It is now well established that our dietary choices significantly impact both human health and the environment(Reference Mambrini, Penzavecchia and Menichetti1). With the global incidences of chronic diseases and the scale of environmental emergency expected to increase dramatically over the next 25 years, addressing the underlying causes is urgently needed(Reference Lumsden, Jägermeyr and Ziska2). One of the main contributors to this scenario is the current food system, which considerably relies on animal protein-based products. These products generate substantially higher greenhouse gas emissions and place greater strain on natural resources, compared to plant protein-based foods(Reference Nijdam, Rood and Westhoek3). Plant protein-based products are foods made from plant sources, such as legume seeds, specifically designed to replace animal-based products and provide an alternative to consumers looking to reduce animal protein intake.

The EAT-Lancet Commission has highlighted the potential of a shift towards plant-based diets to promote both environmental sustainability and public health(Reference Willett, Rockström and Loken4). Numerous studies have shown that diets rich in whole grains, legume seeds, seeds and nuts, fruits and vegetables, are associated with reduced risk of various diseases such as cardiovascular diseases and hypercholesterolemia(Reference Wang, Zheng and Yang5,Reference Kahleova, Levin and Barnard6) . Reflecting this growing awareness, plant protein-based analogues have gained ground in the food market over the past decade(Reference Schulp, Ulug and Elise Stratton7). Up to 2020, over 6485 plant-based meat analogues had entered the global food market(Reference Boukid8). From a global market analysis conducted by Andreani G. et al., the market for plant-based meat analogues is projected to reach USD 33·99 billion by 2027(Reference Andreani, Sogari and Marti9). However, there is ongoing debate over whether plant protein-based analogues of meat, dairy and egg offer the same nutritional quality as their animal-based counterparts, due to the fact that animal products have a different nutritional quality from that of whole plant foods such as cereal grains and legume seeds(Reference Tso and Forde10). While animal protein products tend to have a consistent and predictable nutritional composition based on their source, whole plant ingredients such as legume seeds show considerable variability in their nutrient composition across species and geographical location(Reference Nolden and Forde11). This translates into increased challenges when formulating plant-protein based products with comparable protein content and nutritional quality to the animal equivalents(Reference Cole, Goeler-Slough and Cox12).

Despite these nutritional challenges, creating plant protein-based foods that resemble animal protein products is crucial for promoting a more sustainable food system(Reference McClements and Grossmann13). However, developing a plant protein-based product that closely replicates the taste, texture, and flavor of animal protein-based foods poses a significant technological hurdle among food scientists(Reference Andreani, Sogari and Marti9). Unfavorable sensory attributes – such as the beany and grassy flavors of certain legume seeds and their derivatives (e.g. tofu from soybeans) – often discourage consumer acceptance over animal products(Reference Onwezen, Bouwman and Reinders14). Due to the inherent compositional and structural differences between plant and animal products, many plant protein-based analogues are processed to closely mimic key attributes of animal products, such as the chewiness of meat or the creamy mouthfeel associated with dairy products(Reference Boukid8). Therefore, food processing of plant protein sources plays a crucial role in enhancing the texture and taste of the ingredients(Reference Onwezen, Bouwman and Reinders14,Reference Grossmann and McClements15) . Additionally, processing can also play an important role in improving the nutritional quality of plant proteins, and its impact will be discussed in more detail further.

Regardless of all the benefits of food processing, certain conditions can also lead to unwanted modifications of the proteins. Heat treatments are often used in the production of plant protein-based foods, either to guarantee safety or to remove compounds that limit the digestion and absorption of nutrients, known as antinutrients(Reference Adhikari, Schop and de Boer16–Reference Meade, Reid and Gerrard18), but excessive heat can also result in unwanted chemical reactions such as protein oxidation or Maillard reaction(Reference Kutzli, Weiss and Gibis19,Reference Poojary and Lund20) . These chemical modifications can result in lower digestibility, low bioavailability of amino acids and formation of pro-inflammatory compounds, so-called advanced glycation end products (AGEs), potentially contributing to the onset of inflammatory diseases(Reference Uribarri, Cai and Sandu21). However, the extent of these modifications in plant-based products remains unclear, as does whether they pose a significant risk to human health.

Considering the level of processing that plant protein-based foods have been subjected to, these products are classified as processed or ultra-processed foods (UPF) under the NOVA classification system(Reference Boukid8), which categorizes food products according to their degree of industrial processing and use of additives(Reference Monteiro, Cannon and Moubarac22). Several studies have reported associations between high UPF consumption and adverse health outcomes(Reference Sullivan, Appel and Anderson23,Reference Rauber, Campagnolo and Hoffman24) . However, the strength and causality of this association in relation to plant-based foods are the subject of ongoing debate within the scientific community(Reference Messina and Messina25,Reference Estévez, Arjona and Sánchez-Terrón26) . Emerging discussions highlight the need to account for potential confounding factors, such as lifestyle, cultural dietary differences, variability in food composition, and statistical assumptions, which may influence the association between UPFs, currently including plant protein-based analogues, and negative health effects(Reference Sanchez-Siles, Roman and Fogliano27,Reference Visioli, Del Rio and Fogliano28) . Furthermore, classifying plant-based foods as UPFs might confuse consumers and limit the transition towards more plant-based diets, while increasing the fear of processed foods.

Therefore, in this review we will focus on the relevance of processing plant proteins from legume seeds and the impact of different processes on their nutritional quality. Lastly, we will critically discuss the use of NOVA to classify plant-based products.

Plant protein nutritional quality: is it a concern?

Protein nutritional quality refers to how well a protein source is digested and its ability to supply sufficient amounts of all indispensable amino acids (IAA) needed to support human metabolism, in accordance with dietary recommendations(29). Plant proteins often have lower nutritional quality than animal proteins due to variations in digestibility and amino acid composition, such as limited lysine in cereals or methionine in legumes(Reference Hertzler, Lieblein-Boff and Weiler30). Unlike animal-based proteins, most plant sources are considered incomplete, as they lack adequate levels of all IAAs. Combining complementary plant proteins can help achieve a balanced amino acid profile(Reference Gorissen, Crombag and Senden31).

In addition, plant proteins are embedded in a complex structural matrix rich in starch and fiber, which can hinder digestion and nutrient accessibility(Reference Ogawa, Donlao and Thuengtung32). Furthermore, antinutrients such as protease inhibitors, phytic acid, and saponins further impair protein digestion(Reference Rousseau, Kyomugasho and Celus33–Reference Singh and Arora35). To address these challenges, food processing techniques can be applied to reduce antinutrient levels and modify the structural matrix, thereby enhancing nutrient absorption and improving protein digestibility(Reference Amin, Petersen and Malmberg36), as explained in more detail below.

Processing can influence protein digestibility of plant-based foods through four main pathways: (1) removal or inactivation of antinutrients, such as protease inhibitors(Reference King, Leong and Alpos37); (2) disruption of plant cell integrity by breaking or weakening plant cell wall structure(Reference Bhattarai, Dhital and Wu38); (3) alteration of protein structure and/or protein-carbohydrate or protein-polyphenol complexes(Reference Hsu, Vavak and Satterlee39); and (4) modification of amino acid side chains(Reference Kaur, Mao and Beniwal40). Among these, the inactivation or removal of antinutrients is highlighted as the main pathway for improving plant protein digestibility(Reference Sá, Moreno and Carciofi41). Additionally, processing can lower microbial contamination, contributing to overall food safety.

In the next section we briefly discuss the effect of common process conditions applied to improve the nutritional quality of plant proteins. Review studies have already comprehensively described the effect of different processing methods on the plant protein digestibility of legume seeds(Reference Sá, Moreno and Carciofi41–Reference Gu, Bk and Wu47)

Improving plant protein nutritional quality by processing

Various processing methods have been developed to ease the consumption of plant-based foods, as processing is expected to improve safety, shelf life, palatability, nutritional value, and protein utilization(Reference Drulyte and Orlien42,Reference Knorr and Watzke48) . The demand for convenience from consumers is also a motivation for developing processed plant-based foods that require no or minimal preparation before quick and easy consumption(Reference Knorr and Watzke48–Reference Poti, Mendez and Ng50).

Conventional house-hold processing methods, such as soaking and boiling, have been used to decrease the content of antinutrients in legume seeds(Reference Faizal, Ahmad and Yaacob51). More details on the effects of antinutrients can be found in reviews by Amin et al. (Reference Amin, Petersen and Malmberg36) and Manzanilla-Valdez et al(Reference Manzanilla-Valdez, Ma and Mondor52), but in short: phytic acid chelates minerals such as iron, zinc, and calcium, reducing their bioavailability; tannins form complexes with proteins and digestive enzymes, lowering digestibility; protease inhibitors inhibit enzymes like trypsin and chymotrypsin, impairing protein breakdown; lectins (hemagglutinins) primarily bind to intestinal epithelial cells, interfering with nutrient absorption; bitter-tasting saponins can disrupt micelle formation, reducing fat-soluble vitamin uptake and protein digestion; and prebiotic Raffinose Family Oligosaccharides (RFOs) may cause gastrointestinal discomfort such as bloating and, through accelerated transit, indirectly reduce protein and micronutrient absorption. Soaking generally serves as a precooking treatment for legumes, softening their texture, shortening cooking time, and partially removing antinutrients before further processing. Boiling is a process that involves both heat transfer and compounds leaching, which means it can remove some temperature-sensitive or water-soluble antinutrients such as protease inhibitors, RFOs, lectins, phytic acid, saponins, and tannins(Reference Drulyte and Orlien42). It has been reported by El-Adawy et al. that soaking decreased levels of tannins, hemagglutinins, trypsin inhibitors, and phytic acid by 68·7 %, 84·1 %, 29·7 %, and 21·1 %, respectively, in soybean flour(Reference El-Adawy, Rahma and El-Bedawy53). As reported by Shi et al. (Reference Shi, Arntfield and Nickerson54), boiling reduced the lectin by more than 93 % in Canadian pulses: peas, lentils, faba beans, chickpeas, and common beans. The reduction or elimination of lectin content during boiling may occur due to the breakdown of their structures into subunits or other, as yet unidentified, conformational changes(Reference Shi, Arntfield and Nickerson54). Other thermal processing methods, including autoclaving, extrusion, microwave heating, and roasting, can also reduce antinutrients through mechanisms similar to boiling(Reference Sá, Moreno and Carciofi41).

In addition to thermal processing, bioprocessing methods such as germination, fermentation, and enzymatic treatment of plant materials can be equally effective in reducing antinutrient levels(Reference Faizal, Ahmad and Yaacob51). Germination has been shown to decrease phytic acid levels by 18–21 % in lentil, cowpea, green gram, and chickpea(Reference Ghavidel and Prakash55), trypsin inhibitor activity by 31–100 % in jack bean, moth bean, and soybeans, and tannins by 50–60 % in pigeon pea, chickpea, black gram, and green gram(Reference Savelkoul, Van Der Poel and Tamminga56). Fermentation can reduce antinutrient levels through two main mechanisms: (a) microorganisms involved in the fermentation process produce enzymes that degrade antinutrients; and (b) they generate organic acids in plant-based foods, which enhance the activity of endogenous plant enzymes such as phytase and polyphenol oxidase(Reference Rousseau, Kyomugasho and Celus33). As reviewed by Das et al. (Reference Das, Sharma and Sarkar57), fermentation with Bacillus subtilis eliminated raffinose and stachyose in soaked and autoclaved soybeans, while fermentation with L. bulgaricus reduced phytic acid by 85·4 % in kidney bean, 77 % in soybean, and 69·3 % in mung bean. After fermentation with mixed lactic acid bacteria culture, a 21·7 % reduction of tannins and 25 % reduction of trypsin inhibitors occurred in yellow peas(Reference Ma, Boye and Hu58). Moreover, pure enzymes or enzyme isolates can be added to legumes directly to reduce antinutrients. For example, Çelem and Önal(Reference Çelem and Önal59) demonstrated that adding phytase to soymilk hydrolyzed 92·5–98 % of the phytate content. Similarly, an α-galactosidase isolate from L. plantarum reduced trypsin inhibitor activity, phytate, and tannins in soybeans by 50 %, 81·2 %, and 75·5 %, respectively(Reference Adeyemo and Onilude60).

Processing legumes into protein ingredients

The processing methods described above are applied mostly to the legume seeds, after which they can be consumed directly or further processed to make protein ingredients and final plant-based products. Most of the protein-rich plant-based foods available on the market are made with protein concentrates or isolates extracted from legumes and cereals(Reference Penna Franca, Duque-Estrada and Da Fonseca E Sá61).

The conventional method to extract proteins from legume seeds is a wet fractionation process, which is based on the solubilization of proteins at alkaline or acidic pH, followed by precipitation of the protein at the isoelectric point, resulting in either a protein concentrate (∼50–80 % purity) or a protein isolate (> 80 % purity)(Reference Huang, Zhang and Mujumdar62). Following this, the protein fraction is dried by e.g. spray drying. This production of protein concentrates or isolates by wet extraction induces changes in the protein structure, often resulting in partially denatured and aggregated proteins as a result of pH changes and drying conditions(Reference Verfaillie, Cho and Dwyre63,Reference Yang, Mocking-Bode and Van Den Hoek64) . In addition, wet fractionation reduces antinutrient levels in the protein concentrates/isolates, as many of these low-molecular-weight compounds are lost in the supernatant during the protein precipitation step due to their solubility(Reference Amin, Petersen and Malmberg36). Therefore, considering the high content of protein and the low content of antinutrients in the protein concentrate/isolate obtained by wet fractionation, the protein digestibility is expected to be improved. The extent to which protein digestibility improves in ingredients obtained through wet fractionation depends on several factors, including process conditions, the plant protein source, and the methods used to assess digestibility. More detailed information on protein fractionation and its effects on protein digestibility and antinutrients can be found in the following studies(Reference Amin, Petersen and Malmberg36,Reference Rivera Del Rio, Boom and Janssen45,Reference Manzanilla-Valdez, Ma and Mondor52,Reference Huang, Zhang and Mujumdar62,Reference Aldalur, Devnani, Ong and Galanakis65) .

One example of how wet fractionation can improve the nutritional quality of plant proteins was shown in the work of Krause et al. (Reference Krause, Sørensen and Petersen66), who investigated a faba bean protein isolate obtained through isoelectric precipitation as explained above. Compared to the raw faba beans (0·80–1·37 g/100 g), the isolate exhibited very low levels of phytic acid (< 0·4 g/100 g DM), thereby improving the mineral bioavailability(Reference Zehring, Walter and Quendt67). The isolate also contained low levels of protease inhibitors, contributing to improved in vitro protein digestibility. This was observed despite the relatively high content of condensed tannins, compounds known to potentially hinder protein digestion by forming enzyme-blocking complexes. These findings suggest that, under the tested conditions, the wet fractionation process was effective in enhancing the digestibility of proteins extracted from faba beans.

Despite the benefits of wet fractionation in terms of nutritional quality and food applications, this method uses a lot of energy and water(Reference Aldalur, Devnani, Ong and Galanakis65). More sustainable processes exist, such as dry fractionation, which separates particles based on their density(Reference Schutyser, Novoa and Wetterauw68). In this process, two main ingredients are produced: a starch-rich fraction and a protein-rich fraction. The latter is a protein concentrate containing a complex matrix of protein, starch, fibers, and antinutrients, all contributing to a lower protein nutritional quality in these ingredients compared to protein concentrates or isolates obtained by wet fractionation. In fact, Vogelsang-O’Dwyer et al. (Reference Vogelsang-O’Dwyer, Petersen and Joehnke69) reported that faba bean protein isolate produced by wet fractionation showed about 10 % higher degree of hydrolysis compared to faba bean protein concentrate, obtained by dry fractionation. This improvement was attributed to the effective removal of protease inhibitors from the faba bean seeds during wet fractionation, which enhances overall protein digestibility. Besides the removal of these antinutrients, some of the cell wall and starch were still present in the faba bean concentrate, which can also be a contributing factor to reduced protein digestibility. The study also made a life cycle assessment and found that dry fractionation showed a significantly lower environmental impact per kilogram of protein compared to wet extraction, mainly because milling and air classification required much less energy and water input than isoelectric precipitation. When compared to cow’s milk protein on a per-kilogram-protein basis, both faba bean ingredients have substantially lower potential environmental impacts across all indicators. Here we face a paradox in processing plant proteins, in which more sustainable processing does not produce an ingredient with high protein nutritional quality, and studies are relevant to understand where we can find an optimal balance between sustainability, nutritional quality and processing(Reference Duque-Estrada and Petersen70). Another study by Lie-Piang et al. (Reference Lie-Piang, Braconi and Boom71) also compared the environmental impact of wet and dry fractionation by evaluating the global warming potential per kilogram of protein, including cultivation and transportation. Yellow pea protein isolate produced by wet fractionation had a carbon footprint of approximately 5·3 kg CO2-eq/kg protein, whereas dry fractionation showed the lowest impact at 1·6 kg CO2-eq/kg. For lupin, wet fractionation resulted in a slightly higher footprint of 5·8 kg CO2-eq/kg protein compared to 1·3 kg CO2-eq/kg for dry fractionation, largely due to oil removal, increased water use, and the energy required for water evaporation.

Post-fractionation processing: strategies to enhance nutritional quality of plant protein ingredients

Further processing of e.g. protein isolates or protein concentrates can be done by texturizing plant proteins, either by low-moisture extrusion (LME), often named texturized vegetable proteins (TVPs), or by high-moisture extrusion (HME). Extrusion has been shown to reduce antinutrients, such as protease inhibitors, while improving protein digestibility – thereby offering a strategy to enhance the nutritional quality of plant protein concentrates that otherwise have a lower nutritional quality than the plant protein isolates produced by wet fractionation(Reference Sá, Moreno and Carciofi41,Reference Omosebi, Osundahunsi and Fagbemi72) .

In a study by Duque-Estrada et al. (Reference Duque-Estrada, Hardiman and Bøgebjerg Dam73), LME was used to produce TVPs by blending three sources of plant proteins, primarily composed of pea and faba bean protein concentrates obtained through dry fractionation. This process led to a reduction in trypsin inhibitor activity by more than 74 % compared to the unprocessed blends. For two of the TVPs, which contained over 79 % pea protein concentrate, in vitro protein digestibility improved around 20 % following extrusion. However, extrusion also negatively affected the profile of IAA, with a greater loss of sulfur-containing amino acids – methionine and cysteine – observed in TVPs with higher pea protein content. These losses are likely caused by protein oxidation or Maillard reactions occurring under the high temperatures used during extrusion(Reference Hülsebusch, Heyn and Amft74). TVPs are commonly used as direct meat alternatives, but they also offer potential for incorporation into other food products. Laugesen et al. (Reference Laugesen, Dethlefsen and Petersen75) explored one such application by enhancing the nutritional value of wheat buns through partial substitution of flour with TVPs. Replacing 35 % of the wheat flour led to a substantial increase in protein content—83 % —while maintaining acceptable sensory and baking qualities. The findings suggest that TVP fortification is a promising strategy for developing protein-rich bread suitable for food service settings and for individuals with elevated protein needs, such as older adults.

Other studies have also investigated the effect of extrusion conditions on plant protein digestibility, like, Fu et al. (Reference Fu, Li and Zhang76), evaluating how temperature and screw speed during LME affected in vitro protein digestibility of the TVPs produced using a mixture of soy protein isolate and concentrate, red pigment resulting from rice fermentation using Monascus sp. and water (ratios of 30:42:1:27). The results showed that the processing conditions have a significant impact on the resulting protein digestibility, depending on the extrusion conditions applied. Among the tested conditions (140–190°C and 24–40 rpm), the highest digestibility was achieved at 150 and 160°C and 30 rpm. The authors attributed this to a reduction in β-sheet structures at these temperatures, which led to more unfolded protein structures, making them more accessible to digestive enzymes. This highlights that generalizations across processing methods are difficult, as even small changes in processing conditions can lead to significant differences in the resulting (nutritional) quality.

De Boer et al. (Reference De Boer, Capuano and Kers77) looked at how temperature and moisture during HME affect protein quality in soy products. They tested soy protein concentrate and soy protein isolate, separately, at different temperatures (100–160°C) and moisture levels (50–70 %). No significant reduction (0–7 %) on the amino acid scores was observed in both samples for most of the conditions tested, except for soy protein isolate extruded at 120°C and 50 % moisture (13–19 %). In this case, the moisture content applied to produce soy protein extrudate showed a significant positive correlation with amino acid score. The authors explained that the higher moisture content during extrusion is likely to help protect amino acids by diluting reactive compounds like oxygen species and oxidation products. This reduces their ability to react with amino acids and also decreases protein–protein interactions in soy protein isolate-based extrudates, leading to better preservation of protein quality. The effect of moisture was also observed in the in vitro protein digestion, with a significant positive relationship between moisture content and degree of hydrolysis at 120°C. Meanwhile, there was no significant effect of heat treatments on protein digestibility in both extrudates. The study suggests that moisture content has a stronger influence than temperature on how tightly proteins are crosslinked during HME of soy proteins, which was also evident from the changes observed in the texture of the extruded products. On the other hand, lower processing moisture was reported to increase the mechanical shear forces on soy protein, enlarging its surface area and enhancing interactions with digestive enzymes(Reference Du, Tu and Liu78). Overall, these results highlight that the type of proteins and preparation before extrusion might have a greater impact on the nutritional quality than the actual processing conditions.

The nutritional quality can also be changed by incorporating the plant protein concentrate (and/or isolate) into food formulations such as pasta or bread, as they undergo further processing steps, such as extrusion and boiling (pasta) or baking (bread)(Reference Hoehnel, Bez and Amarowicz79,Reference Hoehnel, Bez and Petersen80) . In a study by Hoehnel et al. (Reference Hoehnel, Bez and Amarowicz79), a high-protein hybrid pasta (HPHP) made by partially replacing wheat semolina with protein-rich ingredients from buckwheat, faba bean, and lupin was evaluated. The buckwheat and faba bean protein concentrates were produced by dry fractionation and were therefore expected to contain antinutrients, unlike the lupin protein isolate, which was produced by wet fractionation. Compared to regular wheat pasta, HPHP showed a more favorable macronutrient profile, particularly due to the substitution of starch with non-wheat protein(Reference Hoehnel, Bez and Amarowicz79). In terms of protein quality, the HPHP not only showed an improved profile of IAA, with lysine reaching 87 % of the WHO recommended level (v. 57 % in wheat semolina pasta), and tryptophan reaching 140 %, but also demonstrated superior protein quality in vivo, reflected in a 55·6 % higher nitrogen utilization rate and a significantly greater protein efficiency ratio (2·13 g/g in HPHP v. 1·37 g/g in wheat semolina pasta), indicating better alignment with amino acid requirements for growth. Regarding antinutrients, cooking HPHP reduced by 83 % vicine/convicine, and by 73 % trypsin inhibitor activity, with remaining levels not adversely affecting the nutritional value. Another study examined the nutritional value of a high-protein hybrid bread (HPHB) made by partially replacing wheat flour with protein-rich ingredients from faba bean, carob, and gluten(Reference Hoehnel, Bez and Petersen80). Compared to regular wheat bread, HPHB showed a more favorable macronutrient profile, a richer amino acid composition—particularly higher lysine—and significantly improved protein quality indicators, including a 69 % increase in nitrogen utilization and a higher protein efficiency ratio. In vitro and in vivo digestibility tests revealed that HPHB proteins were more readily broken down, likely due to better accessibility of amino acids targeted by digestive enzymes. Despite concerns about antinutrients in legumes, the formulation maintained low levels of trypsin inhibitors and demonstrated high antioxidant potential linked to phenolic content. Overall, according to the authors, these two studies support HPHP and HPHB as nutritionally superior alternatives to their traditional wheat-based counterparts, particularly in terms of enhancing protein intake and quality in predominantly plant-based diets. However, it is important to note that the extent to which in vitro findings translate to in vivo conditions remains uncertain, given the fundamental differences between the two systems. In vitro models lack many of the complex physiological processes present in vivo, such as dynamic gastric acid secretion, variable gastric emptying, and secretion and activity of digestive enzymes(Reference Menard, Lesmes and Shani-Levi81).

Besides extrusion, another process that is efficient in improving protein digestibility is fermentation, because it has the ability to decrease the levels of antinutrients and can pre-digest the proteins. In one of our previous works(Reference Thulesen, Duque-Estrada and Zhang82), we evaluated the effect of tempeh fermentation on faba bean in vitro protein digestion, amino acid composition, and trypsin inhibitor activity. To evaluate the effect of fermentation conditions, two tempeh samples were produced under different fermentation conditions, with one fermented for a shorter time at a lower temperature and the other for a longer time at a higher temperature. After fermentation, the activity of trypsin inhibitor activity was reduced by more than 60 % in both tempeh samples. Overall, the levels of IAA did not differ between the tempeh samples or when compared to the raw faba beans. The amount of free amino acids in both tempeh samples was higher than in the raw material, showing that fermentation pre-hydrolyses (or pre-digests) the proteins due to the presence of proteases released by microorganisms during fermentation. Surprisingly, the reduction in trypsin inhibitor activity did not lead to improved in vitro protein digestibility during the intestinal phase, even though this would be expected, as trypsin inhibitors are known to impair trypsin activity at this stage of digestion. Here, it was argued that protein aggregation might have counteracted the positive effect of the reduction of trypsin inhibitor activity. Overall, in vitro protein digestibility improved under both fermentation conditions compared to raw faba beans.

As previously mentioned, processing improves plant-based protein digestibility primarily through four pathways, with the reduction of antinutrients being the most significant. For instance, protein digestibility in soaked, sprouted, pressure cooked, and roasted pulses has been negatively correlated with trypsin inhibitor activity(Reference Kamalasundari, Babu and Umamaheswari83). In addition to antinutrient reduction, processing can enhance protein digestibility by increasing cell wall permeability, thereby facilitating protease access to intracellular proteins. Zahir et al. (Reference Zahir, Fogliano and Capuano84) reported that the process of combining fermentation and germination with heat treatment creates a loosely packed intracellular environment in soybean, which enhances protein digestibility. Structural alterations also play a role; Sun et al. (Reference Sun, Ohanenye and Ahmed85) reported that microwave treatment caused a 5 % decrease in β-sheet content and a 5 % increase in random coil structures, which enhanced protein susceptibility to proteolysis and thereby improved digestibility. It is important to note, however, that not all processing methods enhance protein digestibility. For example, high intensity ultrasonication induced a decrease (∼3·6 %) in protein digestibility of faba bean protein isolates by changing protein structure, more specifically, by increasing β-sheet, β-turn, α-helix, and intra-molecular aggregates and decreasing inter-molecular aggregates(Reference Martínez-Velasco, Lobato-Calleros and Hernández-Rodríguez86). Compared with raw faba bean, a 4·2 % decrease in protein digestibility was reported in cooked faba bean (soaked at room temperature for 2 h and cooked at 120°C for 20 min) by Carbonaro et al. (Reference Carbonaro, Cappelloni and Nicoli87), who attributed this decrease to the formation of protein aggregation. The authors explained that protein aggregation may hide the protease cleavage sites, modifying amino acid side chains that hinder protease recognition sites, and forming protein-polyphenol complexes that resist enzymatic hydrolysis. Therefore, it is important to adopt a nuanced view of processing, acknowledging not only the diversity of techniques but also their potential differing impacts on protein digestibility.

Plant protein-based analogues: formulations and processing

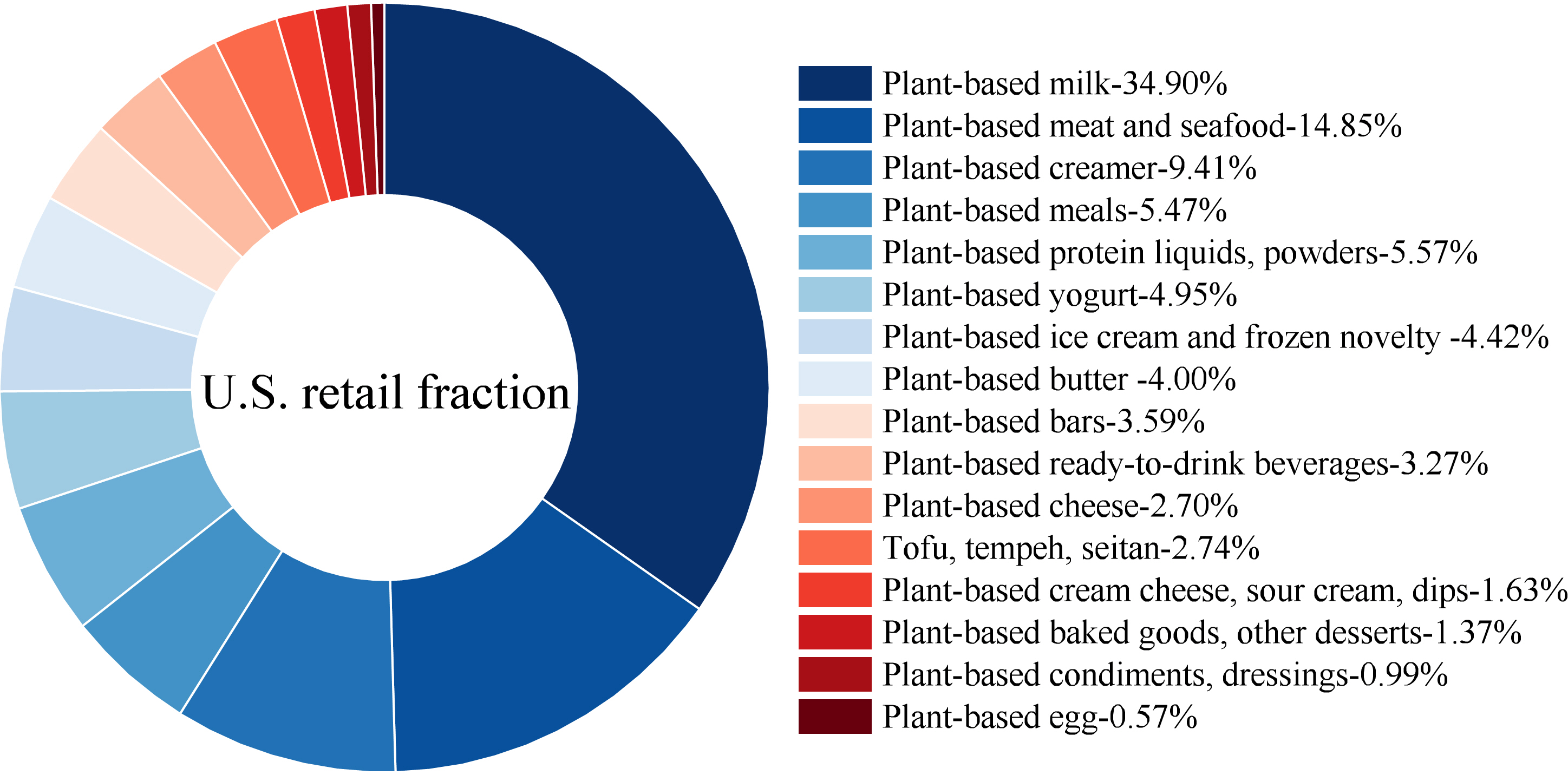

Numerous plant-based foods are designed to mimic animal-based products, and their categories and U.S. retail fractions are shown in Figure 1. The market has expanded from 6 categories in 2018 to over 20 categories today, including plant-based milk, meat, seafood, eggs, yogurt, cheese, butter, creamers, protein powders, baked goods, and ready-to-drink beverages(89).

Figure 1 U.S. retail fraction of plant-based food categories. Data from The Good Food Institute(88).

Plant-based milk alternatives account for 35 % of the plant-based food market in U.S., representing the largest share among all categories (Figure 1). Plant-based milk alternatives are colloidal suspensions or emulsions, which consist of plant proteins that are extracted from cereals, legume seeds, nuts, oilseeds or pseudocereals combined with stabilizers, hydrocolloids, and emulsifiers(Reference Reyes-Jurado, Soto-Reyes and Dávila-Rodríguez90). The processing steps in producing plant-based milk alternatives include raw material extraction, removing coarse particles or excess fat, formulation, homogenization, heat treatment, nutrient fortification, and packaging(Reference Reyes-Jurado, Soto-Reyes and Dávila-Rodríguez90). The extent of processing and number of ingredients can vary greatly, but common to many are high-temperature processing steps to pasteurize the products(Reference Silva, Silva and Ribeiro91). Compared with dairy milk, plant-based milk alternatives generally contain lower levels of protein, IAAs, fat, calcium, and vitamin C, which contributes to the perception of their inferior nutritional value(Reference Pingali, Boiteau and Choudhry92,Reference Vashisht, Sharma and Awasti93) . A recent study found that plant-based milk alternatives (PBMAs) undergo extensive processing to mimic cow’s milk, which significantly alters their nutritional composition(Reference Pucci, Akıllıoğlu and Bevilacqua94). In particular, ultra-high temperature (UHT) treatment promotes the formation of Maillard reaction products, including potentially harmful compounds like acrylamide and α-dicarbonyls, that were detected in higher levels in PBMAs compared to UHT-treated cow’s milk. Additionally, PBMAs were found in this study to generally contain less protein and fewer IAAs, resulting in lower overall nutritional quality. However, plant-based milk alternatives contain some unique bioactive compounds, such as isoflavones, phenolic compounds, phytosterols, and β-glucan, which have demonstrated specific health benefits(Reference Aydar, Tutuncu and Ozcelik95). For example, consumption of soybean milk has been shown to reduce LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) as well as blood-pressure(Reference Biscotti, Del Bo’ and Carvalho96). Similarly, a daily intake of 0·75 liters of oat milk over five weeks significantly lowered serum total cholesterol and LDL-C levels compared to a control drink (rice milk)(Reference Önning, Wallmark and Persson97). In addition, fortification with external nutrients, including vitamins, and minerals, is commonly applied to improve nutritional profiles. Processing methods as well as formulations of plant-based milk continue to evolve; therefore, it is too early to conclude which type of milk offers the most favorable health benefits.

In recent years, the food industry has also developed other plant-based alternatives to dairy products, such as creams, yogurts and cheeses, whose nutritional value varies depending on the raw materials used and the specific processing routes applied. A study conducted by Moshtaghian et al. (Reference Moshtaghian, Hallström and Bianchi98) investigated the nutritional profile of 222 plant-based dairy alternatives, including milk, yoghurt, cheese, cream, ice cream, and fat spread, and reported that plant-based dairy alternatives had higher fiber content but lower protein content than their corresponding dairy products. Zeinatulina et al. (Reference Zeinatulina, Tanilas and Ehala-Aleksejev99) compared 25 commercial plant-based yoghurts (lupin, soybean, oat, coconut) and reported that only one oat product exhibited high-quality protein with a Protein Digestibility-Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS) > 0·9. This was attributed to the inclusion of additional plant protein sources, which provided a complete amino acid profile. Most products had low mineral content, further limited by phytates, although calcium-fortified products showed satisfactory bioavailability.

Another category of plant protein-based products is meat analogues, which are produced to mimic the texture and flavor of certain types of animal meat. The main material of meat analogues is plant protein ingredients, which are mixed with water, carbohydrates, and lipids in a certain proportion and then extruded by an extruder under high temperature(Reference Sun, Ge and He100). Generally, protein mixtures would be supplemented with additives, such as vitamins, minerals, colors, flavoring, binders, and preservatives, before extrusion(Reference McClements and Grossmann13). To mimic the specific meat type, the choice of ingredients and their proportions, type and parameters of the extruder are adjusted accordingly. Similar to plant-based milk alternatives, meat analogues generally contain lower levels of protein, IAAs, and certain vitamins and minerals compared to animal meat. However, they can also provide beneficial dietary fibers, which are absent in animal-based products. The digestibility and bioavailability of plant-based meat are generally lower than those of animal meat(Reference Xie, Cai and Zhao101,Reference Xie, Cai and Huang102) . As reviewed by Shan et al. (Reference Shan, Teng and Chen103), both formulation and processing conditions affect the digestibility of plant-based meat. The digestibility of plant-based meat is largely influenced by the protein material. Although plant protein-based foods, such as meat analogues, are typically rich in fibers, low in cholesterol and saturated fat, factors linked to a lower risk of development of chronic diseases, they are often processed with added salts, sugars, and low-quality fats, which can compromise their overall nutritional quality(Reference Nolden and Forde11,Reference Penna Franca, Duque-Estrada and Da Fonseca E Sá61) .

Processing or formulation: a critical distinction in evaluating plant-based UPFs

In the current discussion about UPFs, the terms processing and formulation are often used interchangeably, yet they refer to distinct aspects of food production. Processing involves the physical, chemical, or biological transformation of raw ingredients—ranging from techniques like milling, boiling, pasteurization, and extrusion, to protein hydrolysis and protein or starch modifications. Formulation, on the other hand, refers to the combination of ingredients used to create a final product, including additives, flavorings, and isolated nutrients.

The NOVA classification system, widely used to categorize foods by their degree of processing, tends to conflate these two concepts(Reference Shaghaghian, McClements and Khalesi104). For example, NOVA Category 2 includes vegetable oils without distinguishing between e.g. cold-pressed virgin olive oil and refined hexane-extracted olive oil, despite their differing processing methods and nutritional profile(Reference Monteiro, Cannon and Levy105). Similarly, whole-grain flour and refined wheat flour—where the nutrient-dense germ and bran are removed—are treated as equivalent in terms of processing level. This lack of nuance suggests that NOVA’s definition of UPFs is more reflective of ingredient complexity than of actual processing techniques. The term ultra-processed itself implies a focus on processing, which can be misleading when the classification seems primarily to be based on formulation.

We believe, though, that this distinction is critical, as highlighted in a recent commentary by food scientists who argue that NOVA fails to accurately reflect the level or nature of processing(Reference Petrus, Do Amaral Sobral and Tadini106). Instead, it categorizes foods based on the number and type of ingredients, often ignoring well-established food science principles. The authors caution that this approach may unfairly stigmatize processed foods, including those that are nutritionally beneficial when appropriately designed(Reference Petrus, Do Amaral Sobral and Tadini106). We believe that understanding the difference between processing and formulation is essential when evaluating the nutritional quality of plant-based foods, as both factors can influence outcomes in distinct and meaningful ways. This is also highlighted by Sadler et al. (Reference Sadler, Grassby and Hart107), who argue that food processing classification systems lack scientific consensus and rely on subjective, socio-cultural concepts rather than objective, measurable criteria. Furthermore, the authors claim most systems do not include quantitative measures but instead imply a correlation between processing and nutrition, highlighting the need for clearer definitions of ‘whole food,’ the role of the food matrix in healthy diets, and more robust debate around food additive risk assessment(Reference Sadler, Grassby and Hart107).

This oversimplification has significant implications for plant-based products, many of which are automatically categorized as UPFs and thus perceived as unhealthy or undesirable(Reference Monteiro, Cannon and Levy105). However, such blanket categorization fails to account for the nutritional improvements that can result from specific processing methods. For instance, as we have discussed in the preceding paragraph, extrusion to produce TVPs can enhance protein digestibility and reduce antinutrient levels.

In general, we believe that we have been able to show that processing can play a beneficial role in improving the nutritional quality of plant-based foods. These effects are particularly relevant in the context of plant-based diets, which may rely on processed ingredients to achieve adequate nutrient intake and protein quality. However, processing can also have negative consequences—such as the loss of micronutrients, disruption of the food matrix, or the inclusion of additives that may impact health—especially when driven by cosmetic or commercial goals rather than nutritional intent. A balanced understanding of processing must therefore consider both its potential to enhance and to compromise nutritional outcomes.

The Restructure project has designed a randomized controlled feeding trial that hypothesizes that texture-driven differences in eating rate can moderate energy intake, even when foods are equally ultra-processed, suggesting that physical properties of food play a key role in satiety(Reference Lasschuijt, Heuven and Van Bruinessen108). This aligns with findings from a recent study showing that meals containing TVPs led to lower energy intake compared to meat or non-texturized legumes, despite similar macronutrient profiles(Reference Martin, Dynesen and Petersen109). Together, these studies challenge the assumption that all processed foods are nutritionally inferior and highlight the potential of food texture as a tool to influence satiety and energy intake.

Given the complexity of how processing and formulation interact to shape nutritional outcomes, there is a clear need for more nuanced classification systems and evidence-based dietary guidance, as also suggested by ‘The Task Force on Food Processing for Nutrition, Diet and Health’ established by the International Union of Food Science and Technology (IUFoST)(Reference Ahrné, Chen and Henry110). Public health messaging that broadly discourages UPFs may inadvertently stigmatize nutritionally beneficial plant-based products. Instead, we believe that a more refined approach should consider the type and purpose of processing, the nutrient profile of the final product, and its role in supporting dietary adequacy. Recognizing the potential of well-processed plant-based foods can help shift the narrative from avoidance to informed selection.

Conclusion

The processing of plant protein-based foods plays a complex role in determining the nutritional and functional qualities of the final product. A central challenge lies in designing processing methods that achieve an optimal balance between environmental sustainability, nutritional adequacy, and desirable sensory properties of plant protein-based foods, particularly those derived from legume seeds. Processing techniques such as fermentation and extrusion show promise for improving the nutritional quality of plant protein ingredients, whether whole legume seeds or concentrates, while supporting sustainability targets such as reducing energy use.

This review highlights the need for a novel food classification framework that integrates processing methods and formulation complexity of food products, thereby encouraging the use of processing technologies that yield nutritionally adequate plant protein-based foods. Future research should focus on evaluating the beneficial and adverse effects of sustainable processing on the nutritional characteristics of plant protein-based products to guide the development of nutritious plant-based foods.

Author contributions

All authors contributed equally to the writing and editing of the manuscript.

Financial support

We would like to acknowledge the project ‘Dansk Bælg’ funded by Green Demonstration and Development Programme (GUDP) under The Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Fisheries of Denmark, Grant number 34009-23-2191, and the project ‘Immune SEEDstem’ funded by Plant2Food, a Novo Nordisk Foundation Sponsored Initiative, Grant number NNF22SA0081019, for their financial support.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.