Three challenges: ageing, obesity, climate

In 2019, the Lancet Commission described the global syndemic of obesity, undernutrition and climate change – three interconnected challenges that threaten both human and planetary health(Reference Swinburn, Kraak and Allender1). While this review does not aim to address the full scope of the syndemic, it does centre on one critical intersection: older populations living with overweight and obesity in the context of sustainable nutrition.

Worldwide, the prevalence of obesity continues to rise, not only among younger individuals but also among older adults(2). Simultaneously, life expectancy is increasing in many regions, contributing to a growing older population(3). The increase in life expectancy comes with new public health challenges. One of these is sarcopenic obesity, a condition characterised by the coexistence of excess adiposity (obesity) and low muscle mass and muscle function (sarcopenia)(Reference Donini, Busetto and Bischoff4). Older adults with obesity are particularly vulnerable to developing sarcopenic obesity, especially in the absence of sufficient physical activity and protein intake. Sarcopenic obesity is associated with severe negative health outcomes including mortality, decreased quality of life and higher dependence(Reference Prado, Batsis and Donini5,Reference Rubino, Cummings and Eckel6) .

Preserving muscle mass and strength should therefore be an important goal in healthy ageing, also in those with obesity(Reference Schoufour, Tieland and Barazzoni7). Adequate protein intake, alongside regular physical activity, especially resistance exercise, is essential to prevent or treat sarcopenia and sarcopenic obesity. However, given the urgent need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and environmental footprints, greater attention should be directed towards the source of dietary protein. This calls for a transition from predominantly animal-based to more plant-based dietary protein sources, which are generally associated with lower environmental footprints(Reference Willett, Rockström and Loken8,Reference Tilman and Clark9) . This review aims to summarise current insights on environmentally sustainable nutrition strategies for older adults with obesity. It highlights the need to align protein recommendations with environmental sustainability goals, taking into account both healthy ageing and the environment.

Preventing sarcopenia in individuals with obesity: a priority for healthy ageing

Obesity and sarcopenia, particularly sarcopenic obesity, are often overlooked until the onset or exacerbation of other diseases necessitates secondary care. This oversight is concerning, as these conditions are significant contributors to various chronic diseases, including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, osteoarthritis and falls and physical disability, all increasing healthcare utilisation and costs(Reference Prado, Batsis and Donini5,Reference Rubino, Cummings and Eckel6) . This is particularly important for the older population, and assessment and monitoring should start at least in midlife to enable timely prevention and intervention. Recent advancements have enhanced the definition and diagnostic criteria for obesity, sarcopenia and sarcopenic obesity, providing a foundation for more effective identification and management strategies(Reference Donini, Busetto and Bischoff4,Reference Rubino, Cummings and Eckel6,Reference Cruz-Jentoft, Bahat and Bauer10) . In European older adults, the prevalence of overweight and obesity is estimated to be as high as 60%, while sarcopenia affects approximately 10–27% and sarcopenic obesity 1–23%, depending on the population and applied definitions(Reference Prado, Batsis and Donini5,Reference Benz, Pinel and Guillet11–Reference Gortan Cappellari, Guillet and Poggiogalle13) . A recent cohort study has shown that the hazards of sarcopenic obesity include a threefold increase in the risk of premature mortality, driven by significant alterations in fat mass, muscle mass and muscle strength(Reference Benz, Pinel and Guillet11) based on the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and the European Association for the Study of Obesity consensus criteria(Reference Donini, Busetto and Bischoff4). It is critical to emphasise that all older adults are at risk of gaining fat mass while losing muscle mass, leading to obesity, sarcopenia or sarcopenic obesity. Muscle mass and function reach their peak at the end of the third decade of life and subsequently decline at a rate of approximately 0.4% per year(Reference Schoufour, Tieland and Barazzoni7). One of the underlying mechanisms is anabolic resistance, which increases with age and is further exacerbated in older adults with obesity(Reference Smeuninx, McKendry and Wilson14,Reference Traylor, Gorissen and Phillips15) . Moreover, obesity and sarcopenia share aetiologies such as poor nutrition and physical inactivity, which exacerbate their interplay, creating synergistic and detrimental cycles that place a greater burden on older adults. The consequences of obesity, sarcopenia and sarcopenic obesity are severe and highlight the urgent need for preventive and therapeutic interventions(Reference Prado, Batsis and Donini5,Reference Benz, Pinel and Guillet11,Reference Gortan Cappellari, Guillet and Poggiogalle13) .

The essential role of diet and physical activity

Preventing sarcopenic obesity involves not only avoiding weight gain and reducing excess fat mass but also ensuring the preservation of muscle mass and muscle function(Reference Schoufour, Tieland and Barazzoni7). This requires a combined strategy of reducing total energy intake while ensuring sufficient protein intake, both in terms of quantity, quality and distribution, integrated with regular moderate to vigorous physical activity and particularly resistance exercise(Reference Eglseer, Traxler and Schoufour16,Reference Eglseer, Traxler and Embacher17) . The current recommended daily allowance for protein is 0.83 g/kg/d(18–Reference Rand, Pellett and Young20). However, several experts recommend increasing protein intake to at least 1.2 g/kg/d, with approximately 25–30 g of protein per meal for older adults(Reference Deutz, Bauer and Barazzoni21,Reference Bauer, Biolo and Cederholm22) . An energy-restricted diet without sufficient protein and not supported by appropriate physical activity, especially resistance exercise, can lead to significant muscle mass loss and impaired muscle function(Reference Trouwborst, Verreijen and Memelink23). Protein plays a crucial role in muscle maintenance and growth, and insufficient intake, especially during periods of weight loss, can accelerate muscle mass loss. In individuals with overweight or obesity, weight reduction often results in concurrent loss of muscle mass, increasing the risk of functional decline and other health complications(Reference Ashtary-Larky, Bagheri and Abbasnezhad24). Depending on treatment approaches and individual differences, multiple randomised controlled trials have shown that fat-free mass loss represents 17–35% of total weight loss(Reference Martins, Gower and Hunter25–Reference Turicchi, O’Driscoll and Finlayson27). Likewise, focusing solely on physical activity without adjusting dietary intake may not lead to meaningful fat loss or preservation of muscle mass(Reference Eglseer, Traxler and Embacher17). This is partly because individuals may overcompensate for physical activity by reducing other daily activities and/or increasing their energy intake(Reference Melanson, Keadle and Donnelly28), which diminishes the effectiveness of exercise-induced weight loss. Effectively preventing and treating obesity, sarcopenia and sarcopenic obesity therefore requires physical activity including resistance exercise combined with adequate protein and energy intake.

Role of protein in prevention and treatment of sarcopenic obesity

In clinical practice, the treatment of obesity should be accompanied by strategies to prevent muscle mass loss. Dietary protein is an essential factor associated with the development of sarcopenic obesity(Reference Pinel, Guillet and Capel29). Protein plays an important role in both nutritional and exercise-based interventions aimed at the prevention and management of (sarcopenic) obesity(Reference Eglseer, Traxler and Schoufour16,Reference Eglseer, Traxler and Embacher17,Reference Reiter, Bauer and Traxler30) . However, the knowledge regarding optimal protein requirements in individuals with obesity remains limited(Reference Weijs31). Although the effectiveness of protein in mitigating sarcopenia is supported by evidence, its implementation is not without challenges, including those related to cultural acceptability and dietary preferences(Reference Biersteker, van den Helder and van der Spek32). Nutrition and exercise intervention trials have shown that during weight loss in older adults with obesity, muscle mass can be preserved when sufficient protein intake is combined with resistance exercise(Reference Verreijen, Engberink and Memelink33–Reference Memelink, Pasman and Bongers35). Furthermore, a digitally supported home-based exercise intervention was able to maintain muscle mass in older adults with or without overweight, but only when protein intake was adequate(Reference van den Helder, Mehra and van Dronkelaar36). When evaluating protein intake in older adults with or without obesity, studies have shown that individuals with a higher protein intake tend to consume more animal-based protein, while intake of plant-based protein remains relatively constant(Reference Koopmans, Van Oppenraaij and Heijmans37,Reference van den Helder, Verlaan and Tieland38) .

Globally, food production poses significant environmental risks, with animal-based foods contributing disproportionately to greenhouse gas emissions and other ecological impacts(Reference Willett, Rockström and Loken8,Reference Tilman and Clark9) . Partly replacing animal-based foods with plant-based alternatives, such as legumes, nuts and vegetables, can help reduce the environmental footprint. In addition, a more plant-based diet has been associated with a lower risk of overweight, obesity and non-communicable diseases, including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes and cancer(Reference Key, Papier and Tong39). This can be attributed to their lower energy density and lower intake of saturated fatty acids, as well as higher fibre content compared with omnivorous diets(Reference Bakaloudi, Halloran and Rippin40,Reference Sobiecki, Appleby and Bradbury41) . Therefore, policy makers and health councils recommend to consume at least 60% plant-based protein to achieve the future climate goals(Reference Willett, Rockström and Loken8,42–44) . However, the transition towards diets with more than 60% plant-based protein might affect the intake of both protein quantity and quality and thereby the stimulation of muscle protein synthesis and maintenance of muscle mass, strength and function(Reference Willett, Rockström and Loken8,45–Reference Gorissen, Crombag and Senden47) .

Plant-based protein sources: implications for muscle protein synthesis and muscle health

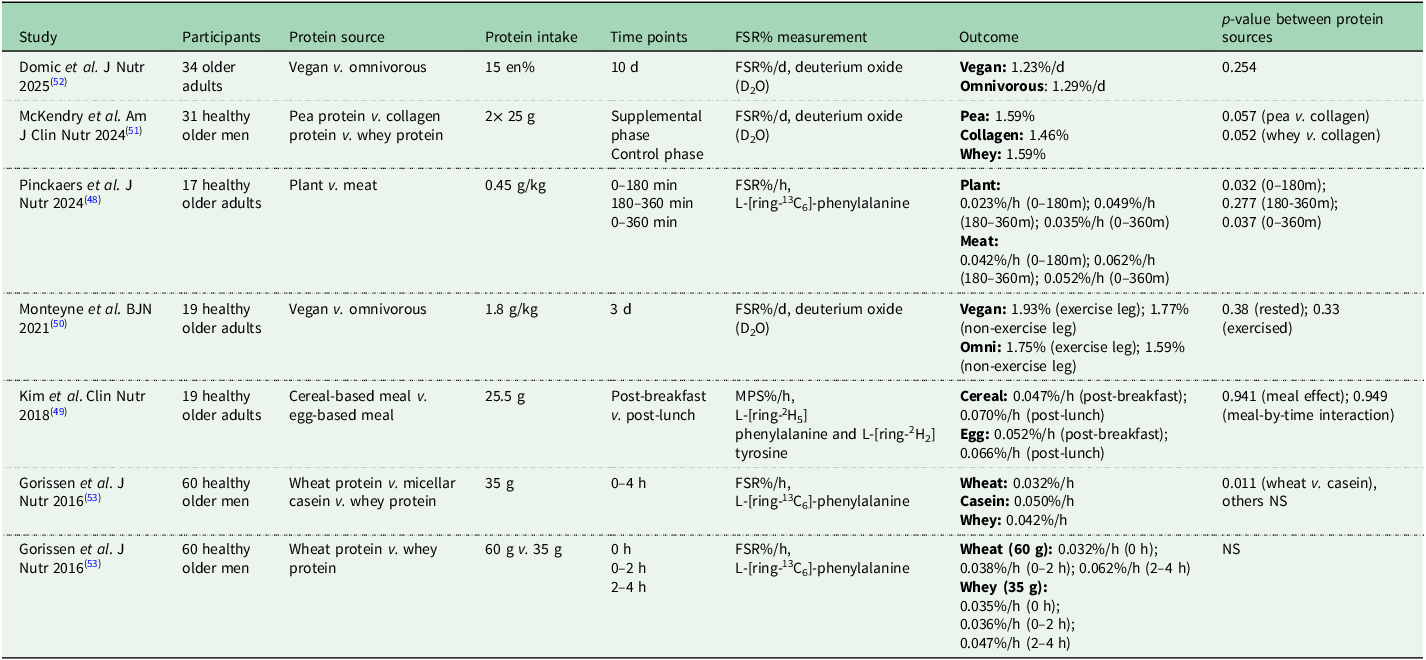

Muscle protein synthesis assessments, although conducted in just a couple of hours, not easily available and expensive, offer a way to compare animal-based and plant-based protein sources. Several studies have investigated the effect of different plant-based compared to animal-based protein sources on postprandial muscle protein synthesis in older adults (Table 1). These studies have demonstrated that both the source as well as the dose of dietary protein can significantly influence muscle protein synthesis rates in older adults. Animal-based protein can induce higher anabolic responses than plant-based protein in this population, as shown by higher postprandial muscle protein synthesis rates(Reference Pinckaers, Domić and Petrick48) and greater whole-body protein net balance(Reference Kim, Shin and Schutzler49). However, other studies have shown that high doses of alternative protein sources, such as mycoprotein(Reference Monteyne, Dunlop and Machin50), isolated plant protein like pea protein(Reference McKendry, Lowisz and Nanthakumar51), or a well-balanced vegan diet(Reference Domić, Pinckaers and Grootswagers52), can support muscle protein synthesis rates comparable to those of animal-based protein and/or diets. In contrast, plant-based protein with lower digestibility or suboptimal amino acid profiles, such as wheat, have shown to elicit weaker anabolic responses in older adults and therefore must be consumed in larger quantities to effectively stimulate muscle protein synthesis(Reference Gorissen, Horstman and Franssen53). Yet, combining different plant-based sources could lead to a more complete amino acid profile by complementing each other(Reference Pinckaers, Trommelen and Snijders54). For example, combining rice, which is low in lysine and high in methionine, with peas, which are low in methionine and high in lysine, results in a more complete amino acid profile.

Table 1. Postprandial muscle protein synthesis in response to animal-based v. plant-based protein sources in older adults

FSR = fractional synthetic rate, MPS = muscle protein synthesis, NS = not significant (no p-value mentioned).

Two systematic reviews and meta-analyses have compared the effects of animal v. plant protein on muscle outcomes(Reference Reid-Mccann, Brennan and Ward55,Reference Lim, Pan and Toh56) . Both found a modest advantage of animal protein compared to plant-based protein other than soy on muscle mass, irrespective of receiving resistance exercise. Additionally, older adults have shown a modest improvement in lower body strength, with no effect on upper body strength or physical performance(Reference Reid-Mccann, Brennan and Ward55). In adults with obesity, energy restriction without an exercise programme led to weight loss, of which approximately one-third muscle mass loss(Reference Hill, Harris Jackson and Roussell57–Reference Beavers, Gordon and Easter61). No differences were observed between animal-based and plant-based protein sources or diets, whether supplemented or not, in terms of changes in body mass or muscle mass. However, apart from protein quality, it is important to note that the effects of animal-based v. plant-based protein may be comparable when consumed in similar quantities. At the same time, ensuring sufficient protein intake can be more difficult with predominantly plant-based diets because plant-based foods generally have a lower protein density and therefore provide less protein per typical portion size(Reference Sobiecki, Appleby and Bradbury41,Reference Pinckaers, Trommelen and Snijders54) .

In summary, these findings underscore the importance of considering both the quantity and quality of protein when aiming to optimise muscle maintenance in older adults.

Encourage older adults to shift towards a more plant-based protein intake

An energy-restricted, more plant-based, protein-rich diet aligns well with the needs of older adults at risk for sarcopenic obesity while taking into account climate change. Although several studies have examined individuals who adopted a plant-based diet(Reference Craddock, Neale and Peoples62–Reference Herrema, Westerman and Dongen67), there is a lack of research on those who have not yet made this transition, particularly among older adults and especially those with obesity. In younger populations, commonly reported motivations for reducing animal-based products include animal welfare, health benefits and environmental concerns(Reference Craddock, Neale and Peoples62,Reference Janssen, Busch and Rödiger63) . A systematic review in adults aged 18–65 years further identified dietary habits, uncertainty about food choices and limited knowledge of nutritional intake and requirements as major barriers to adopting a plant-based diet(Reference Rickerby and Green64). Specifically, a focus group study found that health and appetite were the main reasons for reducing meat intake among adults aged 60 years and over(Reference Kemper65), while a large survey showed that for adults aged 45 years and over, knowledge, habits and social influences were key barriers, with health being the primary perceived benefit of eating plant-based(Reference Lea, Crawford and Worsley66). Regarding protein intake, this was found to be influenced by dietary routines, perceived health benefits and product-related factors such as taste, convenience and packaging in older adults(Reference Herrema, Westerman and Dongen67). These studies have focused specifically on promoting more plant-based eating or on increasing total protein intake, but rarely on the combination of both. We recently explored perceived facilitators and barriers to adopting a diet that is both more plant-based and protein-rich among older adults with and without obesity(Reference van Oppenraaij, Putker and van Schaik68). This study highlights the specific challenges involved in combining these two dietary goals. We revealed that health benefits and taste preferences were the most commonly reported factors influencing older adults’ willingness to adopt such a diet. Although environmental and ethical considerations were acknowledged, they were rarely primary motivators. These findings suggest that emphasising both the health advantages and the palatability of plant-based protein sources may be essential to successfully facilitate dietary change in older adult populations with and without obesity.

Although older adults at risk of sarcopenic obesity would benefit from an energy-restricted, protein-rich and more plant-based diet, its feasibility remains uncertain. Switching to more plant-based diets has been shown to decrease energy and protein intake(Reference Bakaloudi, Halloran and Rippin40). This lower protein intake is generally not of concern in the normal population, as protein intake generally exceeds the requirements. However, it may pose a risk in populations with higher protein requirements, such as older adults with obesity during a period of weight loss(Reference Weijs31,Reference Weijs and Wolfe69) . Increasing protein intake through plant-based sources often results in higher energy intake, which can complicate adherence to energy-restricted diets. This underscores a potential conflict between achieving adequate protein intake from plant-based foods and maintaining energy restriction. To date, no studies have evaluated the feasibility and effectiveness of a predominantly plant-based, protein-rich and energy-restricted diet. We are currently investigating the effects of more plant-based dietary interventions on muscle health and protein intake in older adults with and without obesity in two randomised controlled trials: 2EAT (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT06192732) and IMPACT (NCT06172725), respectively.

Concluding remarks

Although a shift toward more plant-based protein consumption is essential to meet future climate goals, this transition is still in its early stages. Older adults are particularly vulnerable to obesity, sarcopenia and sarcopenic obesity, making targeted interventions essential. Combined strategies involving tailored nutrition, particularly with adequate protein intake, and physical activity including resistance exercise, have been shown to reduce fat mass while preserving muscle mass and muscle strength. In this review, we emphasise the importance of adequate protein intake, while advocating a shift from animal-based to plant-based protein sources. Older adults may be willing to adopt more plant-based protein when these are perceived as beneficial for their health and acceptable in taste. However, the potential conflict between an energy-restricted diet and a more plant-based, protein-rich diet warrants further attention and research. To prevent and treat sarcopenic obesity in older adults and support planetary health, a shift toward more plant-based protein sources is required, while ensuring sufficient protein quantity and quality to maintain muscle health during weight loss.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge all colleagues who supported us during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author contributions

All authors drafted and reviewed the manuscript.

Financial support

None. Open access funding provided by EMGO Institute for Health and Care Research.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.