Background

Food insecurity, defined as the condition of lacking access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food to meet basic dietary needs, remains a significant global public health challenge without borders(1). It affects people from all walks of life and cuts across cultures and all levels of economic development. Its causes and consequences are deeply rooted in the legacy of colonialism and colonial policies(Reference Friesen2–Reference Amartya and Tinker5). Arbitrary colonial borders disrupted local economies, agricultural practises that governed food production and land management and traditional resource-sharing systems. Global conflicts have further enabled transnational corporations (TNCs) to exploit these disruptions by creating and monopolising new food markets through control of key resources(Reference Friesen2,Reference Amartya and Tinker5) .

Available data indicate that the world produces enough food to feed everyone on earth. The global primary crop production reached 9.6 billion metric tonnes (valued at United States Dollar (USD) 2.9 trillion to feed 7.99 billion people in 2022)(6). This translated into 1.2 metric tonnes or 1202 kg of primary crop per capita per year or 3.3 kg of primary food per capita per day. Yet, about 757 million people or 9.4% of the world’s population are undernourished. They consume less than the FAO minimum requirement of 1800 kcal per day(7). In addition, 2.33 billion people (28.9%), or more than one in four globally, are moderately or severely food insecure(7).

The unequal distribution of, and inequitable access to, available food is largely driven by TNCs and foreign governments that control global food systems and supply chains(Reference Keenan, Monteath and Wójcik8). This power imbalance fuels land expropriation, driven by insecure tenure and land grabbing enabled by corrupt governments in low- and middle-income countries and their lack of accountability. It causes loss of livelihoods, forced displacement and increased conflicts(Reference Keenan, Monteath and Wójcik8–Reference Yang and He18). Profits are often prioritised over human nutrition. Environmental consequences include deforestation, habitat loss, water degradation and the erosion of biodiversity and ecosystems(Reference Keenan, Monteath and Wójcik8–Reference Yang and He18). Therefore, the aim of this review is to examine why cultural food security and cultural food sovereignty should be prioritised and embedded within conventional food security frameworks. It seeks to demonstrate how culturally grounded, community-driven approaches foster more just, sustainable and empowering food systems for ethnically diverse, Indigenous and local communities, while highlighting the limitations of conventional metrics that overlook socio-cultural, political and ecological dimensions essential to resilience.

Conventional food security

Concerns about the population growth unavoidably superseding food production in the 18th century increased the urgent need to acknowledge food scarcity as a threat to population wellbeing(Reference Malthus19). These concerns were further exacerbated by several significant famines in the 19th century (e.g., the 1845–1852 Great Famine in Ireland as well as famines in India, Russia and China) and the aftermath of World War I and II in the 20th century(Reference Simon20). By 1930s the concept of food for health was floated. The League of Nations’ first account of acute food shortage to characterise the extent of hunger and undernutrition in the world was the focus of its first report on the world food problem(Reference Simon20). As Simon(Reference Simon20) notes: ‘in the early 1930s, Yugoslavia [as a member of the League of Nations] proposed that in view of the importance of food for health, the Health Division of the League of Nations should disseminate information about the food position in representative countries of the world. Its report was the first introduction to the world food problem into the international political arena’ p. 10.

Consequently, an urgent call to establish an organisation to coordinate food security efforts gained momentum. FAO was created in 1945 with its primary objective being to end world hunger and promote food security(Reference Simon20,Reference Phillips21) . One of its challenges was to figure out what, conceptually and operationally, food security really meant. From its formation until the 1970s, the focus was on post–WWII reconstruction and hunger relief(Reference Pernet and Ribi Forclaz22). For example, between 1948 to 1951, the United States provided USD 13.3 billion in economic aid to Western Europe countries devastated by the second world war under the Marshall Plan (US foreign aid for the European Recovery Programme after the WW II)(Reference Nowak23,Reference De Long and Eichengreen24) . More than 60% of the economic aid was spent on food and production expansion such as feeding programmes, agricultural and industrial production including fertilisers, industrial materials and semi-finished inputs(Reference Nowak23,Reference De Long and Eichengreen24) . Between 1960 and 1970, USD 423 billion were spend on development assistance by the Development Assistance Committee countries, which increased by USD 1065 billion in the years 2001–2010(Reference Nowak23).

Over decades, FAO trajectory increasingly aligned with a modernisation paradigm based on agricultural intensification and technology transfer(Reference Pernet and Ribi Forclaz22). The modernisation of agriculture was at the centre of food production thinking, with small-scale and peasant farmers perceived as a hindrance to development(Reference Simon20,Reference Phillips21) . To fund development projects, Western science and technology were prioritised, favouring export-oriented, large-scale production over small-scale rural livelihoods to generate cash-crop profits for global markets and reconstruction efforts(Reference Simon20,Reference Pernet and Ribi Forclaz22,Reference Fan, Rue, Gomez y Paloma, Riesgo and Louhichi25) . Therefore, drawing from neoliberal, individualistic approaches, food security in the late 1960s was conceptualised as having sufficient food availability via domestic production, international markets and price stability at national, regional and global levels. The 1974 World Food Conference defined it as the ‘availability at all times of adequate world supplies of basic food-stuffs, particularly so as to avoid acute food shortages in the event of widespread crop failure, natural or other disasters, to sustain a steady expansion of food consumption in countries with low levels of per capita intake and to offset fluctuations in production and prices’ p. 14(26).

In 1983, the FAO revised its definition to include household- and individual-level access, moving beyond national food stocks. It highlighted that food security depends not only on availability but also on access shaped by socio-cultural, legal, political and economic factors, stating that ‘the objective of world food security should be to ensure that all people at all times have both physical and economic access to the basic food they need’ p. 6(Reference Malthus19). These definitions, however, did not include food utilisation, which is influenced by complex factors(Reference Renzaho and Mellor27). Physical factors include lack of cooking fuel and equipment, inadequate storage, food spoilage and limited cooking skills. Biological factors include illness affecting nutrient absorption or appetite, and nutrient loss through improper preparation(Reference Renzaho and Mellor27).

Consequently, the 1996 World Food Summit in Rome revised the definition to introduce elements of food utilisation: ‘when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life’ p. 1.(28). In 2001, the definition was further refined to include social dimensions food utilisation: ‘a situation that exists when all people, at all times, have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life’ p. 49(1). Therefore, these last two definitions introduced the four pillars of food security(Reference Renzaho and Mellor27,29) . Availability denotes enough quality food supplied via domestic production, imports, or food aid. Access denotes individuals having the resources including entitlements and supportive legal, political, economic and sociocultural arrangements to obtain nutritious foods. Utilisation characterises effective food use, supported by cooking skills, diet, clean water, sanitation and health care. Stability denotes populations, households, or individuals maintaining access to adequate food at all times, without resorting to unhealthy coping strategies during shocks (e.g., economic or climatic crises) or cyclical events (e.g., seasonal food insecurity)(Reference Renzaho and Mellor27,29) . Nonetheless, despite growing recognition of broader aspects of food security, recent policies and research still prioritise production expansion and technological innovation, often overlooking environmental impacts, equity and long-term sustainability. These approaches focus on yield gains and farm efficiency as the primary strategies to ensure food availability(Reference Friesen2,Reference Sodano30–Reference Islam33) .

Philosophical underpinning of conventional food security

The definition of conventional food security, although comprehensive, is founded in neoliberal ideas (i.e., market logics, individualism and global competitiveness socially constructed and institutionally reinforced through state-sponsored discourse and practise)(Reference Friesen2). Neoliberal philosophical approaches are shaped by individualistic values. Such values make it difficult to operationalise food security interventions and measure their impact in mainly collectivist societies(Reference Singelis, Triandis and Bhawuk34), which are disproportionately affected by global hunger and food insecurity. Such individualistic values are unsustainable and rely on unjust corporate pathways to food systems. The focus has been on biotechnology to improve crop traits such as higher crop and livestock yields, improved nutritional content and safety, resistance to diseases, pests and environmental genetics such as crops tolerant to environmental shocks linked to drought, heat or salinity(Reference Hamdan, Mohd Noor and Abd-Aziz35–Reference Eskandar37). Biotechnology has also been used to promote organic biotechnology, including microbial biotechnology biopesticides (e.g., natural pesticides derived from microorganisms), biofertilizers (e.g., harnessing microorganisms to enhance nutrient availability in the soil and improve plant growth), plant biotechnology (e.g., tissue culture to create new plant varieties from plant cells or tissues) or animal biotechnology (e.g., artificial insemination that uses sperm from selected sires to improve livestock breeding or transplanting embryos from high-quality animals to others)(Reference Maddela and García38–Reference Eid, Fouda and Abdel-Rahman40).

TNCs threaten national sovereignty by influencing domestic policies and markets through land foreignization, such as large-scale land acquisitions or ‘land grabbing’, which disincentivises local production and restricts communities’ access to productive resources (Figure 1)(Reference Sonno and Zufacchi41–Reference Castet44). They undermine national autonomy by shaping production, trade and land-use decisions to favour foreign interests. Dependence on imports, foreign aid and externally controlled resources weakens self-sufficiency, leaving countries less able to meet their own food needs independently(Reference Sonno and Zufacchi41–Reference Castet44). Individualistic and corporate pathways to food systems are profit driven and position economic growth as the primary vehicle for achieving food security objectives. Hence, they prioritise market-based mechanisms, promote private ownership and technological innovation, and emphasise the agency and personal responsibility for food access and utilisation. Free markets, agency and responsibility, and privatisation and deregulation as the main tenets of neoliberal economic policies fail to recognise systemic inequities and barriers linked to interdependent and hierarchical values of foodways (i.e., deeply rooted cultural practises, beliefs, and norms that guide how communities grow, prepare, preserve, share, and consume food, reflecting collective identities, social relationships, and intergenerational knowledge(Reference Brellas and Martinez45)). The Thatcherism and Reaganism’s political philosophies in the 1980s were true examples of neoliberal policies that embraced such principles and continue to dominate the current discourse on eliminating hunger(Reference Béland46,Reference Lockie, Goodman, Marsden and Murdoch47) . Consequently, food has been an economic commodity with significant implications for global trade and economic stability that far outweigh the primary socio-cultural and nutrition objectives of food security interventions.

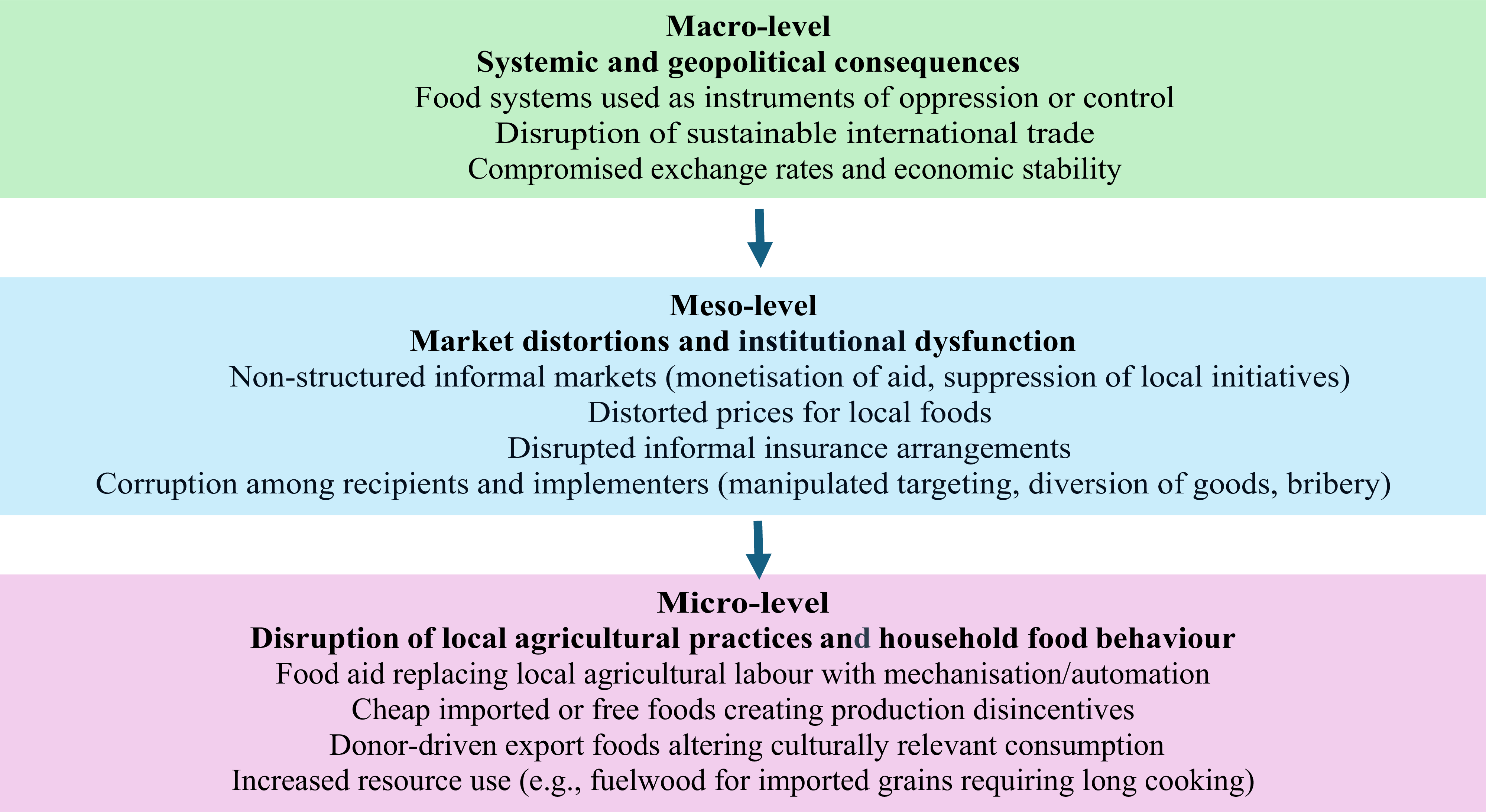

Figure 1. Neoliberal approaches to food security.

TNCs maximise profits through mass production, monocultures, and biotechnology at the expense of indigenous agricultural knowledge and agroecological systems(Reference Friesen2,Reference Shiva48,Reference Çelik49) . Land grabbing, as an example, disproportionately affects countries and regions that bear the highest burden of food insecurity. Recent estimates by Sonno and Zufacchi(Reference Sonno and Zufacchi41) indicated that globally, direct foreign investments in primary sectors consistently recorded 10% yearly growth between 2000–2017, translating into a peak of $15 billion in 2015. These global foreign investments have primarily been long-term acquisitions or leasing of agricultural land. Over 80 million hectares of land were acquired in 2023 globally through public large-scale land deals, representing 5.8% of the world’s arable land(Reference Sonno and Zufacchi41). The authors estimate that the number of large-scale land contracts increased by 128% between 2012 and 2024.

Barrett(Reference Barrett50) argues that neoliberal philosophical approaches affect states at three levels (Figure 1 ). At the micro-level, food aid programmes impair agricultural practises. TNCs’ policies impact household labour supply (e.g., agricultural labour replaced with mechanisation and automation or free foods making people lazy), favour production disincentives (e.g., imported cheap ultra-processed foods or free food aid distorting local food trading dynamics), alter food consumption patterns (e.g., donor-oriented export promotion of foods with little local and cultural relevance), and increase the erosion of natural resources (e.g., importing or the provision of whole grains requiring long cooking times thus the need for more fuelwoods that stimulate local deforestation). At the meso-level, consequences included non-structured informal markets (e.g., monetisation of free food aid or suppression of local initiatives by TNCs), distorted market prices (e.g., fall in prices for locally produced foods), disruption of informal insurance arrangements, and corruption among recipients (e.g., payments to induce fake inclusion to inflate beneficiary status, pressures on beneficiaries to accept sub standards services, and interference with targeting criteria where those with high needs are left out all together) and implementers (e.g., diversion of goods, manipulation of targeting, unethical procurement practises, and extortion and bribery). At the macro level, unintended consequences include international food systems being used as an instrument for oppression and violence, disrupted sustainable international trade, and compromised exchange rates.

Neoliberal governance of global food: TNCs’ monopoly and structural adjustment programmes

Increased food production as the major objective of food security programmes became the cornerstone of the Green Revolution (1960s–1980s), with an emphasis on technology transfer from high-income to low-and-middle income countries(Reference Khush51–Reference Pray53). During this period, corporate-led agricultural modernisation emphasised and promoted food production efficiency. High-yield seeds, the use of chemical fertilisers and mechanisation dominated the food security discourse. By making farmers dependent on purchased inputs and externally controlled supply chains, TNCs along with their backers and support subsystems monopolised and took over the control of food production systems and the global supply chain(Reference Friesen2,Reference Çelik49) . They controlled the distribution and retail of farming inputs and resources such as irrigation systems, high-yielding crop varieties, fertilisers and pesticides, machineries, fuels and lubricants, labour and other materials and tools critical to farming infrastructure. The economic access dimension was integrated into the World Trade Organisation’s policies and the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank’s structural adjustment programmes(Reference Friesen2).

For example, structural adjustment programmes pushed for reduced government subsidies such as those related to the provision of fertilisers and the liberalisation of land tenure and markets(Reference Lele54). Land tenure liberalisation prioritised reforming land ownership and access policies and regulations to stimulate private or foreign ownership in increasingly market-oriented agricultural environments(Reference Lele54). Imposing economic structural adjustment in low-and-middle income countries to stimulate their international competitiveness favoured policies geared towards trade liberalisation and opening up of agricultural markets to TNCs and global agribusiness organisations(Reference Lele54). Consequently, local food self-sufficiency or simply local food security became compromised as food security was tied to global commodity markets and foreign investments(Reference Friesen2,Reference Lele54) . Austerity measures and market-oriented reforms led to increased food prices, displaced smallholder farmers and reduced government spending on social programmes, hence collectively worsening food insecurity(Reference Sonkin55).

Neoliberal governance of global food: food loss and waste

The prioritisation of market-oriented policies considers food as a commodity and agriculture as solely a mechanism for profit maximisation. Upstream market-oriented food processes produce food waste(Reference Cherrier and Türe56,57) . Food value chains aligning agricultural production and post-harvest processes with market demands to maximise profits lead to inequities in food access(Reference Cherrier and Türe56). Approximately 40% of the world’s food supply (2.5 billion tonnes) goes to waste annually(58). Affluent nations that account for most of the land grabbing in low-and-middle income countries waste more than 59 million tonnes of fresh mass (around 132 kg of food waste per inhabitant)(57). Households account for 54.5% of food waste (32 million tonnes or 72 kg per inhabitant). The remaining 45.5% of food wastes are generated through food supply chains (manufacture of food products and beverages: 18.9% or 11 million tonnes, restaurants and other food services: 11.4% or 7 million tonnes, retail and other distribution of food: 8.3% or 5 million tonnes, and primary production: 7.6% or 4.8 million tonnes)(57). In addition, approximately 30% of the world’s agricultural land (1.4 billion hectares) are used to produce food that is never eaten(59). Halving food waste would potentially increase food availability by 1300 trillion kcal per year by 2050. This increase would represent 22% of the estimated crop production increase required to meet food demands due rapid population growth in 2050, hence lift out of undernutrition the estimated 757 million people experiencing hunger worldwide(Reference Chen, Chaudhary and Mathys60).

Neoliberal governance of global food: food distribution inefficiencies

The neoliberal governance of global food causes unequal access to food and food distribution inefficiencies. The prioritisation of market-oriented policies discourages all forms of state intervention, which significantly affects food distribution due to logistical challenges linked to poor roads or extreme weather conditions, economic shocks and market dynamics. For example, neoliberal governance of the global food system concentrates power in the hands of TNCs and land-acquiring states with the capital, infrastructure and logistical capacity to dominate production and trade(Reference Keenan, Monteath and Wójcik8,Reference Müller, Penny and Niles42,Reference Castet44) . Such entities have greater capacity to easily move food products across borders and take advantage of lower production costs in low- and middle-income countries. These entities have transportation networks that allow them to efficiently move food products from production to consumption, giving them an advantage over local producers and markets(Reference Keenan, Monteath and Wójcik8,Reference Lee, Gereffi and Beauvais10,61) . Free markets and deregulation, central to neoliberal food governance, have been linked to civil strife and conflict(Reference Demmers, Fernández Jilberto and Hogenboom62–Reference Bekele, Drabik and Dries64). TNC-driven land disputes exacerbate resource scarcity, often resulting in violence, evictions and the dismantling of traditional social structures(Reference Serrano-Bosquet and Acebo-Gutiérrez17,Reference Castet44,Reference Bekele, Drabik and Dries64) . These processes heighten alienation and weaken community cohesion, facilitating mobilisation for protests, riots and political defiance(Reference Demmers, Fernández Jilberto and Hogenboom62–Reference Bekele, Drabik and Dries64), which in turn disrupt local systems, food distribution and storage infrastructure, including refrigeration and other facilities critical to post-harvest storage and supply resilience(Reference Weldegiargis, Abebe and Abraha65,Reference Muhyie, Yayeh and Kidanie66) . Collectively, these factors reduce access to essential resources and undermine effective, equitable food distribution.

Neoliberal governance of global food: land grabbing

The main drivers of land grabbing have been complex and multidimensional. Consistent with neo-liberal approaches, land-grabbing is driven by export-oriented agricultural expansion including industrial-scale agriculture for food crops (e.g., cereals) and cash crops (e.g., soy, palm oil or sugarcane). For example, local communities have limited access to the produced food, as 60% of all crops grown on land acquired by TNCs and foreign governments are meant for export markets(16). TNCs and foreign governments acquire land for biofuel crops such as jatropha or sugarcane and the expansion of renewable energy infrastructure (e.g., wind and solar farms)(Reference Canfield, Webster, Gupta and Ambros67). A significant portion of the acquired land is used for timber and forestry businesses(Reference Yang and He18). Such businesses encompass forestry, wood and timber industry and logging concessions or tree plantations to manufacture and sell primary (e.g., lumber of sawed timbers, logs or round woods, woodchips and veneer) and secondary (e.g., rubber, furniture, papers, engineered woods like plywood or particleboard, cabinets, countertops or pallets) wood products. Mining and extractives have also driven land grabbing(Reference Geenen, Hönke, Ansoms and Hilhorst13). Extractions of natural resources from the earth have included minerals, metals, fossil fuels (e.g., such as coal, natural gas and oil) and other materials. TNCs and foreign governments use grabbed land for financial speculations(Reference Dell’Angelo, Rulli and D’Odorico12). In countries with weak institutional and regulatory frameworks, corrupt practises and underdeveloped land markets, cheap lands are acquired as an asset at lower prices. Such lands are used for future resale or investment securities, improved for infrastructure and tourism, or used as to mitigate the negative impact of climate change and to meet the need of carbon markets.

Most of the land grabbing transactions lack transparency, violate human rights and occur without proper consent of land holders(Reference Yang and He18). They prey on customary and communal land tenure, ownership and usage systems. In such land tenure systems, most land rights are governed by local community customs and practises with limited formal titling. The lack of formal documentation or titles leads to land rights insecurity, difficulties in implementing land reforms due to complex and multidimensional customary systems, weak land administration and political obstacles, and challenges associated with accessing credit, investment, or legal protection(Reference Slavchevska, Doss and De La O Campos68–Reference Chimhowu71). Therefore, the impacts of land grabbing are immense and include large scale environmental damages such as deforestation and the loss of biodiversity, displacements of indigenous and local communities, loss of livelihoods for smallholder farmers, and increased conflicts and social unrest(Reference Slavchevska, Doss and De La O Campos68–Reference Chimhowu71). The export-oriented of food produced on acquired land by TNCs and foreign governments reduces diet quality (e.g., import of ultra processed foods), distort local markets, and disrupt trades(Reference Barrett50,Reference Ferrière and Suwa-Eisenmann72) .

Neoliberal governance of global food: health over cultural imperatives

Conventional food security approaches emphasis the food security-health outcome nexus whilst failing to consider local cultures(7,28,73) . There is a clear cultural invisibility. Although culture influences all four pillars of food security, policies often neglect cultural factors, including preferences tied to rituals, gender norms and communal practises(Reference Alonso, Cockx and Swinnen74,Reference House, Brons and Wertheim-Heck75) . Current definitions of food preferences focus narrowly on individual tastes and fail to capture cultural or ceremonial obligations, such as which foods and preparation methods are acceptable during community events, rituals, festivals, or ancestral remembrance ceremonies. Food preferences geared towards satisfying nutrient and caloric needs ignore symbolic and social value of food, and cannot be a substitute for cultural food insecurity and identity loss(Reference Blanchet, Batal and Johnson-Down76). Therefore, there remain two questions that are not answered by conventional food security approaches: 1) how does improving food security address the complex spiritual, cultural and social values embedded in local food systems? and 2) how do food security initiatives threaten state sovereignty and survival and local foodways? Many scholars and civil society organisations have called for culturally attuned food security interventions, hence the rise of ‘cultural food security’ and ‘cultural food sovereignty’ concepts(Reference Power77–79). The differences between these paradigms are summarised in Table 1 and extensively narrated below

Table 1. Multidimensional analysis of conventional food security, cultural food security, and food sovereignty

FAO, Food and Agriculture Organisation; WFP, World Food Programme; WTO, World Trade Organisation; GHGs, Greenhouse Gases; HFIAS, Household Food Insecurity Access Scale; FIES, Food Insecurity Experience Scale; HDDS, Household Dietary Diversity Score; PRA, Participatory rural appraisal.

Cultural food security versus cultural food sovereignty

Numerous civil society organisations and advocacy groups such as La Via Campesina (The Peasant Path), the International Planning Committee for Food Sovereignty, the Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa, or the Alliance of Civil Society Organisations for Sovereignty and Nutritional Food Security have been advocating for cultural food security and cultural food sovereignty to counter the negative effect of conventional food security interventions(Reference Ewing-Chow80,Reference Mingay, Hart and Yoong81) . At the 2024 World Food Day in Rome more than 100 civil society and Indigenous Peoples’ organisations from across the globe came together and released a Manifesto(82). They called for urgent political action to end violence in and weaponisation of global food systems (e.g., using starvation as a weapon of war). The manifesto reaffirmed food as a right and not a commodity. It reiterated the need not to let global corporations and agribusiness organisations govern global food systems with unchecked profits and conflicts of interest that deepen structural inequalities and exacerbate global hunger.

Therefore, simply put, cultural food security is used in the literature to emphasise the right of individuals and communities to access food that is culturally meaningful, tied to identity and prepared using traditional practises(Reference Power77). This definition conceptualises food as being more than sustenance and is closely linked spiritual, social and ecological life. When these cultural dimensions are compromised through neo-colonialist approaches, globalisation, or climate change, then traditional foodways become dysfunctional and lead to cultural erosion and identity loss and ultimately compromised food consumption and malnutrition. According to Power(Reference Power77) cultural food insecurity exists when communities have unreliable access to traditional and local food through traditional harvesting practises. Expanding on this, definition Wright and colleagues(Reference Wright, Lucero and Ferguson83) assert that cultural food security exists ‘when there is the availability, access, utilisation (i.e., food preparation, sharing and consumption) and stability of cultural foods’ p. 702. Cultural food security seeks to answer the question: Do communities have consistent access to food produced using strategies and policies that are respectful of, compatible with, and informed by traditional value belief systems? In this context, food secure communities or individuals are those that have adequate and consistent availability of and access to culturally appropriate food and can participate in food rituals and events as well as social gatherings(79,Reference Patel84,Reference Patel85) .

In contrast, the 2007 Nyéléni Declaration at the first global forum on food sovereignty in Mali defined food sovereignty as ‘the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems. It puts those who produce, distribute and consume food at the heart of food systems and policies rather than the demands of markets and corporations. It defends the interests and inclusion of the next generation. It offers a strategy to resist and dismantle the current corporate trade and food regime’ (p. 9)(79). This definition places local and national economies, markets and empowerment of local farmers at the top of food system priorities and policies at the expense of TNCs. Cultural food sovereignty seeks to answer the question- Do communities have the power to grow, harvest and prepare and share food according to their cultural practises, free from external control?(79,Reference Patel84,Reference Patel85) . In this context, food secure communities and individuals are that have adequate and consistent availability of and access to culturally appropriate food produced, distributed and protected by local food systems they have control over. It emphasises the communities’ rights and power to control local food systems from land to seed to plate, food and agriculture policies, food markets, food production modes, food cultures, women’s rights and natural resources(Reference Patel84). It is deeply rooted in indigenous land right, intergenerational transmission of traditional knowledge, and environmental stewardship to counter the influence and negative effects of industrial and colonial food systems(79,Reference Patel84,Reference Patel85) .

Areas of commonality and differentiation

Cultural food security and cultural food sovereignty are conceptually related and operationally share common features. They only differ in emphasis and depth when examined through the lens of Indigenous communities’ rights, decolonising agriculture and foodways and community autonomy(Reference Patel84). Unlike conventional food security paradigms, which commodify food and uphold the dominance of agribusiness organisations, cultural food security and food sovereignty emphasise local ownership and control, agrarian reform and ecological sustainability(Reference Power77,Reference Patel84) . The primary objective of cultural food security and food sovereignty is to decolonise food systems and restore agency to local communities by global food policies. They offer more holistic frameworks that emphasise self-determination and cultural integrity. Both approaches place culture and local food systems at the centre of food security interventions, emphasising that they are governed by cultural norms and practises (Table 1 ) (Reference Ewing-Chow80). That is, culture governs:

-

1. What food is produced and how and where it is produced. (availability)

-

2. What food is edible, bought, or used in certain cultural celebrations or who controls resources (access)

-

3. The cultural significance of cooking: who cooks, with whom and how food is cooked and consumed (utilisation)

-

4. Eating behaviours and patterns: What constitutes a meal, how to source it over time and when and how frequently to eat it (stability)

Both cultural food security and food sovereignty are tied to cultural foodways and recognise that cultural foodways are shaped by traditions, rituals, value belief systems that dictate how food is produced, prepared and consumed as a way of emphasising cultural identity and connections to a region, time, or group. However, quantitative data on the impact of culture on improving food security outcomes are scarce. The few available data suggest that any cultural agricultural interventions that prioritise farming practises rooted in traditional knowledge and customs among just 25% of the population can have a ripple effect on all the four domains of food security by leveraging the power of social norms and shared values to promote healthier and more sustainable foodways(Reference Ewing-Chow80,Reference Mingay, Hart and Yoong81) .

Individualist versus collectivist views of foodways

The individualism-collectivism continuum theoretical framework(Reference Singelis, Triandis and Bhawuk34,Reference Triandis86,Reference Triandis and Gelfand87) provides an opportunity to understand the influence of culture on all four dimensions of food security (availability, access and choice, utilisation and stability) in terms of food preferences, traditions and behaviours. This theoretical framework sheds lights on cultural differences and the degree to which individuals in a society see themselves as independent or interdependent(Reference Singelis, Triandis and Bhawuk34,Reference Triandis and Gelfand87) . It conceptualises culture as existing on a spectrum, ranging from highly individualistic (emphasising personal goals and independence) to highly collectivistic (prioritising group goals and interdependence)(Reference Singelis, Triandis and Bhawuk34,Reference Triandis86–Reference Hofstede88) . Individualism is informed by human rights principles, which prioritise personal autonomy, freedom of expression and choice and confidentiality and privacy(Reference Freeman89). Individuals’ ability to make independent choices, take responsibility (morally or legally) and enforce self-advocacy and self-determination are highly valued(Reference Freeman89–Reference Renteln91). In individualistic societies, the state has the duty to protect individuals from collective oppression. Individuals express their uniqueness and personal freedom whilst either striving for equality and fairness (horizontal individualism) or acknowledging and valuing hierarchy and competition (vertical individualism)(Reference Singelis, Triandis and Bhawuk34,Reference Triandis86–Reference Hofstede88) .

In contrast, collectivism frames human rights in the context of relationships and social roles, with the emphasis on duties before rights such as individuals’ duty to the family, elders, or a nation(Reference Freeman89,Reference Abadeer and Abadeer90) . Personal agency is relational and individuals’ sense of self and ability to act is significantly dependent on their relationships and connections with others(Reference Freeman89,Reference Abadeer and Abadeer90,Reference Zheng, Xiao and Zhou92,Reference Le93) . That is, decisions are made with consideration for community elders, family and the community at large. Individuals’ choices must align with collective wellbeing. Therefore, collectivism is operationalised through the ‘it takes a village to raise a family’ to emphasise the role of the broader community support (e.g., immediate and extended family, friends, neighbours, teachers and other community members) and shared responsibility in maintaining social order(Reference Wilson94). The emphasis of collectivism is on community, group identity and duties, community obligations and shared hierarchical roles and responsibilities. Individuals either cooperate in their social groups and prioritise group goals (horizontal collectivism) or prioritise the goals of the social group and its hierarchy whilst sacrificing own goals for the benefits of the ingroup (vertical collectivism)(Reference Singelis, Triandis and Bhawuk34,Reference Triandis86–Reference Hofstede88)

Conventional food security represents predominantly individualistic values. It undervalues collectivist food norms, including (Table 2)(Reference Kuhnlein, Erasmus and Spigelski95):

-

Cultural food expressions such as the collective and social (e.g., food as a medium for hospitality or community bonding), meaning rituals and ceremonial practises (e.g., rites of passage or religious rituals), oral traditions and storytelling (e.g., recipe with associated moral lessons), culinary identity and heritage (e.g., food as a living archive of history or ancestral knowledge), symbolism and meaning (e.g., food for fertility or mourning) and power and gender roles (e.g., food preparation and serving roles to reinforce cultural expectations and social hierarchies)

-

Spiritual food expressions such as food as sacred offering, food as divine communication (e.g., food metaphors such as bread of life to symbolise sustenance and divine provision or manna from heaven to symbolise a sudden and unexpected good fortune), ritual fasting (e.g., to purify the soul or seek divine intervention) and feasting (e.g., to celebrate spiritual milestones or divine blessings), dietary laws and sacred restrictions (e.g., Kosher, Halal or Ahimsa), mindful eating and blessings (e.g., reducing food wastage at tables to emphasise God’s blessings and gratitude, or interdependence) and food for spiritual healing (e.g., traditional foods known to have metaphysical properties believed to cleanse, protect or heal)

-

Obscure informal food-sharing systems including non-monetary exchange such as food bartering, gift-giving, labour exchange or social obligations; food sharing as a medium to reinforce local knowledge and norms such as oral traditions, kinship networks or customary rules; and food commensality to symbolise collective identity (e.g., maintenance of rituals or language, family talks, storytelling or collective decision-making), to express both emotional bonds and obligations such as in the case of grief or hardship and emotional solidarity such as to celebrate shared joys or reinforce family honour and loyalty as unspoken rules of conduct, and economic interdependence such as resource pooling and informal safety nets related to child care or elder care

-

Communal resilience mechanisms including mutual aid and reciprocity, extended kinship and networks (e.g., food sharing extends beyond the nuclear family), cultural and spiritual anchors (e.g., shared rituals and food belief system embedded in community support activities during food crisis), communal resource sharing (e.g., food, land, tools, food storage facilities) and community pride and collective memory serving as a motivation to share food and resources

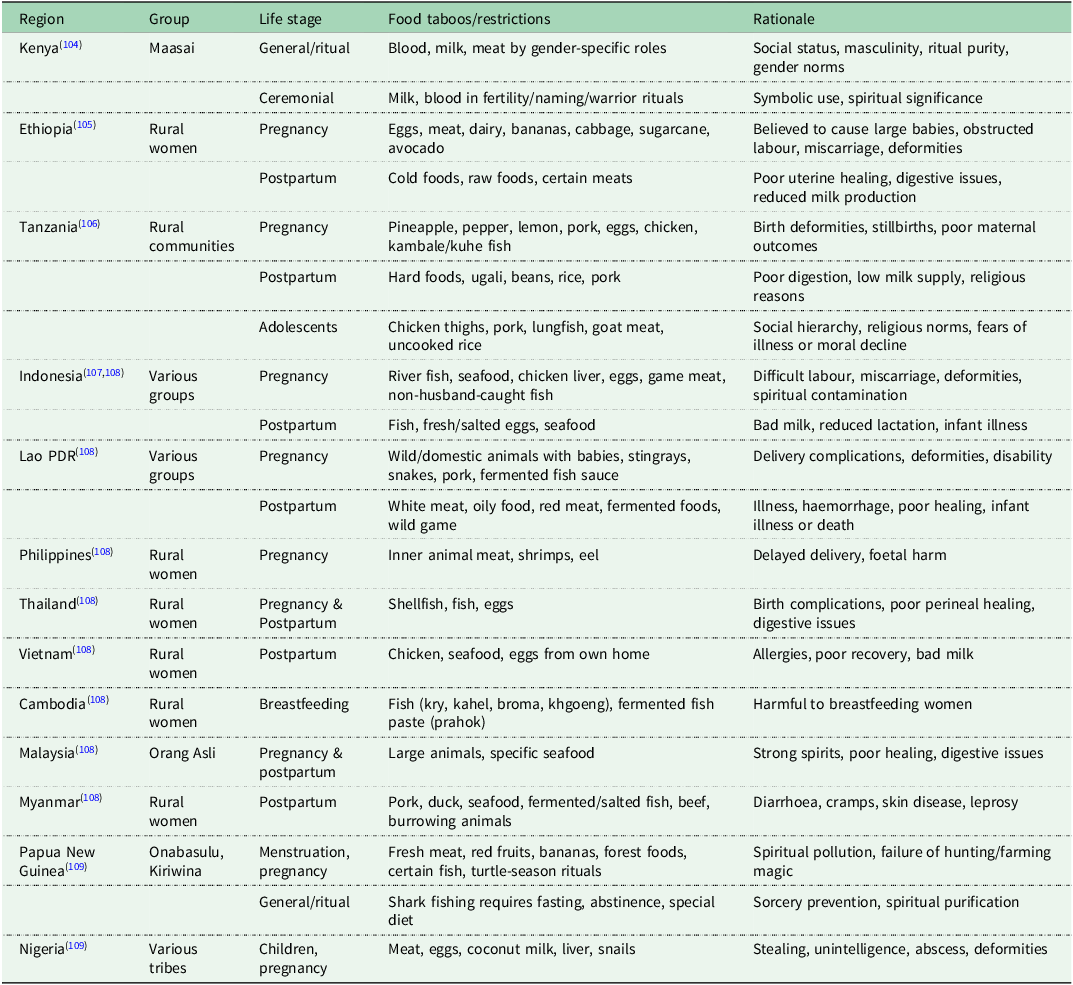

Table 2. Example of cultural taboos and restrictions in collectivist cultures

In collectivist cultures, food and meals are often shared communally, and the symbolic and social significance of feeding outweighs nutritional objectives. Foods may be allocated not simply based on hunger or preference but hierarchically allocated based on gender roles, marital status, age and the occasion. Commensality- the practise of sharing meals and eating together as a social group- is highly valued and affirms social bonds. However, feeding is also governed by food taboos, spiritual restrictions and hierarchical norms.

Food taboos, spiritual restrictions and hierarchical norms affect the most marginalised and vulnerable groups with the highest nutritional needs within households and communities. These food restrictions are gendered and age specific. Food taboos, spiritual restrictions and hierarchical norms vary significantly based on specific contexts, beliefs and practises and are not uniform. They cannot be generalised within and between cultures (Table 2). A systematic reviews by de Diego-Cordero and colleagues(Reference de Diego-Cordero, Rivilla-Garcia and Diaz-Jimenez96) examined the role of cultural beliefs on eating patterns and food practises among pregnant women. Of the 24 studies included in the systematic review, 15 (62.5%) were from the African continent(Reference de Diego-Cordero, Rivilla-Garcia and Diaz-Jimenez96). In a very recent meta-analysis of food taboo practises and associated factors among pregnant women in Sub-Sahara Africa, Belew and collegues(Reference Belew, Mengistu and Lakew97) reported a 41% pooled prevalence of food taboo practises (40% in urban residents and 43% among rural residents). Factors associated with food taboo practises were low level of literacy (being unable to read and write), not receiving antenatal care follow-up and poor maternal nutrition knowledge. Other studies have reported that taboos and food restrictions are intergenerationally transmitted by the family or members of community and are closely linked to a strong religious or spiritual influence(Reference de Diego-Cordero, Rivilla-Garcia and Diaz-Jimenez96,Reference Olajide, Van Der Pligt and McKay98) . When families from low-and middle-income countries migrate to high-income countries, they carry these food taboos and restrictions with them(Reference Olajide, Van Der Pligt and McKay98).

Food taboos and restrictions can act as a barrier to adequate nutrition for children, adolescents and pregnant and lactating women, depriving them with essential nutrients crucial during critical life stages. Although food taboos restrictions are rooted in cultural norms and traditional spiritual and religious beliefs, they are mainly related to unfavourable pregnancy outcomes and health problems post-partum, during lactation and among children and adolescents (Table 2). Hierarchical feeding practises means that guests or ritual leaders are fed preferentially. Men are seen as breadwinners, hence that control food purchases and distribution and eat first. There are future family or economic expectations attached to boy children. Consequently, boys may preferentially be fed and treated over girls, and reinforcing gender-based food discrimination. However, there are spiritual connections between the people, their food sources and the land and other ecological factors such as food taboos being linked to agricultural practises and production.

Therefore, cultural food security and cultural food sovereignty interventions couched with collectivism may lead to undocumented inequalities. Intra-household power dynamics, driven by hierarchically biased decision-making, obscure individual deprivation among subgroups, especially marginalised voices within the family setting that have limited say in how food is allocated(Reference Kakay3–Reference Amartya and Tinker5). Group conformity, the primary core of collectivism, affect individual food choices as it dictates what food is acceptable to eat, how it is prepared and who eats first. While this strengthens group identity, it also restricts access to food and suppresses dietary diversity and innovation(Reference Giffin99). Hence, group conformity and dependency on communal systems to promote social cohesion come at the cost of personal health or evolving nutritional needs. The effect on nutritional needs becomes profound when collectivist cultural values are enforced through customary practises and social norms not recognised or supported by formal policy structures.

In contrast, in individualist cultures food is tied to personal preferences, convenience and health objectives. Customised meals and eating alone are core behaviours. Food agency is governed by personal food choices that deviate from the collective. These choices may include personalisation (e.g., tailored meals in terms of own preferences, food types, preparation methods and portion sizes), dietary independence within a social contexts, convenience as a rationale that outweighs other considerations such as health or taste, slimming diets for aesthetics or physical appearance due to societal pressures about unrealistic beauty standards and self-advocacy for a vegetarian diets for ethical, environmental, or health reasons(Reference Tivadar and Luthar100).

Food security measures

Conventional food security has had adequate scales to depict levels of food insecurity, and these scales have been validated worldwide. Examples include the household food insecurity access scales, the food insecurity experience scale or the household dietary diversity score. However, the literature has been littered with a plethora of assessments, tools and indicators, with significant variability. By 1999, Hoddinott(Reference Hoddinott101) had identified more than 200 definitions and 450 indicators of food security, numbers that are more likely to have increased since then. Recently, Manikas and colleagues(Reference Manikas, Ali and Sundarakani102) undertook a systematic review of indicators measuring food security. They found that household-level adequacy of energy intake, and dietary diversity- and experience-based dimensions are the most frequently used food security indicators. They further found that food utilisation and stability dimensions are seldom captured when measuring food security. Nonetheless, the existing scales allow for comparison between groups within and between countries and across settings.

However, findings may not be generalisable due to many reasons. Existing food security scales assume universality in food needs. They heavily draw from individualistic values and do not account for informal food sharing networks and practises(Reference Manikas, Ali and Sundarakani102,Reference Jones, Ngure and Pelto103) . They use languages that have different meanings such as having enough food or running out of food, which are culturally relative. What constitutes ‘having enough food’ varies across cultures and is shaped by social norms, cultural identity and value belief systems, which in turn influence how individuals and communities perceive and respond to food scarcity. These scales can underestimate actual food security resilience and fail to detect hidden vulnerabilities when communal support erodes. In addition, the social desirability bias and cultural taboos may limit truthful reporting in structured food insecurity assessments, leading to systematic underreported.

Hence, existing scales do not measure the cultural relevance of food security (e.g., food sharing as an informal buffer against hunger) and the cultural contexts in which food security interventions are implemented(Reference Manikas, Ali and Sundarakani102,Reference Jones, Ngure and Pelto103) . They do not measure the loss of access to specific cultural or traditional foods and wrongly assume homogeneity of food needs by ignoring socio-cultural and spiritual roles of food and the lived realities of collectivist cultures. Communities may be found to be food secure despite profound cultural food insecurity. Similarly, decision-making in collectivist cultures is dynamic and collective, and goes beyond heads of households or individual caregivers to involve key community leaders such as elders, kin groups, or local leaders(Reference Singelis, Triandis and Bhawuk34,Reference Triandis86–Reference Hofstede88) . Existing food security scales assume a static decision-making making and count on the interviewee to provide answers that account for this complexity on behalf of the household(Reference Jones, Ngure and Pelto103). This can lead to a serious misrepresentation of how food is allocated or procured, due to obscure power dynamics and community-level negotiations. These gaps can lead to misinterpretation of food insecurity, blind spots and misaligned food security intervention interventions.

Tools to measure cultural food security (e.g., culturally appropriate food inventory or photovoice) and cultural food sovereignty (e.g., the adapted participatory rural appraisal or the adapted livelihood vulnerability index) are still in their infancy. They are yet to be psychometrically tested, and more efforts are needed to develop reliable, valid and stable scales to evaluate the impact of cultural food security and cultural food sovereignty interventions. Borrowing from existing scales to develop scales that can collect data on formal and informal food sharing networks and practises, intra-household experiences and hierarchy dynamics, integrate cultural food values and food value belief system would be a step in the right direction. It is only by reconciling measurement frameworks with local sociocultural contexts that we can design interventions that are both culturally relevant and effectively targeted

Conclusion

Whilst it is true that food security is a significant cultural issue as much as it is a public health challenge, conventional food security frameworks ignore cultural contexts in which they are implemented and evaluated. They fail to acknowledge the complex interplay of cultural feeding practises, gender-based food taboos and discrimination and hierarchy dynamics. These cultural dynamics govern intra-household food dynamics, gender roles and expectations and conditions shaping food choices and eating habits. By ignoring these cultural complexities, conventional food security approaches perpetuate inequities and inefficiencies and can lead to critical blind spots in data collection and misguide interventions. Therefore, a more nuanced understanding that embed cultural relevance, intra-group dynamics and collective autonomy is urgently needed to transform global food policies and practises and to bridge conceptual and operational gaps that introduce unjust and sustainable practises and differential nutritional outcomes. Nonetheless. a deeper, justice-oriented engagement with food systems reflective of lived realities, dignity, autonomy and cultural identity need to take precedence over nutritional and health objectives. These values must be incorporated into both policy and practise to truly transform global food systems.

Acknowledgements

This review was written whilst on an Academic Development Programme with Bridging Divides programme, Toronto Metropolitan University. During the revision, the authors acknowledge the use of ChatGPT-4o in addressing reviewers’ comments related to grammar, spelling and language clarity.

Author contributions

Conceptualisation: A.R, SC; Validation: A.R, Formal analysis: A.R; Resources: AR Data curation: AR, Writing(original draf)t: A.R; Editing and revision: AR; Visualisation: AR; Supervision: AR; Project administration: AR; Funding management: AR.

Financial support

None to declare.

Competing interests

None to declare.