Advances in early detection, treatment and supportive care in cancer have led to significant improvements in survival, contributing to a growing global population of cancer survivors. An estimated 50 million people were living after a cancer diagnosis in 2020, a figure expected to rise further in the coming decades(1). Five-year survival now exceeds 85–90% for breast cancer in several high-income countries(2), while cervical cancer survival surpasses 70% in Japan, Norway and South Korea(3). However, increased survival is accompanied by a substantial burden of late and long-term effects, including fatigue, psychosocial challenges, CVD, metabolic dysfunction, osteoporosis and impaired physical functioning(Reference Egger-Heidrich, Wolters and Frick4–Reference Soldato, Arecco and Agostinetto6).

Survivors, therefore, face complex, ongoing physical, metabolic and psychosocial challenges beyond acute care that significantly affect their nutritional status and overall health(Reference Bergerot, Bergerot and Philip7). Nutrition plays an important role in influencing long-term health, recurrence risk and quality of life (QoL) among cancer survivors and is one of the few modifiable factors that can prevent or delay the early onset of chronic diseases. Better dietary quality has been correlated with lower overall mortality rates in cancer survivors(Reference Park, Kang and Shvetsov8). However, compared to individuals without a history of cancer, survivors often report poorer nutritional intake, increasing the risk of malnutrition(Reference Zhang, Liu and John9).

Despite this, nutrition remains insufficiently embedded within survivorship pathways. Cancer survivors frequently report unmet nutritional needs and limited access to credible, practical guidance(Reference O’Callaghan, Douglas and Keaver10–Reference Keaver, Richmond and Rafferty15). Healthcare professionals cite low confidence, inconsistent resources, limited time and restricted referral pathways as barriers to providing nutritional support(Reference Keaver, Richmond and Rafferty15–Reference Scott and Hoskin17). As a result, opportunities to promote long-term health and prevent avoidable morbidity are often missed.

This review examines current evidence and practice on integrating nutrition into survivorship care and proposes a tiered model of nutrition support to enable accessible, equitable and evidence-based care for all cancer survivors. There is no universal definition of cancer survivorship, with interpretations varying across countries and health systems. For this review, survivorship refers to the post-treatment period, when care transitions from active treatment to long-term recovery, self-management and optimisation of health and QoL(Reference O’Connor, O’Donovan and Drummond18).

Exploring the evidence

Dietary challenges

Children and adolescents

Despite the central role of diet in long-term health, evidence consistently shows that children and adolescent cancer survivors exhibit poor diet quality and nutrient inadequacy.. Energy intake is often imbalanced; some survivors exceed requirements, while others consume insufficient energy(Reference Cohen, Wakefield and Fleming19–Reference Landy, Lipsitz and Kurtz21). Macronutrient distribution is frequently suboptimal, with excessive total fat and sodium intakes and limited fibre and complex carbohydrate consumption(Reference Murphy-Alford, White and Lockwood22). Studies commonly report moderate adherence to dietary guidelines, reflected in mean Healthy Eating Index scores of 50–57(Reference Landy, Lipsitz and Kurtz21,Reference Zhang, Saltzman and Kelly23,Reference Belle, Chatelan and Kasteler24) . Notably, these scroes are similar to those reported in the general American adolescent population, underscoring that although survivors’ diets mirror broader population trends, they remain nutritionally inadequate for a group at heightened risk of chronic disease and who experience the onset of chronic health conditions far earlier in life(Reference Acar Tek, Yildiran and Akbulut25).

Micronutrient inadequacy is widespread and persists for many years post-treatment. Across multiple cohorts, 30–68% of survivors exhibit inadequate calcium intake, and up to 95% are deficient in vitamin D, increasing the risk of early-onset osteoporosis(Reference Zhang, Liu and John9,Reference Cohen, Wakefield and Fleming19) . Folate insufficiency is reported in up to 60% of survivors and may elevate cardiovascular risk(Reference Barr and Stevens26). Deficiencies in vitamins B6, B12 and E, along with minerals such as Mg, Se, iodine and Fe, have implications for immune function, growth and cognitive development(Reference Shams-White, Kelly and Gilhooly27).

Overall dietary patterns are characterised by low intake of fruit, vegetables, whole grains and plant-based proteins, alongside high consumption of saturated fat, sodium and processed foods(Reference Belle, Chatelan and Kasteler28,Reference Badr, Chandra and Paxton29) . These trends persist regardless of geography, socio-economic status or time since treatment. Behavioural and psychosocial factors, including emotional overeating, picky eating and treatment-related changes in taste and smell, further contribute to dietary imbalance(Reference Hansen, Stancel and Klesges30–Reference Marchak, Kegler and Meacham32).

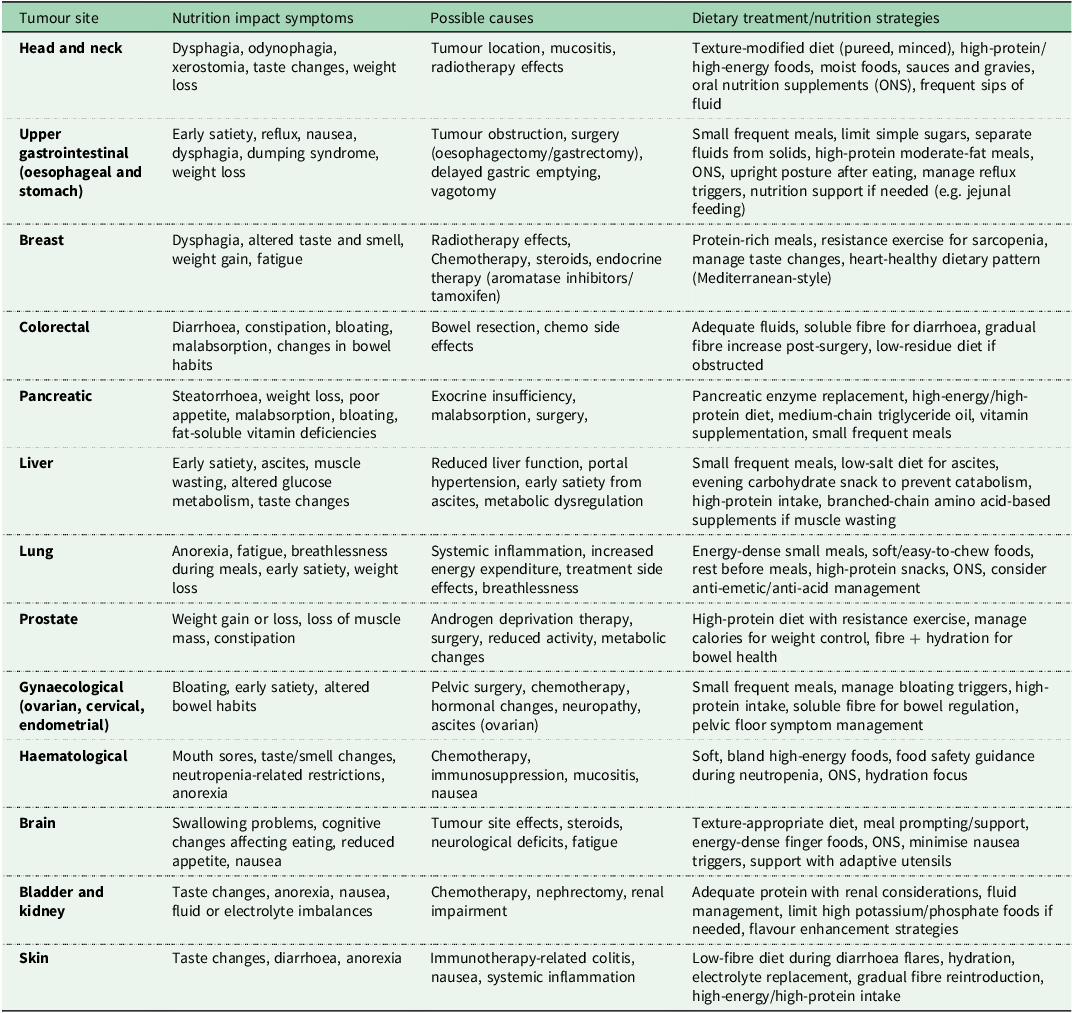

Understanding behavioural determinants of diet quality among childhood and adolescent cancer survivors is crucial. Treatment side effects, such as nausea, fatigue and altered taste, can create persistent food aversions and reduced dietary diversity(Reference Shams-White, Kelly and Gilhooly27) (see Table 1 for a detailed outline of nutrition impact symptoms by cancer type and practical management strategies for each). Fleming et al.(Reference Fleming, Murphy-Alford and Cohen31) found significantly lower diet quality scores (mean 32.3 v. 34.8; P = 0.028) and higher parent-reported rates of picky eating and emotional overeating than controls. Hansen et al. (Reference Hansen, Stancel and Klesges30) also reported increased emotional eating in female adolescent survivors, particularly among those further from treatment.

Table 1. Nutrition impact on symptoms experienced by cancer type

Data sourced from ESPEN guidelines(Reference Kenkhuis, Vlooswijk and Janssen75), the Irish Cancer Society Diet and Nutrition booklet(135) and HEAL Well: A Cancer Nutrition Guide was created through a joint project of the American Institute for Cancer Research, the LIVESTRONG Foundation and Savor Health(136).

Adults

Adult cancer survivors, including adult survivors of childhood cancers, young adults (18–39), middle-aged adults (40–65) and older adults (65+), represent a diverse group whose nutrition needs and challenges evolve with age and treatment exposure.

In comparison to the general population, lower intakes of fruit and vegetables and a poorer dietary quality have been reported among adult cancer survivors(Reference Zhang, Liu and John33). Persistent treatment-related symptoms such as fatigue, altered taste and smell, gastrointestinal disturbances, pain, iatrogenic menopause and emotional distress frequently continue well into survivorship, directly influencing food preferences, intake and metabolic outcomes (Table 1). These symptoms can lead to poor appetite, unintentional weight loss or, in some cases, weight gain, compounding long-term impairments in QoL and functional status. Nutrition impact symptoms (NIS), including fatigue, taste and smell changes, nausea, mucositis and dysphagia, compromise dietary intake, nutrient absorption and nutritional status(Reference Crowder, Douglas and Pepino34). Chronic NIS are highly prevalent among head and neck cancer survivors post-chemoradiotherapy, with dysphagia affecting 15–79% of survivors, xerostomia up to 90% at 12 months and reliance on soft or pureed diets reported in up to 74%(Reference Crowder, Douglas and Pepino34). These limitations significantly affect psychosocial well-being, including social avoidance and fear of eating in public. Long-term impairments can persist 5–10 years post-treatment(Reference Crowder, Douglas and Pepino34–Reference Tan, Turner and Kerin-Ayres36).

Chemotherapy-induced amenorrhoea and premature ovarian insufficiency are common, with rates of 15–94% depending on treatment regimen, age and follow-up(Reference Wang, Li and Liang37). High-risk cyclophosphamide-based regimens can induce ovarian failure in >80% of older premenopausal women(Reference Mauri, Gazouli and Zarkavelis38), while ≥50% of women aged ≥40 years experience permanent menopause(Reference Mar Fan, Houédé-Tchen and Chemerynsky39,Reference Zhang, Wu and Zheng40) . Iatrogenic menopause is often abrupt and symptomatic, contributing to metabolic dysfunction, adverse body composition changes and altered appetite regulation.

Socio-economic factors further compound these challenges. Financial toxicity exacerbates dietary compromise, reduces muscle mass and increases long-term risk of malnutrition, poorer QoL and mortality(Reference Carrera, Kantarjian and Blinder41). Collectively, persistent treatment-related symptoms, NIS, psychosocial factors and socio-economic barriers interact to compromise dietary intake, nutritional status and long-term survivorship outcomes.

Long-term health implications

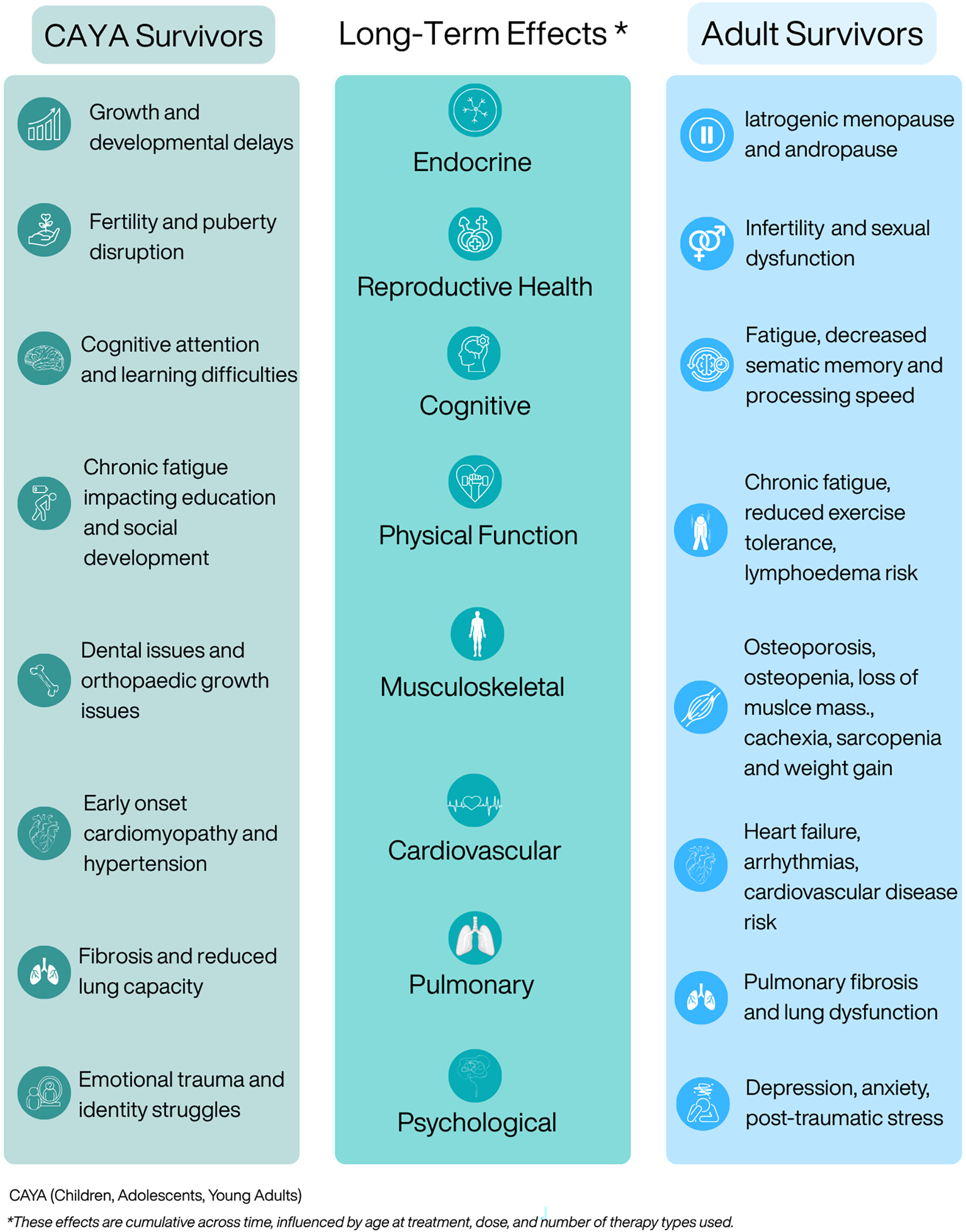

Advances in cancer treatment have markedly improved survival but have also increased the number of people living with long-term health consequences. These late effects, which can appear months or years after treatment, affect multiple organ systems, including cardiovascular, endocrine, musculoskeletal, neurocognitive and psychosocial domains (Figure 1), and vary by diagnosis, treatment exposure and individual susceptibility(Reference Landier, Armenian and Bhatia42,Reference Erdmann, Frederiksen and Bonaventure43) . Comorbidity presence and severity are strong predictors of early mortality in survivors(Reference Leach, Weaver and Aziz44).

Figure 1. Late and long-term effects of cancer treatment across the lifespan.

Large population-based cohorts over the past four decades have elucidated the long-term physical and metabolic effects of childhood cancer survival(Reference Bhatia, Armenian and Armstrong45). The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS; n = 34,033) and the British Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (BCCSS; n = 34,489) have been central to understanding late mortality and morbidity(Reference Fidler, Reulen and Winter46,Reference Robison, Mertens and Boice47) . A joint analysis (n = 49,822) revealed lower early but higher long-term mortality among United States (US) survivors, largely from secondary malignancies and cardiopulmonary disease, highlighting international differences(Reference Fidler-Benaoudia, Oeffinger and Yasui48).

Other cohorts, including Adult Life After Childhood Cancer in Scandinavia (n = 33 160)(Reference Asdahl, Winther and Bonnesen49), the Dutch Childhood Oncology Group-Long-Term Effects After Childhood Cancer cohort (DCOG LATER; n = 6,165)(Reference Kok, Teepen and van der Pal50) and the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study (SJLIFE; n = 8,192)(Reference Howell, Bjornard and Ness51), show that 60–90% of survivors develop at least one chronic condition, often severe, by mid-adulthood(Reference Oeffinger, Mertens and Sklar52–Reference Bhakta, Liu and Ness54). By age 50, nearly all SJLIFE participants had ≥1 chronic condition, and 96% had at least one severe complication. Survivors experienced an avaerage of 4.7 servere conditions, compared with 2.3 in matched community controls. Endocrine and skeletal complications are common, affecting up to half of survivors, including hormonal imbalances, growth impairment and reduced bone density(Reference Rossi, Tortora and Paoletta55,Reference Isaksson, Bogefors and Åkesson56) .

Evidence for adolescent and young adult (AYA) survivors is more limited, due to differences in tumour biology, treatments and care pathways(Reference Woodward, Jessop and Glaser57,Reference Barr, Ferrari and Ries58) . Available datasets often lack detailed exposure, comorbidity and lifestyle data, limiting identification of modifiable risks. United Kingdom (UK) data from the Teenage and Young Adult Cancer Survivor Study (TYACSS) show elevated late morbidity, including four-fold higher cardiac mortality in survivors diagnosed at 15–19 years and 40% higher cerebrovascular hospitalisation risk across 15–39 years(Reference Henson, Reulen and Winter59,Reference Bright, Hawkins and Guha60) .

Adult survivors face increased risks of cardiovascular disease (CVD), metabolic syndrome, diabetes and osteoporosis from treatment-induced metabolic and endocrine disruption. On average, survivors develop 1.9 new medical conditions post-cancer, with higher comorbidity 10–14 v. 4–9 years after diagnosis(Reference Leach, Weaver and Aziz44). Arizona Behavioural Risk Factor Surveillance System data indicate 34% of survivors had ≥3 chronic conditions, compared with 11.4% of controls(Reference Singh, Gallaway and Rascon61). Comorbidity burden varies by cancer type; breast and endometrial survivors experience the highest post-diagnosis condition rates, with CVD particularly elevated in breast cancer(Reference Hamood, Hamood and Merhasin62). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data from the US show increased metabolic syndrome, highest in males with haematologic cancer and females with cervical cancer(Reference Ezeani, Tcheugui and Agurs-Collins63).

Osteoporosis is common, accelerated by iatrogenic menopause and hormone-blocking therapies, with elevated fracture risk in advanced cancers(Reference Cann, Martin and Genant64–Reference Rees-Punia, Newton and Parsons66). Sarcopenia and sarcopenic obesity, driven by systemic therapies, predict poorer outcomes and affect up to 81% of some cancer populations(Reference Ryan, Power and Daly67,Reference Jogiat, Bédard and Sasewich68) . Integrated nutrition and exercise support is critical, yet screening remains limited.

Gaps in the evidence base

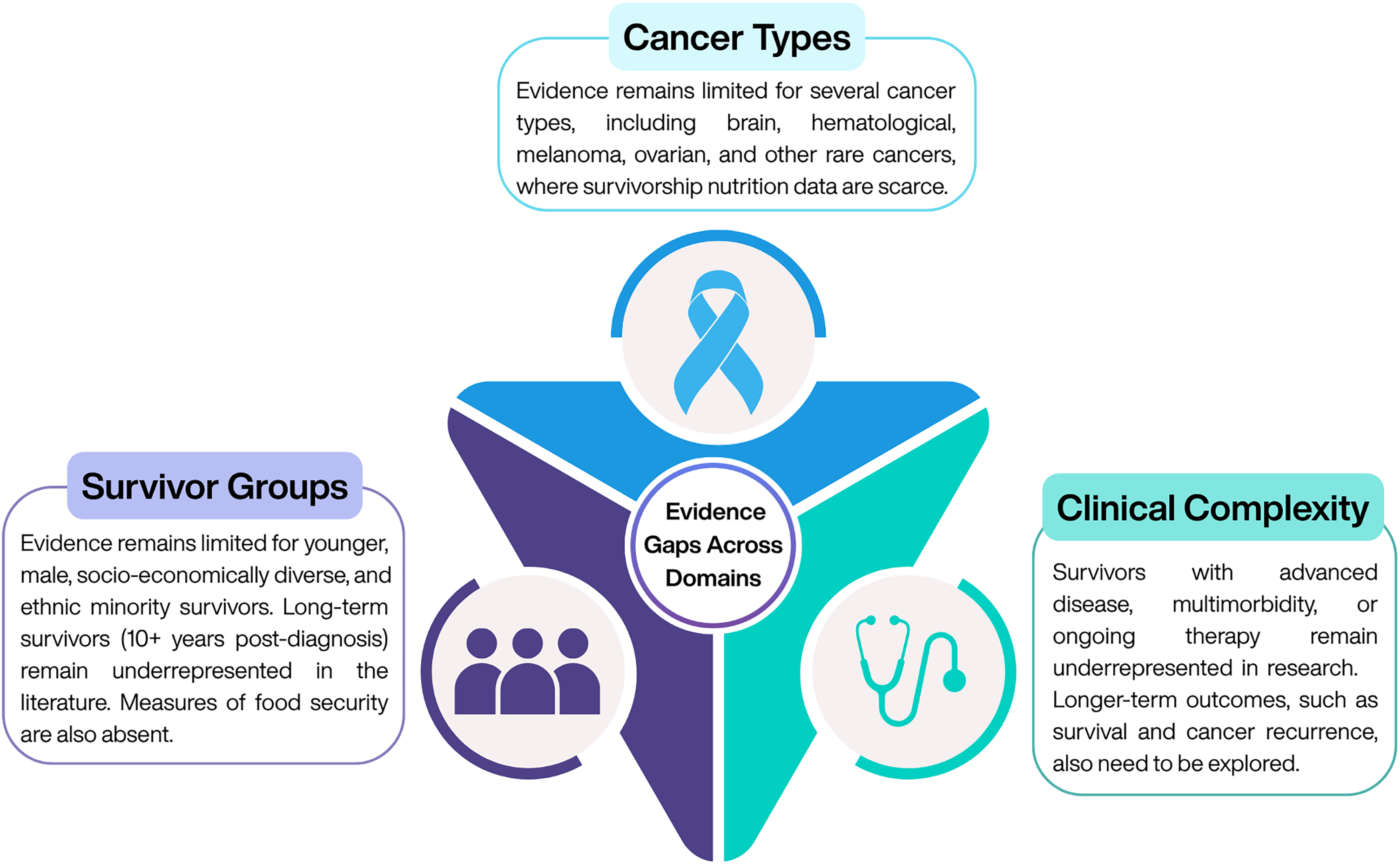

Despite growing evidence supporting the role of nutrition in cancer survivorship, significant gaps within the current literature limit the generalisability and application of findings across diverse survivor populations (Figure 2). Research to date has predominantly focused on survivors of common cancers(Reference Feuerstein, Gehrke and Wronski69), with limited data available for those with brain, haematological, ovarian, melanoma and rare cancers(Reference de Heus, van der Zwan and Husson70), where disease trajectories, treatment toxicities and nutritional needs may differ substantially. Important demographic groups also remain underrepresented, including younger survivors, men, individuals from socio-economically disadvantaged or lower-education backgrounds and ethnic minority populations, all of whom may face distinct barriers to accessing and engaging with nutritional care. In addition, evidence is sparse for survivors with more complex clinical needs, such as those with advanced or progressive disease, multi-morbidity or those receiving ongoing anti-cancer therapy. Finally, most existing nutrition intervention studies focus on short-term behavioural or physiological outcomes, with a notable lack of long-term data on survival, cancer recurrence and sustained QoL benefits(Reference Egger-Heidrich, Wolters and Frick71). Addressing these gaps is essential to develop equitable, evidence-informed nutritional guidance that meets the needs of all cancer survivors.

Figure 2. Current gaps in the evidence.

Guidelines and recommendations

Despite growing recognition of nutrition’s role in survivorship, guidance remains broad, non-specific and rarely tumour- or treatment-tailored. In 2018, the World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF) International published ‘Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Cancer: a Global Perspective’, acknowledging that it is increasingly unlikely that specific foods, nutrients or other components of foods themselves cause or prevent cancer(72). Instead, the report emphasised that various patterns of diet and physical activity interact to create a metabolic state that can either favour or hinder the genetic and epigenetic changes responsible for the cellular structural and functional alterations underlying the principal mechanisms of cancer progression. In summary, the WCRF highlights that whilst following each individual recommendation (be a healthy weight, be physically active, eat wholegrains, vegetables, fruit and beans, limit ‘fast foods’, limit red and processed meat, limit sugar-sweetened drinks, limit alcohol consumption, do not use supplements for cancer prevention, for mothers: breastfeed your baby, if you can, after a cancer diagnosis, follow our recommendations, if you can) will be of benefit in relation to cancer protection, most benefit is gained from treating all 10 recommendations as an over-arching package. Currently, cancer survivors are recommended to follow the WCRF/American Institute for Cancer Research recommendations for cancer prevention(72). Multiple cohort studies indicate that cancer survivors adhering closely to these recommendations, including healthy weight, regular physical activity, plant-based diets and limited red/processed meat, sugar-sweetened beverages and alcohol, experience significantly better outcomes. In the Moli-sani Study (n = 786 survivors, 12-year follow-up), high adherence (score >5/7) was associated with 46% lower all-cause mortality (HR 0.54, 95% CI 0.37–0.78, P value = 0.0010), with each additional adherence point linked to a 22% reduction(Reference Calder, Martinez and Di Castelnuovo73). In colorectal cancer survivors (n = 1 491 patients, median 8 years), the highest quartile of adherence (diet, physical activity, BMI) was associated with 37% lower mortality, with even stronger associations when BMI was excluded(Reference Song, Petimar and Wang74). Higher adherence is also linked to improved QoL and lower symptom burden in adolescent/young adult survivors in the Netherlands, including reduced fatigue and better global QoL(Reference Kenkhuis, Vlooswijk and Janssen75). Most evidence derives from observational cohorts, with limited data stratified by cancer subtype or treatment.

Other existing guidelines largely reiterate existing WCRF recommendations(72). The European Society of Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN)(Reference Arends, Bachmann and Baracos76) includes two recommendations for cancer survivors: engaging in regular physical activity and maintaining a healthy body weight (BMI 18.5–25 kg/m2) through a balanced diet rich in vegetables, fruits and whole grains and low in saturated fat, red meat and alcohol. The American Cancer Society(Reference Rock, Thomson and Sullivan77) similarly focuses on physical activity and nutrition, highlighting the impact of tumour- and treatment-related symptoms on nutritional status. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network Survivorship Guidelines advocate a multidisciplinary approach, supporting optimal body composition with lower fat mass and higher muscle mass and a predominantly plant-based, nutrient-dense diet that includes healthy fats, whole grains and lean protein sources(Reference Sanft, Day and Ansbaugh78–80). Red and processed meats, refined sugars and highly processed foods should be limited. The European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) and the American Society of Clinical Oncology address lifestyle considerations, promoting healthy weight, physical activity, limited alcohol and bone health monitoring(Reference Loibl, André and Bachelot81,Reference Burstein, Lacchetti and Anderson82) . Similarly, the Clinical Oncology Society of Australia encourages wellness programmes and allied health referrals(Reference Vardy, Chan and Koczwara83). Specific, standalone clinical nutrition guidelines tailored to AYA cancer survivors remain limited. Although survivorship frameworks such as the Children’s Oncology Group Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines include nutrition and lifestyle recommendations, these are embedded within broader, healthcare-professional directed survivorship care rather than presented as dedicated AYA-specific nutrition guidelines(Reference Kenkhuis, Vlooswijk and Janssen84,85) .

Throughout these recommendations, implementation strategies remain limited. Broader population frameworks, such as Ireland’s Food Pyramid(86) and the UK Eatwell Guide(87), provide visual tools but lack survivorship specificity. Future guidelines should provide tailored recommendations that reflect the unique nutritional challenges associated with specific cancers and treatments.

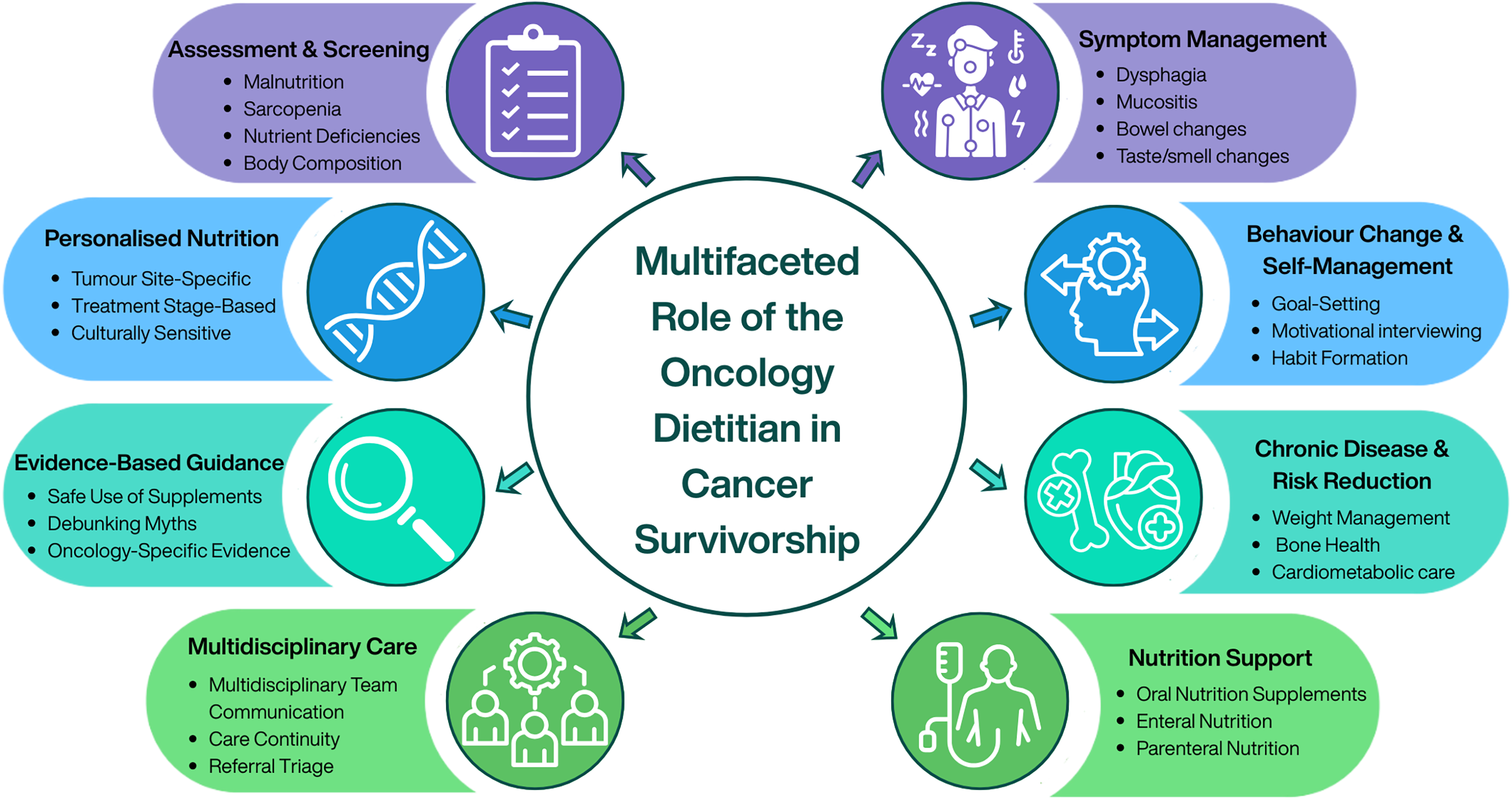

The multifaceted role of the oncology dietitian in cancer survivorship

Dietitians play a critical role in assessing, preventing and managing nutrition-related complications across the cancer care continuum (Figure 3). Within survivorship, their role extends beyond addressing treatment-related nutrition impact symptoms to enabling long-term health optimisation, supporting behaviour change and reducing risk of comorbidities such as CVD, metabolic dysfunction, osteoporosis, sarcopenia and malnutrition. Using evidence-based, personalised counselling, dietitians provide tailored interventions that account for tumour site, treatment exposure, comorbidities and individual preferences. They also contribute to multidisciplinary care by identifying patients at nutritional risk, implementing timely interventions, supporting self-management and guiding safe, appropriate use of supplements, evaluating emerging diets and highlighting misinformation. Integrating oncology dietitians into survivorship pathways is therefore essential to deliver equitable, effective and sustainable nutrition care.

Figure 3. Multifaceted role of the oncology dietitian in cancer survivorship care.

The realities of practice

Unmet need for support

A growing body of research highlights that cancer survivors are actively seeking nutrition guidance to manage the side effects of treatment, reduce recurrence risk and support long-term health. Sullivan et al. (Reference Sullivan, Rice and Kingston12) found that 60.9% of breast cancer survivors and nearly 30% of lung cancer survivors reported a clear desire for access to dietary support during follow-up care. This strong demand is echoed in both quantitative and qualitative studies. For example, Cushen et al. (Reference Cushen, Murphy and Johnston11) found that many women reported feeling lost and unsupported after treatment, describing a noticeable drop-in care once structured medical intervention ended. Participants voiced a strong desire for ongoing, tailored dietary advice as part of survivorship care. Similarly, Hussey et al. (Reference Hussey, Hanbridge and Dowling88) highlighted survivors’ need for long-term support in adopting and maintaining healthy eating and physical activity habits. Together, these findings illustrate a persistent and widespread need for accessible, evidence-based nutrition counselling throughout the survivorship journey, one that remains largely unmet in current care models.

Despite this demand, the vast majority of survivors do not receive adequate nutritional support. Only 12% of cancer survivors report receiving advice from a registered dietitian(Reference O’Callaghan, Douglas and Keaver10). In the absence of professional guidance, many turn to informal sources such as family, friends or the internet(Reference Keaver, Richmond and Rafferty15), which significantly increases the risk of confusion and misinformation(Reference Mullee, O’Donoghue and Dhuibhir14). Even cancer-specific health websites often lack accurate, evidence-based nutrition content tailored to the needs of survivors(Reference Keaver, Loftus and Quinn89–Reference Keaver, Callaghan and Walsh91).

Leading professional bodies, including the ESMO(Reference Arends, Strasser and Gonella92), recommend that nutrition care be embedded within multidisciplinary survivorship services. However, this is rarely implemented in practice, leaving a significant gap between survivor needs and service provision.

Barriers to providing nutrition support

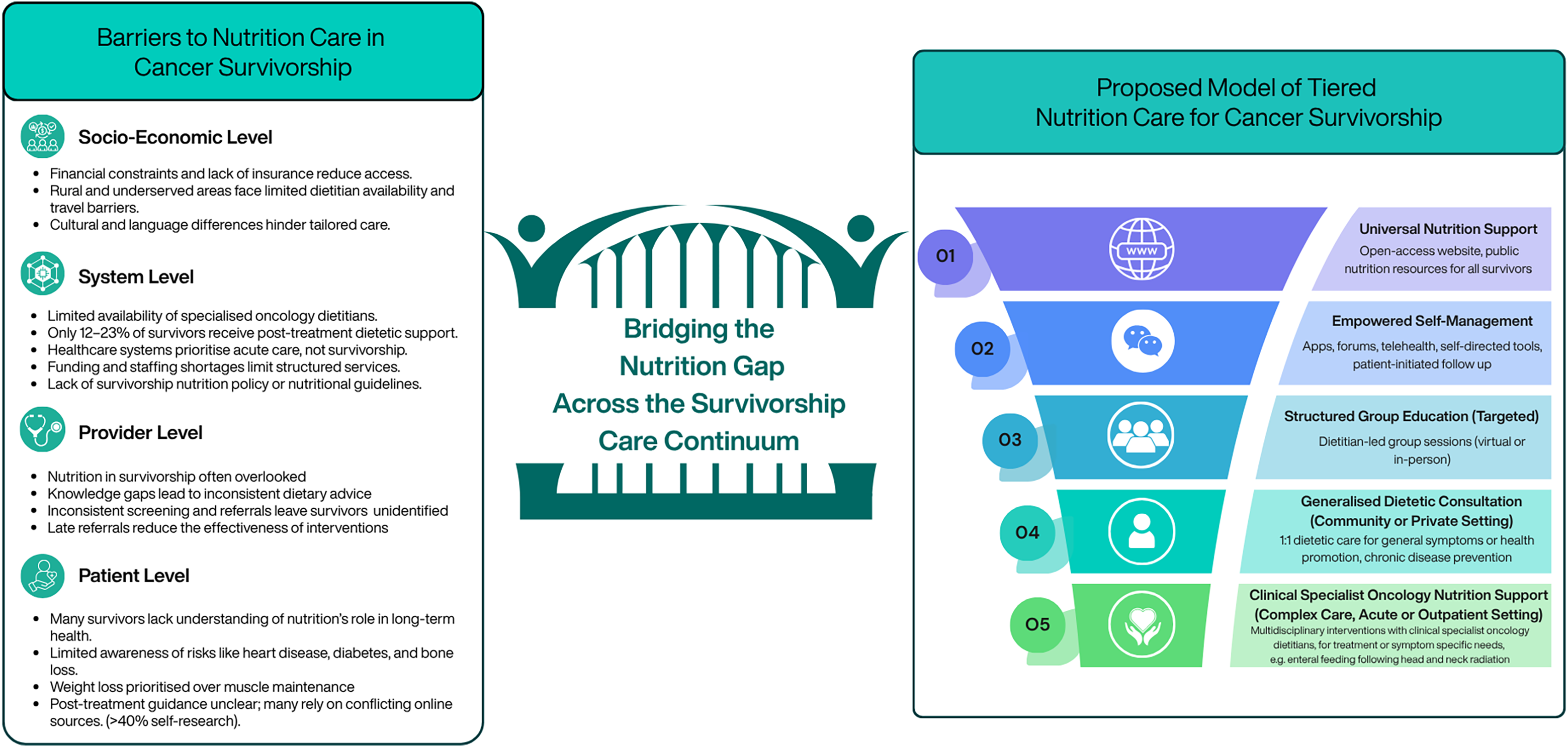

The value of nutritional support in cancer survivorship is well-established(Reference Rock, Thomson and Sullivan77,Reference Bourke, Homer and Thaha93) , yet substantial barriers limit access to dietetic care for many survivors (Figure 3). These barriers operate at the patient, healthcare provider and system levels. From the patient perspective, many survivors do not fully understand the role of nutrition in preventing or managing long-term health risks such as CVD, diabetes or bone loss. For instance, Deery et al. (Reference Deery, Johnston and Butler94) and Sullivan et al. (Reference Sullivan, Rice and Kingston12) observed that over half of surveyed survivors adopted lifestyle behaviours for weight loss, often without considering muscle mass preservation, which may be more beneficial for long-term outcomes(Reference Rinninella, Fagotti and Cintoni95–Reference Daly, Prado and Ryan98). Many survivors also lack reliable dietary guidance and may rely on unverified sources, with 40.6% of Irish survivors reporting self-directed online research(Reference Sullivan, Rice and Kingston12,Reference Ryding, Rigby and Johnston99) .

Healthcare provider factors further impede access. Members of multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) may underestimate the importance of nutrition, and dietitians themselves often report uncertainty regarding evidence-based interventions in survivorship(Reference Keaver, Richmond and Rafferty15,Reference Curtis, Kiss and Livingstone16) . Inconsistent nutritional screening and referral practices mean at-risk survivors may not be identified promptly, reducing the effectiveness of dietary interventions(Reference Sullivan, Rice and Kingston12,Reference Kristensen, Wessel and Ustrup100) .

System-level limitations include insufficient availability of specialised oncology dietitians and prioritisation of acute treatment over long-term care. Only a minority of patients receive post-treatment dietetic support: 23% in Australia(Reference Baguley, Benna-Doyle and Drake13), 12% in Ireland(Reference O’Callaghan, Douglas and Keaver10) and 12% of women with ovarian cancer(Reference Johnston, Veenhuizen and Ibiebele101). Even during treatment, access is suboptimal, with around one in three patients reporting dietitian advice(Reference Sullivan, Rice and Kingston12,Reference Mullee, O’Donoghue and Dhuibhir14,Reference Keaver, Richmond and Rafferty15) . Financial constraints, geographic disparities and cultural or language barriers further limit access, particularly for rural or underserved populations(Reference Scott and Hoskin17,Reference McDougall, Anderson and Adler Jaffe102–Reference Cuevas, O’Brien and Saha105) . In addition, the integration of nutrition into cancer care is significantly limited by the absence of survivor-specific dietary recommendations and the lack of policy mandates and structured funding models, resulting in inconsistent implementation and inequitable access to specialised nutritional support.

Addressing these barriers requires adequate dietetic staffing, professional education, evidence-based resources and systematic referral pathways. Strengthening patient knowledge, MDT integration and access to care is essential to enable timely, targeted nutritional interventions that support long-term survivorship and mitigate ongoing treatment-related effects(Reference Ryding, Rigby and Johnston99).

Bridging the gap: nutrition interventions for cancer survivorship

Despite limited access to dietetic care after active treatment, growing evidence shows that nutrition interventions can improve outcomes for cancer survivors. While the importance of dietetic care during cancer treatment is well-established(Reference Soares, Beuren and Friedrich106), there remains a critical gap in understanding how best to support survivors in the post-treatment phase. Evidence supporting the role of nutritional interventions in cancer survivorship is steadily growing. A recent systematic review by Ryding et al. (Reference Ryding, Rigby and Johnston99) found that dietitian-led interventions in primary care can improve body composition and QoL and promote intentional weight loss, particularly among breast cancer survivors. These programmes addressed diverse nutritional needs, from undernutrition to obesity, and used varied delivery methods, including individual counselling, group education, telephone consultations, cooking classes and social media engagement(Reference Ryding, Mitchell and Rigby107).

Evidence for dietetic interventions among AYA cancer survivors remains limited and methodologically heterogeneous. The Cochrane review by Cohen et al. (Reference Cohen, Wakefield and Cohn108) identified only three small randomised controlled trials evaluating calcium and vitamin D supplementation, nutrition counselling and lifestyle education. Mays et al. (Reference Mays, Gerfen and Mosher109,Reference Mays, Black and Mosher110) had 75 adolescent survivors aged 11–21 years; Cox et al. (Reference Cox, McLaughlin and Rai111) included 266 adolescents post-treatment aged 12–18 years; and Rai et al. (Reference Rai, Hudson and McCammon112) recruited 275 survivors aged up to 18 years. Behavioural education increased self-reported cow’s milk intake and calcium supplement use(Reference Mays, Gerfen and Mosher109,Reference Mays, Black and Mosher110) , while multicomponent counselling reduced junk-food intake without broader dietary change(Reference Cox, McLaughlin and Rai111). Calcium and vitamin D supplementation had no effect on bone mineral density at 36-month follow-up(Reference Rai, Hudson and McCammon112). Subsequent systematic reviews reaffirmed the limited and heterogeneous evidence base, with most studies focusing on feasibility rather than long-term efficacy(Reference Vasconcelos and Sousa113). In contrast, the evidence for physical-activity interventions in survivorship is far more extensive(Reference Coffman, Choi and Smitherman114), while nutrition-specific programmes remain scarce. Recent trials involving AYA cancer survivors that utilise digital and multicomponent strategies have demonstrated promising feasibility and behavioural outcomes; however, adolescents are underrepresented in current nutrition interventions(Reference Skiba, McElfresh and Howe115). Lynch et al. (Reference Lynch, Stricker and Brown116) conducted a 12-month web-based lifestyle programme with 46 participants (mean age 39 ± 6.2 years), resulting in a 5.3% weight loss and improved adherence to healthy behaviours. De Nysschen et al. (Reference DeNysschen, Panek-Shirley and Zimmerman117) implemented an eight-week supervised exercise and nutrition education programme for 24 AYA survivors (mean age 16.6 years), resulting in reduced fatigue and improvements in QoL and nutrition knowledge, with social support being the participants’ favourite component.

Exploring varied delivery models for nutrition interventions has become essential, as survivorship encompasses a vast and heterogeneous population and dietetic staffing within primary care remains limited (as previously discussed). Expanding beyond traditional one-to-one counselling towards digital, group-based and hybrid delivery formats for the majority of survivors may therefore help to bridge gaps in service provision while maintaining personalised support.

Hybrid delivery models and integration of patient-reported outcomes have emerged as key strategies for tailoring care to survivors’ needs and preferences(Reference Cushen, Murphy and Johnston11,Reference Johnston, O’Connell and McSharry118) . While individual counselling remains central, combined or tiered models that incorporate group education alongside one-to-one support may enhance efficiency and motivation(Reference Keaver, Richmond and Rafferty15,Reference Johnston, O’Connell and McSharry118,Reference Burden, Wolfenden and Sremanakova119) . The Improved nutrition in adolescents and young adults after childhood cancer (INAYA trial; n = 23, median age 20 years) found that intensive, dietitian-led counselling delivered through a hybrid of in-person and telehealth sessions significantly improved diet quality post-treatment(Reference Quidde, von Grundherr and Koch120). Individualised or multicomponent interventions generally yield greater benefits than standardised or group-only formats(Reference Reeves, Terranova and Winkler121). Digital and remote approaches, including mobile apps, text messaging and telehealth interviewing, have shown promise in improving weight, diet quality, physical activity and selected QoL measures(Reference Brown, Sarwer and Troxel122,Reference Raji Lahiji, Sajadian and Haghighat123) . The sustainability of outcomes varies by delivery mode, programme duration and participants’ ability to maintain healthy behaviours independently(Reference Lisevick, Cartmel and Harrigan124,Reference Sanft, Usiskin and Harrigan125) . Improvements in psychosocial outcomes, such as QoL, fatigue, depression and self-efficacy, are inconsistent and often limited to participants achieving ≥5% weight loss(Reference Johnston, O’Connell and McSharry118). Different dietary approaches (e.g. Mediterranean, low-glycaemic, plant-based or commercial programmes) and inconsistent reporting of adherence make it hard to know which strategies are most effective or sustainable. It is also unclear how much of the benefit comes from diet alone v. combined lifestyle interventions(Reference Li, Zhang and Li126,Reference Wright, Walker and Broadbent127) . Integrated diet and lifestyle interventions may contribute to improved survival and QoL, but confounding factors and limited follow-up constrain causal interpretation(Reference Wright, Walker and Broadbent127). Biomarker outcomes, including telomere length, leptin and cytokine profiles, show inconsistent results, largely due to small sample sizes(Reference Ryding, Rigby and Johnston99,Reference Castro-Espin and Agudo128) . Only a handful of studies have evaluated effects on recurrence or survival(Reference Ilerhunmwuwa, Khader and Smith129,Reference Yeganeh, Willey and Wan130) , underscoring the need for more rigorous, long-term and diverse research.

In Ireland, survivorship care models are evolving towards nurse-led and dietitian-led clinics, exemplified by the Linking You to Support and Advice (LYSA) randomised control trial, which provides one-to-one dietetic support to breast and gynaecological cancer survivors(Reference Johnston, O’Connell and McSharry118), and the LIAM Mc Trial, which delivers structured group-based education to men impacted by metastatic genitourinary cancer(Reference Noonan, Bredin and Cahill131). Both integrate symptom management, dietetic input and electronic patient-reported outcomes. These developments reflect a shift towards proactive, multidisciplinary management of the long-term and late effects of cancer treatment. However, a national, structured approach to dietetic care for cancer survivors remains absent.

Existing chronic disease frameworks offer valuable guidance for developing cancer survivorship programmes. For example, the ExWell(Reference Kehoe, Skelly and Moyna132) exercise rehabilitation programme and Diabetes Self-Management Education and Support models, such as Diabetes Education and Self-Management for Ongoing and Newly Diagnosed people (DESMOND)(Reference Scannell, O’Neill and Griffin133) and Community Orientated Diabetes Education (CODE)(134), demonstrate how structured group delivery, peer support, facilitator training and behaviour-change strategies can promote self-management, sustainable behaviour change and improved health outcomes. These principles could be adapted to inform scalable, evidence-based group nutrition education for cancer survivors.

Moving forward: a new proposed model of care

Building on these frameworks, we propose a tiered model of nutrition care in cancer survivorship (Figure 4). The model begins with universal nutrition support and progresses to more personalised, dietitian-led guidance based on individual risk, need and readiness to engage. This approach aims to address key barriers in survivorship nutrition, such as limited specialist dietetic capacity, inconsistent referral pathways and inequitable access to post-treatment care, while promoting consistent, evidence-based practice across the continuum.

Figure 4. Current barriers to nutrition in survivorship care and a new proposed model for integrating nutrition care into current practice to meet the needs of all cancer survivors.

Informed by existing research and responsive to gaps in current practice, the model integrates flexible delivery formats, including virtual and community-based sessions, combining dietary education, practical skill-building, peer support and behaviour-change techniques. Programmes are tiered to match individual nutritional and functional needs, supporting survivors both during and after treatment and providing a foundation for sustainable, patient-centred nutrition care in cancer survivorship.

Conclusion

Nutrition plays a critical role in optimising long-term health outcomes for cancer survivors, yet meaningful integration of nutritional care into survivorship pathways remains inconsistent. Despite clear recognition from both patients and healthcare professionals of the value of nutrition in managing late effects, improving QoL and reducing risk of recurrence and comorbidities, the provision of guidance is limited and often fragmented. This gap is driven by multiple barriers, including limited nutrition knowledge and confidence among healthcare professionals, competing clinical priorities, time constraints and the absence of standardised pathways or national recommendations. The tiered model proposed by the authors offers a pragmatic and scalable solution to address these inequities. By providing accessible, evidence-based information for all cancer survivors, alongside mechanisms to identify those requiring more individualised or specialist dietetic support, this model has the potential to embed nutrition as a core component of survivorship care. Implementing such a framework could help ensure that every cancer survivor receives timely, appropriate and effective nutrition support, ultimately improving survivorship outcomes at a population level.

Acknowledgements

We would like to dedicate this review to the memory of Dr Julie Wallace and her valuable contributions to nutrition science.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Author contribution

L.K. delivered the Julie Wallace Lecture. L.K., SJ.C., N.O’C and KE.J co-wrote the paper and developed the images and tables. L.K. had primary responsibility for the final content.