Introduction

In the rudest stages of life, man depends upon spontaneous animal and vegetable growth for food …, and his consumption of such products consequently diminishes the numerical abundance of the species which serve his uses.

George Marsh (1864/Reference Marsh and Lowenthal1965:19)

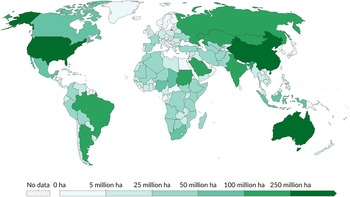

George Perkins Marsh’s (1864/Reference Marsh and Lowenthal1965) observations in Man and nature, made long before the AnthropoceneFootnote 1 was defined, provide early insights into the epoch many claim we live in today: marked by humanity’s unconstrained alteration of ecosystems on a planetary scale that has long-lasting and far-reaching consequences. The above passage in particular foreshadows humanity’s agriculture-based development which, as we now know, has led to a massive change in land use (i.e. soil degradation), biodiversity and habitat loss, water scarcity, greenhouse gas emissions (nitrous oxide and methane particularly), pollution, and climate change. These are core issues of the Anthropocene discourse, understood by Rickarts (Reference Rickarts2015:280) as ‘a grand tale about humanity and its place in the world told using a repertoire of tropes’. With food production being a leading driver of environmental change globally (Gibbs & Cappuccio Reference Gibbs and Francesco2022), scientific evidence strongly demonstrates that today’s agricultural practices account for nearly 30% of human-caused greenhouse gas emissions, around 70% of the world’s freshwater usage, and cover approximately 40% of the planet’s land area (i.e. croplands occupy 1.53 billion hectares or about 12% of Earth’s ice-free land; pastures occupy 3.38 billion hectares or about 26% of Earth’s ice-free landFootnote 2) (see Figure 1). Ironically enough, against this backdrop of extensive land use as well as global productivity gains,Footnote 3 inaccessible adequate food or chronic malnutrition continue to be a major issue in many parts of the world.Footnote 4 Studies indicate that to meet projected food requirements driven by population growth, shifts in dietary preferences (i.e. notably increased meat consumption), and growing bioenergy needs, food production would need to nearly double (Foley et al. Reference Foley, Ramankutty, Brauman, Cassidy, Gerber, Johnston, Mueller, O’Connell, Ray, West, Balzer, Bennett, Carpenter, Hill, Monfreda, Polasky, Rockström, Sheehan, Siebert, Tilman and Zaks2011).

Figure 1. World agricultural land use (source: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2024; published online at https://ourworldindata.org/land-use. The Creative Commons BY license).

The United Nations Climate Action initiative alerts that food ‘needs to be grown and processed, transported, distributed, prepared, consumed, and sometimes disposed of’, where each stage in this complex chain produces greenhouse gases that drive climate change.Footnote 5 As organic farming entails ‘crop and livestock production using natural sources of nutrients (such as compost, crop residues, and manure) and natural methods of crop and weed control, instead of using synthetic or inorganic agrochemicals’,Footnote 6 it is seen as a promising approach for reducing the environmental and ecologicalFootnote 7 impacts associated with sustainable development (Gamage, Gangahagedara, Gamage, Jayasinghe, Kodikara, Suraweera, & Merah Reference Gamage, Gangahagedara, Gamage, Jayasinghe, Kodikara, Suraweera and Merah2023). Of course, reality is much more complex. As Reganold, Glover, Andrews, & Hinman (Reference Reganold, Glover, Andrews and Hinman2001:926) write, ‘just because a system is organic or integrated does not ensure its sustainability’. A frequently cited Clark & Tilman’s (Reference Clark and Tilman2017) comparative analysis of organic and conventional agricultural systems showed that, in localized instances, the environmental impact of a conventional farm can actually be lower than that of an organic farm. Specifically, an organic agricultural system can prove better in terms of greenhouse gas emissions but higher in land use (Ritchie Reference Ritchie2017). And as Thomas (Reference Thomas2022) explains, expanding organic farming worldwide to maintain current food production levels would necessitate approximately an additional 10 mil km2 of farmland, ultimately decreasing rather than enhancing global biodiversity. Although the assessments of organic farming’s environmental impacts still vary widely in the scientific community (Debuschewitz & Sanders Reference Debuschewitz and Sanders2022), lower yield per acre compared to conventional farming is considered its key disadvantage. By contrast, in the coming fifty years, environmental stressors (i.e. rising temperatures, water scarcity, increasing soil and ocean acidification) will pose even greater challenges in meeting the food needs of a growing global population and an ever increasing appetite for meat (Fanzo, Hood, & Davis Reference Fanzo, Hood and Davis2020).

Following the tradition of semiotic landscape research (Jaworski & Thurlow Reference Jaworski and Thurlow2010) and Thurlow’s (Reference Thurlow2020) discourse-centred commodity chain analysis, the data for this article comes from three organic grocery store chains in Düsseldorf and Essen, Germany, producing beefy landscapes which complicate the pleas by scientists and health professionals alike to reduce red meat consumption—critical in addressing climate change. I analyse the semiotic material from organic food stores that promote beef as a benign part of food production methods aimed at resource preservation and minimizing environmental harm. By portraying cows as wholesome symbols of organic farming, highlighting the simplicity of beef preparation, and downplaying environmental consequences, these stores reinforce beef consumption and contribute to a broader ‘clean food’ narrative—one that obscures the unsustainable realities of industrial animal agriculture. The article thus aims to bring attention to (un)sustainability and climate change in general as topics that have been addressed in Language in Society only sparingly, particularly with regard to the systemic contributors to global warming that are so frequently overlooked. Serving as a demonstration-in-practice, the article integrates semiotic and supply-chain lenses complemented by (Social) Life Cycle Assessment criteria that refine the interpretation of semiotic landscapes where (selectively) excluded environmental impact information/sustainability profile are revealed.

The next section highlights some of the social, ethical, and labor inequalities embedded in organic farming and food systems, challenging their sustainability narrative. Before the analysis, I briefly describe Germany’s efforts to transform its agricultural systems by promoting organic farming and food culture which reflect a global trend of ethical consumption (Huddart Kennedy, Baumann, & Johnston Reference Huddart Kennedy, Baumann and Johnston2019) shaping people’s moral values, cultural capital, and social status.

Challenges of/in organic food landscapes

Social challenges associated with sustainable methods of organic farming have received limited academic attention. Probably the most obvious one concerns affordability and accessibility. Organic products typically come with higher price tags due to lower yields and generally labour-intensive practices. However, limited access to organic products, specifically in lower-income populations, can reinforce social inequalities and intensify food insecurity (see Aschemann-Witzel & Zielke Reference Aschemann-Witzel and Zielke2015; Hough & Contarini Reference Hough and Contarini2023). The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) acknowledges that organic farms often need more labour to replace conventional inputs like fertilizers and pesticides, while high-wage northern countries with shrinking rural populations often struggle to meet (manual) labour demands, typically addressed by employing migrant workers from developing and transitioning economies.Footnote 8 Thus, organic food landscapes capture the politics of agricultural labour, inviting a critical engagement with the following question as Alkon (Reference Alkon2013:665, 667) writes: ‘who is producing what kind of food, for whose benefit, and to whose disadvantage’ especially as ‘farm owners’ labour becomes constructed as socio-natural while migrant farmworkers remain invisible?’ (see farm workers with their backs turned in Figure 2).

Figure 2. Earthbound Farms, one of the US’s largest organic producers near Paicines, California (source: George Steinmetz for National Geographic, 2018. This image is reproduced under fair dealing/use for the purposes of scholarly comment and criticism).

More recently, in a Guardian article, Saša Uhlová (Reference Uhlová2024), a staff writer at the Czech online daily Deník Alarm, reports on her undercover experience as a migrant farm worker on an organic farm in Germany. Her story highlights the exploitative nature of behind-the-scenes migrant labour within Europe’s organic food supply chain, revealing low pay, long hours, physical pain, unstable schedules, and employers manipulating labour records to bypass regulations. In their qualitative study, Soto Mas, Handal, Rohrer, & Tomalá Viteri (Reference Soto Mas, Handal, Rohrer and Tomalá Viteri2017) investigate health and safety of organic farm workers in central New Mexico and report they may be at risk for respiratory diseases from environmental exposures, noise-induced hearing loss, skin disorders and cancer, heat-related illnesses, and mental health issues (i.e. high levels of stress, depression, suicidal thoughts)—just like conventional farmworkers.

This article does not aim to provide a rigorous definition of organic food landscapes, generally understood here as multimodal food environments which prioritize environmental sustainability.Footnote 9 But it is easily observable how they vary considerably in line with the stages of production, preparation, and distribution, and thus come in different shapes, styles, and sizes—from a field/farm to a store. Organic food landscapes introduce a full range of narratives, spatialities, materialities, actors, and agricultural commodities: fruits, vegetables, grains, mushrooms, and non-human animal (by)products. Organic livestock landscapes, in particular, realize distinct sites (not only because of the deleterious impact on environment) and affect the public discourse around topics like global warming, use of antibiotics, food safety, and moral principles. Yet, from an environmental ethics aspect, questions arise as to whether such farming practices can reflect the holistic and health-focused ideals of organic agriculture, which are fundamentally rooted in promoting sustainability, well-being, and preventing harm (Alrøe, Vaarst, & Kristensen Reference Alrøe, Vaarst and Kristensen2001). With regard to non-human animal well-being, scientific research on dairy cow behaviour suggests cows possess complex cognitive, emotional, and social traits (Marino & Allen Reference Marino and Allen2017). For instance, early cow-calf separation, which causes distress both for the calf and its mother (Johnsen, Ellingsen, Grøndahl, Bøe, Lidfors, & Mejdell Reference Johnsen, Ellingsen, Grøndahl, Bøe, Lidfors and Marie Mejdell2015), is practiced in organic dairy farming systems just as it is in conventional farming systems (Kälber & Barth Reference Kälber and Barth2014). Organically raised or not, non-human animals end up in places we hardly ever consider—farms and slaughterhouses where conventional, ‘humane’ killing methods are approved (see Kühl, Bayer, & Busch Reference Kühl, Bayer and Busch2022). With respect to human health, by contrast, studies on animal oncogenic viruses already confirmed an increased risk of developing various cancers in abattoir and meat processing workers (i.e. cancers of the buccal cavity and pharynx, lung, skin, pancreas, brain, cervix, lymphoid and monocytic leukemia, and tumors of the hemopoietic and lymphatic systems) (Johnson Reference Johnson2011) as well as in workers in the meat and delicatessen departments of supermarkets (Johnson, Cardarelli, Jadhav, Chedjieu, Faramawi, Fischbach, Ndetan, Wells, Patel, & Katyal Reference Johnson, Cardarelli, Jadhav, Chedjieu, Faramawi, Fischbach, Ndetan, Wells, Patel and Katyal2015). This is something that consumers with higher levels of education and income, as studies show (see O’Donovan & McCarthy Reference O’Donovan and McCarthy2002; Zepeda & Li Reference Zepeda and Jinghan2007; Baudry, Méjean, Péneau, Galan, Hercberg, Lairon, & Kesse-Guyot Reference Baudry, Méjean, Péneau, Galan, Hercberg, Lairon and Kesse-Guyot2015; Hansmann, Baur, & Binder Reference Hansmann, Baur and Claudia2020), do not necessarily think about while filling their shopping charts with ‘clean and sustainable’ products arguably of superior nutritional profileFootnote 10 (see Vigar, Myers, Oliver, Arellano, Robinson, & Leifert Reference Vigar, Myers, Oliver, Arellano, Robinson and Leifert2019; Thaise de Oliveira Faoro, Artuzo, Rossi Borges, Foguesatto, Dewes, & Talamini Reference Thaise, Dalzotto Artuzo, Augusto Rossi Borges, Rogério Foguesatto, Dewes and Talamini2024) and conveying a sense of prestige (Palma, Ness, & Anderson Reference Palma, Ness and Anderson2016). Organic food landscapes clearly project (dominant) food ideologies, labour politics, scientific inaccuracies, and signal distinction tendencies (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1984), supremacism, and the disconnection from more-than-human ‘nature’. These are all of great importance for language and semiotic studies, embedded in the systems which, as Kosatica & Smith (Reference Kosatica, Sean, Kosatica and Sean2025:6) write, ‘produce such extraordinary degrees of inequality [that] cannot be deconstructed without attention to the language and communication through which they are enabled’.

Sustainable agriculture and organic food consumers in Germany

The global food system is a major contributor to the Anthropocene, and without a rapid global transformation towards sustainable food systems, it will be impossible to meet the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) or the objectives outlined in the Paris Climate Agreement (Rockström, Edenhofer, Gaertner, & DeClerck Reference Rockström, Edenhofer, Gaertner and DeClerck2020). In Europe, The EU’s Food 2030 policy aims to foster sustainable food systems and closely aligns with organic farming by promoting eco-friendly practices, biodiversity, and soil health—core principles of organic agriculture. This initiative complements the EU’s Farm to Fork strategy, encouraging low-impact, resilient food production, and supporting organic farming as a pathway to address climate change, reduce pollution, and enhance food security.Footnote 11

A European country with a huge appetite for food system transformation is Germany (see Table 1). According to Germany Trade & Invest (GTAI), the economic development agency of the Federal Republic of Germany, the country is actively advancing its commitment to expanding organic agriculture, with a national target of converting 30% of farmland to organic practices by 2030.Footnote 12 To facilitate this transition, the state bank Landwirtschaft Rentenbank has introduced a four-year subsidy program, offering financial assistance of up to 40% for enterprises investing in organic farming systems. In 2023, one in seven farms in Germany was organic, totalling 36,680 farms or 14% of all farms across the country.Footnote 13 This shift is consistent with rising consumer interest in organic products within Germany, where the organic food market reached €16.08 billion in 2023. Consequently, Germany is the largest organic market in Europe. The demand for organic meat, in particular, grew by nearly 20%, contributing to an overall increase in organic food sales of €880 million, representing 7% of the total food market. The expansion of organic agriculture is further supported by Germany’s substantial agricultural machinery industry, valued at €7.5 billion in 2022, which provides essential equipment and innovation for the sector’s development.

Table 1. Germany’s organic farming transition: Key data and goals (source: Germany Trade & Invest (GTAI); see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7VAEu_oXt0o).

GTAI also quotes the former German Minister of Food and Agriculture, Cem Özdemir, who has emphasized the government’s unified commitment to establishing organic farming as the foundation of a sustainable agricultural and food system. Such progress of organic farming directly impacts the growth and diversity of markets for organic products (Michelsen, Hamm, Wynen, & Roth Reference Michelsen, Hamm, Wynen and Roth1999), especially organic supermarket chains such as Denns BioMarkt, Bio Company, and Alnatura—the three biggest in Germany.Footnote 14 Besides selling certified organic fresh and pre-packaged food, household cleaning and toiletry items, and basic clothing and accessories items (usually for babies and kids), one thing such stores have in common is a preference for regional products that strengthens the local food supply (especially fruit, vegetables, dairy products, and meat).

Recent studies indicate that people in Germany are motivated to buy organic food due to strong attitudes toward sustainability and environmental protection, aligning with climate-conscious values (Joseph & Friedrich Reference Joseph and Friedrich2023). Although previous research suggests that organically grown food may carry a higher risk of contamination from pathogens like E. coli and Salmonella due to the more frequent use of manure (e.g. Sheng, Shen, Benedict, Su, Tsai, Schacht, Kruger, Drennan, & Zhu Reference Sheng, Shen, Benedict, Yuan, Tsai, Schacht, Kruger, Drennan and Zhu2019), German consumers frequently associate organic products with health and safety, ‘untreated’, fresh, and sourced from better animal husbandry practices, which enhance perceptions of quality, taste, and waste reduction (Brümmer & Zander Reference Brümmer and Zander2020). Concerns about the environmental impacts of food transport and trust in well-regulated local standards have also been reported to strengthen the preference for buying organic food produced in Germany (Pedersen, Aschemann-Witzel, & Thøgersen Reference Pedersen, Aschemann-Witzel and Thøgersen2018). Nonetheless, intensifying organic food consumption raises an ethical-environmental dilemma regarding non-human animal products, particularly (red) meat. On one hand, food-animals’ agency is rarely considered (Bovenkerk & Keulartz Reference Bovenkerk and Keulartz2021). On the other hand, as Fairlie (Reference Fairlie2010) argues, consuming small amounts of carefully selected meat might be more sustainable than complete abstention, since certain resources (e.g. types of grasslands and waste materials) are optimally utilized through animal rearing. It is important to note, however, that contemporary global meat production largely relies on feeding livestock with agricultural resources that are also suitable for direct human consumption or are grown in agricultural fields which could be used to produce food edible to humans, rather than utilizing non-edible resources such as grasslands or waste materials.Footnote 15

The material and non-human turn

In recent years, research on good/pure/clean/local food discourse, usually associated with sustainable production, has modestly grown, specifically around themes like authenticity, green consumerism, and ethical branding. In their studies, language and communication scholars seek to demonstrate how certain food products are represented and point to the broader social narratives and ideological influences embedded in the food discourse. Eriksson & Machin’s (Reference Eriksson and Machin2020) special issue of Discourse, Context and Media on ‘Discourses of ‘good food’: The commercialization of healthy and ethical eating’ bring eight discourse-focused papers together highlighting multimodal arrangements found in everyday food-related communication. These studies show how food discourse blends notions of health, morality, nationalism, and neoliberal values, positioning food not only as a dietary choice but a statement of identity, ethics, and cultural values. While there is no doubt that scholars in discourse studies look at the ideological and communicative dimensions of food-related practices and criticize texts that often shift focus away from mitigation measures (see Schraedley & Compton Reference Schraedley, Compton and Boerboom2015; Ledin & Machin Reference Ledin, Machin, Pauwels and Mannay2020), the existing work in general lacks scientific perspectives from natural sciences which would rigorously situate food discourse within (capitalist-driven) unsustainable food systems (e.g. by evaluating the scientific validity of organic food claims, reading the semiotic landscape through quantitative scientific insights). The article by Cook, Pieri, & Robbins (Reference Cook, Pieri and Peter2004) possibly stands out as a rare example interrogating how scientific discourse is employed in debates about genetically modified food that, just like organic food, operates within the same global capitalist structures prioritizing branding, differentiation, and profit. While their study does not engage with scientific discourse or methodologies, Mapes & Ross (Reference Mapes and Andrew2022) examine chefs’ Instagram posts and identify practices and strategies (meat-focused eating and, worth noting, merged locality/sustainability as a rhetorical strategy) to show how these are entangled with class, privilege, and status. And although their study demonstrates that performative sustainability frequently works as an elite discourse and a way of claiming distinction, Mapes & Ross themselves emphasize (Reference Mapes and Andrew2022:260), ‘this is not an article about climate change per se’. Thus, as things stand, the current work on food discourse does not seem to offer a comprehensive schema for analysing food systems of the Anthropocene, texts about problematic food production practices (e.g. working-class labouring bodies as in Thurlow (Reference Thurlow2024), multispecies interdependencies, the depletion of natural resources, biodiversity erasure), or how food discourse aligns with material climate change impacts (or not). Therefore, I deliberately build upon the insights of limited work in the field that takes a critical approach to investigating anthropocenic landscapes and practices, specifically human-farm and human-animal relations.

Here I single out more recent contributions which distinctly problematize human-made issues symptomatic of larger challenges of the Anthropocene, push environmental discussion in the field, and fasten the non-material and material. Gavin Lamb (Reference Lamb2020, Reference Lamb2021, Reference Lamb2024) offers a series of studies on the interaction between humans and nonhuman wildlife within ecotourism and conservation contexts, specifically focusing on sea turtles and monk seals in Hawai‘i. His work promotes the more-than-human turn in discourse studies by integrating ecological perspectives and shifting focus beyond human-centred analysis to examine how discourse affects multispecies relations and public spaces. By exploring the ideologies that exclude animal languages from the focus of linguistic research and how dairy cows draw on various resources to communicate, Leonie Cornips’ (Reference Cornips2022) work disrupts the hierarchical power structures that privilege humans over animals based on their linguistic agency and superiority. Her approach emphasizes a relational, dynamic agency that emerges from the interconnected roles of humans, animals, and other factors (Cornips Reference Cornips2024). By foregrounding the presence of animals in semiotic landscapes, within and beyond the confines of agricultural settings, both authors address ethical concerns and indirectly expose what remains pertinent to the evolving global food landscapes. Ultimately, their theoretical interventions influence sociolinguistic perspectives on human (consumption) behaviors underscoring the necessity of transformation in response to the emergent realities of the Anthropocene and such insights advocate for semiotic landscape research to align with ecological principles, emphasizing the interconnectedness of all forms of life.

Thurlow’s recent interventions provide theoretical dimensions and analytical directions for engaging with various sites along global commodity chains. By raising sociolinguistic interest in waste, Thurlow (Reference Thurlow2020) considers humanity’s (environmental) impact and transformation of landscapes through practices of consumption and disposal, and highlights the sociopolitical consequences of the processes of valuation/devaluation where waste generates a significant material testament to the Anthropocene’s environmental legacy. He proposes a discourse-centred commodity chain analysis and expands sociolinguistic inquiry into under-explored contexts in order to ‘defetishize a single text or practice’ (Thurlow Reference Thurlow2024:12). In ‘Rubbish? Envisioning a sociolinguistics of waste’, Thurlow (Reference Thurlow2022:391) calls for a discursive re-construction of waste and the investigation of two crucial social relations—the lives of those who ‘live and work with/in waste’ and the social relation between waste producers and those who ‘manage’ it. In ‘Working beside/s words’ (2024:9), Thurlow exposes ‘demanding, exhausting and relentless’ non-verbal, embodied labor of farmworkers on an ‘antisocial’ tomato field in Extremadura, Spain. While not explicitly environmental in nature, Thurlow’s work ties into the issues of labor-intensive farming and some of the environmental implications of large-scale food production. After all, the invisibility of both waste and labor resonates with the generally unnoticeable environmental degradation in food systems.

The work of these scholars gives more attention to semiotic and non-material dimensions of human practices, integrates environmental, multispecies, and relational perspectives, and thus contributes to a deeper understanding of how language and discourse both reflect and shape the landscapes of Anthropocene. Along those lines, this article acknowledges a post-humanist framework—decentring human exceptionalism and centring the animal and non-human entities (Cornips, Deumert, & Pennycook Reference Pennycook2024) and responds to Pennycook’s (Reference Pennycook2024:17) call for an investigation ‘of the relationship between language and everything else’. Specifically, it broadly puts forward everything else as the biosphere entailing all life on Earth and interactions within ecosystems.

Data and method

Following the tradition of semiotic landscape research investigating how ‘written discourse interacts with other discursive modalities: visual images, nonverbal communication, architecture and the built environment’ (Jaworski & Thurlow Reference Jaworski and Thurlow2010:2), data for this study consist of photographs taken in/around (i.e. facades, parking lots) three organic food store chains (two Denn’s BioMarkt stores, two SuperBioMarkt stores, one Alnatura store) in Düsseldorf and Essen, Germany. Founded in 2003 in Geretsried (Bavaria), Denn’s BioMarkt is the largest organic supermarket chain (by store count) in the country, operating 340 stores across Germany and Austria; SuperBioMarkt, established in 1973, is headquartered in Münster and operates twenty-six stores primarily within North Rhine-Westphalia; established in 1984, Alnatura is headquartered in Darmstadt (Hesse) and operates 154 stores across Germany, with the highest concentration in Baden-Württemberg.

Data was collected during a two-week fieldwork in Düsseldorf and Essen in February 2023. My PhD assistant and I visited organic food stores based on their prominence within the local commercial landscape. These stores belong to the largest and most recognizable organic food store chains in the region. Selecting the most established stores ensures that captured semiotic practices are likely to be significant in shaping consumer behaviour. We visited each store once, posing as regular customers and photographically documenting semiotic data. Taking photographs was not prohibited in the premises and a single visit was sufficient for capturing the stores’ relatively stable arrangements. However, given that ephemeral materials such as promotional posters or brochures are subject to frequent updates, primary data are supplemented by the website content to capture a range of representational practices which situate beef within organic retail environments in Germany. Supplementary data were helpful in confirming the consistency of observed signs in three different chains, and while the stores display identical/similar content (e.g. digital messages turned into printed posters), these are temporary indoor signs and may not be present during fieldwork. Furthermore, websites serve not only as commercial but carefully curated platforms promoting a store’s brand identity. In particular, the ‘About us’, ‘mission statement’ and similar online sections explicitly show a store’s business mantra and self-representation.

To expose some of the socio-environmental ‘costs’ behind beef production and retail, I draw on Thurlow’s (Reference Thurlow2020) discourse-centred commodity chain analysis, which traces how a discourse or a single text/semiotic practice is produced, circulated, and recontextualized across various settings and by different social actors. This framework seems to align with (Social) Life Cycle Assessment applied in environmental sciences and industrial ecology—methodological frameworks assessing the environmental and social impacts ‘of products and services across their life cycle (e.g. from extraction of raw material to the end-of-life phase, e.g. disposal)’ (United Nations Environment Programme Reference Norris, Traverso, Neugebauer, Ekener, Schaubroeck, Garrido, Berger, Valdivia and Lehmann2020:2). Despite their methodological and disciplinary differences, both frameworks contribute to uncovering underlying processes and impacts within diverse production systems and advocate for transparency. Finally, I draw on Gibson’s (Reference Gibson, Robert and Bransford1977) concept of affordances which provides a valuable framework for examining how consumers perceive beef as a sustainable product. Gibson (Reference Gibson1979:127) defines the affordances (of the environment) as ‘what it offers the animal, what it provides or furnishes, either for good or ill’. This concept can be applied to explore how consumers interpret a beef steak, for example, and the motivations it creates for purchasing. In this context, affordances can be understood as semiotic features that push us to consume something.

Enregistering the cow

Sociodemographic studies on food consumption behaviour exploring disparities in access to organic food typically give insights into correlation with more affluent urban neighbourhoods (e.g. Vittersø & Tangeland Reference Vittersø and Tangeland2015; Li, Ghiasi, Li, & Chi Reference Li, Ghiasi, Xiaopeng and Chi2018; Garcia, Garcia-Sierra, & Domene Reference Garcia, Garcia-Sierra and Domene2020). In Düsseldorf, access to organic food stores appears to be relatively equitable, as these stores are situated in central, high-traffic areas. In contrast, the distribution of such stores is clearly influenced by socioeconomic/ethnic divides in Essen—something Kosatica (Reference Kosatica2024) documented in her investigation of the city’s ‘green’ semiotic material and politics which reinforce the familiar divide between the North and the South of the A40 highway. In line with Alkon’s (Reference Alkon2013:679) observation, organic food stores hold ‘widespread appeal, particularly among the predominantly affluent, white subjects who are generally hailed by the romantic discourses surrounding local and organic food’. Visited stores do not demonstrate efficiency regarding facades, roofing, and parking configurations. There is an absence of visible indicators of sustainable practices, such as insulated facades, green roofing (which is not observable), solar panels, and so on. Storefront or primary signs, typically positioned above the entrance, have been recognized as an important multimodal text that actively contributes to meaning-making within semiotic landscapes (e.g. Gendelman & Aiello Reference Gendelman and Aiello2010; Kosatica Reference Kosatica, Blackwood and Macalister2019; Androutsopoulos & Chowchong Reference Androutsopoulos and Chowchong2021). Organic store logos predominantly feature light green and prominent red—a set of complementary hues (van Leeuwen Reference van Leeuwen, Böck and Pachler2013)—on facades usually unadorned and constructed from glass or wood-like materials and messages, such as gesund ‘healthy’, lecker ‘tasty’, saisonal ‘seasonal’, ökologisch ‘ecologic’, transparent, regional, and frisch ‘fresh’. The interior’s simple content is aligned with the exterior design—rustic materials, wooden shelves, woven baskets, canvas bags, receipt paper free of polycarbonate plastics, fruits and vegetables unwrapped adding to a ‘fresh’, ‘untreated’ visual appeal. In-store signage that stands out emphasizes locality with messages that construct authenticity and rural places (German farms), associating organic products with ‘the agrarian ideals of small-scale food production, community engagement, and ecological responsibility’ (Johnston, Biro, & MacKendrick Reference Johnston, Biro and MacKendrick2009:510; see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Displays of regional meat, vegetables, and fruits suppliers.

A particular store section drawing attention is the meat department which has not been extensively studied in general, but is widely regarded as a crucial image-building element in food stores (Smith & Burns Reference Smith and Burns1997) due to human cultural attachment to meat that goes beyond nutrition (Barthes Reference Barthes and Lavers1972). Organic food stores generally provide self-service meat sections featuring large refrigerators stocked with pre-packaged meat products (Denn’s BioMarkt and Alnatura), while full-service meat counters are less common (SuperBioMarkt) (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Meat refrigerators.

Meat sections are meaning-making resources and sites of critical pedagogies, prompting us to interrogate the micropolitics embedded within so-called sustainable consumption practices. They reveal the paradox in which places that claim to offer sustainable alternatives actually push meat into human diets, thus actively contributing to the broader process of meatification Footnote 16 (Weis Reference Weis2015). My focus in this article is specifically on beef—not to single out a convenient example, but because beef holds the highest climate impact among all protein sources (Vitali, Grossi, Martino, Bernabucci, Nardone, & Lacetera Reference Vitali, Grossi, Martino, Bernabucci, Nardone and Lacetera2018), starkly contradicting the prominent sustainability narratives promoted by organic stores. To clarify, organic stores do advocate for organic farming as inherently sustainable, irrespective of the final consumable product, encouraging customers to view any purchase as a meaningful contribution to environmental and climate protection.

(1) We are certain that only organic farming has a future—a future without synthetic fertilizers and chemical pesticides. That’s why we are committed to this cause. By choosing to shop with us, you help ensure that many hectares of land are converted to organic farming each year, permanently free from synthetic plant protection products. This benefits animals, the environment, and people alike, securing a future for the biodiversity of cultivated landscapes. This means that as a customer, you make an important contribution to protecting what is essential for survival: climate, environment, fellow creatures, resources, and diversity, regardless of what you purchase from us. (Source: https://www.biomarkt.de/bio-wissen/aktuelles/warum-bio-kein-luxus-ist)

This rhetorical move subtly reinforces a perception of universal sustainability and purposefully overlooks environmental implications associated with organic beef production. Namely, the greenhouse gas emissions associated with organic beef production amount to 24.62 kg CO₂ equivalents per kilogram of live weight, compared to 18.21 kg CO₂ equivalents per kilogram for conventionally raised beef (Burrati, Fantozzi, Barbanera, Lascaro, Chiorri, & Cecchini Reference Buratti, Fantozzi, Barbanera, Lascaro, Chiorri and Cecchini2017). ‘Happy cows’, as stores like to call them, that become beef emit even more methane as they digest food and produce manure as well. Rising beef production requires increasing quantities of land. New pastureland is often created by cutting down trees, which releases carbon dioxide stored in forests. Thus, organic food stores indeed push me to focus on beef, as it is in these places that cows are centralized within the organic agriculture and, by extension, sustainability discourse. Cows appear just about everywhere—product packaging, in-store advertisements, outdoor signage, websites—reinforcing the perception of organic beef as unquestionably sustainable and legitimizing its place within an environmentally conscious consumer landscapel (see Figures 5 and 6).

Figure 5. In-store signs.

Figure 6. Official website content (source: https://www.biomarkt.de/tierwohl; https://www.alnatura.de/de-de/magazin/warenkunde/warenkunde-rindfleisch/).

Of course, it is possible that the cow repeatedly resurfaces since cows are raised and killed for many products—milk, cheese, meat—unlike pigs, for example. However, similar to how landmarks like the HOLLYWOOD sign are ‘global linguistic-semiotic registers’, as Smith, Järlehed, & Jaworski (Reference Smith, Järlehed and Jaworski2025) demonstrate, it appears that the cow in organic food stores and digital spaces also operates as an enregistered emblem (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Järlehed and Jaworski2025 after Agha Reference Agha2006). The value of organic beef is circulated through the peculiar and regular reproduction and circulation of the cow. Besides its role in political economy producing the Anthropocene, the cow also pushes us to think about the meaning of food stores because it is quite a powerful trail of exploitative structures and climate impact in general. In fact, it seems that the organic food store is a cleaning station where ‘messy histories’ of a product are removed from view. To be sure, when the cow is paired with sustainability (the word itself), the effect seems to be guaranteed. Indeed, sustainability is a special commodified linguistic resource (Cameron Reference Cameron2000; Kosatica & Smith Reference Kosatica, Sean, Kosatica and Sean2025), a reassuring token adding special value to all kinds of things and services. This match made in heaven accomplishes what Irvine & Gal (Reference Irvine, Gal and Paul2000) identify as erasure, transforming the not-so-simple mechanisms (in ecological sense) into simplified green narratives which, in this case, recontextualize organic beef as nothing but a climate-conscious choice.

Sanitizing beef

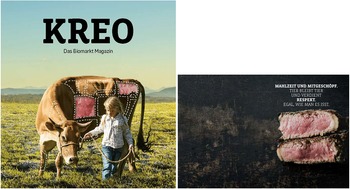

Direct invitations to consume beef, along with visual presentations of portion servings, are particularly prominent in recipes commonly featured on websites and in magazines sold in the stores (see Figure 7).

Figure 7. Cover and the first page of the KREO magazine, Denn’s BioMarkt (source: https://kreo.biomarkt.de/tier/page/1).

‘Meal or a fellow creature.

An animal remains an animal and deserves respect.

No matter how you eat it.’

(2) Hearty enjoyment

In organic cattle farming, regular grazing in the fresh air is essential, also to enable the cattle to display their distinctive social behavior.

Beef is a red meat and impresses with its high iron content and offers different textures depending on the piece. Whether juicy entrecôte, tender minced meat or spicy sirloin steak - we have the right beef for you for every occasion and every season! (Source: https://www.biomarkt-bestellung.de/collections/bio-rindfleisch)

Such texts present quite a perplexing association between meat and the animal itself, consistently emplaced within a natural landscape. This discursive move serves to obscure the realities of the production process, casting it in a more enigmatic manner. Most often, backgrounds are decontextualized to the point where we only see a pastoral scene, simply assuming a German field or a farm—a semiotic choice fostering a connection to rural heritage within the urban context of modern consumerism. As Alkon (Reference Alkon2013) notes, animals and the farms in which they are raised are portrayed as simultaneously ‘natural and as the product of human labor’. When cows are depicted with others, they are typically shown alongside the ‘real’ producers—farmers or (their) children—emphasizing a human presence and reinforcing an idyllic vision of agriculture. Johnston and colleagues (Reference Johnston, Biro and MacKendrick2009) identify a recurring theme of brands invoking specific rural landscapes and/or associating themselves symbolically with an idealized agrarian lifestyle. This framing helps construct an ‘authentic’ image of beef production, often highlighting verified organic practices or local sourcing while concealing the extensive, ethically complex production chains behind beef. Such idealized imagery extends to scenes of children interacting with cows—an appeal to innocence (Faulkner Reference Faulkner2011) or a visual tactic used to deflect the viewer from the uncomfortable ethical realities of meat production, especially slaughter (Cairns & Johnston Reference Cairns and Johnston2018). This is also what extract (2) points to so clearly. First, cows regularly grazing in the fresh air and displaying their distinctive social behaviour does not result in a more sustainable option—quite the opposite. Second, the quick shift from a living cow to consumable beef glosses over two environmentally and ethically critical phases: the suffering of ecosystems and animals themselves, or in other words, the ecological impacts of meat production and the act of slaughter itself. Diverse linguistic ‘distance mechanisms’ employed in the context of cattle representation in the meat industry discourse have been already observed (Stibbe Reference Stibbe2001). However, it seems that this discursive move emphasizing quick preparation over deeper environmental considerations is what, according to Matwick & Matwick (Reference Matwick and Matwick2019:544 after Gilmore & Pine Reference Gilmore and Pine II2007), influential authenticity is about: ‘part of the farm-to-table movement is the discourse of one’s food choices having a larger consequence globally in terms of sustainability and the environment’. And as Adams (Reference Adams1990:96) writes, ‘by speaking of meat rather than slaughtered, butchered, bleeding … cows and calves’, we engage in a language that sanitizes reality. In simple words, by purchasing beef carrying the label organic/bio, shoppers participate in unsustainable practices under the illusion of ethical consumption.

Of course, consumers do not merely approach meat as a source of nutrition; rather, purchasing meat, as any other food, reflects their relationship with themselves, and in the context of grocery shopping, convenience is often key (Verlegh & Candel Reference Verlegh and Candel1999). A notable example here is the imported Angus beef steak—tender, muscular, particularly juicy, and marketed with a 20% discount (see Figure 8). While it is not locally sourced, it is packed and certified organic in German; endorsed by French euphemisms suggesting premium quality of a boneless cut from the rib area. Matwick & Matwick (Reference Matwick and Matwick2019:539) illustrate that authenticity is inherently associated with organic food products: ‘the product cannot be replicated anywhere else by anyone else, giving it an elusive quality’. In their LL study of a Japanese supermarket in Singapore, they observe how authenticity is also signified through foreign terms, following Jurafsky, Chahuneau, Routledge, & Smith (Reference Jurafsky, Chahuneau, Routledge and Smith2016:19), who argue that ‘French, an already established language in gastronomy, is … a high-status culinary language’.

Figure 8. Angus beef steak.

This beef steak does not come from an exclusively grass-fed cow, although its packaging conjures idyllic pasture imagery, with cardboard elements depicting a lush Irish landscape. The packaging meets some criteria of circular economy principles, as the cardboard tray is fully (100%) recyclable, yet it lacks detail about thermoplastics and elastomer plastics like the PLA label, a common biodegradable alternative to fossil-based PET. Despite this, the packaging remains easily disposable, which somewhat complicates the values of meat reduction, a topic rarely addressed in organic food stores. In Germany, the cardboard component is disposed of in paper bins, while the plastic wrap goes into yellow bags (gelber Sack). There are suggestions that steaks are then to be prepared by drizzling oil into a hot pan, seasoning generously with salt on both sides and a five-minute steak dinner is ready; no vegetable side needed. This is a kind of text available on posters, websites, or in magazines of organic food stores, encapsulating the demand for convenient, everyday organic meals, which, as Sundet and colleagues (Reference Sundet, Hansen and Wethal2023) argue, drive consumers toward effortless food preparation and consumption.

On the packaging’s Nutrition Facts Label (Figure 9), a detailed breakdown of macronutrients, such as essential vitamins, minerals, or amino acid profiles, is not visible. While this steak contains around 100 mg of omega-3 fatty acids, for someone who wants the best balance of omega-3 to omega-6 ratios, it would be useful to read somewhere in the store that the same portion of salmon—with a far lower carbon footprint—contains 5000 mg. This is why Lynch & Giles (Reference Lynch and Giles2013) warn about texts that imply that the so-called sustainable food consumers are merely passive recipients lacking full agency in determining their dietary needs. Thus, besides convenient preparation, organic beef affords a quick, costly, and an unsustainable meal (apart from its packaging recycled through the German waste management system).

Figure 9. Agnus beef steak packaging.

Although organic products are often associated with traceability, local production, small-scale sourcing, and transparent information from producer to consumer, organic markets in some parts of Europe are often ‘highly processed, often imported, and consumer access to information about producers is frequently limited’ (Wier, O’Doherty Jensen, Mørch Andersen, & Millock Reference Wier, O’Doherty Jensen, Mørch Andersen and Millock2008 on Denmark and the UK). Similarly, in German organic stores, certain discursive spaces or sites in Thurlow’s (Reference Thurlow2020:362) terminology, are simply omitted and ‘the origins or sources … come to be obscured, forgotten, or erased altogether’. But, by connecting (Social) Life Cycle Assessment criteria for energy-related impact categories to discourse-centred commodity chain analysis, we can seek to restore the missing links as we consider how a product’s CO2 footprint is calculated in the production system. In other words, we can think about texts on impact categories such as land use, water use, biodiversity, toxicity, and particulate matter. From a socio-ethical perspective, we might look for texts regarding animal feed production, storage practices, transportation methods, nutritional content, and manure and waste management. Some of these aspects are in fact visually represented or conveyed. Yet, the aesthetic and textual associations of beautiful landscapes and delicious meals obscure the real environmental costs of agricultural products like beef.

The omission of information on land and water usage, biodiversity, and particulate matter is starkly evident, constructing a narrative that distances beef from its ecological impact. By presenting beef attractively packaged in big refrigerators in high-end organic stores, and avoiding less appealing production aspects, organic stores contribute to a ‘clean food’ narrative that masks unsustainable realities. Organic beef, in the words of Soinski (Reference Soinski2021:43), remains ‘a powerful signifier’ where the omission of inconvenient texts sustains the unspoiled ‘meanings that have become so important to … people’. Rather than a simple absence, it appears that omission serves as a semiotic strategy which draws power from the allure of the organic and the pristine (Smith Reference Smith2024), thus suppressing the reality of planetary crisis and fostering an ethical consumer experience. In this sense, it could be argued that omission represents a concealment of the Anthropocene where we find a sanitization of supply chain externalities. It is no surprise that in the modern age of (media) obsession with cleaning and decluttering, food stores as carefully organized microclimates aim to purify the commodity’s true ecological footprint as we push all that is uncomfortable into the idealized world of cleanliness, control, and aesthetics, and ‘pursue personal purity while ignoring the greater social problematic’ (Anfinson Reference Anfinson2017:220).

Concluding remarks

This article has sought to demonstrate that organic food stores, while often associated with sustainable food consumption, are paradoxically meat-intensive places. Such observation has significant implications for critically understanding what Sundet and colleagues (Reference Sundet, Hansen and Wethal2023) describe as meaty routines and the broader challenges of unsustainable consumption. Despite global awareness of the adverse impacts of meat consumption on health, animal welfare, and the environment, the article contends that organic food stores in Germany perpetuate high levels of meat consumption and openly legitimize livestock production and consumption, while neglecting the environmental consequences tied to meat production. The analysis has shown how beef, in particular, is semiotically positioned within organic food stores as both a natural and healthy element of a nutritious diet. By emphasizing natural authenticity (Gilmore & Pine Reference Gilmore and Pine II2007) over sustainability, organic food stores avoid confronting the ecological implications of their practices. The semiotic focus on concepts like local production, naturalness (Verhoog, Matze, Van Bueren, & Baars Reference Verhoog, Matze, Van Bueren and Baars2003) and ethically acceptable treatment before slaughter, obscures the significant environmental costs of livestock farming. These narratives set aside broader ecological principles, including reduced meat consumption and more sustainable dietary practices. Following Carol Adams’s (Reference Adams1990) concept of the absent referent, the article contends that while cows are semiotically present in organic food landscapes, their slaughter and the environmental impacts of beef production remain conspicuously absent. The meanings of sustainability constructed in these spaces depend on this absence, revealing how easily claims of sustainability can be made through incomplete and selective narratives.

The development of the organic meat sector and its probable low total sales due to high pricing (Dmitri & Oberholtzer Reference Dimitri and Oberholtzer2009) indicates that it is not too late for scholars to offer direct semiotic interventions that critically engage with the representation of organic (red) meat and its environmental implications, especially considering a wider gap on the role of meat production in climate change in contemporary discourse.Footnote 17 As organic food has moved into mainstream markets (Pinard, Byker, Serrano, & Harmon Reference Pinard, Byker, Serrano and Harmon2014) the conventionalization of organic food (Constance, Choi, & Lara Reference Constance, Choi, Lara, Freyer and Bingen2015) has amplified the importance of identifying such texts that are generally in the hands of non-experts, constructed through deliberate semiotic strategies which do more work than the written scientific language and create specific meanings in different micro-landscapes (Juffermans Reference Juffermans, Peck, Stroud and Williams2019) (i.e. the meanings of sustainability in organic food stores vs in scientific realms). The semiotic landscape research is thus uniquely positioned to trace anthropocenic practices semiotically embedded in everyday life and to address the ‘unseens of the Anthropocene’ in Lowe’s (Reference Lowe, Howe and Pandian2020) words. And by engaging comprehensively with scientific literature, it becomes a useful component of a wider interdisciplinary toolkit that can contextualize measured data and add social meaning to non-intuitive environmental statistics.

Acknowledgements

This article is based on a presentation made at the 14th Linguistic Landscape Workshop (Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Centro de Investigación MIRCo; 6–8 September 2023), as a part of the colloquium ‘Anthropocenic landscapes: The semiotics of a dystopian future’. I am thankful to the organizer of this colloquium, Sean. P. Smith, for his constructive comments and careful attention throughout the editorial process. I would also like to thank Laura Imhoff for her fieldwork assistance. I am deeply thankful to my husband whose grounding in environmental thought has inspired many aspects of this article. I acknowledge the use of OpenAI’s ChatGPT for locating policy and regulatory documents, primary sources, as well as factual and statistical checks on organic food production and consumption. All errors remain my own.