In the UK, approximately 64,000 individuals are living with an ileostomy(Reference Rolls, de Fries Jensen and Mthombeni1). Such surgery is typically indicated by refractory inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) or malignancy resulting in diversion or removal of all or part of an individual’s large intestine; the ileum is then externalised onto the abdominal wall, allowing for diversion of egesta into a disposable pouch(Reference Hill2). Those living with an ileostomy lack endogenous sources of nutrients produced in the colon (i.e., vitamin K and short-chain fatty acids)(Reference Michońska, Polak-Szczybyło and Sokal3) and the absorbative capacities of the large intestine(Reference Fulham4), therefore increasing risk of dehydration owing to increased fluid losses and excretion of electrolytes(Reference Rowe and Schiller5). Such physiological challenges are likely compounded by post-operative dietary changes and avoidance of foods associated with blockage or ileostomy-related symptoms (e.g., odour, flatulence)(Reference Burch6), subjecting people living with an ileostomy to sub-optimal nutrition and reduced quality of life (QoL). Despite these dietary and nutrition-related challenges, clinical evidence for dietary management of ileostomy is limited and there currently no consensus dietary guidelines for people living with an ileostomy(Reference Mitchell, England and Atkinson7), instead dietary advice is based on clinical experience and anecdotal reports(Reference Mitchell, Herbert and England8).

This review aimed to explore the dietary patterns of people living with an ileostomy, identifying common food restriction practises and exploring their impact on nutritional status and diet related QoL, before considering current solutions for improving dietary management and overall health.

Dietary patterns of people living with an ileostomy

Newly formed ileostomy

To support dietary adjustment post-operatively, people living with an ileostomy are often given advice by a dietitian, stoma care nurse or surgeon during their surgical admission(Reference Mitchell, England and Atkinson7). Guidelines generally recommend a low-fibre diet for the first 8-weeks post-operatively, with the aim of minimising unpleasant symptoms (e.g., stomal blockages, flatulence, odour)(Reference Fulham4,Reference Cronin9–Reference McCartney, Markwell and Rauch-Pucher11) . Adherence to such advice may lead to a substantial decline in fibre intake, particularly from fruits and vegetables. Evidence from a postoperative cohort of people living with an ileostomy demonstrates this risk clearly; a significant reduction in fruit and vegetable consumption was reported 20-days post-surgery, with 30% consuming more than two portions per day pre-operatively compared to 0% post-operatively (P < 0.05)(Reference Vasilopoulos, Makrigianni and Polikandrioti12).

Patterns of dietary restriction and food avoidance result in a net reduction in total energy intake (158 kcal/day or 8.4% reduction reported, P < 0.05)(Reference Migdanis, Koukoulis and Mamaloudis13). This, compounded by increased metabolic demands associated with surgical recovery, often contributes to energy deficits, weight loss(Reference Migdanis, Koukoulis and Mamaloudis13,Reference Mohil, Narayan and Sreenivas14) and an increased risk of malnutrition(Reference Vasilopoulos, Makrigianni and Polikandrioti12), which – in gastrointestinal (GI) surgical patients – is associated with slower recovery, increased hospital stays, higher costs, mortality and readmission rates(Reference Mosquera, Koutlas and Edwards15). Improving nutritional management for those with a newly formed ileostomy may help to lessen additional pressure on health services. Administration of effective and timely dietary intervention(s) could enhance surgical recovery and minimise long-term nutritional deficiencies.

Established ileostomy

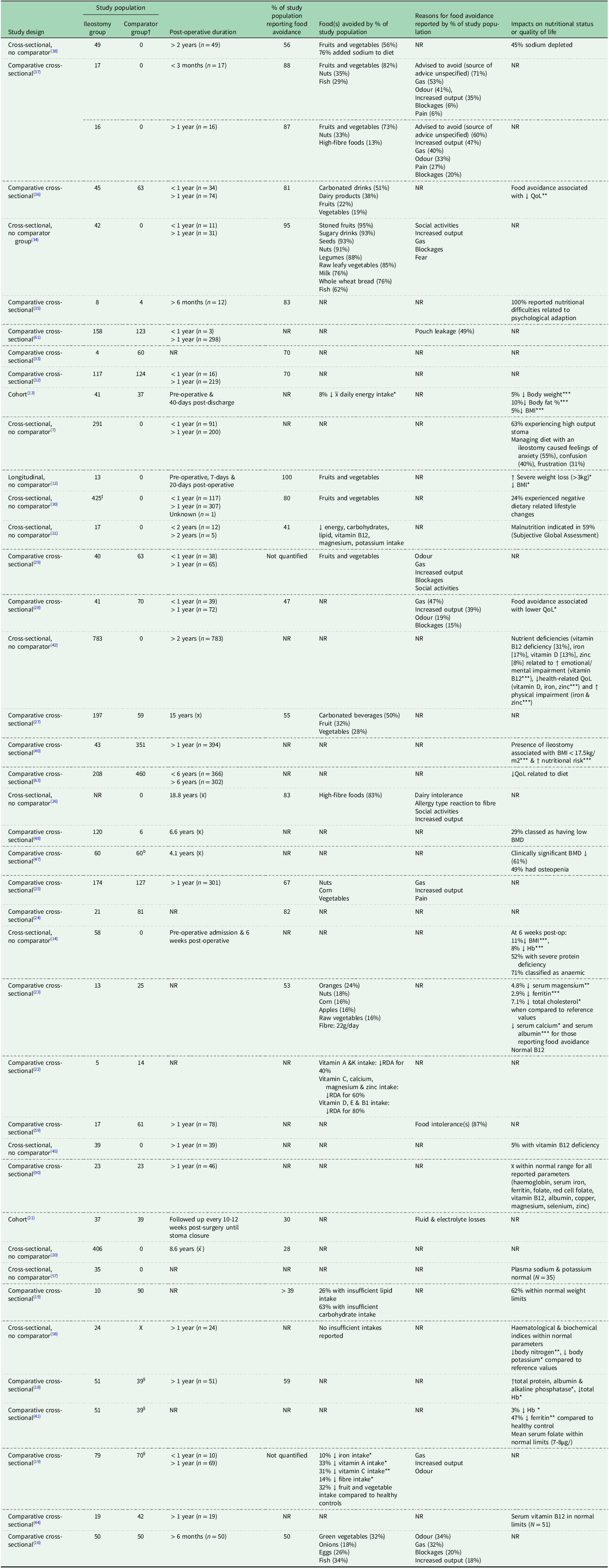

Following the first 8 weeks post-surgery, people living with an ileostomy should be encouraged to gradually increase fibre intake(Reference Cronin9), allowing for a return to a healthier balanced diet(Reference Burch6). This does not appear to be reflected in the dietary intake of those living with an ileostomy long term with numerous studies (as summarised in Table 1) reporting that dietary adjustments persist for months and years post-surgery(Reference Gazzard, Saunders and Dawson16–Reference Rud, Brantlov and Quist38). Restriction and avoidance of fruits, vegetables and foods high in fibre being the most common(Reference Gazzard, Saunders and Dawson16,Reference Bingham, Cummings and McNeil17,Reference Giunchi, Cacciaguerra and Borlotti19,Reference Estívariz, Luo and Umeakunne22,Reference de Oliveira, Boroni Moreira and Pereira Netto29,Reference Beeken, Haviland and Taylor30,Reference Drozd, Veissetes and Sancisi34,Reference Alharbi, Ahmad and Alhedaithy36–Reference Rud, Brantlov and Quist38) . One study compared the dietary intake of individuals 6-10 weeks post-operative to those living with an ileostomy for 12+ months, reporting that daily fibre intake remained unchanged over time (12g/day versus 11g/day respectively, P = 0.063). Further, a significant reduction in daily fruit and vegetable consumption was observed in those with a new versus well-established ileostomy (2.7 portions/day, 1.3 portions/day respectively; P = 0.002) suggesting continuation of the low-fibre diet and limited reintroduction of foods(Reference England, Mitchell and Atkinson37).

Table 1. Observational studies reporting dietary patterns of people living with an ileostomy and outcomes for nutritional status or quality of life (n = 40)

Abbreviations: NR, not recorded; QoL, quality of life; BMI, body mass index; BMD, bone mineral density; LBM, lean body mass; Hb, haemoglobin; RDA, recommended daily amount.

†Unless otherwise specified ‘comparator group’ denotes participants with other stoma type(s) or bowel conditions.

‡Any stoma, type not specified.

§Healthy control group.

*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Clinical guidance suggests soft drinks and dairy products should be consumed in moderate amounts(Reference Cronin9), which is reflected in long-term dietary patterns whereby carbonated and/or sugary beverages are also avoided by people living with an ileostomy(Reference Davidson27,Reference Drozd, Veissetes and Sancisi34,Reference Alharbi, Ahmad and Alhedaithy36,Reference England, Mitchell and Atkinson37) and to a lesser extent, milk and dairy products(Reference Gazzard, Saunders and Dawson16,Reference Estívariz, Luo and Umeakunne22,Reference Drozd, Veissetes and Sancisi34,Reference Alharbi, Ahmad and Alhedaithy36) . Lower average intakes of lipids and fat-soluble vitamins are commonly reported(Reference Michońska, Polak-Szczybyło and Sokal3,Reference Giunchi, Cacciaguerra and Borlotti19,Reference Estívariz, Luo and Umeakunne22,Reference Almendingen, Fausa and Høstmark23,Reference de Oliveira, Boroni Moreira and Pereira Netto29) and to a reduced degree, minerals (potassium, calcium, magnesium, zinc)(Reference Estívariz, Luo and Umeakunne22,Reference de Oliveira, Mendez and Pereira Netto28,Reference Moraes, Melo and Araújo31,Reference England, Mitchell and Atkinson37) and B vitamins(Reference Estívariz, Luo and Umeakunne22,Reference de Oliveira, Boroni Moreira and Pereira Netto29,Reference Moraes, Melo and Araújo31) .

Overall, dietary restriction and avoidance of a range of foods and drinks are predominant in people living with an ileostomy, regardless of time elapsed since surgery. Limitation of phytochemical-rich foods, such as fruits and vegetables, is of particular concern, given the breadth of epidemiological and clinical studies suggesting the health benefits associated with higher intakes of such foods (e.g., anti-inflammatory, cardio- and cancer-protective effects)(Reference Yang and Ling39). Evidence for the link between phytochemical intake and the onset of chronic diseases in people living with an ileostomy is lacking.

Sub-optimal nutrition and ileostomy

People living with an ileostomy may have suboptimal nutrition due to the reduced absorbative capacity resulting from removal of the colon(Reference Michońska, Polak-Szczybyło and Sokal3–Reference Rowe and Schiller5). Combining this with restrictive dietary behaviours, it is likely that nutritional deficiencies could develop as a result. Indeed, presence of an ileostomy has been associated with increased nutritional risk (OR 3.36 [CI; 1.17-9.70], P = 0.03)(Reference Jang, Yu and Lim40). Studies reporting nutrition-related measures in people living with an ileostomy are summarised in Table 1. Concerns regarding nutritional deficiency in people living with an ileostomy are most commonly in relation to vitamin B12, fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E and K) and electrolyte imbalances(Reference Michońska, Polak-Szczybyło and Sokal3). There is also evidence pointing toward the prevalence of iron deficiency in ileostomy cohorts(Reference Kennedy, Lee and Clareridge18,Reference Almendingen, Fausa and Høstmark23,Reference Kennedy, Callender and Truelove41,Reference Schiergens, Hoffmann and Schobel42) , however, this could be associated with the underlying disease necessitating the surgery (i.e., IBD)(Reference Kennedy, Callender and Truelove41), rather than dietary restriction or reduced absorption.

Vitamin B12 is absorbed in the terminal ileum and a consequence of the ileostomy surgery absorption is likely to be adversely affected(Reference Mantle43), however a paucity of studies has provided no consensus on vitamin B12 status in people living with an ileostomy (as outlined in Table 1). This lack of consistency could be explained in part by methodological variations. For example, earlier studies measuring absorption of vitamin B12(Reference Kennedy, Callender and Truelove41) or serum levels(Reference Kelley, Branon and Phillips44,Reference Jayaprakash, Creed and Stewart45) report no or low levels of B12 deficiency in people living with an ileostomy. In contrast, when a cohort of people living with an ileostomy (n = 783) were asked to report diagnosis of nutritional deficiencies, 31% reported suffering from vitamin B12 deficiency(Reference Schiergens, Hoffmann and Schobel42), which is quite concerning, considering this figure is approximately double the estimated prevalence of deficiency in the general population(Reference Shipton and Thachil46). Those with short bowel syndrome were found to be significantly more likely to self-report vitamin B12 deficiency (P < 0.001)(Reference Schiergens, Hoffmann and Schobel42), indicating that low B12 status in people living with an ileostomy is likely due to reduced absorbative capacity. However, the fundamental limitations of self-reported data should be noted; further studies utilising biochemical parameters and dietary intake data are needed to confirm the prevalence and cause(s) of such nutritional deficiency in people living with an ileostomy.

Diminished bone mineral density (BMD) has also been highlighted as a nutrition-related difficulty associated with living with an ileostomy. In a case-control study, nearly half (49.1%) of people living with an ileostomy (n = 59) were classed as having osteopenia following a DEXA scan, and a third of participants (33.9%) displayed BMD scores lower than expected for age(Reference Ng, Pither and Wootton47); these results are mirrored by others(Reference Gupta, Wu, Moore and Shen48). No significant differences in BMD were observed for those who had undergone small bowel resection and those who had not(Reference Ng, Pither and Wootton47). This could imply that alterations to the GI tract are not responsible for lowered BMD status in people living with an ileostomy. Instead, perhaps it is due to dietary restriction, ongoing inflammation(Reference Epsley, Tadros and Farid49) or prolonged steroid use and associated vitamin D deficiency(Reference Skversky, Kumar and Abramowitz50), which is particularly common for IBD in the lead up to ileostomy surgery(Reference Nguyen, Elnahas and Jackson51). In a cohort of those who had undergone ileostomy surgery, a negative correlation between food avoidance and lowered serum calcium (P = 0.03, correlation coefficient not reported) was observed(Reference Almendingen, Fausa and Høstmark23). Although serum calcium is not used as a biomarker for calcium intake, lowered calcium levels may be indicative of low vitamin D status and poor BMD. Without adequate replacement from other sources, prolonged dietary restriction of milk and dairy products(Reference Gazzard, Saunders and Dawson16,Reference Estívariz, Luo and Umeakunne22,Reference Drozd, Veissetes and Sancisi34,Reference Alharbi, Ahmad and Alhedaithy36) , could further increase people living with an ileostomy’ risk of poor bone health in the longer-term.

People living with an ileostomy can be prone to electrolyte imbalances and dehydration because of losses through [increased] stoma output(Reference Burch10). High-output stomas (HOS) – generally defined as daily output greater than 1500ml(Reference Nightingale52) – are prevalent in people living with an ileostomy during the first weeks following surgery(Reference Arenas Villafranca, López-Rodríguez and Abilés53) and is the most common reason for post-surgical hospital readmission(Reference Brady, Scott and Grieveson54–Reference Plonkowski, Allison and Philipson56). Whilst early studies report no electrolyte imbalances in those living with an ileostomy long term(Reference Kelley, Branon and Phillips44,Reference Svaninger, Nordgren and Palselius57,Reference Cooper, Laughland and Gunning58) , more recent research has highlighted increased output as a persistent concern for people living with an ileostomy beyond the post-operative period, with as many as 86.6% struggling with loose or watery output and 62.5% experiencing HOS(Reference Mitchell, England and Atkinson7). Poor treatment of, or prolonged HOS, can lead to depletion of electrolytes (sodium, calcium, magnesium)(Reference Almendingen, Fausa and Høstmark23,Reference Rud, Brantlov and Quist38,Reference Ng, Pither and Wootton47) and impaired kidney function(Reference Nightingale52).

It appears that the incidence of nutritional deficiencies in people living with an ileostomy is multifactorial and may be attributed to reduced absorption, underlying disease resulting in ileostomy, dietary restriction or varying combinations of all three. Nevertheless, it is apparent that people living with an ileostomy may be at increased risk of nutritional deficiencies and insufficiencies. Despite this, there are currently no guidelines surrounding routine nutritional supplementation for people living with an ileostomy(Reference Michońska, Polak-Szczybyło and Sokal3), and few studies have reported on supplement usage within this population.

Reasons for food avoidance

To improve dietary intake and therefore nutritional status of people living with an ileostomy, it is important to understand the factors contributing to dietary restriction within this group. Qualitative data indicates that health professionals recognise the importance of supporting patient autonomy to promote dietary reintroduction(Reference Mitchell, Herbert and England8); however, an explanation for continued dietary restriction from practitioners’ perspectives is omitted from this evidence. However, reasons for food avoidance reported by people living with an ileostomy are well documented (n = 12 studies) and summarised in Table 1.

Attempts to minimise ileostomy-related symptoms (flatulence, increased output, unpleasant odours, stomal blockages) appears to be the most prevalent reason for food avoidance reported by multiple ileostomy cohorts(Reference Bingham, Cummings and McNeil17,Reference Gooszen, Geelkerken and Hermans21,Reference Richbourg25,Reference Morris and Leach26,Reference de Oliveira, Mendez and Pereira Netto28,Reference de Oliveira, Boroni Moreira and Pereira Netto29,Reference Drozd, Veissetes and Sancisi34,Reference England, Mitchell and Atkinson37) . Such unpleasant symptoms may be exacerbated by underlying food sensitivities and intolerances(Reference Morris and Leach26,Reference England, Mitchell and Atkinson37) . For example, in a cohort of participants who had undergone ileostomy (n = 17) or ileo-anal pouch anastomosis (n = 61) surgery, 87% of participants reported suffering from at least one dietary intolerance before and/or after the surgical procedure, with 34% of reporting intolerances developing post-operatively. The formation of an ileostomy may predispose patients to dietary intolerances, meaning specific foods will exacerbate GI symptoms, potentially worsening dietary restriction. High-fibre foods were the most commonly reported intolerance (26%) and as a result often lead to long-term persistence of dietary restriction(Reference Schmidt, Wiesenauer and Sitzmann59). The prevalence of circulating food-specific immunoglobulin G in people living with an ileostomy has also been reported elsewhere(Reference Carson, Baumert and Clarke60). Although the reasons for this are unclear, it has been suggested that removal of the colon disrupts immune function, increasing prevalence of food intolerances in people living with an ileostomy(Reference Carson, Baumert and Clarke60). The direct impact of these intolerances on overall dietary intake is not reported in the literature; however, the need to manage GI and ileostomy-related symptoms is a major barrier to achieving a balanced, less restrictive diet.

The Ostomy Life Study (2019) identified pouch leakage as a major burden for people living with a stoma, and dietary intake was identified as the predominant factor related to the incidence of leaks, with 49% of participants associating ‘eating certain foods’ with leakage events(Reference Osborne, White and Aibibula61). Dietary intake was not reported in this study, and so it is difficult to determine the full impact of this association with food avoidance and restriction behaviours. However, a study by de Oliveira et al. observed that 20% of ostomates avoided foods for fear of pouch leakage, with fruits and vegetables identified as the most problematic foods(Reference de Oliveira, Boroni Moreira and Pereira Netto29) and dietary control highlighted as a key strategy in the mitigation of leaks(Reference Simpson, Pourshahidi and Davis62).

As people living with an ileostomy tend to identify consumption of specific foods with GI symptoms, it is also common for this population to adapt meal timings and frequency to lessen severity of such symptoms when partaking in social activities(Reference Drozd, Veissetes and Sancisi34), with ‘leaving home’ being identified as a key motivator for food avoidance in a cohort of ostomates (n = 103)(Reference de Oliveira, Boroni Moreira and Pereira Netto29), and previous qualitative investigations have described the anxiety experienced by people living with an ileostomy when eating outside of home(Reference Morris and Leach26). This highlights the implications of diet and ileostomy beyond nutritional status and symptom management and is indicative of potential impacts on mental health and QoL for people living with an ileostomy(Reference Mitchell, England and Atkinson7,Reference Kalayci and Duruk35,Reference Jansen, van Uden-Kraan and Braakman63) . In fact, evidence suggests a link between altered dietary behaviour post-ileostomy and diminished QoL(Reference de Oliveira, Mendez and Pereira Netto28,Reference Beeken, Haviland and Taylor30) with dietary restriction to any degree being strongly correlated with reduced QoL (P = 0.003, r = 0.28)(Reference Alharbi, Ahmad and Alhedaithy36).

Whilst symptom management is the most reported reason for food avoidance, more recent evidence suggests that current dietary advice for people living with an ileostomy may be the prime contributor to patterns of dietary restriction and food avoidance. England et al. (2023) asked people living with an ileostomy to identify drivers of dietary restriction; being ‘advised to avoid’ certain items was identified as the principal reason for people living with an ileostomy excluding food(s) and or drink(s) from their diet in the short- and long-term. Fruits and vegetables, nuts, high-fibre foods and to a lesser extent, spicy foods and drinks (e.g., carbonated beverages), were all avoided by people living with an ileostomy because of advice received(Reference England, Mitchell and Atkinson37). This contradicts the considered view that people living with an ileostomy should be encouraged to reintroduce foods after the post-operative period(Reference Mitchell, Herbert and England8–Reference Burch10). Therefore, this presents a disparity between the dietary intake of people living with an ileostomy – particularly those with well-established ileostomies – and the current dietary guidance for this group. Dietary advice which lacks clarity and consistency presents a barrier for people living with an ileostomy in achieving and maintaining good nutrition(Reference Morris and Leach26).

Further, studies suggest the provision of dietary advice to people living with an ileostomy also lacks consistency, with as many as 31% of people living with an ileostomy reporting never having received any dietary advice(Reference Mitchell, England and Atkinson7) and 50% going without nutritional recommendations relating to management of HOS(Reference Arenas Villafranca, López-Rodríguez and Abilés53). To reduce dietary restriction and food avoidance in this group, it is important to ensure the accessibility of appropriate dietary advice and resources for people living with an ileostomy.

Improving dietary intake and nutritional status for people living with an ileostomy

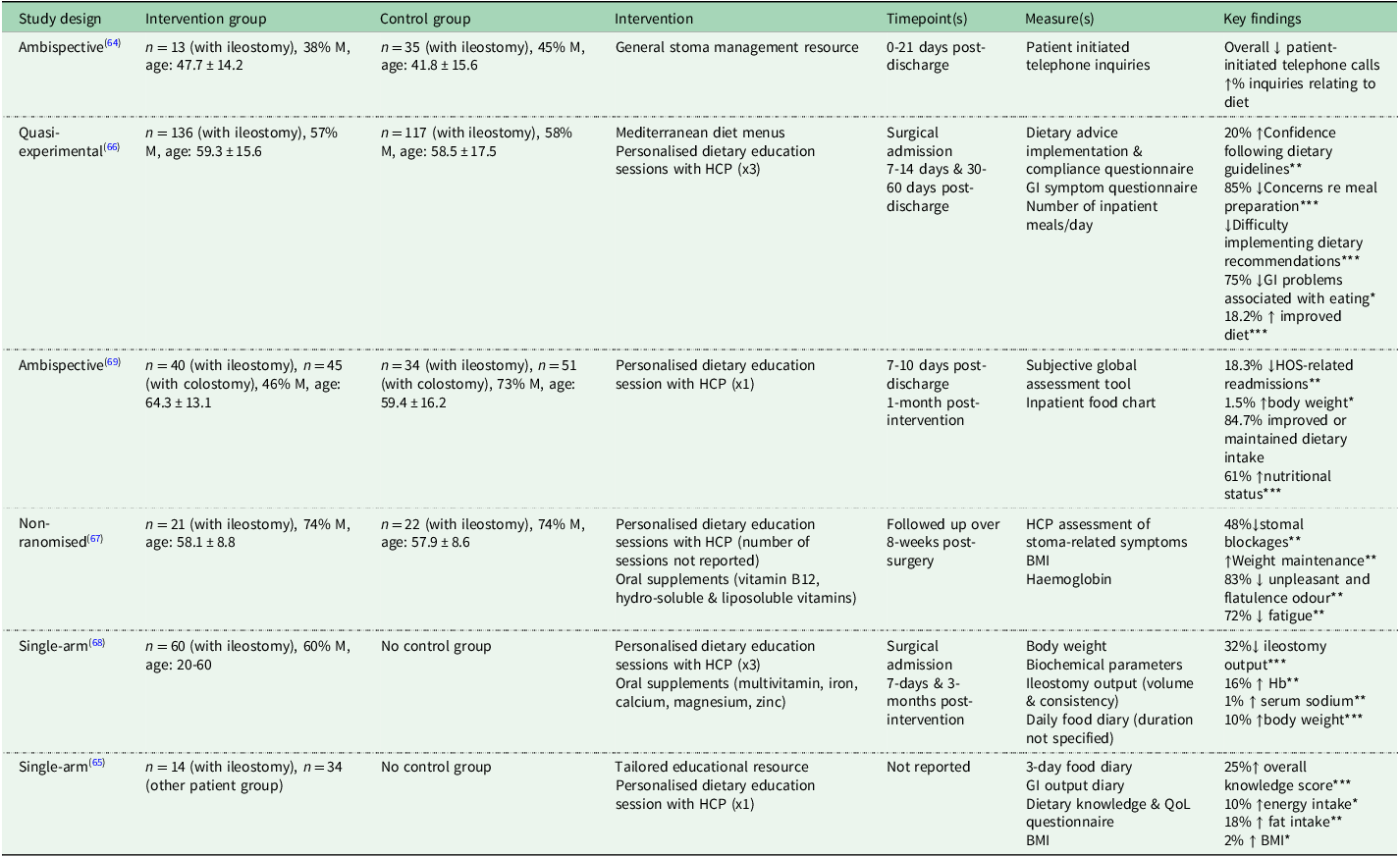

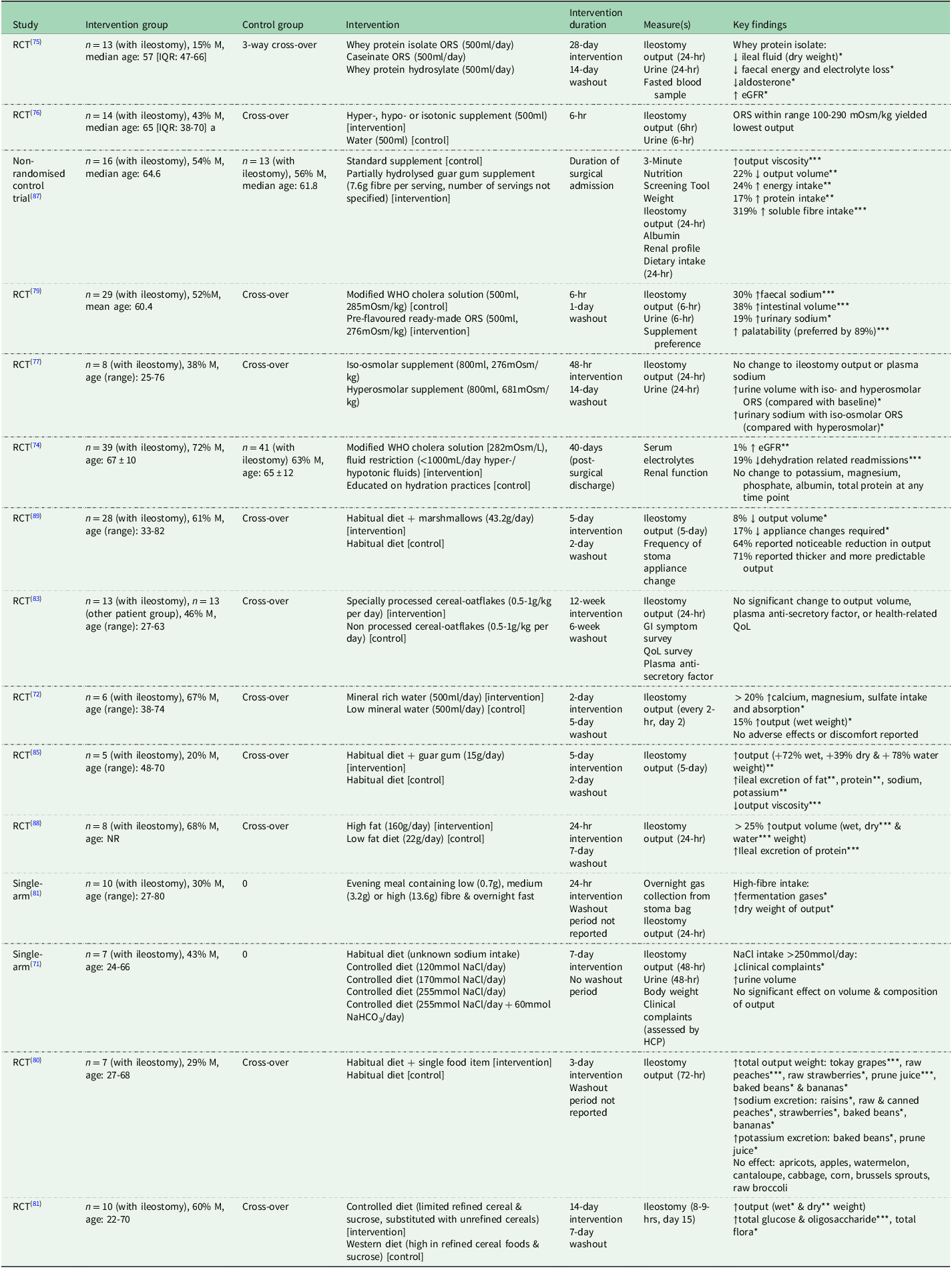

Considering the impact of ileostomy surgery on dietary behaviours and associated risk of nutritional deficiencies and diminished QoL, there is a clear need for solutions to improve this group’s intake and reduce dietary restriction. Educational and dietary interventions in people living with an ileostomy are summarised in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

Table 2. Educational interventions targeting dietary intake and nutritional status of people living with an ileostomy (n = 6)

Abbreviations: M, males; HCP, health care professional; GI, gastrointestinal; HOS, high output stoma; BMI, body mass index; Hb, haemoglobin; QoL, quality of life.

*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Table 3. Dietary interventions targeting hydration status or gastrointestinal symptoms in people living with an ileostomy (n = 15)

Abbreviations: RCT, randomised control trial; M, males; ORS, oral rehydration solution; hr, hour; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; WHO, World Health Organisation; GI, gastrointestinal; QoL, quality of life; NR, not recorded; NaCl, sodium chloride; NaHCO3 sodium bicarbonate; HCP, health care professional.

*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Educational interventions

Interventions providing generalised dietary advice in relation to ileostomy have produced limited benefits(Reference Roeung, Lindgren and Carley64); however, evidence for the efficacy of tailored nutritional advice is more convincing(Reference Culkin, Gabe and Madden65–Reference Santamaría, Villafranca and Abilés69). For instance, when patients suffering from intestinal failure (n = 14 with ileostomy) were provided with a dietary information booklet, alongside a verbal explanation from a dietitian adapted to their individual requirements, improvements were seen in participants’ dietary knowledge scores (25% increase, P < 0.001), nutritional intake (increased energy [+10% or +887kJ/day; P = 0.04], fat intake [+18% or +17g/day; P = 0.003]) and weight maintenance (increased BMI [+2% or +0.5kg/m(Reference Hill2); P = 0.02])(Reference Culkin, Gabe and Madden65). A similar study followed patients for the first 60-days post-discharge(Reference Fernández-Gálvez, Rivera and Durán Ventura66); the intervention group, provided with Mediterranean diet menus and one-one educational sessions (covering nutrition information and individual eating habits) with a stoma care nurse, showed significant improvements in diet (OR 3.68; CI95% [1.67–8.13]; P < 0.001), GI symptoms (OR 0.06; CI95% [0.03–0.12]; P < 0.001), meal preparation concerns (OR 0.07; CI95% [0.03–0.17]; P < 0.001) and adherence to dietary guidelines (OR 0.09; CI95% [0.00–0.66]; P = 0.005)(Reference Fernández-Gálvez, Rivera and Durán Ventura66). Comparable interventions also resulted in a significant reduction in dehydration-related readmissions (OR 2.78; CI95% [1.23–6.27]; P < 0.01)(Reference Santamaría, Villafranca and Abilés69), and minimising ileostomy-related symptoms (increased output, stomal blockages, unpleasant odour, flatulence)(Reference Mogos, Chelan and Dondoi67,Reference Mukhopadhyay, Maity and Dey68) .

This evidence underscores the value of individualised dietary guidance, particularly given reports of declining energy intake and BMI after ileostomy surgery(Reference Vasilopoulos, Makrigianni and Polikandrioti12–Reference Mohil, Narayan and Sreenivas14). However, it is important to note the limitations of these educational interventions; all the studies to date have utilised retrospective or non-randomised designs, therefore reducing the robustness of the results. Importantly, the methods used to assess dietary intake across studies varied, including daily food diaries(Reference Culkin, Gabe and Madden65,Reference Mukhopadhyay, Maity and Dey68) and inpatient food charts(Reference Fernández-Gálvez, Rivera and Durán Ventura66,Reference Santamaría, Villafranca and Abilés69) , which may influence both the accuracy and comparability of reported outcomes. Furthermore, these interventions mainly targeted people living with an ileostomy in the early post-operative period; although this may be the opportune time for the provision of dietary support, it is worth noting that advice is not routinely provided to people living with an ileostomy post-operatively(Reference Mitchell, England and Atkinson7), and dietary restriction is prevalent in people living with an ileostomy regardless of time elapsed since surgery(Reference England, Mitchell and Atkinson37). Future research should include randomised interventions to further strengthen the body of evidence regarding the benefits, and need for, specialised dietary advice and support for people living with an ileostomy during and beyond the post-operative period.

Dietary interventions

Mineral balance and oral rehydration solutions

Dehydration and electrolyte imbalances remain major issues for people living with an ileostomy(Reference Almendingen, Fausa and Høstmark23,Reference Rud, Brantlov and Quist38,Reference Ng, Pither and Wootton47) ; however, relatively few interventions to date have addressed strategies for management and prevention of increased and HOS (n = 7). People living with an ileostomy are often advised to add an extra teaspoon of salt (∼6g) to their diet to prevent or alleviate symptoms of dehydration(Reference Hill2,Reference Fulham4,Reference Cronin9,Reference Nightingale52) , contradictory to general dietary guidance which advises daily salt intake under 6g(70). There is currently no evidence for the consequences of following this dietary advice (i.e. a high salt diet) on people living with an ileostomy’ health. Further, to date, only one study has investigated the potential benefits of increasing sodium intake in people living with an ileostomy. Here, a significant decrease in clinical complaints was observed when sodium intake was increased > 250mmol/day(Reference Haalboom, Poen and Struyvenberg71); ∼3 times the recommended daily amount(70). Other strategies aiming to improve hydration in people living with an ileostomy include supplementation with mineral rich water, which improves absorption of magnesium (+30%, P = 0.028), calcium (+45%, P = 0.027) and sulphate (+197%, P = 0.028) without having any adverse effects on ileostomy output(Reference Normén, Arnaud and Carlsson72).

Oral rehydration solutions (ORS) are balanced glucose-electrolyte solutions(73), commonly used to treat HOS in people living with an ileostomy(Reference Nightingale52). Studies in acute cohorts have proven that treating HOS with hypo- or isotonic ORS is effective in decreasing rate of dehydration related readmissions(Reference Migdanis, Koukoulis and Mamaloudis74) by lowering volume of stomal output(Reference Rud, Hvistendahl and Langdahl75,Reference Quist, Rud and Frumer76) , increasing urine volume(Reference Rud, Pedersen and Wilkens77), lowering electrolyte losses and improving kidney function(Reference Rud, Pedersen and Wilkens77); these findings and other dietary interventions are summarised in more detail in Table 3. However, the palatability of ORS is a major issue for patient compliance(Reference Bradley, Vitous and Marzoughi78,Reference Culkin, Gabe and Nightingale79) and can therefore adversely impact the efficacy of these treatments. Further, effective management of HOS in the community setting should be considered, given the prevalence of dehydration-related readmissions within this population(Reference Justiniano, Temple and Swanger55). A recent study investigated the impact of commercially available hypo-, iso- and hyperosmolar oral supplements on ileostomy output and hydration status. Although none of the supplements tested had a significant effect on natriuresis or urine volume, those with osmolality ranging from 100–290 mOsm/kg yielded the lowest ileostomy output (e.g., semi-skimmed milk [278mOsm/kg], Powerade [293mOsm/kg])(Reference Quist, Rud and Frumer76), thus presenting a broader range of widely accessible and more palatable treatment strategies for HOS.

Management of ileostomy-related symptoms

Much of the dietary advice provided to people living with an ileostomy focuses on controlling dietary fibre to minimise ileostomy-related symptoms(Reference Burch10); however, few studies have examined the impact of altering fibre intake on such symptoms(Reference Kramer80–Reference Pagoldh, Eriksson and Heimtun83,Reference Ho, Majid and Jamhuri87) . An earlier study investigated the effect of adding specific foods to the diets of people living with an ileostomy (N = 7). Fruits like bananas and strawberries significantly increased output weight (P < 0.05), and other high-fibre foods (e.g., baked beans) also increased output and mineral losses (P < 0.05). Surprisingly, commonly avoided foods such as cabbage and broccoli had no effect, highlighting individual variability(Reference Kramer80). Larger studies are needed to better understand these impacts. More generally, randomised control trials have demonstrated that increasing fibre intake results in a significant increase in ileostomy output(Reference Berghouse, Hori and Hill81,Reference Gaffney, Buttenshaw and Stillman82) , and diets high in unrefined cereals have been associated with higher ileal microbiota concentrations (P < 0.02)(Reference Berghouse, Hori and Hill81), and therefore greater production of fermentation gases (P < 0.05)(Reference Gaffney, Buttenshaw and Stillman82), and presumably flatulence. These findings highlight the ileostomy-related symptoms associated with consumption of high-fibre food(s), consistent with reasons for food avoidance reported in the literature(Reference Bingham, Cummings and McNeil17,Reference Gooszen, Geelkerken and Hermans21,Reference Richbourg25,Reference Morris and Leach26,Reference de Oliveira, Mendez and Pereira Netto28,Reference de Oliveira, Boroni Moreira and Pereira Netto29,Reference Drozd, Veissetes and Sancisi34,Reference England, Mitchell and Atkinson37) . While identifying strategies to manage these symptoms would be more effective in supporting dietary inclusion among people with an ileostomy, the available evidence remains limited (presented in Table 3).

Specially processed cereals (SPC) (i.e. treated Nordic oatflakes) have previously been observed to stimulate production of anti-secretory factor and therefore have an anti-diarrheal effect. Consequently, it was hypothesised that supplementing 13 people living with an ileostomy’ diets with SPC-flakes over a 12-week period would lessen stomal output. No change occurred to output volume or plasma anti-secretory factor in response to the dietary intervention(Reference Pagoldh, Eriksson and Heimtun83). Alternatively, guar gum (GG) is a high molecular weight polysaccharide with the ability to form viscous solutions(Reference Rao84) and so supplementation with GG (15g/day) has previously been investigated as a potential treatment for HOS in people living with an ileostomy, however adverse effects were observed (wet, dry and water weight of output increased [+72%, +39% and +78% respectively, all P < 0.01] and viscosity decreased [P < 0.001])(Reference Higham and Read85). Partially hydrolysed guar gum (PHGG) is more widely used in dietary supplements due to its higher solubility(Reference Rao84) and has been proven to be effective in reducing diarrhoea symptoms in other cohorts(Reference Giannini, Mansi and Dulbecco86). In people living with an ileostomy, supplementation with PHGG has been shown to decrease output volume (22.1% reduction, P = 0.004) and increase viscosity according to the Bristol Stool Chart (P < 0.001)(Reference Ho, Majid and Jamhuri87) despite its lower water-binding capacity. In this study, dosage of PHGG was not specified, which could have provided an explanation for these inconsistent findings. Higher doses of GG and PHGG delay gastric emptying and increase retention of intestinal fluid(Reference Rao84), presumably resulting in a more liquid output of greater volume. More research is needed to better understand the impact of manipulating fibre intake in the management of ileostomy-related symptoms.

Other food(s) and food groups can also impact ileostomy-related symptoms and can therefore influence dietary behaviours. For instance, a higher daily fat intake (160g/day) significantly increased ileostomy output (P < 0.001) when compared with output when following a low-fat diet (22g/day)(Reference Higham and Read88). Further, consumption of marshmallows (43.2g/day) in addition to habitual diet resulted in thicker and more predictable output (reported by 71% of participants), of significantly lower volume (75ml/day or 8% reduction in daily output; CI95% [23–687]; P < 0.01,)(Reference Clarebrough, Guest and Stupart89). It is hypothesised that the ability of gelatine (in marshmallows) to form a semi-solid colloid gel when in solution, may partly explain the thickened/reduced output following marshmallow consumption. Before results of this randomised controlled trial were available, advice to consume marshmallows was routinely provided to people living with an ileostomy(Reference Fulham4), yet largely based on anecdotal evidence, despite a plausible mechanism. However, although marshmallow consumption has shown a statistically significant reduction in output volume, it is important to consider if the effect is of clinical significance to people living with an ileostomy suffering from increased or high output stomas. Further, it should be noted that several other foods are commonly recommended to people living with an ileostomy to help alleviate unpleasant symptoms; however, there is limited clinical evidence to support the efficacy of this advice.

Future research

People living with an ileostomy are at greater risk of undernutrition due to patterns of dietary restriction; however, it is unclear to what degree; to date only relatively small cohorts have been observed. Larger studies which investigate both nutritional intake and nutritional status, taking into consideration other factors which may impact nutritional status/absorption (e.g., underlying disease resulting in surgery, length of small intestine remaining) of people living with an ileostomy are needed to better understand the link between these. Further, the impact of limiting intake of phytochemical-rich foods (such as fruits and vegetables) on long-term health of people living with an ileostomy should also be considered,

To improve dietary intake of people living with an ileostomy, the drivers of food avoidance should be addressed, namely management of ileostomy-related symptoms, dietary advice and stoma pouch leakage. Strategies for the dietary management of ileostomy-related symptoms are well documented, and Mitchell et al. (2020) note an abundance of available dietary support services and resources for people living with an ileostomy, including formal clinical support, informal support from online sources or support associations(Reference Mitchell, England and Atkinson7). However, this can result in the provision of conflicting advice and therefore confusion for people living with an ileostomy(Reference Morris and Leach26). Further research is needed to understand the challenges faced by people living with an ileostomy when implementing dietary advice. Moreover, current dietary guidance tends to be based on expert opinion and clinical experience, rather than clinical evidence(Reference Burch10); it is vital that the dietary advice provided to people living with an ileostomy is evidence based, therefore future studies should seek to validate existing guidance, providing much needed reassurance to people living with an ileostomy and health care professionals alike. There is currently no evidence for adapting dietary intake to minimise the incidence of leaks, despite reported associations between diet and pouch leakage(Reference Osborne, White and Aibibula61,Reference Simpson, Pourshahidi and Davis62) . Future research should address this gap in research, to both lessen the burden of leaks for people living with an ileostomy and to indirectly improve dietary intake.

Conclusion

Dietary restrictions are highly prevalent in people living with an ileostomy, persisting long after surgery and often driven by attempts to mitigate unpleasant symptoms (blockages, increased output, flatulence, odour). Prolonged avoidance of nutrient and fibre-rich foods such as fruits and vegetables, in combination with people living with an ileostomy’ reduced absorbative capacities, can contribute to nutrient deficiencies, reduced overall health and diet-related QoL. Evidence demonstrates the positive impacts of personalised dietary advice for people living with an ileostomy on both quality of life and nutritional outcomes, yet current general guidance lacks clarity and tends to emphasise dietary restriction. To inform the development of effective and consistent guidance, further exploration of dietary management for ileostomy-related symptoms is needed, supporting the integration of personalised, evidence-based care into current practice.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualisation and structure of the current review. N.M. drafted the initial manuscript. All authors contributed to reviewing, editing and writing the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare none.

Financial Support

This work was completed as part of a PhD studentship (N.M.) awarded by the Department for the Economy (DfE).