Introduction

Since the mid-1980s, the Spanish labor market has registered by far the highest rate of fixed-term contracts among Western countries. With rates that range between 25 and 34 percent of total employment in the last three decades, Spain has more than doubled the average for the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries. Thus, the “Spanish anomaly” has attracted the attention of researchers to understand the causes behind the high incidence of this type of employment in Spain across the decades and in comparison to other countries.

Although interpretations of this phenomenon are varied, the flexibilization reforms started in the mid-1980s are often understood as the beginning of this dynamic and the formation of one of the most extreme examples of a two-tier labor market among OECD countries either because of the differential levels of protection against dismissal (Polavieja, Reference Polavieja2006) or as a result of policies that shaped the temporary work culture among employers (Toharia, Reference Toharia2005). Labor policy and labor market functioning in this decade are seen as a crucial turning point in the history of Spanish labor markets.

According to this view, the explosion of temporary contracts during the 1980s represented a critical discontinuity with the preceding Francoist labor market, generally characterized by its rigid institutions and functioning. The dictatorial regime was seen as having extensively limited any means of external numerical flexibility: promoting a high degree of employment protection against the dismissal of permanent workers and severe restrictions on the use of temporary contracts. At the time of Franco’s death, temporary employment represented a very small proportion of the working population. Thus, internal numerical flexibility, mainly due to overtime, and financial flexibility, through the extensive use of multiple types of additional payments, were seen as the main mechanisms of flexibility during the dictatorship (Serrano and Malo de Molina, Reference Serrano and Malo1979; Dolado, García-Serrano and Jimeno, Reference Dolado, García-Serrano and Jimeno2002; Toharia, Reference Toharia2002).Footnote 1

However, the lack of available data has hindered a full and empirical understanding of the role of temporary employment during Franco’s dictatorship and its long-term legacy (Banyuls and Recio, Reference Banyuls, Recio, Damian, Colette, Gail and Távora2017). This article revisits this historical episode using an array of known and novel information and assesses the incidence of fixed-term contracts and other forms of flexible employment across branches, occupations, and cohorts from 1959 to 2019.

It constitutes the first empirical and representative study covering all sectors of the Spanish economy. In this regard, this article contributes to the literature by reframing how rigid labor institutions, labor market functioning, and management practices were during this period. It analyzes the role of numerical external flexibility in all its typologies, with particular attention to fixed-term contracts. As is well known, this type of contract has been at the center of the academic and political debate on the dysfunctionality of the Spanish labor market in recent decades. In addition, the role of these management strategies is assessed in comparison with the main alternative management strategy presented in the literature: overtime. It also sheds light on the origins of the gap in temporary employment rates between Spain and other European countries. To do so, it compares Spain with countries that shared similar labor market institutions since the mid-1980s and were considered two-tier labor markets during all or part of this period – namely, France, Germany, and Italy (Emmenegger, Reference Emmenegger and Oude2021).

The study of temporary employment during the late Franco dictatorship is important for three reasons. First, as a crucial period in Spain’s modern history, its labor market legacy has shaped key debates on the Spanish labor market today. These include fundamental issues such as the impact of the labor reforms conducted since the return of democracy, the sociological origins of external numerical flexibility in Spain, and working conditions and labor market policy during Franco’s dictatorship (Toharia, Reference Toharia2005; Babiano, Reference Babiano and Ortiz2005; Sola, Reference Sola2014; Sánchez-Mosquera, Reference Sánchez-Mosquera, Sánchez-Mosquera and Gutiérrez2022).

Second, visions of the functioning of the labor market during this period have played an important role in understanding the “Spanish anomaly.” Third, from a broader perspective, this article sheds light on the prevalence and role of temporary employment in post-war Europe and the heterogeneous levels of incidence across Western economies. As such, this article is in line with previous studies, such as Betti and Vernon that address the potential continuities between the Fordist and post-Fordist periods (Betti, Reference Betti2018; Vernon, Reference Vernon2021). As Betti argues, this is particularly relevant to our understanding of post-war labor precariousness and women’s participation in labor markets and social movements during this period.

The “Spanish anomaly” on temporary employment

In the late 1980s, Spain registered high and growing rates of temporary employment. The share of workers with fixed-term contracts skyrocketed from 17 percent in 1987, the first year with official records, to 34 percent in 1992. The incidence of these forms of employment was particularly prevalent among young workers and women, a common characteristic of the two-tier labor markets.

Economists have long discussed the explanatory factors of the high rate of temporary employment in Spain since the mid-1980s. The prevalent view remarks on the crucial role of the 1984 labor reform as the beginning of the two-tier labor market. According to these researchers (Dolado, García-Serrano, and Jimeno, Reference Dolado, García-Serrano and Jimeno2002; Polavieja, Reference Polavieja2006), the interaction between the different levels of protection of permanent and temporary contracts established by this law and unemployment shocks can explain the differences with other countries. The labor reform established that while dismissing a permanent employee costs 45 days’ wages, dismissing a temporary employee costs 12 days’ wages. It also allowed the use of fixed-term contracts for up to 3 years for any type of job. During the mid-1980s and early 1990s, Spain experienced the entry of baby boomers into the labor market and a high unemployment crisis, which reached 20–25 percent. Thus, the combination of strong employment protection for permanent workers and high unemployment provided strong incentives for employers to resort to temporary work, taking advantage of the large labor supply and the greater willingness of workers to accept temporary contracts in the face of high unemployment.

In this regard, the literature has traditionally considered the 1980s as a crucial turning point, marking a discontinuity between the Franco dictatorship and the democratic period. Historians and economists have argued that the labor market during the Franco period was characterized by its low levels of labor flexibility and rigid labor institutions (Serrano and Malo de Molina, Reference Serrano and Malo1979; Molinero and Ysàs, Reference Molinero and Ysàs1998; Babiano, Reference Babiano1998; Vilar, Reference Vilar2009). Researchers have also concluded that the Spanish dictatorship compensated for the ban on trade unions and the lack of political freedoms by offering a rigid labor market with high employment protection. The dictatorship thus shaped labor market dynamics that achieved lifelong job stability and security for workers. Therefore, in 1975, at the end of the dictatorial regime, the level of temporary employment was seen as being below 10 percent of total employment (Dolado, García-Serrano, and Jimeno, Reference Dolado, García-Serrano and Jimeno2002; Toharia, Reference Toharia2002).

The labor market in the decade of the 1960s and early 1970s was severely restricted by the institutional framework established by the Franco dictatorship. Political and trade union associations were illegal, and workers were obliged to belong to the sole trade union, the Organización Sindical Española. Working conditions were regulated by sectoral laws set by the state. From 1958, wages were set through collective bargaining under the control of the dictatorship. The regime was able to intervene to control these wages and often used the minimum wage as a tool to keep wage growth down. Labor legislation promoted internal labor markets within a hierarchical work structure typical of the Fordist conception of management. Tenure and internal promotion were granted, while the dismissal of permanent workers, although free for disciplinary reasons, was particularly costly (Fina, Meixide, and Toharia, Reference Fina, Meixide, Toharia and Rosenberg1989; Babiano, Reference Babiano1998; Vilar, Reference Vilar2009).

In this institutional context, economists and historians have concluded that firms sought mechanisms to achieve certain necessary levels of flexibility on both wages and labor. They implemented two main management strategies that focused on the internal adjustment of their core workforce: extra payments and overtime work. Firms introduced various types of official and unofficial extra payments, such as performance bonuses, subsidies, and payments in kind, among others, to compensate for the low wages set by collective agreements and to reward the skills and hard work of their employees, and when they had to temporarily increase production levels, they increased the number of hours worked instead of hiring new employees. According to this view, overtime work was a cheaper and more flexible source of labor than hiring new employees, since the costs of dismissal were very high. Therefore, given the high cost of dismissals, the prominent management strategy to cope with temporary needs for labor was numerical internal flexibility through the widespread use of overtime work (Serrano and Malo de Molina, Reference Serrano and Malo1979).

However, some authors have hypothesized that external numerical flexibility may have played a role in Franco’s labor market. These researchers hypothesize that the high rate of fixed-term contracts in the first official survey conducted – 17 percent in 1987 – could hypothetically indicate that external numerical flexibility was already part of the management practices of sectors that were particularly important in Spain during the dictatorship, such as agriculture, tourism, construction, and work performed mainly by women in domestic service and some industrial activities (Banyuls and Recio, Reference Banyuls, Recio, Damian, Colette, Gail and Távora2017). Others such as Sola (Reference Sola2014) note that Spanish democracy could have inherited a model of industrial relations based on the subordination of workers, which could include greater employment flexibility.

From a historical perspective, Babiano has argued that temporary employment could still have been an important source of labor during the 1940s and 1950s despite the rigidness of the labor market. However, during the 1960s and early 1970s, permanent contracts would have become the norm (Babiano, Reference Babiano and Ortiz2005). Similarly, Toharia considered that there was a certain prevalence of fixed-term contracts in some seasonal sectors such as tourism, agriculture, construction, or the food industry. However, the courts and the labor movement managed to reduce fixed-term contracts significantly during the 1960s and early 1970s. As a result, this author points out that in the two sectors in which they have data, temporary employment in construction and food industries with more than 10 employees could have been over 30 percent in the early 1960s while in 1976 it reached 15 percent (Toharia, Reference Toharia2002).

Sources

The study of the different forms of temporary employment before the 1980s, and in particular the use of fixed-term contracts, is challenging given the lack of official accounts registering these forms of work. As Beau (Reference Beau2004) notes, the late 1970s is not the origin of temporary work but rather the first period in which it began to be registered and made visible. Moreover, the general under-reporting of women’s work in official statistics also contributes to the invisibility of some forms of flexible employment (Humphries and Sarasúa, Reference Humphries and Sarasúa2012; Betti, Reference Betti2020).

To address this issue, this article draws on a wide range of data on different forms of temporary employment in the 1960s and early 1970s. These data come from reports, national statistics, and archival work. As shown in Table 1, the share of fixed-term contracts in Spain is examined using sources familiar to social scientists but not previously used for this purpose. All these sources are the result of an extrapolation of the Spanish working population for different years, comprising 20–25 percent of the Spanish workforce. To assess this share at the beginning of the 1960s, the reports from the Comisaría del Plan de Desarrollo Económico y Social de España provide detailed data. This information was part of the indicative planning policies of the Spanish dictatorship. To evaluate these levels in the early 1970s, I take into account the data on temporary work reported in the 1970 Spanish Population Census and 1975 Spanish municipality registers.

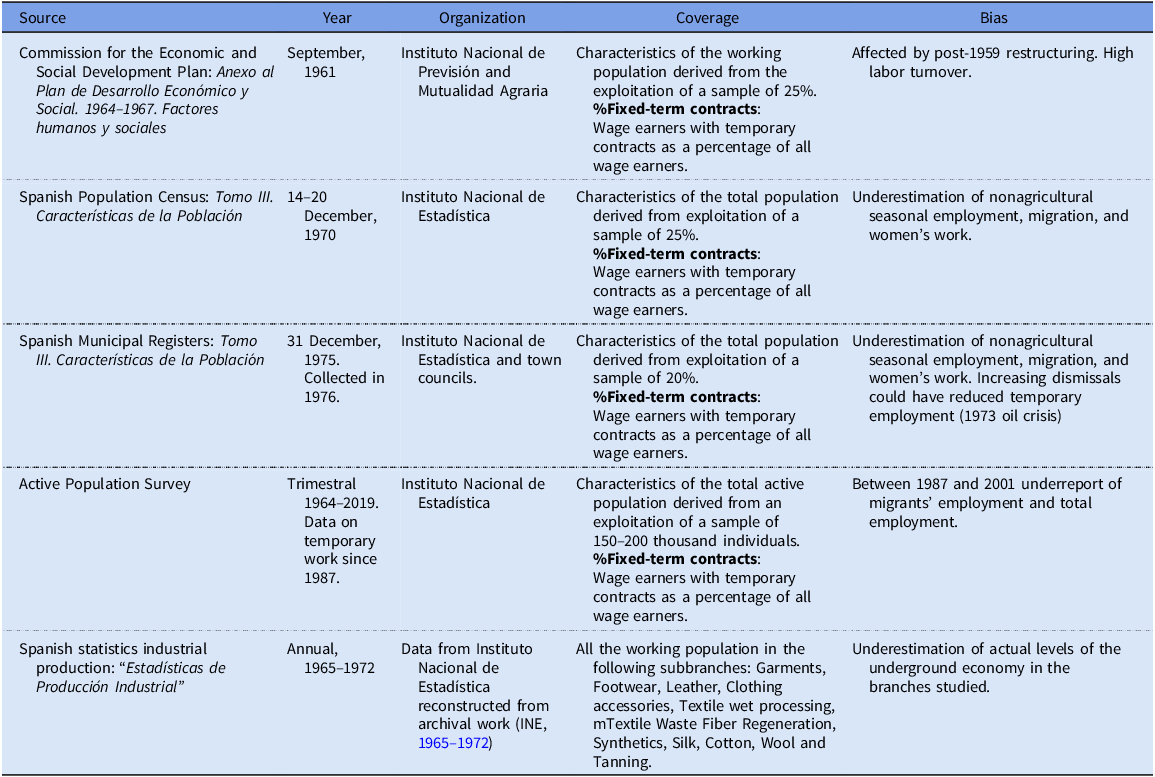

Table 1. Main sources

These data are linked to the official accounts of the Spanish National Statistical Institute (INE) since 1987. This information is also supplemented by internal reports and data from the archives of the Organización Sindical, the only legal Spanish trade union, controlled by the dictatorship, and the Spanish National Statistical Institute. It includes data on labor management and other forms of temporary employment, such as some typologies of outsourcing, self-employment, and home work. Finally, to enrich the results, I additionally drew on qualitative and quantitative sectoral and business historical studies from academic literature.

A similar approach was conducted to analyze Spanish temporary employment and the institutional framework from an international perspective. Firstly, the article uses multiple pieces of legislation from Spain, France, Germany, and Italy from their respective legal corpora. Secondly, their official accounts from enquêtes employ by the Institut National de la Statistique et des Études Économiques (INSEE), in France and data from Bundesanstalt fur Arbeit in Germany. Furthermore, due to the characteristics of the Spanish labor regulation, sectoral labor regulation of selected sectors over the period 1964–1973 is also examined. As well as in the Spanish case, estimations using these sources were conducted to overcome some of the issues related to the lack of available data. Table A.8 in Supplementary Materials shows the procedures implemented.

Although the core data come from Spanish official statistics, they still suffer from certain shortcomings (Table 1). Information from Comisaría del Plan de Desarrollo Económico y Social de España (CPDES), is affected by the restructuring process initiated by the Spanish Stabilization Plan in 1959. Between 1959 and 1962, firms adapted to the opening in trade and financial terms of the Spanish economy and anti-inflationary measures launched by the Plan. As a result, unemployment doubled, migration to European countries intensified, and the number of strikes increased, particularly in the mining sector (Soto, Reference Soto2006). Therefore, as turnover rates were significantly high in the majority of branches of the economy, the share of fixed-term contracts could reflect the impact of this process on temporary workers, those that could be more easily dismissed by employers.

Conversely, information from the 1970 Spanish census depicts the characteristics of the Spanish workforce in a period of solid economic performance. Thus, the main biases of this source are related to seasonality and potential underrepresentation of women’s work. On the one hand, data were collected in December 1970, the period with lower temporary employment in most nonagricultural sectors as a result of the higher involvement of this employment in the rest of the year (Ministerio de Trabajo, 1965; Cachón, Reference Cachón1995; Silvestre, Reference Silvestre2007). This bias can also be seen in the discrepancies between the unemployment rate reported by the 1970 Census and other sources. While the 1970 Census reports 372,698 unemployed in December, the 1970 Economically Active Population Survey collected in the second semester registered a total of 144,100. Additionally, in regions that substantially relied on temporary migrants, this bias could be particularly important since the Census would not capture the stay of these migrants in the municipality for two main reasons. First, the peak of labor demand in the sectors reliant on temporary migrants may not have coincided with the period of the Census interviews (Silvestre, Reference Silvestre2007). Second, even though the interviews took place during the stay of the migrant, most could not be interviewed.

The 1975 Spanish municipal registers are also biased by this effect. However, they show levels of temporary employment in a period marked by labor and political conflict derived from the fight against Franco’s dictatorship and the 1973 oil crisis. In this respect, unemployment and dismissals started in some branches in 1974. As the data were collected at the end of 1975, it could capture the first dismissals that were likely to be concentrated on temporary employees who were easier to fire.

Furthermore, these data could misrepresent women’s participation in the labor market. Bureaucrats, enumerators, and householders tended to assign them to occupations related to the reproductive economy. This could also negatively bias temporary employment since women were proportionally more involved in seasonal and irregular work activities than men (Humphries and Sarasúa, Reference Humphries and Sarasúa2012).

The data from the Spanish Active Population Survey since 1987 come from the same statistical body and also include the proportion of wage-earners with a temporary contract at the time of the interview. However, there are two main differences with the other sources, especially the census data. Firstly, the data from the Spanish Active Population Survey come from the use of a smaller sample that includes interviews with 62–65 thousand households representing 150–200 thousand individuals, depending on the year of the interview. Secondly, this source may cover a higher proportion of seasonal employment, as well as work done by women and internal and international migrants. The modernization of both statistical institutions and society since the 1980s could potentially imply a higher level of coverage of women’s work and migrants’ employment. Moreover, the seasonal evolution of employment could be better captured by the quarterly survey.

Therefore, it is important to bear in mind that the data used to construct the following series have been subject to different methodological approaches depending on the year in question, particularly concerning the seasonality of employment. However, as they all focus on the same variable – i.e., the share of employees with temporary contracts – these series are very useful for analyzing, with the necessary caution, the long-term evolution of temporary employment in Spain. For this reason, the main focus of the article is on the degree of prevalence of temporary employment and related management practices during the late Francoist period. Although the evolution of fixed-term contracts present in the data is analyzed, conclusions are based on the general assessment of these practices over the whole period.

Finally, to study home work, I rely on data from the textile and footwear industry from Spanish industrial statistics, Estadísticas de Producción Industrial (Table 1). This is the sector that has historically been more associated with this type of work. The official data do not disaggregate the share of payments made in the factory and at home, as this information is considered confidential. In this article, I present new data on home work from archival work on this source by reconstructing this information, which allows me to estimate the proportion of home work in each sub-sector of this industry. Although firms may have deliberately understated their total payments for home work to the authorities, the results presented in this article suggest that home work was a very important part of their management strategies and total payments.

Temporary employment in Spain: a historical perspective

Fixed-term contracts in Spain since 1959

The 1959 Stabilization Plan marked a turning point in the Spanish economy. The liberalization reforms implied a process of restructuring, which triggered the completion of the industrialization process and structural change. Therefore, starting from 1961 is particularly appropriate as this process could create a significant path dependency on the management strategies of firms. Using the new sources mentioned above, we can trace the evolution of fixed-term contracts in the long run from this crucial process to the present day.

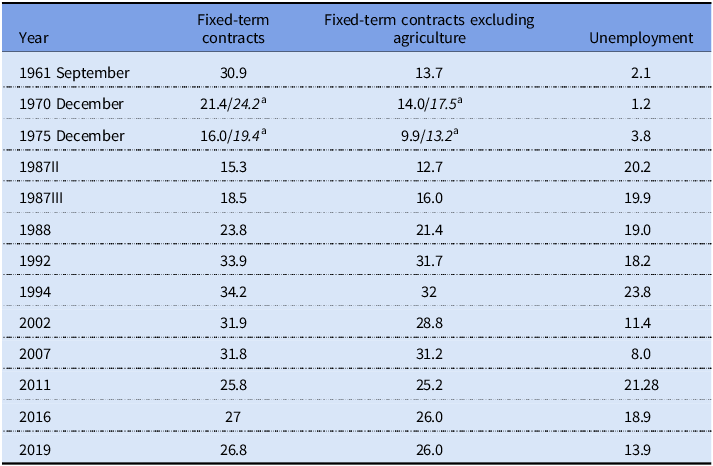

During this period, the proportion of fixed-term contracts was dramatically higher than usually assumed. Although the widespread use of permanent contracts and the stability of careers were an important part of the rhetoric and propaganda of the dictatorial regime (Babiano, Reference Babiano and Ortiz2005), the share of fixed-term contracts in total employment was 30.9 percent in 1961 and fell to 21.4 percent in 1970. As hypothesized by Toharia (Reference Toharia2002), temporary employment continued to decline to 16 percent at the end of the dictatorial regime (Table 2).

Table 2. Fixed-term contracts in Spain, 1961–2019 (%)

Source: CPDES (1963); 1970 Spanish Population Census; 1975 Municipality Registers; Fundación BBV (Reference Fundación1999); Fundación BBVA (Reference Fundación2007).

Note: Estimates in italics. 1988–2019 third semester.

a Includes seasonal workers in the services sector, defined as the difference between the 1970 census, which was collected in December, and the annual average of the number of workers in the sector in the same year.

However, the decline of temporary employment between 1961 and 1970 can be associated with the evolution of the agricultural labor market and seasonality. While September – the month of 1961 data – is associated with two main peaks of agricultural labor demand, cereals, the most numerous at that time, and vineyards – December is mainly only related to the olive harvest. Furthermore, the decline of labor supply under the context of the rural exodus and its subsequent intense mechanization of seasonal jobs implied a considerable decrease in fixed-term contracts although very high temporary employment continued to be prevalent (Naredo, Reference Naredo2004). Indeed, a significant part of the incidence of fixed-term contracts is related to the importance of agriculture in the Spanish economy and the high degree of job instability in this sector. Thus, after excluding agriculture, temporary employment is lower but still substantially significant, and that explains the higher temporary employment in all sectors in 1961 compared to 1971. As a result, the share of such contracts in industry and services was much lower, although still very significant, at 13.7, 14.0, and almost 10 percent in 1961, 1970, and 1975, respectively. Just over a million workers were on fixed-term contracts in services, construction, and industry combined, compared with six million forty thousand on open-ended contracts in 1970.

Similarly, the data on service and industrial employment could also underreport the seasonal and temporary work that took place during the rest of the year (Table A.1 in Supplementary Materials).Footnote 2 To partially address this issue, this gap has been estimated by looking at the difference in the services sector – the most downwardly biased by the Census methodology – between the Census and the annual average reported by Fundación BBV (Reference Fundación1999). This estimate suggests that temporary contracts could have accounted for 24.2 percent and 19.4 percent of total employment in 1970 and 1975, respectively, and 17.5 percent and 13.2 percent if agriculture is excluded. Consequently, the percentage of fixed-term contracts was higher than those reported for the first time by the official accounts in 1987 and similar to 1961.

In the aftermath of the 1973 crisis, between 1975 and 1984, a period of major changes in the Spanish labor market was witnessed, characterized by rising unemployment and high levels of political and labor unrest in the context of the transition to democracy. Along with the achievement of union and political freedoms significant labor reforms took place. After Franco’s death, under a weak dictatorial government, the Labor Relations Act of 1976 represented a step forward in favor of the regulation of temporary employment and labor stability. This law abolished the possibility of dismissing permanent workers at will with costly compensation, which had characterized Spanish labor relations since 1959 and implied a legal preference for permanent contracts. Both measures aligned with labor law in most democratic countries (Sánchez-Mosquera, Reference Sánchez-Mosquera2021).Footnote 3

Between 1976 and 1981, fierce opposition from employers, who demanded greater labor flexibility in a context of crisis, led to the return of costly free dismissal and the gradual flexibilization of temporary contracts through new labor regulations (Cárdenas, Reference Cárdenas2023; Malo, Reference Malo2005).Footnote 4 Indeed, researchers have shown that employers’ organizations promoted the idea that the labor market inherited from Franco’s dictatorship was characterized by a lack of labor flexibility, particularly external numerical flexibility. Building on this idea, they lobbied heavily to increase the legal flexibility of the use of temporary contracts and to reduce the costs of dismissals under permanent contracts (Flores-Andrade, Reference Flores-Andrade2002; Sánchez-Mosquera, Reference Sánchez-Mosquera2021). However, as Sánchez-Mosquera (ibid.: Reference Sánchez-Mosquera2021) explains, the initial weakness of employers’ organizations and especially the absence of a government committed to the flexibilization of the labor market meant that a radical change in the use of temporary contracts did not take place until 1984. The impact of the 1984 labor reform in interaction with the unemployment crisis on fixed-term contracts substantially exceeded the pre-democracy rates by 1989. By 1992, these contracts were already significantly higher than in 1961, 1970, and 1975.

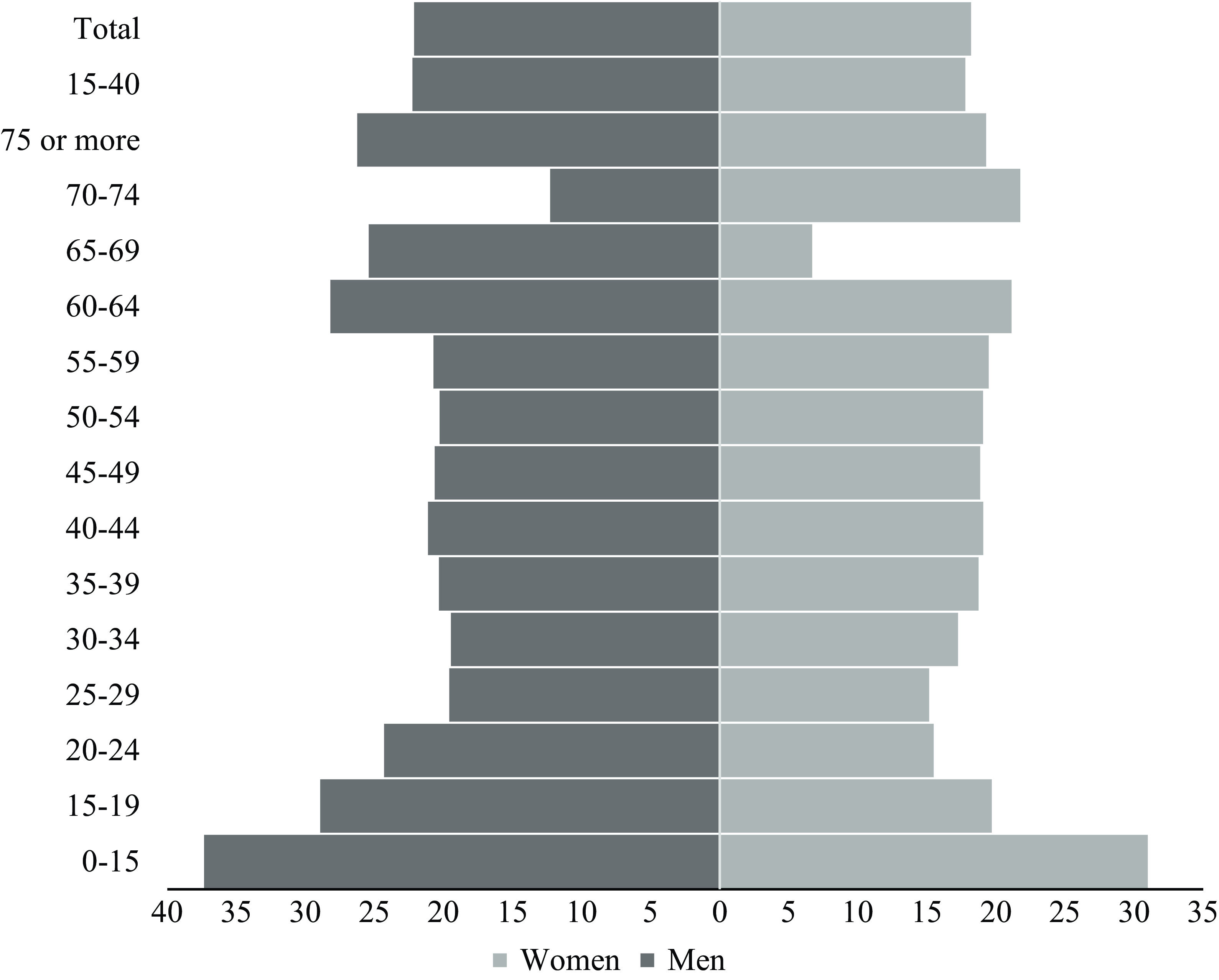

The groups of workers more exposed to these flexible arrangements were young workers and women. As Figure 1 shows, in 1970, the share of fixed-term contracts was 35.1 percent for those aged under 15 (the legal working age was 14). Similarly, 25.5 percent and 21.21 percent were recorded for workers aged 15–19 and 20–24, respectively. However, as in 1970, agriculture employment comprised a significant share of total employment; these results are considerably biased. To partially solve this shortcoming, Table A.2 in Supplementary Materials examines the prevalence of agricultural employment among cohorts and genders. This exercise suggests the share of temporary employment related to the agricultural sector was much lower among young workers and women than among older men and women, indicating that nonagricultural flexible employment was significantly higher among both groups.

Figure 1. Fixed-term contracts in Spain by age and gender in 1970 (%).

Source: 1970 Spanish Population Census.

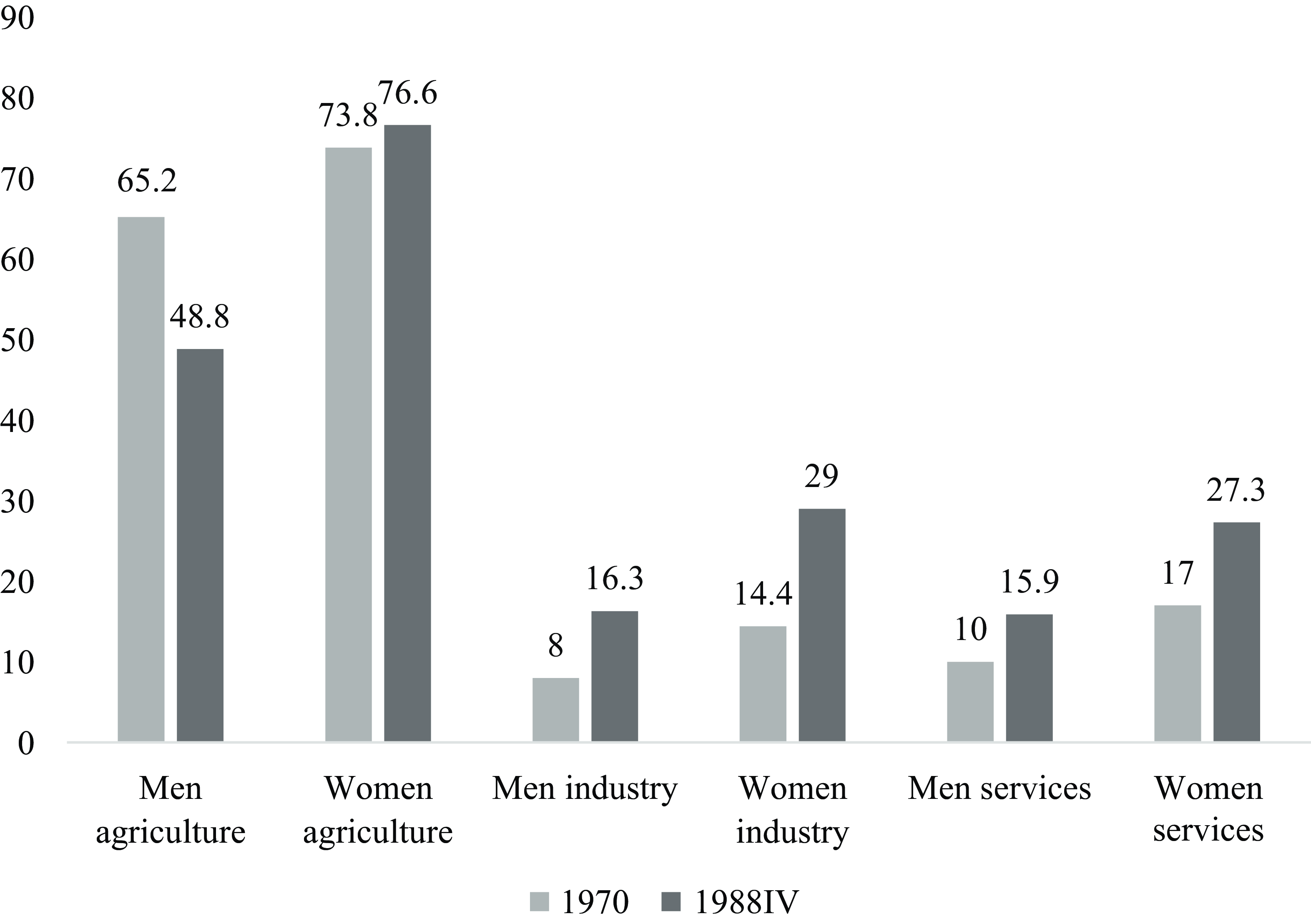

This is particularly relevant when it comes to women’s work, and young women in particular, the group of workers with lower participation in agricultural employment in the Census and one of the most exposed to flexible employment: women between 15 and 25 years old registered more than 20 percent of fixed-term contracts despite their very low exposition to the agricultural sector (Figure 1 and Table A.2 in Supplementary Materials). As Figure 2 shows, women were more prone to having a fixed-term contract in all economic activities in both 1970 and 1988.

Figure 2. Share of fixed-term contracts by gender in industry (construction excluded) and services, 1970 and 1988.

Source: 1970 Spanish Population Census; Instituto Nacional de Estadística. 1988 Economically Active Population Survey.

It is important to mention that the 1970 results are shaped by Francoist legislation and its sociocultural context. Franco’s labor and political legislation, as well as the regime’s propaganda, pushed women out of the labor market. In particular, the dictatorship established mechanisms to discourage women’s participation in the formal labor market. It restricted access to certain careers, imposed the exit of women after marriage – since the 1960s, married women could work but only under marital authorization – and promoted a whole series of salary bonuses conditional on the mother’s full dedication to reproductive work – fundamentally, caregiving and domestic housework – which were vital in a context of high levels of poverty and low wages. This favored the higher involvement of women in temporary employment but also in the informal labor market. Thus, as will be analyzed below, the rates of temporary employment among women would be even higher once considering the actual female activity rates by including the informal sector in which women played a key role (Vilar, Reference Vilar2009; Sarasúa and Molinero, Reference Sarasúa, Molinero and Borderías2009).

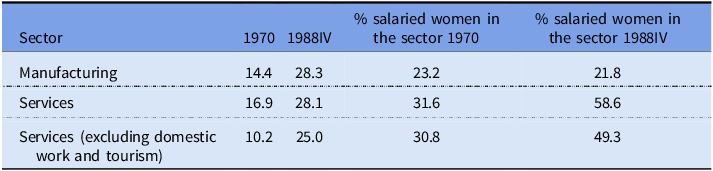

Indeed, the role of women’s work as a source of flexible employment for firms in some manufacturing and service subbranches was crucial. Women comprised an important share of employment in branches such as retail, health care, tourism, domestic work, education, textile and footwear, food, beverages, and tobacco industries, in which their rates of temporary employment were notably high. Thus, as Table 3 informs, the share of women holding a fixed-term contract was at least 10 percent of total employment, even when we exclude two very unstable sectors: tourism and domestic work.

Table 3. Incidence of women’s fixed-term employment in manufacturing and services, 1970 and 1988

Source: 1970 Spanish Population Census; Instituto Nacional de Estadística. 1988 Economically Active Population Survey.

Temporary employment within branches and occupations

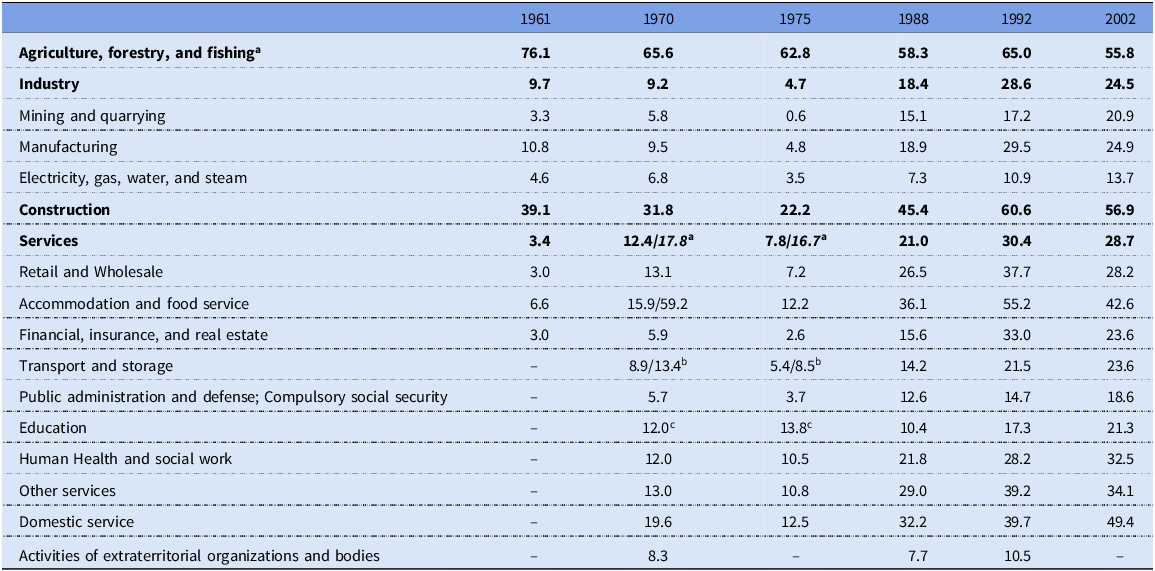

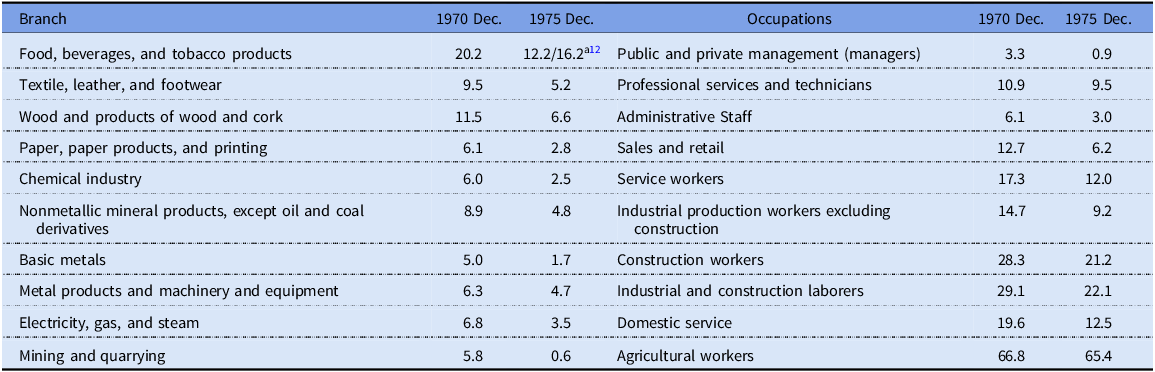

The prevalence of fixed-term contracts in the Spanish economy by branches, subbranches, and occupations is analyzed in Tables 4–7. Table 4 examines the incidence of fixed-term contracts using the economic activity categories defined by the Spanish National Statistics Institute (INE) to follow their evolution between 1961 and 2002. This table shows that in 1970, fixed-term contracts accounted for at least 10 percent of total employment in all the main economic activities. Apart from agriculture, a significant share can be observed in construction,Footnote 5 and to a lesser extent, in services. The impact of the turning point in the mid-1980s led to a sharp increase in almost all sectors. However, in 1970, at a time of very low urban unemployment and economic growth, fixed-term contracts were an important source of labor flexibility.

Table 4. Fixed-term contracts by sector and branch in Spain, 1961–2002

Source: CDPES (1963); 1970 Spanish Population Census; 1975 Municipality Registers; Instituto Nacional de Estadística. 1988–2022 Economically Active Population Survey.

a Includes seasonal workers in services, defined as the difference between the census reported in December and the annual average of the number of workers in the sector in the same year.

b If workers of the state-owned companies, RENFE, Correos y Telégrafos, Telefónica, and Iberia are excluded, considering all their workers as permanent employees.

c Includes the occupational category of male and female teachers of any kind of level of education.

Note: Between 1988 and 2019 agriculture comprises the first trimester and the rest of the sectors report the thrid semester. Estimations in italics.

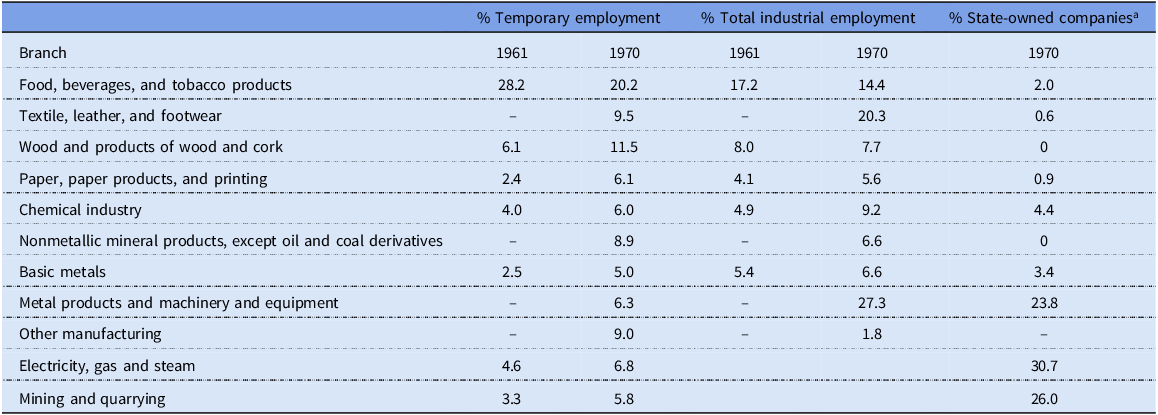

Table 5. Fixed-term contracts in manufacturing, electricity, gas and steam, and mining and quarrying in Spain, 1961 and 1970

Source: CPDES (1963); 1970 Spanish Population Census; Fundación BBV (Reference Fundación1999).

a Personnel from state-owned companies from the National Institute of Industry (INI). Data from Instituto de Estudios Fiscales (1973: 316–321). Estimations in italics.

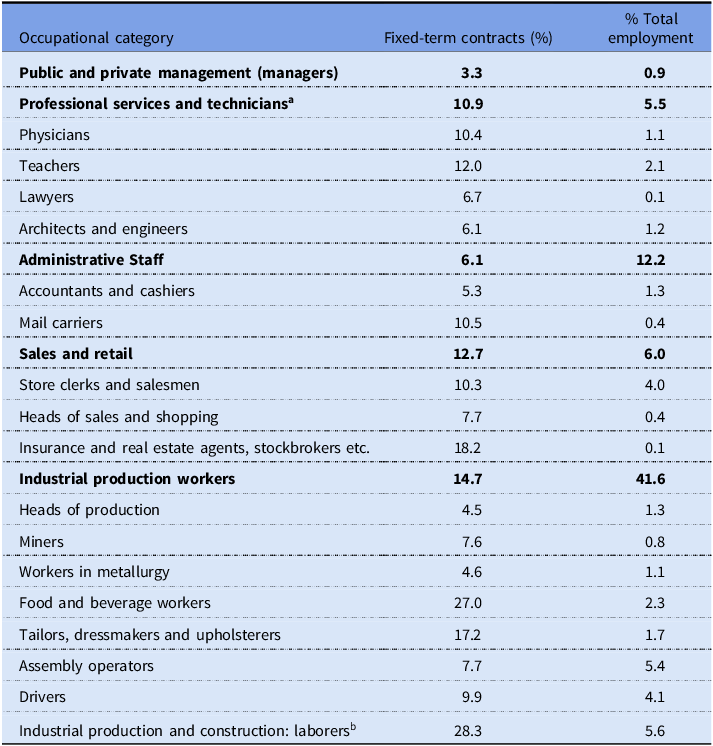

Table 7. Fixed-term contracts by selected occupational categories, 1970

Source: 1970 Spanish Population Census.

a It does not include personnel from clergy and religious orders.

b It excludes occupations directly related to the construction sector.

Fixed-term contracts were widespread in the services sector in branches such as accommodation and food services, education, human health and social work, domestic services, transportFootnote 6 and storage, and retail and wholesale. It is important to note the high incidence of such employment in accommodation and food service, given the emerging importance of tourism in Spain during this period. The high seasonal bias of the census data (collected in December) makes it difficult to provide a complete picture of workers in this sector and others, particularly seasonal ones such as retail and transport. However, data from the high season in 1969 in the Balearic Islands, the epicenter of the Spanish tourism boom, show that temporary contracts accounted for more than 50 percent of total employment in this service industry, involving a large flow of circular internal migrants (García-Barrero, Reference García-Barrero2024).

Within manufacturing, the role of fixed-term contracts differed markedly between branches (Table 5). In some volatile and key branches, such as food, beverages and tobacco, the share of fixed-term contracts reached 10–20 percent.Footnote 7 , In textiles, leather and footwear fixed-term contracts accounted for 9.5 percent of total employment. The share of fixed-term contracts was even lower, although significant, in other stable industries with large-scale production, such as chemicals, basic metals, and machinery and equipment. However, as in the cases of transport and storage activities, the significant role of state-owned companies – particularly in mining, electricity, gas and steam, and metal products and machinery and equipment – implied that flexible employment in the private sector could be higher than shown in Table 5.Footnote 8

It is also worth noting the increase in fixed-term contracts across the majority of sectors and industries between 1961 and 1970, even taking into account the potential seasonal bias of the 1970 Census. Indeed, the only sectors showing a decline are traditional seasonal sectors such as the food industry and textiles, leather, and footwear, where seasonality and production levels depending on the year and month may mean that temporary employment in these sectors could have been even higher or similar to 1961 levels.Footnote 9

Therefore, the growth of temporary employment seems consistently explained as the effect of the countercyclical pattern of employment between 1959 and 1973. In many industries, the lower level of temporary employment in 1961 could have been mainly a direct consequence of the restructuring process initiated by the 1959 Stabilization Plan. As Table 6 shows, labor turnover was remarkably high in the years following the start of the restructuring. The regime relaxed the dismissal laws for permanent employees in 1958 to facilitate the restructuring of enterprises (Malo, Reference Malo2005). Thus, although the new regulatory framework meant that permanent workers were dismissed at a higher rate than in previous periods, temporary workers were dismissed much more easily and probably more extensively – because their contracts expired and were not renewed as a result of the economic crisis. Therefore, temporary workers should be more likely to suffer job losses due to a slowdown in firms’ production.

The substantial role of fixed-term contracts in many industrial and service branches and the widespread use of external numerical flexibility during the 1960s suggest that temporary employment was a prominent managerial strategy that could not be solely related to the instability of Spanish firms’ production. In a similar vein, social planners in 1963 remarked that temporary employment not only affected occupations associated with seasonality or having an unstable demand. Instead, there were sociological factors that also shaped the use of temporary employment (CPDES, 1963: 221): “Although in some cases temporary employment is the result of provisional or circumstantial situations, as jobs of short duration or periods of trial, in others is the consequence of a determined way to understand labor relations among employers, typical of a scarcely developed social mentality.”

Table 7 examines this issue in more detail by looking specifically at the main occupational categories reported in the 1970 census. This table focuses mainly on those occupations that are usually presented as secure or skilled. The results show that the use of fixed-term contracts as a source of flexibility was significant in many of these occupations.

A notable case can be found among professional and technical occupations where the average incidence of these contracts reached 10.9 percent. Despite very low unemployment in urban labor markets and a severe shortage of skilled labor, more than 10 percent of teachersFootnote 10 and physiciansFootnote 11 had fixed-term contracts, and these were also significantly present in very skilled occupations such as lawyers and engineers. Temporary employment seems to have been similarly prevalent in occupations such as mail carriers, store clerks, or insurance and estate agents. Among blue-collar workers, a significant share of temporary contracts among drivers and assembly workers can be found. Other blue-collar occupations but with a stronger relation to the construction sector also registered high rates of temporary employment: painters (20.9 percent), plumbers, locksmiths, and sheet metal workers (12.4 percent), and jewelers (11.9 percent).

The decline of temporary employment during the 1970s

Previous research had hypothesized that the combination of growing labor protest and jurisprudence that progressively favored stable forms of employment relations led to a decline in the role of fixed-term contracts. Prior to this article, Toharia had shown that temporary employment in the construction and food industries in firms with more than 10 employees had fallen steadily from 30–40 percent to 15 percent between the early 1960s and 1975 (Fina, Meixide and Toharia, Reference Fina, Meixide, Toharia and Rosenberg1989: 120; Toharia, Reference Toharia2002). As we have seen, temporary employment was not limited to these volatile sectors and was very high in the 1960s. However, between 1970 and 1975, the available information presented in Tables 4 and 8 suggests that the evolution of temporary employment followed the pattern proposed by this author. Nevertheless, it shows that temporary employment remained important in many sectors of the economy, but less so than in previous decades, while it began to play a very limited role in management strategies in large-scale industry, public administration, and the financial sector, where public employment played a major role.

Table 8. Fixed-term employment between 1970 and 1975 in Spain

Source: 1970 Spanish Population Census and 1975 Spanish Municipality Registers.

a If we include seasonal employment after including the salaried employment differential between the census and annual salaried employment reported by Fundación BBV (Reference Fundación1999). Toharia also suggested similar percentages See Fina, Meixide, and Toharia (Reference Fina, Meixide, Toharia and Rosenberg1989).

However, the percentage difference present in these data needs to be taken with caution and requires an in-depth analysis of the potential explanatory variables. Although future research will need to corroborate and explain the factors that may have restricted fixed-term contracts during this period, following Toharia (Reference Toharia2002) three potential factors could suggest a significant decline in temporary contracts, especially between 1973 and January 1976. First, as a result of the 1973 crisis, most branches registered significant job losses which could have affected the rate of temporary employment (Table A.3. in Supplementary Materials). Second, while the Spanish legislation was less restrictive regarding the cases in which temporary employment could be used than in other European countries (see Section 5.1), legislation and jurisprudence had gradually constrained its use delimiting fixed-term contracts to exceptional or seasonal needs for labor (Toharia, Reference Toharia2002).

Third, in combination with the prior two factors, compared with 1966–1969, the average number of strikes, participants, and working days lost between 1973 and 1976 sharply increased, as well as expanding sectorally and regionally. Although the number of participants and days of work lost were substantially lower than in the period 1976–1979, this implied a growing capacity to bargain in comparison to the previous period (Table A.4). Whereas in the 1960s, industrial disputes had been concentrated in the metallurgical sector and a few specific regions, such as Asturias, Vizcaya, Barcelona, and Madrid, they gradually spread to other sectors and regions. In addition, clandestine and pro-democracy unions scored a major victory in 1975 by winning the majority of union delegate posts in elections to the Francoist union, the Organización Sindical, through the strategy of infiltration (Molinero and Ysàs, Reference Molinero and Ysàs1998; Cárdenas, Reference Cárdenas2023). In this regard, in Asturias, a region with a high share of metallurgy and mining, some authors have shown that between 1971 and 1975 a growing number of workers’ demands in the courts corresponded to legal claims aimed at converting fixed-term contracts into permanent ones (Benito, Reference Benito1993:394).

Other sources of external numerical flexibility

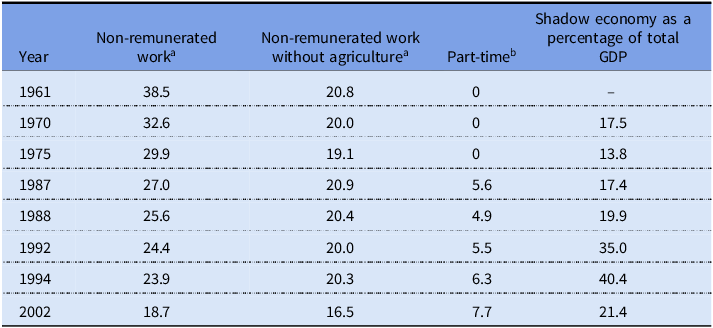

Workers on fixed-term contracts were a substantial share of the total working population. However, these practices would be even more widespread if we consider other typologies of flexible arrangements that could play a significant role in managerial strategies and be inherited by the democratic regime. Firms also implemented external numerical flexibility by the use of three main flexible sources of labor: outsourcing, non-remunerated work, and the shadow economy.

First, during the 1960s and early 1970s, self-employment and family work comprised 20 percent of total employment in the nonagricultural sector. This proportion remained stable after the end of the dictatorial regime until the end of the 20th century (Table 9). Indeed, self-employment and family work were additional sources of flexibility embedded in the management strategies. In 1973, these forms of work were particularly important in the services sector, where they accounted for 26 percent of employment, compared with only 11 percent in industry. Notable cases in the service sector were education and health services, retail, ship repair, and tourism, where self-employment and family work accounted for 35–45 percent of total employment. In industry, sectors such as textiles and footwear, food, beverages and tobacco, and wood and wood products accounted for 17–20 percent (BBV, Reference Fundación1999).

Table 9. Other forms of non-regular employment in Spain, 1961–2002

Source: Fundación BBV (Reference Fundación1999); 1987–2019 Economically Active Population Survey; Pickhardt and Sardà (Reference Pickhardt and Jordi2015).

a Non-remunerated work comprises self-employment and family work.

b Part-time contracts did not exist during the Francoist dictatorship.

Specifically, non-salaried family work was a significant mechanism of external numerical flexibility in some branches, especially in retail, the food industry, the wood industry, and hospitality and restaurants. The most remarkable case is the retail sector: this type of workforce comprised 10.4 percent and 8.5 percent of total employment in 1970 and 1975, respectively, according to the 1970 Census and 1975 Municipality registers.

Second, the use of outsourcing as an auxiliary and temporary workforce was a common feature in many industries as a mechanism of labor flexibilization, the so-called “contratas.” To provide this service, firms and self-employers frequently hire temporary workers by using fixed-term contracts. This management strategy was particularly prominent in industry and construction. Thus, for example, an internal survey by The Union of Wood and Products of Wood and Cork of the Francoist sole trade union estimated that 29.3 percent of self-employed workers had hired temporary workers in 1968 (Sindicato Nacional de Madera y Corcho, 1969). The use of outsourcing by temporarily subcontracting workers is also documented as a significant share of the total workforce in the shipbuilding industry in Coruña (Allén, Reference Gómez-Allén and Ruiz1993), Asturias (Benito, Reference Benito1993), Cádiz (Gutiérrez and Roca, Reference Florido del Corral, Gutiérrez-Molina and Roca2009), Valencia (Saz, Reference Saz2004), and Biscay (Pérez-Pérez, Reference Pérez-Pérez2002). In Cádiz, oral testimonies suggest that 50 percent of the total workforce was subcontracted in the mid-1970s (Gutiérrez and Roca, Reference Florido del Corral, Gutiérrez-Molina and Roca2009: 35).

In 1970, the significant role of these practices in the Spanish labor market motivated the adoption by the Ministry of Labor of new legislation (Executive Order of 17 December 1970) aimed at “preventing and sanctioning fraudulent activities in the recruitment and employment of workers.” In the words of contemporary labor law experts, this new regulation represented “one of the most important labor regulations of recent years” (Rodríguez-Piñero, Reference Rodríguez-Piñero1972:5). This regulation prohibited and imposed fines for the use of outsourcing as a mechanism to use temporary workers for tasks related to the main activity of the company or for ancillary activities that constituted a permanent demand of the company. In both cases, the law required the company to hire the worker and include him or her in the company’s permanent staff. As a result, this legislation became crucial in many industrial disputes that took place between 1970 and 1975, particularly in the metallurgy sector, with special significance in the shipbuilding industry, and construction (Benito, Reference Benito1993: Allén, Reference Gómez-Allén and Ruiz1993).

Finally, employing workers in the shadow economy was another common managerial strategy during the period. According to Pickhardt and Sardà (Reference Pickhardt and Jordi2015), the shadow economy reached 17 percent of GDP in 1970. In this regard, these authors highlight that labor market dynamics were the main driving force of the shadow economy in Spain. This is consistent with qualitative research that has noted that in branches such as domestic service, hospitality and retail, and industrial activities like the clothing industry and small assembled goods – for example, toys – the shadow economy played a key role intimately associated with female work (Banyuls and Recio, Reference Banyuls, Recio, Damian, Colette, Gail and Távora2017).

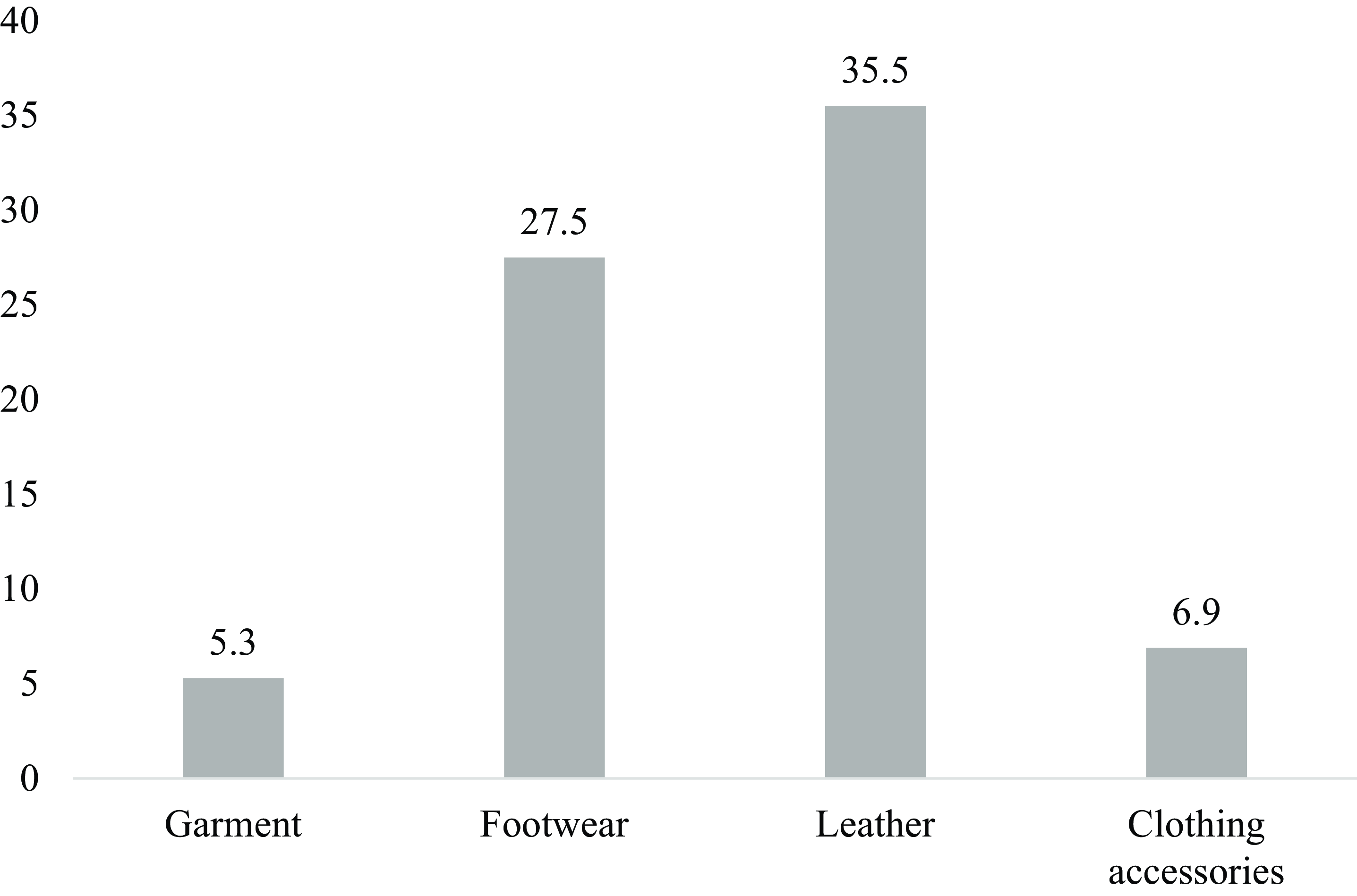

Home work was the most remarkable case of external numerical flexibility associated with the underground economy with a particular incidence of women’s work. Some contemporary reports stated that in 1970, 12 percent of women in Spain worked at home in productive activities (FOESSA, Reference Fundación1970: 1062). This managerial strategy was widespread in sectors such as the textile, footwear, jewelry, and toy industry. These practices that usually involved piece-rate payment became an essential part of the structure in these subbranches. For example, between 1965 and 1972, home work accounted for 5.3 percent of total wages paid in the garment industry, 27.5 percent in the footwear industry, and 35.5 percent in the leather industry (Figure 3). Since this work was seasonal and often was paid in piece rates, the number of workers involved could have been much higher, even in the case of the garment industry, where economies of scale reduced the weight of home work in firms’ total payments from 10 percent in 1965 to 5 percent in 1972.

Figure 3. Share of home work piece rates in total wage payments by subbranch in the textile and footwear industry in Spain, 1965–1972 (average).

Source: INE (1965–1972).

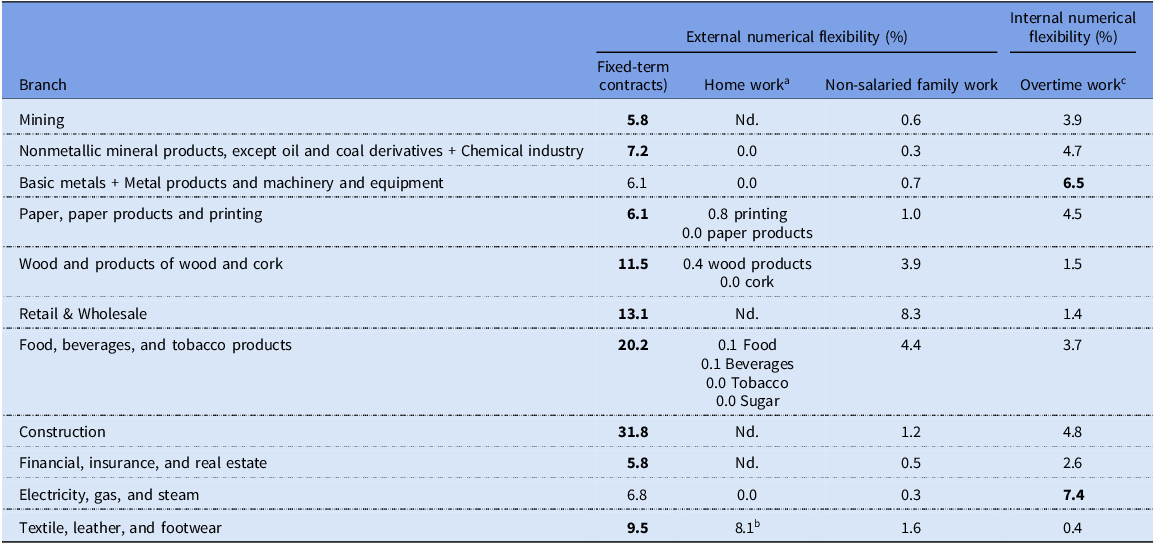

External numerical flexibility within managerial practices

External numerical flexibility, in its various forms, played an important role in the management practices of Spanish firms during this period. They were part of a set of potential flexibility mechanisms used by firms. The aforementioned literature has seen internal numerical flexibility as the main management strategy of firms during the period. The use of overtime would have been a mechanism to cope with the high costs of dismissal and the rigidity of the Franco labor market. However, as Table 10 shows, both external numerical flexibility and internal numerical flexibility (overtime work) were complementary parts of the management strategies implemented by firms, of varying frequency depending on the branch.

Table 10. Levels of labor market flexibility: external vs internal by branch. Spain, 1970

Source: 1970 Spanish Population; Serrano and Malo de Molina (Reference Serrano and Malo1979: 148); INE (1965–1972).

Note: Official data on overtime do not include branches such as hospitality and restaurants, health care, education, transport, domestic work, and other services. However, data presented here show that external numerical flexibility in the private sector exceeded 10 percent and in most cases reached 20 percent in these branches.

a Average total payments in exchange for home work in 1970.

b Textile, leather, and footwear includes both the production of cloth and its transformation into consumer goods (this category is displayed in Figure 3).

c Overtime as a percentage of the total working hours.

We can distinguish four categories depending on the prevalence of each management strategy. First, branches in which the use of overtime work is the main mechanism of flexibility, or at similar levels to temporary employment, usually between 5 and 10 percent of the total workforce. These are economic activities associated with economies of scale and stable levels of monthly production, a significant role of public ownership or reliance on skilled labor, such as electricity, finance and banking, administrative work, paper, basic metals, mining, or machinery and equipment.

Second, industries in which fixed-term contracts were the main management strategy, although internal numerical flexibility could be a complementary mechanism. These are branches in which the prevalence of temporary employment reached 10–15 percent of the total workforce, such as transport, education, health, wood products, and other services. Third, economic activities with a high degree of seasonality or unstable labor demand, where reliance on overtime was important, but temporary employment was crucial, accounting for between 20 and 50 percent of the total workforce. These are construction, domestic work, agriculture, tourism, and the food industry. Finally, a fourth group of sectors comprised activities in which the use of overtime played a minor role and external numerical flexibility as the main mechanism of flexibilization took various forms. These are enterprises that have structured their operations with a particular reliance on other sources of numerical flexibility, such as family work, especially in retail, and home work, as in the textile, leather, and footwear industries.

Temporary employment in Spain in the international context

The regulation of temporary work from an international perspective

The persistence of external numerical flexibility during the Franco dictatorship took place in a particular and anomalous institutional context compared to its democratic neighbors. As a result of the Spanish Civil War and the imposition of the dictatorial regime, the Spanish labor market was characterized by a very high imbalance of power in favor of employers. While in most Western European countries, these decades witnessed the consolidation and institutionalization of strong labor movements, Spanish trade unions were persecuted and trade union and political freedoms were suppressed.

Within this political scenario, employers had discretionary power within their firms. Moreover, not only did Spanish employers have greater bargaining power and control over their employees than most of their Western counterparts, but they also had a greater capacity to circumvent labor regulations. For example, noncompliance with labor regulations on issues such as the number of hours of overtime required by law was characteristic. In addition, Franco’s labor institutions, the vertical union, the labor courts, and the labor inspectorate, failed to protect workers and adequately monitor working conditions – although the courts, in interaction with the growing labor movement, tended to be more responsive to workers’ demands from the 1960s onwards (Molinero and Ysás, Reference Molinero and Ysàs1998; Vilar, Reference Vilar2013; Sola, Reference Sola2014; Cárdenas, Reference Cárdenas2023). A paradigm of this is the inspection service, which was deliberately set up by the regime as barely operational and with little protective capacity, due to the lack of personnel and funding, de-professionalization, and laxity in the imposition of fines (Sánchez-Mosquera, Reference Sánchez-Mosquera2024). Consequently, Spanish companies could rely more on temporary and informal labor markets to reduce costs due to their greater bargaining power and capacity to circumvent regulations.

Aside from these key differences in labor market functioning, one of the main comparative characteristics of the Spanish labor legislation was the high cost of dismissal of employees on permanent contracts in line with their democratic neighbors but also the employer’s capacity to dismiss at will. As part of the process of economic restructuring carried out under the 1959 Stabilization Plan, the Spanish regime relaxed the laws on the dismissal of permanent workers to facilitate firms’ adjustment to economic liberalization. According to Malo (Reference Malo2005), the legislation provided an incentive for employers’ use of disciplinary dismissals, as the law provided for free dismissal in exchange for costly compensation (one year’s salary if the dismissal was declared unjustified, four years’ salary if companies had more than 50 workers on permanent contracts). This constituted a significant difference compared to France, West Germany, and Italy since in these countries, all dismissals were subject to review by labor courts and social agents. As Emmenegger (Reference Emmenegger and Oude2021) notes, the German case is particularly relevant because the Labor Code urged employers to consider alternatives before dismissal, such as management reorganization, to avoid job losses. Thus, although the costs of dismissals were similar to other European countries – only more expensive for companies over 50 workers than Italy and West Germany – what made permanent employment more flexible in Spain was the capacity to dismiss unconditionally (Table A.5. in Supplementary Materials).

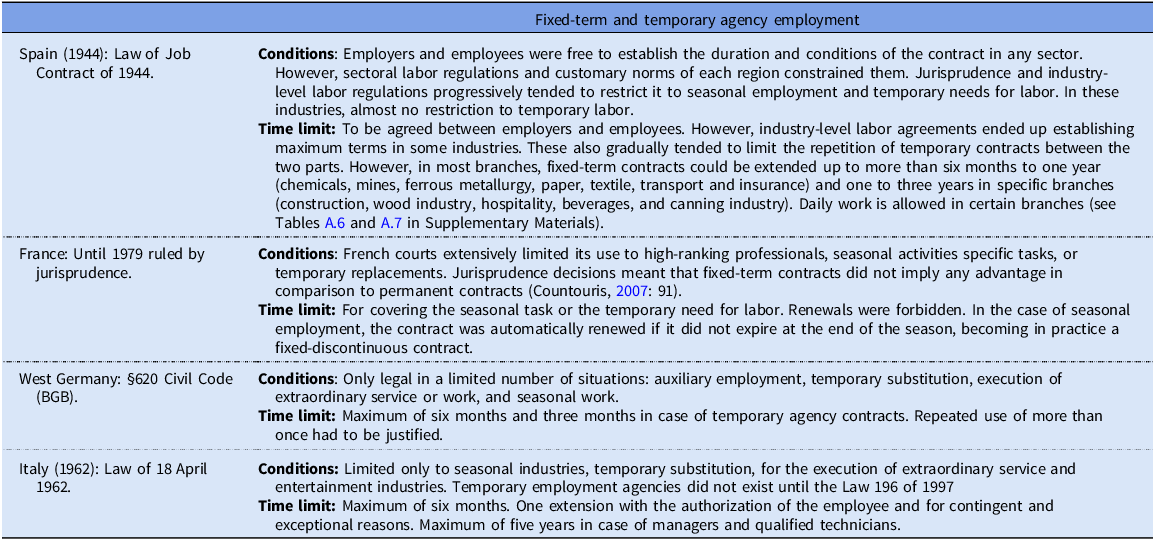

Nonetheless, labor regulations under Franco’s regime diverged to a greater extent from those of these countries in the regulation of fixed-term contracts. The Spanish Law of Job Contract of 1944 established an extremely liberal understanding of short-term contractual relationships between employers and employees. Both parties were free to agree on the duration and conditions of work. This extremely liberal understanding of labor relations was gradually constrained by industry-level labor legislation, labor courts, and the strength of the labor movement, which limited its relevance, particularly in those situations where there was flagrant use of fixed-term contracts (Toharia, Reference Toharia2002).

However, despite this progressive restriction, the legislation provided greater incentives for the use of fixed-term contracts, including daily, temporary, and seasonal work. At the end of Franco’s dictatorship, employers had more scope to use fixed-term contracts and other sources of flexibility than in West Germany, France, and Italy (Table 11 and Tables A.6 and A.7 in Supplementary Materials).Footnote 13

Table 11. Characteristics of temporary contracts in European countries in 1973

Fixed-term and agency temporary work

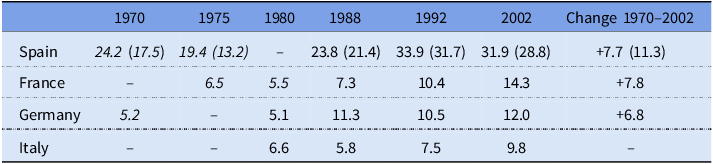

In the same vein, the incidence of fixed-term contracts in the Spanish labor market is more remarkable when compared with other contemporary Western countries. Table 12 shows the results of various estimates of the share of fixed-term contracts and temporary work in the compared countries up to the early 1970s and official data from the early 1980s. In France and West Germany, agency temporary work had developed in the early 1960s implying a significant growth of temporary work in these countries, especially significant in branches such as services in France and construction and metal industries in the case of West Germany (Coriat, Reference Coriat1982; Emmenegger, Reference Emmenegger and Oude2021). Therefore, I use the official data on temporary agency work in 1973 and the relative proportion of total temporary employment in the early 1980s, to estimate total temporary employment in 1973 (see Table A.8 in Supplementary Materials).

Table 12. Share of temporary employment (fixed-term + temporary agency work) in Western countries, 1970–2019

Source : Spain: 1970 Spanish population census; 1975 municipality registers; 1985–2002 Economically Active Population Survey. France: 1970 corresponds to 1975. Data from Bernard Fourcade (Reference Fourcade1992) and 1980–2002 Enquêtes emploi INSEE. Germany: 1970 corresponds to 1973, data from Statistisches Bundesamt, Fachserie 1, Reihe 4.1.1, various volumes, Bundesanstalt fur Arbeit, various volumes; 1980 corresponds to 1984 data from OECD Labour Market Statistics. Italy: 1980 corresponds to 1983. Data from 1983–2002 Rivelazione delle forze di lavoro.

Note: In parenthesis, excluding agricultural employment. Estimations in italics. For a detailed description of the procedure conducted to calculate the estimations see Table A.8 in Supplementary Materials.

Although these estimates could be subject to certain biases, the results clearly show that the gap between Spain and these countries already existed. Specifically, the incidence of temporary contracts was almost 20 percent higher in Spain than in France and Germany. Similarly, the percentage growth of this indicator in Spain between 1970 and 2002 is similar to that of the European countries mentioned, and only about 5 points higher if Spanish agriculture is excluded. Thus, in terms of the prevalence of temporary employment, the Spanish labor market already significantly diverged from the European trajectory two decades before the impact of the labor reforms of the mid-1980s.

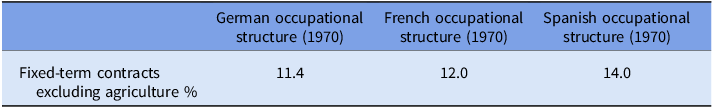

The higher prevalence of fixed-term contracts in Spain cannot be attributed to compositional effects related to the greater role of unstable or seasonal activities in the Spanish economy as Polavieja also noted for the period 1984 and 2004 (Polavieja, Reference Polavieja2006). The percentual differences between the proportion of nonagricultural employment of the most representative unstable sectors in Spain compared to France and West Germany comprised less than 4 percent (see Table A.9 in Supplementary Materials). In Table 13, I weigh the Spanish occupational structure according to the share of employment in each branch in West Germany and France. As can be seen, the result of this exercise does not imply a significant modification of the rate of fixed-term contracts in Spain.

Table 13. Fixed-term nonagricultural employment in Spain in 1970 weighted according to the occupational structure of West Germany and France

Source : Spain: 1970 Spanish Population Census and Fundación BBV (Reference Fundación1999). Germany: Statistiches Bunesamt Volkszahlug. France: INSEE. Annuaire statistique de la France.

Note: As the 1970 Spanish Census was collected in December, it does not include most of the seasonal employment in the tourism sector and other seasonal branches that increase their labor demand during the rest of the year. For example, those workers from hotels and restaurants that only opened seasonally, particularly during the summer season or the Holy Week are not included.

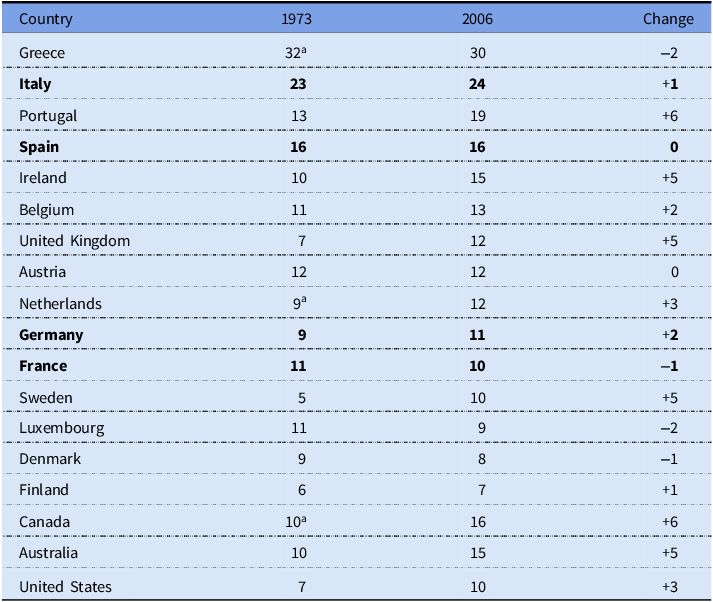

Other forms of labor flexibility

The role of other forms of labor flexibility also differed, although they had significant similarities with the rest of the Mediterranean countries. This is particularly the case for the impact of self-employment and the underground economy. Self-employment in Spain had one of the highest shares of all OECD countries at the time. Only countries in which this type of employment has historically played a key role in the functioning of their labor markets, such as Greece and Italy, had higher shares (Table 14).

Table 14. Share of Self-Employment in nonagricultural sectors, Selected OECD Countries, 1973 and 2006

Source: Vosko (Reference Vosko2010: 171).

a Corresponds to 1979.

Similarly, the shadow economy, with the labor market as an important driving force, represented a larger share of the economy in the 1960s and early 1970s than in other European countries. According to the literature on the subject (Dell’Anno, Gómez-Antonio and Pardo, Reference Dell’Anno, Gómez-Antonio and Pardo2007), this pattern could be analogous to the rest of Mediterranean countries, particularly Italy, Portugal, and Greece, where underground work, particularly associated with women’s work and home work, was a widespread feature of the Fordist period (Betti, Reference Betti2020).

Conclusions

This study revisits labor flexibility during Franco’s dictatorship and its long-term impact. It suggests that external numerical flexibility played a significant role in the Francoist labor market: between the 1960s and the early 1970s, fixed-term contracts reached 24–30 percent of total employment. More importantly, the analysis shows that these management practices were widespread at different levels in nonagricultural sectors, ranging between 14 and 17 percent of the workforce. Besides, Franco’s labor market shared the characteristics of low-tier labor markets described since the mid-1980s: age and gender segmentation and shared use of external numerical flexibility across sectors. In this regard, firms understood women’s work as a more flexible workforce taking advantage of the sociocultural background within a breadwinner society.

This is in line with Banyuls and Recio’s hypothesis (Reference Banyuls, Recio, Damian, Colette, Gail and Távora2017) on the significant role of external numerical flexibility in the management practices among some unstable branches of the Spanish economy during Franco’s dictatorship that could have been inherited by the labor market after the return of democracy. However, the analysis suggests that fixed-term contracts did not only involve employment in unstable or seasonal employment sectors. Although at a comparatively lower level, employers in many services and industrial sectors not similarly affected by these variations used temporary workers at significant levels. Besides, these branches also relied on other sources of temporary employment. Self-employment, outsourcing, family work, and the underground economy, particularly related to home work, were crucial parts of firms’ management strategies. These forms of numerical flexibility were complementary to overtime work having a higher incidence depending on the historical and structural characteristics of each branch. Still, excepting large-scale industries, often with a considerable percentage of state-owned companies, or some skilled occupations, temporary employment was the primary mechanism of labor flexibilization.

Flexible employment took place in an institutional context that was not as protective as other legal corpora and jurisprudence from other European countries. Similarly, in the early 1970s, the Spanish labor market registered a dramatically higher prevalence of temporary employment than other comparable European labor markets, even considering the differential occupational structure. Therefore, Spain was already an anomaly almost two decades before it was generally assumed to be.

These findings may reframe the legacy of Franco’s labor market. The persistence of the high incidence of temporary employment during the Dictatorship implies that the extensive use of external numerical flexibility was at the core of most firms’ structure for decades. This indicates a significant divergence from the situation in northern European societies. Therefore, this different pattern of labor market functioning from 1939 to 1975 could be an additional factor in understanding why Spain has registered higher levels of temporary employment since the late 1980s.

Finally, this study contributes to a growing body of literature that emphasizes the noteworthy incidence of temporary employment in the Western world during the 30 years following the Second World War. In this regard, comparative studies on the prevalence of temporary employment with other southern Mediterranean countries such as Portugal and Greece could provide valuable insights. Particularly, exploring the potential influence of the prolonged dictatorships in these countries on shaping future developments could be very useful as well.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ssh.2025.3

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the participants of the conference “Flex or tenure? Comparative development of flexible work, 1950s–present” at the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam for their observations and suggestions. I am also grateful for the comments of Montserrat Llonch, Albert Recio, and Ramon Molina in the early stages of this research. Finally, the external referees and the editors, Kris Inwood and Rebecca Jean Emigh, provided very helpful feedback.