destruction, and copyright issues in appropriation.37

While the case of Katz ended up driving most attention to the terms of the debates (reopening the discussions around the animal conventions set up in Maus) rather than its material outcomes (few copies of which survived), Manouach’s Noirs opened up new avenues for a more conscientious reflection on materiality proper. Noirs is a reprint of Peyo’s 1963 Les Schtroumpfs noirs, an album in which a black fly wreaks havoc in the Smurfs’ village by biting the tails of the little blue cartoon characters, infecting them, turning them into mad black smurfs whose only obsession is to further spread the contamination: the obscuring of these color differentiations is used to bring the racist undertone into sharp focus. Manouach’s intervention here again proceeds in an erasure, this time stretching further into the impersonality of the process by relying completely on the printing technology, filling in the ink toners of the four-color CMYK with but one single color, CCCC. Cyan takes over, eats all the other colors, and makes the comics partly illegible (Figure 6.4). In doing this, as Pedro Moura brilliantly argues, Manouach is not only launching a direct attack against the racist underpinnings of comics heritage, as they can be found in Peyo’s Les Schtroumpfs noirs; he is also making a statement about or against expression, presenting an object that steps “out of the realm of authorial expression, and even of human expression, in order to discharge lines of depersonalized expression, as it were. In this case, the expressivity of the very materiality of the album’s four-color printing.”38 As Moura notes, the fabrication of this reprint nevertheless takes a series of preparational gestures to produce a printable file: in this sense, Noirs is not simply a blue-only print; it also bears some marks of the assembling process. The flatbed scanning of the original album, which projects a bright light source on relatively thin paper, produces effects of transparency in the lighter zones of the image, partly imprinting the verso onto the recto page. Each page of Noirs thus bears traces of both sides of the paper as a kind of surplus excess resulting from the copying process.

Figure 6.4 Ilan Manouach, Noirs (Brussels: La Cinquième Couche, 2014), 9.

This kind of material specificity is further put to work by Manouach in his Compendium of Franco-Belgian Comics, a broader book that compounds forty-eight albums typical of the Franco-Belgian comics production, gleaned in Brussels’ secondhand stores.39 This stockpile totaled 2,304 pages that the artist scanned and detoured to establish a large set of samples of the most typical units that make the “language” of Franco-Belgian comics. These samples are then layered in situ, according to the same spatial coordinates on the page. The result yields a compendium of prototypical fragments, each one evocative of its original context and yet reframed in a collage-like composition that disrupts their narrative function. The ensemble highlights the relative uniformity of Franco-Belgian comics, while advancing an implicit material critique of the semiotic perspective on comics as a grammatical language.

In mapping the vernaculars of Franco-Belgian comics, Manouach’s Compendium is a sort of companion volume to his Blanco, which “merely” consists in a completely blankforty-eight-page hardcover album, save for the removable sticker that functions as the caption to this conceptual artwork.40 “Blanco” in French means “dummy,” the print jargon for the blank prototype used by printers as a mock-up for testing the result beforehand, getting a sense of what the book will look and feel like, whether the binding will hold. A dummy is generally needed for books that deviate from standard publishing norms: this is precisely what the comics album in France is not, given the level of format standardization in the comics industry. In producing a dummy for what Jean-Christophe Menu famously dubbed the 48CC (quarante-huit pages cartonnées couleur), Manouach puts on the market an object that reflexively calls our attention to the invisibility of material formats in comics culture.41 Even while Blanco displays none of the visible signs of comics, its sheer materiality is enough to immediately tell us we are dealing with a bande dessinée. Through its circulation in the various contexts and settings of the social world of comics, the blank object contrastingly becomes a sounding board and echoes everything we would otherwise pay little attention to: distribution platforms, book tables, online retailing paratexts, reviews, festival participants – all become meaning-making agents imbuing Blanco with a particular function. The dummy, in this sense, performs knowledge work, accruing its meanings in the ways that it circulates and is used.

This series of conceptual books shares a genealogy with a long avant-garde history of blank objects, illegible texts, appropriations, and found objects. While sharing affinities with the erasurist techniques common in the realm of artists’ books, these bookworks do not participate in the speculative logics of planned scarcity, unique editions, and limited runs – nor does Manouach pursue the artisanal techniques, handicraft, and specialized printing processes that are so present on the European alternative comics scene. Rather, his reflexive use of materiality is one that highlights the multiple agencies at work, human and nonhuman, by staging the withdrawal of the loudest of voices. The extensive logic here also bears on the technological uses, establishing productive overlaps with post-print and post-digital thinking – two notions that concur in a less binary narrative of technological change and that prioritize an understanding of mediality across the board.42 De facto, Manouach’s works trump the faultline between print and paper that has been continuously driving the debates around digital comics over the past decades. His printed books arise from micro-gestures of digital composition and collation required for the purpose of appropriation, processes that are mundane in the digital age. At the same time, Manouach has also extended this line of thought by increasingly relying on machinic processes (coding and programming are the contemporary cartoonists’ required tools), maneuvering globalized digital networks to produce works reflective of these widespread changes in terms of readerships, circulations, and labor.

In doing all of this, Manouach continues to inquire into what it means to read comics, who or what performs the work of “reading,” and how that activity plays out in the digital age. His latest projects involve the micro-reworking of comics by online laborers: compiling and assembling collections of images that are distributed to digital micro-workers through a crowdsourcing platform. This global cast of workers are remunerated on the basis of the very small tasks that they perform online. Manouach thus breaks down existing corpora of comics into more or less minimal units that are then subjected to specific appropriation and transformation depending on the task assigned to workers across the globe, from Malaysia to Uganda. The Cubicle Island is an inquiry into this new form of digital labor, an attempt at catching its office culture, and an ode to the tactical behaviors of online workers: it is a heavyweight, 1,000-plus-page collection of New Yorker desert island cartoons that have been uncaptioned and sent to thousands of micro-workers, expected to “provide a funny text between 50–70 words for each of these cartoons.”43 The mammoth volume binds together all of the results, juxtaposing the good puns alongside the spam (indeed, micro-workers, to try to increase efficiency, program bots to perform some very specific tasks). What emerges from this sea-wave of unsorted recaptioned cartoons is the messiness of a digital marketplace where human laborers and automatized machinic surrogates cooperate in ways that are sometimes hard to tell apart. Some cartoon captions are actual jokes; others vary between YouTube links, illegible series of letters, found texts, extensive fragments excerpted from public domain novels, misunderstood guidelines, accurate descriptions of the cartoon image, social media profiles, and many other types of writing. The Cubicle Island is thus a collection that updates the kind of “Xerox-lore” that was found in the office culture of the 1970s and 1980s, when employers would deviate the photocopying machines to other uses.44 Equally, it is a reflection on the anomie of this kind of labor, where the cubicle becomes an ever more solitary and isolated one, where work hours extend into the twenty-four/seven regime of late capitalist production and where tactical behaviors are all that is left within an extremely precarious form of immaterial labor.45

Peanuts Minus Schulz, published by Jean Boîte éditions as part of its “uncreative writings” series, extends these interests and distributes the large corpus of Charles Schulz’s Peanuts comic strip to a range of micro-workers from around the world. The book documents the protocols, which requests online workers to read a specific comic strip then, “On a white piece of paper, get ready to copy the comic strip by hand, as precisely as possible” – adding a range of more specific campaigns that are possible: “A2. Insert yourself in one of the panels” or “F6. Make a manga version of the strip.” In doing this, Manouach scales up the practice of redrawing to a wide collective body of online workers, usually commissioned to perform small and precise tasks. Relying on the largely unregulated platforms of crowdsourcing labor, Manouach aims not to upscale comics publishing industries or to construct an entirely streamlined comic book. Rather, he turns to Peanuts as an immensely popular and heavily merchandised comic strip, embodying the tension between the mark of a single cartoonist – Charles Schulz – and the commercial derivatives that his work led to. As already broached before, Schulz’s graphic heritage is also posthumously managed by a series of creatives responsible for adapting the comic strip to a variety of commercial occasions, under strict guidelines of franchising management. Manouach seeks to play out these tensions by having worldwide readers of the comic strip, caught in a precarious labor condition, perform a striking task: redraw a few panels, “as precisely possible,” adding their own signature to the comic strip.

Effectively relying on common notions of drawing as trace, drawing here becomes a paid task that makes visible the workers as they perform it: the variety of drawing capacities and talents, of creative misunderstanding and self-proposed additions, the rewriting of dialogues in different languages – all of these aspects highlight individual approaches and affective responses to the performed task, with some regular contributors returning across the pages. One worker consistently draws himself into the strip, adding short autobiographical comments in the margins of the redrawn Peanuts gags. The 700-page book thus assembles a sundry assortment of redrawn strips outside of the usual circulations of comics; the submissions that arise from this request, as Manouach declares, “radically reconfigure the assumptions made about the individual role different agents can have in a production chain. They underline the very nature of comics as an eternal score subjected to vagaries and contextual instantiations.”46

As he underlines the multifarious potentials for comics as archives to be revisited, reread, and redistributed in constant new forms, Manouach both perpetuates familiar gestures of transmission while flouting traditional practices and professional virtues in the comics world. At the same time, he has also engaged in building a context for such practices of undrawing – often published through extremely ephemeral formats, whether online or in print – by organizing their archival curation and integrating them to existing rogue archives. Manouach’s comics are hosted on online alternative archives such as UbuWeb – a groundbreaking database of avant-garde works founded in 1996 by Kenneth Goldsmith in the spirit of free culture – and he has collaborated to curate an archival collection of “conceptual comics” on Monoskop – an online collaborative wiki and archive for media, the humanities, and the arts founded by Dušan Barok in 2004. Both archives answer to De Kosnik’s description of “alternative archives” (contrasting with “universal” or “community” styles of rogue archiving), which strive to assemble “diverse and robust collections of nonmainstream cultural genres,” while operating in a similar commitment to free and complete access independent of copyright restrictions.47 The conceptual comics made available through these online archives include a wide range of works, all shared in full high-resolution PDF, assembled from photographed reproduction of the flattened books, which emphasizes their material properties, and including an explanatory notice and extra metadata. In some ways, the “Conceptual Comics” collection available at Monoskop can be seen as an updated version of Chris Ware’s McSweeney’s anthology, establishing links and relationship between creators in the present and in the past, and showcasing comics in their specific materiality. The statement of the opening page presents the online collection as “a springboard for establishing the conditions for an affective lineage between similarly minded practitioners.”48 But while Ware’s McSweeney’s anthology tended to foreground a range of original voices expressed in the personality of their graphic style, Manouach’s online collection deviates from the emphasis on auteurs to embrace a wide range of works, many of them based on uncreative processes of appropriation, republishing, sampling, recontextualization, and redrawing.