Introduction

Policymakers and academics alike have invested much effort in comparing countries’ environmental performance (see, e.g., Jahn Reference Jahn1998, Reference Jahn2016; Wackernagel and Beyers Reference Wackernagel and Beyers2019; Boehm et al. Reference Boehm, Louise Jeffery, Judit Hecke, Fyson, Majid and Jaeger2022; Wolf et al. Reference Wolf, Emerson, Esty, de Sherbinin and Wendling2022; Guy et al. Reference Guy, Shears and Meckling2023). A wide range of concepts, theories, and empirical models that seek to describe and account for variation in climate policy outputs and outcomes have thus emerged (e.g., Congleton Reference Congleton1992; Bernauer and Koubi Reference Bernauer and Koubi2009; Gassebner et al. 2014; Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Böhmelt and Ward2017). Such research has progressed over the years from simple models concentrating on countries’ average income levels as a key determinant (see, e.g., Dasgupta et al. Reference Dasgupta, Laplante, Wang and Wheeler2002) to more nuanced explanations that examine the effects of social, economic, and political structures (see, e.g., Bättig and Bernauer Reference Bättig and Bernauer2009; Duit et al. Reference Duit, Feindt and Meadowcroft2016; Ward Reference Ward2006, Reference Ward2008; Ward and Cao Reference Ward and Cao2012).

We present research that builds on and adds to this literature by examining the welfare state–climate change nexus in lower-income countries (see also Rudra Reference Rudra2002, Reference Rudra2007; Yoon Reference Yoon2017). Specifically, we explore when and how the welfare state in lower-income societies could be helpful in addressing climate change more effectively, which would then be reflected in lower levels of CO2 emissions. This particular focus derives from several considerations. First, as suggested by prior research (e.g., Kerret and Shvartzvald Reference Kerret and Shvartzvald2012), welfare-state characteristics likely affect governments’ willingness and ability to pursue ambitious environmental action. However, these effects are not yet sufficiently theorized and empirically identified. Second, we study climate change, since decarbonizing economies induces costly policy interventions that likely have large distributional implications in society. This, in turn, requires mitigating measures, so as to make ambitious climate mitigation politically acceptable among the people. And welfare states could play a significant role in this respect. Finally, we focus on lower-income countries because, on average, they have made much less progress than higher-income countries in protecting their natural environment and are more vulnerable to further climatic changes, both locally and globally. To make things worse, lower-income countries are at risk of becoming pollution havens as environmental footprints of consumption are reallocated from the Global North to the Global South (see Presberger and Bernauer Reference Presberger and Bernauer2023). Moreover, their emissions account for a rapidly increasing share of global emissions, while variation in welfare state characteristics is particularly pronounced there. This makes lower-income countries very interesting for exploring whether and how welfare states could enable countries to embark on more effective climate mitigation policies.

Existing studies on the welfare state-environment nexus focus primarily on higher-income countries (Kerret and Shvartzvald Reference Kerret and Shvartzvald2012; see also Dryzek Reference Dryzek, Ian Gough, John Dryzek, Lengfeld, Markandya and Ortiz2008; Gough and Meadowcroft Reference Gough, Meadowcroft, Dryzek, Norgaard and Schlosberg2011; Meadowcroft Reference Meadowcroft, Barry and Eckersley2005; Gough Reference Gough2013, Reference Gough2016). For the aforementioned reasons, we think that it is important to extend this work to lower-income contexts. In addition, empirical findings on the welfare state–climate change nexus have remained inconclusive. That is, we know rather little about whether the relationship between the welfare state and climate policy outcomes is primarily synergistic, antagonistic, or insignificant – particularly so when it comes to lower-income countries, where ambitious environmental protection is urgently needed. Bernauer and Böhmelt (Reference Bernauer and Böhmelt2013), for instance, report only weak and inconsistent evidence that higher welfare spending is associated with superior climate policy outcomes. Koch and Fritz (Reference Koch and Fritz2014) find no evidence that more generous welfare states have progressed further in the direction of ecological modernization (see also Zimmerman and Graziano Reference Zimmermann and Graziano2020). And Sivonen and Kukkonen (Reference Sivonen and Kukkonen2021) show that public attitudes toward carbon taxes are more supportive if the welfare state is more generous and, thus, addresses socio-economic inequality more universally; however, their sample is limited to European, higher-income countries. We contend that one reason for these mixed findings may be that state capacity moderates the welfare state effect.

We seek to take the analysis of how the welfare state shapes climate policy outcomes in lower-income countries a significant step forward by arguing that there could be other factors that mediate effects. We claim that welfare states can be conducive to mitigating political opposition against climate policy through several mechanisms that, on aggregate, should make countries with more extensive welfare states more willing and able to limit their greenhouse gas emissions. However, we also argue that these effects are likely to be contingent on states having the capacity to deliver effective climate policy outcomes and welfare measures. This claim is somewhat analogous to Lim and Duit (Reference Lim and Duit2018) who contend that if the welfare state is large, a leftist executive can satisfy broad, but diffuse public support for environmental action without threatening its core support among industrial workers. We intend to further contribute to this study and others when introducing state capacity as a moderator between the welfare state and climate policy outcomes. State capacity is a key factor in addressing climate change (see Jahn Reference Jahn2016): for any government to address climate change effectively, it must have sufficient capacity to draft and implement corresponding laws and regulations. In light of this, state capacity relates to the government’s ability to implement its goals or policies (Cingolani Reference Cingolani2013). It concerns government performance to the extent that it comprises “material resources and organizational competencies internal to the state that exist independently of political decisions about how to deploy these capabilities” (Hanson and Sigman Reference Hanson and Sigman2021: 1496; see also Kaufmann and Kraay Reference Kaufmann and Kraay2008: 6).

We explore the role of state capacity as a moderating factor in the welfare state–climate policy outcome nexus. Ultimately, we contend that for lower-income countries to address climate change, there must be enough political support outside the government. Public support for climate policy outcomes, necessary to some extent even in autocracies, primarily depends on whether governmental action is perceived to be fair and, secondly, on whether it is perceived to be effective (Huber et al. Reference Huber, Wicki and Bernauer2020; Bergquist et al. Reference Bergquist, Nilsson, Harring and Jagers2022). If the welfare state is large enough and provides ample benefits, economic losers from climate policy outcomes can be at least partially compensated and protected. At the same time, public concerns about fairness may be allayed. In terms of effectiveness, the government must have the capacity to draft and effectively implement policies targeting climate outcomes such as lower CO2 emissions. As a result, the relationship between climate change and the welfare state is likely to be mediated by state capacity. Empirically, we examine this argument based on data for carbon emissions, social protection, and labor market regulations, as well as state capacity in 66 lower-income countries since 2005.

To this end, our research seeks to further our understanding of the differences across lower-income countries in CO2 emission levels, especially when examining joint effects of the welfare state and state capacity. Analyzing such combined effects, which is the key component of our research, is particularly important in lower-income contexts, where state capacity and the welfare state often differ considerably.Footnote 1 In high-income countries, in contrast, extensive welfare states go hand in hand with high state capacity. Against this background, we add to the theoretical and empirical literature on the welfare state–climate change nexus (e.g., Kerret and Shvartzvald Reference Kerret and Shvartzvald2012; Bernauer and Böhmelt Reference Bernauer and Böhmelt2013; Lim and Duit Reference Lim and Duit2018; Zimmerman and Graziano Reference Zimmermann and Graziano2020). We also contribute to research exploring the welfare state exclusively in lower-income countries (Rudra Reference Rudra2002, Reference Rudra2007; Yoon Reference Yoon2017), and to the knowledge of the determinants of effective climate policy outcomes (e.g., Gassebner et al. 2014; e.g., Congleton Reference Congleton1992; Bernauer and Koubi Reference Bernauer and Koubi2009; Jahn Reference Jahn2016; Guy et al. Reference Guy, Shears and Meckling2023).

Theoretical argument

Climate change policies and their outcomes typically impose differing costs on different parts of society, and individuals facing high costs are likely to oppose such measures. We thus start by outlining the direct and indirect ways in which the welfare state may compensate those experiencing high climate policy costs. To the extent such compensation is effective, we should observe more effective policy outcomes, i.e., lower emissions. We then go on to consider the fairness and effectiveness of policy outcomes. Climate policy can broadly be categorized as subsidizing, penalizing, or providing information in order to reduce carbon emissions and, more generally, greenhouse gas emissions. To the extent it is sufficiently ambitious to be effective, climate policy imposes costs on businesses, their workers, and society at large because it shifts economic activity away from carbon-intensive sectors or requires costly changes of production technology. For instance, as a result, farmers may have to pay more for fuel and fertilizers. In addition to costs to businesses and their workers, there are costs to consumers. For instance, taxes on fossil fuels push up energy prices. Universal welfare states provide relatively generous benefits not only to the poor but also to middle-class groups, while covering a wide range of risks to citizens wellbeing (Rudra Reference Rudra2007; Jacques and Noël Reference Jacques and Noël2018; Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1990). We argue that, in lower-income states, they can potentially help to compensate those incurring high costs, whether they be poorer or middle-class groups, while also addressing concerns about unfairness However, adequate capacity to implement policy is also necessary to overcome the concerns of “losers” and perceptions of unfairness This leads to the expectation that carbon emissions, the observable implication of effective climate policy, should be lower when there is both higher state capacity and a welfare state strong enough to address socio-economic inequality in less developed societies.

Compensating losers

Effectively addressing climate change is a function of various drivers. One of them pertains to leaders’ need to build and maintain a winning coalition in order to survive in power – whether or not the state concerned is a democracy (Bueno de Mesquita et al. Reference Bueno de Mesquita, Smith, Siverson and Morrow2005; Cao and Ward Reference Cao and Ward2015). Although climate policy and its outcomes generally create both “winners” and “losers,” when it comes to maintaining a winning coalition, individuals and groups that stand to lose are likely to be particularly important. Suppose that lowering carbon emissions is perceived as generating losses relative to the status-quo position for some individuals. In the face of losses, they would be willing to use more resources and take greater risks to maintain the status quo than they would to shift policy by the same amount in a way that improved their payoff (Kahneman & Tversky, Reference Kahneman and Tversky1979).

In democracies, a leader’s winning coalition approaches half the size of the electorate, depending on voting rules. Though it is generally smaller in autocracies than in democracies, nevertheless, its size varies widely and can approach the democratic figure (Bueno de Mesquita et al. Reference Bueno de Mesquita, Smith, Siverson and Morrow2005). If so, the support base of the autocrat may include non-elite groups in society. The logic of political survival implies that leaders provide more public goods with the size of their winning coalition because bribing supporters with private goods becomes relatively expensive compared to proving goods in joint supply that all benefit from (Bueno de Mesquita et al. Reference Bueno de Mesquita, Smith, Siverson and Morrow2005). The welfare state has important public good properties (Goodin and Le Grand Reference Goodin and Le Grand2018). Having said that, autocracies were among the earliest to develop welfare states, sometimes partly for strategic reasons, as in the case of Bismarck’s Germany.

If leaders in some political systems worry about losing support of key groups when seeking to address climate change, what role could the welfare state play? Welfare states vary in the policies they embody and in levels of provision. However, many provide direct compensation to losers, for example via income support or retraining for those who lose their jobs. Welfare states can also provide a safety net that helps to ensure that people’s basic needs for housing, food, and health are met. This support may be temporary when unemployment or other economic shocks hit, or it may be given over long periods, as in the case of pensions or family benefits. The welfare state can also have an indirect function (see Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1990; Korpi and Palme Reference Korpi and Palme1998; Goodin and le Grand Reference Goodin and Le Grand2018) due to its association with improved economic development and higher labor market flexibility (Rudra 2005; Haggard and Kaufman Reference Haggard and Kaufman2009; Jacques and Noël Reference Jacques and Noël2018). For one thing, this makes losers more likely able to find alternative employment in a growing economy with more job opportunities. State provision of education and health can be seen as part of the welfare state. Well-educated, healthy citizens are better able to weather economic shocks by changing jobs or consumption patterns.

Countries seek to mitigate and adapt to climate change in various ways (Fekete et al. Reference Fekete2021; IMF/OECD 2022). Mitigation action in the Global North and China (Teng and Wang Reference Teng and Wang2021), Brazil (Fraundorfer and Rabitz Reference Fraundorfer and Rabitz2020), or India (Dubash et al., Reference Dubash, Khosla, Kelkar and Lele2018) has received much attention given the importance of these states to climate change. Across lower-income countries, there is considerable diversity among the potential losers, and the poorest groups in society are not necessarily the only ones. To this end, lower-income countries’ governments seeking to pursue ambitious climate policy outcomes can affect employment both among those with relatively low incomes and among the better paid. For instance, as well as creating jobs, promoting renewables also threatens relatively high-paid workers in extractive industries such as mining and oil production that are important to many lower-income states.Footnote 2

While many lower-income countries adopted social policies to alleviate poverty in the 1990s, partially funded by international donors (Tillin and Duckett Reference Tillin and Duckett2017), it is by no means the case that the urban and rural poor are the only target groups. Lower-income countries, particularly in Latin America, which set up trade barriers to promote import substitution in the 1970s developed welfare states that provided cover for workers in protected sectors; and such policies continue even with greater economic openness, because interests are politically entrenched around them (Haggard and Kaufman Reference Haggard and Kaufman2009). Other countries, e.g., in Asia, have developed productivist rather than protective welfare states to provide the relatively skilled workers needed by export industries (Rudra Reference Rudra2007). China’s development of a welfare state since the 1980s was driven partly by the Communist Party’s fear of protest in rural areas and partly by the need to provide adequately educated and skilled workers for export industries (Haggard and Kaufman Reference Haggard and Kaufman2009). In many countries, there has been “layering” of policies whereby benefits have gradually been extended as groups have pushed for what others have already obtained (Haggard and Kaufman Reference Haggard and Kaufman2009).

Only the more general, more extensive, and universal welfare state in lower-income countries (Rudra Reference Rudra2007) is likely to be willing and able to offset negative labor market effects of stringent climate policy and its outcomes, besides doing more to help the poor. While it is not possible to provide a single account fitting all cases among such a diverse group as lower-income countries, it is safe to conclude that where the welfare state is general and universal it could protect losers from ambitious climate mitigation action, both among poor people and middle-income groups. On these grounds, especially since losers in leaders’ winning coalitions will be directly or indirectly compensated, we would expect a positive association between the welfare state and climate policy outcomes, notably lower emission levels.

Fairness concerns

Perceived fairness has been shown to be among the most important determinants of public acceptability of governments’ action to address climate change and to lower emissions (Drews and van den Bergh Reference Drews and Van den Bergh2016; Maestre-Andrés, Drews and Van den Bergh Reference Maestre-Andrés, Drews and Van den Bergh2019; Huber et al. Reference Huber, Wicki and Bernauer2020; Bergquist et al. Reference Bergquist, Nilsson, Harring and Jagers2022; Bechtel et al. Reference Bechtel, Scheve and van Lieshout2022). Fairness is a complex and contested concept. That said, in relation to climate change policies, fairness seems to concern “the extent that people, a process, or a distribution, are treated or implemented equally or according to criteria such as need or merit” (Bergquist et al. Reference Bergquist, Nilsson, Harring and Jagers2022: 236). Three aspects of fairness are important: fairness to self; fairness to others in society; and procedural fairness in developing and implementing the policy (Drews and van den Bergh Reference Drews and Van den Bergh2016). Subsidies, penalties, and information provision can all potentially raise concerns about fairness. Besides the need to raise taxes to fund them, subsidies can be seen as unfairly distributed if they largely benefit middle or even upper-class groups. For instance, subsidizing solar panels could create resentment among energy-poor people who cannot pay to install them, despite the subsidies. Carbon tax penalties are often partly passed on by business to consumers, which may be seen as unfair to those with low incomes and to those who have little opportunity to evade costs. If information campaigns do not reach poor rural people, they may be seen as unfair.

Ambitious climate policy commonly has important distributional consequences as (perceived) opportunity costs associated with them are likely to be higher for some and lower for other segments of society (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Hubacek, Feng, Wei and Liang2016). Because climate policy often adversely affects quite small groups, perceptions among the general population of fairness to losers is likely important. Distributional effects may thus create a conundrum for policymakers trying to satisfy public demand for effective climate change action while shielding parts of society from the opportunity costs of more stringent policy and its outcomes. The perceived distributional effects matter to judgments about fairness (Huber et al. Reference Huber, Wicki and Bernauer2020; Bergquist et al. Reference Bergquist, Nilsson, Harring and Jagers2022). Effective climate change mitigation, e.g., in the form of lowering emissions, that would otherwise be seen as unfair might be more acceptable if politically visible measures to shield vulnerable people against economic risks are in place. The welfare state can be one mechanism for providing such risk and cost shielding (Gough Reference Gough2016). Similar to what has been observed in relation to trade liberalization, the logic of compensation may also be at work in the environmental realm (Walter Reference Walter2010): the welfare state provides some protection, and climate policy outcomes generate increased demand for the welfare state and support for leaders who promise to provide it. The logic of social justice is likely to operate alongside – and to interact with – that of compensation: more generous welfare provision partially compensating losers directly or indirectly shielding them from future policy-outcome-related losses may make governmental action seem fairer to the public. Distributional concerns are often highlighted as part of the policy process by government agencies. If the welfare state is well-developed, it is more likely that agencies dealing with poverty and welfare will be able successfully to raise such concerns, often by mobilizing groups in civil society, helping to ensure that the policy process is seen as fair.

Importantly for our argument, lower-income countries’ governments seeking to reduce emissions can affect employment both among those with relatively low incomes and among the better paid. For instance, jobs in fossil-fuel extraction and automotive industries span these income groups. We expect a more strongly pronounced effect if the welfare state is more comprehensive or universal, even if concerns about fairness are stronger in relation to poorer people (see also Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1990; see also Korpi and Palme Reference Korpi and Palme1998; Goodin and Julian Le Grand 2018). Less generous, less extensive, and, thus, less universalistic welfare states would not necessarily protect middle-class voters from negative employment effects of better environmental policy outcomes (Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1990). In line with this reasoning, Sivonen and Kukkonen (Reference Sivonen and Kukkonen2021) find that attitudes toward carbon taxes are more supportive if the welfare state is more generous and, thus, addresses socio-economic inequality more universally. Indeed, universalistic welfare states spend more on transfers and services and reduce poverty and inequality (Jacques and Noël Reference Jacques and Noël2018). Only more extensive, more generous welfare states in developing countries (Rudra Reference Rudra2007) are likely to be willing and able to offset negative labor market effects of effectively addressing climate change, besides doing more to help the poor. Hence, they can effectively address concerns about fairness, and are more likely to be able to reduce opposition to climate policy and its outcomes.

Effectiveness concerns

Effectiveness is about “people’s beliefs that a policy can fulfill a specific aim,” and it has been shown to be another important determinant of support for climate change policies (Bergquist et al. Reference Bergquist, Nilsson, Harring and Jagers2022: 236). There are potential material, political (electoral), and other (e.g., reputational) costs from ineffective climate policy. Anticipated problems of this kind may deter the government from bringing measures forward in the first place. Bergquist et al. (Reference Bergquist, Nilsson, Harring and Jagers2022) and Huber et al. (Reference Huber, Wicki and Bernauer2020) note that perceived ineffectiveness of a policy lowers public support for it. For example, citizens are more willing to incur costs of climate change action if they are assured that – enforced by the state – other people also make sacrifices. Ineffective policies erode trust and also create perceptions of unfairness. Indeed, successful environmental collective action commonly depends on trust: support is higher if it can be assured that others will do the same. Kumlin and Rothstein (Reference Kumlin and Rothstein2005) argue here that contact with more generous welfare institutions builds the trust dimension of social capital. However, lower-income countries’ welfare-state institutions aiming at reducing socio-economic inequality generally may not be enough. We contend that there needs to be sufficient state capacity to facilitate the effective implementation of policies (see also Povitkina Reference Povitkina2018).

To avoid a tragedy of the commons through “mutual coercion, mutually agreed upon” (Hardin 1968; also see Usher Reference Usher and Usher2020), adequate state capacity is required. Without state capacity to enforce, citizens may not be assured that others will make sacrifices (see Hanson and Sigman Reference Hanson and Sigman2021; see also Kaufmann and Kraay Reference Kaufmann and Kraay2008; Centeno et al. Reference Centeno, Kohli and Yashar2017). Hence, mutual agreement will be hard to reach. Moreover, citizens also need to be assured that policy implementation will be effective, which requires high-quality bureaucracy as well as legislative discussion and oversight. Of course, state capacity is necessary to make effective use of welfare spending to reduce poverty and promote development. However, states with low capacity may also develop welfare states. Here, payments will often be corrupt or clientelist, though (Haggard and Kaufman Reference Haggard and Kaufman2009).

Summarizing our theoretical arguments, we expect climate policy outcomes, all else equal, to be more effective (i.e., lower CO2 emissions) in lower-income countries where a larger welfare state and a higher level of state capacity are both present. We thus hypothesize that the two factors operate synergistically: they help lower-income countries’ governments in their efforts to escape the conundrum associated with trying to impose costly new measures that also have strong distributional implications, while also seeking to prevent concerns about policy fairness and effectiveness from undermining support among key members of the winning coalition.

Research design

We analyze lower-income states’ information at the country level with repeated observations over time. The Quality of Government (QOG) Institute’s 2024 data (Teorell et al. Reference Teorell, Dahlberg, Holmberg, Rothstein, Khomenko and Svensson2024) provide the starting point for this time-series cross-sectional data set. Eventually, our sample comprises in total of 66 lower-income countries between 2005 and 2018. The states considered for our analysis are International Development Association (IDA) support eligible countries, i.e., lower-income ones. As countries may graduate from IDA support, and some do also re-enter IDA programs, the countries included in our analysis each year differ. A list of countries and years covered is given in the appendix. In the following, we describe the variables we employ, their operationalization and data sources, as well as the estimation procedures used.

Our dependent variable comprises information on carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions measured in metric tons per capita, as provided by the World Development Indicators. CO2 emissions, as captured by this data set, stem from the burning of fossil fuels and the manufacture of cement. They include carbon dioxide produced during consumption of solid, liquid, and gas fuels, and gas flaring. The World Development Indicators’ data were originally compiled by the World Resources Institute.

Alternative measures for our dependent variable such as climate-change-related policy outputs have the disadvantage that reliable data for them is largely restricted to developed countries, where there is little variation in the size of the welfare state and in state capacity. Focusing on carbon dioxide emissions allows us to address the issue of low variance in the key independent variables. In addition, CO2 emissions are directly tied to key economic activities such as industrial production, energy consumption, and international trade – all are central to our argument and are affected by climate policy. Moreover, it is ultimately emissions, rather than policy measures per se, that matter for the global climate system. Yet, another alternative outcome measure, i.e., total greenhouse gases, usually also includes emissions from biomass burning (such as forest fires), which does not fit our focus.Footnote 3

Given this dependent variable, we estimate two-way fixed effects in OLS regression models. The fixed effects are based on countries and years and, thus, control for unobserved time-invariant unit-level influences and any system-wide shocks that may affect each sample state in a similar way, respectively. We also include a lagged dependent variable in all estimations to address unit-specific temporal path dependencies. Following Keele and Kelly (2006: 188), we specify a regular “lagged dependent variable model,” where “the only lagged term on the right-hand side of the equation is the dependent variable.” As explained by Keele and Kelly (2006: 189), the lagged dependent variable captures the effects of the predictors also in the past (e.g., t-1, t-2, etc.), although the explanatory variables are introduced in a non-lagged fashion. In combination, this is a rather conservative research design, which allows us to identify with more precision the key factors determining better climate policy outcomes in developing countries, although the unit-fixed effects take out some of the variance the core explanatory variables might explain. We also correct the standard errors and cluster them at the country level. Finally, while the two-way fixed effects setup has many advantages, Imai and Kim (Reference Imai and Song Kim2021) question its use. We thus consider the robustness of our findings when omitting the fixed effects for countries and/or years, and when estimating a random-effects model. In the appendix, we consider several other estimation procedures.

The core component of our explanatory variables is an interaction comprising variables for state capacity and the welfare state. First, to operationalize state capacity, there are several different variables available, with different theoretical conceptual understandings and time coverage (see Hanson and Sigman Reference Hanson and Sigman2021). We use the Worldwide Governance Indicators’ (WGI) government-effectiveness item (see Kaufmann and Kraay Reference Kaufmann and Kraay2008; Centeno et al. Reference Centeno, Kohli and Yashar2017), which offers the largest sample for countries and years, while it is closest to our theoretical understanding as it “combines responses on the quality of public service provision, the quality of the bureaucracy, the competence of civil servants, the independence of the civil service from political pressures, and the credibility of the government’s commitment to policies. The main focus of this index is on ‘inputs’ required for the government to be able to produce and implement good policies and deliver public goods.” In our sample of lower-income states, the variable’s values range between -2.26 and 0.69. Here, Zimbabwe or the Democratic Republic of the Congo are among the countries with the lowest level of state capacity, while Ghana (0.085 in 2007), Vietnam (0.092 in 2015), or Rwanda (0.210 in 2017) have, among others, the highest sample scores.

Data on the welfare state are even less standardized than that for state capacity and more difficult to obtain for lower-income states (see Jacques and Noël Reference Jacques and Noël2018). With a view to maximizing comparability, to increase data availability, and to operationalize the theoretical concept of the more extensive welfare state in lower-income states as closely as possible, we opt for the World Bank’s Country Policy and Institutional Assessment (CPIA) social protection rating score. The “CPIA measures the extent to which a country’s policy and institutional framework supports sustainable growth and poverty reduction, and consequently the effective use of development assistance.” The CPIA score is not assigned to higher-income countries. Only lower-income states are coded, and their performance is assessed against a set of 16 criteria grouped into four clusters: economic management, structural policies, policies for social inclusion and equity, and public sector management and institutions. At first sight, only the third of these clusters directly relates to the welfare state. However, to capture potential for poverty reduction, the World Bank felt it necessary to include the other dimensions. It should also be noted that lower-income countries’ welfare states are often partially funded by development assistance and that the CPIA was designed to facilitate efficient allocation.Footnote 4 The final item theoretically ranges from 1 to 6 with higher values signifying more universal welfare-state protection, but it ranges between 1 and 4.5 in our sample. The measure is time-varying, i.e., states may improve or worsen their social protection over time. We log-transform it to account for its skewed distribution. Also, it is generally assumed that the marginal effect of increases in income on welfare falls as income rises. If so, we would also expect, in line with using a log-transformed variable, for the marginal effects of a more universalistic welfare state to fall as the compensation they provide rises. Zimbabwe and Myanmar are among those lower-income countries with the lowest CPIA score of 1 (log: 0) and 2 (log: 0.693), respectively. Myanmar, for example, only allocated 2.19 percent of its budget to the welfare state in 2013. Countries at the other end of the CPIA index such as Georgia in 2009 (CPIA score of 4.5, log: 1.504) have allocated almost 20 percent of the entire government spending to social protection – which is close to the levels of some higher-income countries such as Iceland or Cyprus (about 20–25 percent of total spending).

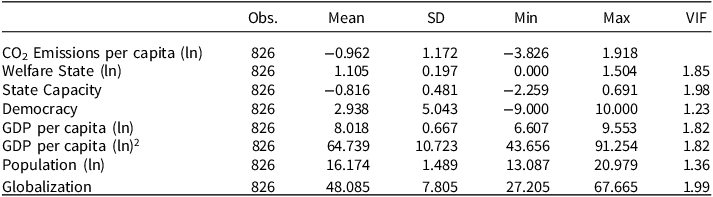

State Capacity and Welfare State (ln) are positively related to each other, but multicollinearity is unlikely to be a major challenge in our sample: the items’ variance inflation factors are well below the commonly used cut-off point of 5 (see Table 1 below). While interpreting interaction effects is not without difficulty (see Hainmueller et al. Reference Hainmueller, Mummolo and Xu2019; Brambor et al. Reference Brambor, Roberts Clark and Golder2006), we expect the term State Capacity * Welfare State (ln) to be negatively signed and statistically significant.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics

Notes: Interaction terms and variables for temporal correction are omitted; VIF stands for variance inflation factor.

We also control for a number of standard covariates in previous models focused on explaining climate policy outcomes (see, e.g., Fiorino Reference Fiorino2010; Jahn Reference Jahn2016; Lim and Duit Reference Lim and Duit2018; Povitkina Reference Povitkina2018). First, there is Democracy, which ranges between -9 (almost perfect autocracy) and 10 (perfect democracy) in our sample. Higher values stand for a more democratic polity. The item is taken from the Polity V data set, but included in the QOG data (Teorell et al. Reference Teorell, Dahlberg, Holmberg, Rothstein, Khomenko and Svensson2024). While democratic regimes vary in their institutional design and the empirical evidence for a positive influence differs across dependent variables, the common argument is that more democratic countries are more conducive to “greener” outcomes (Bättig and Bernauer Reference Bättig and Bernauer2009; Povitkina Reference Povitkina2018).

Second, there are income and population. Both variables are log-transformed and derived from the World Bank Development Indicators. More populous countries have an overall higher demand for energy and burning fossil fuels is necessary for meeting all citizens’ demands. According to the World Bank, population is defined as a country’s midyear total population, which counts all residents regardless of legal status or citizenship (except for refugees not permanently settled). States usually tend to “become rich first” before “cleaning up later” (Spilker Reference Spilker2013) – economic wealth is generally more important than environmental performance. The literature associates income with environmental protection also via the Environmental Kuznets Curve (e.g., Dasgupta et al. Reference Dasgupta, Laplante, Wang and Wheeler2002). GDP per capita (in constant 2017 international dollar) is defined as the gross domestic product (GDP) – the sum of gross value added by all resident producers in the economy plus any product taxes and minus any subsidies not included in the value of the products – divided by midyear population. We control for a non-monotonic impact by adding the squared term of income.

Our last control variable is Globalization, which is Dreher’s (2006) globalization index. A higher value of this variable signifies a greater embeddedness in the global political, economic, and social network. Here, lower-income states may have a stronger incentive to present themselves as attractive investment locations; or they could be subject to transnational influences pushing them to more effective policy outcomes considering their trading partners’ efforts (see Neumayer Reference Neumayer2002; Bechtel and Tosun Reference Bechtel and Tosun2009; Aklin Reference Aklin2016). Table 1 summarizes the descriptive statistics of the variables we have introduced in this section.

Empirical findings

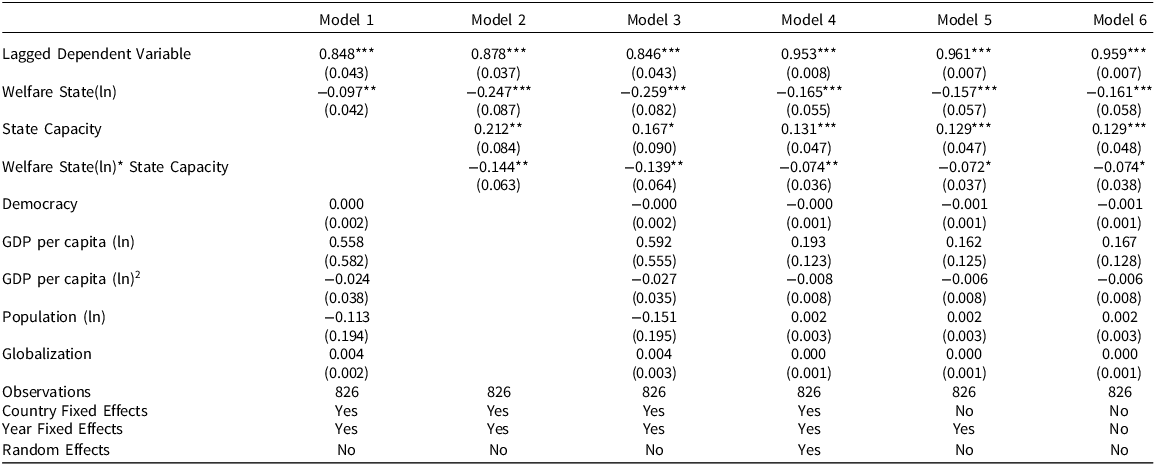

The empirical models are summarized in Table 2.Footnote 5 Models 1-3 are based on two-way fixed effects OLS regression. However, Model 1 leaves out State Capacity and its interaction with Welfare State (ln). In this estimation, we thus explore the impact of the welfare state only. In Model 2, we implement the interaction State Capacity * Welfare State (ln), but omit the control variables. Model 3 constitutes our main specification as we include the interaction of State Capacity and Welfare State (ln), while incorporating the control variables. Model 4 is a random effects model, while we leave out the country-fixed effects or country and year-fixed effects in Model 5 and Model 6, respectively. We complement the table with two graphs on substantive quantities of interest (Figures 1-2), which are based on Model 3.

Table 2. Empirical models – CO 2 emissions per capita (ln)

Notes: Table entries are regression coefficients; standard errors clustered on country in parentheses; constant, year fixed effects, and country fixed effects omitted from presentation.

* p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01 (two-tailed).

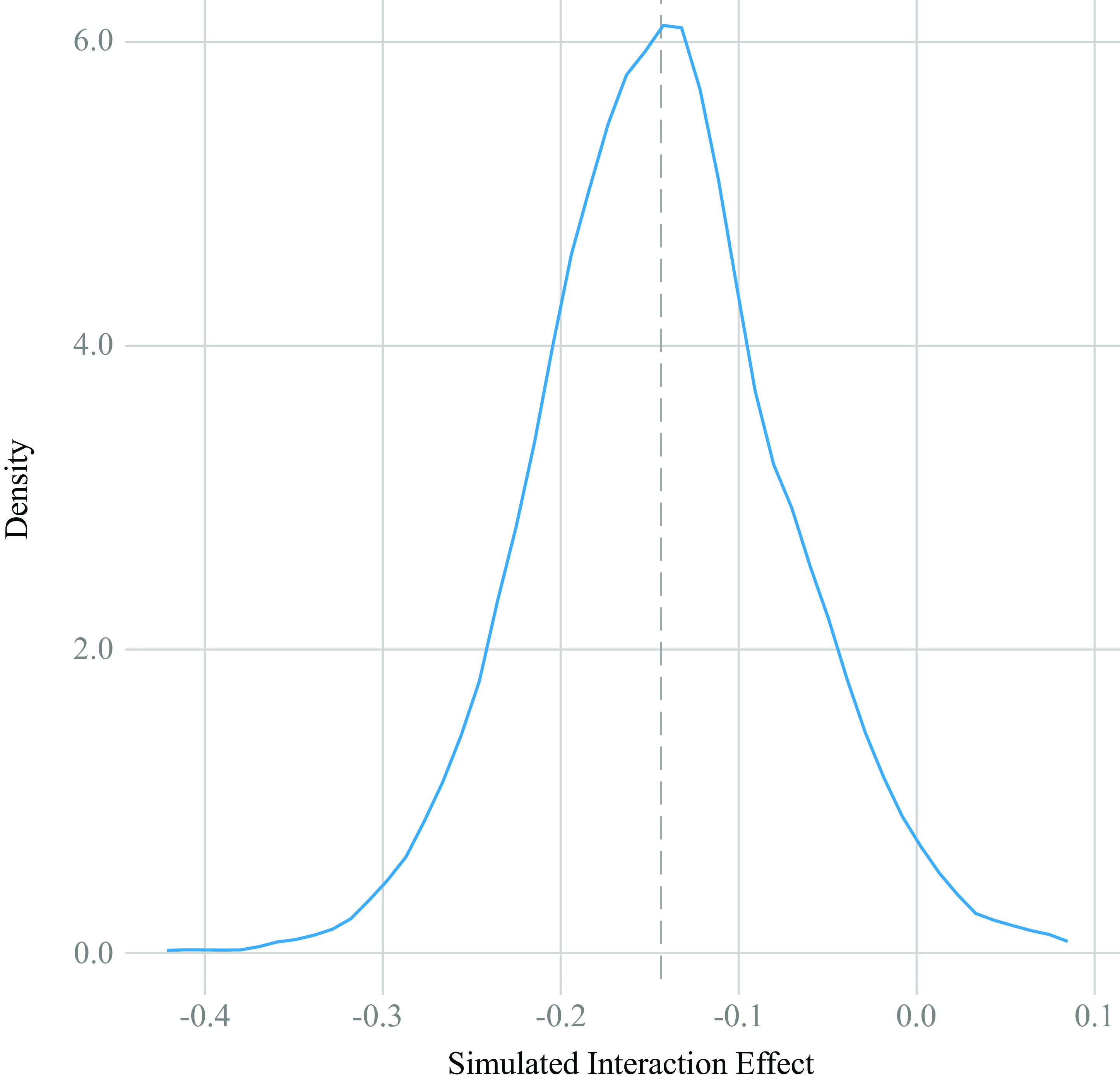

Figure 1. Simulated interaction effect. Notes: Graph displays distribution of simulated interaction effect in the form of average marginal effects (N = 1,000 simulations); dashed vertical line stands for mean value of interaction’s marginal effect (-0.144); graph based on Model 3.

Figure 2. Marginal effects at the mean of welfare state (ln). Notes: Graph displays marginal effects of Welfare State (ln) for given values of State Capacity; dashed lines stand for 95 percent confidence intervals; horizontal dotted line marks marginal effect of 0; rug plot at horizontal axis depicts distribution of State Capacity; graph based on Model 3.

Model 1 points to a negative impact of the welfare state in lower-income countries on emissions. We obtain a coefficient estimate of -0.097, which translates into a 1 percent decrease in emissions for every 10 percent increase in the welfare state. The estimate is statistically significant at the 5 percent level. Having said that, the direct test of our theory is the interaction term State Capacity * Welfare State (ln), which we expect to be negatively signed and statistically significant. And indeed, Table 2 shows that this is the case across Models 2-6. Models 2-3 can be directly compared with Model 1 as we use two-way fixed effects OLS regression in the first three estimations. The coefficient of the interaction term is estimated at -0.144 in Model 2 and -0.139 in Model 3. Both estimates are statistically significant, and they pertain to the impact of Welfare State (ln) on the climate policy outcome (CO2 emissions) variable when State Capacity is set to 1. The coefficient values in Models 2-3 translate into CO2 reductions of 1.4 percent (Model 2) and 1.3 percent (Model 3) for every 10-percent increase in a lower-income country’s welfare state. What is more, the size of the interaction term in Models 2-3 is larger than the coefficient estimate of Welfare State (ln) in Model 1 alone. This highlights that there is a synergetic effect between state capacity and the welfare state: while the welfare state on its own is likely linked to better climate policy outcomes in lower-income countries, the combined effect with state capacity is likely even more strongly pronounced. The estimates’ sizes in Models 4-6 cannot be directly compared with what we report for Models 1-3, but it is interesting that the interaction effect remains robust. Regardless of whether we calculate a random-effects model (Model 4), omit country-fixed effects (Model 5), or leave out country and year-fixed effects when using a simple OLS model (Model 6), the interaction term State Capacity * Welfare State (ln) remains negatively signed and statistically significant.

This negative effect of the interaction term in Table 2 suggests that more generous welfare states in lower-income countries are associated with better climate policy outcomes – but more strongly so if the state has a sufficient amount of capacity at its disposal. Figures 1-2 summarize substantive quantities of interest pertaining to the interaction effect and they also provide empirical support for our argument that state capacity can enhance the impact of the welfare state on lower carbon emissions. First, we simulate the marginal effect of the interaction term 1,000 times using the method in King et al. (Reference King, Tomz and Wittenberg2000). According to Figure 1, the simulations based on Model 3 give us an average marginal effect of the interaction term of -0.144. This estimate is virtually identical to the coefficient estimate in Model 3 above. Moreover, out of these 1,000 simulations, only about 1.9 percent of the simulations have a marginal-effect estimate larger than or equal to 0. Hence, there is robust evidence emphasizing that the relationship between the welfare state and CO2 emissions is, in fact, negative and statistically significant for less developed countries when there is sufficient state capacity to rely on.

Second, Figure 2 presents average marginal effects for Welfare State (ln) when setting State Capacity to specific values. For low levels of state capacity, the welfare state does not exert a significant or substantive impact. That being said, the influence changes when shifting the focus toward more capable state bureaucracies. Figure 2 shows that there is a negative marginal effect of Welfare State (ln) for high levels of state capacity, i.e., CO2 emissions per capita actually decrease. This stresses that, as argued in our theory, a lower-income country’s welfare state that is conducive to compensating losers of more climate-friendly regulations and state capacity that can implement and enforce policies are of crucial importance. This is only given for higher values of Welfare State (ln) as well as State Capacity.

To illustrate this relationship with some qualitative country examples, consider, e.g., Ghana in 2015-2016. Over the course of this time period, Ghana improved its state capacity slightly, while its CPIA social protection rating remained constant at 4. Over that time period, CO2 emissions (in metric tons per capita) fell from 0.496 to 0.492. Another example is Haiti, which scores low on both state capacity (between -2.170 and -1.297 in 2005–2018) and the welfare state (CPIA score of 2-2.5 in 2005–2018). During our observation period, CO2 emissions (in metric tons per capita) increased from 0.187 in 2005 to 0.299 in 2018, which is consistent with our argument.

In the appendix, we provide additional analyses to assess the robustness of our main finding using different estimation procedures, variable specifications, as well as variables included. First, Hainmueller et al. (Reference Hainmueller, Mummolo and Xu2019) remind us that multiplicative interaction models are based on two crucial requirements. On one hand, there must be a sufficient amount of “common support” to reliably compute the conditional marginal effects, i.e., cases for which the values of the moderating variable are actually observed. On the other hand, the interactive effect is linear to the extent that, in our case, the impact of Welfare State (ln) changes at a constant rate with the moderating variable on state capacity. We find some evidence for a non-linear effect of Welfare State (ln), though our main result is robust when explicitly modeling this possible non-linearity. Second, we consider three alternative estimation procedures: a Prais-Winsten regression with panel-corrected standard errors, a general error correction model, and a generalized methods-of-moments dynamic panel estimator. All three approaches control for temporal influences differently, and we can also shed light on short-term and long-term influences. Third, we disaggregate the democracy variable and employ dichotomous items for autocracy, anocracy, and democracy. Fourth, we replace the dependent variable by a more general item on greenhouse gas emissions. Fifth, as political ideology may have an influence on climate policy outcomes, we identify center-right executives and interact this binary variable with State Capacity * Welfare State (ln). We find that more interventionist, i.e., leftist executives, perform better and are associated with lower emissions. Sixth, we control for regional influences and consider a range of binary region variables as additional controls in our core model. Seventh, we explore the robustness of our findings when using an alternative indicator for the welfare state. Eighth, we control for the composition effect and include variables on agriculture and manufacturing as a share of the economy. Ninth, we employ an alternative indicator for state capacity using data in Hanson and Sigman (Reference Hanson and Sigman2021). Finally, we explore the subcomponents of the CPIA index, temporally lag all explanatory variables, and we list the countries and years covered by our analysis.

Conclusion

A common presumption in the environmental politics literature is that welfare-state institutions contribute not only to mitigating economic and social inequality and increasing political stability, but also to politically enabling ambitious climate policy by mitigating its negative economic effects on less affluent parts of society (see Kerret and Shvartzvald Reference Kerret and Shvartzvald2012). Thus far, the empirical evidence for this presumption has been inconclusive, however. In an effort to take this research a step forward, we argue that a synergistic relationship between the welfare state and climate policy and its outcomes in lower-income countries is more likely when state capacity is high. The underlying causal mechanism relates to mitigation of distributional implications and to perceived policy effectiveness and fairness (see Huber et al. Reference Huber, Wicki and Bernauer2020; Bergquist et al. Reference Bergquist, Nilsson, Harring and Jagers2022; see also Bechtel et al. Reference Bechtel, Scheve and van Lieshout2022; Povitkina Reference Povitkina2018). Specifically, (universalistic) welfare states seem particularly suited to compensate and protect those adversely affected by policy change and thus enhance perceptions of policy fairness. A high-quality state apparatus, in turn, is more likely to make citizens, also in lower-income countries, confident that adopted measures will be implemented effectively.

Our empirical analysis, which is based on data for 66 lower-income states between 2005 and 2018, offers robust support for this theoretical argument. The reason for focusing on climate change mitigation was that policy interventions in this area are particularly costly to large parts of society and have major distributional effects. Welfare state-based compensatory measures are thus likely to have a high potential for enabling ambitious policy change in this domain by softening the pain for losers. The reason for focusing on lower-income countries was both practical and analytical. While higher-income countries have already enacted a wide range of effective environmental policies, including climate change mitigation policies, lower-income countries are lagging behind. Moreover, while higher-income countries benefit from rather high levels of environmental quality, populations in lower-income countries still suffer from acute levels of environmental degradation. Hence, there is an urgent need to better understand the conditions under which lower-income countries can improve on their current predicament. Analytically, there is rather little variation in state capacity between high-income countries, whereas lower-income countries differ in this regard, as well as with respect to welfare-state characteristics. This makes testing the hypothesized interaction between welfare state and state capacity easier for lower-income countries.

Our research provides new insights into the drivers of variation in climate policy outcomes (e.g., Congleton Reference Congleton1992; Bernauer and Koubi Reference Bernauer and Koubi2009; Jahn Reference Jahn2016; Povitkina Reference Povitkina2018). Most importantly, we add to the theoretical and empirical clarification of the welfare state–climate policy outcome nexus, specifically with respect to lower-income countries (e.g., Kerret and Shvartzvald Reference Kerret and Shvartzvald2012; Bernauer and BoĴhmelt Reference Bernauer and Böhmelt2013; Lim and Duit Reference Lim and Duit2018; Zimmerman and Graziano Reference Zimmermann and Graziano2020), showing that the widely presumed synergistic welfare state–climate policy outcome relationship is largely limited to a particular type of welfare state with high state capacity.

Several interesting avenues for further research emerge from the work presented here. First, we argue that universalistic welfare states are exceptionally conducive to more ambitious and effective environmental policies. This argument is based on, among others, Rudra (Reference Rudra2007), Jacques and Noël (Reference Jacques and Noël2018), and Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1990) who all argue that less generous, less extensive, and, thus, less universalistic welfare states do not necessarily protect middle-class voters from negative employment effects, including those from more ambitious environmental policies. However, given the complexity of welfare states, it is quite difficult to measure the degree to which they are universalistic. Jacques and Noël’s work (2018) goes in the right direction here, but more research seems necessary.

Second, we have focused on explaining policy outcomes, on the presumption that, above and beyond other determinants, lower carbon emissions reflect more ambitious climate policy. We did so because reliable data on climate policy measures (policy outputs) is available for high-income countries, but is very heterogeneous and hard to aggregate in a meaningful way for lower-income countries (see also Nachtigall et al. Reference Nachtigall2024; Steinebach et al. Reference Steinebach2024).Footnote 6 Yet, it seems an effort worth making to distinguish between various climate policy types and their associated costs, especially since it is plausible that there are inherent differences across policy instruments. It is likely that this differentiation plays a significant role, also in light of the underlying argument related to compensation we set forth above. Future research could thus complement our work by examining welfare state and state capacity effects on environmental policy outputs (Nachtigall et al. Reference Nachtigall2024; Steinebach et al. Reference Steinebach2024) and, thereby, add to the literature on how economic, social, and political factors shape the environmental performance of societies more broadly (e.g., Gassebner et al. 2014; Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Böhmelt and Ward2017; Guy et al. Reference Guy, Shears and Meckling2023). Third, we have concentrated on CO2 emissions and, hence, climate change policy outcomes. It would certainly be interesting to find out whether our results uphold across different environmental policy domains.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X25000121

Data availability statement

Replication materials are available in the Journal of Public Policy Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/3BR5HH

We thank the journal’s editor, Charles Hankla, and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Acknowledgements

Funding statement

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.