Introduction

Men’s Sheds are a unique community-based mutual-aid membership association, with nearly 3500 Sheds currently across Australia, Canada, Denmark, Ireland, Japan, Kenya, New Zealand, South Africa, UK and the USA, with a focus on men’s well-being (Australian Men’s Shed Association, 2024). The Men’s Sheds movement aims to replicate the traditional Australian backyard Shed where men would ‘hang out’ together and engage in outdoor activities, alone or together, such as carpentry, small construction work and gardening (Australian Men’s Shed Association, 2024; Wilson & Cordier, Reference Wilson and Cordier2013). Whilst originally developed to target the increasing incidence of poor mental and physical well-being, social isolation and loneliness experienced by retired men (Earle et al., Reference Earle, Earle and Von Mering1996), the Sheds now encourage younger men to join, and some Sheds also include women members.

The voluntary sector includes large numbers of membership associations, with nearly 20,000 non-profit associations and clubs in Western Australia alone (WA Department of Energy & Mines, 2022). Many of these organisations are mutual-aid groups, where people with similar problems, interests or goals come together for support and socialisation (Adamsen & Rasmussen, Reference Adamsen and Rasmussen2001). Mutual-aid groups are organised by members, for the members, and focus on reciprocity between members (Munn-Giddings & Borkman, Reference Munn-Giddings, Borkman, Ramon and Williams2005). These associations have been identified as an essential component of a thriving community (Putnam, Reference Putnam2000), and are associated with higher mental health and well-being for their members (McEvoy et al., Reference McEvoy, Holmes, Smith, Bullen, Chiu, Wild, Ashley and Talbot2023). Despite the prevalence of these groups within the non-profit sector, there has been limited research about such associations (Tschirhart & Gazley, Reference Tschirhart and Gazley2014).

Mutual-aid groups differ to that of professionally-led support groups because they are focussed on both giving and receiving support (Munn-Giddings & Borkman, Reference Munn-Giddings, Borkman, Ramon and Williams2005), and are not organised or led by professionals. As well as member benefits, membership organisations offer added social value to their wider communities including increased social capital (Mutz et al., Reference Mutz, Burrmann and Braun2022) and supporting entrepreneurship (Teckchandani, Reference Teckchandani2014). These groups can include peer support groups for mental health (Lammers et al., Reference Lammers, Dobslaw, Stricker and Wegner2023), community sports clubs (Doherty & Cuskelly, Reference Doherty and Cuskelly2020), and heritage supporter groups (Holmes & Slater, Reference Holmes and Slater2012) as well as Men’s Sheds. While studies have revealed the benefits of these groups to their members and the wider community such as increased social connections leading to greater social capital (Putnam, Reference Putnam2000), little is known about what factors contribute to a creating a thriving mutual-aid membership association and this paper investigates this at the Shed level. While there is a small state-wide umbrella association with paid staff, each Shed operates as an entirely volunteer-run membership group.

There is a growing literature on the Men’s Sheds movement, including several review papers (Foettinger et al., Reference Foettinger, Albrecht, Altgeld, Gansefort, Recke, Stalling and Bammann2022; Kelly et al., Reference Kelly, Steiner, Mason and Teasdale2019; McEvoy et al., Reference McEvoy, Holmes, Smith, Bullen, Chiu, Wild, Ashley and Talbot2023). These review papers, including a logic model developed by Kelly et al (Reference Kelly, Steiner, Mason and Teasdale2019) have identified a range of factors from the extant literature that can impact negatively on a Men’s Shed such as autocratic leadership or funding shortages. An empirical exploration of how these factors impact on a Men’s Shed has the potential to identify the necessary characteristics for a thriving membership association more broadly. This paper, therefore, seeks to extend this literature and answer the research question of what makes a thriving Men’s Shed, drawing on the concept of a thriving organisation (Parker et al., Reference Parker, Jorritsma, Griffin, Brough, Gardiner and Daniels2022) and we operationalised thriving Men’s Sheds as those that provide the conditions that optimise member mental health and well-being.

Given the limited research on membership associations, we applied the concept of recruitability (Haski-Leventhal et al., Reference Haski-Leventhal, Meijs and Hustinx2010), which ‘refers to the ability of volunteer organizations to recruit volunteers and maintain them’ (p. 142). To contextualise this theory—developed for volunteer organisations with a volunteer manager—we use Kelly et al.’s logic model (Reference Kelly, Steiner, Mason and Teasdale2019), which proposes the key elements required in a Men’s Shed to generate positive health outcomes. These theories, along with the literature review, provide a framework for an empirical investigation of the factors that lead to a thriving Shed with the potential to offer a framework to memberships associations more widely. In doing so, this paper takes a macro-level approach to examine Men’s Sheds the beyond the current focus of individual members health benefits.

Literature Review

Most research on Men’s Sheds has primarily focused on the health benefits of individual members (McEvoy et al., Reference McEvoy, Holmes, Smith, Bullen, Chiu, Wild, Ashley and Talbot2023) rather than the organisation. This is encapsulated in Kelly et al.’s logic model of health and well-being outcomes from Men’s Sheds activities (2019). Drawing on a literature review, Kelly et al. (Reference Kelly, Steiner, Mason and Teasdale2019) identified inputs, mediating variables and outcomes associated with better physical and mental health, and well-being. These inputs included health and non-health focused items. Non-health items were a space for practical and physical activities; educational opportunities to learn or share skills; a place to socialise and interact; a space that is not home; and equal and inclusive space; and a place of refuge and safety. Further studies have identified the key factors impacting a Shed’s success including leadership and governance, funding, and physical location, size and structure (Foettinger et al., Reference Foettinger, Albrecht, Altgeld, Gansefort, Recke, Stalling and Bammann2022). In the next sections, we review the factors relating to Men’s Sheds and membership associations more broadly.

Leadership and Governance

The style and quality of leadership from the Shed leaders were commonly mentioned as impacting on the experience of Shedders, in particular, the relationship between the Shed leaders and the members (Ang et al., Reference Ang, Cavanagh, Southcombe, Bartram, Marjoribanks and McNeil2017; McGeechan et al., Reference McGeechan, Richardson, Wilson, O’Neill and Newbury-Birch2017; Robinson, Reference Robinson2019; Southcombe et al., Reference Southcombe, Cavanagh and Bartram2015). Strong quality leader–member relationships within the Shed were associated with greater social connectedness, and health and well-being amongst the members (Ang et al., Reference Ang, Cavanagh, Southcombe, Bartram, Marjoribanks and McNeil2017; McGeechan et al., Reference McGeechan, Richardson, Wilson, O’Neill and Newbury-Birch2017; Southcombe et al., Reference Southcombe, Cavanagh and Bartram2015). The ability of the Shed leaders and coordinators to facilitate quality relationships, as well as support their members, likely contributed to feelings of belongingness and greater well-being amongst the members of these Sheds (McGeechan et al., Reference McGeechan, Richardson, Wilson, O’Neill and Newbury-Birch2017; Southcombe et al., Reference Southcombe, Cavanagh and Bartram2015). Some men in McGeechan et al.’s (Reference McGeechan, Richardson, Wilson, O’Neill and Newbury-Birch2017) study even commented on how they felt the support from the Shed coordinator was responsible for “turning their lives around” (p. 253).

Furthermore, lack of support from coordinators and authoritarian leadership within the Shed was often associated with negatively influencing the social connectedness and well-being of members. In some Sheds, the coordinators attempted to control too many aspects and the members felt trapped (Robinson, Reference Robinson2019; Southcombe et al., Reference Southcombe, Cavanagh and Bartram2015). In contrast, having ‘just enough’ rules and structure within the Shed was identified as being important to allow the men to engage in activities that were meaningful for them (Robinson, Reference Robinson2019). Sheds with rigid rules or hierarchical were perceived as restrictive. Coordinators who listened to their members, were proactive and placed the Sheds’ needs first were praised. McGrath et al. (Reference McGrath, Murphy and Richardson2022) identified the critical importance of creating a safe environment for members. Members valued participant-driven organisation of the Shed, which gave them autonomy over their activities (Foettinger et al., Reference Foettinger, Albrecht, Altgeld, Gansefort, Recke, Stalling and Bammann2022).

Funding and Resources

Funding and how this impacted on members of the Sheds was mentioned in several studies (Hansji et al., Reference Hansji, Wilson and Cordier2015; Kelly et al., Reference Kelly, Teasdale, Steiner and Mason2021; Lefkowich & Richardson, Reference Lefkowich and Richardson2016; Robinson, Reference Robinson2019). These studies include Australia, Scotland, Ireland, and New Zealand, respectively, so this appears to be a broad issue. These studies all highlighted the pressure that a lack of funds can place on the Sheds and its members. Insufficient funding could also limit the activities a Shed offered its members (Foettinger et al., Reference Foettinger, Albrecht, Altgeld, Gansefort, Recke, Stalling and Bammann2022). If a Shed was externally funded by a local government agency or other organisation, there was less pressure on the Shed members. However, the Shed committee may still be under pressure to apply for grants or sponsorship.

Many members produced items in their Sheds, such as furniture, kitchenware, art, and toys, to sell at local markets, whereas other Sheds sometimes offered a paid service to fix community features such as park benches (Cavanagh et al., Reference Cavanagh, McNeil and Bartram2013). Whilst these activities were beneficial as they generated income for the Shed to ensure its continuity, they placed unwanted obligations on members. These obligations could create a paradox whereby Shed members were put under stress to work for free, and therefore were not receiving the full health and well-being benefits associated with attendance at Men’s Sheds (Kelly et al., Reference Kelly, Teasdale, Steiner and Mason2021). Comparatively, Sheds that were not self-funded, and therefore did not rely on the members producing tangible goods, reported how the members did not feel pressured and could enjoy the social, health and well-being benefits of the Shed (Hansji et al., Reference Hansji, Wilson and Cordier2015).

Whilst a lack of funding presented additional stress and obligations to the members, it appeared that some members viewed this positively, as a way to feel satisfied with their membership. As was highlighted by Robinson (Reference Robinson2019), working on producing items to sell, and other projects to create income for the Shed, allowed some members to demonstrate and use their skills and capabilities for the benefit of the Shed, and thus potentially positively affecting their individual well-being. Similarly, a participant expressed that working together with other Shed members and providing an income for the Shed led to some of the members having a “big smile on our face at the end of the day” (Robinson, Reference Robinson2019, p. 49).

Men’s Sheds also rely on their members as volunteers to organise the Shed and its activities. This is rarely discussed in studies specific to Men’s Sheds, however it is widely addressed in the broader membership associations’ literature. Doherty and Cuskelly (Reference Doherty and Cuskelly2020), for example, acknowledge the importance of volunteer succession for community sport clubs and Gazley and Brudney (Reference Gazley and Brudney2014) uncover the informal volunteering by members that underpins these groups. The engagement of membership associations with external organisations also increases their resources (Doherty & Cuskelly, Reference Doherty and Cuskelly2020).

Physical Location, Size, and Structure of Sheds

Researchers also identified that the physical location, size and structure of Men’s Sheds could influence the health and well-being of its members (Ang et al., Reference Ang, Cavanagh, Southcombe, Bartram, Marjoribanks and McNeil2017; Haesler, Reference Haesler2015; Hansji et al., Reference Hansji, Wilson and Cordier2015; Kelly et al., Reference Kelly, Teasdale, Steiner and Mason2021; Lefkowich & Richardson, Reference Lefkowich and Richardson2016). The primary activity of Sheds is craftwork so it is important to have a common area where members can use their practical skills. Researchers have noted the challenge of this area being too small or inadequately resourced (Foettinger et al., Reference Foettinger, Albrecht, Altgeld, Gansefort, Recke, Stalling and Bammann2022; Ormsby, Reference Ormsby, Stanley and Jaworski2010). However, even those members who do not use the workshop for building produce reported enjoying being in the area to have conversations with the other men (Haesler, Reference Haesler2015). This space often allowed for the sharing of skills, learning and t for meaningful relationships to develop when engaging in activities that are mutually important.

While social interactions took place within the workshop space, two studies (Haesler, Reference Haesler2015; Hansji et al., Reference Hansji, Wilson and Cordier2015) highlighted the importance of having a separate social area within the Shed or nearby to the Shed. This could be the veranda of a Shed acting as a ‘common area’ for members to congregate and have meaningful conversations with other members (Haesler, Reference Haesler2015). Social interactions are a key feature of membership associations generally and can lead to societal benefits such as social capital formation (Mutz et al., Reference Mutz, Burrmann and Braun2022). Indeed, Waling and Fildes (Reference Waling and Fildes2017) noted the importance of Sheds as community gathering places. Interestingly, one study divided Sheds into two groups (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Cordier, Doma, Misan and Vas2015): the first were larger Sheds, focused on activities; the second were smaller Sheds, focused on social interaction. This suggests that it is difficult for a Shed to achieve both functions. Doherty and Cuskelly’s (Reference Doherty and Cuskelly2020) research on sports clubs also found that larger clubs were able to offer more activities as well as better quality programmes.

With regard to the location of Sheds, previous studies have included a mixture of urban and rural Sheds. Lefkowich and Richardson (Reference Lefkowich and Richardson2016) found that the location of the Shed may have negatively impacted the perception of the Shed and therefore influenced the number of health and well-being benefits for members. One Shed in their study was located in an industrial area on the outside of the city, and it was often called the “little black spot” (Lefkowich & Richardson, Reference Lefkowich and Richardson2016, p. 530). Thus, members of this Shed often reported experiencing marginalisation and harassment in the areas and alleyways adjacent to the Shed. In contrast, Sheds that found suitable locations that were perceived as safe and easy to access for the activities required to meet the members needs were likely to have more positive effects on the members’ health and well-being (Kelly et al., Reference Kelly, Teasdale, Steiner and Mason2021). In addition, some Men’s Sheds are shared spaces, which limits their opening times (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Burt, Pavkovic and Hayes2022).

We can conclude from this literature review that a Men’s Shed needs the following for the members to thrive: inclusive and supportive leadership, sufficient funding and resources, a sufficiently large workspace, an inclusive social space, and a safe and easily accessible location. While we have synthesised these factors from prior studies, concurrent with previous review papers there has been no empirical exploration of how these factors combine together in practice to create a thriving Shed. Next, we will present the theoretical framework underpinning this study.

Theoretical Framework

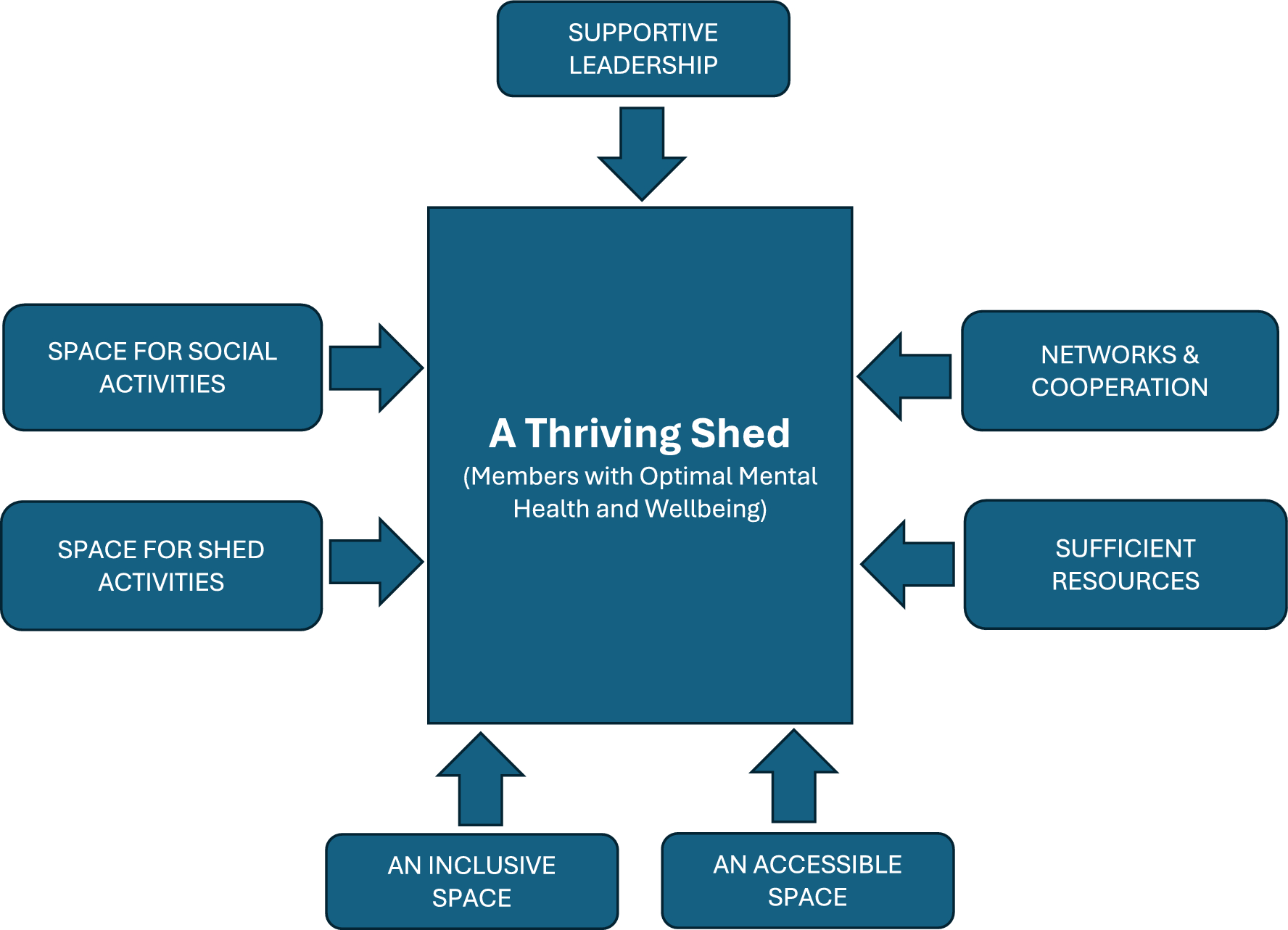

As noted above there has been limited theory developed in relation to membership associations (Tschirhart & Gazley, Reference Tschirhart and Gazley2014). The theoretical framework for this study has been derived from the factors identified in the literature review as impacting on a Shed (e.g. Foettinger et al., Reference Foettinger, Albrecht, Altgeld, Gansefort, Recke, Stalling and Bammann2022). These factors are: flexible and supportive leadership and governance, so that members feel included; sufficient funding and resources to avoid unnecessary pressure on the members; and an appropriate space for both craft and social activities.

These factors are combined with the logic model developed by Kelly et al., (Reference Kelly, Steiner, Mason and Teasdale2019), which identified the key inputs leading to optimal health outcomes for Men’s Sheds. Kelly and colleagues identified these key inputs as: a space for practical/ educational activity, a space for social interaction, and a space that is inclusive and supportive. The practical activities such as woodwork gave the members a reason to attend the Shed but also served as a distraction from any challenges they were experiencing. The space for social interaction enabled the members to interact with each other and discuss personal issues and concerns. It was vital that the Shed was welcoming to all members to ensure that this was a safe space to facilitate this social interaction. Kelly et al.’s inputs overlap with the key themes that emerged from the literature review about there being sufficient space for more than craft activities as well as members feeling included and supported by the Shed leaders.

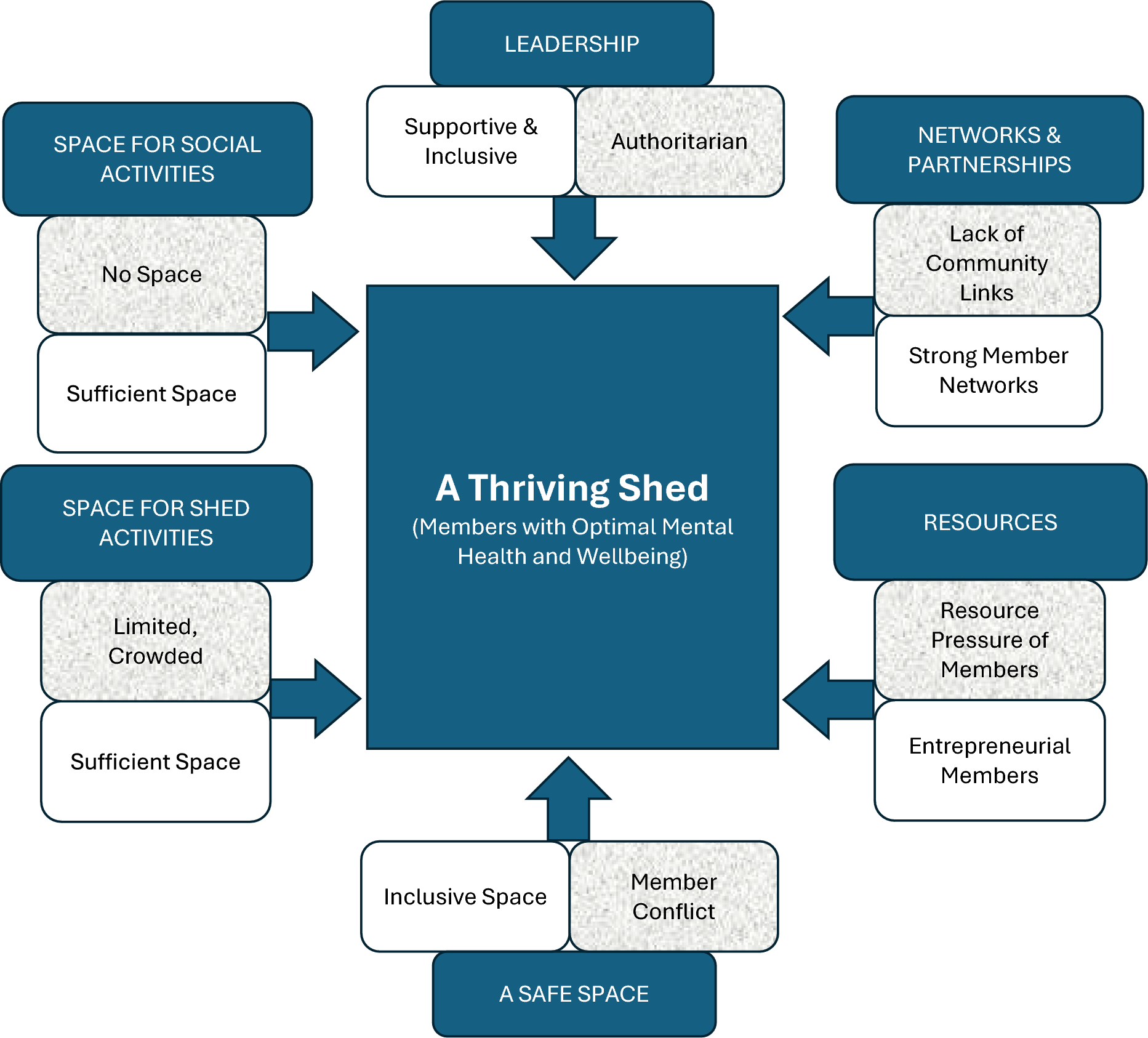

Since Men’s Sheds are voluntary organisations that are run by volunteers for the members, this paper also draws on the concept of recruitability (Haski-Leventhal et al., Reference Haski-Leventhal, Meijs and Hustinx2010), which refers to an organisation’s ability to recruit and retain volunteers. An organisation’s recruitability comprises three components: their accessibility to potential volunteers, the resources that they have available (i.e., financial, human and in-kind), and their networks and cooperation with other organisations, businesses, and governments. Accessibility includes the awareness of potential volunteers about the organisation as well a physically accessible location. Resources refers to sufficient budget and staffing to support the volunteer program. Networks and cooperation are about the ability of the organisation to leverage their formal and informal relationships with other groups and institutions to grow and support their program. The concept of recruitability applies to volunteer organisations with a volunteer manager or coordinator. While Men’s Sheds are membership associations rather than volunteer programs, a thriving Shed’s goal is to recruit and retain members, many of whom volunteer within the Shed. The three components of recruitability overlap with the factors identified in the literature review and Kelly’s model, particularly in relation to the organisations having sufficient resources and networks. The conceptual framework for a thriving Men’s Shed is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 Conceptualising a thriving Shed

Our conceptualisation of a thriving organisation draws on the Thrive at Work framework (Parker et al., Reference Parker, Jorritsma, Griffin, Brough, Gardiner and Daniels2022), which has been extensively used to promote positive mental health in organisations by mitigating illness, preventing harm, and promoting thriving. Promoting thriving is considered to be strategies that aim to enhance active mental health, optimise well-being, and generate future capabilities. The concept of thriving within organisations being operationalised by positive impacts on well-being and mental health is shared across the Thrive at Work framework and this study.

Combining these three perspectives leads us to propose that there are five components that are needed for a thriving Men’s Shed. These are supportive governance, making members feel included, having strong networks, sufficient resources, and sufficient space. This forms a tentative framework to guide data collection in order to answer the research question: What makes a thriving Shed?

Methods

The study sought to investigate empirically what makes a thriving Men’s Shed. The study took place within the pragmatist paradigm as this approach enables the investigation of real-world problems, using a range of data collection methods (Creswell & Plano-Clark, Reference Creswell and Plano-Clark2018). This paper used a series of in-depth interviews (King & Horrocks, Reference King and Horrocks2010) guided by the study’s conceptual framework with committee members from Men’s Sheds in Western Australia. The interviews asked questions about the governance and leadership of the Shed such as leadership style and committee turnover; steps taken to include members; the resourcing of the Shed including funding sources and networks; and the physical structure and layout of each Shed. Each interview participant was also asked about the membership of the Shed, the profile of the members and whether membership was increasing, staying the same or decreasing alongside questions about members’ access to the Shed including opening hours and physical access.

Where possible the Shed President was interviewed but sometimes it was the Treasurer or the Secretary, noting that committee members often move between different roles and have considerable knowledge about their Shed. To select the Sheds included in the study, we sought the advice from the Men’s Sheds WA umbrella organisation about which Sheds were considered to be thriving or in need of support and we contacted each Shed and invited them to participate in the project.

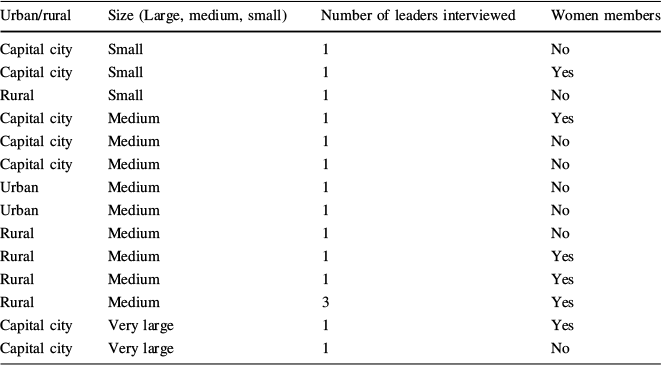

Human Research Ethics Committee approval was obtained prior to commencing the fieldwork from the research team’s university. A total of 16 participants were interviewed at 14 different Men’s Sheds during 2022. The focus of the interviews was on the Sheds rather than the participants, so limited personal data were collected. All participants were older males and retired from paid work, except for one Shed, which is operated by local government and has a paid coordinator. This Shed was included in the study as the one paid staff member is assisted by a Management Support Group of volunteer members. No further demographic data were collected about the participants but they represent the typical Men’s Shed member in Australia (Cavanagh et al., Reference Cavanagh, McNeil and Bartram2013). Table 1 presents information on each Shed, while maintaining their anonymity, as required by the University’s Human Research Ethics Committee. In terms of Shed membership, we classified these as: small with less than 50 members, medium sized with 50–150 members, a large Shed with 150–250 member and a very large Shed having over 250 members.

Table 1 Sheds and their leaders

|

Urban/rural |

Size (Large, medium, small) |

Number of leaders interviewed |

Women members |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Capital city |

Small |

1 |

No |

|

Capital city |

Small |

1 |

Yes |

|

Rural |

Small |

1 |

No |

|

Capital city |

Medium |

1 |

Yes |

|

Capital city |

Medium |

1 |

No |

|

Capital city |

Medium |

1 |

No |

|

Urban |

Medium |

1 |

No |

|

Urban |

Medium |

1 |

No |

|

Rural |

Medium |

1 |

No |

|

Rural |

Medium |

1 |

Yes |

|

Rural |

Medium |

1 |

Yes |

|

Rural |

Medium |

3 |

Yes |

|

Capital city |

Very large |

1 |

Yes |

|

Capital city |

Very large |

1 |

No |

The interviews lasted between 32 and 73 min. Due to the risk of COVID-19 with participants were mostly older and potentially at risk, the interviews were generally conducted using Microsoft Teams. Three of the interviews were conducted by telephone due to technological limitations, such as the lack of internet coverage for rural-based Sheds. The interviews were all recorded and transcribed for analysis. All the participants were sent a transcript of their interview for checking and only one participant sent back some amendments. These amendments were editorial rather than content-based.

The data were analysed using template analysis (King, Reference King, Symon and Cassell2012), supported by NVIVO V.14. Template analysis combines deductive and inductive approaches to data analysis. It is primarily suited to analysing interview data, and its particular strength is its flexibility, allowing the researcher to code both descriptive and interpretive themes (Brooks et al., Reference Brooks, McCluskey, Turley and King2015). First a tentative template of themes is identified from the literature review and conceptual framework and is used to guide first-order coding. In this study, the literature identified funding, leadership, networks, and physical structure and layout as potential key themes. During the second stage of coding, new themes are allowed to emerge inductively from the data and are added to the template. The new themes that emerged were: communication within the Shed, how far Shed members had input into decisions about the activities of the Shed, and the support that the Shed provided to members. The coding was completed by one researcher and checked by a second researcher from the team. The final template is used to answer the research question ‘what makes a thriving Men’s Shed?’ and the themes are presented below in the findings.

Findings

The Men’s Sheds that participated in the interviews represented a diverse range of Sheds, see Table 1. Seven Sheds were located in Perth’s metropolitan area; two in large regional towns; and five were located in small regional towns. In terms of size, the Sheds ranged from 25 to 250 members and the age of the Sheds varied between two and sixteen years old. There was enormous variation across the Men’s Sheds in terms of their membership, resourcing and networks, which impact on their ability to operate and offer activities to their members. The Shed activities most commonly included woodwork and metal work but also beekeeping, gardening, photography, cookery, and walking groups. Three Sheds included women members, and at a further two Sheds women could join in the activities but not join as a voting member.

The findings also revealed two distinct groups of Sheds within the sample, namely, large metropolitan Sheds and smaller regional and rural Sheds. The regional and rural Sheds played an important role in their communities, supporting other groups and associations, which may not be needed so much in metropolitan areas. The findings are presented thematically, using the four main themes that emerged from the data: Leadership and Governance, Inclusion, Networks, Resources, and Space.

Leadership and governance

The literature talks about the importance of the leadership style in making members feel welcome. Several Shed leaders talked about how they sought to keep the balance between having the ‘right’ atmosphere with getting things done for the Shed needs, with one Shed commenting that they have “never allowed anyone to be dominant…otherwise you’d end up with no members…”. Another Shed leader commented “I’m not an empire-builder, I’m here just to serve the members,” and stated that they were willing to drop a proposed change for the benefit of the Shed, if it made the members feel uncomfortable.

Several Shed leaders raised the importance of communicating regularly with members using a wide range of methods including email, newsletters, and regular coffee mornings or in emergencies, for example, when the Shed shut down due to COVID-19, via text message. The Sheds all sent out the minutes for more formal meetings to the wider membership, “All the minutes…go to every member … Everybody needs to know everything.”

A key component of the leadership style at the Sheds was how far ordinary members had input into decisions impacting the Shed such as deciding on new activities. Most Shed leaders commented that anyone could attend regular committee meetings and provide input. Generally, the activities available depended on the Sheds resources and members’ willingness to organise them. While larger Sheds were generally able to offer more activities because they had the members and space to support these, some of the smaller rural Sheds also offered their members a diverse range beyond woodwork and metalwork. One of the largest Sheds in the sample commented that:

I think our Shed works because we do have 10 or 12 quite diverse groups operating out of this. So there’s lots of things you can try. You can try singing, you can try cooking. You can try wood turning, don’t have to do woodworking, go into the garden, and we have several members who come who have early dementia or Alzheimer’s, but they can do a little bit of watering of plants and things, quite safe activities. So, we opened the Shed to just about everyone. With differing abilities in quite diverse way.

This reflects the need for large Sheds to seek to share the workload through delegation and highlights that some Sheds could be too successful to attracting new members.

Inclusion

A Men’s Shed is a mutual-aid membership association, and the Shed leaders all talked about the importance of supporting their members. All but one of the Sheds had a stable or increasing membership base. There was some concern about the age profile of members and how to attract younger members. The Shed leaders commented that there was a general perception that you need to be old but not too old to be a Men’s Shed member.

Men’s Sheds have been encouraged to broaden their membership by the umbrella association to include women and younger members but only two of the Sheds had female members and there was clearly some tension between the original mission of supporting men’s health and being more inclusive. While Sheds were encouraged to increase the diversity of members to become a more inclusive, this could also ensure the longer-term viability of Sheds by having a wider potential membership pool.

The encouragement to include women members was met with varying responses. Some Sheds chose to run a combination of men-only, mixed and women-only sessions, while others had voted against including women in what was perceived as a safe ‘male’ space:

“…we can’t be men when we’ve got women around like I said the language and the jokes going on between men and yourself you know what would happen, and uh, we just would feel uncomfortable having women here.”

There were also practical concerns that the facilities at the Shed, such as toilets, would not be suitable to women members.

The Shed leaders appeared very aware of their pastoral role with their members. One Shed leader described a thriving Shed as “…one that's inclusive. And …cater to the differing needs of its members. And give support to the members as they, inevitably, go through whatever life changes.”

Another Shed keeps a register of attendees and calls if someone misses two weeks in a row to check on them, although they stated that it was hard to know who should take on this pastoral role. While not directly related to health outcomes, many Sheds felt that their role was to help their members lead independent lives as they aged. This included teaching how to cook simple meals—and clear up afterwards—or classes on internet banking, which has become more important as banks close their branches in rural areas.

The Men’s Sheds in regional or rural towns acted as a community centre, providing a meeting place, coffee, or breakfast for other groups, for example, “we’re open to everyone and anyone… We’ve had a few people… pop in as they’re doing a trip around [Western Australia], so yeah we put out a bit of a spread for them”.

Networks

Networks included both formal and informal partnerships with a wide range of organisations including local government, clients, businesses, and other community and non-profit groups. In some cases, these provided mutual support while others were transactional. The interviews revealed the importance of partnerships in both establishing the Shed initially and in maintaining its viability. A number of Sheds grew out of Rotary Clubs, who acted as sponsors. This is intriguing as Men’s Sheds could be considered a competitor for Rotary, as an alternative membership-based group. However, this highlights the differences between the aims and activities of the two movements.

While the Sheds’ relationships with their local council varied, they all recognised the importance of this relationship, with one Shed leader commenting, “…one thing I always say to anyone that’s developing a Shed. Make sure you go and introduce yourselves to your politician…” A couple of Men’s Sheds have paid staff provided by the local council and posit that this provides continuity and better care for members than the turnover of different volunteer supervisors each shift.

Each individual Shed drew on the members’ networks. For example, one Shed member was a high-level board member at a hardware store and made a substantial personal donation. Another Shed member was a shareholder in a demolition company, which enabled the Shed to access materials and equipment including a full kitchen. Two Sheds had partnerships with a mining company that donated scrap metal and wire, which the Shed cleaned and sold for considerable sums. The value of the Sheds’ networks depended on members’ connections, which included an element of luck or serendipity. Larger Sheds with more members may have greater reach to more networks. Sheds located in wealthier communities might be able to use their networks to access more resources.

Resources

All the Sheds charge membership fees but also received funding from a range of sources. All the Sheds had received grants for capital works from State and local government. The Sheds were successful in attracting substantial grants to expand the Shed facilities, adding in a mezzanine floor or installing equipment, for example. Most Sheds had a member who specialised in applying for these grants. The participants did note that the grant application process was very time consuming and involves too much bureaucracy, with one leader stating that “We’ve given up because it is so difficult to work with the council”. There were also examples of a Shed having to apply for something bigger than what they wanted to meet the grant requirements. For example, one Shed only needed a storage area but included an office space in the grant application to meet the grant program’s parameters.

The Sheds were very entrepreneurial in fundraising. Most Sheds received donations of goods which were usually sold on for profit. Most Sheds also collected for a recycling scheme that provides cash for containers, often serving as the local collection point in their town. They also held fundraisers such as a sausage sizzle in front of the local hardware store (an Australian institution), but these were less frequent. A unique approach from one large Shed, which has several discrete activity groups, is to require each group to break even over the year with their income and expenditure.

Most Sheds did not rely on selling goods as a major source of funding. Selling items at farmers’ markets, for example, was not popular and the Shed leaders commented that members were not particularly skilled at sales. Sheds were more likely to post items for sale on their Facebook page, for example, rather than sell directly. The Sheds also preferred commissions for local schools or community groups. Networks and partnerships with the local council, businesses or other organisations were important in terms of the financial viability of the Sheds and perhaps less transactional than partnerships based around commissions.

Funding is only one Shed’s resources alongside the members who are needed to run the Shed both in leadership roles on the committee and with day-to-day operational activities. All the Sheds experienced challenges in finding committee members, with one president estimating that 20% of members will become active in organising activities: “it’s the same people on the committee and cleaning up and doing stuff like washing towels or vacuuming the floor…”.

While the Shed constitutions require that committee roles are vacated every 1–2 years, often the same people swap around the roles on the committee, with one leader commenting, “…nobody wants to play vice president, I’ve been doing this job for 8 years now and I really need to sort of take a breather…” Another challenge is that members who take on committee roles often have other leadership roles in the community. This is particularly problematic in small communities, with a limited pool of potential volunteer leaders.

Space

The physical structure of each Shed varied, with some Sheds occupying purpose-built buildings, while others have adapted existing structures. Regardless, several Sheds were undertaking building works, or applying for funds to undertake these, to create more workshop space and storage space was at a premium. A good measure of Shed’s size, and whether it met members’ needs, was how many members could use the workshop space at a time. While nearly all Sheds were accepting new members, one Shed leader commented that they could not accommodate all existing members, “…the problem being there isn't enough room or bench space for the fellows to assemble things. And also they [need a certain] amount of space around the machines. So it does get congested.”

This again highlights the risk of a Shed becoming too successful and the need to manage membership to ensure that all members can continue to thrive.

The Sheds generally had workshop space—for both woodwork and metalwork—a quiet area for meetings, and a communal area for tea breaks. This communal area might be a lounge or could simply be the veranda as space for social areas is more flexible than for craft activities. The tea break, where everyone stopped work and came together to chat was an essential part of the Men’s Shed programme. Some Sheds also had gardens, which were used for gardening and beekeeping which expanded the scope of the Shed.

All Sheds were open at set times during the week, and less frequently at the weekend, limited by the need to provide supervision for insurance reasons. Supervision also involved monitoring attendance in case a member might need someone to check in on them, and also about ensuring members felt welcome.

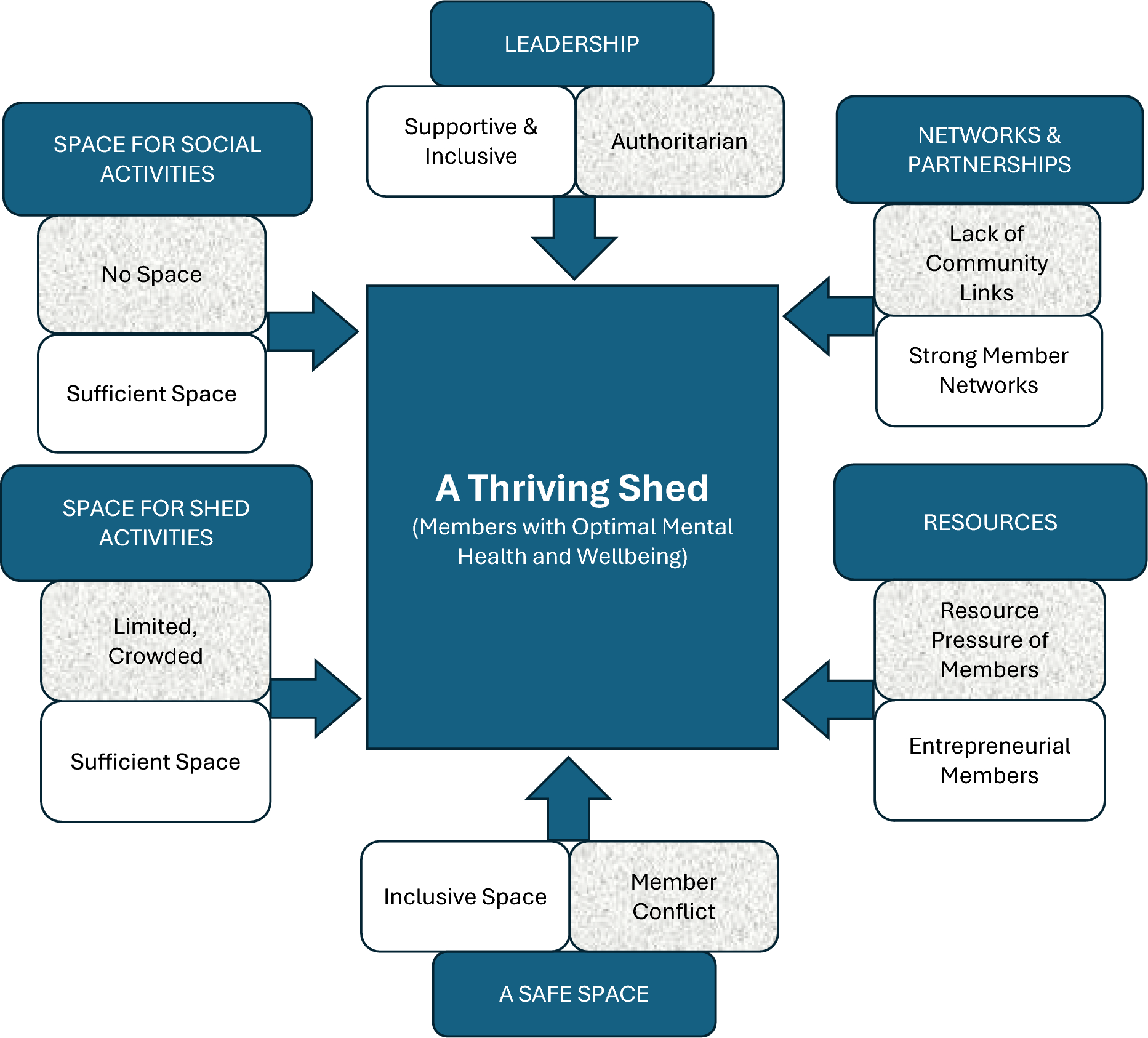

Discussion: What Makes a Thriving Men’s Shed?

The findings explored how the proposed conceptual framework presented in Fig. 1 aligned with Men’s Shed leaders’ perceptions of what makes a thriving Men’s Shed and provides insights for membership associations more widely. The importance of governance in creating a thriving Shed reflects the literature, which noted how too many rules can negatively impact members’ health outcomes (Foettinger et al., Reference Foettinger, Albrecht, Altgeld, Gansefort, Recke, Stalling and Bammann2022; Robinson, Reference Robinson2019; Southcombe et al., Reference Southcombe, Cavanagh and Bartram2015). Foettinger et al. (Reference Foettinger, Albrecht, Altgeld, Gansefort, Recke, Stalling and Bammann2022) also noted that members need to have autonomy over the Shed’s activities, although this was often limited by available resources, particularly Shed space and members willingness to organise activities.

Shed leaders also talked about how they valued their members and sought to support them. Kelly et al.’s (Reference Kelly, Steiner, Mason and Teasdale2019) model emphasised how creating inclusive spaces at the Sheds was essential in enabling members to participate in the health benefits. Shed leaders spoke about the importance of spaces for social interaction, and organised regular social activities such as morning teas, which was supported by Haesler (Reference Haesler2015) who found that a communal area was essential to reinforce the health benefits of a Men’s Shed. While Men’s Sheds specifically aim to improve their members’ health, research on membership of community groups more broadly has identified substantial mental and physical health benefits from improved social connectedness (Haslam et al., Reference Haslam, Cruwys, Haslam, Dingle and Chang2016). These social interactions can also generate social capital (Mutz et al., Reference Mutz, Burrmann and Braun2022), which aligns particularly with the rural Sheds, acting as a community hub for residents and visitors as also highlighted by Waling and Fildes (Reference Waling and Fildes2017). Membership associations are therefore important components of healthy and connected communities.

Men’s Sheds were originally formed to provide health benefits to men (Boucher, Reference Boucher2023). They were being encouraged by the umbrella association to widen both the age range and consider workshops for women. The Sheds included in this study were mostly thriving in terms of their membership numbers and had waiting lists. There was no requirement to diversify their membership for viability. However, most Sheds had considered whether to allow women to join with some having held a member vote. While practical barriers to including women members were mentioned, there were also clear tensions between Sheds role as inclusive community organisations and male-only spaces.

Previous studies about Men’s Sheds have identified that funding and Shed space are critical resources (Kelly et al., Reference Kelly, Steiner, Mason and Teasdale2019; Robinson, Reference Robinson2019). These studies have not considered the vital role of the Sheds’ networks in providing access to these resources such as obtaining local government permissions to extend the Shed. While members were neither keen, nor particularly skilled at selling their wares directly, there were other entrepreneurial fundraising methods used by Sheds. Members both preferred and were better at indirect fundraising. The role of networks in generating support and resources are, however, a key component of recruitability, and were included in the conceptual framework (Fig. 1).

Membership associations rely on their members to volunteer for the organisation, which has received little attention in previous studies. The findings revealed the different ways in which member volunteers can support their Shed as well as challenges for both committee succession planning and engaging members in the running of the association. While succession planning is a common for membership associations (Doherty & Cuskelly, Reference Doherty and Cuskelly2020), the resulting burden of running the Shed falling to same members over many years, could impact negatively on their health and well-being.

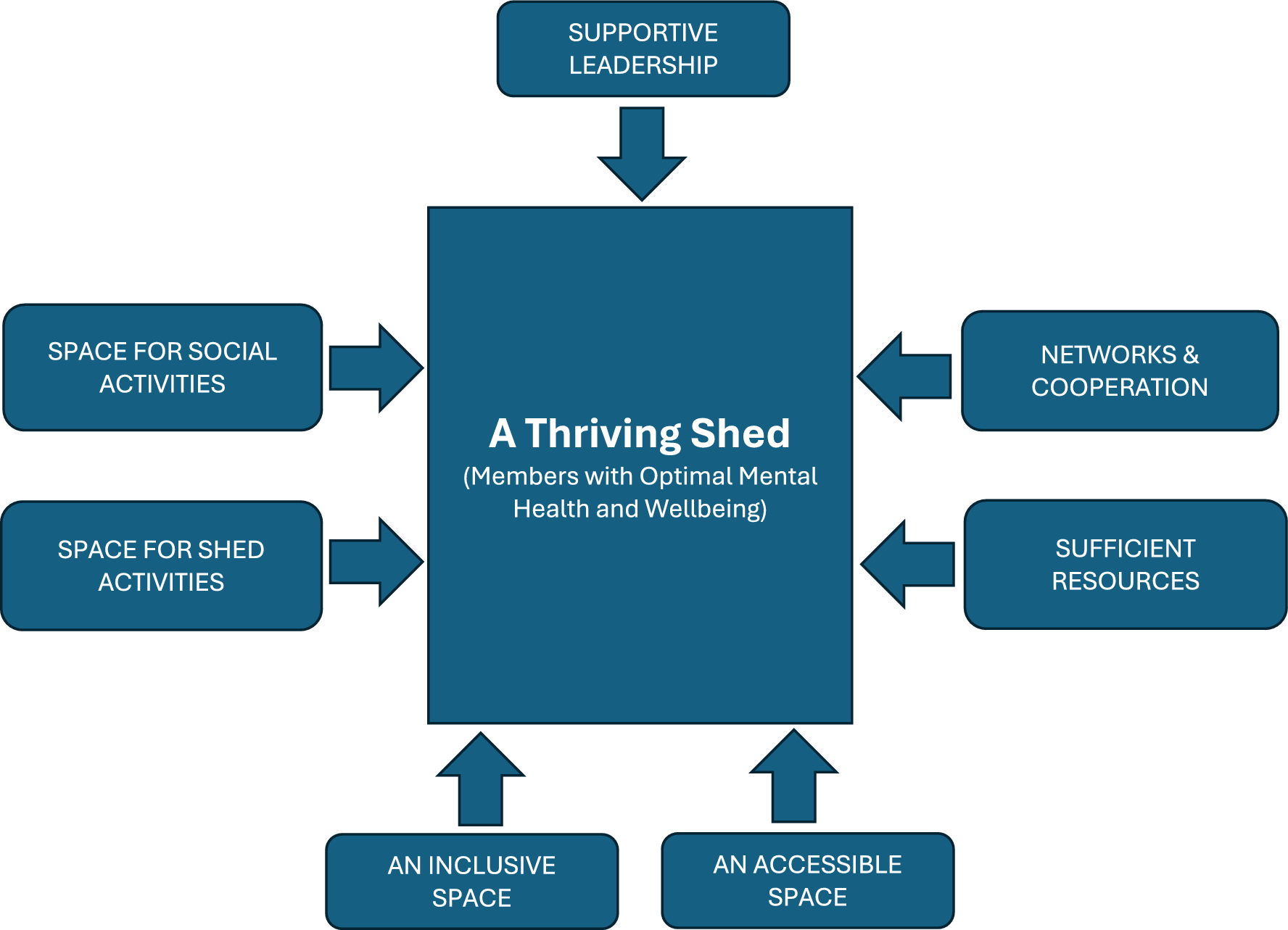

This study expands current research on the Men’s Sheds movement to reveal empirically the factors that contribute to the thriving Shed. Prior research has identified these factors as supportive and inclusive governance, inclusive and adequate space, and sufficient funding. This project combines these factors identified by Kelly et al., (Reference Kelly, Steiner, Mason and Teasdale2019), Foettinger et al., (Reference Foettinger, Albrecht, Altgeld, Gansefort, Recke, Stalling and Bammann2022) and others with the concept of recruitability to add the role of networks. Our initial conceptual framework was presented in Fig. 1. The data revealed the critical role and associated challenges of members as volunteers in supporting the Shed. The final framework is presented in Fig. 2 and amended the accessible space to be a ‘safe space’ and ‘networks and cooperation’ to be ‘networks and partnerships’ as this better reflected our findings.

Fig. 2 A thriving Men’s Shed. Shaded boxes are detrimental and unshaded boxes are helpful

Conclusion

This paper reports on the qualitative component of a mixed methods study with Men’s Sheds in Western Australia that aimed to identify what makes a thriving Men’s Shed, drawing on the idea of thriving organisations. The findings reveal both the diversity of Men’s Sheds and the similarities in their operations. The Sheds were all entrepreneurial and fairly successful in applying for and attracting grants. They had developed strong networks within their communities, which help with resourcing. The two biggest challenges were identified as the limitations of their building—particularly in having sufficient workshop and storage space—and in getting more members involved in the running of the Shed, including taking on committee roles.

The study proposed a conceptual framework for what makes a thriving Men’s Shed. The framework was explored empirically within the data and comprises: supportive governance, making members feel included, having strong networks, sufficient resources, and sufficient space. Overall, Men’s Sheds needed to be inclusive spaces that gave members freedom and choice over how they engaged with the Shed, its activities, and each other. However, there were tensions over how inclusive these spaces could be when the Sheds were encouraged to diversify their membership.

The findings have important implications for practice as they offer a checklist of factors for Men’s Sheds to review how they are serving their members and identify areas of concern. This checklist could be developed into an online tool to assist Shed leaders in evaluating how their Shed is meeting their members’ needs.

Limitations and Further Research

We acknowledge the limitations of this study, which are due to the small number of Sheds and the geographic scope of the project. The study also only interviewed the Shed leaders rather than a cross section of members although we found considerable consensus among the data. Further research could include Shed members and compare the findings with other states around Australia and internationally. In particular, the model could be examined in the context of Sheds that have limited access to the components of our model and struggle to thrive. Future studies could also explore the tensions in expanding the membership to include women.

The findings have the potential to be useful for a wide range of membership associations including sports clubs, ‘friends of’ groups, grassroots associations, and other mutual-aid membership associations. Future research could apply this framework across different membership associations to test the transferability of the findings.

As the Men’s Sheds movement continues to grow, it is timely to review the factors that have enabled Sheds to thrive now and in the future.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and data analysis were conducted by Kirsten Holmes, Peter McEvoy, James Clarke, and Briana Guerrini. James Wild, Jaxon Ashley, and Rebecca Talbot recommended research participants, and reviewed the findings and the conclusions. The literature review was reviewed by Briana Guerrini. Manuscript preparation was led by Kirsten Holmes.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. The research leading to these results received funding from Men’s Sheds WA and Lotterywest.

Data Availability

The data were collected with approval from the Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee, and all interview participants provided formal informed consent through a signed consent form, having received a participant information sheet, following the guidelines of the (Australian) National Statement on Human Research Ethics, 2007, https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/national-statement-ethical-conduct-human-research-2007-updated-2018.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.