Introduction

The intended goal of the budgeting function for democratic governments is to promote, facilitate, and improve the welfare of their citizens. It is becoming more common for countries to develop, release, and assess budget documents with the inclusion of non-financial indicators of success which are targeted towards gender equity, diversity inclusion, environmental sustainability, and human wellbeing (Durand Reference Durand2018). The use of wellbeing measurements alongside traditional economic measures of performance such as gross domestic product (GDP) helps to identify current societal problems and formulate appropriate solutions (Diener et al. Reference Diener, Lucas, Schimmack and Helliwell2010). Poland and Canada, for example, have introduced gender-based budgeting approaches. Italy also introduced an equitable and sustainable wellbeing framework in 2017 (Blazey et al. Reference Blazey, Lelong and Giannini2022). New Zealand was the first country to formally call its budget a wellbeing budget. The release of New Zealand’s first wellbeing based annual budget in May 2019 is considered an advance in policy formulation (Mintrom Reference Mintrom2019). To date, the country has implemented five wellbeing budgets (2019–2023). In 2024, the new coalition government chose to focus on fiscal responsibility (New Zealand Treasury 2024).

Several factors in New Zealand may have facilitated this policy change. One may have been the comprehensive new public management practices adopted in the 1980s because of the then weak economic conditions (Boston Reference Boston1990; Whitcombe 2008). A second may have been the decision in 1989, to increase government accountability for spending and the adoption of the Public Finance Act (New Zealand Legislation 2005). A third may have been New Zealand’s Anglo-Saxon colonial history and use of the British Parliamentary system, allowing ideas from other English-speaking countries to spread rapidly (New Zealand History 2022). A fourth may be the central government’s embrace of Indigenous Māori culture and language shown by the passing of the Māori Language Act (Benton Reference Benton2015). A fifth may be the country’s unique, isolated geography, protected ecosystems, strong central government, and small population of 5.1 million, all making it quick to make changes (Campbell-Hunt Reference Campbell-Hunt2008; Stats NZ 2022).

Another contributing factor could be New Zealand’s history of supporting women’s rights. It was the first country where women won the right to vote in 1893 (Archives NZ 2005), and it has elected three female heads of state, the first being Jenny Shipley in 1997 (Else Reference Else2018). Because of this context, New Zealand provides a unique case study of the factors that have facilitated the adoption of a wellbeing budgeting approach, and, from a broader perspective, a continuous evolution in public sector budgeting. Therefore, our research question is:

What are the key factors that contributed to the adoption of wellbeing budgeting in New Zealand?

From an outsider’s perspective, the adoption of a wellbeing budget may seem both radical and unexpected. Yet, New Zealand did manage to adopt a wellbeing budgeting. This study aims to identify the key factors that led to the major policy change in New Zealand and provide lessons for other jurisdictions which aspire to adopt a wellbeing budgeting or implement similar budgeting reforms.

This paper provides a further investigation into how New Zealand’s approach to budget reform has developed over the past three decades. We provide comprehension into how a policy of wellbeing budgeting was adopted. To determine the factors that may have facilitated this budgetary evolution, we focus on the decision-making stage of the five-stage policy cycle (Howlett et al. Reference Howlett, Ramesh and Perl2009).

Background context

A British colonial approach to budgeting in New Zealand began with settlers who set up a government in the mid 19th century (Moon Reference Moon2015). The founding document of the nation was the Treaty of Waitangi of 1840, signed between the British and Māori chiefs (Moon Reference Moon2015). Prior to British colonization, the land now known as New Zealand had been inhabited only by Māori peoples of South Pacific origin, who settled in the region in the 14th century (Holdaway et al. Reference Holdaway, Emmitt, Furey, Jorgensen, O’Regan, Phillipps, Prebble, Wallace and Ladefoged2019). When Europeans arrived from the United Kingdom (UK), they modeled their new government after a Westminster system of government. New Zealand has a centralized national government and one more tier of local government.

In the 1980s, New Public Management (NPM) reforms began to emerge and were adopted around the globe (Whitcombe 2008). They were furthered by ideology promoted by leaders including Ronald Reagan in the United States (USA) and Margaret Thatcher in the UK (Common Reference Common1998). In times of economic downtown, politicians are often determined to make government more efficient and effective. These NPM approaches also suited political agendas (Common Reference Common1998). NPM philosophies were adopted in New Zealand in the 1980s by the Labour government, although politicians lost votes, when the public correlated NPM with a decrease in public expenditures and significant cuts to services (Common Reference Common1998). Even with debate about the impact of NPM around the world, New Zealand is considered to have applied this ideology comprehensively (Duncan and Chapman Reference Duncan and Chapman2012), which reverberates in its public sector today.

Overall, according to Boston (Reference Boston1990, p. 6), New Zealand’s approach to NPM includes similarities to the approaches of other Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries:

A systematic programme of corporatization, privatization and commercialization; a greater reliance on competitive tendering and contracting out; the devolution of human resource management to the chief executives of individual departments and agencies; a move from cash-based to accrual accounting; improved systems of budgetary control; a greater reliance on financial incentives; and major changes in institutional design, including the placement of service-delivery functions in separate, non-departmental agencies.

Much of New Zealand’s government philosophy has been molded not only by its recent political and bureaucratic history, but also by having two orders of government, its small population, and self-sufficiency which is a result of an isolated geography. It is a nimble and small country, with a population of just over 5 million that is quick to adopt public sector reforms that may take years to be fully adopted elsewhere (Mulgan Reference Mulgan2008; Stats NZ 2022). A Westminster style of government, teamed with an active global expatriate community means that innovative public policy ideas flow readily from other countries. The Kiwis, as they fondly refer to themselves after their national bird, have a willingness to adopt public sector management reforms (Duncan and Chapman Reference Duncan and Chapman2012), make refinements over time, and support policy changes with evidence. Under these influences, New Zealand’s government has had a strong performance-based culture since the 1980s (Duncan and Chapman Reference Duncan and Chapman2012). Specific outcomes are defined, metrics are developed, and progress is regularly accounted for.

Developments in New Zealand’s public sector management include an early adoption of an accrual-based accounting system and the use of output-based data in the country’s budgeting system. In a public sector performance-based budgeting and accrual accounting study of New Zealand, Australia, and the UK, Marti (Reference Marti2013) determined that New Zealand was the first to fully adopt this approach in all departments in 1991. Australia followed suit in 1999/2000, and in 2001/2002 the British government adopted this approach (Marti Reference Marti2013). New Zealand used output-based information in its budget process for the 1991/92 fiscal year (Warren and Barnes Reference Warren and Barnes2003). Since then, over three decades worth of budgets and financial cycles, different governments have refined this process (Warren and Barnes Reference Warren and Barnes2003).

With a strong history of outcome-based or performance-based budgeting, New Zealand was primed for the adoption of further budget reform.

Theoretical framework

Policy adoption is a stage in the policy cycle. The policy cycle outlines agenda setting, formulation, adoption, implementation, and evaluation as the key points for any policy (Howlett et al. Reference Howlett, Ramesh and Perl2009). Adoption can be an uncertain stage that is decided by elected officials (priority setters) as the route or plan going forward. Several theories have emerged to explain this stage, including path dependence (Pierson Reference Pierson2000), advocacy coalition framework (Sabatier 1988), policy learning (Hall Reference Hall1993), policy diffusion (Shipan and Volden Reference Shipan and TVolden2008), punctuated equilibrium (Baumgartner and Jones Reference Baumgartner and Jones1991), institutional change (Streeck and Thelen Reference Streeck, Thelen, Streeck and Thelen2005), multi-level governance (Hooghes and Marks Reference Hooghes and Marks2003), policy networks (Rhodes and Marsh Reference Rhodes and Marsh1992), and disruptive innovation (Christensen et al. Reference Christensen, Horn and Johnson2008). Another often-used theory in policy adoption is John Kingdon’s (Reference Kingdon1995) three-stream policy adoption framework which includes – a problem, a proposal, and the politics. Our paper tests David Good’s theory (2014) about how political budget actors will make decisions at the policy adoption during the decision-making of the policy cycle.

The guardian-spender framework of budgeting

Budgeting has both technical and political dimensions. The technical aspect of budgeting addresses how the budgeting process is characterized – incremental, performance-based, or productivity-based with an efficiency dividend (Tellier Reference Tellier2019). The political aspect of budgeting looks at the interaction between budget actors, including the tensions that underlie their roles. Good (Reference Good2007) studied the political aspect of budgeting by identifying key budget actors and their motivations in the budget process. In Wildavsky’s (Reference Wildavsky1974) guardian-spender framework, guardians conduct decisions made by politicians, while spenders are bureaucrats from line agencies or ministries tasked with providing services. Guardians usually include the Treasury Board Secretariat and the Department of Finance. Their major responsibilities are tax collection, budget allocation, program management, monitoring, and reporting.

David Good (Reference Good2014) developed a theory that included additional budget actors – priority setters and watch dogs. Priority setters (politicians or decision-makers) are elected by the voting public to decide policy outcomes and set priorities for budgets during their term (Good Reference Good2007). Financial watch dogs audit the budget process and provide oversight for budget inefficiency and program expenditures (Good Reference Good2007). Budget reform should not strengthen the power of any specific actor in the budget process but improve the interaction between these groups of actors (Good Reference Good2014). When the political aspect of budgeting is recognized and accounted for, technical budget reform is best achieved. In terms of the political aspect, Good (Reference Good2011) argued that better information channels among all actors in the budget process leads to better allocation and expenditure decisions, allowing every budget actor to exert their control over high-quality information rather than over copious quantities of data.

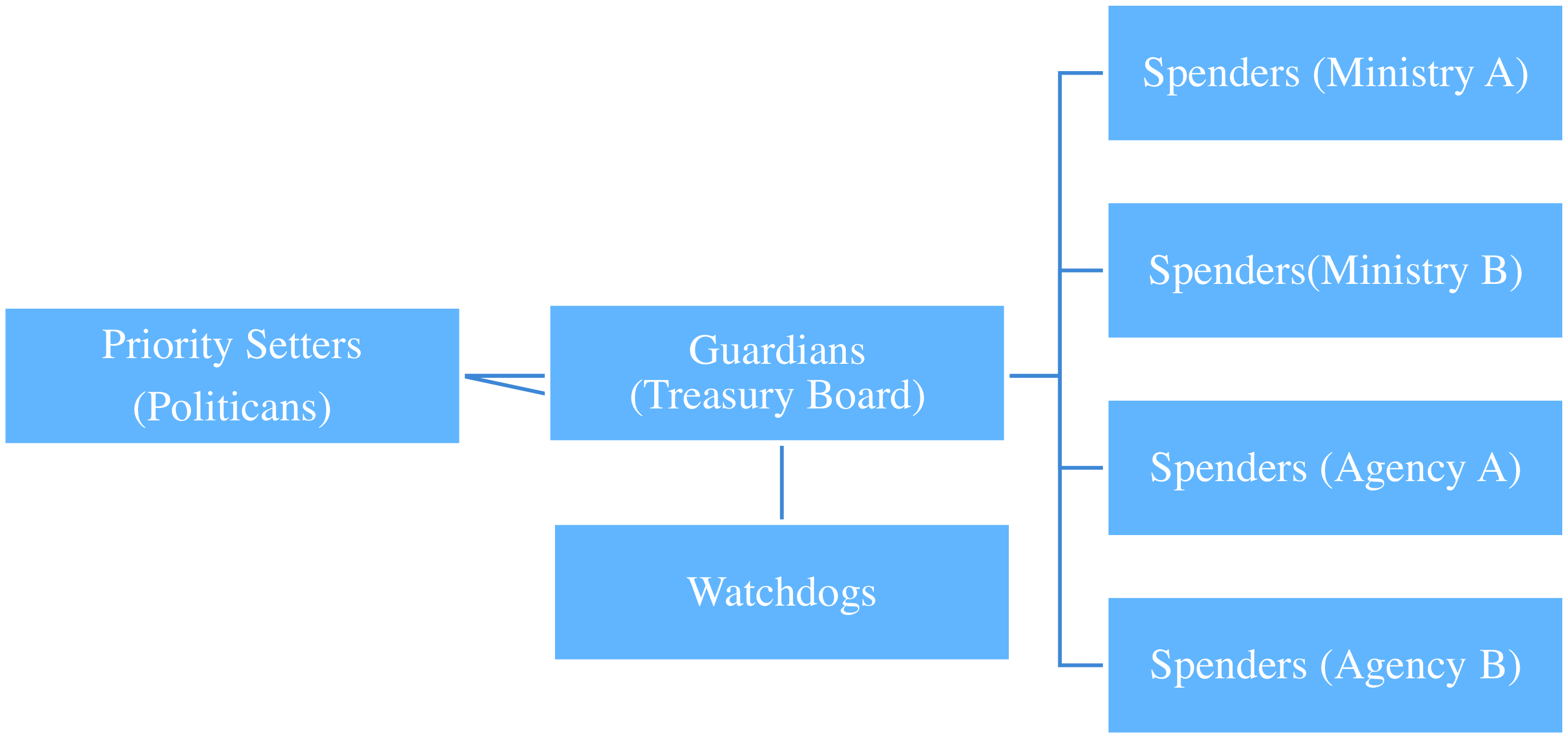

According to Good (Reference Good2014), the success of any budget is influenced by the relationships, flow of information, and interactions between these actors. These budget actors play diverse roles in the budget process, and they can be motivated (or legislated) to use performance indicators such as productivity or wellbeing targets to their own advantage. The relationships between each budget actor in the budgeting process are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Budget actors in budgeting according to David A. Good (Reference Good2014). Source: Good, D.A. (2014). Politics of public money: Spenders, guardians, priority setters, and financial watchdogs inside the Canadian Government. (2nd ed.), University of Toronto Press.

Given the structure of budgets in many Western countries, there is an inherent tension between spenders and guardians as the first seeks to maximize their individual budgets whereas guardians (Treasury Board) manage the needs of the whole government. Spenders are incentivized to spend all money allocated to them on an annual basis (Niskanen Reference Niskanen1991), and the public often asks for more to be provided through priority setters (elected decision-makers). It is advantageous for spenders to spend their money rather than have unspent money at the end of the fiscal year, which would signal to guardians that spenders require less funds the following budget cycle.

Guardians and priority setters have an important relationship (Good Reference Good2007). Guardians are responsible for overseeing and ensuring the implementation of decisions made by politicians. Priority setters seek to be re-elected and, therefore, consult their electorate, as well as guardians and spenders, when making policy decisions (Good Reference Good2007). Priority setters will also be influenced by outside interest groups. Priority setters make allocation decisions, decide on acceptable amounts to spend, and provide justification for increased expenditure or cost reductions. The relationship between these two budget actors is often the catalyst for larger shifts in government budgets (such as adopting wellbeing as a budget’s outcomes) beyond routine, incremental budgeting decisions. Although, often because of the differing desires of guardians and spenders, the budget process is often incremental.

A budget reform involves acknowledgement of both technical and political dimensions.

Technical budget reform, such as tying outcomes to expenditures, is best achieved when the political aspect of budgeting is functioning well. A desirable budget reform should not strengthen the power of any specific actor in the budget process but rather improve the interaction between actors (Good Reference Good2014). Yet, it is predicted that the shift of power dominated by either spenders or guardians can be influenced by larger political, economic, social, and technological factors. Strengthened interactions between guardians and spenders can improve the flow of information about program costs and demands from the voting public. Improved information flow between priority setters and guardians can help to better match overall policy objectives with available funds.

Wellbeing and public policy

Questions about the effectiveness of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as a sound measure of national wellbeing has sparked a multi-decade, ongoing discussion, study, and debate about what should be measured, how it should be measured, and what determines how well people are doing (Hoekstra Reference Hoekstra2019). As government actors, academics, international institutions like the OECD have argued, GDP, in conjunction with other economic indicators, are insufficient for determining how well a country and its citizens are doing (OECD 2018; Diener et al. Reference Diener, Lucas, Schimmack and Helliwell2010; Graham Reference Graham2011; White Reference White2008). Other measures of a country’s progress include the extent of poverty and inequality, environmental quality, health, and mental health status, etc. For example, accounting for a country’s progress using only economic indicators means that the health of the planet is not considered. In the name of economic growth, people have influenced the composition of the atmosphere with increasing levels of emissions and unsustainable land use practices (Karl and Trenberth Reference Karl and Trenberth2003). Recognizing that GDP was an inadequate measure for goals such as planetary health (Hoekstra Reference Hoekstra2019), New Zealand, known for its progressive policies, set about finding another way to measure the country’s progress towards better citizen wellbeing.

Along with several other countries, New Zealand began a process in the early 2000s to identify natural, human, and knowledge resources that contribute to the real wealth of a nation beyond what is spent annually on programs and policies. The National Party, in power at the time, aimed to provide better social services to New Zealanders while being more fiscally responsible than other parties. For example, child poverty is common policy problem in New Zealand. The goal of the government was to use current investments (or public expenditures) to enable individuals to contribute to the economy rather than rely on it in the future, thereby reducing people’s dependency on the state. The process involved calculating the total cost of one person who is dependent on the system over their life cycle. It was reasoned that a young child receiving social services would be more likely to have encounters with the justice system later in life, resulting in a lifetime of costs to the public system.

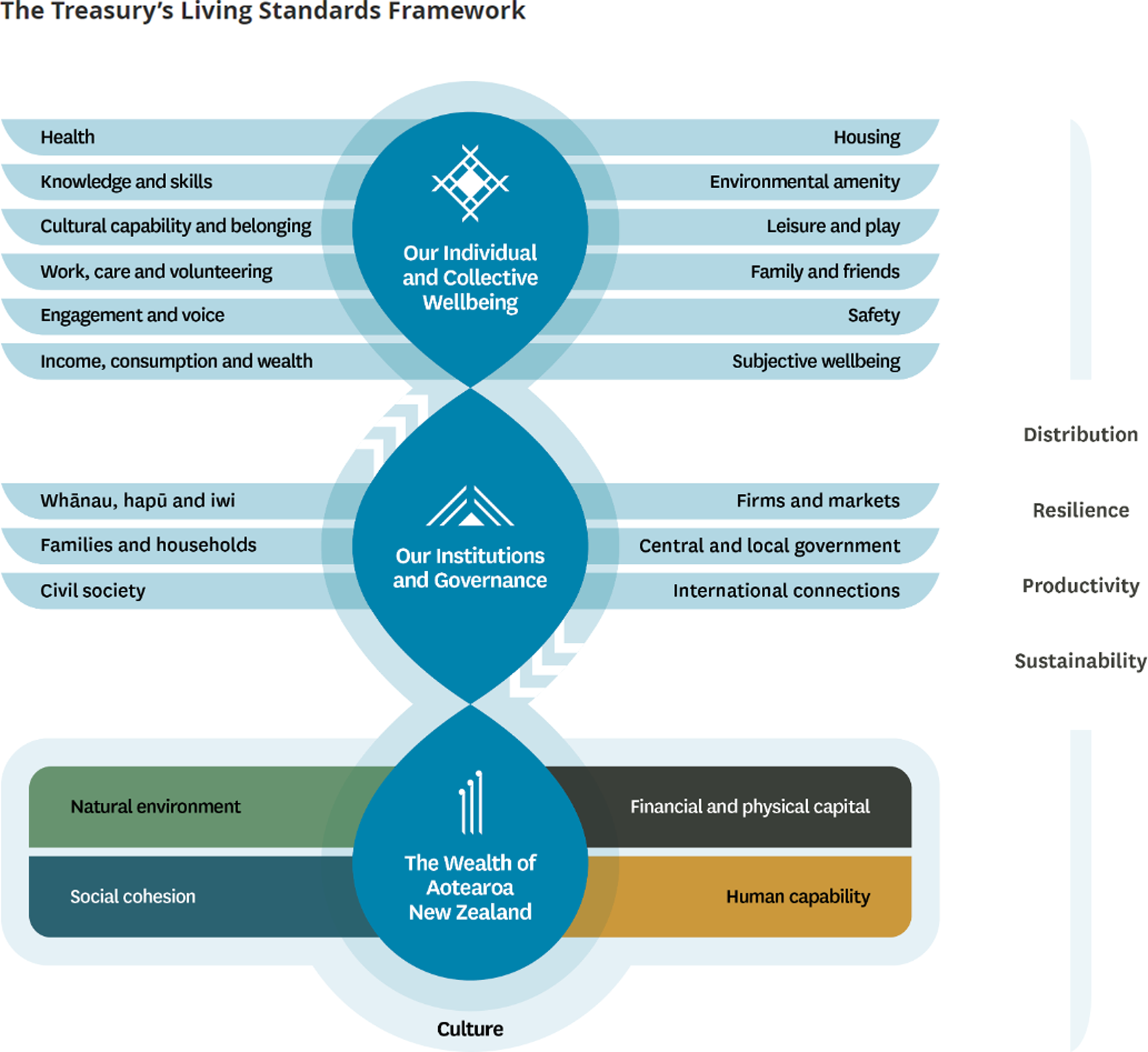

In New Zealand, under the National Party government a challenge group consisting of Treasury officials and academics was assembled and tasked with creating a framework that would assess wellbeing outcomes in new budget bids. This process resulted in the development of the Living Standards Framework (LSF) (Figure 2; New Zealand Treasury 2021) to operationalize the social investment approach. With this framework, New Zealand’s Treasury aimed to capture and account for wellbeing indicators beyond economic factors.

Figure 2. New Zealand’s treasury living standards framework. Source: New Zealand Treasury (2022, April 12). The Living Standards Framework (LSF) 2021. New Zealand Government. https://www.treasury.govt.nz/publications/tp/living-standards-framework- 2021.

New budget bids were meant to be filtered through a social investment lens and re-orient public sector spending towards an “equity-informed welfare provision” (O’Brien Reference O’Brien2020, p. 111). The LSF committed all ministries and agencies to focus on the outcome of wellbeing in four dimensions: the natural environment, financial and physical capital, human capability, and social cohesion (New Zealand Treasury 2021). LSF’s implementation meant that politicians and bureaucrats were encouraged to work together to find cross-ministerial objectives to meet the potential of New Zealand’s citizens. The wellbeing budgeting approach evolved further once Jacinda Ardern’s Labour Party was elected in 2017 and decided that it would continue to use the LSF to measure wellbeing. This government was applauded the world over for being the first to introduce wellbeing into its budgeting process (Dalziel Reference Dalziel2019).

The adoption of the wellbeing budgeting

Very few studies have looked at New Zealand’s approach to wellbeing budgeting. A description of the Kiwi and Australian approaches is provided by Moll et al. (Reference Moll, Ang, Kuruppu and Adhikari2024) who provided an analysis of publicly available documents, reports, and media sources. This study identifies wellbeing budgeting as a tool for governance (Moll et al. Reference Moll, Ang, Kuruppu and Adhikari2024). Yet a challenge present is access to reliable data to inform decision-making (Moll et al. Reference Moll, Ang, Kuruppu and Adhikari2024). This point is emphasized in Upton’s (Reference Upton2022) work which highlights that environmental issues are now being linked to wellbeing budgets – one of the main aims of adopting them in the first place.

A precursor to wellbeing budgeting in New Zealand was performance-based budgeting. Another budget reform adopted and recently studied is participatory budgeting. A case study conducted by Clark et al. (Reference Clark, Menifield and Stewart2018) highlights a larger “program of governmental reform that executive agencies were more important than parliaments in managing it” in 33 OECD countries which implemented this budget reform (p. 528). Additionally, Krenjova and Raudla (Reference Krenjova and Raudla2018) identified policy diffusion as being led by learning and imitation. Hence, the evidence suggests that significant changes to a budgetary process happen when one considers internal politics and the larger policy environment.

In this study with budget actors involved in the formulation and adoption of New Zealand’s wellbeing budgeting approach we have applied the guardian and spender theoretical framework to comprehend the politics present in the adoption of New Zealand’s wellbeing budgeting. Our objective was to assess Good’s theory of the politics of public money which has not been applied to analyze many instances of real budget reform. Significant budget form is rare and therefore, we sought to identify the pre-conditions and factors which have led to innovative wellbeing budgeting.

The guardian and spender framework describes the tension and interaction between budget actors. Good (Reference Good2014) hypothesized that the politics between priority setters and guardians, as well as between guardians and spenders, impact the result of any budget reform. Priority setters are significantly influenced by the demands of the public and the problems they perceive need to be solved, whereas guardians (or budget officers) are concerned with the internal workings of government.

Priority setters may identify a policy problem to be addressed, in the case of this paper – a budgeting process that accounts for wellbeing and a financial method that incorporates the Living Standards Framework (LSF) into national budget allocations. Guardians and spenders participate in policy adoption as they identify improvements that can be made to current budget processes. With budget process reform, the interactions between all these actors influence what approach is adopted to address policy problems.

Another key budget actor that was added to the framework by Good (Reference Good2014) were watch dogs. This non-political budget actors’ role is to add another layer of scrutiny to New Zealand government, which includes: the ombudsman, controller and Auditor-General, and the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment (New Zealand Parliament 2019). We have chosen to not include watch dogs in this study as we focused on implementer budget actors who engaged in prioritizing wellbeing and adopting it as part of the budget process, rather than those who oversaw it. We do hypothesize that their role in the adoption of New Zealand’s wellbeing budgets would continue with their regular responsibility of overseeing New Zealand’s government (as per their publicly available website): conducing inquiries; annual auditing function of financial statements; performance auditing; and controller function of government spending (New Zealand Controller and Auditor-General 2024).

We posited, in accordance with Good’s (Reference Good2007, Reference Good2014) theory, that the politics between budget actors had an impact on the creation and adoption of the LSF framework and, consequently, the country’s subsequent wellbeing budgets. As well as tensions between budget actors, we posited that there were internal and external political, economic, social, technological, environmental, legal, and international influences at play exerting pressure on this process. The public (through consultations) may have also influenced the process, exerting pressure on priority setters on the final budgeting outcome. The methodology to study and evaluates these hypotheses is discussed in the following section.

Methodology

The research strategy for this study was a case study method, which allowed for purposeful sampling (Patton Reference Patton2015). New Zealand’s adoption of wellbeing budgets since 2019 was chosen as a case as it is a recent and innovative budgetary policy development. Our aim was to identify key factors that influenced the adoption of the wellbeing budgets in New Zealand. The “black box” of budgeting decisions is often unknown to the public. Therefore, to open the metaphorical lid of said “black box,” we believe interviews with key priority setters, guardians, and spenders who had been involved with the development either of the LSF or with New Zealand wellbeing budgets are the best way to identify the themes that influenced policy adoption. The purpose of these interviews was to gain insight into the interactions between key budget actors, to identify factors present during policy adoption, and to determine which of these factors the actors considered to be key to the adoption of the policy.

This methodology was selected and employed as it is helping to study a network of key actors and their perspectives on the budgetary process. Case studies encourage both deduction and induction of new information, concepts, and ideas (George and Bennett Reference George and Bennett2005). The disadvantages to the case study method include case selection and the high potential for selection bias; the difficulty of generalizing findings to a larger sample size; the inability to control for case comparisons; and the difficulty of determining the frequency of cases (Bennett and Elman Reference Bennett and Elman2006). These concerns were addressed by reaching out to a large sample size of interview participants To mitigate our own selection bias, we employed snowball sampling (Parker et al. Reference Parker, Scott and Geddes2020) which began as convenience sampling but also meant that participants, who were close to the budget process, recommend participants they thought would provide important input into our study.

In any case study, one must realize that findings are not meant to be generalized as they would be with a larger sample size. The benefit of a case study method is to study a new and innovative phenomenon that does not yet have a significant number of observations to conduct a full empirical study. Therefore, it is important that this research is viewed as an individual piece with the larger public sector budgeting literature, which includes a strong tradition of quantitative work.

Research method – key informant interviews

Our main research method for the New Zealand case study of wellbeing budget adoption was key informant semi-structured interviews. We chose this interview method as it allowed us to do an in-depth inquiry into interviewees’ personal perspectives and experiences (Patton Reference Patton2015), which then enabled new information and themes to emerge from participants themselves. Interviewees often spoke at length without interruption as they often inadvertently anticipated the questions we wanted to ask.

Interview questions were developed with reference to Good’s (Reference Good2014) budget actor framework. All participants were asked a series of open-ended questions about their current role and the position they held when the first wellbeing budget was adopted in 2019: How the idea of a wellbeing budget was brought onto the agenda? What influenced the adoption internally and externally? Did any key actors champion the wellbeing budget? What was the role of the public? Were alternatives considered, and, if so, which ones? We asked participants about other policies that could be used to achieve the desired outcome of wellbeing.

Guardians were asked two sets of questions that applied to both the adoption and implementation of the wellbeing budgets. Interview questions were also amended depending on who the participant was. Many sent us reports and articles that they had published to read in advance of our interviews. We adapted questions to ensure that what they had provided was being considered and expanded with our questions to suit their experience and field of study, especially those now working in an academic setting. The interviews were conducted using Zoom and lasted 45 minutes to two hours.

We first contacted every minister in the Labour Party government in January 2021. This process provided us with only one person to interview, who did not belong to the political party in power at the time. We then sent interview requests to the authors of wellbeing related reports authored by New Zealand’s Treasury. This proved to be a fruitful sampling method, as we received many favorable responses from current or former Treasury officials who agreed to be interviewed for our study, especially from those who had been part of the challenge group assembled by Finance Minister Bill English to develop the LSF.

Recommendations were made by interviewees in all categories – priority setters, guardians, and spenders on who to contact next. We were then able to contact former and current politicians, bureaucrats, and even academics who had worked in New Zealand’s Treasury challenge group to establish the LSF (Karacaoglu Reference Karacaoglu2015). Speaking to former Treasury officials (guardians) from New Zealand highlighted the importance of interviewing spenders from ministries that had embraced the wellbeing approach in their respective departments and ministries. Therefore, our sample of spenders constituted a group of budget actors who were more receptive to adopting the wellbeing approach than those from other ministries might have been. This is an aspect of our study that could be addressed with further work.

A drawback to our approach was that it was difficult to recruit current priority setters for this study, as New Zealand has a three-year election cycle, so those in government are tasked with achieving their political objectives in a short time. Interview requests were also impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. When we emailed each minister in government, we received responses from their administrative personnel indicating that they did not have the time to be interviewed. Only one current politician and one former politician participated in the study. Most participants (nine of 22) had an academic affiliation, either as former guardians in the Treasury challenge group or as academics in budgeting or public policy. We were surprised by the large number of academics who had previously worked in Treasury, as it was our assumption from a Canadian perspective that academics do not often occupy guardian roles or vice versa.

We asked interviewees questions to illustrate the extent to which politics, i.e., bargaining between budget actors, is at play in the New Zealand budget processes: whether and how much the budget process is influenced by internal actors and directives (this question was also asked to identify policy entrepreneur(s) who may have championed the wellbeing budget process). We also asked them to discuss the external context influencing the budget process. Not intended to lead respondents, this question was asked because we anticipated that many would mention the influence of the OECD on the adoption of the wellbeing budgets.

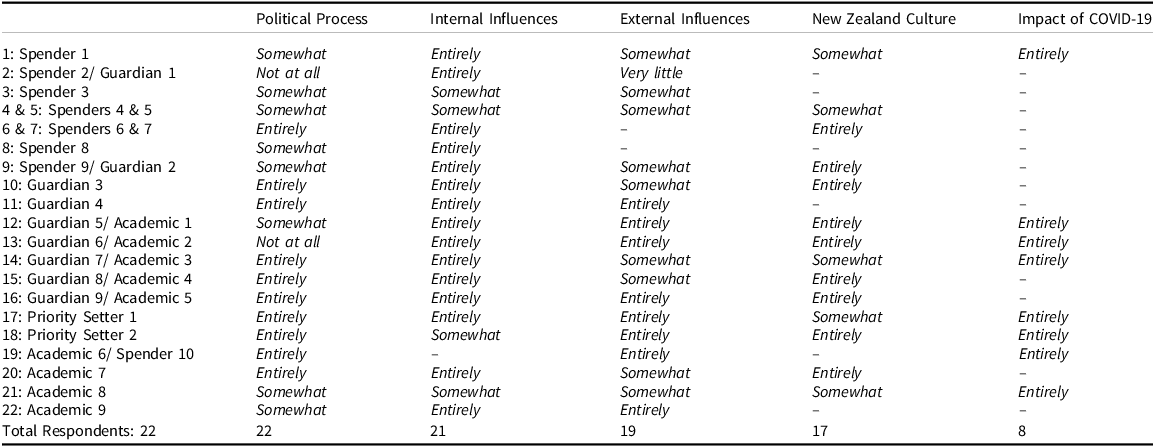

Analysis of interview data

All interviews were recorded and later transcribed using Otter.ai software. We reviewed the recordings and transcripts for accuracy and made changes if the transcripts were unclear. Data were first analyzed deductively. Deductive coding of the interview data helped to show the extent to which adoption of wellbeing budgeting in New Zealand was politically influenced, according to Good’s (Reference Good2007) framework which postulates how budget actors will behave according to their roles and motivation. We then categorized responses to this question on a four-point Likert scale (not at all; very little; somewhat; and entirely) based on how much the adoption of the wellbeing budgets in New Zealand were politically influenced; the extent to which this budget reform was influenced by internal actors who were privy to the process and tensions between them; the extent to which external influences were present; how much New Zealand culture influenced the adoption; and the impact of COVID-19. A Likert scale was employed (Willits et al. Reference Willits, Theodori and Luloff2016). The analysis of these factors is found in Table 1 of the Results section.

Table 1. Interview Coding Results

After the first round of deductive coding, we inductively looked for pertinent themes in the interview transcripts with a grounded theory approach (Joffe Reference Joffe, Harper and Thompson2011; Strauss and Corbin Reference Strauss and Corbin1990). This iterative process involved a careful reading of each transcript to analyze a significant of amount of raw data; to connect our research objective with our results; and to add to the current theory of politics of budget actors from a novel case study (Thomas Reference Thomas2006). To simplify a broad narrative of the results, we searched for “patterns and themes” (Patton Reference Patton2015). Factors were tallied based on how often the interviewees discussed them and grouped into themes that emerged in most interviews. We identified approximately 30 themes per interview after the first reading. Then, we distilled them to the major themes described below. Quotes from the interviews that support the specific factors we identified are emphasized.

Interview results

A total of 22 participants were interviewed in 20 interviews – 10 spenders, nine guardians (current or former Treasury officials), two priority setters (politicians), and nine academics. Two sets of participants chose to be interviewed together, and eight interviewees had worked in more than one role in government. Eleven participants were not working in government at the time of study. There were two participants who had been guardians (Treasury officials) and were now spenders (in a ministry). They spoke about their work on the development of the LSF, wellbeing budgeting, and how this approach affected their work at the ministerial level. No participants occupied two roles at the same time. When addressing our questions, participants answered from the perspective of their current and former roles in government.

Many participants had worked in government during the development of the LSF and prior to the release of the current wellbeing budgets. According to interview participants, there was an active exchange of ideas between New Zealand’s Treasury and academic institutions in the country and abroad both during the development of the LSF and in present times. Participants answered our questions based on which experience was relevant to the question we were posing. For example, when we asked about internal influences on this budgeting approach, they would answer how a priority setter may have impacted them as a guardian or how their role and focus had changed now that they were a spender with a larger role in implementing the budget as opposed to reviewing budget bids as a guardian. Because two sets of two spenders were interviewed together, their responses were coded together. Spenders were from the Ministries of the Environment, Transport, and Ministry of Business, and Innovation and Employment (MBIE). See Table 1 for the categorization of interviewees’ roles using Good’s (Reference Good2007) framework.

We asked questions in three areas related to the political process of adopting the wellbeing budget: whether internal influences were present; how much influence external factors had on the budgeting process; and how much impact New Zealand’s culture had on policy development. Although we did not ask a specific question about COVID-19, it, of course, came up in the interviews as they were conducted in the summer of 2021, during lockdowns. We therefore have an additional theme on whether this budget policy was impacted by COVID-19. Factors were assessed on a Likert scale of “not at all” to “entirely.” Table 1 is a summary of the deductive coding for questions.

Political process

For participants, the word “political” meant the actions of the governing party of priority setters who set the political agenda. When asked if the adoption of the wellbeing budget was a political process, suggesting it was led by priority setters, 90% of interview participants indicated the adoption was “entirely” (12) or “somewhat” (6) political. One guardian said, “the politics reflects, you know that in [a] functioning democracy, the politics to some extent reflects what people view as beneficial to themselves” (Guardian 4).

The participants made notable statements about why the wellbeing budgets were adopted at this time, with several linking New Zealand’s government culture with the need to achieve specific outcomes for investments. Several pointed out that the foundations of the wellbeing budgets had been laid 40 years earlier. One former Treasury official (Spender 2/ Guardian 1) indicated that the wellbeing budgets were strongly influenced by the passing of the Public Finance Act (1970) and financial restructuring in the 1980s intended to bolster the faltering economy. As this interviewee said, this Act (1970) “had a strong emphasis on linking funds to outcomes … so, in a sense, the wellbeing work [of the 2000s] was another iteration of that attempt by ministers to make the system work as it was originally intended in the 1980s.” They continued to speak about the “dramatic restructuring” that occurred at that time. In the 1989 amendments to the Public Finance Act were made to officially require budgets to have performance indicators.

In the early 2000s, the national government began to prioritize longer-term costs, moving away from relying on annual budget rounds, “with all the maneuvering and gaming that goes on, to take a longer-term view about the quality of government agencies management” (Priority setter 2). Another interviewee echoed this statement: “We already asked for a lot of work [and budget reform] over several years, which is the key thing” (Guardian 3).

Before the LSF was released in 2011 by the Treasury, the National Party government had begun work on a social investment approach. One participant commented that the LSF was developed because fostering people’s dependence on government services – from foster care to the prison system – made no financial sense. Social investment policies were intended to assist people in becoming self-sufficient rather than relying on public services.

There was political support from different New Zealand political parties, which facilitated the creation of the LSF, its operationalization, and the foundation of the wellbeing budget approach. One participant (a former guardian) spoke of the support this way: “In New Zealand, it has been ministers of finance from both the left and the right, who have been interested in the wellbeing agenda, and here the wellbeing framework came out of Treasury.” However, according to one former guardian 9 /academic 5, the (previous) right-of-center National Party was not supportive of the wellbeing work carried out by the Labour government of Jacinda Arden, indicating that the National Party “had no intention of taking it seriously from a public policy perspective” because the budget was associated with the Labour and Green Party government. Despite this view, the consensus among the majority participants was that the National Party was supportive of the wellbeing budgets.

In this research, we categorize both Sir Bill English and the Treasury challenge group as policy entrepreneurs (Mintrom Reference Mintrom2020): Bill English from his days in Treasury as a bureaucrat, to Finance Minister with the National Party government, and ultimately to Prime Minister for championing the approach that has become known as the wellbeing budgets. Another guardian/academic, who worked with the Social Investment Agency, said that what English did well was “capture the wellbeing impact of social housing and how much it costs,” adding, “one of the brilliant things that English did was he got Statistics New Zealand to actually create a research data set that looked at the individual level.” Coming from a more fiscally conservative background than the current party in power, this guardian knew that evidence-based social service investments have the potential to move people out of poverty to a place where they could contribute to the economy rather than relying on public services.

Many attempts at implementing a wellbeing approach have, interestingly, come from the political right. Guardian 4 highlighted that former French president Nicolas Sarkozy, a center right politician, commissioned a study to measure wellbeing (Easterlin Reference Easterlin2010). Similarly, David Cameron, a Tories center right politician, while serving as British Prime Minister, declared wellbeing would replace GDP as an indicator of a country’s progress (Copley Reference Copley2011). Even Benjamin Netanyahu, who is past center right, began this conversation in Israel. Guardian 4 continues:

If you looked at it up until that point, almost all the attempts to incorporate wellbeing to policy had come from the right of politics, and this was driven, I think, very largely by a sort of post-Tony Blair, Bill Clinton, kind of middle of the road environment, where the left had been trying to be moving to the centre and basically pitching themselves as we are more competent economic managers that the right end, but more humane. So, when the right came in, the wellbeing stuff was politically very useful. It shows that we have a soft side and subtle stuff that comes out of that.

The participant added,

The current Labour government is just about the first left-wing government that is really nailed the wellbeing sort of colours to the mast. Treasury had the wellbeing framework that predated that.

It is our understanding that what participants understood to be political included the governing party at the time and the priority setters who set the political agenda. The wellbeing budgeting approach took shape once the Labour Party was elected and decided that it would use the LSF as the measurement tool for a wellbeing budget.

Internal influence, directives and tensions

Most respondents (90%) indicated that internal government budget actors influenced the wellbeing budget adoption and implementation “entirely” (14) or “somewhat” (4). We asked this question about internal influence to identify whether priority setters had set the wellbeing agenda for guardians and whether guardians were motivated to adopt this approach to have their budget bids approved. We wanted to test Good’s theory of tensions between major groups of budget actors. The responses we received were due to the influence of guardians and members of the Treasury as they were the most important and largest group of participants we connected with. One guardian/spender described an evolution in thinking in Treasury over the past 20 years:

I think, previously, the Treasury’s view had been that if people [the public] had opportunities, then that was what the state needed to deliver. By providing public health, public schooling, people had opportunities. If they did not use their own self-motivation to make the best of those opportunities, then that was on them.

Internal actors included guardians (Treasury officials), as well as the challenge group that developed the LSF. Here, we were looking to see if there were tensions between priority setters and guardians in adopting this budget. For these individuals, a key factor in the adoption of the wellbeing budgets was the development of the social investment approach. When the New Zealand decision-makers considered a citizen’s life cycle, they determined that a social investment approach was less costly than a standard approach and encouraged investment in areas like those the LSF had laid out: individual and collective wellbeing; institutions and governance; and the wealth of Aotearoa and New Zealand, including the natural environment, social cohesion, financial and physical capital, and human capital (New Zealand Treasury 2022).

As mentioned, the social investment approach was deeply entrenched in the LSF, which had been developed by Treasury officials and a challenge group of academics, who were tasked with using the social investment approach when they presented new budget bids to the ministries. Key to the social investment approach was that it took an evidence-based approach to public policy. In other words, evidence (and performance metrics) was required to demonstrate that funding was making an impact on people’s lives. As priority setter 2 said, “New Zealand’s got the best integrated public service data in the world, which is an incredibly powerful social science resource. Because you can run virtual experiments on anything you like, using real data about real people.”

Because of its tight connection to academic institutions, The New Zealand Treasury had the research capacity to produce the evidence it needs to support policy. As a member of the Treasury challenge group put it, “Treasury is the best university in New Zealand that isn’t a university.” Another interviewee, who had worked in New Zealand’s Treasury mirrored this sentiment by indicating that internal government culture is aimed towards advancing economic thought and the implementation of evidence-based policies beyond its current level.

There was general acceptance of the social investment approach and agreement to rely on research evidence, and most participants claimed that budget actors cooperated with each other, conversing, and debating to arrive at the best outcome. Despite the general spirit of cooperation, some participants indicated that tensions existed both between priority setters and guardians and unexpectedly within groups of budget actors themselves (i.e., tensions between one priority setter and another priority setter from differing political priorities or between one guardian and another guardian). According to some participants, guardians disagreed on how to implement wellbeing budgeting, how to measure its success, and how to show evidence that investments were, in fact, leading to the desired outcome. As Spender 6/Guardian 2 indicated “…there was about eight years’ worth of internal intellectual debate about the [LSF] framework and how it should be applied to the work of the Treasury and the budget process.” We see the tensions within guardians.

We see the tensions within guardians as an example of the heterogeneity among members of a budget actor group. Thus, the theoretical framework (Good Reference Good2007) that postulates that each group of budget actors has similar motivations, and predictive behaviors may need to be updated.

Guardian 4 made this point when they said that Treasury was not “a monolithic actor” in the development of the wellbeing budgets. Guardian 9/Academic 4 said “people [in Treasury] started with a worldview [without acknowledging it] and went straight down to the indicators.” The conceptual footing that they were starting on needed to be identified before indicators were selected. At the beginning of this work, there was a “very large institutional sense that this [wellbeing budgeting] had not gone anywhere…and a lot of people had been alienated.” For example, Spender 10/Academic 6 emphasized that the wellbeing approach needs to be focused on climate change:

…if we are going to make serious progress on climate change and address powerful vested interests, the public must have a much deeper knowledge of what’s at stake and what is needed to redress the problem.

The tension within groups of priority setters, guardians, and spenders has as much of an impact, if not more, on final budgeting outcome as do tensions between the groups.

Larger external political environment

A large majority of respondents (94%) said that the adoption was “entirely” (8) or “somewhat” (10) influenced by external influences. New Zealand was influenced by the larger external political environment which included global trends in the measurement of wellbeing, beginning with the Sarkozy Commission in 2008 in France; public policy developments from Australia; and an exchange of ideas with the OECD (Kroll Reference Kroll2011). As New Zealand was developing its LSF, it was influenced by the OECD Better Life Index (OECD 2018).

The response below suggests that pre-conditions external to the Treasury or to spending departments were critical to the adoption of the innovative wellbeing budget in 2019. Several participants indicated that the global trend of measuring wellbeing at a national level influenced New Zealand’s eventual adoption of the wellbeing budget. A former Treasury official described how the wellbeing budgets came to be after the Sarkozy Commission in France:

The Chief Executive of the New Zealand Treasury asked a group of analysts to investigate this and see what could be learned from it (the report of the Sarkozy Commission) and whether anything can be applied for New Zealand public policy. And concurrently, or before then in Australia, the government was already starting to think about this broader framework.

Another element of the external political context that were noted included exchanging public policy ideas with the OECD and staying abreast of budget developments in Australia. Overall, this influence seemed to have moved in both directions – the OECD’s wellbeing directives influenced New Zealand’s implementation plans, and New Zealand had an impact on OECD’s promoted approach. One guardian/spender indicated the following:

I think that when it comes to thinking about how you think about a wellbeing budget, there are a lot of choices. And so, the person who drove the work at the time, who was the deputy chief economist, had a strong measurement focus, and it was derived from the OECD work on Better Life Index.

No participants indicated that the public had considerable influence on the adoption of these budgets. The extent to which budget actors are influenced by the public is based on their role. Priority setters, like politicians, are the budget actors closest to the public. Guardians are the furthest away from the public, relative to spenders, who administer and implement programs and services for the public.

Pre-condition of New Zealand culture

Seventy percent of respondents said that New Zealand culture had “entirely” (9) or “somewhat” (5) influenced the development of the wellbeing budgets. New Zealand culture embraces the Kiwi approach of “giving it a go,” in other words, an enthusiasm for trying new things. Kiwis have a keen sense of agency. Guardian 10/Academic 5 indicated that “Kiwis come from a place, generally speaking, of friendliness, rationality, practicality and pragmatism.” Culture in this context can mean a strong public K-12 education system that produces graduates with analytical skills. Being a remote and small country also means that there is a sense of fending for oneself. Another key element of Kiwi culture is an embrace of Māori language, customs, and traditions which leads to a strength in diversity.

Impact of COVID-19

Although we did not specifically ask participants about COVID-19, eight interviewees mentioned its impact on the most recent budget. Operationalizing the LSF and the wellbeing budgets during the pandemic was halted, according to one guardian/academic:

Then the COVID-19 crisis hit us all. And we got distracted. As it stands today, in New Zealand, there are many, many measures of the various components or domains of wellbeing, there are many measures of the capital stocks associated with wellbeing. But in terms of having a coherent framework, through which we assess and prioritize a series of public policies, we are behind on that one. A serious modeling effort was made some years ago, but it was put to one side.

The consensus amongst participants who brought up the COVID-19 pandemic was that a refocus on wellbeing was required. And even though the wellbeing approach to budget has been adopted and supported by all levels of government, it still requires empirical backing to better facilitate it. By this, it meant that a better understanding on the correlation between specific programs and policies and their outcomes. A database of evidence-based policies that show significant changes in wellbeing outcomes needs to be done.

Discussion – theoretical implications

Budget reform which builds upon a performance-based budgeting system and is tied to wellbeing indicators globally is a rare occurrence. Yet New Zealand adopted a wellbeing budget in 2019. Our study sought to answer the research question: What are the key factors that contributed to the adoption of wellbeing budgeting in New Zealand?

Policy changes and diffusion occur under the condition of a combination of technical and political factors, all interacting within a political environment. To identify the political factors of this policy adoption, we selected Good’s theoretical framework as it has been influential in conceptualizing the budget actors’ roles and relationships in national budget forms. Although significant, this theory is not often applied to analyze a real budget reform. We investigated the politics of budget reform, in addition to identifying pre-conditions and factors that were present in a larger context to facilitate this innovative policy change.

Our first layer of research findings suggests that Good’s description of the roles of the larger groups of budget actors: priority setters, guardians, and spenders hold true to some extent in the adoption of the wellbeing budget in New Zealand. As one would expect, the priority setters issued directives on budget priorities, guardians ensured that spending met these priorities, and spenders ensured there were ample funds to achieve their own priorities. But, unlike in Good’s theory, budget actors in New Zealand thought beyond their own portfolios, which is different compared to the findings of a Canadian study with education budget actors (Ortynsky et al. Reference Ortynsky, Marshall and Mou2021). In New Zealand, spenders looked for similarities with other ministries, as outlined in New Zealand’s 2019 budget document (New Zealand Treasury 2019), while guardians insisted that all new budget bids be filtered through the wellbeing or LSF. If overlap could be found with other priorities, it is more likely that a spender’s priority would be fulfilled.

In adopting New Zealand’s wellbeing budgets, actors within groups did not necessarily share similar motivations and predictive behaviors as expected by the theoretical framework we used. The largest group of budget actors interviewed were guardians from the Treasury, many of whom were also academics. Within this group, there was a history and pre-condition of eight years of intellectual debate and disagreements on the conceptual framing of wellbeing for New Zealand, how much emphasis should be on the environment versus human wellbeing, and whether the indicators selected could capture progress in an accurate and timely manner. Yet, all guardians were directed to align their efforts to make the LSF operational within Treasury. This was facilitated by the politics of a newly elected Prime Minister who could communicate and take the work that had already been done to new levels and audiences.

Regardless of internal group tensions, all were reaching towards the budget’s five main priority areas: mental health outcomes, child poverty, Māori and Pacifika issues, the environment, and increasing labor productivity and innovation. We found that tensions within the guardian group were evident, and tensions also existed between the two priority setters interviewed, who belonged to different political parties. Therefore, when applying Good’s theory of the politics of local budgeting at the national level, analyses can consider tensions amongst groups of budget actors and within.

In establishing New Zealand’s wellbeing budgets, guardians (the Treasury) have played a larger role than the other two groups, given our sample of interview participants. Since the Treasury has been home to guardians, academics, spenders, and intricately connected to the OECD for over a decade, this has facilitated rigorous debate and innovation within the Treasury itself. The financial constraints of the 1980s led to the amendments of the Public Finance Act. Since then, New Zealand’s budget trajectory has legalized accounting for outcomes, which has evolved into four iterations of wellbeing budgets. When budget actors are motivated by fiscal restraints, by legislation to budget for outcomes, and by an ongoing connection to research, there is a strong potential for innovation within the public sector. This is another pre-condition that leads to the adoption of a performance-based wellbeing budgeting approach.

The ability to account for wellbeing, in terms of which policy leads to which outcomes, is still being refined around the world. The 2009 Stiglitz-Sen-Fitoussi Commission (OECD 2018) provided the rationale for moving away from GDP as the sole indicator of a nation’s progress in a 292-page report. As Guardian 9/Academic 4 argued, there is more empirical backing required to determine exactly which investments improve which wellbeing outcomes and by how much. They referenced the 800-page work by Simon Kuznets as the basis to calculate the GDP in the USA and which has served as the basis measurement of this indicator (Dickinson Reference Dickinson2011) and described how a similar work must be done for wellbeing indicators. To develop indicators that would track the measurement of wellbeing like this with the same analytical rigor that is applied for GDP measures requires ongoing empirical research. How best to measure wellbeing in New Zealand with available public data is still being debated.

We would categorize both Sir Bill English and the Treasury challenge group as policy entrepreneurs: Bill English from his days in Treasury as a bureaucrat, to Finance Minister with the National Party government, and to Prime Minister for championing the approach that has become known as the wellbeing budgets. One guardian, who worked with the Social Investment Agency, said that what English did well was “capture the wellbeing impact of social housing and how much it costs,” adding, “one of the brilliant things that English did was he got Statistics New Zealand to actually create a research data set that looked at the individual level.” Coming from a more fiscally conservative background than the current party in power, this guardian knew that good, evidence-based social service investments have the potential to move people out of poverty to a place where they could contribute to the economy rather than relying on public services. The Treasury challenge group was able to create an LSF with both internal and external influences on government.

New Zealand’s overall approach to government and its strong public sector management culture played a significant role in the development of innovative policy, government processes, and performance-based budgets. It is evident that certain developments over history have impacted the present-day adoption of four wellbeing budgets. The objective of reaching consensus even with prior rigorous debate can lead to budgeting process reforms and outcomes. Therefore, New Zealand has approached its budgeting process with a holistic mindset, one that considers human welfare, environmental considerations, and targets that have been set. These budgeting reforms have withstood a three-decade long evolution and are greater than the individual and specific priorities of any political party.

Other factors present in the New Zealand context that may have facilitated the adoption of the wellbeing budgeting approach include constraints of natural resources, geographic isolation, a small population, only two levels of government (central and local governments) and a three-year election cycle. These factors may have provided parameters that have fostered innovation and public sector management. Lastly, international policy diffusion played a role in the adoption of this budgeting approach.

Conclusion

This study identified factors that facilitated the adoption of New Zealand’s innovative wellbeing budgeting approach. Significant budget reform is a rare occurrence and therefore public sector culture, consensus-building, a pre-condition of performance-based legislation, and an influential larger political context all facilitated this policy change. Our research provides insights that countries and authorities interested in pursuing a similar budgeting approach can learn from and improve upon when pursing their own budget reforms and public sector outcomes

We found in our research that politics are beneficial – tensions between groups of budget actors and within guardians can be leveraged to debate differing approaches that lead to consensus on the goal of budget reform. Wellbeing budgetary and other types of budget reform may be undertaken with a combination of legislation, fostering a public sector culture of debate, and responding to the larger context of global conditions of uncertainty.

These were all key conditions to the adoption of New Zealand’s wellbeing budgeting approach. Findings from our interviews show that the country’s budgeting evolution can be traced to collaborative relationships among budget actors, robust performance-based management within the Treasury; the encouragement of ministries to move outside their silos and take ownership of the LSF as it applied to their programs and policies; and, in its most recent wellbeing iterations, a focus on wellbeing promoted not only within New Zealand but also around the world.

What makes the New Zealand case unique is the politics between groups of budget actors and within groups, differing from Good’s (Reference Good2007) framework, which stipulates the distinct interests and incentives of major groups of budget actors. External influences such as the OECD and academic schools of thought were also present. New Zealand’s relative isolation, and a culture that embraces a willingness to try ideas aided in the development of this budgeting approach. As a result, the Treasury and government have refined the social investment approach and produced budgets based on the wellbeing of the country’s citizens. This commitment to wellbeing, regardless of which political party is in power or how this commitment is communicated, has endured over several electoral cycles.

Wellbeing budgeting in its full expression cannot be accomplished within an electoral cycle or even in one or two terms in office. Wellbeing budgets in New Zealand have brought together politicians and political parties from both sides of the divide to support one common approach. Although they may disagree about the specifics and how data are used in decision-making, this evolution in public sector budgeting has accomplished a move, however small, away from measuring New Zealand’s progress only in economic metrics such as GDP.

Significant budgetary reform takes time unless it is instigated by a crisis (Baumgartner and Jones 1999). To move the status quo, economic distress is a great motivator (Fabrizio and Mody Reference Mody2010). In New Zealand, budgetary innovation was sparked by economic woes, the financial reforms of the 1980s. In addition, the reform was facilitated by collaboration across ministries and a willingness to try novel approaches and adjust courses. New Zealand’s wellbeing budgets are an evolution of a performance-based budget decades in the making. Other jurisdictions considering adopting a performance-based budgeting system need to be aware of challenges: the cost of data collection, difficulties with performance measurement, culture shifts required from budget actors, and the need for agreement about outcomes.

There were sampling limitations in our study. In this research, we only interviewed two priority setters. If we had interviewed more, the response to questions about the public’s influence on the adoption of wellbeing budgets might have been different. Even though we reached out directly to each minister’s office, recruiting decision-makers proved to be unfruitful during the pandemic (winter, spring, and summer of 2021). With our sample, we were able to interview academics and Treasury officials who had been part of the initial conceptualization and creation of the LSF and subsequent wellbeing budgets. We were surprised to encounter a revolving door of the country’s brightest academic minds who move from government to universities in New Zealand, Australia, and the UK. We found most participants forthcoming and frank in their interviews with us. Another drawback with this sample was that ministries that had adopted the wellbeing approach were more likely to self-select or be recommended to me as someone who might agree to be interviewed. This meant that we did not interview anyone from ministries who may have been struggling with the wellbeing budgeting approach.

Although budget processes in most countries are stable and incremental, significant budget reform is possible because of an external shock to the system or changing contexts. Any jurisdiction aiming to adopt a similar wellbeing budget, or a new budgeting approach must consider the following: using broad government goals to motivate budget actors to collaborate and achieve outcomes, possibly through cultural and legislative changes; motivating all groups to explicitly communicate their wellbeing budgeting approach to broader public; and ensuring that cooperation occur not only between groups of budget actors but also within groups of guardians and spenders.

Data availability statement

This study does not employ statistical methods, and no replication materials are available.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the interviewees who participated in our study. The authors sincerely thank all those who read, provided edits and commented on several versions of this paper: Cheryl Camillo, Jim Marshall, Joanne Marshall, Heather McWhinney, Keith Walker, and Yang Yang.

Funding statement

This study is supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) of Canada, Insight Grant, held by Principal Investigator Haizhen Mou and co-applicant Michael Atkinson.

Competing interests

There is no conflict of interest.