Introduction

Recent studies show that it is essential to understand the factors underlying the reasons to (not) undertake volunteering among not only volunteers but also non-volunteers (Lockstone-Binney et al., Reference Lockstone-Binney, Holmes, Meijs, Oppenheimer, Haski-Leventhal and Taplin2022). There is an ongoing debate on how to encourage non-volunteers from the general population to join volunteering activities (Arnon et al., Reference Arnon, Almog-Bar and Cnaan2023) and how to prevent turnover in people already engaged (Nowakowska, Reference Nowakowska2024).

In the case of general population studies, delving into the intentions to volunteer in the future is crucial (Jiranek et al., Reference Jiranek, Kals, Humm, Strubel and Wehner2013). Changes in intentions lead to actual changes in behavior (Webb & Sheeran, Reference Webb and Sheeran2006), which confirms the theoretical suggestions that behavioral intentions are key to subsequent behaviors (Ajzen, Reference Ajzen1991).

In the current paper, we aim to answer the following research question: what motivates people from the general population to intend to volunteer in the future? To pursue this goal, in our two-wave longitudinal study, we test which individual differences related to the prosocial motivation paths outlined by Reykowski (Reference Reykowski and Staub1984) predict the intention to engage in volunteering in the future and contribute to shaping this intention over a 1-year period. We also intend to see whether these individual differences relate to each other over time.

The aforementioned theory by Reykowski (Reference Reykowski and Staub1984) takes into account motivational paths which are mentioned in other theories, but rarely examined together as parallel pathways to prosociality. It suggests three motivational paths that lead to prosocial behaviors: intrinsic (concentrated on other person’s welfare; similar to empathy-altruism hypothesis; Batson et al., Reference Batson, Lishner, Stocks, Schroeder and Graziano2015); endocentric (focused on staying congruent with self-standards and acting so as to avoid negative emotions or boost positive thinking about oneself; similar to theories that underline the ego-related motives for helping or altruism as hedonism concept; Cialdini & Kenrick, Reference Cialdini and Kenrick1976); and ipsocentric (concentrated on balancing costs and rewards from helping; similar to social exchange theories and concerns for reciprocity; Cropanzano & Mitchell, Reference Cropanzano and Mitchell2005). We argue that for each of these motivational paths, relatively stable individual differences exist, underlying the decisions to act prosocial (see also Nowakowska et al., Reference Nowakowska, Rajchert and Jasielska2024).

The theory is yet to be tested in the context of volunteering intentions in the general population. Our analysis may fill the research gap of understanding volunteering processes through the lens of individual differences psychology (Kragt, Reference Kragt and Holmes2021) and help understand what personal qualities support the readiness to be a volunteer and, as a result, tailor the recruitment processes in organizations and better predict which potential volunteers are most likely to engage and stay. During uncertain times – post-COVID-19 period and turbulent geopolitical climate, volunteers are a crucial workforce for numerous entities and beneficiaries (Purwanto & Rostiani, Reference Purwanto, Rostiani, Widyaningsih and Jati2023). Our research question is thus vital for science and the social life and practice of organizations that engage volunteers.

Prosocial Motivation Theory Overview

According to the prosocial motivation theory by Reykowski (Reykowski & Smoleńska, Reference Reykowski and Smoleńska1980; Reykowski, Reference Reykowski and Staub1984), there are three motivational pathways to acting prosocial: intrinsic, endocentric, and ipsocentric. The intrinsic motive describes the propensity to help out of care for other people’s welfare. For example, a person witnesses another’s distress and intends to relieve it. Therefore, the relief of other’s distress is the ultimate goal of prosocial activity. The endocentric motive focuses on acting prosocial out of a belief to obtain benefits for self-esteem, remaining congruent with what is important for ourselves (fulfilling a personal standard of helping), and maintaining a positive self-image. Finally, the ipsocentric motive describes the willingness to behave prosocial to maximize gains or avoid losses (Reykowski, Reference Reykowski and Staub1984). Empirical works of the Reykowski’s research team revealed that individuals may vary in the degree to which they are motivated by each of the paths, and different prosocial behaviors might be grounded in a variety of motivations (Karylowski, Reference Karylowski and Staub1984). Nevertheless, these motivational paths are considered distinct, and dependent on a person’s life experiences, personality organization (value system) and parental rearing behaviors (Kochanska, Reference Kochanska and Staub1984).

People differ in individual differences that can make them more or less inclined to act prosocial out of the abovementioned motivations. To identify them, we will refer below to other relevant lines of research on prosocial motivations. Below, we present each of the proposed individual differences to be tested concerning the three pathways identified by Reykowski (Reference Reykowski and Staub1984). We suggest that empathy is relevant to the intrinsic motives (Batson et al., Reference Batson, Lishner, Stocks, Schroeder and Graziano2015), satisfaction with and meaning in life – to the endocentric motives (Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Hosking, Burns and Anstey2019; Klein, Reference Klein2017), and social value orientation – to ipsocentric motives (as it is an individual difference describing selfishness versus altruism in the social exchange processes; Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Ackermann and Handgraaf2011).

Intrinsic Motive: Empathy

The intrinsic motive, in the language of the prosocial motivation theory by Reykowski, resembles the branch of research on prosocial acts, which concentrates on empathy as their antecedent (Batson et al., Reference Batson, Dyck, Brandt, Batson, Powell, McMaster and Griffitt1988). Empathy is the feeling of care for another person in response to witnessing their difficulties or lack of welfare (Batson et al., Reference Batson, Lishner, Stocks, Schroeder and Graziano2015). It activates emotions (Dovidio, Reference Dovidio1991) and impacts decision-making (Silfver et al., Reference Silfver, Helkama, Lönnqvist and Verkasalo2008).

According to the theory by Batson (Batson et al., Reference Batson, Lishner, Stocks, Schroeder and Graziano2015), the empathy-altruism hypothesis, empathy activates the altruistic motivation to help a person to whom empathy is felt. Helping occurs when it is considered possible, more positive than leaving another without support or having another person help. Moreover, helping brings rewards to the helper (such as positive emotions), the ultimate aim of helping is to relieve another person’s distress and increase their well-being.

Research evidence supports the idea that empathy can be linked to the length of experience in volunteering, time spent on it (Penner & Finkelstein, Reference Penner and Finkelstein1998), and positive expectations toward volunteering (Barraza, Reference Barraza2011; Davis et al., Reference Davis, Hall and Meyer2003). Moreover, a recent experimental study showed that inducing empathy was found to increase volunteering intentions for the future among non-volunteers, particularly those with low personal level of belief in a just world (Soyoren & Aktas, Reference Soyoren and Aktas2024), which shows the promising role of this individual difference for the willingness to commit to voluntary action. That is why we hypothesize that:

(H1) Empathy positively influences volunteering intentions over time.

Endocentric Motive: Satisfaction with and Meaning in Life

The endocentric motive of prosocial behaviors underlines the concerns about the self and staying congruent with its needs and values. The congruence with one’s needs might be the source of well-being (Sheldon & Elliot, Reference Sheldon and Elliot1999). Consequently, evidence suggests that volunteers improve their well-being due to their activities (Binder & Freytag, Reference Binder and Freytag2013; Meier & Stutzer, Reference Meier and Stutzer2008). Volunteers are also more satisfied with life than non-volunteers (Meier & Stutzer, Reference Meier and Stutzer2008). A study on older adults suggested that longer volunteering is also associated with higher life satisfaction over four years (Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Hosking, Burns and Anstey2019).

Similarly, research suggests a positive association between engagement in volunteering and meaning in life, which may be due to the increased sense of self-worth due to prosocial engagement (Klein, Reference Klein2017). Moreover, helping others enables volunteers to gain a social reputation and acceptance, resulting in a higher social status within communities (Flynn et al., Reference Flynn, Reagans, Amanatullah and Ames2006; Grant & Gino, Reference Grant and Gino2010). Social acceptance is crucial for self-esteem and self-worth, leading to a greater sense of meaning in life and life satisfaction.

We, therefore, argue that in the general population, satisfaction with life and meaning in life can facilitate the willingness to volunteer to sustain positive feelings and act in congruence with them. According to the volunteer process model (Clary et al., Reference Clary, Snyder, Ridge, Copeland, Stukas, Haugen and Miene1998), concerns regarding protecting the ego and boosting positive emotions are the antecedents of the decision to volunteer. That is why life satisfaction and meaning in life might be considered the endocentric pathway to volunteering intentions. We thus propose that:

(H2) Satisfaction with life and meaning in life positively influence volunteering intentions over time.

Ipsocentric Motive for Volunteering: Social Value Orientation

Ipsocentric motives of prosocial behaviors concentrate on balancing gains and losses due to these behaviors. It resembles the cost–benefit analyses in the prosocial behavior domain, as the decision whether to engage in helping or not is impacted by the balance between the donor’s investment and the perceived effect of the intervention (Franchin et al., Reference Franchin, Agnoli and Rubaltelli2023; Pittarello et al., Reference Pittarello, Caserotti and Rubaltelli2020).

People differ in how they tend to behave in social interactions to maximize their own or others’ gains (thus, behave competitively or altruistically). An individual difference that describes this propensity is social value orientation (Franchin et al., Reference Franchin, Agnoli and Rubaltelli2023; Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Ackermann and Handgraaf2011; Van Lange et al., Reference Van Lange, Bekkers, Schuyt and Vugt2007). Volunteering is a collaborative action that requires an orientation toward others rather than selfish behaviors (Gilbert et al., Reference Gilbert, Holdsworth and Kyle2017). It has been confirmed in research that showed that social value orientation is a predictor of charitable donations and voluntary participation in research (McClintock & Allison, Reference McClintock and Allison1989), as well as of volunteering intentions in a month, year, and three years (Nowakowska, Reference Nowakowska2024). Furthermore, volunteers display a higher social value orientation than non-volunteers (Nowakowska, Reference Nowakowska2022). That is why we hypothesize that:

(H3) Social value orientation positively influences volunteering intentions over time.

Following the three stated hypotheses, we intend to see which of motivational pathways are the strongest predictors of volunteering intentions over time. We also test whether volunteering intentions at time 1 shape any of these individual differences over time. Testing such effects is especially interesting as it may point to potential reciprocal effects, such as when intentions to volunteer affect motivations, which again influence subsequent volunteering intentions. Another question is whether those motivations influence one another. This would give some insight into indirect effects.

Method

Participants

The minimum sample size requested from the panel at time 1 (T1) of the study was N = 800, and at time 2 (T2) – N = 500. The panel recruited a quota sample of N = 977 participants for the first study wave, exceeding the minimum to secure the study from the adverse effects of potential unexpectedly high dropout rate. The recruitment was planned to ensure the sample’s representativeness in terms of gender, age, size of place of residence, and education level, based on the data from the official statistics office in Poland (Statistics Poland, 2021; percentages in the sample for each of these categories + / − 2% difference from the official statistical data).

In the second wave of the study, out of the initial sample, N = 566 people remained (response rate: 57.93%) and were taken into account in the presented longitudinal analysis. Two hundred eighty-six females (50.5%) and 280 males (49.5%) took part, age range 18–65, M age = 44.86; SDage = 12.47. Two hundred fifty-nine people lived in a village (45.8%), 135 (23.9%) in a town with up to 50,000 inhabitants, 29 (5.1%) in a town with between 50,001 and 100,000 inhabitants, 84 (14.8%) in a town with between 100,001 and 500,000 inhabitants, 59 (10.4%) in a town with over 500,000 inhabitants. Thirty-seven people (6.5%) had primary school education, 168 (29.7%) had vocational education, 194 (34.3%) finished high school, 44 (7.8%) had a Bachelor’s degree, and 123 (21.7%) had a Master’s degree. Only 27 (4.8%) of participants who completed both waves were engaged in volunteering at the time of the study.

Procedure

The study was questionnaire-based, anonymous, and performed online with assistance from one of the largest research panels in Poland – Reaktor Opinii™ and performed online. Both waves were designed in the same way. Only registered panelists were getting information about the opportunity to participate and became the study respondents. The first wave was conducted between the 4th and 10th of May 2022, and the second an approximate year afterward, between the 20th of April and the 4th of May 2023. All participants provided informed consent before filling out the survey. According to the research panel’s policy, participants who finished the survey received remuneration points that could be later exchanged into money (it can be sent to a personal bank account or donated directly to a charity). The < blinded > research ethics committee approved the study protocol and materials before conduction, approval number 75/2022.

Measures

Empathy was assessed using The Basic Empathy Scale for Adults (Carré et al., Reference Carré, Stefaniak, D’Ambrosio, Bensalah and Besche-Richard2013; Polish version: Dolistowski & Tanaś, Reference Dolistowski and Tanaś2020). The questionnaire comprises 20 items forming two subscales: Affective and Cognitive Empathy. Responses are marked on a Likert scale from 1 – strongly disagree to 5 – strongly agree. Subscales’ global results were calculated as means of relevant items. Cronbach’s α were: for Affective Empathy: .83 for both study waves, for Cognitive Empathy: .82 for the first wave, and .80 for the second wave.

Satisfaction with life was assessed using the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Diener et al., Reference Diener, Emmons, Larsen and Griffin1985; Polish version: Jankowski, Reference Jankowski2015). It is a unidimensional questionnaire consisting of 5 items. Responses are marked on a Likert scale from 1—strongly disagree to 7—strongly agree. The satisfaction index with life was calculated as the mean of all items. Cronbach’s α for both waves of the study was .91.

Meaning in life was measured with the Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ; Steger et al., Reference Steger, Frazier, Oishi and Kaler2006; Polish version: Kossakowska et al., Reference Kossakowska, Kwiatek and Stefaniak2013). It is a unidimensional questionnaire consisting of 10 items. Responses are marked on a Likert scale from 1—absolutely untrue to 7—absolutely true. The index of meaning in life was calculated as the mean of all items. Cronbach’s α was .90 for both waves of the study.

Social value orientation was measured with Social Value Orientation Slider Measure version A (Murphy & Ackermann, Reference Murphy and Ackermann2014; Polish instruction: Nowakowska, Reference Nowakowska2020). Participants are instructed to divide fictitious resources (points) between themselves and another (hypothetical) person – a game partner. The participants are asked to select the most preferred division of the points out of 9 options for each of the six games. The social value orientation is computed as an angle ranging from − 16.26 (utterly competitive) to 61.39 (utterly altruistic), based on a syntax written by Baumgartner (n/d; available on ryanomurphy.com website). There is also an option to classify participants into categories: competitive, individualistic, prosocial, and altruistic, based on cutoff points of the social value orientation angle.

Volunteering intentions were measured with a self-reported prediction of volunteering in a month, year, and two years. It was assessed with three direct questions: How probable is it for you to work as a volunteer: (1) in a month; (2) in a year; (3) in two years. Participants responded using a percentage scale (0–100%). A similar method was used in works by Maki and colleagues (Reference Maki, Dwyer and Snyder2016) and Nowakowska (Reference Nowakowska2024). In previous studies (Nowakowska, Reference Nowakowska2024), volunteering intentions in various time horizons correlated highly, suggesting that the particular observed variables could form a latent one, capturing a higher-order construct. Thus, in the longitudinal models, the volunteering intentions for each wave were treated as a latent variable consisting of the three items.

Analytic Strategy

In this study, the intrinsic pathway (latent Intrinsic) was measured by two subscales of empathy: cognitive and affective empathy (observed variables); the endocentric pathway (latent Endocentric) was indexed by two observed variables: meaning in life and satisfaction with life; ipsocentric motivation (Ipsocentric) was an observed variable measured with social value orientation (SVO) angle index of competitive-altruistic tendencies (in case of a single measure, it is possible to use items or parcels of items as indicators of the latent variable, but in case of SVO angle index, that procedure would not be applicable); and volunteering intentions (Volunteering) were measured by 3 observed variables representing intentions to volunteer in a month (VolM), in a year (Vol1Y), and 2 years (Vol2Y). The structural model specified the relationships between latent variables regarding path analyses.

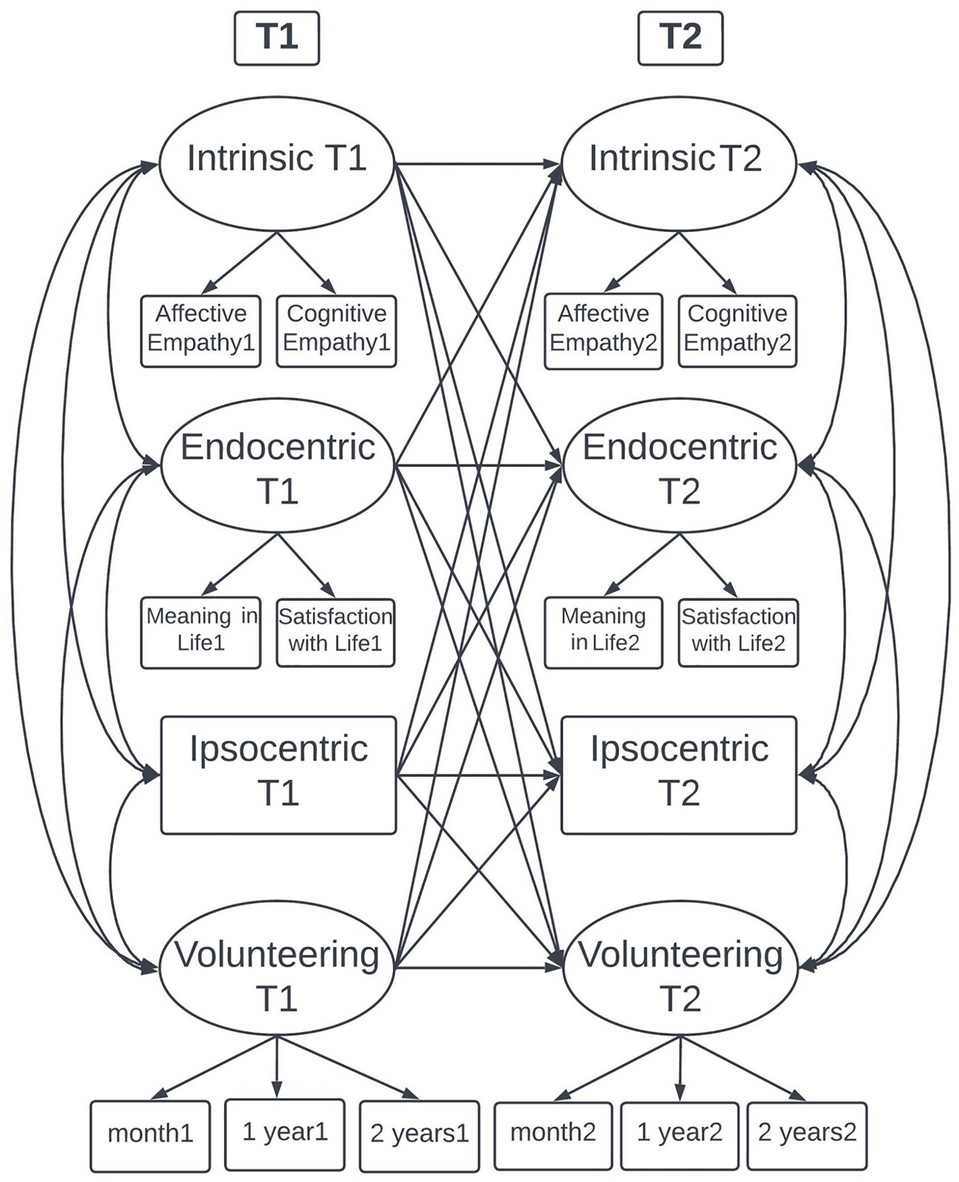

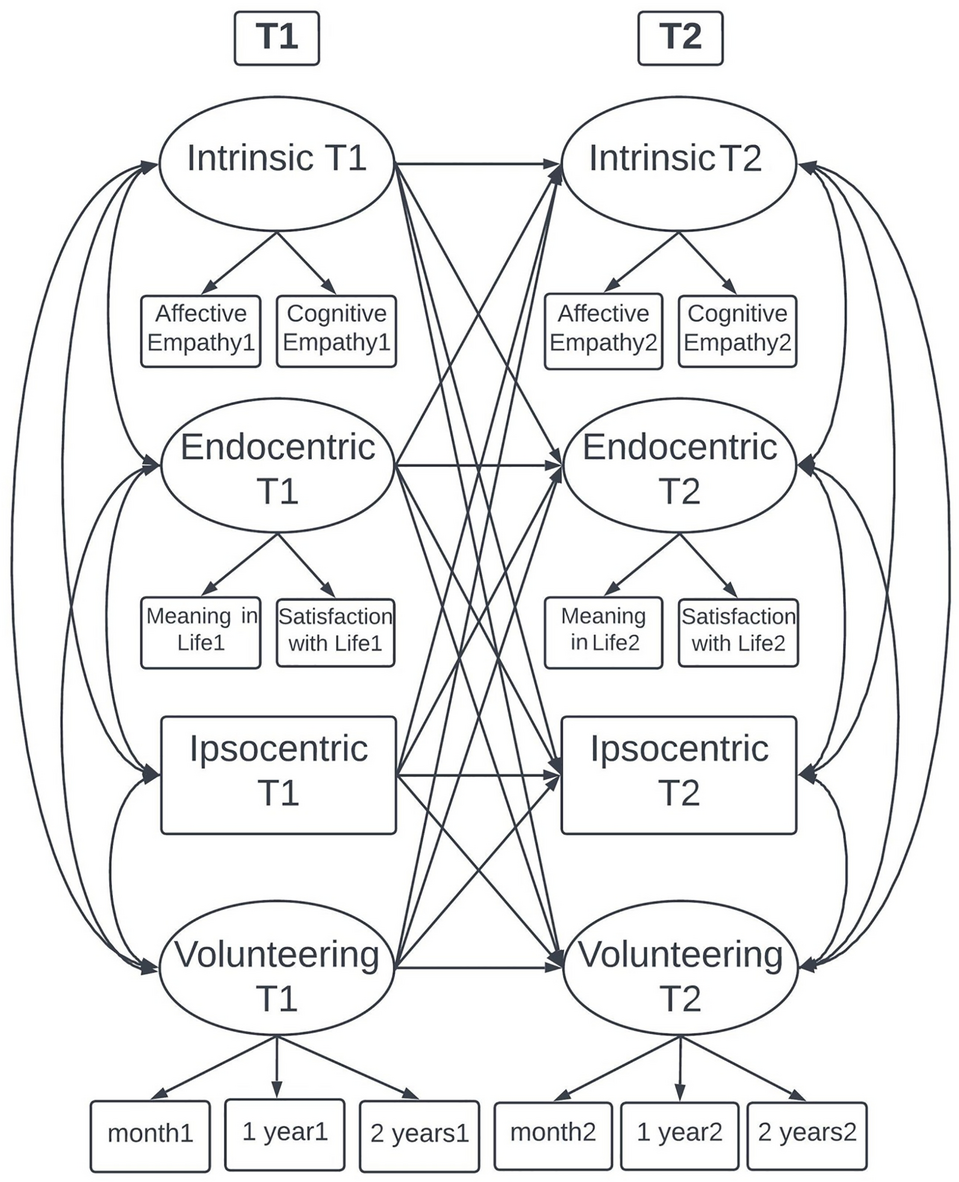

First, we conducted descriptive and correlational analysis with observed variables, testing for gender differences and variance in study variables related to the size of the place of residence and education. Second, we tested for the differences in observed variables between time 1 and 2 using paired-samples t-tests. We also conducted the abovementioned analysis with indices of two motivation types and general volunteering intentions created by averaging affective and cognitive empathy scales (Intrinsic), meaning in life and satisfaction with life (Endocentric), and volunteering intentions in a month, year, and 2 years (Volunteering). Third, we verified the hypothesis regarding the longitudinal relationships between the three types of pathways to volunteering (intrinsic, endocentric, ipsocentric) and volunteering intentions using a structural equation modeling (SEM with Maximum Likelihood method) of latent cross-lagged panel model with two-time points in AMOS. Figure 1 displays the measurement model without error variables. The measurement model defines how observed variables measure the latent variables.

Fig. 1 Theoretical cross-lagged panel model of prosocial motivations and volunteering intentions

The autoregressive effects provided information about the stability of a construct by representing the relation of the same construct between two waves. The model also included the within-time correlations to account for situation-specific effects by correlating the latent variables within each wave. Finally, the cross-lagged effects were specified, representing the effects of time1 on time 2. We used the goodness-of-fit indices to evaluate the model fit: CFI and NFI > .95, RMSEA < .06 (Hu & Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1999).

Results

Preliminary Analysis

First, we performed panel attrition analysis, results of which are described in Supplementary Material. Next, we tested whether measures were related to demographic variables among participants who completed both waves. Analysis of variance indicated no significant differences in study variables related to current place of residence. However, level of education, gender, and age were related to study variables. Pearson’s r correlation coefficients for demographic and study variables are presented in Supplementary Material Table S1.

In particular, women were higher than men on intrinsic motivation, volunteering intentions (T1 and T2), and ipsocentric motivation (T1). Older participants were characterized by more intrinsic motivation (T1 and T2) and cognitive empathy. Also, age was positively related to endocentric motivation (T1 and T2; only meaning in life). Education level was associated positively with intrinsic motivation (only cognitive empathy) and more volunteering intentions (T1 and T2) and endocentric motivation (T2). The measurement model was supplemented with those demographic variables in light of those results.

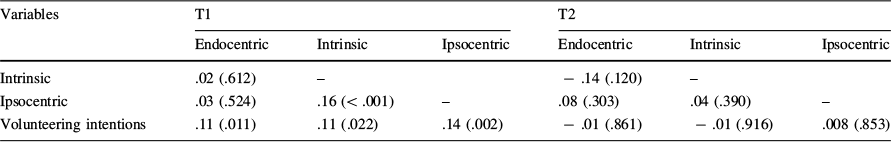

Zero-order Pearson’s correlation analysis indicated that observed variables within latent constructs were: for endocentric motivation .54 at T1 and .50 at T2, and for intrinsic motivation .51 at T1 and .44 at T2. Within T1 and T2, endocentric motivation was positively related to intrinsic motivation. Moreover, at T1, intrinsic and ipsocentric motivations were positively associated. Volunteering intentions were positively associated with all types of examined motivations. Correlation coefficients between study variables at T1 and T2 are presented in Supplementary Material Table S2.

Further results showed that motivation constructs remained stable over time, but volunteering intentions decreased from T1 to T2, even though the volunteering intention variables were correlated. Means and t-tests’ results are presented in Supplementary Material Table S3.

Cross-Lagged Panel Model

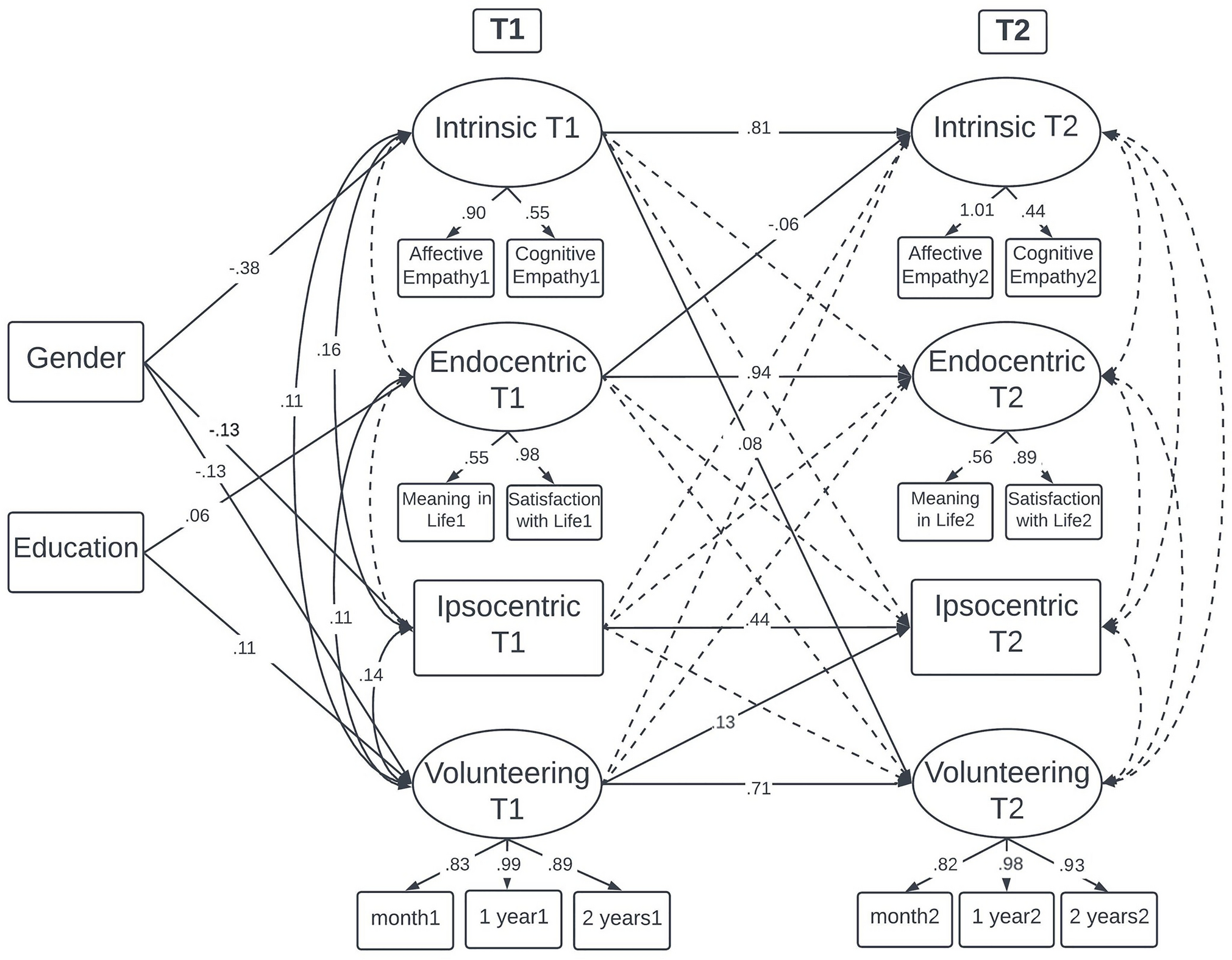

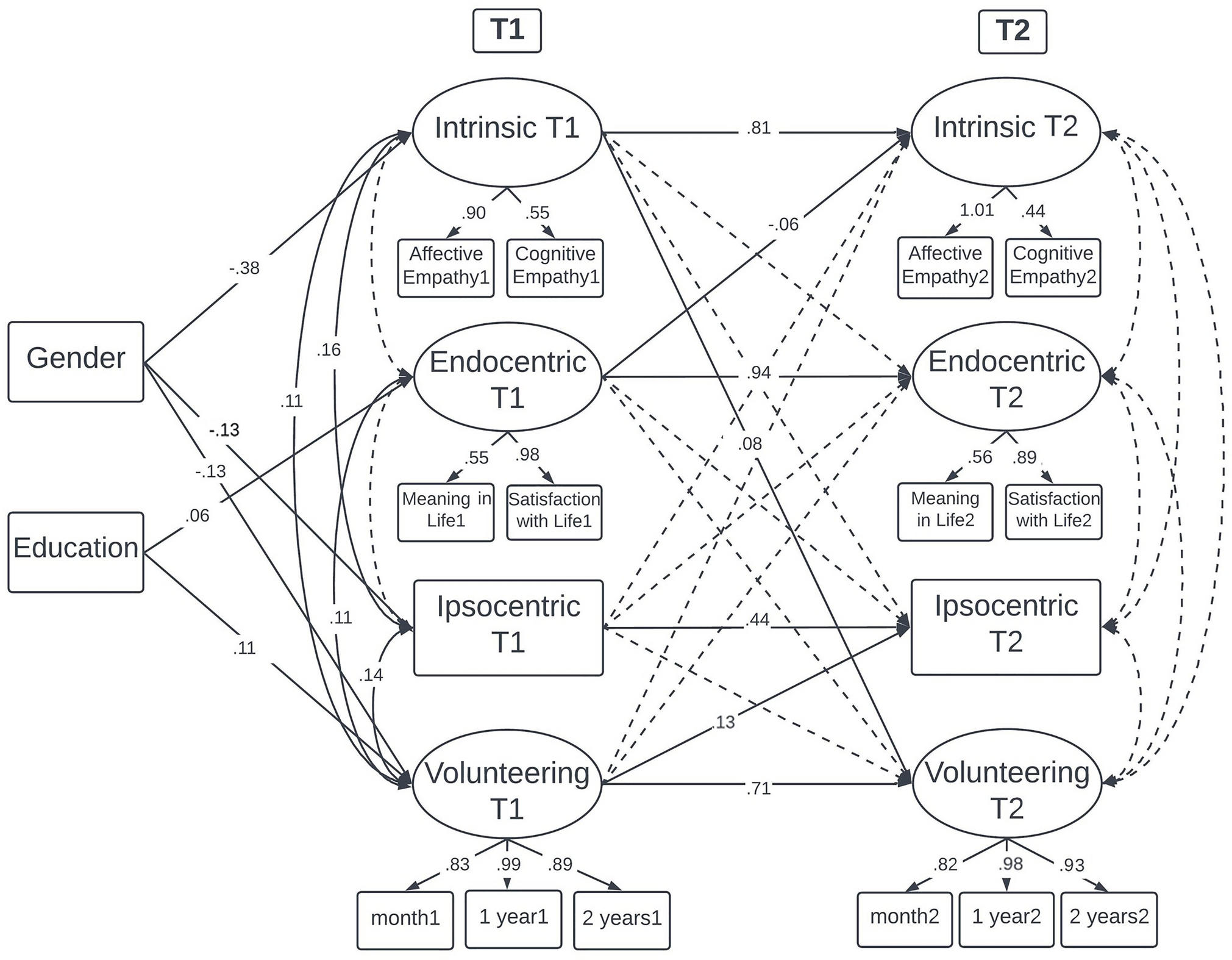

An overview of the significant standardized effects of the cross-lagged panel model is provided in Fig. 2. Dotted lines represent insignificant paths and relationships and solid lines represent significant relationships. Standardized effects are presented only for significant effects and relationships.

Fig. 2 Final empirical cross-lagged panel model of prosocial motivations and volunteering intentions supplemented with demographic predictors: age and education level

The model included auxiliary variables (Enders, Reference Enders2022), gender, age and education as predictors of all T1 variables, but only significant paths were left in the model (Spirtes et al., Reference Spirtes, Richardson, Meek, Scheines and Glymour1998; Sarstedt et al., Reference Sarstedt, Sarstedt, Ringle and Ringle2020). Education level was coded as not having higher education (coded 0, N = 399) vs. having higher education level (coded 1, N = 167), because participants who graduated from high school did not differ from those with lower education level in volunteering intentions at T1 (p = .359) and T2 (p = .060). Yet, those participants who did not graduate from high school differed in volunteering intentions from those who obtained Bachelor’s or higher degrees (p < .029). Gender was coded: 0 – women, 1 – men.

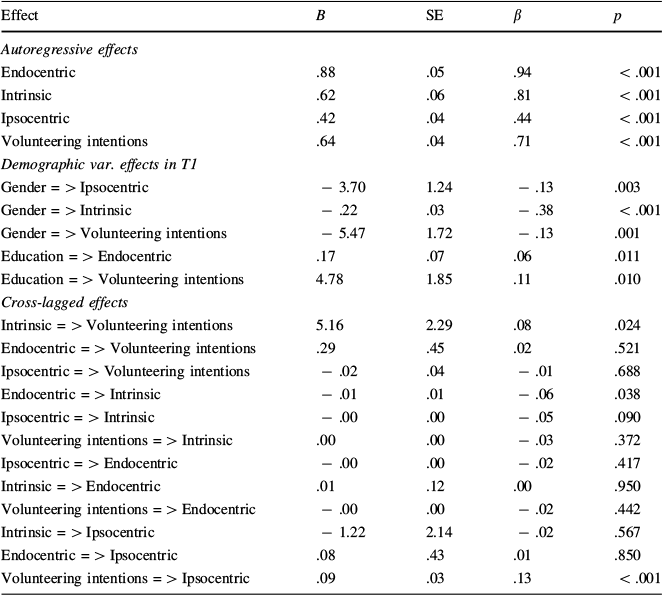

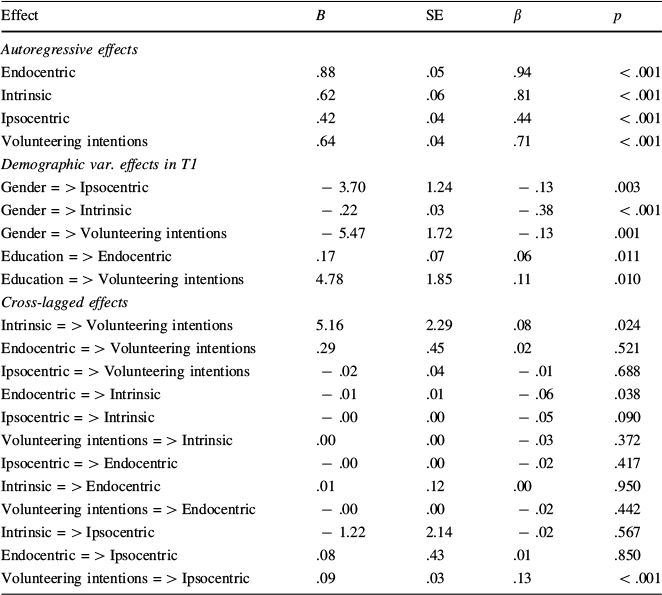

Age was dropped from the final solution as it was not a significant predictor of T1 variables. Table 1 shows the unstandardized and standardized effects of latent predictors, and Table 2 shows correlations in the model. Standardized loadings for indicator variables across time and correlations between error terms for indicators are provided in the Supplementary Material Table S4 and S5. The tested model was well adjusted to the data (χ 2 (101) = 277.28, p < .001; NFI = .956; CFI = .971; RMSEA = .056).

Table 1 Standardized and non-standardized autoregressive effects, T1 demographic variables effects on latent variables and cross-lagged effects between T1 and T2 motivations and volunteering intentions

|

Effect |

B |

SE |

β |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Autoregressive effects |

||||

|

Endocentric |

.88 |

.05 |

.94 |

< .001 |

|

Intrinsic |

.62 |

.06 |

.81 |

< .001 |

|

Ipsocentric |

.42 |

.04 |

.44 |

< .001 |

|

Volunteering intentions |

.64 |

.04 |

.71 |

< .001 |

|

Demographic var. effects in T1 |

||||

|

Gender = > Ipsocentric |

− 3.70 |

1.24 |

− .13 |

.003 |

|

Gender = > Intrinsic |

− .22 |

.03 |

− .38 |

< .001 |

|

Gender = > Volunteering intentions |

− 5.47 |

1.72 |

− .13 |

.001 |

|

Education = > Endocentric |

.17 |

.07 |

.06 |

.011 |

|

Education = > Volunteering intentions |

4.78 |

1.85 |

.11 |

.010 |

|

Cross-lagged effects |

||||

|

Intrinsic = > Volunteering intentions |

5.16 |

2.29 |

.08 |

.024 |

|

Endocentric = > Volunteering intentions |

.29 |

.45 |

.02 |

.521 |

|

Ipsocentric = > Volunteering intentions |

− .02 |

.04 |

− .01 |

.688 |

|

Endocentric = > Intrinsic |

− .01 |

.01 |

− .06 |

.038 |

|

Ipsocentric = > Intrinsic |

− .00 |

.00 |

− .05 |

.090 |

|

Volunteering intentions = > Intrinsic |

.00 |

.00 |

− .03 |

.372 |

|

Ipsocentric = > Endocentric |

− .00 |

.00 |

− .02 |

.417 |

|

Intrinsic = > Endocentric |

.01 |

.12 |

.00 |

.950 |

|

Volunteering intentions = > Endocentric |

− .00 |

.00 |

− .02 |

.442 |

|

Intrinsic = > Ipsocentric |

− 1.22 |

2.14 |

− .02 |

.567 |

|

Endocentric = > Ipsocentric |

.08 |

.43 |

.01 |

.850 |

|

Volunteering intentions = > Ipsocentric |

.09 |

.03 |

.13 |

< .001 |

Explained variance of T2 variables: volunteering intentions 53.2%, Endocentric motivation 89.0%, Intrinsic motivation 63.8%, Ipsocentric motivation 22.1%; gender coded 0 – women, 1 – men; education coded 0 – high school and lower, 1 – higher education level completed (Bachelor’s degree and higher)

Table 2 Correlations between residuals of the latent variables at T1 and T2. Significance in parenthesis

|

Variables |

T1 |

T2 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Endocentric |

Intrinsic |

Ipsocentric |

Endocentric |

Intrinsic |

Ipsocentric |

|

|

Intrinsic |

.02 (.612) |

– |

− .14 (.120) |

– |

||

|

Ipsocentric |

.03 (.524) |

.16 (< .001) |

– |

.08 (.303) |

.04 (.390) |

– |

|

Volunteering intentions |

.11 (.011) |

.11 (.022) |

.14 (.002) |

− .01 (.861) |

− .01 (.916) |

.008 (.853) |

Autoregressive Effects

All autoregressive effects were significant and positive, ranging from .44 for ipsocentric motivation/social value orientation to .94 for endocentric motivation. The results indicate high temporal stability of the constructs.

Demographic Variables’ Effect on Time 1 Measures

Results showed that women scored higher than men on intrinsic and ipsocentric motivation and volunteering intentions, but gender was unrelated to endocentric motivation. Moreover, higher education was associated with more endocentric motivation and volunteering intentions.

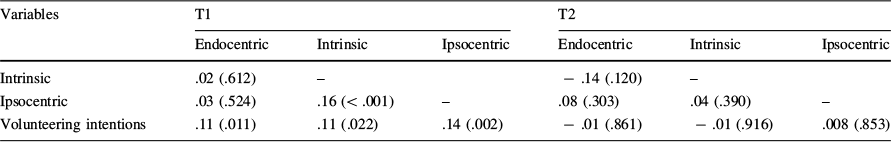

Within-Time Correlations – Stability of Relationships between Variables Over Time

Results of the within-time correlations between constructs at T1 indicated significant and positive but weak relationships between all motivations and volunteering intentions. However, those within-time specific effects were no longer significant at T2, indicating that mostly autoregressive and cross-lagged effects were responsible for T2 volunteering. Additionally, in time 1, only intrinsic and ipsocentric motivation were correlated, whereas endocentric motivation was unrelated to the other two motivations. Zero-order correlations showed different patterns of results (endocentric and intrinsic motivations were related, but ipsocentric motivation was associated only with intrinsic motivations at T1). In time 2, motivations were not associated.

Cross-Lagged Effects and Hypothesis Testing

Only 3 of the 12 paths were significant. Intrinsic motivation at T1 was positively but weakly associated with subsequent volunteering intentions (β = .08; p < .05). T1 volunteering intentions also positively predicted later ipsocentric motivation (β = .13; p < .001). Additionally, endocentric motivation at T1 was negatively related to following intrinsic motivation (β = − .06; p < .05).

Discussion

Despite within-time correlation patterns congruent with the predictions about three potential pathways leading to volunteering intentions over time, the results of structural equation modeling indicated that only empathy (intrinsic path for prosociality) predicted volunteering intentions over time. This result confirms H1. The effect over time was not observed for satisfaction with life and meaning in life (endocentric path), nor for social value orientation (ipsocentric path), contrary to H2 and H3.

Our result regarding empathy is consistent with the theoretical suggestions about its crucial role in motivating prosocial behavior (empathy-altruism hypothesis; Batson et al., Reference Batson, Lishner, Stocks, Schroeder and Graziano2015) and empirical data showing it is one of the most essential traits for volunteering (Mitani, Reference Mitani2014). In previous studies, empathy was also found to motivate voluntary action and sustain the activity, given that volunteers can make sense of the emotions they feel through engagement (Doidge & Sandri, Reference Doidge and Sandri2019). Our result provides an additional insight into how people from the general population sustain their willingness to become volunteers over time thanks to empathy, and highlights that empathy could be targeted when encouraging people to join voluntary action initiatives.

Despite the positive cross-sectional correlation between satisfaction with and meaning in life (endocentric path) and volunteering intentions, which aligns with the literature (Klein, Reference Klein2017; Meier & Stutzer, Reference Meier and Stutzer2008), this path did not predict volunteering intentions over time. Thus, people with positive views on life might have the resources to help here and now, but the positive outlook is not the causal element of helping intentions. Instead, it only accompanies them. Noteworthy, satisfaction with life and meaning in life do not bring a propensity to help others per se, which could be why they predict volunteering behaviors weaker and less stable than empathy. Furthermore, some studies suggest that prosocial behavior is an antecedent of satisfaction with life rather than vice versa (Baranik & Eby, Reference Baranik and Eby2016). Our study did not assess actual behaviors but intentions for them, which did not allow us to replicate this result. Nevertheless, it is an exciting research avenue for further studies.

Noteworthy, endocentric individual differences predicted lower intrinsic individual differences (empathy) a year afterward. Interpreting this phenomenon alongside the abovementioned mechanisms regarding the endocentric path, we observe that satisfaction with and meaning in life can indirectly decrease volunteering intentions over time. This is because it negatively influences empathy, and lower empathy causes lower volunteering intentions. Moreover, despite the result being contrary to the cross-sectional evidence suggesting a positive relationship between satisfaction with life and empathy (Totan & Sahin, Reference Totan and Sahin2015) and meaning in life and empathy (Damiano et al., Reference Damiano, de Andrade Ribeiro, Dos Santos, Da Silva and Lucchetti2017), it fits the previous findings regarding how people who experienced life adversity may further display more empathy towards others, given that they understand the difficulties others may face (Frazier et al., Reference Frazier, Conlon, Steger, Tashiro, Glaser and Columbus2006). Moreover, people with depressive symptoms (thus, typically of lower satisfaction with life; Saunders & Roy, Reference Saunders and Roy1999) are reported to have normal or elevated empathy (O’Connor et al., Reference O’Connor, Berry, Lewis, Mulherin, Crisostomo, Farrow and Woodruff2007), which also resembles our result. Noteworthy, it is possible that throughout the year of the study, the participants experienced some life events which we did not capture in our study (e.g., increased job or parental burnout due to the change from pandemic regulations in 2022 to coming back to normality in 2023, other changes in life circumstances, mental health adversities) that could moderate the relationship between satisfaction with life/meaning in life and empathy.

For the ipsocentric path, although social value orientation did not predict volunteering intentions in the second measurement, volunteering intentions predicted social value orientation in the second measurement. Presumably, this pathway is due to the fact that volunteering is a specific form of cooperation (Hillenbrand & Winter, Reference Hillenbrand and Winter2018). People who intended to volunteer and did so throughout the following year might have realized their need to cooperate and developed the propensity to do so (as volunteering may help in that; Khasanzyanova, Reference Khasanzyanova2017). At the same time, those participants who did not volunteer in the year following time 1 measurement could have expressed their need to engage for others in a generally heightened propensity to share with others (as the SVO Slider Measure measures it). Our result shows that volunteering can be promising in building prosocial attitudes and is thus an activity worth promoting in the general population, which is in line with findings by Wilson and Musick (Reference Wilson and Musick1999).

Moreover, some interesting data on the role of demographics for volunteering intentions emerged from our analysis. Women were higher on intrinsic (empathy) and ipsocentric (social value orientation; only at T1) individual differences, as well as volunteering intentions. It is in line with previous research, given that in self-report measures, women tend to appear more empathetic than men (Löffler & Greitemeyer, Reference Löffler and Greitemeyer2023). Furthermore, women tend to score higher than men in measures of social value orientation angle (Grosch & Rau, Reference Grosch and Rau2017). However, the results available for volunteering intentions and gender are mixed across countries (for an overview, see Wiepking et al., Reference Wiepking, Einolf and Yang2023), whereas our study provides data supporting the idea that women are more inclined to volunteer.

Education was positively related to satisfaction with and meaning in life. It is in line with results that suggest that education influences job, financial, and health satisfaction, independently contributing to general life satisfaction (Ilies et al., Reference Ilies, Yao, Curseu and Liang2019). Moreover, education was related to higher volunteering intentions. The reason behind it might be that education causes a greater need to use a person’s skills and contributes to having more contacts and skills needed to search for volunteering opportunities (Griffin & Hasketh, Reference Griffin and Hesketh2008).

Practical Implications

According to our study, empathy is the factor that predicts the sustained intentions of the general population to volunteer in the future. Thus, especially when the volunteering tasks involve long-term commitment, it is worthwhile to recruit empathetic candidates who are likely keen to remain active for longer. Previous research suggests candidates for volunteering to fill out empathy measures as part of their recruitment and placement process (Egbert & Parrott, Reference Egbert and Parrott2003). Thanks to this, the organization can better predict and prevent volunteer dropout, or fit the activities better to the candidate’s dispositions. Furthermore, a promising avenue for encouraging people to become civically active are approaches related to developing mentalization skills in the community (among potential volunteers), as mentalizing is closely related to cognitive empathy and is a skill of correctly inferring about others’ inner states (Lehmann et al., Reference Lehmann, Böckler, Klimecki, Müller-Liebmann and Kanske2022).

When volunteers are already recruited, it could be helpful to maintain an empathetic climate of collaboration within organizations by offering workshops and events (for example, integrating volunteers or donors) or facilitating feedback on tasks from the beneficiaries. Similar to guidelines provided by researchers regarding medical professionals (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Blakely, Daugherty, Kiersma, Meny and Pereira2024), forming meaningful connections within the organization, e.g., through mentorship, positive role modelling an reflexive practice could possibly enhance empathy in volunteers.

Moreover, the study indicates that volunteering intentions may shape social value orientation over time. It shows that participation in voluntary action might help develop a more other-oriented attitude in prosocial sharing contexts, and therefore, could be a valuable experience to be gained by people in the general community. Volunteering experiences, thanks to their potential in forming altruistic attitude, could be very valuable for individuals who pursue a career in compassion-based professions. Moreover, as cooperative tendencies are highly valuable in volunteering settings, it is advisable to engage people in collaborative projects and tasks to facilitate the development of this propensity.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Despite its longitudinal nature and innovative theoretical approach to investigating volunteering intentions in the general population, our study has limitations. First, the representativeness of the final sample considered in the analyses was compromised by participant dropout. Additionally, since our study was conducted online and advertised only among registered users of a specific research panel, the scope of people who had access to the survey was limited, which could impact the generalizability of our results to populations less familiar with digital tools. Participants were given points that could be exchanged for money and transferred to a personal bank account or charity of their choice. However, participants could only receive the reward after accumulating points from several surveys. This may have resulted in some participants filling out the survey primarily for external reasons and inattentively. Nevertheless, our analysis indicated that the measurement was reliable, with a satisfactory Cronbach’s α. Thus, these motivational effects can be considered negligible.

The study was also conducted at a specific time. The first wave was conducted two months after the outbreak of war in Ukraine, a neighboring country of Poland. This event triggered the mobilization of Polish society to help refugees (Byrska, Reference Byrska2023). Unfortunately, we do not have data from before or during the pandemic, which could have deepened our understanding of the dynamics of volunteering intentions over time. Additionally, we only considered declarations about future volunteering among individuals with no prior experience. We only controlled for current volunteering, which revealed that less than 5% of the sample was engaged in it. We did not control for past involvement, which might be important for future intentions to undertake this activity.

Moreover, despite empathy emerged as the most prominent predictor of volunteering intentions over time, the effect was relatively weak. This might suggest the limitation of using Reykowski’s theory in the specific context of volunteering intentions. In future studies, the usage of different theoretical frameworks (e.g., self-determination theory, social exchange theory, evolutionary theories), and taking into account situational or contextual factors of involvement in volunteering (e.g., personal adversities, access to volunteering opportunities, caring responsibilities, opinions about volunteering in general, and other aspects) is advisable. Such approach might deepen the understanding whether empathy is a consistent predictor of volunteering intentions and/or under what circumstances it might not be such.

Furthermore, it is advisable to continue longitudinal investigations, encompass other relevant variables, and go beyond research panel users, maintaining the sample’s representativeness for the population of interest. Furthermore, future research could explore the role of volunteering intentions and actual volunteering activity in shaping social value orientation (thus, cooperative tendencies) to understand better the impact of volunteering on decision-making processes in social interactions.

Conclusion

Our study examined volunteering intentions through the lens of prosocial motivation theory and empirical data on pathways to prosociality. Our analysis revealed that empathy, or intrinsic prosocial motivation, measured at the first wave of the study predicted subsequent volunteering intentions one year later. However, other potential pathways (endocentric, related to life satisfaction or meaning in life; and ipsocentric, related to social value orientation) did not predict subsequent volunteering intentions. These results suggest that concern for the well-being of others is the strongest factor associated with volunteering intentions in the general population. This shows that empathetic people are more likely to engage in voluntary behaviors over a prolonged period. Furthermore, volunteering intentions at time 1 predicted social value orientation at time 2. This suggests that volunteering can effectively foster positive prosocial attitudes and is therefore a worthwhile activity to promote in the general population.

Author’s contribution

Iwona Nowakowska: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing-original draft, Writing—review and editing, Project administration. Joanna Rajchert: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing.

Funding

The study was supported by National Science Centre, Poland PRELUDIUM grant 2021/41/N/HS6/01312.

Data availability

The underlying data can be found on Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/se6tg/.

Declarations

Ethical approval

The study protocol and materials were approved by Maria Grzegorzewska University Research Ethics Committee, approval number 75/2022.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.