“La Raison du Plus Fort…”

In his Reference Marin and Houle1988 book Portrait of the King, Louis Marin, a contemporary of Foucault and Bourdieu, analyzes the source of the King’s absolute power under the reign of Louis XIV (1662–1715). Drawing on Pascal’s commentaries, Marin asks the following questions: How does (brute) force become power and what role does discourse play in this transformation? What does the discourse of power look like? For this, Marin considers the following fable, published by Jean de la Fontaine, the well-known poet at Louis XIV’s court in Versailles, in his collection of fables (1668–1694) and used since then in every schoolbook in French public schools.

Like Aesop’s fables from which they are inspired, La Fontaine’s fables use animal protagonists to illustrate human foibles and follies, and the power struggles that ensue. For example, the fable of “The frog who wants to make herself as a big as an ox” and ends up inflating herself to death makes fun of people who want to be someone they are not.1 In “The fox and the crow,” the fox manipulates the vanity of the crow to make him lose the cheese he holds in his beak by persuading him to show what a lovely voice he has; it makes fun of those who listen to flattery.2 While in these two fables, the moral of the story comes at the end, the moral of “The wolf and the lamb” is given to us up front: “The reason of the more powerful is always the best/ We will show it presently on the following case.” Indeed, readers might not understand the moral of a story in which a wolf eats up a lamb. Isn’t it what wolves are wont to do? Where’s the problem?

2.1 The Reason of the More Powerful

The problem as stated by Marin is this: Why does the wolf need to argue with the lamb over more than twenty lines before he actually pounces on him and devours him? Why does he need to justify himself with moral arguments, find a reason to use the overwhelming physical superiority that he evidently has? Let’s look at how he does this.

It is made clear from the start that the wolf is hungry and wants to kill the lamb in order to still his hunger. But he starts by engaging the lamb in what amounts to a rational, judicial procedure in order to justify his action. First, he accuses him of temerity or impudence, that is, not only for muddying the water but for behaving as if he were as entitled as the wolf to drink from that stream, thus framing his behavior from the start in terms of symbolic power differential. By declaring the water of the stream his property (“my beverage”), the wolf makes the lamb’s crime a crime of lèse Majesté. The wolf adds insult to injury by using the derogatory second person pronoun Tu (“tu seras châtié”). The answer of the lamb addresses both accusations with unimpeachable deference and submission: physically the lamb cannot possibly muddy the wolf’s water since he is drinking downstream from him; symbolically, the lamb gives all the signs necessary to show himself inferior to his accuser “Sire… Votre Majesté [Your Majesty].” Combined with the second person plural form of the pronoun, the third person form of address is here the ultimate sign of respect from a subject to his sovereign or a servant to his master (see “Madame est servie” [Her ladyship is served]). Unimpressed by the lamb’s polite and rational arguments, the wolf brutally re-imposes his representation of things (“You are muddying it”), further using the insulting Tu form. His tactic from now on is going to seek to reverse the public perception of wolves and lambs by portraying himself as the victim, thus eliciting in the reader feelings of compassion that will attach them to him, not to the lamb.

If the first accusation had to do with an alleged attack against the wolf’s authority, the second has to do with his reputation (his symbolic self), as he accuses the lamb of badmouthing him in the past. The lamb responds again with impeccable factual logic: “I wasn’t yet born.” The third accusation shifts from blaming the message to blaming the messenger: “If it’s not you, then it’s your brother” and again the lamb’s response remains at the level of facts (“I don’t have a brother”). After these three false accusations, the wolf changes tactics. Broadening his grievance to the lamb’s social and cultural identity in a shepherd economy, the wolf moves from blaming the individual messenger to blaming the messenger’s family and clan (“you, your shepherds and your dogs”), all of whom he sees as threats to his royal absolute power. But having expanded the scope of his grievance, it becomes difficult for the wolf to justify his impending attack on a newborn lamb. Since the facts don’t provide him with the legitimation he seeks, he has to resort to a higher authority – On me l’a dit: il faut que je me venge [I have been told: I have to take revenge].

The colon is key here. The indeterminate pronoun “l’’” (it) in “On me l’a dit [I have been told it]” points anaphorically both backward and forward. Both “You are a curse, so I have been told (backward anaphora),” and “I’ve been told that I have to take revenge (forward anaphora)” – in both cases, Public Opinion and Reasons of State, attributed to an impersonal “On,” prevail. The King has to take revenge to save his honor, but he can also deflect responsibility onto his counselors and ministers.3 This action becomes a matter of national honor and national security. And he can always plausibly deny that his action was self-interested. Indeed, it is important to note that the wolf’s revenge is not a psychological sense of vindictiveness or thirst for payback; it is rather the reestablishment of a balance of power between the two parties, the shepherds and the wolves, and their respective reputation or honor. In La Fontaine’s fable, “On me l’a dit” becomes the “filter bubble” through which anything the lamb might say is heard and received. Having smeared the reputation of the lamb and discredited his family and his people over nineteen lines, the wolf’s discourse has undermined any objective facts the lamb might adduce. It has prepared us for line 20 that legitimizes the wolf’s killing of the lamb by placing the responsibility on the institution of the Monarchy itself. The dialogue was from the start clearly not about water drinking rights, but about the honor of the Monarchy as institution.

Thus the stated moral of the fable: “The reason of the more powerful is always the best” is less a prescriptive statement than a faithful description of the way that symbolic power functions. The powerful, says Marin, need reasons to legitimize their power.4 Brute force without justice can be contested, gratuitous violence can be criticized, disputed. But by using the discourse of justice, that is, by representing himself as an unjustly hounded victim, the wolf adds an imaginary layer to brute force, and thereby gains what is called “power.” Brute force needs to appropriate for itself the discourse of justice, to stand for justice and to be taken as judicially equitable. In order to do that, the wolf has to refrain from pouncing on the lamb immediately. He has to use language, that is, linguistic signs, to represent himself and act upon the imagination of both the lamb and the readers. The purpose of this representation is not to speak the truth, but to create a symbolic world in which his action (i.e., his killing of the lamb) will be legitimate. A moral world, that both the lamb and the readers will buy into by virtue of its axiological rhetoric.5

One might wonder why the lamb is portrayed as responding to the wolf’s accusations in this way, when he should know that any such response will be taken as an act of overt defiance. This lamb, despite his young age, sounds like a Cartesian product of the Renaissance. First addressing the wolf as “Your Majesty” and “Sire” shows that he knows his place in the social structure and has already learned with mother’s milk the art of flattery. Then, he sticks to the facts and his talking points, which shows him to be rational and logical. But his quick wit and logical repartees may be perceived as “throwing shade” on the wolf, that is, expressing subtle contempt for the wolf’s baseless accusations. His insistence on his innocence could be seen as making the wolf look like a fool. One could wonder whether La Fontaine himself, by cautioning his readers against the abuses of the King’s power, might not be reinforcing the absolute nature of that power under the motto: “All publicity is good publicity,” even for the killing of an innocent lamb. Certainly, the popularity that the fable has enjoyed among young public school children in France since the seventeenth century suggests that they accept as a fact of nature the reasons given by the powerful to justify their actions.6

Power can only be exercised with the complicity of those upon whom it is exercised. The lamb is complicit by engaging the wolf into a rational dialogue of truth, the reader is complicit by accepting the premise of the moral stated at the beginning. The power of both the wolf and the poet is exercised through the imagination – the representation, aroused by language, of what could happen, how brute force could be deployed, what destruction could be wreaked for anyone who dares challenge it. Some critics have noted that the outcome is all the more cruel because the dialogue has raised hopes that in the end the wolf might be persuaded by the lamb’s arguments. That this does not happen because the argument was made in bad faith makes the moral of the story all the more ambiguous. Are the reasons given by the more powerful wolf the best because they are good reasons or because he is the strongest, as in the English proverb “might makes right”? La Fontaine, living as he did at the court of Versailles at the height of Louis XIV’s reign, was not about to put the power of the sovereign in doubt. He himself admired the King and would have condemned those who believed that the King’s power was subject to logical and legal negotiation.7

2.2 From Reference to Representation: Saussure and Beyond

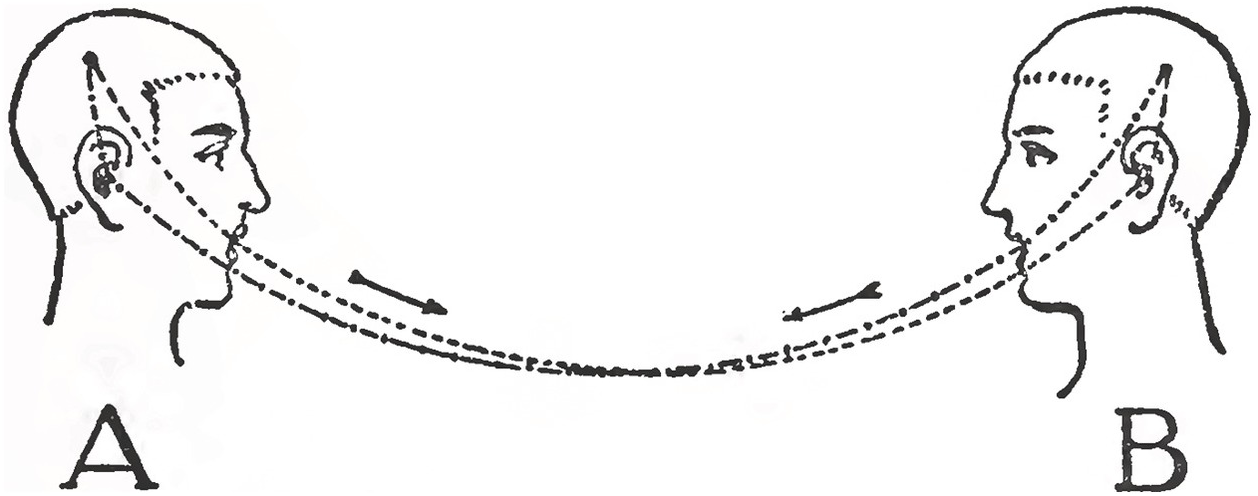

We have seen that language and other symbolic systems enable people not only to refer to things in the world but to represent them in our minds and to communicate these representations to others. Saussure schematized this in the form of the famous two heads connected by two dotted lines moving from A’s brain to A’s mouth, then from A’s mouth to B’s ear and on to B’s brain and vice versa (see Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1 Saussure’s two talking heads (Reference Saussure and Baskin1959:11)

What moves back and forth between A and B is not the sound-image nor the concept, which are both psychological entities, but their encoded symbolic representation. Speakers hope that the representation that reaches the other’s brain is the same as the representation that was in their own, but the process of representation is complex and ambiguous.

Upon rereading the fable of “The wolf and the lamb,” we can see how complex this process is. First, the wolf’s words are meant not only to refer to drinking water but to elicit a mental schema in the lamb’s mind – a mental schema of guilt and responsibility that is both psychological and affective. We can hear the cognitive disbelief and emotional indignation of the lamb in his response: “How could I do that? I was not yet born.” The legitimation of the wolf’s symbolic power requires the wolf to manipulate the lamb into believing he is guilty of muddying the water and thus make him complicit in his own death through shame.8 And so the readers are also asked to legitimize the reasoning of the powerful. Second, the wolf is portrayed as performing the power of the King towards his subjects. We are dealing here with a second meaning of “representation,” that of putting on a show, of staging or constructing a social reality through words. Not only does the wolf construct a dubious narrative about the lamb, but the poet himself constructs this narrative to edify or caution his readers. Third, the wolf manages to persuade the lamb not only to address him as one would a king (Your Majesty), but to see in him the representative or delegate of a higher power, be it God or the State (L’Etat c’est moi). That act of delegation is expressed by the ominous and vague pronoun “on” (“on me l’a dit”) that serves as the ultimate justification for the wolf’s action. I return to these three forms of representation in Sections 2.3–2.5.

The fact that even an absolute monarch like Louis XIV needs to provide legitimate reasons for his actions or else the people will not accept his authority is the ultimate moral of the story. Indeed, the exercise of symbolic power is not about objective truth but about whether one can get people to agree that it is true. The reason that the wolf and the lamb don’t agree on the meaning of the French verb “troubler” (as in troubler mon breuvage / to muddy my water) is that they each have different interests in that encounter. For the lamb, who is merely interested in quenching his thirst, troubler means concretely “to muddy the water.” The wolf, eager to assert his authority and to legitimize his impending killing, “to muddy the water” means to question his authority. Despite Saussure’s idealized speech situation, that sees the structural relation of the signifier troubler and the signified (troubled water) as the two sides of a sheet of paper, the fit between the two is far from perfect because of the different interests and motivations of the two speakers.

Beyond the gap between signifier and signified, the process of representation encounters also a gap between the concept in head A and the concept in head B. This gap is illustrated in Saussure’s schema by the two dotted lines that bridge the distance between the ear and the brain of each of the interlocutors, and between head A and head B. However hard the interlocutors try, that distance will remain. The impossibility of a perfect fit has been seen as an eternal absence that no act of communication can completely abolish. We have seen that symbols are open to multiple interpretations depending on how they are read, that is, which interpretant is chosen to disambiguate them. Literary critics like Derrida (Reference Derrida and Bass1978) talk about the meaning of a word as being constantly “deferred.” And Bakhtin showed eloquently that truth can only be gotten at indirectly through allegories, metaphors … and fables (see Chapter 9). The impossibility of perfect representation and yet the unavoidable necessity to try to close the gap lead to symbolic power struggles not only between kings and their subjects but between people in everyday life.

2.3 The Power of Symbolic Representation

Not all exchanges are as insidious as the one between the wolf and the lamb. In everyday life, we are constantly engaging in small exercises of symbolic power. We have seen (in the Introduction) how symbolic power is “the power to construct reality” and to have others recognize/accept this reality, that is, misrecognize its constructed nature. We don’t usually like to think that what we say about the world is anything else than what the world really is. How can a common greeting like “Nice weather today, eh?” construct the weather? Isn’t it just stating what is? We are ready to admit that the question is more than a statement of fact; that it is a greeting, a way of making contact (phatic communion), being friendly. But surely the weather is a fact that is independent of my talking about it?

Well – yes and no. For sure, I do not make the weather by talking about it. But by drawing someone’s attention to it, by passing judgment on it, by not saying that it rained the whole of last week but only saying that today is nice weather, as well as through my tone of voice, my facial expression and my body language, I give the weather a meaning, I influence the perception of my interlocutor as to its importance, as well as to the fact that I speak English, and that I use English like a native speaker. I am in a sense, albeit on a more modest scale than Bourdieu’s definition seems to suggest, displaying symbolic power, that is, the “power of constituting the given through utterances, of making people see and believe, of confirming or transforming the vision of the world and, thereby, action on the world” (see Introduction). The “eh?,” that seeks recognition, acknowledgement and complicity in my assessment of the weather could be seen as an exercise of symbolic power in constructing people’s representation of the social world by “mobilizing” their attention, their solicitude, their feelings and their belief that talking about the weather as a form of greeting is the most natural and legitimate thing to do. And if the encounter is between a man and a woman, the whole utterance could be understood as the power of the pick-up line.9

Or consider the following anecdote. My 2-year-old German grandson tried to get me to take him out for a walk by using the only two words he knew: “Schuhe anziehen” [put on your shoes]. But Oma didn’t seem to be paying attention, so he insisted with a plaintive voice: “Oma, Schuhe anziehen!” Oma then slipped on her shoes but didn’t budge. He got really upset, pulled at her coat and cried: “Schuhe anziehen, Oma!! Schuhe anziehen!!!” Clearly, the representation evoked in his mind by the words he was using (going for a walk) was not the same as the one Oma had upon hearing these words (putting on shoes). Of course she had understood what he meant, but had decided to respond to what he said, because she really didn’t want to go out. After a while, she decided to respond to his desire rather than to his words. She gave him a big hug and took him for a walk. Who would deny that already at that age a child knows how to engage in symbolic power struggles with adults?

Despite Saussure’s diagram and the folk belief that language is just the “conduit” for the exchange of information (Reddy Reference Reddy and Ortony1993), words and their representations do not travel, unscathed, from a mouth to an ear. They are affected along the way by emotions like desire, self-respect, pleasure or displeasure, by memories of former interactions and expectations of future ones. They are also the object of small or big power struggles between people with different interests like the one between Oma and her grandson. These subjective factors have objective effects and one recognizes their power indirectly from their effects. Oma didn’t realize the importance that the child attached to the phrase “Schuhe anziehen” before he started crying. In fact, he was only ventriloquating what he had often heard his mother say and was disconcerted to find out that it didn’t have the same effect on his grandmother. Even though his sentence was perfectly correct and comprehensible, his words failed to mobilize her, so he had to mobilize her through other means.

Precisely because we have to use linguistic, gestural, visual symbols to communicate with others, we are, with every utterance, playing with our and others’ symbolic representations of the social world. In the following, I return to the three meanings of the notion of symbolic representation we encountered in the analysis of La Fontaine’s fable in order to tease out their broader theoretical significance: representation as cognitive schema, as staged performance and as social and political ritual. In the following, I use the term “representation” both in the French sense used by Bourdieu (“mental representations” and social/cultural “objectified representations”) and in the English sense.10

2.4 Three Ways of Looking at Symbolic Representation

Representation as Mental/Bodily Schema – Lakoff, Johnson

The first meaning of representation is the one we usually associate with “image in the mind.” From a psycholinguistic perspective, we could say that “representation” is another word for epistemic and affective “schema,” a concept studied in language education mostly by scholars interested in the teaching of reading. In Cook’s words, “schemata are mental representations of typical instances […] used in discourse processing to predict and make sense of the particular instance which the discourse describes” (Cook Reference Cook1994:11). Cognitive science theory, however, has reminded us that the mind is “embodied” (Varela et al. Reference Varela, Thompson and Rosch1991) and that the idealized cognitive models (Lakoff Reference Lakoff1987: chapter 4) that we encountered in the previous chapter are not disembodied representations, but are very much anchored in the physical dimensions of our body or “body-in-mind” (Johnson Reference Johnson1987; see also Slobin Reference Slobin, Gumperz and Levinson1996).11 Representation in this first sense has, therefore, the following three characteristics:

Representation renders something which is absent present.

In the same manner as a photograph, a portrait or a statue render present someone absent, imagined or no longer there, so words give presence to distant or absent people or things. They can even substitute/be a metonymy or a metaphor for the real person (see condensation symbols in Chapter 1). In Schiller’s Wilhelm Tell, the hat of the governor prominently displayed on a staff in the town square had to be greeted by passers-by as it stood for or was used as a symbol of the governor himself. Similarly, some Christians cross themselves when walking by a church, thus re-present-ing, that is, making Christ and the cross “present again” through the symbol for Christianity.

Representation as embodied cognition.

As already mentioned, representation is an activity of the embodied mind and the learning of a first or a second language is also the learning of a particular relation to our body (see Kramsch Reference Kramsch2009a). As Bourdieu writes:

We learn bodily. The social order inscribes itself in bodies through this permanent confrontation [of our body and the world], which may be more or less dramatic but is always largely marked by affectivity and, more precisely, by affective transactions with the environment.

But what Bourdieu and cognitive scientists mean by body is more than just our head, hands and feet. It means at once:

– the space of the body (perceptions, sensations, emotions, feelings);

– the time of the body (memories, desires, anticipations, projections); and

– the reality of the body (actual/virtual reality, imagination, words made flesh, e.g., violent actions provoked by violent words).

Representation is both a construction of the embodied mind and a tool to manipulate other people’s representations through slogans, flags, emblems, badges, crosses and so on.

Representation organizes social reality.

Through the lexical and syntactic categories it provides, language as representation organizes reality into, say, animate and inanimate entities, insiders and outsiders, males and females, and classifies them, hierarchizes them, sequences them to yield a world that makes sense to us. Words give shape to inchoate thoughts. This is the principle behind the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis of language relativity that was mentioned in Chapter 1.12

In Women, Fire and Dangerous Things, George Lakoff uses Borges’ description of a fictional Chinese encyclopedia as a memorable example of the power of language users to organize reality. This encyclopedia, titled Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge, gives a taxonomy of the animal kingdom that can only make us laugh.

On those remote pages it is written that animals are divided into: (a) those that belong to the emperor, (b) embalmed ones, (c) those that are trained, (d) suckling pigs, (e) mermaids, (f) fabulous ones, (g) stray dogs, (h) those that are included in this classification, (i) those that tremble as if they were mad, (j) innumerable ones, (k) drawn with a very fine camel’s hair brush, (l) others, (m) those that have just broken a flower vase, (n) that resemble flies from a distance (Borges 1966, p.108).

Such a representation is disorienting. It produces a bodily reaction of helplessness precisely because our mind, our perceptions, our whole mind-and-body experience is thrown off. Our embodied mind expects the rationality that comes with alphabetical order, the hierarchy it implies, the subcategorizations of the term “animals” that it suggests – but all those expectations are flouted in this Chinese encyclopedia. Wedesperately struggle to find the logic behind the words and to fathom the intention of the writer. Lakoff comments: “Borges, of course, deals with the fantastic. [But] the fact is that people around the world categorize things in ways that both boggle the Western mind and stump Western linguists and anthropologists” (ibidem). Also among Westerners, scholars from different intellectual traditions expressed in different languages cut up reality in different ways, sometimes making it difficult to participate in international research projects even if everyone speaks English (Kramsch Reference Kramsch2009b; Zarate and Liddicoat Reference Zarate and Liddicoat2009).

Representation as Staged Performance – Goffman, Foucault

Closely related to representation as mental and embodied schema is representation as staged performance. In this sense, as Goffman has shown (Reference Goffman1959), the presentation of self in everyday life is both a presentation and a representation of how one wishes to be seen, exemplified today by the self-profiling on Facebook and other social media. The capacity to influence other people’s representations of oneself and the addiction to these representations caused by the need for constant public sanction are one example of the insidious and invisible symbolic power exercised by language and pictures in online media (see Chapters 7 and 8).13

As spectacle and performance, representation brings about what it represents (see Chapter 4). According to Bourdieu, representations are “performative statements which seek to bring about what they state, to restore at one and the same time the objective structures and the subjective relation to those structures” (Reference Bourdieu, Raymond and Adamson1991:225, my emphasis). For instance, talking about people’s regional or ethnic identity as displayed through such indices or criteria as language, dialect and accent, Bourdieu says:

[We should not] forget that, in social practice, these criteria are the object of mental representations, i.e., acts of perception and appreciation, of cognition and recognition, in which agents invest their interests and their presuppositions, and of objectified representations, in things (emblems, flags, badges, etc.) or acts, self-interested strategies of symbolic manipulation which aim at determining the (mental) representation that other people may form of these properties and their bearers. […] Struggles over ethnic or regional identity […] are a particular case of the different struggles over classifications, struggles over the monopoly of the power to make people see and believe, to get them to know and recognize, to impose the legitimate definition of the divisions of the social world and, thereby, to make and unmake groups.

Bourdieu clearly shows in this quote how mental/perceptual representations, coupled with acts and strategies of symbolic manipulation, can have performative effects in not only creating prejudice and discrimination, but in shaping social groups and prompting them to action.

In Discipline and Punish (1977/Reference Foucault and Sheridan1995), Michel Foucault gives a dramatic illustration of the power of these two forms of representation – as staged performance and as mental/bodily schema – through a graphic comparison of the public execution of Damiens the regicide in 1757, and the daily schedule of prisoners in the House for young offenders in Paris in 1837. On the one hand, we have the excruciating description of the torture and execution of Damiens, who attempted to kill Louis XV while he was travelling. This description or staged representation by the Gazette d’Amsterdam of April 1, 1757, is quoted by Foucault as follows:

On 2 March 1757, Damiens the regicide was condemned “to make amende honorable before the main door of the Church of Paris” where he was to be “taken and conveyed in a cart, wearing nothing but a shirt, holding a torch of burning wax weighing two pounds”; then, “in the said cart, to the Place de Grève, where, on a scaffold that will be erected there, the flesh will be torn from his breasts, arms, thighs and calves with red-hot pincers, his right hand, holding the knife with which he committed the said parricide, burnt with sulphur, and, on those places where the flesh will be torn away, poured molten lead, boiling oil, burning resin, wax and sulphur melted together and then his body drawn and quartered by four horses and his limbs and body consumed by fire, reduced to ashes and his ashes thrown to the winds.”

The detailed representation of the execution in the Amsterdam Gazette is meant to elicit and solidify in the minds of the readers a mental schema of overwhelming monarchical power, of “imbalance and excess” in the same manner as the ritual performance of Damiens’ execution in the public square was meant to act not as a deterrent, but as an edifying spectacle that would instruct the masses, build their spiritual strength and restore their faith in the King’s absolute power. As Damiens had disrupted the divine order of the cosmos by trying to kill the representative of God on earth, so was the ritual of punishment intended to make the world whole again. As Foucault writes: “The condemned man represents the symmetrical, inverted figure of the king” (p.29). The body of the condemned becomes the place where the vengeance of the sovereign is applied, the anchoring point for the manifestation of the King’s power.

Hence the symbolic meaning of each of the details given. By melting wax and sulfur together, the two ingredients of the King’s seal, and pouring the mixture into Damiens’ wounds, the sovereign puts his mark, brand, sign, royal seal on the body of the condemned. Yellow bee’s wax, yellow green sulfur, gray lead, yellow olive, dark brown resin are all natural elements that return the body to the earth that, according to the Bible, it comes from. Sulfur used to fumigate and disinfect is applied here as a ritual of purification. The musculature that holds the body together – breasts, thighs, calves – is taken apart. The body itself is drawn apart by four horses and quartered at the image of the four points of the compass, like the macrocosm. The dismembered body is then burned to ashes and the ashes scattered to the winds to ensure that it is not only not remembered but rendered invisible, nameless, erased altogether from human memory. The regicide’s punishment is a ceremonial celebration of the restoration of world order disturbed by the criminal act – a re-activation of monarchical power.

Foucault argues that such a spectacle of sovereign power had not only a mental representational, but also a performative effect on the masses. It taught them who they were, by making them into the subjects the King wanted them to be. In the same way as a theater play or a fable represents, that is, stages or performs human actions and their consequences, so did the “spectacle of the scaffold” hold up to the people, as in a mirror, “the affirmation of [monarchical] power and of its intrinsic superiority” (p.49) and of the role they as subjects had to play in that performance.

On the other hand, and by contrast, the Rules for the House of young prisoners in Paris published eighty years later by a certain Léon Faucher (1838 cited in Foucault Reference Foucault and Sheridan1995:6–7) made use of another kind of symbolic representation to punish and reeducate young offenders. No longer did the display of power impose itself directly through physical force and corporal punishment. Over the eighteenth century, brute force like the one displayed in Damiens’ execution increasingly failed to edify the masses and to legitimize the power of the King. People slowly turned away in disgust at the barbarity of the sentence. Foucault describes the change in the way power was exercised, namely from external physical destruction to internal self-discipline. By 1837, young offenders were being reeducated to the power of law and order by being held to a strict daily schedule of activities that represented and taught them self-discipline under strict surveillance. Here, for example, Art.17 and 18 of the Rules for the House of young prisoners in Paris.

Art.17 The prisoners’ day will begin at six in the morning in winter and at five in summer. They will work for nine hours a day throughout the year. Two hours a day will be devoted to instruction. Work and the day will end at nine o’clock in winter and at eight in summer.

Art.18 Rising. At the first drum-roll, the prisoners must rise and dress in silence, as the supervisor opens the cell doors. At the second drum-roll, they must be dressed and make their beds. At the third, they must line up and proceed to the chapel for morning prayer. There is a five-minute interval between each drum-roll.

Prayers, work, meals, school, bedtime were regulated hour by hour. The schedule, posted on the walls of the prison for all to see, was the public representation of a disciplinary voice that the prisoners were to make their own not only by performing its words, but by monitoring their progress as well. Slowly they would internalize the rules and exercise their own surveillance. The rigorous discipline imposed on criminals and delinquents was meant to bind criminals not through visual and mental images of physical retaliation and retribution, but through the reasoned performance of textual rules and regulations, controlled and monitored through panoptic observation and evaluation.

Representation as Delegation – Hanks, Bourdieu

The third meaning of representation is the one we generally use to denote the process of standing for someone else. A social group delegates someone to represent the group, people elect their representatives in government, political candidates stand for their constituencies, CEOs for their corporations, teachers for their academic institutions, parents for their families. We have seen how in La Fontaine’s fable the wolf’s ultimate argument relied on his claim to represent a higher Reason of State that forced him to take revenge for perceived wrongs.

Delegates exert vicarious power, they are the incarnation of a bigger, invisible authority that gives their words and actions legitimacy. One could say that any member of a language community stands for the community that invisibly monitors the communicative competence of its members, that is, what it is feasible, appropriate and systemically possible to say, and what is in fact done with this language (Hymes Reference Hymes, Ammon, Dittmar and Mattheier1987:224). The symbolic power of an individual is always a delegated power exercised invisibly by institutions, even though that power is constantly contested by individuals who, like the old man in the Bichsel story (Chapter 1), try and push its boundaries.

Representatives not only stand for, they also speak for, entities that are larger than the individual. Although we don’t tend to think of it that way, as speakers we wield symbolic power by virtue of using communicative practices usually associated with representation as delegation. In the following paragraphs, I look at four of these practices: vicarious speech, hurled speech, reported speech and oracle effects.

Vicarious speech. In many instances of everyday life, speakers speak for others, and depending on the context, this can be accepted as normal or seen as offensive. When a teacher says to her 6-year old students: “Let us be quiet now,” this is understood as totally appropriate, but if she says it to 22-year-old undergraduates, it might be understood as condescending. When a mother addresses her infant in a high-pitched voice, “Does she wants her milk now?”, she is using motherese to give voice to an infant who cannot yet speak; it is heard as a legitimate exercise of motherly solicitude. But when a man responds to a female colleague who complains about being treated unfairly at work: “There she goes again!” in the presence of other male friends, the use of the third person could be perceived by the woman as offensive, for he is not directly addressing her but indirectly putting her down by addressing his male friends about her. This is the reason why such speech is sometimes presented as a teasing (“I was only joking”), rather than an insulting strategy, thus allowing the participants to save face while providing the speaker with an alibi (see Chapter 4). This is also why in some families children are taught never to talk about someone in the third person in that person’s presence. This kind of communicative practice has been studied by linguistic anthropologists as a form of hurled speech.

Hurled speech. William Hanks (Hanks Reference Hanks1996:259–265) has studied “hurled speech” as discourse between two parties that Hanks calls “the instigator” and “the pivot,” performed within earshot of a third party that he calls “the target.” Like gossip, such discourse is usually meant to denigrate the target through speech that, albeit directly addressed to the pivot, is indirectly “thrown at” the target, who is meant to overhear it. Thus, for example, two women at the market are engaged in gossip face to face, when the target comes into view. The instigator says to the pivot mockingly, in a loud voice that can also be overheard by any passer-by: “Wow! Where are you going? You’ve dressed yourself well” and the pivot answers: “Oh there’s someone I need to see!”, their subsequent laughter implying sexual wrongdoing. Hanks comments: “The attack is invasive of the target. It attempts to dominate the target by subordinating her to the accepted values of the group, values like family propriety, monogamy and muted attractiveness in daily public settings” (p.263). Once attacked the target can confront her attackers directly, but she risks physical confrontation or what may be seen as unseemly behavior for a woman; or she can ignore the attack, but this might backfire, leaving the audience to believe that she indeed has a lover at the market. But, if she is accompanied, she might in turn use her companion as a pivot to reciprocate in kind, for example by throwing back hurled speech at her attacker such as “The poor dog, it doesn’t see its own tail, it sees only the tail of others” (p.264).14

Speech and thought (re)presentation. Discourse analysts have identified various ways in which speakers manipulate the speech of others and thereby exercise various degrees of symbolic control over them. This has been seen in terms of narrator’s representation of speech or action as an indicator of narrator control. For example, in Franz Kafka’s short story “Give it up!”, the narrator uses a not only vague, but narratively coercive way of describing a man seeking directions from a policeman on how to get to the station. “He spotted a policeman and asked him the way.” The policeman answers: “You are asking me the way?” and the man answers: “Yes, because I don’t know it.” When we look at the various ways the initial request could have been reported, we notice that the narrator chose the one that gave the man the least amount of symbolic power. Direct speech representation (“How do I get to the station?”) would have given the man maximal narrative agency. Indirect speech (“He asked him how he could get to the station”) or free indirect speech (“He approached the policeman. How could he get to the station?”) would have reduced the man’s narrative voice but retained the specificity of his request. By choosing to merely represent the speech act performed (“he asked him the way”), the narrator constrains the autonomy of the man and puts it squarely within his own narrative control. As Mick Short comments: “as we move from [the first to the last form of representation], the contribution of the character becomes more and more muted” (Short Reference Short1996:293).

Oracle effect. The fourth instance of representation as delegation is what Bourdieu calls “the oracle effect” of political or ecclesiastical speech. In the same way as the oracles of the Pythia in Delphi were interpreted by the priests as the words of Apollo himself, so are politicians today said to usurp the voice of the people to speak not only to and for the people, but in lieu of the people; and so do pastors, clergymen, and well-intended kindergarten teachers who use “we” rather than “I” to show their identification with the individuals in their care. The oracle effect is to give the impression that one is both the messenger and the interpreter of the message, that is, that one is not only a symbolic delegate of the people, but the people itself.

The oracle effect […] is what enables the authorized spokesperson to take his authority from the group which authorizes him in order to exercise recognized constraint, symbolic violence, on each of the isolated members of the group […] I am the group. I am an incarnation of the collective and, by virtue of that fact, I am the one who manipulates the group in the very name of the group.

Bourdieu calls this kind of representation “usurpatory ventriloquism” (p.211) or “legitimate imposture” (p.214). It would be wrong to take these negative terms as a condemnation of these practices. On the contrary, Bourdieu always seeks to show that symbolic power is the name of the social game that people who are the delegates of powerful entities like the Government, the Church or the Academy have to play, and not only corrupt politicians, untrustworthy clergymen or dishonest intellectuals.

Populist politicians are only an extreme case of representative delegates that don’t just speak for the people but actively construct the people in whose name they speak. Which means, in the case of representative democracy, the people are both the constituency they are speaking for and the audience they are speaking at, the latter containing potential recruits for the former.

In sum: Whether it be a mental embodied schema, a staged performance, or an act of delegation, symbolic representation is a view of the world that encapsulates our innermost desires, perceptions, memories and aspirations and is therefore prone to manipulation by self and others. In other words, it is what makes us into social actors in a symbolic power game that constitutes the realm of the “political” (le politique) in the broad sense of the term (see Introduction).

2.5 The Politics of Representation

The Bakhtin scholar and literary critic Michael Holquist reflects on the reasons why Bakhtin, as a Russian orthodox Christian and a Soviet communist, was so interested in parable and allegory. Faced with the “increasing gap between his own religious and metaphysical ideas and the Soviet government’s ever more militant insistence on adherence to Russian Communism” (Holquist Reference Holquist and Greenblatt1981:180), Bakhtin developed a theory that Holquist calls “dialogism” (Holquist Reference Holquist1990), which sees human utterances as being by definition a contest, a struggle between one’s voice and the voice of others. The words we use have been used by others in other places at other times, says Bakhtin; they carry with them a historical baggage that affects their meaning in the present.15 Dialogism is a theory of language that does not start with the linguistic sign, as in Saussure, but with the duality of self and other, indeed self in other and other in self in every word that we utter. In Holquist’s formulation: “I can appropriate meaning to my own purposes only by ventriloquating others” (Holquist Reference Holquist and Greenblatt1981:169).

But this ventriloquation is inherently conflictual, as “individual consciousness never fully replicates the structure of the society’s public values” (p.179). Faced with this fundamental contradiction built into the very fabric of language, every utterance seeks to make meaning indirectly not only in trying to understand events, but in trying to persuade others of our understanding. This gap between my representation of things and that of others is precisely the essence of politics understood as the power game of political interests (le politique; see Introduction). “If we begin by assuming that all representation must be indirect, that all utterance is ventriloquism, then it will be clear […] that difficulties do exist in moving from epistemology to persuasion. This is because difficulties exist in the very politics of any utterance, difficulties that at their most powerful exist in the politics of culture systems” (pp.181–182), that is, in the clashes between value systems.

By suggesting that all utterances are political, that is, represent conflictual value systems, Holquist and Bakhtin rejoin Bourdieu’s views on the power of symbolic representation. We can summarize these views as follows:

– In language, “relations of communication are always, inseparably, power relations which, in form and content, depend on the material or symbolic power accumulated by the agents (or institutions) involved in these relations” (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu, Raymond and Adamson1991:167).

– Language reproduces material/physical distinctions into symbolic distinctions.

– It imposes ways of representing and classifying persons, things and events and makes these classifications seem natural.

– It makes these representations stick through the power of suggestion.

– Because the power of suggestion appeals to our emotions as well as our cognition, the clash of representations is inevitably associated with moral values (Johnson Reference Johnson1993).

– Symbolic power strives to remain invisible and misrecognized as such.

– Ultimately, the clash of representations is part of the permanent struggle to define reality (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu, Raymond and Adamson1991:224).16

Suggestions for Further Reading

To further understand the gap between Saussure’s head A and head B, see Kress (Reference Kress1993) for his discussion of the arbitrary vs. motivated nature of the linguistic sign, and Derrida (Reference Derrida and Graff1977:18) for his notion of deferment (or différance). Goffman (Reference Goffman1959, Reference Goffman1967, Reference Goffman1981) is a must to understand the presentation and representation of self in everyday life. Berger and Luckman (Reference Berger and Luckman1966) is a classic for understanding representation as the social construction of reality. This social construction passes inevitably through the body and the embodied mind. Those interested in how cognition is intimately linked to (bodily) emotions, interests and desires should read Lakoff (Reference Lakoff1987), Johnson (Reference Johnson1987), Varela et al. (Reference Varela, Thompson and Rosch1991), Gumperz and Levinson (Reference Gumperz and Levinson1996), Kramsch (Reference Kramsch2009a). Very useful discourse analytic tools to interpret the representation of symbolic power in plays and prose can be found in Fowler (Reference Fowler1996), Short (Reference Short1996) and Simpson (Reference Simpson1997). Interpretation of the tu/vous distinction in La Fontaine’s fable will be greatly illuminated by reading the famous essay by Brown and Gilman (Reference Brown, Gilman and Sebeok1960) on the pronouns of power and solidarity.