5.1 The Intensity of Human Interaction and Its Functions

In the prior chapters we have outlined the distinctive properties of the interaction engine, shown how it impinges on the cognitive processing of language and sketched the role it may have played in the evolution of our communication system. In this chapter we ask what has really been driving these developments? The argument will be that the social functions of human communication have been central, and that tracing these can throw interesting light on the quality of our relationships and the architecture of social systems.

It has been estimated that humans spend up to 30 per cent of diurnal hours in conversational interaction. This must of course vary across societies, and across occupations and personalities, but in any case, it is a considerable commitment of time, in some cases second only to sleep. Chimpanzees are said to spend up to 20 per cent of their time grooming, their equivalent of the social exchange represented by casual talk, but again it varies considerably across groups, and some hardly groom at all. Moreover, human interaction involves far greater niceties of politeness, tact, and informational adjustment, and thus much more thought and circumspection than physical grooming. Chimpanzee grooming stimulates endogenous opioids – they clearly get great pleasure from being groomed. But humans have upregulated the expression of endogenous opioids in the brain – we are veritable pleasure junkies, and some of our greatest pleasures come from social interaction.Footnote 1

Clearly, social primates are occupied a lot in servicing their relationships, but humans stand out as intensely social in terms of the time and energy put into interaction. A cross-cultural sample suggests that on average individuals spend over four and a half hours a day chatting, outputting some 16,000 words in a two-hour stream, divided into 1,500 turns at talk.Footnote 2 Human infants seem to come into the world pre-prepared for this: from birth, human infants prefer gazing faces,Footnote 3 experience more mutual gaze than their chimpanzee counterparts, and are rapidly encouraged into exchanges of facial expressions and vocalizations.

The question then naturally arises, what is all this interactional time and effort about, what drives it? There are a number of different, although related, theories. One idea is that it is the cost of the widespread cooperation that characterizes human groups – a behavioural tendency that runs against the individualism built into evolutionary process. The only way we can have developed cooperative instincts is by catching people who cheat – the ‘free riders’ who take the benefits but don’t pay the costs. By exchanging copious amounts of information on a daily basis, free-riders can be detected and ostracized. Gossip, on this view, has a policing function.

Another idea is that all social primates service their social relations in order to keep their friendships and protective alliances, find potential mates, and appease aggressors. As groups get larger the costs of one-to-one servicing get greater, because the number of possible connections grows exponentially: there are three dyadic connections between three people, but 1,275 between fifty people. So, the argument goes, it would be better to have a broadcast means of servicing multiple relationships at once – much more efficient than scratching each others’ fur! Moreover, servicing one’s relationships by voice leaves the hands free to continue work. Of course, evolving a communication system of the complexity of language solely to mentally tickle one’s companions seems unlikely – there must have been additional social or ecological demands.

A third idea is that theory of mind, once acquired, opens up a vast mental universe to explore, including learning all the survival tricks that cultures provide, and assessing whether other people’s thoughts and plans are useful to one’s own. But the only reliable access to that gigantic world of others’ warnings, plans, hopes, and dreams is through copious communication.

A fourth theory is that human relationships are particularly fickle things, requiring constant assessment and modulation of interaction. Because of the complexities of human culture and political systems there is more to be gained and lost, and more ways to gain and lose them, than in other primate societies. Building trust by sharing information, experiences, and insights into other individuals would constitute a means of forming alliances and groups essential to survival.

There may be a grain of truth in all these closely related accounts. Let us review them in a little more detail. The recognition of the ‘free-rider problem’ has its origins in philosophy and economics: how to ensure all contribute to a collective solution for the public good. ‘The tragedy of the commons’, where individuals over-exploit natural resources because if they don’t others will, is a long-recognized problem. The counterpart in game theory is the prisoner’s dilemma, where if two robbers both stay silent they will get lenient sentences, if both squeal they will serve long sentences, but if only one squeals he will be freed and the other will get an even more lengthy sentence. The rational optimal strategy is to defect, to squeal in this case. This poses a serious problem for a theory of evolution by natural selection operating over the fitness of individuals – how can cooperation ever evolve? In evolutionary theory, where fitness (number of offspring) is the payoff, it takes very special conditions to make both altruism and cooperation pay. The game theory view is that it will only pay to cooperate if there are sanctions against betrayal, participants are initially willing to give cooperation a chance, and moreover they are willing to pass up the optimal payoff.Footnote 4 Trust based on prior cooperation can obviously play a crucial role in a succession of ‘games’, so reputation matters. If reciprocity engenders trust over repeated events, then cooperation can evolve. But what if the defector or free-rider decamps? Then they can move elsewhere and keep exploiting individuals. (The original ‘confidence man’, William Thomson, persuaded people in the 1840s he was an acquaintance they had momentarily forgotten, got many of them to lend him their watches, before absconding far away with the watch and never returning.)

The solution to the free-rider problem, it has been proposed, is gossip – we can poison the well for the confidence trickster by warning everyone about them. On this view gossip might have played a critical role in the evolution of cooperation in an articulate species.Footnote 5 Unfortunately for the theory, empirical studies of gossip show low percentages of negative information or criticism of other persons: 4 per cent or less of conversation time in Western samples, but possibly higher in small-scale communities. Although we lack much comparative data, this small amount of negative gossip is in line with my own data from small-scale Mayan and Papuan communities, where illness and the exchange of valuables were the main topics of conversation respectively. Catching free riders certainly does not appear to be the central function of conversation (see Section 5.2).Footnote 6 So although catching them may be an important side-effect of frequent interaction, it seems unlikely to be the primary motivation for the sheer scale of the investment in human interaction.

We turn to the theory that the main job of conversation is to service social relationships in groups too big to allow effective grooming or one-on-one bonding rituals. The primatologist and psychologist Robin Dunbar developed the theory that encephalization (brain weight, and particularly neo-cortex size, relative to body size) correlates with primate group size, suggesting that the evolution of the brain has been driven by the need to service social relationships, keeping alliances strong for joint protection against bullies in the group, winning mates, and maintaining foraging companions. The encephalization data are appealing, permitting for example guesses at the group sizes of extinct hominins.Footnote 7 Extrapolating from the curve associating brain size and group size, humans should have a maximal group size of around 150 meaningful others. Of course, this does not seem to capture the demography of modern societies, but Dunbar argues that nevertheless the number is reflected in effective cooperating organizations, like office sizes, army units, or Christmas card lists. He also claims that the number is reflected in the ethnographic record for tribal societies, in the effective unit that may be labelled a ‘clan’, and also in the size of villages. Dunbar allows that within the maximal group of 150, there are nested sub-groups in multiples of five: we have five loved ones, fifteen good friends, fifty wider friends, and 150 meaningful others – beyond that are people one may recognize but have little to do with. This nested pattern makes the theory a little hard to falsify. My own judgement is that the magic number 150 doesn’t match the ethnographic record very well, in part because demography depends on subsistence system – for example Aboriginal Australian groupings both in terms of action groups and networks do not match the picture.Footnote 8

It is actually unlikely given the huge variety of human subsistence and residence patterns that we can easily generalize about the size and structure of the human networks of relationships. Nevertheless, all that is actually crucial to Dunbar’s theory is that human group sizes are larger than can be serviced by dyadic interactions, so humans developed a broadcast communication system to replace primate grooming strategies. The idea is that a broadcast communication system would give a 3:1 advantage over other primate grooming as a bonding mechanism, reflected in the thrice greater size of human groups over chimpanzee groups (in his estimate 150 over 50). But this supposed advantage of conversation over grooming is based on the assumption that grooming is done on a one-to-one basis, which is frequently not the case: it can be mutual, or chained over five or more individuals. Computations of the number of conversational partners versus actual grooming practices show the alleged advantage of the broadcast medium almost entirely disappears.Footnote 9 Besides, as we noted earlier, the need for a more efficient soothing, itch-reducing mechanism seems scant motivation for the complexities of language. Regardless of the fate of Dunbar’s numerology, the idea that the increasing neocortex size in primates is related especially to social cognition is clearly a valuable insight.

The third idea is that the theory of mind opens up a vast new territory of things to learn, things that can only be learnt through communicative interaction. The acquisition of a theory of mind is indeed computationally explosive – instead of thinking about others as simply physical entities, essentially billiard balls with complex trajectories, theory of mind opens up the Pandora’s box of others’ motives and reasoning. One can distinguish first-order theory of mind, what an individual thinks another thinks, from second-order attribution, namely what an individual A thinks another B thinks about A. Higher-order attributions are possible – what A thinks B thinks that A thinks about B: that would be a third-order attribution. Deception may involve going one more step than the other. This is a hall of mirrors, where worlds are multiplied, as it were. So, this is an easy route into deep cognitive debt, a bottomless pit of unending speculations. But conversation can short-circuit these imponderables – I can ask you what you think or feel; the exchange of thoughts gets us out of a hole that the theory of mind might bury us in. It also allows us to share plans in advance, exchange hunting tips and tricks, and keep track of an extended network without actually meeting everybody.Footnote 10 In short, it aids and abets the passing of information across generations, the essential property of culture. One of the extraordinary facts about conversation is that we seem to keep a running tally of what we have told to whom – only the inebriated, the child, or the senile are inept here. This implies that we ‘bank’ all the incidental information we are given, for example that yesterday my wife left her handbag somewhere, so when she says ‘I’ve found it’ I know exactly what she means. It is this background of information that makes conversational exchange work so well, and we never know what information we may need in the conversations ahead.Footnote 11

Another line of explanation for why we expend so much energy in conversation is known as the Machiavellian intelligence hypothesis.Footnote 12 The idea is that primates in general exhibit a level of intelligence that far exceeds what they need for practical or subsistence activities. Social intelligence has been forged, on this account, in fluid primate societies where forming alliances, achieving deception and generally manipulating others has been essential to reproductive success – so motivating at least a prototype form of theory of mind.Footnote 13 Married to Dunbar’s correlation with neocortex size and the exponential growth of ties in an enlarging network, the theory is intriguing. Many primate social groups, and certainly bonobo, chimpanzee, and traditional human societies, have a ‘fission/fusion’ structure, where groups are not fixed but vary in size and composition according to foraging or defensive needs. Separations weaken bonds, but re-encounters are an occasion to re-establish them, or indeed to refashion them in a new way. When we see a friend we haven’t seen in a while, we exchange enthusiastic greetings and spend time to rekindle the friendship. If an old acquaintance has become powerful, or has become a pariah, or perhaps a rival, then the social relationship needs readjusting. This suggests that one of the functions of conversation is handling the constant kind of readjustment that fission/fusion societies require. In what William Labov called ‘the perils of micro-analysis’,Footnote 14 those who have looked deeply at conversational conduct have noted how, through an analytical lens, a seemingly friendly exchange looks more like a bout of martial arts – easy sequences of ego boosts and pricks, praises, teases, and criticisms. The mechanisms here are quite fascinating, and are the subject of Section 5.3. The theory of Machiavellian intelligence, however, based essentially on competition rather than cooperation, stands in contrast to ideas that theory of mind is basically motivated by the needs and benefits of joint action, an alternative line of theorizing advocated by Michael Tomasello and discussed in Section 3.1. In Tomasello’s view, it is cooperation versus competition that separates humans from our primate cousins.

5.2 What Do People Actually Talk about Anyway?

The founding father of sociology, Max Weber, proposed to the first meeting of the German Sociological Association in 1910 that the content analysis of newspapers would shed a great deal of light on contemporary society. However, despite the importance of content analysis in political science, search engines, and artificial intelligence (AI), very little of it has been done on ordinary talk. But obviously considerations about the functions of conversation might be illuminated by studies of what people actually talk about. Do they, for example, criticize others and warn their interlocutors about the unfair practices of others, as the ‘free-rider’ problem might suggest? If not, what are the main topics? Here, unfortunately, we are hampered by the very small number of studies documenting the topics of conversation in different cultures.

Even for English speakers, there are only a handful of studies, of which the best is probably one by Dunbar and associates, involving researchers taking notes in public places and assigning ongoing talk to fourteen topics on the spot.Footnote 15 Table 5.1 shows a grouping of these topics for a sub-sample, which makes clear that despite the expectation of talk about politics, the weather, sport, and the like, about two-thirds of informal UK English talk seems to be about social relationships and personal experiences. Critical gossip about absent third parties was very low in frequency and time.

Table 5.1 Main conversational topics in a sample from Dunbar, Marriott, & Duncan Reference Dunbar, Marriott and Duncan1997:240.

| Topics | Per cent of individual conversation time on each topic | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | Males | |||

| In female company | In mixed company | In male company | In mixed company | |

| Personal experiences | 30.5 | 34.3 | 18.8 | 32.9 |

| Personal social/emotional issues | 32.9 | 21.5 | 23.7 | 33.4 |

| Social/emotional issues of third parties | 23.9 | 37.5 | 40.6 | 18.5 |

| Gossip critical of third parties | 6.6 | 0.6 | 1.8 | 6.5 |

| Advice given or requested | 0 | 0 | 9.9 | 3.2 |

| Hypothetical social situations | 6.1 | 6.1 | 5.2 | 5.6 |

| Total time devoted to social topics | 70.2% | 69.3 | 59.6 | 66.5 |

| Persons N = 30 | ||||

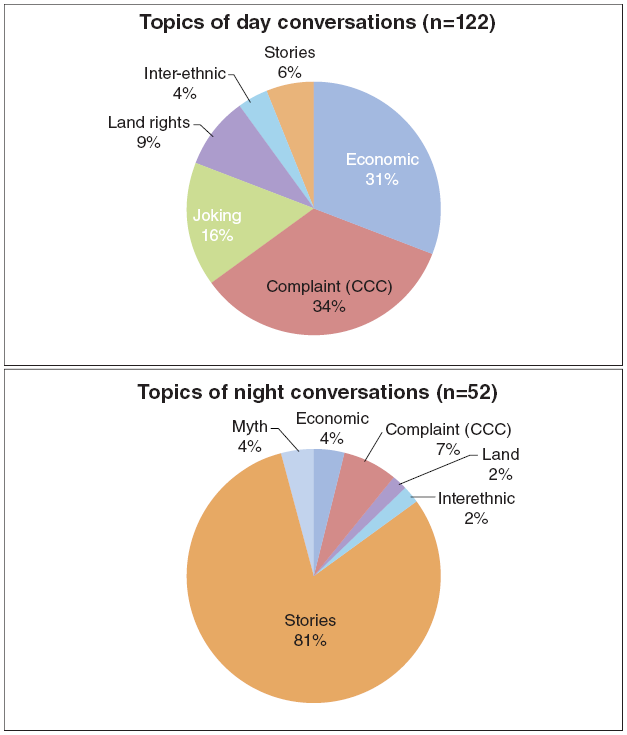

But what about other cultures? There is a paucity of data, but there is an interesting study about the topics of conversation among !Kung bushmen by the anthropologist Polly Wiessner. The !Kung were traditionally hunter-gatherers, and thus representative of the kind of small-scale societies characteristic of most of human prehistory. She found that there were quite different modes of conversation in the day and night, as shown in Figure 5.1.

Figure 5.1 Conversational topics among the !Kung (San foragers of the Kalahari) in the day (top) and at night around the fire (bottom) (from Wiessner Reference Wiessner2014). N indicates the number of conversations sampled (174 in total).

The largest category in daytime conversations in Figure 5.1 is composed of criticisms and complaints, nearly always about co-present parties, leading to sometimes heated debate. The 5 per cent of non-present parties criticized were ‘big shots’ being levelled by derogatory remarks. The category of joking covered the teasing and horseplay between age-mates, mostly youths (see Section 5.3 about teases). Together these topics cover half of the talk. The other main topics were economic (foraging plans, resource availability, hunting strategies, and technology). Night talk was very different, being given over to larger-scale issues, often encapsulated in stories about known people – for example long-range exchange partners, or how such-and-such an arranged marriage came about, and thus core social institutions.

To make up for the lack of comparative data, Penelope Brown and myself analysed four hours of conversation, sampling ten conversations from each of two other societies that we were familiar with, the Yélî Dnye speakers of Rossel Island, Papua New Guinea, and the Tzeltal Mayan people of Tenejapa, Chiapas, Mexico. For each society we had a target of 5,000 utterances and then assigned them to main topics. These are pilot (and unpublished) data, but they are concordant with our preconceptions and impressions (with the proviso, however, that the presence of the ethnographers may have given the interactions a more formal character). The results are given in Table 5.2. What is immediately self-evident is a very different distribution of topics between the two societies. Tenejapans find their own and others’ illnesses, the various curers and quacks available, fundamentally interesting; they visit the sick and enquire after them. Rossel Islanders have a culture of stiff upper lip when it comes to pain and suffering, and only death or cancer (taken to be a sign of sorcery) is a notable topic. Tenejapans participate in a wider market economy and grow cash crops, and money is of great interest to them (much of it squandered on counterfeit medicines), while Rossel Islanders have few chances to export crops, and no significant stores to spend money in. But they have traditional valuables or ‘shell money’ which is exchanged primarily only at marriages and funerals, and this tracks important social relationships, and often does not get properly handled or repaid (at least in their eyes), giving rise to conflicts. Finally, although both cultures have important festivals, for Rossel Islanders this is a major and frequent entertainment, put on whenever food supplies and leisure permit: this is where people meet, youths find their spouses, people show off singing skills and catch up with relatives. Criticisms and complaints surface under these categories but don’t seem to be a major focus.

Table 5.2 Topics of conversation in small samples from Tenejapa and Rossel Island

| Topic | Tenejapa (%) | Rossel Island (%) |

|---|---|---|

| illness | 51 | 2 |

| death | 5 | 6.5 |

| money | 37 | 4.5 |

| festivals | 7 | 43 |

| exchange system (‘shell money’) | 0 | 44 |

Altogether, these sources are scant data to give us a strong picture of the functions of conversation, except that they all agree that social relationships, and the events like illness, death, and marriage that affect them, are clearly prominent in all the samples. While direct quarrels arise in !Kung conversation as a means of catharsis in the absence of institutionalized legal proceedings, in the other two societies they are avoided and channelled into more formal procedures. It is true, then, that as far as we can tell, conversations everywhere turn to the thing that seems to matter most to humans – managing social relationships.

5.3 The Micro-politics of Conversation

There are many details of conversational conduct that show that, other things being equal, interactants exercise quite some caution with each other. Of course, sometimes individuals are not equal, and in extreme disparities of power – as with parents over small children – this caution may not be observed. Erving Goffman, a pioneer in the study of interaction, put it this way: in interaction we operate with the possibility of the ‘virtual offence’, the worst possible construal of what we are doing, and consequently take the effort to avoid that construal.Footnote 16 This is evident for example from apologies, which accompany such minor ‘infractions’ as a self-repair in conversation, or a phone call that turns out to be badly timed, or a call to a wrong number.Footnote 17 The elaborateness of apologies corresponds roughly to the perceived gravity of the infraction, with elaborate apologies (for example not coming to a meeting) being laced with explanations and excuses. The recipient of the alleged offence may absolve the offender with a ‘that’s alright’ or the like. Goffman likened all this to a mini judicial hearing, in which the explanations ask for mitigation of the offence.

An obvious area where this caution shows is in the proper use of address forms and titles, where these carry direct implications for the relationship of speaker and addressee. The principle is to use the most conservative, honorific form until dispensation has been received. Every culture has its own rules of address, and deviation may cause outrage, for example the use of first name in the American manner to an eminent German on minimal acquaintance.Footnote 18 Address forms are interesting enough that we return to them in Section 5.6.

A less obvious way perhaps in which social caution is evidenced is the way in which bad news is broached. First, there is the principle that the news should go in the proper order, first to the nearest and dearest (a principle internationally observed in the case of disaster announcements). Second, there are principles governing the manner in which it should be produced, by adumbrating it in advance, indicating reluctance to tell, and in the worst case letting the recipients themselves guess the content, as in this example:

<25> (from Terasaki Reference Terasaki1976:29)

D: ‘I-I-I had something terrible t’rtell you. So-’

R: ‘How terrible is it?’

D: ‘Uh, th- as worse it could be’

(0.8)

R: ‘W- y’mean Edna?’

D: ‘Uh yay.’

R: ‘Whad she do, die?’

D: ‘mm:hm’

Another example of the delicacy of news and opinions in conversation has been studied under the rubric of ‘epistemics’ – the degree to which specific participants in conversation have rights and expertise to the most authoritative opinion.Footnote 19 Many questions in English are delivered in declarative format with falling intonation (and some languages like Italian only have this format) – the only way that they can be recognized as questions is by virtue of who can be presumed to know what (as in You’re hungry). But the presumption of expertise, or lack of it, is potentially a fraught issue. Commenting on your addressee’s children, or querying a doctor’s diagnosis, or assessing a gardener’s work has to be done delicately if relationships are to be maintained. The degree to which one may be trespassing on another’s epistemic territory, thereby causing offence, is something that has to be constantly monitored.Footnote 20 On the view that one of the main functions of talk is to exchange information, then differential knowledge states is the very imbalance that drives it, and the accurate assessment of those states is essential to what and how information is delivered. The delicacy of that assessment is one of the things motivating the elaboration of linguistic form, as noted in Section 4.7 with respect to the multiple ways of phrasing questions.

Just as information is a potential asymmetry between participants, so is the degree to which one of the parties may benefit the most from the current interaction. For example, if I offer you advice, I take the view that am ‘giving’ you something; if I ask you for a pencil, it is clear you are the hoped-for benefactor and I am the beneficiary. These imbalances may also drive the motor of interaction, just as epistemic imbalances may do. And we may keep as careful a ledger of little debts and acts of benevolence as we do information that we have or haven’t shared.Footnote 21

In what follows we examine some of the central mechanisms involved in how relationships are juggled in the conduct of conversation.

5.4 ‘Face’ in Conversation

Penelope Brown and myself borrowed from Émile Durkheim, one of the founding fathers of anthropology and sociology, via Erving Goffman, the idea that, first, interactants treat other adults for the most part almost as if they are mini deities; and second, that, just as primitive rites consist either of anointing the idol (rituals of approach) or surrounding it with taboos (rituals of avoidance), so there are two main modalities for treating our fellow interactants.Footnote 22 Or as Durkheim put it: ‘The human personality is a sacred thing: one dare not violate it nor infringe its bounds, while at the same time the greatest good is in communion with others.’Footnote 23 By treating our fellow interactants in this way, we seek to oil the workings of our social worlds. Just as some deities need positive rituals (festivities, garlands, libations) while others require respect, fear and dread, and lack of molestation, so depending on our relationship to our interlocutor we perform positive or negative interactional rituals. You meet your long-lost friend with effusive greetings, but the monarch with formality and trepidation. We described this duality as the Janus-like nature of ‘face’ – the other’s self-esteem which needs to be massaged or respected according to circumstance. From this we derived a system of predictions for appropriate language use according both to the antecedent social relationship between speaker and addressee, and the degree to which the action being formulated in speech might endanger the other’s ‘face’. For example, if I want to ask my colleague May to lend me a book, I might gingerly enquire whether she is using it, and if not, could I borrow it for just a short time, so making it easy for her to find a reason to refuse. We looked at language use in three unrelated societies and languages and we came to the conclusion that our formulae worked reasonably well to predict the shape of polite and courteous language use. Since then there has been a veritable forest of further studies, with some cultural examples where our predictions don’t quite work, but overall a tendency for generalizations of this kind to work surprisingly well.Footnote 24

The formula we proposed was that the way an action (requesting, asking, telling, and so on) was phrased takes into account some measure of social distance (vertical or horizontal) and a measure of the degree of imposition (asking to borrow $100 would be more of an imposition than asking to borrow $1). The compound measure then determined choice between strategies: a low value might best be served by presuming familiarity and friendship (rituals of approach), but a high value might require indirection and the signalling of reluctance to impose (rituals of avoidance). So you might ask to borrow $5 from your room-mate by saying ‘Hey, lend me $5, Julie’, but when the sum was much larger might say ‘Would you by any chance have $50 I could borrow till next week, I’m completely skint’; and if you wanted to borrow the smaller sum of $5 from a colleague you don’t know very well, you might again use the second more elaborate formula. We called these politeness strategies, and we’ll return to them later in this chapter.

More recent approaches have been more contextual and interactional, or have recast the factors in terms of contingency (what it would take to bring about the desired state of affairs) and entitlement (what one has rights to),Footnote 25 but in many ways the essential insights still seem to be along the right lines. What we will retain in the sections below is the key idea that the nature of the social relationship interacts with the action being done to influence the way an action should be expressed if it is not to cause offence. A central presumption is that rational talk exchange would – other things being equal – be brief, efficient, and to the point (ideas associated with the philosopher Paul Grice and mentioned in Section 3.1). So, when it deviates, one suspects there is a reason. Indirection can then suggest hesitancy to intrude, while unnecessary bonhomie may predict an upcoming request for a favour. In short, it is a reasonable presumption that there will be no deviation from rational efficiency without motivation.Footnote 26 In this sort of way, when the smooth, efficient flow of talk seems a little obstructed, like a stream flowing over rocks, suspect that face considerations may be at play.

The notion of face that we invoked, following Goffman, was about self-esteem – it was crucially about the self, the individual. Some Asian scholars have reacted along the lines that this is yet another exponent of Western individualism, and that polite language use consists more in not disturbing the smooth flow of traditional interaction,Footnote 27 that is, following the local mores and conventions. Goffman also held that interaction rituals were conventional: ‘ritual concerns are patently dependent on cultural definition and can be expected to vary quite markedly from society to society’.Footnote 28 But it seems there is something much more systematic and cross-culturally similar at work. Another complaint has been that the notion of ‘face’ (as in ‘losing face’) is metaphorical or culture bound. Actually, though, there is something surprisingly material about the notion of ‘face’ as the following remarks will try to establish.

Friendly teases are an interesting genre. Teasing is an action not just shaped by ‘face’ considerations, but entirely motivated by relational (‘interactional ritual’) concerns – in this respect, teasing is more like greeting than requesting. But it has a curious character, consisting essentially of deflating the ‘face’ of a friend or peer in a ‘non-serious’ manner: it is a self-contradictory act, a playful provocation, an insult in jest, a stab with a rubber sword as it were.Footnote 29

Early ethnographers noted that in tribal societies there is often prescriptive joking and teasing between certain categories of kin. ‘The joking relationship is a peculiar combination of friendliness and antagonism …. There is pretense of hostility and a real friendliness’, as the anthropologist Radcliffe-Brown described it.Footnote 30 The systematic distribution of these relationships of ‘conjunctive disjunction’ in societies with lineages (or unilinear descent groups calculated through just the mother’s or the father’s line) has been fodder for kinship theorists like Lévi-Strauss, who posited what he called the ‘kinship atom’. The ‘kinship atom’ is the nuclear family – mother (wife), father (husband), son, daughter – together with the wife’s brother (or the children’s mother’s brother).Footnote 31 Following Radcliffe-Brown, Lévi-Strauss noted that in patrilineal societies where tracing through the father’s line is all-important for land, inheritance, and allegiance, the father is the authority figure, and the mother’s brother and his sons the friendly jokers. Where the authority is traced through the mother’s line, it is exercised by the mother’s brother, and the father’s sister’s husband becomes the joking partner (unfortunately, due to the preponderance of male ethnographers, we know less about the female perspective). It is the cross-cutting forces of close connection but disconnection by lineal descent that form the tensions expressed in this form of joking in tribal societies. Curious phenomena draw curious observers, and teasing has been much studied, but rarely with filmed data. Penelope Brown and I set out to remedy this, concentrating on peer interaction in three cultures.Footnote 32

Teases have a structure. They are usually occasioned by an expression of self-inflation, self-pity, or the like by the person who becomes the target. The tease itself may initially be delivered deadpan, but tends to have laughter syllables or a smile accompanying it and intonational cues to its character. But it is the reception that is particularly interesting: it has been noted that the response is typically a denial or explanation in a serious mode (which has been described as ‘po-faced’),Footnote 33 although at the same time often accompanied by a smile.Footnote 34

Here is an English example where R (rightmost participant in Figure 5.2) has been complaining that her other room-mates eat her food:

Figure 5.2 Hiding the face after a tease in English: Panel (1) corresponds to point (1) in Example <26> and Panel (2) corresponds to point (2).

This example has the classic tease character with R’s overdone outrage over purloined food being deflated by (leftmost participant) L’s deflationary tease (marked (1)), delivered with late laughter syllables. R responds with an acknowledgement and simultaneously hides her face, before responding with a ‘po-faced’ denial. But notice here the actual hiding of the face. Although the face may be averted rather than hidden, in all the cases examined the target’s face is turned away from the gaze of the teaser. Figure 5.3 provides another example where the protagonist on the left, L, is making mock apologies for making her friend on the right, R, watch second-rate movies, and in doing so likens R to a small child:

<27> Another English tease (from Rossi Corpus)

L: ‘and like I have to be pro-active to keep small chilDREN and YOU (.) entertai(hh)ned’ (laugh) ← (1)

R: (laugh, head down) ←(2)

R: ‘sometimes you say these things and they’re kind of hurtful’

((with laughter))

L: ‘Oh’ (laughter)

L: ‘But I love you to death, because (you?) actually do it, right’

B: ‘That’s true’

Figure 5.3 Hiding the face after another tease in English: panel (1) corresponds to point (1) in Example <27> and panel (2) corresponds to point (2).

This typical aversion of the face by the target of the tease was also found across cultures. Figure 5.4 shows the moment of teasing in an interaction on Rossel Island, Papua New Guinea, by leftmost participant L in panel (1), where L says he won’t repay the loan from the man on the right, R, followed by R’s averted face following the tease and the simultaneous collapse in mirth by L. In the local language, the embarrassed target of the tease is said to have ‘spoiled his face’.

Figure 5.4 Averting the face after a tease: tease delivery & receipt on Rossel Island, Papua New Guinea. Panel (1) moment of joke delivery, panel (2) receipt of joke.

Figure 5.5 shows a parallel case from a Mayan culture on the other side of the planet, a tease by the figure on the left, L, targeting the woman to the right. On receipt of the tease, R puts her hand in front of her face, while L bursts into laughter.

Figure 5.5 Obscuring the face: tease delivery & receipt in Tenejapa, Chiapas, Mexico. Panel (1) moment of joke delivery, panel (2) receipt of joke.

Why the hiding of the face? Close examination of film makes clear that it is because the recipient struggles to control the face at the moment of teasing. The faces of those teased typically show fleeting pain, surprise, and discomfort, before responding with a smile. In an experimental study of teasing among American college fraternity mates, facial muscles were coded for known expressive groups, and the targets of the tease showed embarrassment, fear, and pain, especially if they were new to the group.Footnote 35 Figure 5.6 shows the transitions into these pained expressions in two English speakers who were the targets of teases, where smiles give way to pained expressions.

Figure 5.6 Friendly teases are not without inflicted pain: transition of target’s face into pained expression at the moment of the tease in English.

We can conclude that ‘loss of face’ is not an entirely metaphorical notion at all! In Goffman’s dramatological language, we present our self in a mask appropriate to the role or part we are playing – when the mask falls, we are uncomfortably revealed in naked form.Footnote 36 We should not conclude from the fact that the targets often laugh that they have enjoyed the joke at their expense. As Darwin remarks ‘Laughter is frequently employed in a forced manner to conceal or mask some other state of mind, even anger. We often see persons laughing in order to conceal their shame or shyness.’Footnote 37

But what is the function of the tease? Teases are characteristic of peer groups, and it has been argued that they (or at least this friendly type) express solidarity. But how? They are often occasioned by one party claiming achievements or unusual suffering, and the tease serves to prick this illusion of specialness, and return the target to the close and equal standing the teaser claims. It is an attack on the other’s face, but in being flagged (by smiles, laughter, and intonation) as non-serious, it is partly disarmed. But the fact that the teaser judges that they can tease the target itself emphasizes the strength of the bonds between them. It is in effect a levelling device, in which the teaser gains momentary advantage. In the study of American fraternity students mentioned earlier, newer (lower-status) members teased their superiors in more gentle ways, and were harsher on their equals. But in either case, teasing seemed to bond successfully.

5.5 How to Be Polite: Some Simple Ways

Teasing is designed to embarrass the other at least slightly, and we’ve seen that persons teased tend to hide their face: their self-esteem is just a little wounded, making clear how we all invest importance in our own dignity, our own feelings of self-worth, and how potentially fragile this is. It is this fragility, both of the self and the other, that motivates the care we mostly take when interacting with others.

We’ve suggested that there are two kinds of interpersonal ritual; the rituals of approach and the rituals of avoidance. These give rise to what we’ve called ‘positive politeness’ and ‘negative politeness’. Positive politeness can be expressed positively, by expressing common ground and good fellowship; negative politeness is expressed by indicating reluctance to impinge, and the deference that might enjoin that. Although a lot of linguistic politeness is formulaic, the principles are generative, in the sense that they suggest indefinitely many ways of achieving the right effects. This is important, because it allows approaches to our fellows to be exactly and finely tuned for the occasion. Take for example the following telephone exchange between a junior colleague calling a more senior colleague:

<28> (from Levinson Reference Levinson1983:320; pauses in brackets in seconds)

Caller: ‘So I was wondering would you be in your office on Monday (0.2) by any chance?’

(2.0)

Caller: ‘Probably not’

Recipient: ‘Hmm yes=’

Caller: ‘=You would?’

Recipient: ‘Ya’

Caller: ‘So if we came by could you give us ten minutes of your time?’

Here the past tense of was wondering suggests a forlorn hope. The brief pause not being filled by the recipient’s assent, a doubtful by any chance is added by the caller. The longer two-second pause is taken by the caller to signify a negative answer – wrongly it later transpires – but a gap is taken as evidence for a negative response on the basis that such responses are only reluctantly delivered. Such a gap may also invite the original speaker to recast the request in a more acceptable manner. The whole is a study in ‘interactional pessimism’, a way of making it very easy for the recipient to escape the imposition. Note too how the subsequent Could you give us ten minutes of your time? emphasizes the cost to the recipient, although at the same time limiting the damage. This is typical English negative politeness, triggered here by deference to a higher status person when asking for a specific favour.Footnote 38 In its performance of reluctance to impose on the recipient, it also of course mildly flatters the other’s importance. This kind of strategic use of language to handle the sensibilities of interactants pervades conversational language. Many languages have honorifics or other conventional markers of deference and politeness (see Section 5.6) which may soak up some of the functions of the English elaborate interactional pessimism, but speakers of all languages are also likely to make use of similar expressions.Footnote 39

At the other informal extreme, where interactants are peers or kin, and the action has little face implications, requests may be simple and direct, for example, Salt (.) Tim please, said at the table.Footnote 40 The use of first names, kin terms, affectionate generic address forms like mate or buddy, jokes and teases (as we have seen) stress the common bonds. Hearing one’s own name is associated with a distinctive pattern of brain activation, related to self-presentation, it is in effect a kind of mini-grooming.Footnote 41

It is these subtleties of language use that offer a potent and at the same time delicate way of juggling social relationships among humans.

5.6 How to Construct a Social System

The chapter so far has shown how language use is diverted to serve social purposes. Not only do we talk mostly about social relationships, we actually use language to construct them. When we tease people, we assert that we are in the kind of close peer relationship that permits a level of controlled aggression. When we request things without indirections and apologies, we likewise assert equality (or in a different asymmetric pattern, power, as discussed in connection with Figures 5.8 and 5.9), just as we do when we reciprocally use first names or other informal address terms. When we respect, or violate, epistemic territories or claimed expertise, we make or remake the standing on which we interact. When we perform acts that benefit the other rather than the self (for example by offering help) we boost our own social standing. In myriad ways, the social world is there for us to create or recreate, make or unmake.

This is a view that has been energetically argued by the conversation analysts,Footnote 42 and it is certainly an important antidote to classical sociology and anthropology, where human actors are viewed as inhabiting a pre-existing social structure built by generations over millennia, responding to the impersonal forces of economics, power, and ecology. It is possible to have a spirited debate about this,Footnote 43 but it is probably not a coincidence that the conversation analysts’ view originates in California, where everyone can hope to become a millionaire. Europeans are likely to be more sceptical about the potent agency of individuals. But in the long run Emanuel Schegloff and his colleagues must be right: from beginnings in the smallest-scale societies of the Pleistocene, we have built complex civilizations by accretions of countless interactions between our fellows. The variety of social systems, the different sizes of human groups from scores to billions, the diverse ways of reckoning kin or contracting marriage, different tolerances for promiscuity or violence – the diversity rules out any tight innate constraints on social life.

So how do you build a complex social structure out of a simple primate fission/fusion grouping? What are the elemental building blocks? We have already met Lévi-Strauss’s kinship atom in Section 5.4 (the nuclear family with the wife’s brother). But we can now propose a different kind of structural atom for building societies. The atom involves three relationships. A relationship in anthropological theory is understood as a set of reciprocal rights and duties: a father for example in many societies has the duty to protect and provide for an immature son, and the right to demand obedience; a son in turn has the right to expect provision from the father, and the duty to be obedient.Footnote 44 Think about a relationship then as arrows in both directions – what I owe to them, and what they owe to me. The three types of relationships of the social atom can then be thought of as follows:

1. the relationship between two close peers of equal standing

2. the relationship between two socially distant peers of equal standing

3. the relationship between two individuals where one is ranked higher than the other.

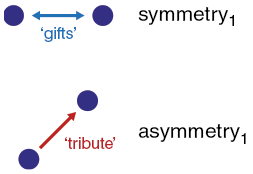

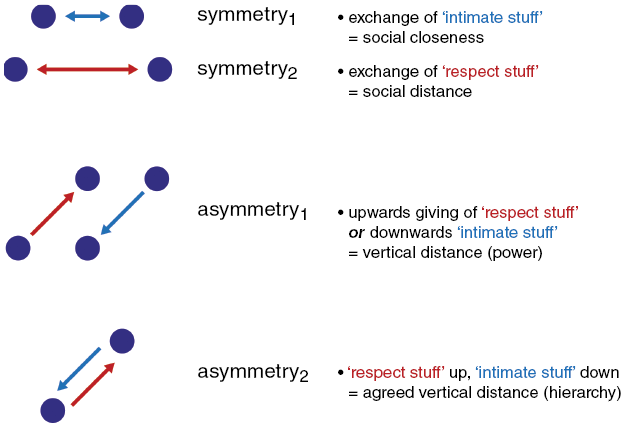

The metric for social distance or rank is locally determined and variable, but for example in the kinship domain same-sex siblings might be reckoned as close,Footnote 45 same-sex cousins as distant but equal, and parents ranked higher than children. Now we can introduce laws of exchange which govern these relationships.Footnote 46 As a first approximation consider the fundamental difference between symmetrical exchange and asymmetrical exchange. The first signifies equality, as in the exchange of gifts, the second signals inequality as in the giving of tribute, as in Figure 5.7.

Figure 5.7 Laws of exchange (first approximation): the symbolism of two-way exchanges (top, symmetry, signalling equality) and one-way exchanges (bottom, asymmetry, indicating hierarchy). The same goods have different valuation in symmetrical versus asymmetrical exchanges

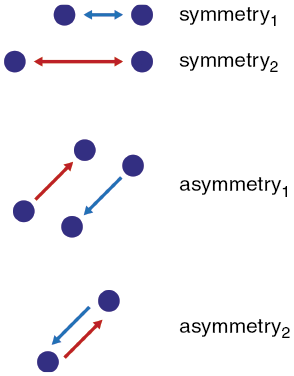

But now consider a more complex version, as in Figure 5.8, in which we take into account the nature of what is exchanged, distinguishing stuff that signals closeness from stuff that signals distance. Home-baked bread is a fine gift for the neighbours, but not a fit offering for a monarch. These laws of exchange express symbolic valuations associated with interaction patterns. There are a number of different patterns illustrated in the figure, and one mostly doesn’t find them all instantiated in a single system of exchange. Buying a round of drinks may express informal solidarity among friends, contrasting with the delayed exchange of formal dinner parties between newly introduced colleagues (the patterns in symmetry1 and symmetry2 respectively in Figure 5.8). I once attended the marriage of the daughter of an English squire, a landed gentleman. All his tenant farmers showed up in their Sunday best, bearing expensive wedding gifts, sets of bone china cups or fine cutlery or the like. And he fed them well and plied them with drink in return. This is the pattern of asymmetry2 – tribute going upwards, and intimate stuff (food) downwards, expressing the asymmetric nature of the relationship. There was no expected reciprocity, the squire would not be expected to attend the farmers’ marriages, which would be much more informal affairs. In a similar pattern, a Brahmin temple priest in India will dispense prasad, cooked food, to the lower-caste worshippers, and will be recompensed with coin in return.

Figure 5.8 Laws of exchange (generalized version with intimate versus distance signifiers). The lighter coloured line indicates ‘closeness, intimacy’; the darker coloured line indicates ‘distance’. Symmetry1 signals close peer relations, Symmetry2 signals distant peer relations. Asymmetry1 and Asymmetry2 differ only in whether there is no necessary exchange, as in the first, or there is two-way exchange, as in the second.

One domain where the full pattern in Figure 5.8 is displayed is in linguistic interaction. A simple example is the traditional use of first names versus titles plus last names in the English-speaking institutional world. At least in the recent past, the exchange of first names betokened familiarity and closeness, the reciprocal exchange of titles plus last names represented equal formality and distance, while the asymmetrical use of title-plus-last-name upwards and of first-name downwards (as between the secretary and the boss, or student and teacher) expressed a social asymmetry of rank. When Roger Brown and Marguerite Ford studied a Boston business in the 1960s this accurately described use, but US usage is more informal now, with a masquerade of universal equality.Footnote 47 Notice that if only one person uses a title, without reciprocation, as when the English shop assistant addresses you as ‘sir’ or ‘madam’, this signals the same rank differential (this is the leftmost Asymmetry1 in Figure 5.8).

The idea that social systems are based essentially on relationships formed on two or three dimensions, in particular horizontal social distance and vertical social distance, has a long antecedence both in the analysis of human and non-human primate societies.Footnote 48 On the view, sketched in Chapter 4, that the origin of language may owe something to importing spatial concepts into communication, it is not surprising that spatial concepts also structure our conceptualization of the social world – we talk after all, of close kin, distant cousins, high priests, and lowly beggars. Interestingly, the parts of our brain – including the hippocampus – that handle our spatial navigation also handle our social maps and networks in these two dimensions.Footnote 49

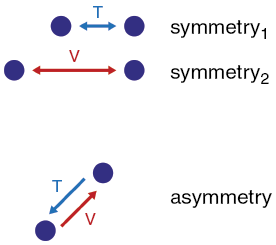

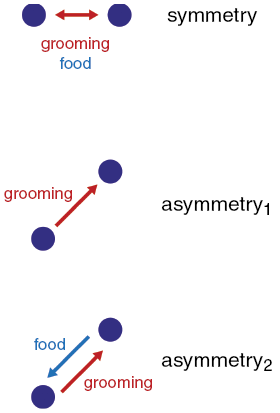

In trying to understand the underlying patterns in complexities of human social institutions, the use of titles and honorifics offer a useful way to trace the major patterns, a bit like using a tracer chemical in the bloodstream, or dye in a complex drain system. Linguistic honorifics come in many forms, but the simplest offer a choice between two pronouns, an intimate one as in French Tu or a formal one like French Vous. For language after language with such an opposition (and such languages can be found all over the world), the symbolism of the usage follows the patterns in Figure 5.9, where T stands for the intimate pronoun, V for the reserved one). The general pattern, first noted by Roger Brown and Albert Gilman, is that reciprocal exchange of the informal or T pronoun signifies social closeness (as when friends exchange Tu), the reciprocal exchange of the V (or formal) pronoun signifies social distance (as when business partners exchange Vous), and the asymmetric exchange of T one way and V the other signifies that the T giver ranks higher than the V giver (as when the boss addresses the secretary as Tu but expects Vous in return).

Figure 5.9 The symbolic significance of polite pronoun usage (after Brown & Gilman Reference Brown, Gilman and Sebeok1960). T labels the intimate pronoun (Tu in French, Du in German), V the formal pronoun (Vous in French, Sie in German). Note how the pronouns change their value in the different exchange contexts.

The thing to note about the pattern is that the very same items have different evaluations according to the exchange type: in the asymmetrical case, the intimate pronoun T (generalizing to all languages with this kind of opposition) no longer signals intimacy but rather rank superiority of the speaker, and likewise the V pronoun now no longer signals equal but respectful distance, but rather acknowledges the rank disparity. Why does this pattern within honorific systems seem to be universally applicable? Recollect the argument about ‘face’ and the two kinds of interaction ritual that we observe to protect it – in the positive rituals, we presume intimacy, as with the T pronoun, in the negative rituals we practice avoidance. The V pronouns are frequently just the normal plural pronouns, so when you use a plural pronoun to a singular person, you do two things – you allude to the addressee and their backers, their ‘side’ as it were, and you don’t nail them down in the same way; someone else in the addressee’s team might be minded to cooperate. By providing this ‘out’, the plural acknowledges the preference for avoidance, and because of this rational derivation, there is a worldwide tendency for plurality to signal deference, even if the usage is now entirely conventional – details have been recorded from some forty languages from all continents.Footnote 50 As for the asymmetric usage of T, it signals that the higher person has no need to respect the recipient, just as T does for very different reasons in the intimate symmetrical use.

Interestingly, there are systems of honorifics that are much more complex than these but follow the same sort of exchange rules, or principles of interpretation. South-East Asian languages (such as Japanese, Korean, Javanese) have politeness levels comprising elements like the T/V pronouns where reference is made to the honorable person’s things or kin, combined with alternate forms of verbs, nouns, affixes, and other expressions that simply indicate a style elevated for the particular addressee. For example, in Javanese the speaker must choose between nine levels composed from different such elements.Footnote 51 But despite their complexity, the significance or evaluation of the levels depends on the simple patterns of symmetrical versus asymmetrical use as in Figure 5.9.

Although the uses of honorific systems are often conventionally specified within particular kinds of social relationship, actual usage always shows more flexibility; in particular, usage may become more formal when the action being done is more of an imposition (in accordance with our politeness formula), and by changing the customary usage, relationships can also be momentarily or fundamentally changed.Footnote 52

Our interest in honorifics is simply that they illustrate very clearly the canonical patterns of exchange. In normal English usage, where honorifics are absent, the same functions are performed by more flexible language use bearing in mind the two principles of interaction ritual – a positive approach assuming familiarity, or a negative approach indicating reluctance to impose. In this regard, the elaborate indirection of polite English usage provides a significant hurdle for non-native speakers of English, just as the honorifics of Japanese do for non-native speakers of that language.

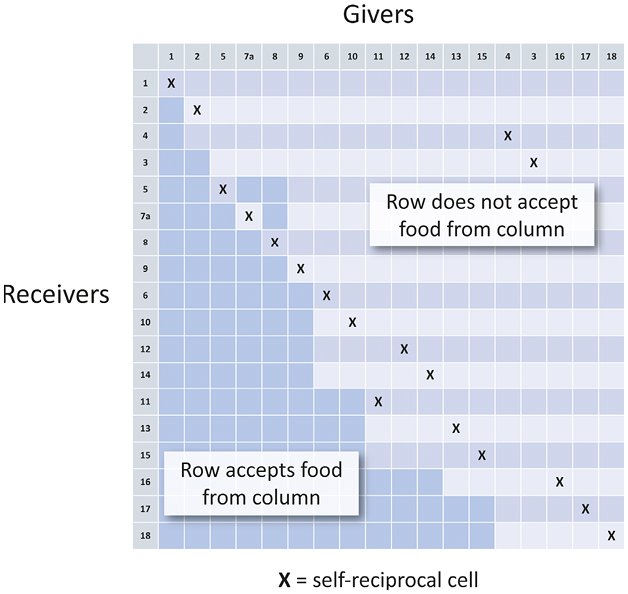

Now a very interesting thing about these patterns is that they are not restricted to language, as already hinted when introducing the laws of exchange. Again, particular conventional systems make this especially clear. Take for example the caste system in Southern India, which presumes a hierarchical ranking of caste groups in a local village. In this setting cooked food is exchanged according to the same sort of rules, namely the symmetrical exchange of cooked food signifies equality, the asymmetrical giving of cooked food in exchange for services indicates that the givers are superior. (In India, the exchange of food might occur both in informal domestic settings, and ritual ones, like temple feasts or marriages; further, castes are preoccupied with ritual purity, so a high caste individual will not eat food cooked by a lower caste which might be polluting, hence restaurants advertising high-caste Brahmin cooks are popular throughout South India.) If you map the matrix of symmetrical and asymmetrical exchange of honorifics onto say eighteen castes in a village, you will see there is a close isomorphism to the patterns of food exchange.Footnote 53 What on earth does a familiar T pronoun and cooked food have in common? Well, they are both ‘intimate stuff’. In a similar way, the symmetrical exchange of other non-intimate stuff or services may indicate equality but social distance, while the asymmetrical provision of services may indicate subservience. These services may themselves be symbolic, such as when members of lower castes will remove the dirty banana-leaf plates of higher castes after a feast, but not those of still-lower castes.Footnote 54 There is thus congruence between the honorific patterns in Figure 5.9 and the exchange of non-verbal material in Figure 5.10.

Figure 5.10 Generalized valuation of exchanges of ‘intimate stuff’ and ‘respect stuff’. Symmetrical exchange of ‘intimate stuff’ (such as prepared food) signals close equality, of ‘respect stuff’ (such as formal gifts) signals distal equality. Asymmetrical exchange of ‘respect stuff’ (including tributes, services) upwards and ‘intimate stuff’ downwards expresses hierarchy.

Note that in both cases, one can assume further systematic rules, specifically that these interpretations are transitive. So, if A gives a T pronoun to B, receiving V, and B gives a T to C, receiving V, then A will give a T to C and receive a V in exchange. Using these rules, we can construct hierarchies of indefinite depth. In the Indian village studied, this establishes a clear ranking over all eighteen castes, apart from a small cluster of allied castes numbered 5–8 which exchange food symmetrically, as shown in Figure 5.11. Food is exchanged in ritual contexts, for example marriage feasts or temple festivities. The figure is to be read this way: take for example, the PaNTaaram caste, a caste of temple priests, number 8 in the matrix. The column for 8 shows that members of this caste cannot give food to the first four castes (1–4 in the rows) – it will not be accepted. But the rest of the castes (5–18) will accept the food they have cooked. The exchanges both establish a hierarchy and symbolically mark it. In this way it is possible to construct a complex social system from the simple laws of exchange with their different evaluations.

Figure 5.11 Downward giving of cooked food establishes rank across eighteen castes in a Tamil village (from Levinson Reference Levinson and McGilvray1982, after Beck Reference Beck1972). Filled cells indicate that the caste in the row accepts food from the caste in the column; unfilled cells indicate that the castes in the rows will not accept food from the castes in the columns

If these patterns constitute the very atoms or building blocks of social systems, then we might expect to see something like them in our primate cousins. There seems to be some positive evidence for this. Recollect the view that there is some analogy between human conversation and primate grooming. Let us then consider the patterns of exchange in non-human primate grooming. What we expect to find is the pattern in Figure 5.12, with reciprocal grooming patterning just like the friendly use of T pronouns, ‘intimate stuff’ or food, but one-way grooming patterning like the V pronouns or ‘services’ in Figure 5.10 to indicate subservience. Many species of primates have clear hierarchical ranking of adults. In chimpanzees, male adults are so ranked relative to each other, usually assessed by primatologists by noting acts of aggression and submission. So, both symmetrical and asymmetrical exchanges of grooming are possible. And just like the pattern in the Indian village, it may be possible to compute the rank directly from the grooming behaviour.

Figure 5.12 Patterns of grooming/food exchanges in primates with hierarchies: grooming and food giving seems to pattern like the giving of ‘respect stuff’ and ‘intimate stuff’ in human societies as in Figure 5.10.

The findings from primate research are largely congruent with this prediction: it is a commonplace in primatology that mutual or symmetrical grooming takes place largely among peers, and that ‘grooming up the hierarchy’ is a well-attested practice, which may be the result of lower-ranking animals hoping to access food or social support.Footnote 55 It would even be possible to extract a social hierarchy of animals by observing the proportions of one-way grooming. Although these patterns are strikingly similar to the human rules of exchange, they are statistical tendencies, and do not have the crispness found in human interaction rituals, like the patterned exchange of honorifics – high- and low-ranking individuals may on occasion mutually groom, in a way that contrasts with the Indian example: high-caste and low-caste South Indians will never exchange services of the same kind.

In Chapter 4 we noted striking parallels in turn-taking behaviour shared across humans and other primates. Here we see another, albeit higher-order aspect of interaction organization, for which there are clear primate precursors to the human patterns. It is important to find these continuities if we are to understand the origins of human social life and communication systems. Darwin saw the parallels between human and animal expressions of the emotions, which are of course themselves fundamental parts of the interactional toolkit. If we are ever to formulate an adequate theory of the evolution of language it will be necessary to gather all these precursor elements together.

In this section we have sketched how it is possible to construct a complex social system out of elementary interactional units – patterns of dyadic exchange. Linguistic signals and arrangements for the use of language are symptomatic traces of more substantial, physical exchange systems and the ways in which these can build an economic and political structure based on the analogous patterns of dyadic exchange, carrying the same kinds of symbolic evaluations.

5.7 How to Construct Social Institutions

Turn-taking is a hallmark feature of informal human communication. We have detailed how it works in conversation, showing that the timing is a miracle of precision that can only be achieved by predicting how the other’s turn is going to end. We have shown that it has fundamental design advantages, by allowing rapid diagnosis of errors of interpretation and rapid means to correct them. We have noted that it emerges very early in human infancy, but is complex enough to not be fully mastered until late in middle childhood. It is even possible that the reason all languages have the simple clause or sentence as their basic structure is because this forms the canonical turn, the typical first part of an adjacency pair.

But interaction might have been organized differently, and proof of that is the existence of other special institutional types of talk exchange that social systems have invented. Unlike conversational turn-taking, which is interactional bedrock and universal, these special kinds of talk exchange are artificial, socially constructed systems, which differ across cultures. To construct these systems, canonical turn-taking is tweaked in systematic ways. For example, we can restrict all actions to question-answer pairs. Then we can assign all the questions to one party, and all the answers to another specific party – then we end up with something like cross-examination in a court of law. Or we could assign all the answers to one party, and all the questions to everybody else. Then we end up with something like a presidential press conference. Or we could assign all the questions to one party, and all the answers to everybody else, as in a classroom. But when we have many potential speakers we will need a system for choosing them – they could put up their hands, and the president or the teacher could choose the next speaker. Or the president or teacher could call on them one by one. Or there could be a pre-ordained list of questioners, as is often the case in press conferences. Or we could have a referee who chooses the next speaker from competing bids, as with a chairperson in the question-answer session after a seminar. The referee might also time limit the contributions, as in debate between presidential candidates. The possible designs are legion.Footnote 56

In the systems just described, what is tweaked is who can talk, in what order, and what kind of an action they may perform. These are all constraints on the normal freedom of conversational interaction. Conversations start in two circumstances: either from an ‘incipient state of talk’ as when we are reading newspapers together in the same common room, or, alternatively, when we meet or come together, in which case greetings are in order, followed by an exchange of ‘How are you?’ and then the conversation starts. In the latter case, such a conversation winds down when each party indicates they have no more to say by passing up a turn at talk; then, expressions of the intention to meet again soon may occur, followed by partings.Footnote 57 But for the more institutional and non-conversational arrangements like press conferences or classrooms, we can also limit the mechanisms for starting and ending the event in other ways: perhaps the meeting starts exactly at 2.00 pm regardless of who shows up, or perhaps an essential chairperson must be present, or perhaps a whole quorum is required before things can start. The event may be terminated by the clock (as with a seminar), or by a referee (as in a court of law). But the point is that all these special conditions are additional constraints slapped onto the organization derived from the basic conversational exchange.

There are yet other tweaks, of considerable interest in their own right. There may be special constraints on the type of language or register that must be employed, or who can be addressed, as when in UK Parliamentary debates the only overt possible addressee is the Speaker (or chair) of the House of Commons, and references to other speakers must be in the third-person form of ‘the right honorable member for Richmond’, even when the current speaker is answering a question posed by that honorable member. Goffman here pointed out differences in ‘footing’: I can speak for myself, or I can speak for another party as with a press spokesman or a legal advocate. I can appear to be addressing one party, but actually be addressing another as with the parliamentary procedure, or when a cross-examination in a court is really aimed at the jury.Footnote 58

It is in the context of these special institutional tweaks on speech exchange that special linguistic forms arise. For example, the form The witness is to come in now is designed for a target who is not the addressee – the addressee is meant to go to the target and say You are to go in now. More dramatically, speech actions can be made possible that depend entirely on special institutional arrangements, like declaring people guilty, or declaring a couple now married, or baptizing a baby ‘Sebastian’. Language is now empowered to make war or peace, make walking without a mask illegal, excommunicate sinners, bequeath fortunes, name mountains, and fire workers from jobs. The philosopher J. L. Austin called these speech acts ‘performatives’ (as in I hereby name this ship the Discovery), because they empower mere words to have fateful consequences in the world through special arrangements in the institutional world.Footnote 59

Consider the following specialized speech event from Rossel Island, Papua New Guinea. Ten days after a death, people gather at the village of the deceased for a mortuary ceremony, at which shell money and axe valuables will be given to the spouse of the deceased in particular. The main function though is to divine the sorcerer who finished off the poor victim. There are two main parties: the bereaved (B), and outsiders (O), with the rest as audience or overhearers. Any adult male member of a party can bid to speak – the bid is done by getting his group (B or O) to clap rhythmically. The loudest claps win a turn at speaking (the failed competing claps must then fade away). If the speaker represents the O group, the turn must be filled by a yey, a sorcery accusation in ‘veiled speech’, alluding to the identity of the sorcerer via metaphor and association. If the winning speaker represents group B, the turn must be filled by an account of the death that makes it seem normal and not supernatural, and with details about how the B party tried to protect the deceased, tried to find remedies, and so forth – for this is a defence against a possible sorcery accusation. Finally, an O speaker will give a particularly pithy and obscure yey, and a village elder will declare the event over. Rossel Islanders believe that if you are clever enough you will have detected the identity of the sorcerer, and vengeance will in time follow.Footnote 60

In contrast to the culturally specific institutions, there is one form of specialized speech exchange system that seems unexpectedly universal. It is the speech – a form where one person speaks for an extended time, the audience (often seated) have no rights to speak although they may heckle or cheer. The occasioning of the speech, the apportioning of airtime and the presence of umpires is culturally variable – but the fact that a single person holds forth to argue some case on an extended basis is not. This is the locus of oratory, and often a special high-flown register is employed (in Tamil for example, the language used will partly be in a grammatical form of a millennium before), and an introductory phrase of the kind ‘ladies and gentlemen’ signals its launch. It is found in the simplest societies – indeed in societies that have no organized political institutions other than those provided by kinship, it plays a critical role in establishing leadership and a course of action. I have watched the role it plays on Rossel Island, essentially a tribal society where most decisions are made locally in village meetings summoned by the blowing of a conch shell. Long and impassioned speeches will be countered with lengthy retorts, until as passions diminish some consensus arrives. The style is so vigorous, with raised voices and violent gestures, that outsiders can be forgiven for imagining that the islanders are about to come to blows – but this is simply the form of local oratory. In an exchange of such speeches, conflicts are settled with the additional aid of compensatory shell money transfers, land disputes resolved, emergency measures taken to handle famine, the despoiling of fishing grounds halted, and so forth. As a result, this is a culture of orators, and I have been both surprised and impressed by the ability of young people of both sexes to stand up and defend their actions with subtle arguments. This is how, throughout prehistory, we must have managed our political lives. And even now in polities that number their citizens in the millions, political leadership is won not only by ruthlessness, but also by persuasive oratory, able to reach the far corners of dominions by virtue of modern telecommunications. Despite the fact that we live in an era of dangerous populists who exploit oratory for political ends, there is surprisingly little modern science on how we fall both for the uplifting oratory of a Churchill, a Martin Luther King, or an Obama, and the rantings of a Hitler, a McCarthy, a Trump, or a Berlusconi. We still have to turn for the most part to texts written millennia ago, by classical writers like Cicero.Footnote 61 What is clear though is that it is not just the words, but the whole multimodal performance exuding confidence in a future course of action, which is what wins over audiences. What is also clear is that we need some vaccine against the uncritical acceptance of this stone-age method of persuasion – a gullibility that may be the indirect cost of the trust essential to cooperation.

To sum up: How cultures construct their institutional speech events is that, taking conversation as the default starting point, they systematically restrict the participation by constraining:

1. Who can talk to whom,

2. In what capacity they act (as spokesman, representative, bystander, passive addressee),

3. How the next speaker is selected (pre-selected as in judicial hearing, or selected by a chairperson, etc.),

4. What kind of format the turns must be in (questions in an interview, prescribed words in a ceremony, in a special language or register, etc.),

5. The time allotted to each turn and to the overall event,

6. Whether there is a referee or chairperson,

7. How the event is begun and brought to an end.

The very existence of these culture-specific forms of speech exchange remind us of how informal conversation contrasts, with its local contingencies, free participation, ability to handle all types of contributions, rapid turn-taking and its self-correcting repair systems. The other more institutional systems indicate clearly that things could be otherwise, pointing again to the remarkable universality of conversation.

Other species of course lack elaborate social institutions, the equivalent of courts, schools, government agencies, and the like. Such institutions involve a whole normative order missing from the animal world; community consensus around such arbitrary arrangements involves language, cooperation, political systems, and much else besides. But it is important to see that our institutions can be built out of interactional bedrock by tweaking parameters here and there, and that an interactional fundament is indeed shared partially with our primate cousins.

5.8 Interaction and the Lowered Aggression that Makes Cumulative Culture Possible

It is fairly self-evident that humans conduct most of their social lives through communicative interaction, rather than through other means like direct aggression, murder, and rape. Comparisons of levels of violence in humans and chimpanzees show that even in societies without effective state policing humans have rates of aggression two or three times less than apes. When communicative mediation fails though, weapons make humans more effective killers, and fatalities in traditional human groups and apes are similar.Footnote 62 The quantity of human aggression seems effectively tempered by the ritual constraints described in Section 5.4, and the ways in which these can be used to structure stable social relations, which can be stacked to build complex social systems as sketched in Section 5.6.

It is these stable social frameworks that make the cumulative nature of human culture possible, and that is not something that would come about directly from cooperative joint action, as some writers including Michael Tomasello have imagined. A flux of shifting alliances does not allow for a building of trust and is rather a condition for permanent civil war. The relative stability of human social systems is greatly aided by the ritual constraints we’ve detailed, which enjoin a wary politeness to normal human interaction between strangers. Our interactional rituals play a crucial role: as Sarah Blaffer Hrdy has put it, if you trapped 300 chimps who did not know each other on a plane for eight hours, not many would emerge alive. If among chimpanzees and other primates, hierarchy and rank are primarily established by aggression, in humans they can be established by manipulating the kind of symbolic means encoded in our laws of exchange or the subtle modulation of language in interaction.

This use of a symbolic means for preserving and adjusting social arrangements provides the relatively stable platform that allows the accumulation of cultural knowledge and skill. Language and conversational interaction play a fundamental role here. In the words of a recent sculpture in the Science Museum in London, WHAT KIND OF LIFE EXISTS WITHOUT LANGUAGE?Footnote 63 No science, no literature, no history, no bureaucracy, no deep cumulative knowledge. But all of this in turn rests upon interactional foundations.