Introduction: Tension in CSSPs

Cross-sector social partnerships (CSSPs) refer to “cross-sector projects formed explicitly to address social issues and causes” (Selsky & Parker, Reference Selsky and Parker2005, p. 850). CSSPs generally include organizations from public, private and nonprofit sectors focused on economic and community development, social services and public health (Selsky & Parker, Reference Selsky and Parker2005). Such relationships often embody tension (e.g., Googins & Rochlin, Reference Googins and Rochlin2000; Waddell & Brown, Reference Waddell and Brown1997; Westley & Vredenburg, Reference Westley and Vredenburg1997) over differing sectoral approaches to creating value for beneficiaries (Le Ber & Branzei, Reference Le Ber and Branzei2010), issues surrounding power and control (Selsky & Parker, Reference Selsky and Parker2005) and differences in participants’ structures and goals (Babiak & Thibault, Reference Babiak and Thibault2009).

In response to calls for research to help resolve such tensions (e.g., Austin, Reference Austin2010; Di Domenico et al., Reference Di Domenico, Tracey and Haugh2009), we map where, structurally, tensions occur within the interorganizational dynamics of CSSPs. We posit that CSSP participants face different tensions in different aspects of the partnership. Tensions exist within individual organizations as they debate the need for partnering and weigh the resources required against benefits. Tensions exist between partners as they align agendas or recall previous encounters. Tensions exist within the newly formed entity over leadership or decision-making. And tensions occur between that newly formed collective entity and external beneficiaries over needs and impact.

Tension refers to “inner striving, unrest or imbalance” or “a latent state of hostility or opposition between groups or individuals” (Merriam-Webster). We are not referring to fundamentally different world views among partners forced to work together. Such tensions are understandable. We instead seek to capture potentially avoidable tensions that emerge between seemingly well-aligned partners to avoid an accumulation of frustrations or “latent hostility or opposition” that could lead to dissolution.

First, we explain our four-tiered conceptualization of CSSPs. We then provide examples of tensions in a CSSP responding to the influx of Ukrainian refugees to Romania in 2022. We compare our findings with those in the literature and consider how our classification system benefits CSSP research and practice.

Literature Review

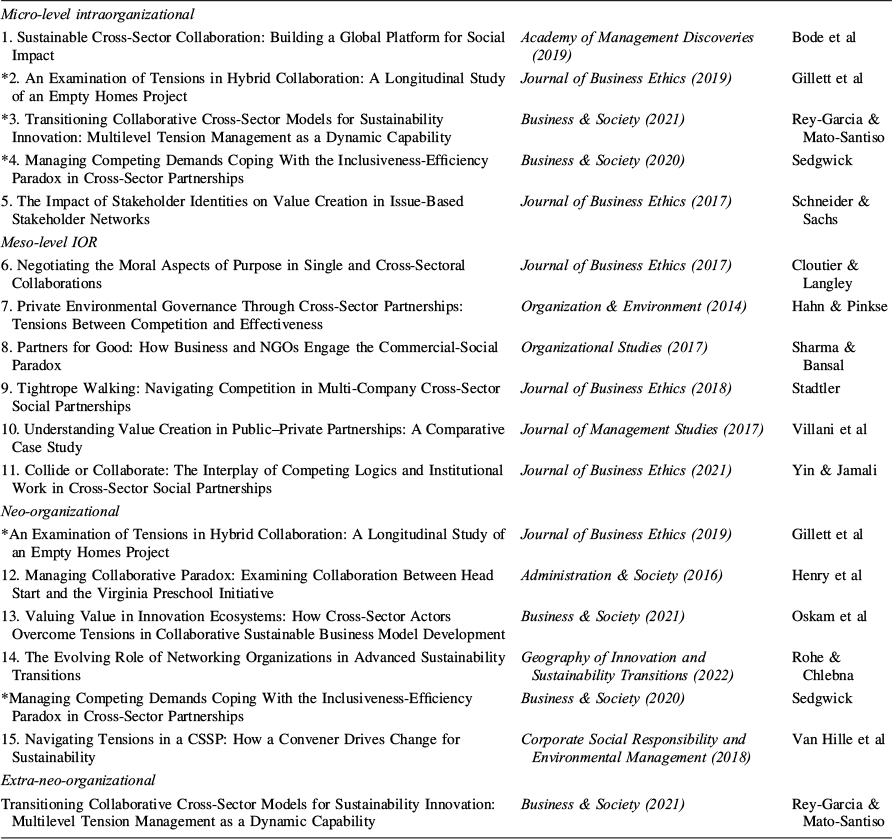

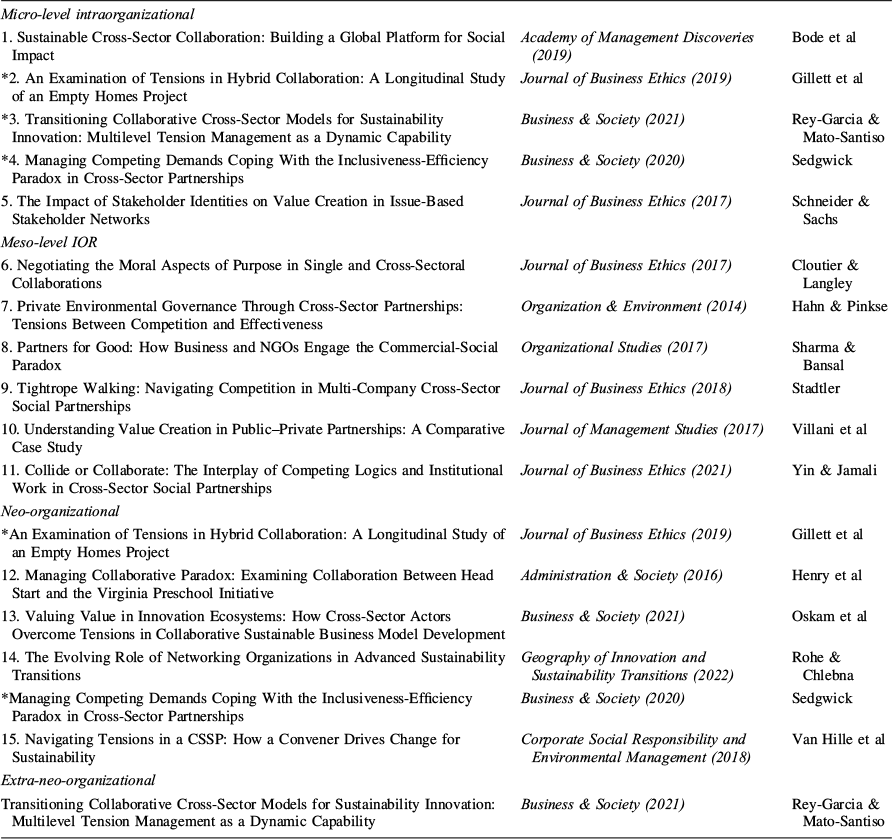

Our review of the literature began with a search of Google Scholar and Worldcat by abstract keywords (and variations) of CSSP, tension, management and interorganizational relationships (IORs) for the most cited research explicitly focused on tensions in CSSPs using Publish or Perish (Harzing, Reference Harzing2010). We cross-listed results with the Australian Business Deans Council journal ranking, keeping only those ranked “A” or “B.” We include that list of articles in Table 1.

Table 1 Literature search resulting articles

|

Micro-level intraorganizational |

||

|

1. Sustainable Cross-Sector Collaboration: Building a Global Platform for Social Impact |

Academy of Management Discoveries (2019) |

Bode et al |

|

*2. An Examination of Tensions in Hybrid Collaboration: A Longitudinal Study of an Empty Homes Project |

Journal of Business Ethics (2019) |

Gillett et al |

|

*3. Transitioning Collaborative Cross-Sector Models for Sustainability Innovation: Multilevel Tension Management as a Dynamic Capability |

Business & Society (2021) |

Rey-Garcia & Mato-Santiso |

|

*4. Managing Competing Demands Coping With the Inclusiveness-Efficiency Paradox in Cross-Sector Partnerships |

Business & Society (2020) |

Sedgwick |

|

5. The Impact of Stakeholder Identities on Value Creation in Issue-Based Stakeholder Networks |

Journal of Business Ethics (2017) |

Schneider & Sachs |

|

Meso-level IOR |

||

|

6. Negotiating the Moral Aspects of Purpose in Single and Cross-Sectoral Collaborations |

Journal of Business Ethics (2017) |

Cloutier & Langley |

|

7. Private Environmental Governance Through Cross-Sector Partnerships: Tensions Between Competition and Effectiveness |

Organization & Environment (2014) |

Hahn & Pinkse |

|

8. Partners for Good: How Business and NGOs Engage the Commercial-Social Paradox |

Organizational Studies (2017) |

Sharma & Bansal |

|

9. Tightrope Walking: Navigating Competition in Multi-Company Cross-Sector Social Partnerships |

Journal of Business Ethics (2018) |

Stadtler |

|

10. Understanding Value Creation in Public–Private Partnerships: A Comparative Case Study |

Journal of Management Studies (2017) |

Villani et al |

|

11. Collide or Collaborate: The Interplay of Competing Logics and Institutional Work in Cross-Sector Social Partnerships |

Journal of Business Ethics (2021) |

Yin & Jamali |

|

Neo-organizational |

||

|

*An Examination of Tensions in Hybrid Collaboration: A Longitudinal Study of an Empty Homes Project |

Journal of Business Ethics (2019) |

Gillett et al |

|

12. Managing Collaborative Paradox: Examining Collaboration Between Head Start and the Virginia Preschool Initiative |

Administration & Society (2016) |

Henry et al |

|

13. Valuing Value in Innovation Ecosystems: How Cross-Sector Actors Overcome Tensions in Collaborative Sustainable Business Model Development |

Business & Society (2021) |

Oskam et al |

|

14. The Evolving Role of Networking Organizations in Advanced Sustainability Transitions |

Geography of Innovation and Sustainability Transitions (2022) |

Rohe & Chlebna |

|

*Managing Competing Demands Coping With the Inclusiveness-Efficiency Paradox in Cross-Sector Partnerships |

Business & Society (2020) |

Sedgwick |

|

15. Navigating Tensions in a CSSP: How a Convener Drives Change for Sustainability |

Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management (2018) |

Van Hille et al |

|

Extra-neo-organizational |

||

|

Transitioning Collaborative Cross-Sector Models for Sustainability Innovation: Multilevel Tension Management as a Dynamic Capability |

Business & Society (2021) |

Rey-Garcia & Mato-Santiso |

*Applied to two different levels

Tensions Within Participating Organizations

“Micro-level” or “intra-organizational” tensions occur within participating organizations as they decide whether or not to partner. Tensions often arise around employee interest, as they ultimately shoulder the burden of partnering (Bode et al., Reference Bode, Rogan and Singh2019). They need to determine whether the issue is significant and whether it requires this partnership, a different partnership, or is better addressed independently. They also need to decide who will represent them in the partnership, if they have the proper authority, and whether they have the time and energy to serve. Partnerships can require either higher-level administrative representation or lower-level project manager engagement.

Positive prior experiences with partners and partnerships may reduce such internal tensions (Gillett et al., Reference Gillett, Loader, Doherty and Scott2019). Partners also consider their organization’s needs and the perception of those needs by potential collaborators. Some partners seek organizations that provide legitimacy, power, influence or resources. Others seek leadership. Finally, potential partners seek to understand their identity in the partnership, including which responsibilities and tasks they can and cannot deliver and the power they have in that process. Sedgwick (Reference Sedgwick2016) refers to this as tension between the “organizational” and “collaborative” identity. The root of such tensions occurs as organizations grapple internally with ensuring their own missions are not lost in the partnership’s mission. A pre-existing “strong” identity may inhibit the potential value of the partnership (Schneider & Sachs, Reference Schneider and Sachs2017).

Tensions Between Participating Organizations

Dyadic tensions between partners over differences in power, goals, values and purpose dominate the literature. Hahn & Pinske (Reference Hahn and Pinkse2014) suggested rivalry can undermine effectiveness when partners from the same sector engage in a CSSP, as individual organizations compete to have their agenda define the partnership’s goals. If competition is fierce enough, partners may leave or reduce cooperation to avoid providing advantages to rivals (Hahn & Pinske, Reference Hahn and Pinkse2014; Rey-Garcia & Mato-Santiso, Reference Rey-Garcia, Mato-Santiso and Felgueiras2021). Sharma and Bansal (Reference Sharma and Bansal2017) found partners unable to negotiate a social-commercial venture were less successful than partners that treated the situation as something they could alter. These values and norms expose different institutional or cultural logics. Multiple institutional logics suggest complexity, a “key characteristic” of social partnerships and a source of tension (Villani et al., Reference Villani, Greco and Phillips2017; Yin & Jamali, Reference Yin and Jamali2021). Stadtler (Reference Stadtler2018) clarified that without long-term incentives, such differing logics erode previous commitments and slow progress and reduces morale. Fundamental differences in perceptions of a partnership’s ultimate purpose may be a “fatal flaw” for CSSPs (Cloutier & Langley, Reference Cloutier and Langley2017). Indeed, uncertainty itself creates tension (Villani et al., Reference Villani, Greco and Phillips2017).

Tensions Within the Newly Formed Partnership

The next set of tensions move beyond those felt within or between partners, to those felt within the collective. Oskam et al. (Reference Oskam, Bossink and de Man2021) identified three levels of tension within general partnerships. First, while the partnership itself turns collective resources into something more valuable, individual participating organizations may benefit more than the collective. Second, while the partnership may be designed to achieve more than any organization could alone, individual organizations may still want to ensure benefits to themselves, particularly if they perceive that the partnership’s success is due in large part to their inputs. The third tension addresses perceived fairness across organizations.

Henry et al. (Reference Henry, Rasche and Möllering2022) identified a tension between inclusiveness and efficiency. A key tenet of the CSSP they studied was a deep respect for all participating organizations’ opinions and ideas. But the lack of efficiency this posed threatened the viability of the partnership. A related tension refers to facilitators who must balance between directing and maintaining neutrality (Van Hille et al., Reference Van Hille, de Bakker and Ferguson2018). Gillett et al. (Reference Gillett, Loader, Doherty and Scott2019) identify two additional sources of tension. First, as collaborations mature, they codify practices and structures. This created tension in their case as the partnership struggled with meeting frequency and duration. As a result, decision-making slowed and the collaboration lost its initial flexibility. Turnover also became a source of tension regarding how to fill roles and who would be the new “champions of the cause.” Rohe and Chlebna (Reference Rohe and Chlebna2022) also found turnover prevented partnership stabilization. Both of these tensions, bureaucracy and turnover, emerge over time as the collaboration “matures.”

Tensions Between the New Partnership and External Beneficiaries

Tensions can exist between the CSSP and the external beneficiaries it aims to help. Partnerships face external challenges since they exist in an open system and were likely created to ameliorate social problems intractable enough that no organization could solve them independently. CSSPs inherently interact with the cause ecosystem, typically fraught with tension given the nature of so-called wicked challenges (Churchman, Reference Churchman1967; Rittel & Webber, Reference Rittel and Webber1973). Only one article reviewed explicitly note this tension, pointing out that, “… direct users and indirect beneficiaries (i.e., professional and nonprofessional caregivers), and grassroots groups speaking for people at risk or in situation of dependency (neighbors, support groups, mutual aid networks, etc.) were only indirectly represented in the evolving collaborative business models” (Rey-Garcia & Mato-Santiso, Reference Rey-Garcia, Mato-Santiso and Felgueiras2021, p. Reference Rey-Garcia, Mato-Santiso and Felgueiras1159). Neglecting informal actors may be why CSSPs struggle with impact assessment. Capturing, measuring and conveying CSSP impact proves problematic (Benjamin et al., Reference Benjamin, Ebrahim and Gugerty2023) despite being critical for the partnership’s legitimacy to communities, funders and policy makers.

External funding also requires addressing additional stakeholders (e.g., local, state, and/or federal governments). For example, a CSSP working to improve immigration issues might play a role in agenda setting at the state level, while they also seek funding and serve their constituents (Landolt et al., Reference Landolt, Goldring and Bernhard2011). As the CSSP becomes more self-actualized, this final level of tension may take center stage as the tensions within and between partners and/or at the level of the whole entity diminish.

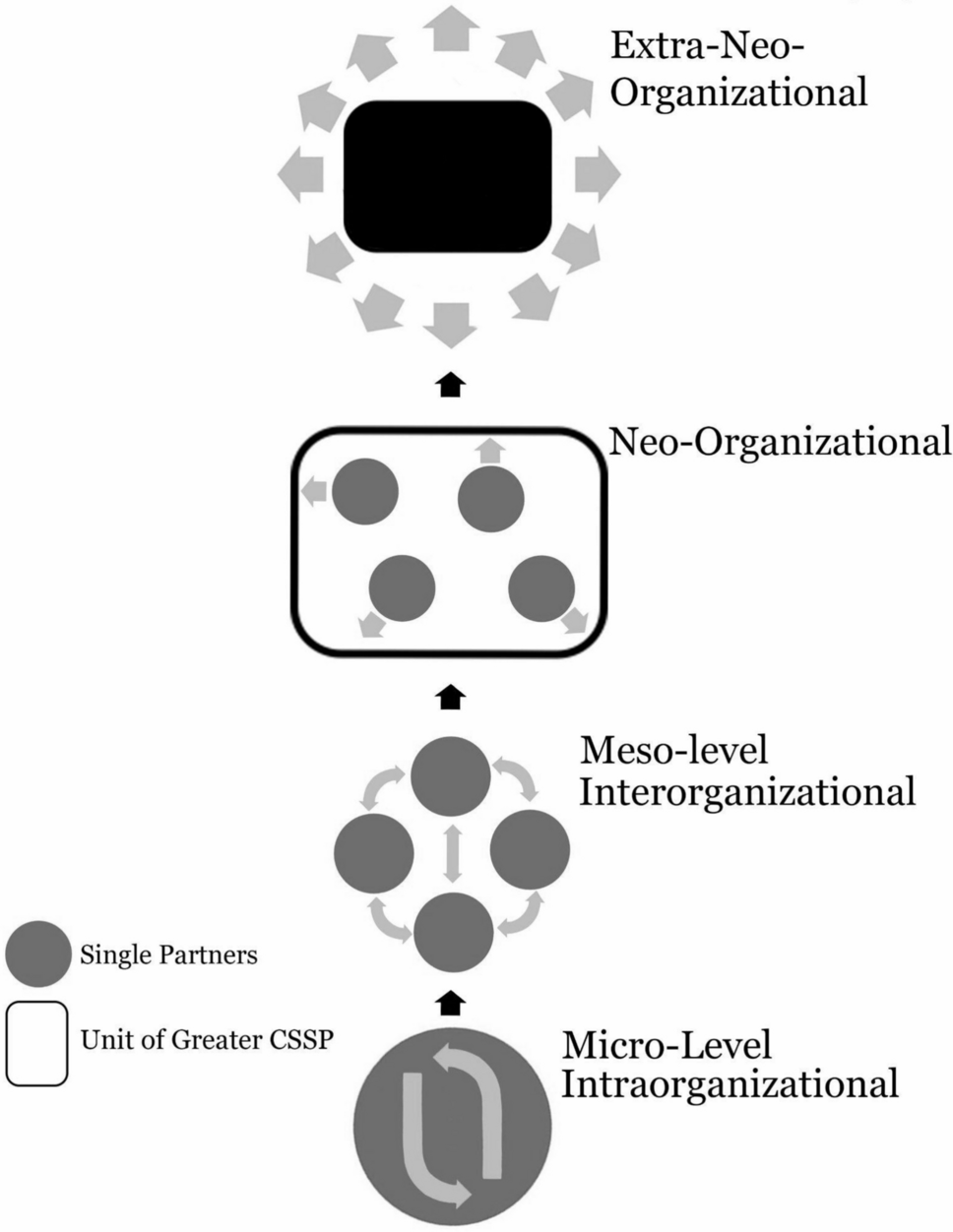

Below, we shape the literature above into a four-tiered structural conceptualization of CSSPs (Fig. 1) to demonstrate that CSSPs contain dynamics within organizations, interactions between organizations, activities within the newly formed partnership and relationships between the task force and external beneficiaries.

Fig. 1 Levels of tension in CSSPs

Following this exercise of mapping each level of tension from the existing literature on cross-sector collaboration, we next conducted our primary research with the task force in an effort to understand how they spoke about tensions. In other words, would these levels emerge naturally in an “after action review” of their work?

Methods

Context

This case study relies on field work and interviews conducted in a mid-size wealthy Romanian town with a university, thriving tech industry and active civil society. Within days after the full-scale Russian invasion, the town received hundreds of thousands of refugees (Alexandra et al., Reference Alexandra, Cosciug, Krychenko and Cosciug2023). Most were transiting the country via train, bus and flight connections, stopping only for a day or two before moving on. Yet, the volume was enormous and the Municipality quickly initiated a task force as part of a nation-wide call to coordinate local level responses. Our research question thus explores how participants in the task force spoke about tensions among participating entities, and whether their responses would align with the four-tiered model of levels we articulated. The area has a long history of ties with Ukraine although migration was historically moderate. While the town primarily served as a transit hub for refugees between Ukraine and Western Europe (Cosciug, Reference Cosciug2024; UNHCR, 2023), it became one of the top destinations for displaced Ukrainian refugees due to generous government reimbursements for refugee-related housing costs.

Case Selection

We rely on a single-site case study design, appropriate when seeking to test or build theory (Yin, Reference Yin2017), to capture in-depth the activities of the responding task force. Our approach proves useful in isolating the dynamics and actions of individual actors within this context. Tu (Reference Tu2021) used a similar approach to analyze nonprofits in the provision of social services in China, which seems appropriate for answering the “whys” and “hows” of the task force (Lee, Reference Lee1989). The size of our task force may be small (n = 11), but our interviews include all the key players and are consistent with similar case research (see Campbell & Warner, Reference Campbell and Warner2016; Tu, Reference Tu2021; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Liu and Wang2024).

While this case study takes place in a unique context bound by time, many of the processes that occur in this task force are likely to occur in other CSSPs, so it is possible to generalize from a single-site case study (Gioia et al., Reference Gioia, Corley and Hamilton2013). We are also naturally trying to generalize to theory (Bansal & Corley, Reference Bansal and Corley2011; Gioia et al., Reference Gioia, Corley and Hamilton2013). Our purpose is to expose the various levels within which important CSSP dynamics take place. We believe our findings are generalizable to the many different types of CSSPs highlighted in the literature review. Our findings clarify and expand existing theory about CSSPs by providing rich description using the voice of our subjects (Harley & Cornelissen, Reference Harley and Cornelissen2022; Johns, Reference Johns2006; Nowell & Albrecht, Reference Nowell and Albrecht2019) to clearly see the four levels inherent in such partnerships.

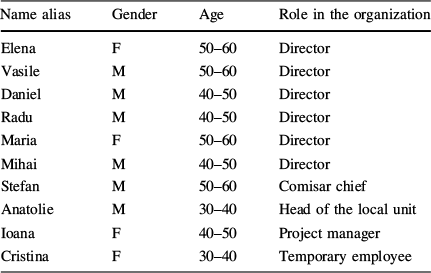

Data Collection

Field work began in summer 2023 with interviews at border towns in Romania to learn how initial responders coped with the massive influx of refugees. These initial leads were provided by researchers, focused on refugees in Romania, through professional networks. This provided us with an understanding of the context. We started by interviewing two practitioners from local NGOs and three academics, leading to a snowball sampling approach that resulted in an additional 20 one-hour interviews (in English) with academics, local, regional and international NGO representatives and government officials involved in the response. These respondents reported the complexities of the situation: increased workload, identifying and building partnerships, working within cross-sectoral task forces and the difficulties of constant change in the flows of refugees and their needs. This shaped the direction of our research by leveraging the “overlap of data analysis with data collection” (Eisenhardt, Reference Eisenhardt1989, p.538). More importantly, many respondents in this first round of research pointed to a particular task force as an example of a seemingly effective response.

We then focused on that task force for our case study, embracing a convenience sample strategy (Ruiz & Ravitch, Reference Ruiz and Ravitch2023). We worked with a Romanian partner to ensure representation of all of the key member organizations sitting on that task force. Leaders were recruited purposefully, targeting the members of the task force that we learned about from the previous round of contextual interviews (Krasniqi, Reference Krasniqi2024). We revised our protocol based on insights from round one and conducted a second round of interviews (in Romanian) to probe more deeply in their native language. In fall 2023, we obtained a list of all the task force members from one of the coordinators and interviewed representatives from each organization (with two exceptions) which included police, transit police, emergency medical response teams and the regional emergency management organization (as governmental representatives); social workers, a refugee civic center, an association for the underprivileged, a soup kitchen and an association of pharmacists (NGO representatives); and a private firm working on housing.

These 1–2-h interviews were conducted in Romanian, the native language of our respondents, by our Romanian author, audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. They were then translated into English with naturalized or intelligent verbatim translation (McMullin, Reference McMullin2023) to improve readability. We used this set of interviews to develop the narrative below. Each of these interviews began with “grand tour”-type questions about their background and experiences before targeting specifically the topics reported below through open-ended questioning.

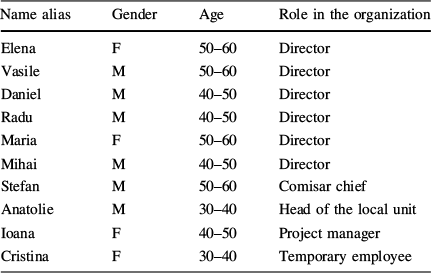

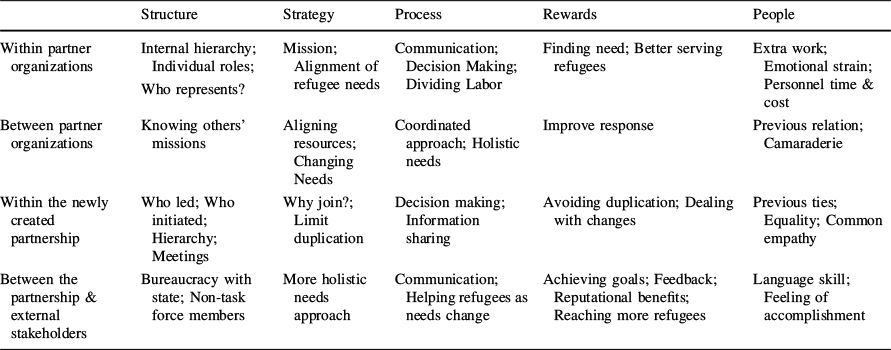

Data Analysis

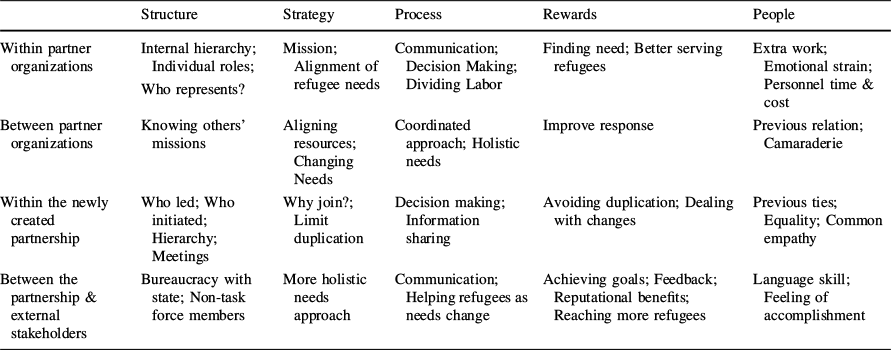

We open-coded all of the interviews to develop “a wealth of codes with which to describe the data” (Vollstedt & Rezat, Reference Vollstedt, Rezat, Kaiser and Presmeg2019, p. 87) and grouped phrases and lines of thought into themes and sub-themes to provide an understanding of their perspectives and the context (Krasniqi, Reference Krasniqi2024). Axial coding then sorted those open codes into our four structural levels and allowed us to embrace “abductive” reasoning, where theory and data are considered simultaneously (Gioia et al., Reference Gioia, Corley and Hamilton2013). Table 2 shows these codes. We present in the findings section meaningful phrases that best captured each variable. As Rousseau and House (Reference Rousseau, House, Cooper and Rousseau1994) highlight, context, parallels and discontinuities in behavior across levels create more realistic, though less tidy, research as the shift from “traditional organizational units to organizational activities creates the need to integrate micro and macro processes in the study of organizations” (p. 17). The larger themes captured the structural levels, while the sub-themes explore the key variables within each (Table 3).

Table 2 List of interviews used in coding

|

Name alias |

Gender |

Age |

Role in the organization |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Elena |

F |

50–60 |

Director |

|

Vasile |

M |

50–60 |

Director |

|

Daniel |

M |

40–50 |

Director |

|

Radu |

M |

40–50 |

Director |

|

Maria |

F |

50–60 |

Director |

|

Mihai |

M |

40–50 |

Director |

|

Stefan |

M |

50–60 |

Comisar chief |

|

Anatolie |

M |

30–40 |

Head of the local unit |

|

Ioana |

F |

40–50 |

Project manager |

|

Cristina |

F |

30–40 |

Temporary employee |

Table 3 Summary of Coding

|

Structure |

Strategy |

Process |

Rewards |

People |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Within partner organizations |

Internal hierarchy; Individual roles; Who represents? |

Mission; Alignment of refugee needs |

Communication; Decision Making; Dividing Labor |

Finding need; Better serving refugees |

Extra work; Emotional strain; Personnel time & cost |

|

Between partner organizations |

Knowing others’ missions |

Aligning resources; Changing Needs |

Coordinated approach; Holistic needs |

Improve response |

Previous relation; Camaraderie |

|

Within the newly created partnership |

Who led; Who initiated; Hierarchy; Meetings |

Why join?; Limit duplication |

Decision making; Information sharing |

Avoiding duplication; Dealing with changes |

Previous ties; Equality; Common empathy |

|

Between the partnership & external stakeholders |

Bureaucracy with state; Non-task force members |

More holistic needs approach |

Communication; Helping refugees as needs change |

Achieving goals; Feedback; Reputational benefits; Reaching more refugees |

Language skill; Feeling of accomplishment |

FINDINGS: The Structural Location of Tension

Here we address each of the four component sets of relationships. For each, we report the tensions reported, using a general framework of structure, strategy, process and people to organize each section (Galbraith, Reference Galbraith2002). We label respondents by sector; governmental organizations (GO), nongovernmental organizations (NGO) and private firms (PRIV).

Tensions Within Organizations: Knowing Themselves

Within participating organizations, structural complexities were reported as a difficulty. For example, “The Regional Police Transport Section … is structured within the General Inspectorate of the Romanian Police. … We are directly subordinated to the Inspectorate. We do not subordinate to the County Inspectorates.” (GO1) This structure left little room for flexibility especially since this was such an unusual arrangement for the National Police.

Respondents raised strategic issues around mission creep, “We eventually started scholarship programs for those who wanted to continue their studies in high school. Later, our activities expanded into environmental aspects, including tree planting, ecological actions, and so forth.” (GO4) Some reflected that the decision to work with the task force, or refugees generally, was less than strategic. “It wasn't a calculated decision; it was an impulse that we had and followed, and that's how the Ukraine project came about.” (NGO2) And, uncertainty reigned, “Initially, we didn't know. From one day to the next (NGO3).”

There was much discussion about decision-making within organizations vis-a-vis the task force. “To the extent that I could make decisions, I made them then and there; if not, I would come back.” (NGO4) Another commented, “Approvals were not necessary because it was conveyed to us from the start, and we acted in accordance with our internal orders.” (GO1) Others recognized structural limitations, “One person can't maintain contact with everyone.”(GO3).

There was discussion of “emotional moments” for staff, “seeing refugees just like us, with children, with elderly people in need. It overwhelmed their emotions most of the time.” (GO2) Another suggested work was difficult, “Under the pressure of the moment and with people arriving without anywhere to stay, without proper clothing, without food to eat.” (NGO2).

Respondents raised concerns about the additional workload which compounded their normal duties, “Working continuously for 12 h alongside the daily tasks that couldn't be neglected while managing this was a very big effort” (GO1) or, “in addition to our concrete tasks that we naturally had to take.” (PRIV1) Obviously, “the workload and the level of involvement were much higher because the problems were significant, numerous, and pressing.” (GO4) Others focused more on costs, “because, at least on weekends, overtime hours are paid differently.” (GO1).

Tensions Between Organizations: Recognizing Strengths, Needs and Hierarchy

Regarding work with other organizations, several respondents suggested formal and official partnering was more difficult, so instead, joint activities “were carried out mostly on a voluntary basis.” (GO1) They recognized each other’s limitations, “As we all know, or should know, the law allowed them to do much fewer things than it allowed us. They had procedures, a code of conduct, and so on. As private individuals, we didn't have these steps to take to implement something. It was much more complicated for them.” (GO4) But most felt overwhelmed by the complexity and needed help, “When you come with chemotherapy treatment and need continued support, it's quite challenging, especially considering that you're not a citizen. You have to redo all the paperwork; there had to be hospitalizations, and authorities had to be open to these situations.” (NGO2) Some complexities had to do with language, forcing them to find partners “who knew the Russian language better because there were also Ukrainians who spoke Russian.” (GO1).

Additional difficulties emerged, “later, as other NGOs arrived.” (NGO3) The biggest concern seemed to be the duplication of effort or beneficiaries taking advantage of NGO resources. “Initially, people were coming to both places, taking food packages from both places, and that was to the detriment of those we couldn't help because resources are limited.” (NGO2) We heard this often. “Everyone was offering services, but they were simply overlapping for individuals we were offering services to. So, they benefited from the same services from two different sides, and perhaps others were left out.” (NGO1).

While attempts were made to address this, they didn’t last. “A platform was actually built at that time, … to register every refugee arriving … and connect them based on their needs with a nonprofit organization. However, … the platform stopped working.” (NGO1) We learned the platform was designed at the national level and was not effective at the local level. As a result, they were forced to use their own networks. “When there were questions, we directed them to those whom we believed knew or were supposed to know to answer us.” (GO4) Some difficulties also arose, “When it came to international partners, there were communication barriers such as language and understanding.” (NGO2) As one respondent summarized, “If our goals align, of course, we collaborate. If we're not friends, we go on separate paths, we don't intersect.” (GO4).

Tensions Within the Partnership: Making Decisions and Navigating Uncharted Terrains

Respondents reported that they had worked together before, though informally. “It was somewhat a revival because they had this task force set up at the beginning of the pandemic. … and the group was reactivated.” (NGO5) Another commented, “Let's all pitch in, let's divide it so nobody ends up in burnout.” (PRIV1).

Respondents suggested this situation was complex because “there were many entities that do not fall under the Ministry of Internal Affairs and, implicitly, the Prefecture, but it was under the coordination of [the] County.” (GO1) This local governance structure differs from the Prefecture which represents national interests. They seemed to recognize this was a delicate balance, “There was a hierarchy because they represented the law, and of course, things could only happen with their agreement. They had a right of veto.” (GO4) This reveals another layer of complexity beyond local or national, to include hierarchical public entities compared to less formal, more flexible local NGOs.

They realized the need for control. “Of course, there was a hierarchy in the group because without hierarchy, there would have been anarchy.” (GO4) But they stressed this was not a command-and-control environment. “There were no decisions made and established from top to bottom because it was a horizontal collaboration.” (NGO5) This generated a lot of commentary. “As a non-governmental organization based on volunteering, you have the option to withdraw from an activity or a group at any time. An NGO's hand cannot be forced in any way because an NGO acts because it wants to, not because it must.” (GO4) They also recognized when their autonomy was paramount. “When we entered Ukrainian territory… that was our task. So, we managed that part.” (GO4) And generally, they suggested, “It wasn't a decision-making collaboration. … Decisions had to be made on the spot; you couldn't say, ‘Mrs. Prefect, may I do this thing?’ Because by then, the train had left.” (NGO5).

They spoke of meetings often, “There weren't many physical meetings because we didn't have time for that.” (NGO5) Regardless, “There were multiple meetings, and WhatsApp working groups” (NGO6) which were sometimes “Simply arranged on a day-to-day basis because a response was needed from the organizations we worked with at that time.” (NGO2).

As plans changed for one entity, for example the railroads, it created complications for task force members, “Due to the connections, there was a half-hour between trains. They came by train from [the East] and had to take the train to Budapest, and they didn't have time for us to bring them to the station and provide those food packs.” (GO1) Partners didn’t always receive information in a timely fashion, making more strategic planning difficult, “Discussions always revolved around urgent needs, not necessarily on planned things because the situation fluctuated from month to month, week to week. A very extensive plan couldn't be made.” (NGO2).

They spoke of frustrations when, “Other people representing different organizations or entities joined the group,” (GO3) increasing workload, “Later, other people joined the group … and the number of beneficiaries increased because we discovered more and more cases.” (GO4) While the task force helped reduce beneficiary “double dipping” for benefits, it did not solve it. And they sometimes still worked in isolation, “We were quite delimited in a way. Each one was doing their own activity.” (NGO1) Another reflected, “It wasn't all smooth sailing; we had contradictory discussions,” (GO4) but they felt this was normal.

Tensions Between the Partnership and External Beneficiaries: Changing Needs

The government presented some constraints. For example, “Refugee status allows you 90 days after which you either leave or submit your documents for immigrant status, then you become an immigrant and start looking for a job, sending your children to school, kindergarten.” (GO4) This proved difficult for NGOs working on behalf of their beneficiaries who tried to “collaborate with companies, try to find them a job, help them stay in that job.” (NGO2) Others spoke of tactical concerns that made providing assistance to refugees more difficult. “At the moment when we had to bring them from the farthest (train) platform, from platform 5, transport them with luggage to platform 1, distribute certain aids, and then take them back to the platform, it was an effort.” (GO1).

Respondents suggested they alienated well-meaning Romanians who wanted to help, “Some people were dissatisfied because they couldn't go and donate themselves.” (GO2) The task force had rules, and, “Organizations came … or even individuals who wanted to help and they were not used effectively.” (GO3) For example, many “Wanted to bring pots of stuffed cabbage” for the refugees, but this “Needed to be controlled. We couldn't give them food and then something bad might happen.” (GO1).

Communication issues seemed the biggest concern regarding beneficiaries. “Even though communication within the group was good, outside the group, there wasn't much communication. It was much more deficient. We even ended up overlapping services; essentially, offering the same services to the same people from two different entities.” (NGO2) This was often the case with donors and international NGOs. “We had previous difficult experiences with external partners who had certain expectations that were a bit challenging to fulfill because they didn't understand the situation on the ground.” (NGO2).

Finally, they mentioned evaluating their work, “Aligning the needs with the partners' expectations required some work, lots of explanations, many reports, and lots of photos and videos so that people could understand exactly what's happening with their money and see the actual need.” (NGO2) Others suggested it just wasn’t done at all.

Discussion

This case study illustrates the opportunity to re-conceptualize how scholars and practitioners think about tensions in CSSPs. The task force we studied exposed four levels of tension. Below we highlight our most interesting findings using the levels as a guide.

At the micro-level, our respondents found responding to the refugee crisis compelling but it was not a strategic decision per se (Bode et al., Reference Bode, Rogan and Singh2019). Acute crises tend to speed up or alter the decision-making process of potential respondents (Boin & t’Hart, Reference Boin, ‘t Hart and Rodríguez2018; Kapucu, Reference Kapucu2006a, Reference Kapucu2006b; Kruke & Olsen, Reference Kruke and Olsen2012). Relatedly, the acute nature of the crisis seemed to allow organizations to worry less about mission creep (Sedgwick, Reference Sedgwick2016) even though most of the CSSP had little previous experience with migration. These findings suggest that events characterized by acute need against a backdrop of charged emotions may reduce tensions by focusing on the task at hand.

Individual organizations seemed to differ in how they perceived tensions associated with representation. Government sector organizations reported more tension related to who would be their designated representative, while NGOs reported that they were always represented by their executive director. This is the first instance we found where a particular tension’s perceived impact changed based on the entity reporting. It is an important finding that justifies our conceptualization.

Our study reiterates the importance of prior knowledge of partner organizations and prior experience partnering as a potential source of tension. While our task force had not previously worked together, they did report positive previous knowledge of one another and relied on those experiences to align interests and capabilities quickly (Gillett et al., Reference Gillett, Loader, Doherty and Scott2019). This is consistent with literature suggesting prior negative experiences can be a significant source of tension (Gazley, Reference Gazley2017).

At the meso-level, our task force reported tension surrounding competition (Hahn & Pinske, Reference Hahn and Pinkse2014), as evidenced by participants’ ongoing concerns about duplicating services. If frequency is indicative of significance, this was the greatest tension at this level. Second, and consistent with within-organizational tensions, we again saw a difference in perception of a particular tension, based on sector. Representatives from the governmental sector seemed to accept bureaucracy as a necessary procedural hurdle for certain tasks, while NGO representatives accustomed to more flexible, flatter approaches were critical of bureaucracy.

At the neo-organizational level, we begin to see sensemaking in the CSSP as participants engage with the new independent identity. Sources of tension here related to power imbalances. Respondents spoke often of fairness and inclusiveness (Henry et al., Reference Henry, Rasche and Möllering2022) and worried about power. Members recognized the need for leadership to control the task force’s activities, even if they did not desire the associated hierarchy. Task force turnover did not prove to be an issue (Chlebna & Roche, Reference Rohe and Chlebna2022). But tensions did emerge as new members joined the task force, frustrating members by revisiting issues deemed settled. This is not something we anticipated, having only considered CSSP turnover in the traditional sense (Intindola et al., Reference Intindola, Pittz, Rogers and Weisinger2020).

Finally, at the extra-neo-organizational level, previous research highlighted the tension created by intractable or “wicked” problems (Churchman, Reference Churchman1967; Rittel, Reference Rittel and Webber1973). Haller et al. (Reference Haller, Rischke, Yanasmayan and Etlar Frederiksen2025) highlighted such issues with respect to homestays in Germany. Generally, this task force focused on pragmatic issues which made such grand challenge questions less salient. They did not perceive their role as “solving” the refugee crisis. Rather, their purpose was to ameliorate day-to-day issues. One such tension mentioned often was the unintended alienation of community members trying to help the refugees. In order to keep the services provided consistent and ensure the safety of food and materials provided to refugees, the task force had to limit some community volunteering. The task force’s recognition of this alienation is consistent with recent research on the topic of “spontaneous volunteers” (SVs), informal organizations and the difficulty inherent in integrating both into pre-existing structure and protocols (Carius et al., Reference Carius, Graw and Schultz2025; Domaradzka et al., Reference Domaradzka, Żbikowska and Domaradzka2025; Nowakowska et al., Reference Nowakowska, Duda, Ellena, Poli Martinelli, Szulawski and Pozzi2025). This is a particularly important finding in light of research suggesting that such unintended SV alienation, while tied to safety precautions, may have greater-reaching negative effects on refugees, particularly those ultimately settling in the area (see Barreto et al., Reference Barreto, Berbée, Gallegos Torres, Lange and Sommerfeld2022).

Tensions were also reported around conveying the impact of the task force (Benjamin et al., Reference Benjamin, Ebrahim and Gugerty2023), especially true vis-a-vis external funders. Task force members weighed the tensions associated with documenting their progress against actual direct service provision. This finding underscores the notion that while impact is difficult to measure for any single level or sector (Smith, Reference Smith and Smith1973); attempting to measure a CSSP’s impact is even more burdensome. Karakulak and Faul (Reference Karakulak and Faul2024) addressed this deeming refugee crises “one of the grand challenges of the twenty-first century” (p. 18), the authors propose a model that encourages CSSP partners to consider how their “refugee frames” (e.g., refugees as charity, customer or burden) affects the actions they take and the impact they create.

Taken together, our conceptualization of tensions at varying levels of a CSSP also ties into long-acknowledged conflict management literature. The overt recognition of conflict or tension may seem obvious at one level (within organizations or between two partners) but may not be detected or voiced at another level. Our work underscores the importance of both potential and realized tensions (Pondy, Reference Pondy1967). Beyond merely threatening the stability of a “unit,” conflict is “a key variable in the feedback loops that characterize organizational behavior” (p. 298). While Pondy illustrates his conflict model within a single organization, our findings multiply potential impacts by considering them at all four levels. Pondy (Reference Pondy1967) also recognized that the location of the conflict determines how the conflict may be addressed and whether it is functional or dysfunctional, a point we endorse.

Secondary to our conceptualization of tension levels, our work contributes to broader research on migration, refugees and humanitarian crises where findings across multiple settings align with ours. Research on the 2015 European Refugee Crisis highlighted barriers to partnering due to bureaucracy and accountability (Martin & Nolte, Reference Martin and Nolte2019), the need for different skills at different times (Kaltenbrunner & Reichel, Reference Kaltenbrunner and Reichel2018) and that spontaneous volunteers while helpful, often add complexities (Boersma et al., Reference Boersma, Kraiukhina, Larruina, Lehota and Nury2017; Simsa et al., Reference Simsa, Rameder, Aghamanoukjan and Totter2018). Similar findings have emerged from the current Ukrainian refugee crisis (Mikheieva & Kuznetsova, Reference Mikheieva and Kuznetsova2024). Gunasekara et al. (Reference Gunasekara, Eversole, Hiruy, Sendjaya and Breitbarth2022) found mindsets regarding refugee employment differed markedly across sectors. Information sharing and communication difficulties seem constant (Celik & Corbacioglu, Reference Celik and Corbacioglu2010; Comfort et al., Reference Comfort, Ko and Zagorecki2004; Kapucu, Reference Kapucu2006a, Reference Kapucu2006b). Collective decision-making and the role of power seem a perennial concern (Cosgrave, Reference Cosgrave1996; Kruke & Olsen, Reference Kruke and Olsen2012), as does representation (Curtis, Reference Curtis2018; Nolte et al., Reference Nolte, Martin and Boenigk2012), building trust (Stephenson, Reference Stephenson2005) and the importance of boundary spanners who bridge sectors (Kapucu, Reference Kapucu2006a, Reference Kapucu2006b).

Conclusions

This paper relies on interview data collected among participants on a cross-sectoral task force working to assist Ukrainian refugees with the goal of understanding more explicitly the different levels of a CSSP and the types of tension occurring at each level. Tension within a CSSP can now be viewed more granularly and addressed more effectively depending on where the tension emerged. Tensions highlighted around leadership, representation, trust, etc., and their resolutions may take place on different planes, within an organization, between two participating organizations, within the task force itself or between the task force and its external stakeholders.

Our paper also has practical implications. First, the organizational variables typically addressed in CSSP research can be found at different levels, often simultaneously; they just manifest differently. Second, mechanisms to resolve such tensions may be found at a different level than where the tension emerged. Leadership issues at the newly created task force might be addressed by selecting different organizational representatives. Communications from the task force to external beneficiaries might be better received coming from individual member organizations. As such, the most practical implication of our four-tiered model is in helping scholars and practitioners better apply existing research and best practices to the appropriate level of the CSSP.

We acknowledge the limitation that this task force was widely viewed positively internally and externally at national and international levels. We encourage future research to explore cases where tensions damaged a CSSP, consistent with calls to study failures and successes while building theory (Dahlin et al., Reference Dahlin, Chuang and Roulet2018). In addition, this task force, from creation to completion, lasted two years. With the light at the end of the tunnel, players seemed willing to put up with minor frustrations for such a noble cause. Regardless, our study demonstrates that tensions exist even in positively viewed partnerships.

The framework also highlights the complex ecosystem of IORs. Task forces themselves are rarely researched as distinct organizational entities and the relationship between task forces and beneficiaries receives even less attention. Each level should be considered distinctly, but we also need more research into the interactions among levels, for tension resolution and to better understand the interaction between tensions and differing perceptions of them. Might solutions at one level resolve tensions at another? We highlight this as an important direction for future research.

Funding

Partial financial support for travel was received by one author from Bucknell University. No additional funding was received to assist in the preparation of this manuscript. All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript. The study (and informed consent process) was approved by the Bucknell University Institutional Review Board.