Introduction

The imperative for food system transformation is well known and concerted UK action is essential to impact inter-related food system issues including health inequalities and diet-related disease(1). Key to this effort is enabling materially deprived (disadvantaged) communities(2,3) better access to healthy, affordable, sustainable food(4).

In the context of food systems, to date, minimal research has investigated ‘blue foods’(Reference Nicolini, Bladon and Clarke5) i.e. foods sourced from oceans and rivers, including fish(Reference Tigchelaar, Leape and Micheli6), probably because they are ethically nuanced. There exists a paradox. On the one hand, fish is culturally important(Reference Martino, Azzopardi and Fox7), providing essential nutrients(Reference Ruxton8) that protect from non-communicable diseases(Reference Jamioł-Milc, Biernawska and Liput9). Most UK residents do not eat the recommended amount of fish (two portions/week, one portion of oily fish)(Reference Gale, Aboluwade, Hunt and Pettinger10). A clear health inequality is that vulnerable groups, such as those living in areas of material deprivation, eat low-quality diets, have poor health outcomes, and are most likely not to eat enough fish. On the other hand, eating fish is an environmental ‘red flag’ because of global overfishing(11). In response to these various complexities, collaborative and innovative solutions are required to catalyse change in the (blue) food system.

This review paper presents a critique of the ‘The Plymouth Fish Finger’ as a collaborative social innovation case study(Reference Hunt, Pettinger, Tsikritzi and Wagstaff12) which exemplifies and pioneers food system change. Part of the Food Systems Equality (FoodSEqual) research project(4), this exploratory pilot project championed ‘co-production’ approaches(Reference Shaw, Hardman and Boyle13) to achieve multiple (potential) impacts including: i) ‘disruption’ of traditional fish supply chains, by localising processes; ii) improving access to and affordability of fish for local (coastal) communities, particularly those living in areas of material deprivation; iii) education about less common fish species, how to prepare and cook these, and their health and sustainability credentials; iv) enhancing fishing community livelihoods by giving fishers a fair price for their catch; v) informing policy and ‘blue food system’ discourses, using learned processes to support this impact.

The review paper starts with an outline and definition of the blue food system and blue foods, including their essential nutritional and wellbeing benefits. It will emphasise the needs of materially deprived coastal communities, who are known to suffer the most in terms of diet related health inequities and resulting poor health outcomes. It will then use the fish finger pilot as exemplar to appraise the need for ‘social innovation’ as a collaborative mechanism to champion blue food system change. This will include judging the range of participatory methods used, which successfully forged relationships between multiple stakeholders including academics, communities, fishing industry stakeholders, schools, school meal providers and policy makers. The review will close with critical reflections on key challenges and learning, offering recommendations for future research, as well as reflective insights for professional practice.

What are ‘blue foods’ – the blue food system

Blue foods are defined as ‘fish, invertebrates, algae and aquatic plants captured or cultured in freshwater and marine ecosystems (Reference Bennett, Basurto and Virdin14). They tend to be foods harvested from the ocean, rivers and lakes, including wild and farmed seafood(15). Blue foods contribute importantly to national food systems around the world. For the purposes of this review, the focus is on fish, yet it is important to consider there are many other blue foods, eg algae and aquatic plants, which are emerging as important nutrition topics, but fall outside the scope of this review. They ensure supplies of critical nutrients, provide healthy alternatives to terrestrial meat and therefore reduce dietary environmental footprints, promote just economies and livelihoods under a changing climate(Reference Crona, Wassénius and Jonell16). This is why the United Nations have prioritised a ‘Blue transformation’ in their recently published roadmap/strategy(17), supported by Eat Lancet(Reference Rockstrom18), both acknowledging that our oceans should form part of solutions to improve global food security. Despite this, to date, most food system discourses have centred on livestock and land-based agriculture(Reference Tigchelaar, Leape and Micheli6) with blue foods being largely missing from food system transformation research(Reference Nicolini, Bladon and Clarke5).

The benefits of blue foods (fish)

Blue Foods play a central role in food and nutrition security for billions of people(Reference Tigchelaar, Leape and Micheli6). Fish and seafood provide essential nutrients for humans(Reference Ruxton8,19) and are known to have a prominent role in protecting humans against non-communicable diseases(Reference Jamioł-Milc, Biernawska and Liput9,Reference Verbeke, Sioen and Pieniak20) . Commonly promoted to reduce the prevalence of these diseases, they have been cited as major commodities within ‘healthier’ diets such as the Mediterranean diet(Reference Willett, Sacks and Trichopoulou21,Reference Romagnolo and Selmin22) and the DASH diet(Reference Umemoto, Onaka and Kawano23,Reference Soltani, Shirani and Chitsazi24) and have a prominent place within the UK’s Eatwell Guide(25).

Fish contains high-quality protein, and due to its low saturated fat content, is often considered a healthier protein choice than meat(Reference de Boer, Schösler and Aiking26), although this depends on the fish type and cooking method. Fish (especially oily) is a major source of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), known as omega-3 fatty acids(Reference Harris27). These long chain fatty acids (LC n-3 PUFA) play an essential role in health benefits with evidence suggesting that consumption of oily fish has an inverse effect on risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD), attributed to its LC-n-3 PUFA content(19,Reference Rimm, Appel and Chiuve28,Reference Khan, Lone and Khan29) . Fish is also an important source of essential micronutrients, including vitamins A, B and D, and minerals including calcium, iron, and zinc(Reference Tacon, Lemos and Metian30). Fish intake is also known to positively contribute to improved nutrient profiles for Vitamin A(Reference Roos, Wahab and Chamnan31) and vitamin B12 status(Reference Scheers, Lindqvist and Langkilde32). Fish consumption (especially oily fish) increases concentrations of 25(OH) D in the blood(Reference Lehmann, Gjessing and Hirche33).

Current UK guidance recommends 2 portions of fish a week, 1 oily fish(34). Despite the UK showing relatively stable fish-eating trends over the past two decades(35), purchasing data show a slight downward trend of fish intake, with preference for ‘the big five’ species (cod, haddock, salmon, tuna and prawns), according to the Marine Stewardship Council report(36). The consumption of oily fish, however, is well below the dietary recommendations of government guidelines(19,25) and shows significant disparities across socio-economic status groups(Reference Gale, Aboluwade, Hunt and Pettinger10).

Fish eating has cultural significance(Reference Martino, Azzopardi and Fox7) which is a known driver influencing its consumption behaviours. For example, socialisation and inter-generational transmission of food choices (from parents to children) can influence fish consumption, family habits and preferences(Reference Hardcastle and Blake37,Reference O’Neill, Rebane and Lester38) and this is particularly marked in lower socio-economic communities(Reference Gale, Aboluwade, Hunt and Pettinger10) where often children’s dislike of fish is learnt from parent. The latter is likely influenced by education level and lack of confidence in cooking fish(Reference Adam, Goffe and Adamson39,Reference Burns, Bhattacharjee and Darlington40) . Education and literacy levels around fish are known to be low in the UK(Reference Clarke, McKinley and Ballinger41) which is why educational and promotional strategies are needed to boost fish intake, especially amongst lower socio-economic groups(Reference Gale, Aboluwade, Hunt and Pettinger10).

‘Less affluent’ communities are defined as ‘individuals and families at risk of food and housing insecurity, often culturally diverse, who can experience multiple challenges; financial, mental health, physical health’(4) including ‘material deprivation’(2). There remains a paradox whereby such communities should be eating more fish to fulfil their nutritional health, yet global fish stocks are massively depleting(11). The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization monitors over 2,000 fish stocks around the globe. Its 2025 report estimates that 35.5% are fished at unsustainable levels(42). Over-fishing and poor fishing practices have impacted on fishing stocks with an estimated 90% of fisheries now fully exploited, the marine vertebrate population has been halved, and the marine ecosystem has been damaged(43). This is why blue food system reform is so urgently needed.

Nutritional health and fish intake of ‘less affluent’ (coastal) communities in the UK

It is well established that dietary patterns are strongly associated with socio-demographic characteristics(Reference Roberts, Cade and Dawson44) with lower SES groups less likely to consume diets aligned with public health guidance(Reference Maguire and Monsivais45). UK coastal communities are particularly at risk of health inequalities and poorer health outcomes(46). Plymouth, as a southwest coastal community, for example, has persistent, complex and distinct spatial clustering of deprivation(Reference Argawal, Jakes and Essex47) contributing to extreme social and economic inequalities. Local evidence shows those on the lowest incomes suffer disproportionately from poor nutrition(Reference Burnett, Hallam and Kirby48) due to a range of complex needs with well-established evidence of escalating food insecurity across the city(Reference Pettinger and Elwood49) associated with poor health outcomes (Figure 1 overleaf).

Figure 1. Map of Plymouth (UK) illustrating areas of deprivation using food insecurity data. With permission, adapted from(Reference Smith, Rixson and Grove50) with updated data coming from(51).

There are marked socioeconomic inequalities in UK fish consumption(Reference Gale, Aboluwade, Hunt and Pettinger10) - lower socio-economic groups have lower fish intake compared to higher income groups(Reference Ruxton8,Reference Bates, Lennox and Swan52) , especially oily fish intake (EPA and DHA sources). Furthermore, coastal fishing communities are particularly at risk of poverty, particularly the small boat fishers(Reference Lewis, Hatt and Coulthard53) who have been marginalized from dialogues about sustainable and equitable food system transformation(Reference Cohen, Allison and Andres54). This is influenced by (often corrupt) commercial interests(55) market instability (i.e., price volatility(Reference Rice, Bennett and Smith56) and unrealistic quota policies, the latter of which signifies that justice and ethics have been sacrificed to power and politics(Reference Gray57).

The need for collaborative and innovative solutions

There is a call for systemic, multi-level and multi-stakeholder participatory approaches for addressing interrelated issues across economic, social and environmental dimensions: the so-called ‘food systems approach’(58). Inclusive and collaborative approaches, therefore, should be prioritised and built upon to support transformative mechanisms within blue food system policy and decision-making. The engagement of multi-sectoral stakeholders(Reference Warren, Constantinides and Blake59) particularly the fishing community, is essential to support inclusive development and protection of human rights within the blue food sector(Reference Tigchelaar, Honig and Mega Laidha60). ‘Social innovation’ involves new strategies, practices, organisational designs and collaborations that address unmet social needs and failures of state and market-led provision. As a multi-stakeholder process and mode of governance, social innovation aims to be more inclusive, participatory and attuned to social wellbeing concerns compared to innovation that is primarily motivated by private profit(Reference Lyon, Doherty and Psarikidou61).

An example of good (collaborative) practice – The Plymouth Fish Finger

The Plymouth Fish Finger is an exploratory pilot project(Reference Hunt, Pettinger, Tsikritzi and Wagstaff12) which is a core output from a large UKRI/BBSRC funded food system transformation research project, running from 2021 - 2026 (Food Systems Equality (FoodSEqual)(4)). The pilot made use of local community action research intelligence, leading to a ‘social innovation’ aiming to improve access, affordability, and increase fish intake for local disadvantaged communities. Using a culturally appropriate and iconic British product ‘The Plymouth Fish Finger,’ innovation was collaboratively co-designed to be ‘healthy’ and ‘sustainable’. It makes use of low value and underutilised fish species (e.g., pouting, dogfish and whiting which are currently often wasted) caught by local small-scale coastal fishery (SSCF) vessels (under 10m which cause less environmental damage) and then processed with the intention of delivering the product into the local school meals system. The inclusive vision for the product is that it will improve fish intake in disadvantaged communities (children and their families), thus promoting health benefits. Furthermore, giving fishers a fair price for their low value under-utilised species means reducing fish waste, limiting environmental damage from overfishing and improving livelihoods in the fishing community(Reference Pettinger62,Reference Pettinger63) . We have called our fish finger pilot a ‘social innovation’ because it fulfils the relevant criteria of having a i) social enterprise/business model; ii) education and behaviour change input iii) and systemic/collaborative approaches(Reference Lyon, Doherty and Psarikidou61).

FoodSEqual has used a Community Food Researcher (CFR) model(Reference Pettinger, Hunt and Gardiner64) to catalyse change and innovate healthy and sustainable food systems with disadvantaged communities(4). Plymouth is one of its four UK FoodSEqual study sites. Drawn from within the community, Plymouth CFRs work as an integral part of the FoodSEqual research team to listen to peoples lived experience, what people eat and want to eat, identify food commodities of interest (i.e. fish), and establish community-driven innovation needs (i.e. access and affordability are key, exploring why locally caught fish not available in Plymouth communities).

The strength of collaborative approaches for (Blue) food system innovation

Multi-stakeholder collaboration is suggested as an essential pillar of the food systems approach and the transition to sustainable food systems(58). Developing meaningful food system transformation action planning requires the active involvement of a broad spectrum of stakeholders, including government, civil society, and private sector actors(Reference Lavado, Navarrete Frias and Declerck65). Authentic stakeholder engagement demands an inclusive, adaptive approach that fosters collaboration and the co-production of knowledge(Reference Ghodsvali, Krishnamurthy and De Vries66,Reference Kujala, Sachs and Leinonen67) . Sterner and Trouve(Reference Sterner and Trouvé68) suggest enabling factors to optimise stakeholder collaboration include maintaining open networks, sharing activities, and flexible agendas. They also stipulate perceived barriers such as lack of resources, assembling heterogeneous stakeholders around common relevant agendas, and difficulties with engaging new actors. Due to their complex multi-sectoral landscape, strategies to engage stakeholders in food systems research are often challenging to embed(Reference Warren, Constantinides and Blake59). This is particularly the case with the blue food system, where strategic reform is urgently called for(Reference Caveen, Stewart and Moffat69) with collaborative co-design of blue food policy and practice(Reference Tigchelaar, Honig and Mega Laidha60) suggested as priorities.

Furthermore, within the higher education academy, advocated by funders and scientists alike, there is a call for improved transdisciplinary research approaches in the transformation of food systems(Reference Schwarz, Vanni and Miller70) whereby all actor voices should be included, fairly, across the value chain, from production through to consumption. This requires additional consideration of capacity building strategies(Reference Den Boer, Broerse and Regeer71) which could lead to enhanced collaboration across different scientific disciplines as well as optimising multi-stakeholder engagement. A more systematic approach, therefore, to build authentic collaborations is important and has great potential to increase the impact of food systems research, activism and practice. The FoodSEqual project, with its transdisciplinary efforts and multi-stakeholder collaboration has advocated this way of working by using a range of tailored (creative participatory) approaches to build trust and relationships with a range of partners (particularly communities, but also diverse food systems stakeholders) to build a strong foundation towards food system transformation(Reference Wagstaff, Pettinger and Relton72). The blue food system urgently requires such attention(Reference Nicolini, Bladon and Clarke5,Reference Tigchelaar, Leape and Micheli6) so that collaborative action can ensue, to achieve strategic priorities(Reference Caveen, Stewart and Moffat69).

Participatory approaches to support (and maintain) collaboration

To successfully meet its objectives and optimally engage a diverse range of stakeholders, the ‘Fish Finger’ pilot project employed a range of creative participatory research methods (alongside more traditional research methods such as interviews and focus groups), focussing on ‘co-production’ approaches(Reference Shaw, Hardman and Boyle13). These involved but were not limited to:

The embedding of a community food researcher model(Reference Pettinger, Hunt and Gardiner64). The active involvement of community food researchers (CFR) was pivotal to ensuring the community was fully on board and authentically involved in project-related decision making.

Participatory workshops to enhance collaborative developments(Reference Pettinger, Parsons and Letherby73) for example community taste testing (also supported by CFR)(Reference Pettinger, Hunt and Gardiner74) enabled successful community engagement, stakeholder involvement and data collection (see also) Reference Methven, Smith and Zischka75 .

Interactive co-design with secondary school students(76,Reference Pettinger77) promoted as important in food system research to enhance engagement via experiential learning to enhance food literacy skills in young people(Reference Ares, De Rossa and Mueller78) which can build confidence in young people’s long-term food practices(Reference Carroll, Perreault and Ma79).

Pop-up educational sessions with primary school students (n = 92) to learn about the environmental sustainability side of the fish finger and taste test the product(Reference Hunt, Pettinger, Tsikritzi and Wagstaff12). These learning opportunities can be a powerful way to engage often marginalised stakeholders such as catering staff and local producers to mobilise school food partnerships which can generate mutual benefits(Reference Sabat and Bohm80). An education pack was produced from these sessions(81) and its implementation as a research intervention will be the subject of future research for the project.

Various public engagement activities, known for their importance for knowledge translation(Reference Pettinger, Parsons and Letherby73) have been hosted, involving multiple stakeholders, with several visual outputs, including film launch(Reference Pettinger63), zine(82) and song(83). All such visual outputs exemplify the multiple efforts to maintain strong collaborations across the project team and serve to enhance the projects impact and visibility.

Such participatory methods have become popular in food systems action research, because they are known to empower and engage a wider range of stakeholders in research processes, cultivating narratives of hope and getting more people involved in decision making(Reference Thomas Hughes84), many of whom have traditionally been marginalised from solutions (e.g. communities). The transforming the UK (TUKFS) research programme(85) has championed this way of working across a range of research activities. In a synthesis study carried out across a range of projects involved in this research programme(Reference Shaw, Hardman and Boyle13), authors identified four key shared principles for co-production within food systems research: (1) Relationships: developing and maintaining reciprocity-based partnerships; (2) Knowledge: recognising the contribution of diverse forms of expertise; (3) Power: considering power dynamics and addressing imbalances; and (4) Inclusivity: ensuring research is accessible to all who wish to participate. The fish finger project meets all these principles by fully supporting the involvement of multiple stakeholders. However, crucial understanding to this way of working is the discovery that ‘messiness’ and complexity are inherent challenges associated with applying co-production approaches for improved collaborative practices(Reference Shaw, Hardman and Boyle13).

The fish finger pilot project has enabled partnership working with local stakeholders to plan and deliver the project, to test the fish finger for acceptability, and to appraise the collaborative and co-production approaches adopted(Reference Hunt, Pettinger, Tsikritzi and Wagstaff12). Powerful and constructive stakeholder collaborations (effectively forming a ‘Community of Practice’) built around the project forged relationships between academics, communities, fishing industry stakeholders, schools, and school meal providers. Well considered and evidence informed techniques were used to optimise stakeholder engagement from the start of the project. As well as regular and focussed cross-sector team meetings, training was undertaken by the research team in how to apply systems thinking in a community food context(86). This enabled workshop discussions to be framed around established approaches, for example use of the BATWOVE framework(Reference Walsh87) supported (blue) food system visioning amongst a range of local/regional fishing stakeholders. A ‘BATWOVE’ exercise(Reference Midgley and Reynolds88) enables the exploration of complex situations involving transformative change from multiple perspectives. It is mnemonic, with each section analysed as part of the exercise: B = Beneficiaries; A = Actors; T = Transformation; W = Worldview; O = Owner(s); V = Victims; E = Environmental Constraints. Similarly, ‘backcasting’, as a participatory approach known to strengthen cross sectoral collaboration(Reference Remans, Zornetzer and Mason-D’Croz89) was used to connect potential innovation with broader systems-change visions, anticipating complexities and trade-offs. ‘Backcasting’ is a strategic planning exercise whereby participants envision an ideal future scenario and work backwards, figuring out the steps needed to get there(Reference Robinson90). Indeed, utilising ‘backcasting’ at an early stage of innovation development enabled the team to avoid pursuing actions that might have been problematic during roll out. By bringing together diverse partners and asking them to look into the future together, varied experiences and expertise were harnessed, revealing proposed challenges not initially obvious to all partners. Taking all voices seriously and acting on these concerns meant the avoidance of time-costly dead ends. Such collaborative efforts were challenging at times, but were worthwhile, as they built trust between stakeholders, offering valuable shared insights, knowledge, and learning that contributed to the development of transition pathways to accelerate blue food systems innovation(Reference Thornton and Mason D’Croz91). By taking the time to forge these strong relationships, capacity has been built, and shared visioning realised, both of which can effectively mediate between the interests of system actors, thus informing potential co-creation of the national blue foods strategy that is urgently called for in the UK(Reference Caveen, Stewart and Moffat69).

Critical reflections

Challenges and learning

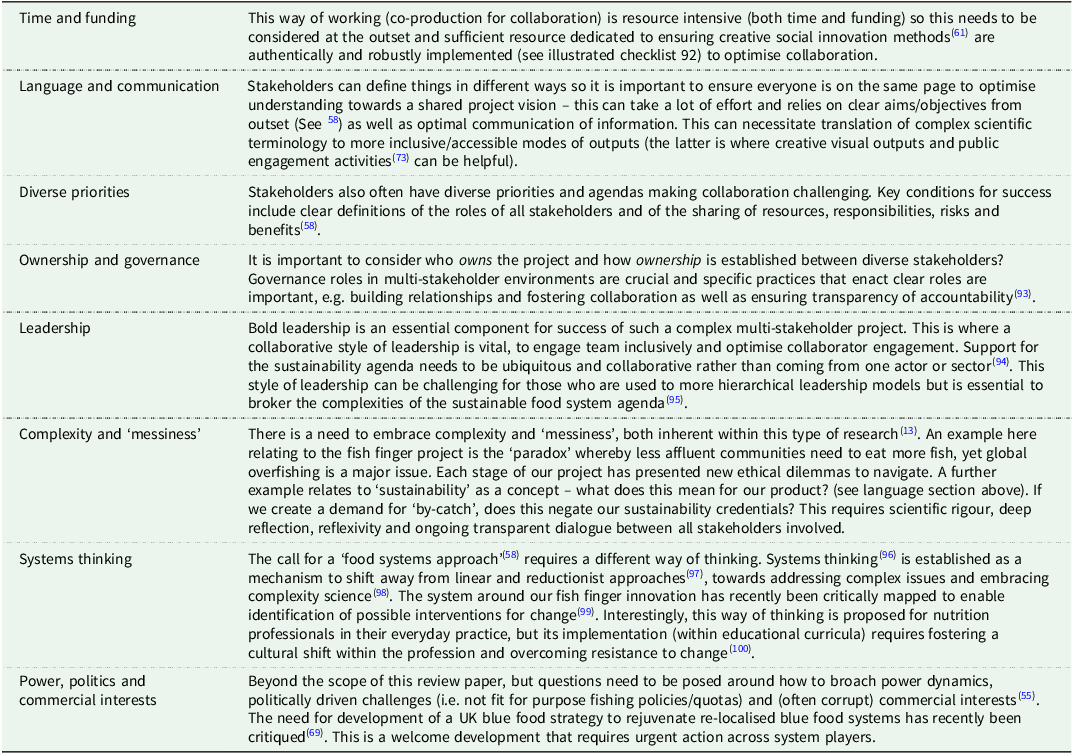

The concept of a community-led fish finger social innovation has been built, which serves to advocate for collaborative action towards (blue) food system transformation. Table 1 highlights (and critiques) key challenges and learning from implementation of these collaborative processes, informed by active stakeholder feedback. Signposting is also included for knowledge mobilisation and resources to support research and practice.

Table 1. Fish Finger project collaboration – challenges and learning

Future aspirations

The fish finger pilot project has generated a lot of interest across (local and national) blue food system stakeholders – a strong ‘Community of Practice’ has emerged around it, which is a positive outcome. But the project is by no means ‘complete’, until successful upscaling is implemented (the current focus of activity). Table 1 (above) goes some way to capture learning and knowledge on collaborations to date, but there is much learning still to happen and capturing this ongoing dynamic learning is pivotal to support project longevity. Similarly, as the project evolves, ongoing management of stakeholder engagement is crucial, to foster a sustainable model that can become a ‘blueprint’ with the option of replication in other (coastal) communities and for co-design/development of other food commodities/products.

There are many potential future research routes that can be recommended based on this collaborative pilot project. These include, but are not limited to: i) co-designing (with multiple stakeholders) interventions that support educational aspects for children and young people, to improve fish literacy and intake, especially in less affluent coastal communities; ii) exploring circular economic models to support the livelihoods and wellbeing of small boat fishers and the fishing community; iii) investigating robust metrics on how to measure ‘social innovation’ effectively(Reference Lyon, Doherty and Psarikidou61). Suggestions are emerging on suitable (participatory) methods that can be used to champion the complexities of transformational focussed evaluation(Reference Buckton, Fazey and Ball101) for food system change, which is a potential area of future research.

All such aspirations need to be carefully and sensitively mobilised for inclusive and optimal learning across diverse audiences and food system players. This requires meticulous attention being paid to robust public engagement strategies(Reference Pettinger, Parsons and Letherby73), that enable knowledge translation, co-producing good practice guides to support replicability of processes. In this way, acting as a ‘blueprint’ for collaborative solutions to increasing fish intake and improving fish supply chains for UK coastal communities. This can pave the way to better understand the causes of health inequalities and their link to the blue food system.

Personal reflections and (nutritional) professional/practice insights

Collaborative leadership(Reference Pettinger, Tripathi and Shoker95) and teamwork have been at the forefront of this project. This has meant understanding and an ‘over and above’ attitude and commitment. Our nutrition professional skillset already includes strong communication and compassion/empathy. More demanding perhaps is truly understanding the cross-sector needs and priorities of all players across the food system, but this is essential to build rapport, trust and transparency and break down power barriers(Reference Pettinger102). Care needs to be taken to fully acknowledge all collaborator input and engagement – whether that means emails of thanks, small gifts and/or other such personal touches, all of which can serve to reinforce human connection(Reference Cottam103).

This fish finger pilot ‘social innovation’ project journey has taught some interesting lessons from the perspective of a nutrition professional. Understanding that nutrition is a very small part of this very large systems puzzle. This does not diminish its importance of course but putting it in context especially where collaborators with different priorities are concerned, is a very useful message. This reinforces the need to embrace the ‘messiness’ and complexity(Reference Shaw, Hardman and Boyle13) associated with food systems research and action, which requires a mindset shift. Similarly, integration of systems thinking into nutrition curricula, to recognize interconnections, diverse perspectives and consider the big picture(Reference Gilbert104) is needed. Particular skills are required to navigate political and commercial interests(55).

Finding ways to navigate the identified ‘messiness’ and complexities(Reference Shaw, Hardman and Boyle13) of food systems research/action requires passion, patience, confidence and dedication. Nutrition professionals already possess a range of essential transferable skills, values and competencies. To amplify these, however, risks need to be taken, to step out of comfort zones and embrace new opportunities, evidence, perspectives and (creative) ways of working, all of which require personal, professional and creative courage(Reference Pettinger105).

We need to view our ever growing pressing social, political and cultural issues through a more ‘critical creative’ lens, embracing the uncomfortable challenges this presents(Reference Pettinger102, Reference Pettinger105). Self-compassion, as a core part of curious creativity, can galvanise action and inspire others, thus leaving an important legacy(Reference Aphramor106). Demonstrating holistic values can enable us to embrace a more adaptable, agile and flexible mind-set, and lead by example, focussing on collaboration, with people as assets, to build stakeholder capacity, citizenship and community connection.

Conclusions

The Plymouth fish finger collaborative ‘social innovation’ has shown great promise as an approach to benefit society: It has forged relationships between food system stakeholders (academics, community members, fishing industry stakeholders, school students, schools and school meal providers); It has successfully built the concept of a community-led fish finger product, advocating for improved nutritional wellbeing and collaborative action towards (blue) food system transformation; it has built a strong ‘Community of Practice’ to ensure its ongoing impact and longevity.

Through deliberative actions to collaborate with blue food system stakeholders, the project has demonstrated strong potential to optimise nutritional health and wellbeing in less affluent communities, thorough its ongoing inclusive vision to:

-

1) improve fish intake (& education/skills) in ‘less affluent’ communities (children and their families), thus promoting nutritional health benefits and tackling health inequalities

-

2) give fishers a fair price for low value, under-utilised ‘by-catch’, thereby reducing fish waste, limiting environmental damage from overfishing and improving livelihoods in the fishing community

-

3) contribute to a resilient local food economy (promoting, in particular, a circular economic approach to support future blue food system resilience) Reference Rizwan, Kirmani and Masoodi107 . This is a win-win for coastal communities(46,Reference Argawal, Jakes and Essex47) which are in urgent need of dedicated intervention and regeneration(Reference Burton, Balogun and Brien108).

Future (blue) food system research and practice can be shaped through more creative engagement practices, such as the participatory approaches critiqued in this article to optimise collaboration, because they harness energy, vision and skills development, thus enabling active agency and capability to be enhanced within system stakeholders and the communities they serve. This permits integration of more progressive solutions to persistent blue food system issues, informs the need for strategic reform and gives people a stronger voice to support the re-imagining of their own, more inclusive, co-operative and democratised system.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the many partners and stakeholders who have tirelessly engaged in this project, supporting collaborative activities, sharing knowledge and expertise as well as assisting with its delivery. Thanks go to Caroline Bennett (Sole of Discretion CIC); Ed Baker (Plymouth Fishing & Seafood Association CIC); Brad Pearce (CATERed Ltd), our community food researchers (Laura and Star); school children and teachers; Food Plymouth CIC.

Author contributions

CP created the concept for the presentation and drafted the review paper. LH as research fellow assisted with research design and ongoing engagement with multi-stakeholder collaboration. CW acquired funding, made substantial contributions to the conception of the FoodSEqual research project.

Financial support

This research is part of FoodSEqual, a large consortium project funded by the UKRI Strategic Priorities Fund 2021-2026 Transforming the UK Food System programme (BB/V004905/1). The funding body had no role in the study design, analysis or data interpretation.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.