3.1 Introduction

In a powerful pre-recorded message to the twenty-sixth Conference of the Parties (COP26), Simon Kofe, Tuvalu’s minister of justice, communications, and foreign affairs, stood knee-deep in seawater and described the “deadly and existential threats” that climate change and rising sea levels pose to his country (Reuters 2021). As the second lowest-lying country in the world, and because of its fragile economy and social and environmental vulnerabilities, Tuvalu is severely affected by the impacts of climate change (Government of Tuvalu 2016a). The country has been very active in developing ways of responding to these challenges. It has incorporated climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction measures into its national policies since the second National Strategy for Sustainable Development in 2005 (Government of Tuvalu 2005). Tuvalu has also been active in negotiations under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), both within the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) (Betzold et al. Reference Betzold, Castro and Weiler2012) and the least developed countries (LDCs) group, to demand bold emissions cuts and ask for support to address climate change impacts. With respect to loss and damage, Tuvalu has played a sustained role in climate change negotiations, including advocating for a separate article on loss and damage in the Paris Agreement (Fry Reference Fry2016). The country was also an active member of the Executive Committee of the Warsaw International Mechanism for Loss and Damage (WIM ExCom) from its establishment in 2013 until 2022, when a new set of members were appointed.

As such, Tuvalu represents a “most likely case” for engagement with national loss and damage policymaking: It already faces significant loss and damage and has been heavily engaged with global policy development on the issue. This chapter explores how Tuvalu’s policy actors make sense of and attempt to govern loss and damage at the national level.Footnote 1 Using interpretive policy analysis (Yanow Reference Yanow2000) and thirteen semi-structured interviews with key government and civil society stakeholders, it scrutinizes the way loss and damage is framed both in official documents and interviewees’ words. It finds that loss and damage does not feature as a stand-alone policy domain, nor is it explicitly distinguished from adaptation, but rather is treated as an issue which cuts across different sectors. It identifies, in particular, four policy areas in which the concept of loss and damage is consistently invoked: national sovereignty, climate-induced human mobility, infrastructure investment, and protection of the country’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ). The chapter also discusses how insurance and risk transfer feature as a specific set of measures for acting on loss and damage.

The types of responses to loss and damage that the Tuvaluan government seeks to pursue in these policy areas involve actions that go beyond the national level – including the regional scale and international venues other than the UNFCCC. The chapter suggests that loss and damage in Tuvalu is developing as a “complex governance system” with competencies and agency spanning across multiple scales. It finds that ideas matter when devising certain responses to loss and damage. In particular, “sovereignty” is framed by local actors not only in its physical dimension (authority over a territory) but also in a more intangible way (maritime boundaries as identified irrespective of the impacts of climate change on shorelines). It also suggests that Tuvaluans’ “sense of place” and emotional connection to their location (Corlew Reference Corlew2012) inform their strong determination to prevent climate-induced migration through policy.

3.2 National Circumstances

Tuvalu is a micro-state in the South Pacific Ocean, which is home to around 11,200 people (World Bank Group 2021). Still classified as a LDC, it has met the criteria for graduation since 2012 based on human development indicators and per capita income. However, the United Nations Economic and Social Council decided to defer the consideration of Tuvalu’s graduation due to the special vulnerability to climate change and other environmental shocks the country faces (UN Committee for Development Policy 2018).

The nine small islands composing the archipelago all lie less than five meters above sea level, making it the world’s second lowest-lying country (Government of Tuvalu 2015a). Rising sea levels not only threaten livelihoods in the short term but also pose a long-term “fundamental risk to [Tuvalu’s] very existence” (Government of Tuvalu 2015a). For the largest Tuvaluan island Funafuti, sea-level rise has been “found to be about 3 times larger than the global mean sea level rise over 1950–2009” (Becker et al. Reference Becker, Meyssignac, Letetrel, Llovel, Cazenave and Delcroix2012). Freshwater resources’ quality is threatened by saltwater intrusion, coastal erosion, flooding, and inundation, while their availability is threatened by droughts (Government of Tuvalu 2015b) and land and marine heatwaves (World Bank Group & Asian Development Bank 2021). Changing climatic conditions, including increases in temperature and in rainfall, are also associated with risks to human health, such as vector- and water-borne diseases (Government of Tuvalu 2015b). As qualitative research on the ground with residents of Tuvalu has shown, droughts heavily impact daily life in Tuvalu, and the Tuvaluan participants regarded adaptation to droughts and a better water management as their most relevant adaptation need (Beyerl et al. Reference Beyerl, Mieg and Weber2018).

Irregular rainfall, rising temperatures, and increasingly intense tropical cyclones (IPCC Reference Masson-Delmotte, Zhai, Pirani and Zhou2021, p. 97) are also detrimental to the agricultural sector (Government of Tuvalu 2015a, p. 4), which represents a long-term threat to food security in the archipelago (World Bank Group & Asian Development Bank 2021, p. 13). Prolonged periods of dry weather and hot temperatures, alongside other climate change-related impacts, including ocean acidification, endanger not only fish stocks but also the stability of coral reefs (which are part of the morphological fundament of the Tuvaluan archipelago) through coral bleaching (Government of Tuvalu 2015b, p. 33; see also Becker et al. Reference Becker, Meyssignac, Letetrel, Llovel, Cazenave and Delcroix2012).

Like many Small Island Developing States, the ocean, in particular fisheries, represents a significant proportion of income for Tuvalu and its population. At the plenary session of the 2017 UN Ocean Conference, the then Tuvaluan prime minister, Enele Sopoaga, described Tuvalu as probably “the most fisher-dependent nation on earth” and stressed that 40 percent of the country’s annual national budget derives from the ocean and tuna fishing licenses in particular (Government of Tuvalu 2017c). Tuvalu has an EEZ of around 900 square kilometers (Government of Tuvalu 2015a) where it enjoys the exclusive and sovereign rights to manage natural resources. The country has placed significant emphasis on the future economic growth of the fishery resources contained within it. Yet as sea level rises, low-lying countries will lose their land – which serves as the baseline from which the EEZ is calculated under existing international law – and as a result their EEZ will contract.

3.3 Policy Landscape

Adaptation decisions at the national level are generally driven by the goals and priorities set out in the country’s National Sustainable Development Strategy (Morioka et al. Reference Morioka, McGann, Mackay and Mackey2019). While the first development strategy (1995–1998) did not include environment-related priorities, Te Kakeega II: National Strategy for Sustainable Development 2005–2015 (TKII) explicitly mentioned climate change as a key concern. It identified saltwater inundation of pulaka pits,Footnote 2 coastal erosion, and flooding as the main impacts associated with climate change and sea-level rise and noted how climate events could suddenly reverse development gains (Government of Tuvalu 2005).

Under the impulse of TKII, Tuvalu adopted its first climate change policy in 2012. The policy, Te Kaniva (2012–2021), aims to “protect Tuvalu’s status as a nation and its cultural identity and to build its capacity to ensure a safe, resilient and prosperous future” (Government of Tuvalu 2012a). It is meant to be “cross cutting,” given that “climate change impacts affect every development sector and Tuvaluans’ way of life.” The policy sets seven goals for scaling up the country’s responses to climate change, with a dominant focus on adaptation and disaster risk reduction. Te Kaniva is the first policy document to explicitly mention loss and damage and does so under Goal 1 on strengthening adaptation actions. In particular, Strategy 1.8 calls for defining “appropriate insurance arrangements to address loss and damage from the impacts of climate change” and suggests that the “cost of re-building from the impacts of climate change are primarily borne by major GHG [greenhouse gas] producing countries” (Government of Tuvalu 2012a). Loss and damage is also mentioned in the related Tuvalu National Strategic Action Plan for Climate Change and Disaster Risk Management 2012–2016, which operationalizes the provisions of Te Kaniva by identifying responsible agencies, implementation arrangements, and monitoring and evaluation mechanisms and provides an indicative costing for implementation (Government of Tuvalu 2012b). Specific actions to fulfil Strategy 1.8 include “investigat[ing] and establish[ing] appropriate insurance arrangements to address loss and damage from the impacts of climate change” and seeking funding to fulfil this aim (Government of Tuvalu 2012b). The new National Climate Change Policy, Te Vaka Fenua o Tuvalu (2021–2030) explicitly links loss and damage to the issue of national sovereignty and the safeguard of Tuvalu’s identity and cultural heritage (Government of Tuvalu 2021a). In particular, the policy calls for integrating loss and damage in all adaptation projects and programs, and risk management processes of the government.

Our interviewees further connected loss and damage to two key aspects: (a) the need for an international policy for forced migration due to climate change and (b) the need to protect the EEZ (Interviews 9, 12). On the first point, the government has been pushing in recent years for “a UN General Assembly resolution establishing a system of legal protection for people displaced by the impacts of climate change” (Government of Tuvalu 2016b). During the high-level signing ceremony for the Paris Agreement, Prime Minister Sopoaga specified that the concern was “not an indication that the people of Tuvalu want to migrate” but rather a humanitarian one and that was “one aspect of the Loss and Damage agenda” (Government of Tuvalu 2016b).

The pursuit of a legal instrument at the international level to deal with climate-related migration is at odds with the way the issue is framed in the 2015 Tuvalu National Labour Migration Policy (NLMP) (Government of Tuvalu 2015b). This document, developed by the former Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Trade, Tourism, Environment and Labour in partnership with the International Labour Organization’s (ILO) Office for Pacific Countries, was supported by the EU-funded Pacific Climate Change and Migration Project (PCCM 2014), which specifically promoted a “migration as adaptation” frame (Remling Reference Remling2020). The inconsistency between the international protection instruments sought at the international level – as based on Te Kaniva – and the “migration as adaptation” discourse embedded in the NLMP was flagged as one reason for the delay in the launch of the latest policy Te Vaka Fenua O Tuvalu 2021–2030 (Interviews 1, 2, 12). As one interviewee noted:

In the labor migration policy, it has a different framing, and they have included climate change as one of labor migration, which is to some extent, of course it’s true, but the way it’s been framed, it’s not aligning to what we have proposed and agreed to by cabinet, to look at legal protection of people displaced by climate change.

The protection of the current EEZ, which implies securing sovereign rights over the natural resources it contains, becomes relevant even in a scenario of forced migration due to climate change. As a government official said, protecting the EEZ will allow the country to “stamp it as our waters and, even if we are to relocate at a later stage, we will continue to lay ownership on it” and this will provide resources “so that we can have our own way of developing our own people in the future. … We’d have that territory, a piece of territory” (Interview 9).

Loss and damage is further mentioned in Te Kakeega III (New National Strategy for Sustainable Development): National Strategy for Sustainable Development 2016–2020 (TKIII), which represents Tuvalu’s eighth National Development Plan. In this document, loss and damage features as a strategic stream which rests on several milestones up to 2020 including: (a) identifying options for risk transfer and an insurance mechanism; (b) establishing and implementing a “Survival Plan for Tuvalu,” which would also address the issue of climate-induced migration; and (c) solidifying the concept of loss and damage in national law by amending relevant legislation (Government of Tuvalu 2015a). The 2019 Climate Change Resilience Act has given the concept of loss and damage a legal foundation by including “Addressing loss & damage associated with climate change” as one of its eight policy objectives (Government of Tuvalu 2019a). The Act states that the Department of Climate Change and Disaster (DCCD) shall “formulate, apply, and implement” a national climate change policy and that strategies and plans to implement it should include “secur[ing] funding for … issues related to loss and damage associated with the adverse effects of climate change, including extreme weather events and slow onset events.” Loss and damage is also mentioned under Section 17 on “Precautionary approach,” which states that the lack of full scientific certainty regarding the extent of adverse effects of climate change should not be used as a reason for not acting to prevent or minimize the potential adverse effects or risks “includ[ing] serious or irreversible loss or damage as a result of climate change” (Government of Tuvalu 2019a). With respect to the “Survival Plan of Tuvalu,” we could not find evidence of its development – at least in this form.

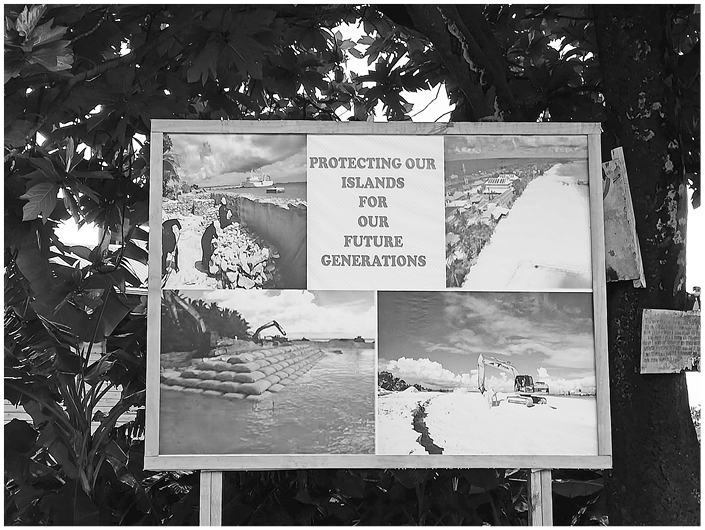

Finally, the Tuvalu Infrastructure Strategy and Investment Plan 2016–2025 (TISIP) – falling under TKIII – identifies climate change impacts causing loss and damage to assets and measures to protect them (Government of Tuvalu 2017b). Impacts include those associated with cyclones (wind, trees falling, destructive waves), storm surges (flooding, erosion), sea-level rise (erosion, seepage), and temperature (health, asset failure). The document understands “loss and damage” in material terms, as the negative impacts to buildings, roofs, foundations, coastlines, and assets like roads, power transformers, generators, and cables (Figure 3.1). It identifies several measures to enhance these assets’ resilience, like enforcing building codes, elevating houses and equipping them with stronger roofs, land reclamation, beach nourishment, and improved design specificities for technological assets.

Figure 3.1 Billboard in Funafuti on Tuvalu’s coastal adaptation project (August 2019).

As this overview of the policy landscape shows, loss and damage is seen in Tuvalu not as a stand-alone policy but as inherently connected to other policy domains. In official documents, it is explicitly connected to three key policy areas: national sovereignty (see Te Vaka Fenua o Tuvalu), climate-induced displacement (see TKIII) and infrastructure (see TISIP). Interviews identified a fourth area associated with loss and damage which concerns the protection of Tuvalu’s EEZ (Interviews 9, 12). This supports the observation by a research participant that “loss and damage cuts across all sectors … we look at … the vulnerable sectors” (Interview 12).

Te Kaniva and TKIII also highlight a specific set of measures for acting on loss and damage, namely, insurance and risk transfer. Since 2016, the government has been working on a proposal for a Pacific Islands Climate Change Insurance Facility (PICCIF), which should overcome the narrow focus on natural disasters of current initiatives – namely, the Pacific Catastrophe Risk Assessment and Financing Initiative (PCRAFI) (World Bank Group 2015) – and specifically target both immediate impacts like cyclones, droughts, floods, and coral bleaching and longer-term impacts like population displacement, ocean acidification, changes in fish stocks, and sea-level rise leading to loss of land and territory. Yet the concept note prepared by the government on the PICCIF emphasized that “insurance is not a universal remedy for all types of loss and damage caused by climate change” and “other supportive finance will be necessary” (Government of Tuvalu 2017a).

The interviews further reveal that public sector stakeholders understand loss and damage along a continuum with adaptation and as an issue that should be dealt with through comprehensive risk management (CRM) approaches. In the words of one stakeholder: “How are you going to really draw the line and say, ‘Okay, I’m going to stop my adaptation here, everything else that comes after that, that’s all loss and damage’? … That’s not very practical …. What policy can look at is the broader picture” (Interview 12). Along these lines, policymakers mentioned that loss and damage would be included in the National Adaptation Plan (NAP) – which aims at consolidating priorities for adaptation across the six key sectors of water, agriculture, fisheries, health, disaster, and coastal protection – in an indirect way. The stakeholder continued:

So the issue now [is that] people … just come and look at your document [and ask] “where is loss and damage?” But it is not necessary to have specific reference to loss and damage but rather, in the explanation of the plan, to say “we wanted to plan this as part of adaptation” but also recognizing that …we need to plan how to mitigate those losses and damages once we get into that phase of loss and damage.

Another government official partially challenged this point by recognizing that the lack of evidence on loss and damage was one of the reasons for it not being mentioned explicitly in the NAP. This was also a driving factor in the push to “look into the more vulnerable issues that need immediate attention” (Interview 11).

3.4 International Engagement

Section 3.3 shows that the Tuvaluan government has sought to develop loss and damage responses by turning to the regional level and international venues beyond the UNFCCC. A key example of action at the international scale is the government’s attempt to develop a system of legal protection within the UN to deal with the issue of climate-induced migration. One such initiative includes the draft resolution “Providing legal protection for persons displaced by the impacts of climate change,” which was presented by the government at the seventy-third session of the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) in July 2019 (Government of Tuvalu 2019b) but did not obtain the required support (Aleinikoff & Martin Reference Aleinikoff and Martin2022). The document calls for the development of “an international legally binding instrument” and rallies the international community, in particular the parties to the UNFCCC, to “take concrete action to meet the protection and assistance needs of displaced persons and to contribute generously to projects and programs aimed at alleviating their plight, facilitating durable solutions and supporting vulnerable local host communities” (Government of Tuvalu 2019b, pp. 3–4). As a high-level government official explained, the aim is to avoid people being put “into a refugee camp” and instead being granted the right to have “some kind of society that they can really live [in],” including “a governing body,” and the opportunity to “practice their culture” and enjoy the “kind of amenities that they used to have in their own location … like hospitals and all of that” (Interview 9). Several interviewees reiterated the need for international cooperation, either in the form of international law (Interview 1) or regional policies (Interview 2) and/or by exploring bilateral arrangements (Interview 6).

Similarly, the protection of the EEZ is pursued in the context of the international negotiations of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). When asked about the connection with loss and damage, a government official explained: “The reasoning behind it is of course because it has linkages to that, but the UNFCCC cannot change our EEZ, it is the Law of the Sea that needs to change our EEZ or ensure that it is established. That’s why it goes to the UNCLOS” (Interview 12). The protection of the EEZ is a common concern across the Pacific region. In 2021, the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF) leaders released the “Declaration on preserving maritime zones in the face of climate change-related sea-level rise,” where they “proclaim[ed] that our maritime zones, as established and notified to the Secretary-General of the United Nations in accordance with the Convention, and the rights and entitlements that flow from them, shall continue to apply, without reduction, notwithstanding any physical changes connected to climate change-related sea-level rise” (Pacific Islands Forum 2021).

Tuvalu has cooperated with several Pacific countries on EEZ-related matters since the early 1990s within the Pacific Islands Forum Fisheries Agency (FFA) and since 2001 within the Pacific Community (SPC). For instance, the Resilient Boundaries for the Blue Pacific project (2020–2022) by the SPC aims to support Pacific countries in assessing and addressing the legal and technical implications of climate change on maritime zones (GEM 2021). The protection of maritime boundaries is a key theme for subregional fishery agreements in which Tuvalu participates. In March 2018, the signatories of the Nauru Agreement signed “The Delap Commitment on Securing Our Common Wealth of Oceans,”Footnote 3 where they recognize the “threat to the integrity of maritime boundaries and the existential impacts due to sea level rise” and agreed to “pursue legal recognition of the defined baselines established under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea to remain in perpetuity irrespective of the impacts of sea level rise” (PNA Leaders 2018).

On the issue of risk transfer tools, PIF leaders have not shown the same unity as in the case of the protection of the EEZ. Here Tuvalu has been leading the endeavors of Smaller Island States (SIS)Footnote 4 to develop a Pacific insurance scheme, the PICCIF, which is meant to compete with the PCRAFI, where the PIF is involved. In fact, the government considers PCRAFI “a top down model and that it does not properly respond to the climate change impact needs of Pacific Island countries” given its focus on natural hazards. The government also expressed concerns that “the premiums are too high and the pay-out too low” (Government of Tuvalu 2017a). While PIF leaders’ response to PICCIF was initially tepid (Newton Cain & Dornan Reference Newton Cain and Dornan2017), they later agreed to hold several workshops and meetings of a dedicated taskforce to develop the concept (SPREP 2020).

Finally, while explicit references to compensation have largely disappeared within the UNFCCC context, Tuvalu has helped to spearhead efforts to seek compensation for loss and damage outside the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement. One research participant noted, when reflecting on loss and damage negotiations in the context of the Paris Agreement: “We always wanted provisions for compensation in the Paris Agreement but realized that to get loss and damage in the Paris Agreement we had to drop our demand for compensation …. Some sort of compensation regime will need to be developed. This may have to be developed outside of the UNFCCC” (Interview 13). At COP26, the prime minister of Tuvalu signed an agreement with the prime minister of Antigua and Barbuda to establish the Commission of Small Island States on Climate Change and International Law (COSIS). One of the first steps was to consider requesting an advisory opinion from the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea on the legal responsibility of states for carbon emissions, marine pollution, and rising sea levels. The aim is to “develop and implement fair and just global and environmental norms and practices, including compensation for loss and damage” (Government of Tuvalu 2021b). At its meeting in August 2022, COSIS decided to establish three working groups, comprising both international lawyers and representatives of member governments, to advance the objectives of the commission.

3.5 Institutions

The Climate Change Department (CCD) plays a key role in climate change adaptation policymaking. Its position in Tuvalu’s institutional architecture has changed over time due to the increasing centrality of climate change as a topic for the country. In May 2015, the Climate Change Unit within the Ministry of Environment merged with the National Disaster Management Office, under the Office of the Prime Minister, leading to the creation of the Department of Climate Change and Disaster (DCCD).Footnote 5 The department was placed under the Office of the Prime Minister so to “have more focus on it” (Interview 9). As one research participant noted, the government at that time saw the “relevance, and … benefit of bringing the two together, given the interlinkages of issues of addressing DRR [disaster risk reduction] and also CCA [climate change adaptation]” (Interview 12). In 2019, the DCCD was moved under the Ministry of Finance and changed its name into CCD. The functions of the CCD in building resilience to climate change are detailed in the Climate Change Resilience Act 2019 (Government of Tuvalu 2019a), while those related to disaster risk management are rooted in the National Disaster Management Act (2008). A key responsibility of the CCD is to support Tuvalu’s involvement in climate change negotiations and in disaster risk management platforms at the regional and international levels.Footnote 6 With specific reference to loss and damage, its director was an active member of the WIM ExCom from its establishment to 2022.

While the CCD’s international activity has been a predominant part of its work, one research participant observed a shift toward more domestic issues after the devastation brought about by Cyclone Pam in 2015:

I think the Department of Climate Change and Disaster, before, they were focused on that international/regional stage. They’re focused on all of the policies for Tuvalu, except that they weren’t focused on the country, they were so focused on getting the message out, that they weren’t actually focused on the people, the Tuvaluans. So after that happened [TC Pam], it was good. There was a huge interest in getting everything sorted out on the ground.

Cyclone Pam also provided a major push toward the establishment of the Climate Change and Disaster Survival Fund (TSF), which was launched in 2016 to support climate change adaptation investments as well as recovery from climate change impacts and natural disasters. While the TSF’s establishing Act states that it can be used to “enhance resilience and protection against climate change and natural disasters,” its main focus is on providing communities with immediate support when a disaster strikes (Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat 2018). The establishment of the TSF in the aftermath of a major disaster might explain its focus on response and rehabilitation/reconstruction rather than on proactive adaptation. Similar to the institutional disruption brought about by Hurricane Dorian in The Bahamas, discussed in Chapter 5, Cyclone Pam seems to have prompted a shift within the existing institutional arrangements, both by adjusting the focus and mandate of the CCD and by driving the emergence of new bodies, such as the TSF.

The CCD serves as the secretariat of the National Advisory Council for Climate Change (NACCC), which brings together different agencies within and beyond the government to ensure collaboration across relevant sectors “like fisheries, agriculture, water, health” (Interview 12) and reports directly to the cabinet. Several research participants pointed to the NACCC as a good practice example of collaboration across different actors working on climate change-related projects (Interviews 7, 9, 12). For instance, one interviewee noted that “getting everyone together, it’s not a challenge that I can think of. Establishing the NACCC was one good way forward that allows us to talk to each other” (Interview 12). Yet other actors even within the public administration tended to identify challenges in collaboration, for instance when it comes to data sharing (Interviews 3, 7). For example, one noted how their department “will want to share the reports, but not the raw data” and how this fact constrains the possibility for other departments to contribute with “views” and “thoughts” (Interview 7). A representative from a large national nongovernmental organization (NGO) similarly remarked that “each department is holding on to their assessment outcomes … and it’s not being shared amongst everybody else” and concluded that “everybody tends to act in silo” and “that’s one of the biggest problems that we have here in Tuvalu” (Interview 3).

3.6 Ideas

This section focuses on how different ideas inform the type of responses that are devised for dealing with loss and damage. It starts by highlighting how climate change is framed as an existential threat for Tuvalu and how the need to protect national sovereignty translates in both formal and physical responses. It then moves on to analyzing the way migration, as a potential response to the loss of national territory caused by sea-level rise, is perceived by many Tuvaluans as a last-resort measure and as a matter of personal choice. In particular, most Tuvaluans refute the narrative often imposed on islanders as the “first climate refugees” and reaffirm their agency in avoiding this outcome. This general attitude is rooted in a strong sense of place which characterizes Tuvalu’s culture. The section concludes by focusing on a second set of ideas which is explored in this book – causal knowledge – and the way it informs policy development on loss and damage.

3.6.1 Climate Change as an “Existential Threat”

Climate change has repeatedly been framed as an existential threat for Tuvalu (Government of Tuvalu 2015a). The protection of the country’s sovereignty is a key concern within national climate policies and initiatives – including those related or connected to loss and damage. The government has attempted to maintain national sovereignty in two ways. First, it has been pursued formally by “climate-proofing” the EEZ in the context of the UNCLOS negotiations, as discussed in Section 3.4. The protection of the EEZ has been framed as an issue of security and national sovereignty since 2012 within Te Kaniva, which stressed the importance of securing the national EEZ “as belonging to the Government and People of Tuvalu regardless of any loss of coastal areas or islands due to impacts of climate change such as sea-level rise” (Government of Tuvalu 2012a).

Second, the maintenance of national sovereignty has been pursued physically through land reclamation initiatives. The government received USD 36 million from the Green Climate Fund (GCF) and invested USD 2.9 million in co-financing, to carry out the Tuvalu Coastal Adaptation Project, which aims at improving coastal protection on the islands of Funafuti, Nanumea, and Nanumaga (Figure 3.1). The proposal submitted to the GCF explicitly mentions the “existential threat” posed by climate change and the need to maintain “the sovereignty of Tuvalu” as key motivations for the project and stresses how “a nation-wide relocation is not considered an official solution to climate change” (Government of Tuvalu 2016a). The project was publicly defined by Prime Minister Sopoaga as “the pride of Tuvalu” (UNDP 2017). The importance of the project for the government is also brought up by an interviewee: “This is the biggest project for Tuvalu, and there’s a lot influence from government. There’s always pressure from them in approaching that, especially the implementation. Sometimes, it’s hard to manage those expectations …. The prime minister is actually the board chairman. That’s how important this project is for Tuvalu” (Interview 5).

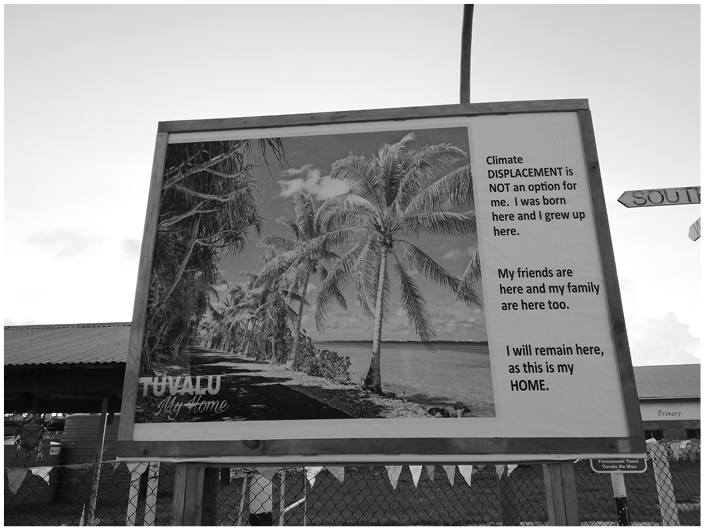

3.6.2 A Sense of Place: Climate-Related Migration and Displacement

As the analysis of the policy landscape shows, climate mobility is an important aspect of the loss and damage agenda in Tuvalu. Yet in contrast to some public and scientific narratives that see islanders as future “climate refugees,” Tuvaluans proudly claim that they do not want to leave the country (Farbotko & Lazrus Reference Farbotko and Lazrus2012), as also displayed in Figure 3.2. As one research participant articulated: “When we talk about climate change it’s really hard for us to tell our feelings, but for me personally, I just don’t want to move out of Tuvalu. Even that I’m working on climate change, also as a climate fighter, but still I don’t agree to migrate or move out of Tuvalu” (Interview 4). Migration is seen as a last-resort measure and framed as a matter of personal choice: The view is that if people opted to migrate, then they should be protected by regional/international frameworks, which is different from being framed as refugees. An officer at the DCCD explained: “Migration is our last resort. … The government doesn’t want the people to migrate as refugees. So they want to have a regional policy. Personally, I think that migration should be a personal option and we should not be framed as refugees. … If people in small island states opt to migrate, then we need to be protected” (Interview 1). This particular way of understanding climate-induced migration is rooted in a strong sense of place in Tuvalu’s culture, which is characterized by an emotional connectedness, attachment, and identity formed from their interaction with their location (Corlew Reference Corlew2012). As Minister Kofe highlighted in his speech at COP26: “In Tuvalu, our islands are sacred to us. They contain the mana [supernatural force or power] of our people. They were the home of our ancestors. They are the home of our people today and we want them to remain the home of our people into the future” (Government of Tuvalu 2021b).

Figure 3.2 Billboard in Funafuti on climate displacement (August 2019).

3.6.3 Use of Science and Evidence

Research participants from the CCD highlighted two related challenges in producing knowledge around loss and damage that can then be used for policymaking: (a) difficulties in conceptually distinguishing loss and damage from adaptation and (b) the availability of comprehensive assessment tools. Talking about the loss and damage to vegetation caused by Cyclone Pam, a research participant recalled: “The World Bank came in and I think ADB [Asian Development Bank] also came in and did those assessments. So there are figures that have been put in place into that, but to distinguish where adaptation stops and loss and damage kicked in it, it’s something that’s very difficult to do” (Interview 12).

The interviewee continued by pointing to shortcomings in current modeling tools and the role the WIM can play in identifying appropriate methods that countries can use. The stakeholder also pointed to the regional universities and the ways in which they could fill relevant knowledge gaps through case studies:

The actual assessments for loss and damage is something that we are still in the process of identifying how best to do this because assessing losses for SOE [slow onset event], it’s something very difficult to do, especially with the data that we have and also the models that we have. Part of the work that the WIM is currently doing is to look at the different comprehensive risk management methodologies and tools that could speak towards loss and damage that countries can be using. … Work that we are doing as part of the region is to look at the university, the USP, the University of the South Pacific, to come up with some case studies that will help. And I think they have done two case studies already.

Given these challenges, evidence around loss and damage remains scarce and this was reported to be one of the reasons why it was decided not to include loss and damage in the NAP (Interview 11).

3.7 Conclusion

This chapter has focused on Tuvalu as a “most likely case” for engagement with loss and damage policymaking at the national level, given its vulnerability to climate hazards, its engagement with key negotiating groups within the UNFCCC process, and its involvement in the implementation of the WIM ExCom’s work. As such, it provides an opportunity to better understand the way loss and damage as the conceptualization of a governance problem originating in the global climate regime is translated into national processes (Roberts & Pelling Reference Roberts and Pelling2018).

Table 3.1 synthetizes the main results from our analysis along the four dimensions of the analytical framework we developed in Chapter 2. A key finding from the analysis is that loss and damage does not feature as a stand-alone policy domain nor is it explicitly distinguished from adaptation, but it is rather treated as a cross-cutting issue. The case of Tuvalu highlights that the conceptual separation between adaptation and loss and damage, which is pursued by some actors within climate negotiations, does not necessarily translate into national practices. Loss and damage in Tuvalu is instead seen along a continuum with adaptation and as an issue to be dealt with through CRM approaches. Indeed, relevant loss and damage measures are explicitly included in adaptation, disaster risk reduction, and sustainable development policies.

Table 3.1 Summary of Tuvalu

There are four areas in which the concept of loss and damage is consistently invoked: infrastructure investment, climate-induced human mobility, sovereignty and protection of the country’s EEZ. The area of infrastructure investment suggests a physical and monetary understanding of loss and damage, framed as the negative impacts to buildings, coastlines, and assets. The latter two, instead, refer to those adverse impacts of climate change which are difficult or impossible to quantify or monetize and which are called noneconomic losses in the lingo of the UNFCCC (Serdeczny et al. Reference Serdeczny, Bauer and Huq2018). These policy areas, that is, human mobility and loss of sovereignty, show the crucial role that ideas play in shaping the way national policy actors frame the problem of loss and damage and its possible solutions. Similar to findings from previous studies (Farbotko & Lazrus Reference Farbotko and Lazrus2012), Tuvaluans refute narratives depicting them as future “climate refugees,” express their desire to remain in their islands, and see climate-induced mobility as a matter of personal choice. On the protection of the EEZ, the government seeks to preserve current maritime borders regardless of any loss of coastal areas and thus teases out the concept of sovereignty from that which focuses exclusive on control over a physical territory.

Responses to loss and damage involve actions beyond the national level – including the regional scale and international venues other than the UNFCCC. For instance, Tuvalu has been leading the endeavors of Smaller Island States to develop the Pacific insurance scheme (in competition with the PCRAFI); it has attempted to develop a system of legal protection within the UN to deal with the issue of climate-induced migration; and it is campaigning for the protection of the EEZ within the UNCLOS. Loss and damage is emerging in Tuvalu as a complex governance system, with competencies and agency distributed across a variety of actors operating at multiple governance scales.

The CCD plays a key role in loss and damage policymaking in Tuvalu. Yet, other national actors stand out as important in developing and enacting loss and damage-relevant policies. These include, for example, the Ministry of Environment, Foreign Affairs, Labour and Trade, which is responsible for delivering the National Labour Migration Policy; the Ministry of Public Utilities and the Ministry of Economic Development in the field of infrastructure; and the Ministry of Works and Natural Resources with responsibility for EEZ issues. Loss and damage does not yet seem to play a significant role in discussions within civil society organizations or NGOs, probably due to the fact that it is a relatively new concept in the national landscape. Future research might draw attention to a diverse set of actors that can be influential in national approaches to loss and damage policymaking, both at the government level and beyond.