The WHO has stated that between 2015 and 2050 the world’s population of over 60s will nearly double from 12 to 22%(1). This is even more so in Scotland’s whose demographic structure is moving to a higher proportion of people in older age. There are now over 1 million people over the age of 65 in Scotland which has increased by 22.5% since 2011.(2) This number is continuing to grow with estimates that the number of people of pension age in Scotland will increase by 20.6% from mid 2020 to mid 2045(3). Data released by National Records of Scotland(2) revealed that the number of people aged ˃65 years across Scotland increased by >250,000 over a 20-year period. While an increase in average age was evident in 32 Scottish Council areas, the four largest cities in Scotland had the lowest proportion of people aged over 65 years while Argyll and Bute having the highest proportion with 27.2% aged over 65 years(2). With an ageing population, malnutrition in later life is an increasing Public Health challenge particularly in remote rural communities where timely access to healthcare can be more challenging due to geographical distance. Consequently, a new approach is needed. This review paper will aim to look at the issues with current methods of dietary monitoring particularly in older adults, it will present the benefits and barriers of using to monitor food intake. It will discuss how a photo food monitoring app was developed to address the current issues with technology and how it was tested with older adults living in community and care settings.

Health implications in later life

Older adults are particularly vulnerable to nutritional problems in later life.. Malnutrition is strongly associated with frailty, and it contributes to poorer quality of life, functional decline and deteriorating health(Reference Fávaro-Moreira, Krausch-Hofmann and Matthys4,Reference Wei, Nyunt and Gao5) . These can lead to malnutrition which remains one of the most common challenges among older adults in the UK. It is estimated that about 1 in 10 people over the age of 65 years are malnourished or are at risk of malnutrition which rose to 1 in 4 aged over 60 years during the COVID 19 pandemic(6). The prevalence of severe malnutrition is reported to be as high as 55% in hospitalised older adults(Reference Norman, Pichard and Lochs7) and up to 45% in those in residential care(6), while over one third of community-dwelling older adults suffer from milder malnutrition, nutrition risk and nutritional deficiencies(6). However, it is estimated that about 70% of undernutrition in the UK is unrecognised(Reference Schenker8) suggesting the problem may be more prevalent than previously thought. Malnutrition can be both a cause and effect of health conditions with many health conditions common in ageing leading to malnutrition. For example, dementia can mean that the individual may forget to eat or drink, have altered food preferences, or have difficulties swallowing certain foods and liquids(6). According to the NHS, common signs of malnutrition are unintentional weight loss, low body weight, a lack of interest in eating and drinking, fatigue, weakness and slow recovery time. This is a problem as malnutrition leads to poorer health and wellbeing in the longer term. Malnutrition related to disease is estimated to cost the NHS more than £23.5 billion per year in both health and social care costs(Reference Stratton, Smith and Gabe9). It is about two to three times more expensive to treat someone who is malnourished compared with someone who is not(Reference Elia10) with health and social costs attributed to malnourishment, estimated at £7408 per person. Therefore, targeting malnutrition at both community or clinical care level is crucial to improve healthy ageing and wellbeing in later life. Early detection prior to the need for NHS treatment and signposting to support is a prevention strategy that could solve this problem.

Malnutrition in older adults is commonly identified via the Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST)(Reference Elia10) administered by a dietician and results in a risk score. There are set criteria for when an individual should be given extra nutritional support such as a BMI of less than 18.5 kg/m2 or unintentional weight loss greater than 10% within the last 3–6 months. People can even become malnourished if they do not eat enough for 2–5 days(6). The high prevalence and negative consequences of malnutrition in later life outlined above suggests that early detection of malnutrition risk and prevention methods within older adults needs to change.

Dietary monitoring

It is estimated about 8 out of 10 people in Great Britain pay attention to what they are eating and drinking(12). Food monitoring and tracking can be undertaken using a variety of methods. Traditional methods include food records, FFQs and 24-h recall. Food records track all food, drinks and supplements consumed within a specific timeframe. For food records, intake should be weighed out and measured but in practice intake is generally estimated by the participant. The FFQ measures intake over a set period which is usually a longer period than a food record. The questionnaire asks how frequently a person consumes specific items over set periods of time. A 24-hour recall approach is usually an interview in which it is asked of the individual what they have consumed over the previous 24 hours and allows for prompting and probing questions to clarify and increase accuracy, particularly with older adults(Reference Campbell and Dodds13). Multiple measurement should be taken on different days to ensure variety and accuracy. Even though these three methods provide helpful and useful information, they are not always accurate and have various limitations. They rely on self-reported estimations given by the individual completing it which can often be inaccurate, specifically under-reporting(Reference Ravelli and Schoeller14), forgetting items(Reference Ravelli and Schoeller14) or be affected by socially desirable responding(Reference Hebert, Clemow and Pbert15). Diet diaries and food records are often complex requiring interpretation by a dietician, and if one uses it to monitor one’s own diet it does not provide support with making positive changes(Reference Ortega, Pérez-Rodrigo and López-Sobaler16). When measuring malnutrition specifically, where individuals are classed as medium to high risk on the MUST, it is recommended to document food and drink intake for 3-days, but again such written food diaries are inaccurate due to recording error and socially desirable responding(Reference Ortega, Pérez-Rodrigo and López-Sobaler16).

As outlined above, a new approach to dietary recording is needed as current malnutrition screening for older adults in the community or care is either non-existent or irregular and can be inaccurate when based on food diaries and recall.

Use of technology to monitor diet

In 2024, it was estimated that 98% of those aged over 16 owned a smartphone(17) ranging from 98% aged 16–34 and 82% aged 65 years and above(18). It was estimated in 2023 that the average user spent about 3 hours and 50 minutes per day(19) on their Smartphone with 98% of all users using apps(Reference Wurmser20). It is difficult to estimate the number of apps available that support users to monitor their diet and reach their goals, due to the extensiveness of the market but this is notably a growing industry(21). Some of the most popular apps out there are MyFitnessPal with 28% of users and the second most popular was Bodyfast Intermittent Fasting dropping to 7% of the market(22). Worldwide over 347 million people have downloaded an app to monitor their diet with 217 million users downloading a free app and over 140 million paying for an app. When examining using technology to monitor food intake in the UK, a YouGov study found that 30% of adults used an app or device to track their diet and/or weight(23). The reason behind the popularity may be due to advances in artificial intelligence particularly the use of machine learning technology. These advances allow apps to tailor content to the individual, providing personalised information based on preferences and goals. Computerised tailored education has a positive impact on dietary monitoring in the general population(Reference Kroeze, Werkman and Brug24). Automated food classification is an accelerating field of artificial intelligence research that uses a computer source to identify different foods from an image. Using existing nutrition databases this means that it is possible to store detailed nutritional data from photographs of food consumed. Next, machine learning techniques can be applied to correlate dietary intake with important individual differences such as food preferences, physical symptoms and, importantly, malnutrition risk. This means that certain foods could be linked with symptoms of conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome and other digestive symptoms like reflux and heartburn. This method has shown to be effective in other conditions such as sepsis(Reference Lukaszewski, Yates and Jackson25) and Diabetes(Reference Bell, Laparra and Kousik26). These techniques can also consider portion size and regularity of food intake, which is crucial to monitor in older people, particularly among those with cognitive impairment, who may forget to eat. Using automated food classification could link food intake to preferences and/or symptoms, fullness and energy levels quickly and accurately to identify foods no longer preferred, relating to symptoms, or changes in diet providing information to decrease malnutrition risk. Linking food intake to preferences and/or symptoms could be used to quickly and accurately identify potential risks, providing users with information to help monitor diet and decrease malnutrition risk. Further, in the aftermath of the pandemic, older adults are the fastest growing group adopting digital technology particularly to maintain family and social connections and there is a strong call to empower older adults to use technology to bridge potential social and digital divides which impact on health inequalities(Reference Seifert, Cotten and Xie27,Reference Hill, Betts and Gardner28) . This makes, the use of technology in supporting the health and wellbeing of older people a timely intervention. The capacity of digital technology to facilitate social interaction and reduce social isolation, as shown during the recent pandemic, can also be incorporated into AI tools to enhance their usability and extend their functionality.

Using technology to measure diet could help to promote positive behaviour change whilst reducing the problems associated with current methods. It could help reduce measurement error and support users into making positive life choices by gaining a greater understanding of their diet. With a growing number of the population now having access to a screen, there are many benefits to using an app. It has been found that using an app to monitor diet has increased motivation to change diet, choosing more healthier foods, has increased users’ ability and confidence to set and achieve diet-related goals, and has increased knowledge about food choices(Reference West, Belvedere and Andreasen29). Using a tool which also incorporates using photographs to record food intake rather than an online or written diary have been found to be the preferred option(Reference Martin, Han and Coulon30) in free living adults. Comparing energy intake from photograph to weighed food records was shown to be similar in nutritional estimations, however this was in a sample of nutrition students(Reference Wang, Kogashiwa and Ohta31) and has not yet been successfully replicated in other populations(Reference Kikunaga, Tin and Ishibashi32). Using technology has also been beneficial to record the timing of food intake, but not all apps(Reference Gioia, Vlasac and Babazadeh33) allow the user to change the time of recording food intake if this was not entered concurrently with when they were they were eating.

Current issues with apps

Similarly to traditional methods using technology through an app to record nutritional intake comes with its own limitations that may affect the accuracy of the information it is providing. Some of these limitations are outlined below:

Accuracy: Apps tend to wrongly estimate the total energy intake compared to written methods. One study by Tosi and colleagues(Reference Tosi, Radice and Carioni34) compared five nutritional apps with a 3-day food diary. They found that the apps underestimated total energy intake with lipid intake underestimated more than that of carbohydrates and proteins, which were still underestimated. It was estimated that these inaccuracies equated to about 700 calories per week which will have a resultant effect on weight loss in the long term as users may then be consuming more calories than they think. One suggestion for the reason behind these underestimations was the difference in the food composition databases each of the apps used as these databases allocated calorie content differently to foods, which differed per country where the apps were designed and used. Estimating portion size is another issue when it comes to measuring nutritional intake with one study finding 49% of the errors were due to not being able to estimate the portion correctly(Reference Beasley, Riley and Jean-Mary35). However, it was found that for the majority of apps(Reference Franco, Fallaize and Lovegrove36), portion estimation was only textual where the user was responsible for entering data and it did not use photos to support the user with data entry, thus incorporating photo evidence could provide a more accurate estimate of portion size and calorie content and could solve this issue.

Use of photographs to decipher foods: There are many issues when using photos to estimate nutritional intake. The quality of the photo has been shown to have an impact on nutritional estimation when compared to weighed food intake(Reference Kikunaga, Tin and Ishibashi32,Reference Vasiloglou, van der Horst and Stathopoulou37) . Food recognition is also an issue where the app could mis-recognise one food for another, giving nutritional values for the wrong item or not taking into account additives such as condiments or supplements such as thickeners(Reference Ho, Chiu and Kao38) which may be added to foods particularly in older adults. Very few apps account for what was actually eaten, focusing rather on just what was on the plate, so they may overestimate calorie intake, especially in populations who are high risk for undereating and malnutrition(Reference Norman, Haß and Pirlich39). To solve this, apps need to incorporate recognising what has been eaten from a plate in comparison to what was originally on the plate at the start of the meal and calculate intake.

Measuring health outcomes in relation to intake: There are not many apps that measure health outcomes related to diet or age and those that do focus mainly on allergies and intolerances which vary in quality(Reference Mandracchia, Llauradó and Tarro40). One review(Reference Ferrara, Kim and Lin41) of 7 diet apps, from 3 experts, found that they did not track the effect of mood or stress on dietary intake meaning that in their data there is no estimation of how social or mental health may affect eating patterns. This was seen as a limitation to the app as it would not support the user in tracking their health and identifying how to eat around any physical or mental health issues that may be affected.

Creating eating disorders: As well as issues with accuracy and underestimating nutritional intake, using an app to monitor diet does carry the potential risk of highlighting and leading to issues around eating. One study(Reference Hahn, Hazzard and Loth42) looking at younger adults has shown that using an app that is dietary-focussed has led to a greater prevalence of disordered weight-control behaviours such as fasting and purging and that more research is needed into harm reduction associated with using an app to monitor diet to be able to roll out these types of intervention safely.

Development of a tool for older adults

By combining automated food recognition with machine learning predictions of symptoms, a tool was developed to support dietary intake and related symptoms in older adults living in care settings(Reference Connelly, Swingler, Rodriguez-Sanchez and Whittaker43). The development of the tool offered individual advice to users with limited detailed input from the user themselves, i.e. they would simply need to input the presence of any symptoms when these occur from a list of common symptoms. Using a tool such as this could reduce the risk of error that is found in food diaries and increase adherence to monitoring which can be an issue with recording nutritional intake. It could help the user to take control of their own health and would also support the element of self-learning.

A nutritional assessment tool was co-developed and tested by key stakeholders and older adults living in both care homes and the community(Reference Connelly, Swingler, Rodriguez-Sanchez and Whittaker43). A brief overview of the development and testing process are as follows.

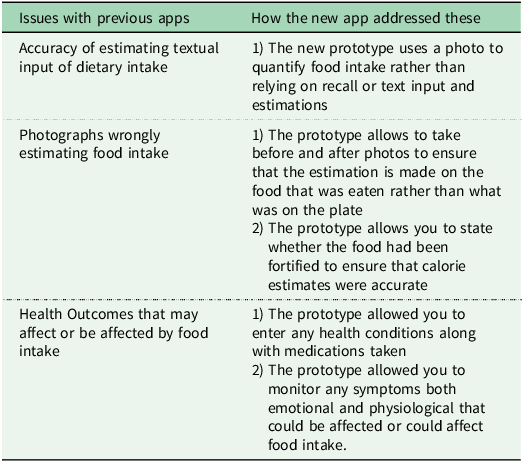

To minimise the issues and inaccuracies found with previous written and technology-based methods the first step was to create an advisory group with key stakeholders to develop ideas and identify features that would be key for a food recognition tool in older adults whilst addressing the current issues with dietary monitoring. The advisory group was made up with six key stakeholders (older adults, care home staff, app developers and a dietician) to design, test and improve the protype. Key features in response to current monitoring issues for the protype were discussed and priority was assessed. Discussion around the need for a food recognition model i.e., associated food database, was had and key features of it were noted. The advisory group helped the app designers and researchers to develop a prototype based on these issues and the issues found in previous studies which incorporated the following (A summary is available in Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of issues with previous apps and how the new prototype addresses these

Accuracy: As apps(Reference Tosi, Radice and Carioni34) tend to wrongly estimate the total energy intake compared to written methods, the current tool used an existing photo database as the food recognition model whilst building its own personalised database to enhance accuracy and to allow for enhanced food tracking. Once a photo was taken there was the option to click a correct food button or click circles around the food which allowed the user to overwrite the system if it had incorrectly identified a food. It supported the user to take the photo well, giving information on how to take the photo and distance to the plate, which helped to decipher plate size and therefore portion size. It prompted the user to use the app if they had missing meals but also prompted them to take an ‘after’ photo of the plate to account for any food still left on the plate. The app allowed the user to enter photos retrospectively and time stamp these in case making time to enter this information was a challenge at mealtimes, such as in busy care homes where staff were the users.

Measuring health outcomes in relation to intake: The app allowed creation of user profiles that allowed the app to store information in relation to the health of the user. It allowed for manual entry of current health conditions, but also symptoms that may be experienced that could be related to food intake such as gastrointestinal symptoms but also ratings of fullness and mood. This enabled the app to link symptoms and mood back to food photos to specific foods on plates. With frequent use, the app would learn which foods identified from photos related to which symptoms.

Creating eating issues: Due to the population the app was designed for, older adults, malnutrition and undereating were key to monitor. The app allowed for centralised storage so that an external user such as a dietician or care staff could take the photos, evaluate those who were higher risk through each user’s personal profile and only monitor those residents with the highest needs. The app would also give the care home, or interested parties, information on the resident’s eating patterns and symptoms.

The app was then refined and tested by the advisory group in free living conditions over a week. They were asked to fill out a short survey on their use of the app which found that the app monitored a good range of symptoms specific to the target group. However, some suggestions for additional symptoms were thirst, confusion and anxiety. They also reported that when the app connected well with the food recognition model (the online food database) it was easy to use but some had connection issues to the internet. The majority said that they did not feel any key features were missing but that when testing with older adults they will be able to highlight site-specific features.

Testing the app in older adults in care settings

The prototype was tested in three care homes with eight staff members and in one care home with six residents, two of which were younger adults with learning disabilities. Due to the cognitive ability of residents in three of the care homes, staff were recruited as residents would not be able to use the app; therefore, the staff members used it themselves. Following two weeks of testing in the care homes, semi-structured interviews with staff and residents were used to identify; 1) the pros and cons of using the app in their care home; 2) how it can be adapted to enhance its usability. The results from these were as follows:

1) The pros and cons of using the app in their care home:

Overall, both staff and residents enjoyed using the tool, with staff saying they would also like to use it to monitor their own diet. They said that it recognised the majority of foods well and once they were used to the app found it easy to change if foods were not correctly identified. Residents who were capable liked monitoring their own food intake and due to spending more time with the app used the features more accurately. All users said it was easy to pick up and that they learned how to use it quickly.

All the care home staff and residents reported difficulties in using the app when the care home Wi-Fi was poor. They reported slow upload, that the tool would freeze, or that they had difficulty clicking on the foods on the screen. This then led to slower identification of foods and a slow search for foods that were not identified and therefore the need for features that would make this faster. Staff did not use the delayed upload feature, and when asked, they reported that they were worried that if they did not upload immediately, they would not be able to upload photos and ratings later due to a change of shift or being given another role or task within the home’s busy shift pattern. A resident who was using the tool revealed that they did not have these issues because they just saved the photo to upload later when their Wi-Fi connection was stronger. Further, choking was identified as a major concern to across all the care homes that participated and many of the residents were on a pureed diet. The tool struggled to identify the pureed photos with some care homes even using moulds shaped like the food itself, consequently, they identified the need for better puree recognition or a way around this issue. Finally, when photos were taken of plates, the food recognition function of the tool sometimes identified the design patterns on the plate as foods. However, the more the tool was used the less this became a problem as users worked out how to delete the circle around the patterned part that was identified as a food, and the more it was used the less it would identify the pattern due to machine learning.

2) How it can be adapted to enhance its usability:

Staff wanted to add a measure of swallowing to the tool which would link to food intake and the International Dysphagia Diet Standardisation Initiative (IDDSI)(44). The current version did not link a swallowing feature, but this feature could encourage care homes to change the texture of the food if the app recognised the resident was having difficulty swallowing certain foods. Across all homes it was reported that there was the need for an enhanced resident profile, rather than the name function in the tool which takes them straight to the diary. They wanted to be able to upload a photo of each resident to click instead of a name, which takes them direct to a resident profile. This profile would incorporate relevant information about the resident such as weight, changes in weight, issues with previous foods such as stomach problems or swallowing, risky foods and allergies, IDDSI(44) and MUST Malnutrition score(11), co-morbidities, medications that may affect diet, and a category for food monitoring of high risk, medium risk, or low risk. Having the MUST malnutrition risk score assessed via the tool and keeping track of their IDDSI score was a high priority for care staff. This would support staff, particularly new staff who are less familiar with a resident, in ensuring the correct food is given or provide a warning signal when a picture is taken to highlight risky foods for that resident. A key concern for care home staff using the tool was the time it would take to take the photo making it challenging to deliver the meal to a resident that was still hot. Some homes had 80 residents and would not be able to monitor everyone on top of their other duties. Upon further discussion, a traffic light system was suggested that would categorise individuals into Green – does not need regular monitoring, Amber – needs monitoring but is not majorly concerning, Red – needs monitoring and may need observation or support with eating due to key issues such as swallowing or choking concerns. This would help reduce the time spent using the tool as they could prioritise residents who needed it most whilst eliminating the need for measurement in those who did not need it at all. An ‘empty plate button’ was suggested to quicken up the process so a second photo was not needed, a ‘half-finished button’ was also suggested but it was highlighted that they then would not know what parts of the meal were eaten so this might lead to an inaccurate estimation of nutritional intake. Creating a care home-specific database with pre-existing photos based on their current menus was identified to speed up usage and learning of the tool with the staff only needing to take an ‘after’ photo after selecting the pre-loaded ‘before’ photo from the limited menu. Another suggestion to quicken the process was to work with the care homes to build their menu into the tool.

Monitoring in community

Even though the app was developed for care home settings it was initially tested and evaluated in older adults living in urban and rural community settings.

Urban settings

A total of 10 community dwelling older adults over the age of 65 tested the app for two weeks and gave feedback on usability and future feature development. Nine of the ten older adults completed the two-week study. One had trouble with download and decided to not participate further in the study. Key feedback was positive with eight participants wanting to continue using the tool on a regular basis. Similar to the care home users, community users identified Wi-Fi and connectivity issues which resulted in problems with initial food recognition particularly of similar looking foods or obscure food. These were rectified with delayed photo upload and manual food identification entry with future recognition from the machine learning component to the app.

Rural settings

A pilot testing focus group was run in the remote location of Helmsdale, Highlands, Scotland. This involved two members of the development team presenting the app and testing it with a group of older adults living in rural community settings. The group was made up of 11 older women. From the group it was found that around half of the women used technology generally including online shopping, messaging, google searching and Facebook. They revealed that with living in a remote area during COVID 19, using technology was essential to keep in touch with their families and friends. There were many key influencers of nutrition and dietary intake identified in this group. Use of the app or the way they would like to use the app differed to from those living in urban communities or those in care homes. Those who were living alone revealed that making a healthy home-cooked meal for them alone was off-putting so they often chose convenience meals or processed foods. If they could use the app to meal share with other older adults in the surrounding area they felt this would be helpful. They mentioned that food waste was an issue and they wanted to minimise any waste so using the app to meal share would minimise this. The rural town where this focus group was run offered community initiatives that involved food and nutrition. There was a food shed that residents could go to which held food from the community garden in addition to donated food. However, although residents had access to the shed, it was revealed that many older adults avoided using this as they did not want to be perceived as poor or to take food from someone who may need it more than them, mentioning mums with young children and those with lower incomes. A lunch club was run once a week in the village. This was specifically for older adults and provided a meal and a social meet-up for older residents of the area. There were also organised group trips to the bigger towns where there were supermarkets. Access to food (availability and cost), health and seasonality were also issues raised which needed to be taken account of if the app was to be useful in this setting. All of these would be advertised on the app and create a social aspect to nutritional monitoring and food sharing. Other barriers to nutrition included: Local shops (expensive, does not stock healthy foods, poor quality, full of preservatives); Transport – the bus that could take to bigger shops is not suitable for those with poor mobility, price of fuel; Staff need for a referral to see a dietician, home carers are not monitoring what is being eaten, local public transport.Unlike the previous users the app was tested with, for this rural group, enhancing the social elements would be important and this could include lift sharing, food shopping sharing and sharing meals and recipes.

Conclusion

Using technology to monitor diet has been shown to be useful in older adults in care and community settings. There are many features of technology which can help support dietary monitoring but the priority of different features varied depending on the type of user. It was found in urban and care settings, users liked using a tool to help monitor their nutritional intake and symptom recording but in rural settings it was more for food security, waste minimisation and food sharing. Technology still has a long way to go in terms of food nutritional detection accuracy but is becoming more popular than traditional methods in all age groups. Further enhancement of existing tools and testing these in different settings is needed to ensure the accuracy of food recognition and converting into accurate nutritional values as well as the feasibility of incorporating the different functions highlighted by key user groups.

Acknowledgements

The authors would also like to acknowledge the fellow members of their research team who contributed to the collection of the data, Professor Kevin Swingler and Dr Nidia Rodriguez-Sanchez. The authors acknowledge the artificial intelligence company specialising in food recognition and nutrition analysis LogMeal (AIGecko Technologies SL, Artificial Intelligence and Deep Learning Food Division) for the use of its database. The authors would like to acknowledge and thank all advisory group members and tester participants.

Authors contributions

Authors contributed equally.

Financial support

This research was funded by a UK Research and Innovation Healthy Ageing Catalyst grant (ES/X006271/1), an Economic and Social Research Council – Stirling Social Science Impact Acceleration Account institutional block award to the University of Stirling, and a specific exploratory – Impact Acceleration Account and routes to commercialisation grant to JC and ACW (STI-23/24-P0001). The funders had no role in the study’s design; the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; the writing of the manuscript; or the decision to publish the results.

Competing interests

None declared