Exploring n-3 PUFA, cognitive function and telomerase-activity-dependent telomere length

Neuroscientists have recently been delving into how to prevent or mitigate the effects of ageing (see Glossary), particularly in cognitive decline (see Glossary)(Reference Fisher, Chaffee, Tetrick, Davalos and Potter1). When it comes to cognitive decline and brain senescence, leucocyte telomere length (LTL) (see Glossary) proved to be a significant biomarker(Reference Topiwala2). Along with long-chain omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 PUFA (DHA/EPA)) (see Glossary), consumption of vitamin A, vitamin B12, vitamin C, vitamin D, nicotinamide, folate, zinc, magnesium and polyphenols (see Glossary) maintains high telomere length (TL).

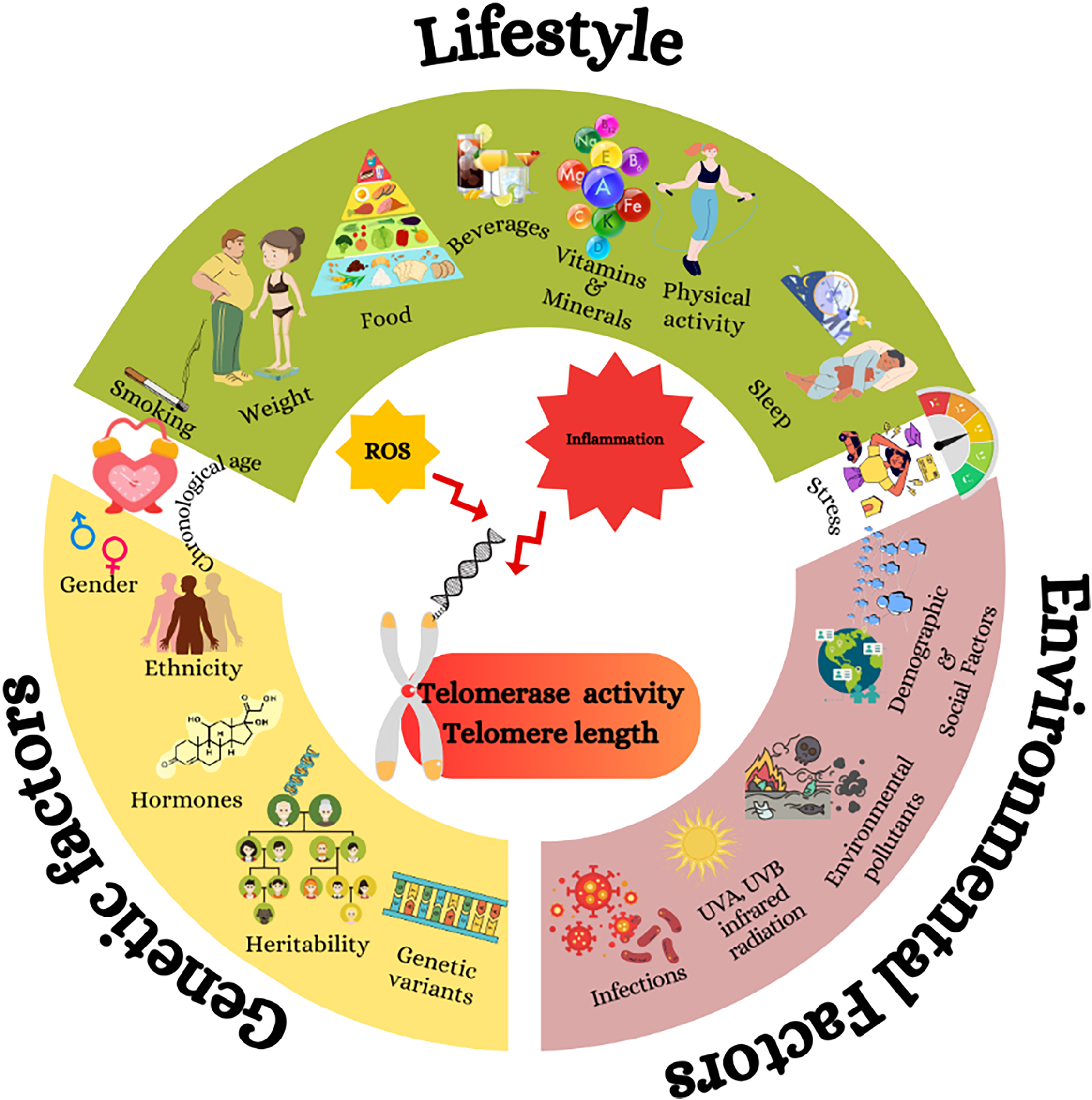

Fig. 1 The effects of genetics, environmental factors and lifespan on telomerase activity and dependent telomere length. Genetic factors such as sex and hormones, environmental factors such as infections; UVA, UVB, infrared radiation; and lifestyle factors such as dietary habits and sleeping trigger reactive oxygen species and inflammation, which cause telomere shortening by decreasing telomerase activity.(Reference Neumann, Watson, Noble, Pickett, Tam and Reddel16)

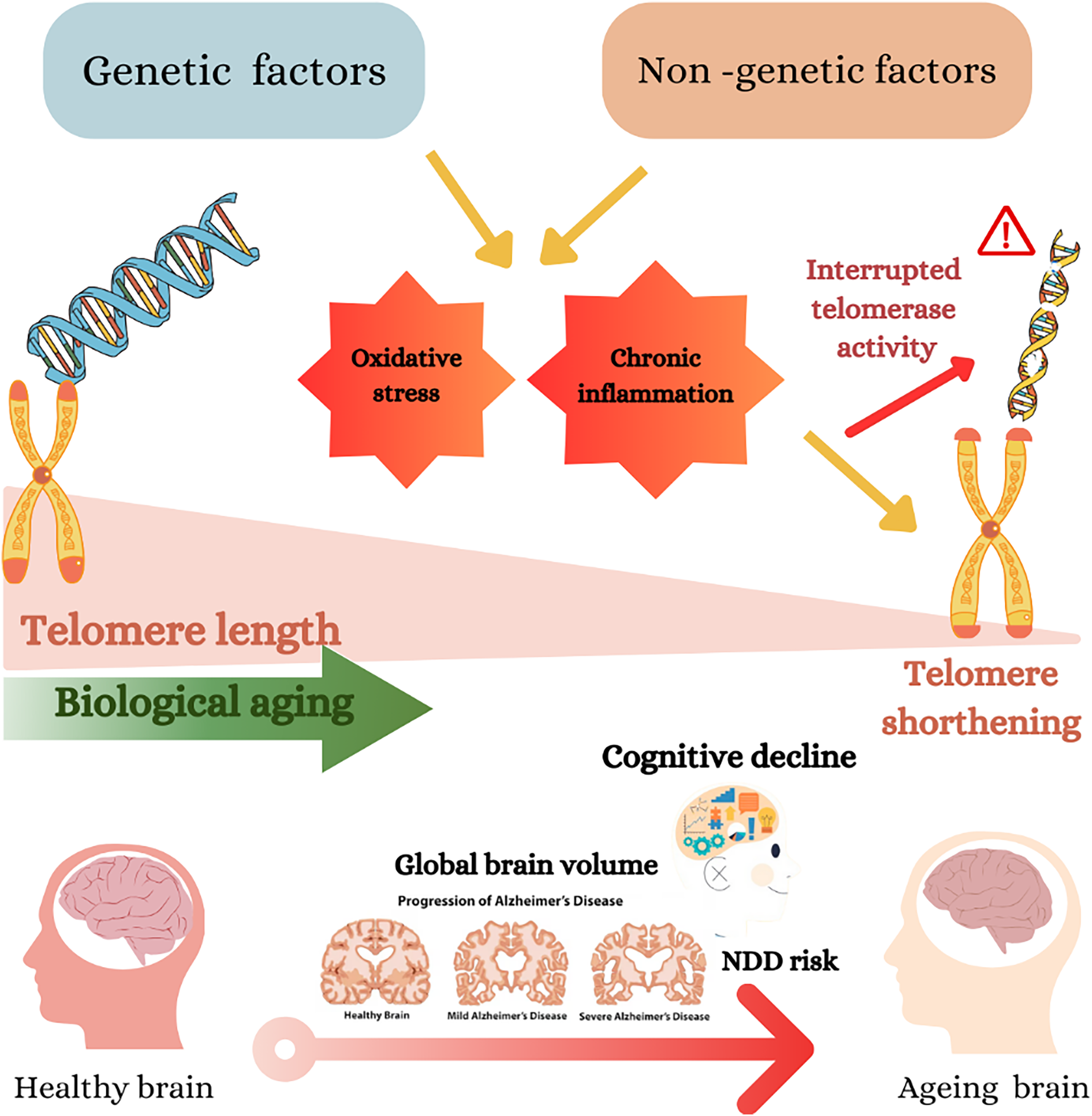

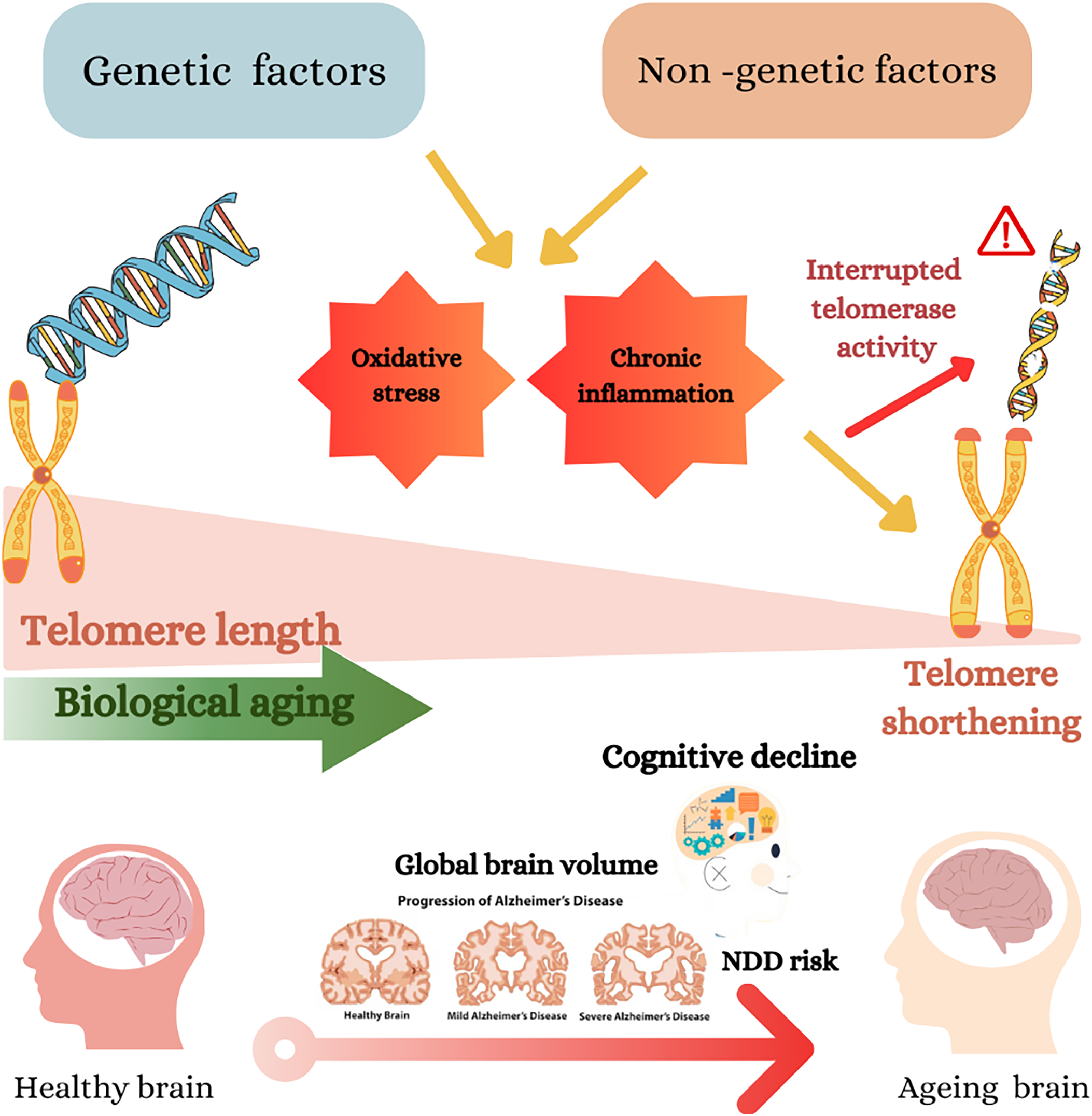

Fig. 2 Genetic and non-genetic factors impact telomere length, biological ageing and cognitive decline. Genetic and non-genetic factors may cause oxidative stress and chronic inflammation, which cause telomere shortening(Reference Neumann, Watson, Noble, Pickett, Tam and Reddel16). The shortening of telomeres accelerates biological ageing, shown as a gradient from longer telomeres (healthier) to shorter telomeres (aged)(Reference Lynch, Taub and Farfel24). The diagram further connects telomere shortening to cognitive decline and the risk of neurodegenerative diseases (NDD), including Alzheimer’s disease (AD). This is depicted by a progression of brain images from a healthy brain to severe AD, showing a reduction in global brain volume.(Reference Cao, Hou and Chenjie28)

This review explores recent evidence examining the associations between n-3 PUFA intake and its impact on cognitive function, focusing on LTL as a potential intermediary. Clinical and pre-clinical studies have commenced, unravelling the intricate interactions and correlations between dietary fatty acids and markers of cognitive wellbeing. We aim to contribute to this burgeoning field by exploring nuanced associations and shedding light on the impacts of n-3 PUFA on cognitive performance and TL.

Telomeres and their role in ageing and health

Eukaryotic cells use highly complex processes to ensure genome stability and the proper regulation of transcription and translation(Reference Valeeva, Abdulkina, Agabekian and Shakirov3). Telomeres (see Glossary) are specialised structures at the ends of linear chromosomes in eukaryotic cells. These nucleoprotein complexes ((TTAGGG) n in mammals, including humans) have several crucial functions, primarily related to the protection and stability of the genome(Reference Donate and Blasco4,Reference Smith, Pendlebury and Nandakumar5) . The linear configuration of chromosomes presents two significant challenges: the end-replication problem and the end-protection problem (for example, preventing end-to-end fusions)(Reference Smith, Pendlebury and Nandakumar5). During each replication cycle, a small fraction of telomeric DNA at the chromosome ends is lost; if this process remains unabated, chromosomal degradation and cell death are observed. Situated at the ends of the chromosomes, telomeres serve as the main solution against the end replication problem. In addition, telomeres employ mechanisms to tackle the end protection problem(Reference Topiwala2,Reference Li, Chen, Zhang, Wu and Liu6) . To prevent the genome from fusing with other parts of DNA from the hanging endpoints, telomeres behave as caps by attaching telomeric DNA via proteins(Reference Dey and Chakrabarti7). Most of the eukaryotes, but not all, engage telomerase (see Glossary) to maintain TL in certain cells(Reference Dey and Chakrabarti7). Telomerase includes the telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) (see Glossary), which is a unique human telomerase element, not expressed ubiquitously, and a telomerase RNA component (TERC) (see Glossary), enabling the template for telomere extension during de novo addition of TTAGGG repeats onto chromosome ends(Reference Lu, Vallabhaneni, Yin and Liu8). TERT is largely repressed in somatic tissues, with activity in germ cells and subsets of stem/activated immune cells(Reference Donate and Blasco4). Cancer cells synthesise telomerase to withstand extreme genomic and oxidative stress (see Glossary) and overcome their replication problem(Reference Gunes, Avila and Rudolph9).

With each cell division, imperfect copies of the DNA at the ends of each chromosome are generated, leading to the gradual shortening of telomeres. Once telomeres reach a critical length without sufficient telomerase, replication ceases, and cells enter a state known as ‘senescence’(Reference Wattis, Qi and Byrne10). However, reintroducing the telomerase enzyme can reverse senescence, highlighting the critical relationship between TL and cell senescence(Reference Zhu and van der Harst11).

The link between telomere shortening, inflammation and senescence has recently been suggested as a key factor in neurodegenerative diseases. TERT could regulate oxidative stress and inflammatory responses, thus, slowing down telomere attrition is critical for T-cell senescence and neurodegenerative diseases. Several pieces of evidence point out the modulation of TERT expression is regulated by the transcription factor nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2)(Reference Medoro, Saso, Scapagnini and Davinelli12). NRF2 promotes the expression of telomere-associated genes, including TERT, and enhances antioxidant defenses, telomere maintenance and protection against disrupted oxidative metabolism. Activation of NRF2 can repair DNA damage as well, thus contributing to telomere integrity.

A body of evidence indicates some determinant signalling pathways for telomerase activity targeting the regulation of TERT. Among them, mTOR, a serine/threonine protein kinase and member of the phosphatidyl inositol-3 kinase (PI3K)-Akt pathway, has been involved in the pathogenesis of cognitive dysfunction and in the onset of disorders and neurodegenerative diseases(Reference Wong13). It plays a key role in senescence, and the activation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway led to a decrease in telomerase activity and sped up ageing, whereas inhibition of the PI3K/ Akt/mTOR pathway increased telomerase activity and delayed aging(Reference Tan14). The pathway impacts TERT expression through transcriptional regulation, and its downstream effects influence telomere maintenance by influencing the stability and localisation of telomeric proteins such as TRF1(Reference Liu15).

Cellular oxidative stress and low-grade inflammation accelerate telomere attrition by increasing guanine oxidation (for example, 8-oxoG) within telomeric repeats, inhibiting telomerase activity, and perturbing shelterin binding. These processes contribute to DNA damage responses and senescence phenotypes relevant to neurodegeneration. We therefore centralise this mechanism here and, in later sections, reference this subsection rather than restate the same material. Alternative lengthening of telomeres (ALT), a telomerase-independent, recombination-based pathway, is introduced here alongside telomerase to complete the telomere-maintenance landscape; while most prominent in telomerase-negative tumors and immortalised lines, ALT-like recombination events have been observed in normal mammalian somatic cells, although convincing in vivo evidence that ALT alone sustains telomere elongation enough to bypass replicative limits in normal tissues remains limited(Reference Neumann, Watson, Noble, Pickett, Tam and Reddel16–Reference Blasco20).

Experimental evidence indicates that telomerase contributes to tissue maintenance with potential implications for the ageing brain. In telomerase-deficient aged mice, telomerase reactivation reversed tissue degeneration(Reference Jaskelioff21). Within the CNS, hippocampal telomerase activity has been linked to neurogenesis and mood-relevant behaviours(Reference Zhou22), highlighting a mechanistic bridge between telomere maintenance and hippocampal function, a structure central to memory and cognitive ageing.

Finally, TL, telomerase activity and epigenetic modifications are closely inter-related, and this cross-talk accompanies ageing and age-related pathologies. DNA methylation, histone methylation–acetylation and non-coding RNAs can be actors in the regulation of TERT expression in ageing and cancer, which in turn affect telomerase activity(Reference Wang23). Recent research indicates that cognitive decline in patients with Alzheimer’s is concomitant with interaction between TL and DNA methylation for triggering secondary cascades such as mitochondrial dysfunction, disrupted intercellular signalling and chronic inflammation(Reference Lynch, Taub and Farfel24).

The impacts of telomere length and telomerase activity on brain functions

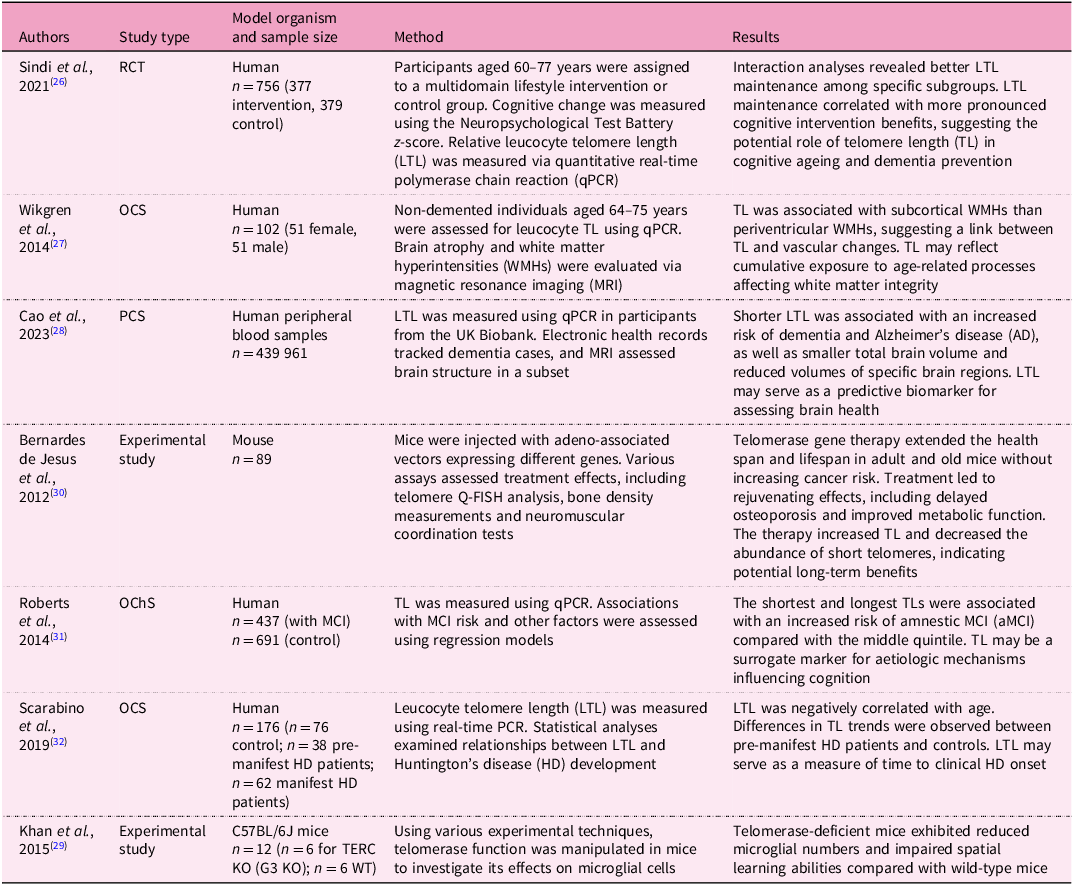

The research on cognitive function over the lifespan is an emerging interest as cognitive function changes throughout the lifespan, which is essential for healthy ageing(Reference Fisher, Chacon and Chaffee25). LTL affects global, regional and subcortical grey matter volumes, as well as cortical thickness in certain regions(Reference Topiwala2), which serves as markers for neurodegenerative disease (Box 1). TL is associated with several neurodegenerative disorders such as cognitive decline, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (see Glossary), Parkinson’s disease (PD) (see Glossary) and Huntington’s disease, as presented in Table 1 (Reference Sindi26–Reference Khan, Babcock, Saeed, Myhre, Kassem and Finsen29).

Table 1 Summary of studies investigating telomere length and cognitive health

RCT, randomised controlled trial; OCS, observational cross-sectional study; PCS, prospective cohort study; OChS, observational cohort study; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; aMCI, amnestic mild cognitive impairment; HD, Huntington’s disease; CAG, the number of trinucleotide repeats of cytosine–adenine–guanine in the HTT gene; TERC KO (G3 KO), TERC knockout mice; WT, wild type.

Genetic and non-genetic factors contribute to oxidative stress and chronic inflammation (see Glossary).

Across human studies, leucocyte telomere length (LTL) shows heterogeneous associations with cognitive trajectories and brain structure. Several cohorts report that shorter LTL or faster attrition relate to poorer cognitive performance or smaller brain volumes(Reference Harris33–Reference Mahady, He, Malek-Ahmadi and Mufson45). In contrast, other studies observe no association(Reference Insel, Merkle, Hsiao, Vidrine and Montgomery46–Reference Kaja, Reyes, Rossetti and Brown48) or inverse patterns (longer LTL associated with worse outcomes or smaller hippocampal volume)(Reference Yu49–Reference Mahoney52). These discrepancies likely reflect differences in age windows (midlife v. late-life), study design (cross-sectional v. longitudinal), LTL assay methods (monochrome qPCR, Southern blot, flow-FISH), cognitive domains tested, neurodegenerative biomarker status, APOE genotype, sociodemographic composition (race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status [SES]), sample size and statistical adjustment. Reverse causation (preclinical disease accelerating telomere attrition) and regression–dilution bias may also contribute. Overall, evidence supports a biologically plausible link between telomere biology and brain ageing, but effect sizes are modest and context-dependent, underscoring the need for standardised LTL measurement, harmonised cognitive outcomes and biomarker-stratified analyses.

Positive associations (longer LTL/slower attrition resulting in better outcomes):

In non-demented older adults, shorter LTL tracked with poorer cognitive-ageing indices(Reference Harris33). In the Nurses’ Health Study, shorter baseline LTL predicted greater 10-year cognitive decline(Reference Devore, Prescott, De Vivo and Grodstein35). Longer LTL is related to larger total and regional brain volumes in a population cohort(Reference King, Kozlitina, Rosenberg, Peshock, McColl and Garcia38). Faster telomere attrition associated with medial temporal lobe atrophy and white-matter microstructural decline(Reference Staffaroni42). Short baseline LTL predicted subsequent memory decline over about 20 years, while within-person LTL change was not informative(Reference Pudas44).

Null reports:

Community and family-based samples have also found no association between LTL and global cognition(Reference Insel, Merkle, Hsiao, Vidrine and Montgomery46–Reference Kaja, Reyes, Rossetti and Brown48).

Inverse/context-dependent findings:

In APOE ϵ3/ϵ3 carriers, longer LTL correlated with smaller hippocampal volume, suggesting genotype-specific effects(Reference Insel, Merkle, Hsiao, Vidrine and Montgomery46). In individuals along the Alzheimer’s biomarker cascade, longer baseline LTL is related to faster executive decline (stage-specific effects)(Reference King, Kozlitina, Rosenberg, Peshock, McColl and Garcia38). In Mild cognitive impairment (MCI), telomere length was related to connectome features and showed a negative association with executive function after covariate control(Reference Yu49).

Neurodegenerative disorders occur because of cell senescence, canonically triggered by LTL shortening(Reference Hayflick and Moorhead53). Cell senescence induces an imbalance in energy metabolism(Reference Tan, Hutchison, Eitan and Mattson54). Alterations in mitochondrial structure or mitochondrial DNA led to mitochondrial respiration dysfunction, which is the process that leads cells to generate energy in the form of ATP. Energy demands in the brain are notably higher than in other organs owing to its high metabolic activity. Impaired mitochondrial respiration can decrease ATP production in neurons and astrocytes, influencing various cellular processes, including neurotransmitter release, synaptic function and overall brain function. Dysfunctional mitochondria and shorter LTL, in turn, induce cellular senescence, an irreversible cell-cycle arrest linked to age-dependent physiopathology and phenotypic alterations(Reference Asghar55).

Microglia play vital roles in maintaining brain homeostasis by responding to molecular signals, such as ATP, and regulating synaptic activity by releasing immune transmitters such as cytokines and chemokines. Moreover, microglia interact with neural circuits and impact cognitive processes, including learning and memory. Microglia also regulate adult neurogenesis and influence neurogenesis throughout the lifespan(Reference Harley59). Research showed a positive correlation between microglia number and telomerase-activity-dependent TL. Dysregulation in telomerase-activity-dependent TL causes a reduction in the number of microglia(Reference Khan, Babcock, Saeed, Myhre, Kassem and Finsen29). Reports in injury models link microglial activation/state to telomerase/TL metrics, while the causal direction in humans remains unclear(Reference Flanary and Streit57).

Neurons are terminally differentiated cells that do not undergo mitosis and are regarded as post-mitotic cells(Reference Aranda-Anzaldo58). Owing to their non-replicative nature, the neurons must be maintained and aided. Although at first glance, telomere shortening, a direct result of ageing, should not be an issue for a non-dividing cell, it turns out that despite their terminal differentiation, longer telomeres and healthy maintenance of telomeres are extremely important for the health of brain cells(Reference Harley59).

Although telomerase is mainly known as a telomere-maintaining enzyme (its canonical function), TERT has suggested telomere maintenance-independent functions, named non-canonical functions, such as DNA repair, apoptosis regulation and modulation of signalling pathways(Reference Saretzki and Wan60). TERT protects neurons against apoptosis by contributing to them becoming more resistant to programmed cell death. TERT affects brain metabolism by regulating cellular redox homeostasis and abating oxidative stress. It plays a crucial role in protecting mitochondria against reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced (see Glossary) damage and improves mitochondrial function, strengthening mitochondrial membrane potential and decreasing mitochondrial ROS production(Reference Rosen, Jakobs, Ale-Agha, Altschmied and Haendeler61). Wan et al. (Reference Wang23,Reference Wan, Weir, Johnson, Korolchuk and Saretzki62) suggested that increased TERT activation improved motor functions such as gait and motor coordination in a transgenic mouse model for PD. TERT also improved the markers of autophagy and degraded toxic alpha-synuclein, which is a protein characterised by PD pathology.

Studies on the relationship between telomere length, n-3 PUFA and cognitive performance

PUFA are also known to be indispensable for the wellbeing of the brain by constituting 35% of the brain lipids(Reference Zeman, Jirak, Marek, Raboch and Zak63). Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) (see Glossary) has been particularly effective in supporting the brain against the onset of dementia and unhealthy brain ageing in completed clinical trials(Reference Kotani64–Reference Shinto67). Indeed, supplementation with DHA seems to have protective effects against brain ageing and cognitive decline(Reference Cole, Ma and Frautschy68). In addition, supplementation with n-3 docosapentaenoic acid (DPA) has also been associated with slower cognitive decline and AD(Reference de Oliveira Otto69). Interestingly, the variation in TL, irrespective of chronological age, suggests that it is a modifiable factor that is regulated and affected by other factors such as DNA damage, cell division, ageing, oxidative stress, and inflammation. As such, specific dietary constituents may be potential tools for preserving TL throughout life.

Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant-rich dietary patterns, such as Mediterranean, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH), and Mediterranean–DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND), are associated with lower systemic inflammation and oxidative stress and have been linked to slower cognitive decline and healthier brain structure in multiple cohorts. Because oxidative stress and inflammation accelerate telomere shortening, these diets provide a biologically plausible pathway whereby n-3 PUFA and broader dietary patterns may preserve telomere integrity and, in turn, support healthy cognitive ageing. Mechanistically, reduced NF-κB signaling, improved redox balance (for example, via NRF2-regulated responses), and membrane remodelling may converge on slower telomere attrition and improved neurocognitive outcomes.

One of the most relevant observations of brain ageing research pointed out that age-related cognitive decline is not only due to neuronal loss, as previously thought. Oxidative imbalance and chronic inflammation are key issues in this deterioration. Both conditions can contribute to the development of neurodegenerative diseases (see Glossary) or be a result of neuronal degeneration. Moreover, these two pathological hallmarks are linked, and it is known that oxidative stress can affect the inflammatory response. TL is affected by both oxidative stress and inflammation. In fact, oxidative stress highly addresses telomere shortening/dysfunction(Reference Blackburn70). Nutritional interventions with fish oils enriched in n-3 PUFA have shown ameliorating effects on the triad of inflammation, oxidative stress and immune cell ageing, representing important mechanisms underlying ageing. Therefore, a higher intake of n-3 PUFA can play a role in telomere maintenance and influence overall health and longevity(Reference Kiecolt-Glaser71). n-3 PUFA may protect chromosomal integrity and attenuate DNA oxidative damage by anti-inflammatory and pro-resolving actions, and modulation of redox pathways through the contribution of nuclear factor erythroid 2 (NF-E2)-related factor-2 (NRF2) (see Glossary)(Reference Golpour, Nourbakhsh, Mazaherioun, Janani, Nourbakhsh and Yaghmaei72). NRF2 plays a critical role in the antioxidant response (see Glossary) and activates the expression of cytoprotective proteins and detoxification enzymes. Anti-inflammatory properties of n-3 PUFA are associated with inhibition of proinflammatory transcription factors, leucocyte chemotaxis and oxylipin production(Reference Misheva73). Their enzymatic anti-inflammatory metabolites, such as eicosanoids and docosanoids, can influence low-grade systemic inflammatory conditions associated with endothelial dysfunction, with significant changes in the immune system. A close interaction exists among PUFA and their metabolites, telomere length and the ageing process.

The relationship between TL, n-3 PUFA and cognitive performance has garnered significant scientific interest, revealing intricate connections between diet, cellular ageing and mental health. Cassidy et al. (Reference Cassidy74) suggested that body composition and dietary factors affect leucocyte TL in the population of middle- and older-age women. Numerous studies have highlighted how specific dietary components can influence telomere attrition, with particular attention to the benefits of monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA; see Glossary) and PUFA, especially within dietary patterns such as the Mediterranean diet, known for its high content of these nutrients(Reference Öngel, Yıldız, Akpınaroğlu, Yilmaz and Özilgen75–Reference Marti77). Such diets have been associated with slower telomere shortening and, consequently, decelerated ageing processes. The results of a prospective cohort study on 608 ambulatory outpatients by Farzareh et al. (Reference Farzaneh-Far, Lin, Epel, Harris, Blackburn and Whooley78) indicated that higher n-3 PUFA levels were positively correlated with a smaller decrease in TL over a 5-year period. Even after adjusting for various confounders, the association between higher n-3 PUFA may play a role in slowing the ageing process at the cellular level.

A recent study utilising Mendelian-randomisation analysis aimed to investigate how MUFA, PUFA, and saturated fatty acids (SFA; see Glossary) affect ageing by comparing proxy indicators of the frailty index (FI), facial ageing (FA), and TL(Reference Mather, Jorm, Anstey, PMilburn, Easteal and Christensen51). While MUFA and PUFA were found to be halting the progress of ageing, SFAs were detected to hasten the process. No significant correlations were detected among FI and FA, and MUFA, PUFA, and SFAs. The main indicator and the molecular biomarker for the effect of ageing was TL, and while MUFA and PUFA were correlated with higher TL, SFA had an inverse correlation.

Reduction in TL with increasing age is a common phenomenon in all somatic cells. However, recent studies have suggested that TL can also be enhanced in somatic cells(Reference Shlush79,Reference Svenson80) . Such a reverse attrition difference in TL was attributed to changes in oxidative stress. Thus, supplementation with n-3 PUFA provoked significant changes in TL, which were associated with effects on oxidative stress, inflammation, and immune cell ageing, which were improved with dietary modifications(Reference Kiecolt-Glaser81). Healthy lifestyle and anti-inflammatory diets may reduce oxidative stress and thus indirectly support telomere maintenance via canonical pathways; the effects on ALT in normal tissues are unproven(Reference Ng82). A proposed working mechanism of ALT is a controlled homology-directed repair mechanism created in a controlled manner. Another suggested model explaining ALT is the formation of Holliday junctions at the T-loop structures in mammalian DNA, where the loop is formed by the 3′ overhang fusing to its preceding strand(Reference Kiecolt-Glaser71).

A meta-analysis study by Ali et al.

(Reference Ali, Scapagnini and Davinelli83) put forward that n-3 PUFA supplementation may contribute to telomere maintenance and, by extension, influence ageing and disease prevention despite the limited number of clinical studies. The researchers suggested that the protective effects of n-3 PUFA on telomeres may be attributed to their anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. These fatty acids modulate inflammatory pathways and enhance antioxidant defenses, potentially through the activation of NRF2 and the regulation of antioxidant properties. The convergence of findings from studies on TL, n-3 PUFA and cognitive performance suggests a synergistic relationship (Box 2). The anti-inflammatory and antioxidative effects of n-3 PUFA may contribute to the preservation of TL, which in turn could mitigate cognitive decline. A study by O’Callaghan et al.

(Reference O’Callaghan, Parletta, Milte, Benassi-Evans, Fenech and Howe84) revealed that older adults with MCI who received eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA; see Glossary) and DHA supplements had reduced telomere shortening compared with those who took n-6 linoleic acids supplements. Wu et al.

(Reference Wu, Wu, Chen, Zhuang, Zhang and Jiao85) found that DHA supplementation significantly attenuated telomere attrition in blood leucocytes and various tissues, suggesting a protective effect against telomere shortening. The follow-up study with mice supplemented with DHA led to reduced ageing phenotypes, such as lower

![]() ${\rm{\beta }}$

-galactosidase activity, indicative of reduced cellular senescence. DHA intervention reduced telomere attrition-induced DNA damage as indicated by lower γ-H2AX levels and enhanced recruitment of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1), a key protein in DNA repair. DHA suppressed the NF-

${\rm{\beta }}$

-galactosidase activity, indicative of reduced cellular senescence. DHA intervention reduced telomere attrition-induced DNA damage as indicated by lower γ-H2AX levels and enhanced recruitment of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1), a key protein in DNA repair. DHA suppressed the NF-

![]() ${\rm{\kappa }}$

B/NLRP3/caspase-1 pathways, suggesting anti-inflammatory effects. DHA also improved mitochondrial function, reduced ROS accumulation and decreased markers of oxidative stress by improving mitochondrial homeostasis, and thus reduced mitochondrial damage. All these effects are crucial to maintaining healthy ageing and cognitive functions (see Glossary). Barden et al.

(Reference Barden86) also stated that the potential impact of n-3 acids on the increase of telomere length, adjusted for neutrophil count, may be associated with diminished oxidative stress and enhanced elimination of neutrophils with shorter telomeres from the circulation. All these animal and human studies reveal that there is an association between

${\rm{\kappa }}$

B/NLRP3/caspase-1 pathways, suggesting anti-inflammatory effects. DHA also improved mitochondrial function, reduced ROS accumulation and decreased markers of oxidative stress by improving mitochondrial homeostasis, and thus reduced mitochondrial damage. All these effects are crucial to maintaining healthy ageing and cognitive functions (see Glossary). Barden et al.

(Reference Barden86) also stated that the potential impact of n-3 acids on the increase of telomere length, adjusted for neutrophil count, may be associated with diminished oxidative stress and enhanced elimination of neutrophils with shorter telomeres from the circulation. All these animal and human studies reveal that there is an association between

![]() $n$

-3 PUFA, TL and cognitive outcomes.

$n$

-3 PUFA, TL and cognitive outcomes.

Discussions of findings and potential mechanisms

TL is a critically important parameter in all cells for optimal functioning, even in terminally differentiated post-mitotic neuronal cells, as demonstrated in a recent study comparing astrocytes and motor neurons generated with different TL(Reference Harley59). Cells with shorter TL showed elevated inflammation, higher cellular senescence and increased DNA damage. Combined with highly substantial evidence accumulating in the last decade that non-canonical functions of TERT are associated with preserving the genome against sources of DNA damage, including oxidative stress, and the fact that neither the correlation of telomeres nor TERT is properly elucidated, telomeres and TERT emerge as highly promising research for nutrition, ageing and therapeutic medicine.

Another promising research related to non-canonical cellular TERT mechanisms is the capacity for MUFA and PUFA to mitigate telomere attrition. The beneficial effects of different diets on maintaining TL have already been discovered(Reference Öngel, Yıldız, Akpınaroğlu, Yilmaz and Özilgen75). However, pinpointing the exact sources of nutrients leading to this effect and the exact molecular mechanisms underlying it are not well elucidated.

Interestingly,

![]() $n$

-3 PUFA supplementation has been associated with pathways affecting TERT expression and telomerase activity. The mTOR pathway is known to be activated by multiple factors, including insulin and nutrients. Both in vitro and in vivo studies have reported mTOR as an omega-3 target in different pathological conditions(Reference Shirooie87). In fact, n-3 PUFA inhibit mTOR through different mechanisms, including interference with the PI3K/Akt pathway. The regulatory role of the mTOR signalling pathway has been closely associated to the prevention of major neurological diseases, considering its ability to modulate autophagy, protein synthesis in neurons and the maintenance of synaptic plasticity underlying memory formation. Furthermore, the inhibition of mTOR could exert a protective effect on the brain against inflammation.

$n$

-3 PUFA supplementation has been associated with pathways affecting TERT expression and telomerase activity. The mTOR pathway is known to be activated by multiple factors, including insulin and nutrients. Both in vitro and in vivo studies have reported mTOR as an omega-3 target in different pathological conditions(Reference Shirooie87). In fact, n-3 PUFA inhibit mTOR through different mechanisms, including interference with the PI3K/Akt pathway. The regulatory role of the mTOR signalling pathway has been closely associated to the prevention of major neurological diseases, considering its ability to modulate autophagy, protein synthesis in neurons and the maintenance of synaptic plasticity underlying memory formation. Furthermore, the inhibition of mTOR could exert a protective effect on the brain against inflammation.

![]() $n$

-3 PUFA are suggested to possess the ability to restore NRF2 function, maintain a proper redox balance and preserve telomere length during ageing. In particular, oxidised lipid metabolites as eicosanoids and docosahexanoids coming from the enzymatic action of cyclooxygenases, lipoxygenases and cytochrome P450 over EPA and DHA, are suggested as effective NRF2 inducers(Reference Davinelli, Medoro, Intrieri, Saso, Scapagnini and Kang88). These metabolites are lipid mediator triggers for the NRF2 pathway by quickly reacting with specific cysteine residues of KEAP1, which is the endogenous inhibitor of NRF2.

$n$

-3 PUFA are suggested to possess the ability to restore NRF2 function, maintain a proper redox balance and preserve telomere length during ageing. In particular, oxidised lipid metabolites as eicosanoids and docosahexanoids coming from the enzymatic action of cyclooxygenases, lipoxygenases and cytochrome P450 over EPA and DHA, are suggested as effective NRF2 inducers(Reference Davinelli, Medoro, Intrieri, Saso, Scapagnini and Kang88). These metabolites are lipid mediator triggers for the NRF2 pathway by quickly reacting with specific cysteine residues of KEAP1, which is the endogenous inhibitor of NRF2.

Among mechanisms to control TERT gene regulation, some dietary compounds, such as n-3 PUFA, can alter normal epigenetic states, influencing gene expression, development, metabolism and phenotype. Diet components can also modulate epigenetic modifications, resulting in reverse abnormal gene activation or silencing. Supplementation with n-3 PUFA influence gene methylation and modulates the expression of several key pathways associated with the onset of cognitive decline, including those related to inflammation, immune responses, and lipid metabolism(Reference González-Becerra89). DHA and EPA are suggested as DNA methylation modulators owing to their ability to correct aberrant acetylation and methylation profiles and restore normal patterns. This effect of repair is a key epigenetic mechanism that regulates gene expression in the brain.

Gaps in literature and areas for future research

The telomeres need to withstand oxidative stress and other possible causes of DNA damage even when the chromosome is not being replicated. Mechanistic pathways are summarised in the ‘consolidated mechanisms’ subsection(95,96). Considering the recent findings of how TERT is also somehow related to neuronal health by non-canonical means, the underlying mechanisms need to be fully resolved(Reference Saretzki and Wan60). A recent similar experiment was designed by creating neurons with different TL from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), and indeed, a correlation between short TL and neurodegenerative diseases was found(Reference Harley59). However, the mechanism that can explain this correlation is still not clear.

Among many nutrients, MUFA and PUFA help protect the brain against ageing. A significant amount of the molecular constitution of brain lipids is PUFA; however, the molecular process of how the consumption of PUFA protects against brain ageing is not well explained in relation to the protective effect on TL. While fish oil, especially DHA and EPA, was observed to protect cells against oxidative stress in some studies, long-term consumption of fish oil was observed to increase oxidative stress and even promote ageing(Reference Tsuduki, Honma, Nakagawa, Ikeda and Miyazawa92,Reference Lima Rocha93) . This counter relation of PUFA promoting oxidative stress and ageing on their long-term intake illustrates how the exact mechanism of PUFA, ageing, and TL still needs to be well studied, with research focusing on lipid metabolism.

Concluding remarks

Evidence linking n-3 PUFA, epigenetic/signalling modulation and broader anti-inflammatory and antioxidant patterns to telomere biology and cognitive ageing is biologically plausible and supported in several cohorts, yet findings are heterogeneous across designs, age windows, assays and populations. Effect sizes appear modest and may depend on neurodegenerative biomarker status, APOE genotype, and sociodemographic context; thus, claims of uniform benefit are not warranted.

To clarify causality and resolve discrepancies, future work should (i) standardise LTL measurement and reporting across platforms (qPCR, Southern blot, flow-FISH), (ii) harmonise cognitive outcomes and integrate multimodal magnetic resnonace imaging (MRI), (iii) adopt longitudinal, life-course designs with pre-specified analyses, (iv) stratify by biomarkers (for example, amyloid/tau) and APOE, (v) ensure diverse sampling with SES/race adjustments, and (vi) complement observational data with median randomization (MR) and rigorously powered dietary or supplementation trials. These steps will determine when, and for whom, dietary strategies may help preserve telomere integrity and support brain health.

Acknowledgements

We confirm that Grammarly was used for language editing only.

Authorship

All authors contributed equally to the manuscript, as outlined below:

C.Y.: conceptualisation, study design, original draft preparation, review and editing, and visualisation. C.A.: study design, original draft preparation, review, and editing. I.M.: study design, original draft preparation, supervision, review, and editing.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.