Introduction

A parent and young child are in the cereal aisle of the grocery store. The little girl is wailing while pulling on her mother’s jacket, begging for Lucky Charms. Remembering the recent book that she read about positive behavior management, the mother pretends to be busy rereading the shopping list in an attempt to actively ignore the tantrum.

The little girl’s emotions – intense anger at being reminded that she is allowed to choose only one treat and she already chose cookies – are on full display for everyone in the store. Less obvious, though, are the intense emotions coursing through the mother. The mother appears calm and neutral, not because that is how she feels, but because she is downregulating waves of negative emotions: anger at her daughter’s noncompliance (which leads to the urge to yell); frustration at herself for bringing her daughter to the store when she knew she did not have a good nap (which leads to negative self-talk), embarrassment about what other shoppers might be thinking about her, and anxiety because now that this is taking so long, they are going to hit rush hour traffic on the way home (both of which almost make her give in to her daughter in order to make the crying stop).

Despite experiencing all of these feelings, the mother downregulates them because in that moment she knows that acting on them would ultimately not support her goal: to move on from the cereal aisle as soon as possible without the Lucky Charms, and without escalating her daughter’s behavior.

When her daughter’s cry fades to a whimper and she starts to slowly walk away from the Lucky Charms, the first feeling that washes over the mother is relief. Instead of simply basking in the relief, though, she summons up feelings of pride in order to praise her daughter for calming down and following the rules and compassion to provide validation for her daughter’s disappointment.

Had the mother struggled to downregulate her feelings of anger, frustration, and anxiety, she may have acted on her urges: yelled “Fine! Fine! You can have the Lucky Charms too. Just be quiet already!” and yanked on her daughter’s arm to get her out of the store quickly. The mother would leave feeling defeated and telling herself she is a bad mother. The daughter would feel scared of her mother’s outburst and sore from her arm having been pulled. And the entire scenario would be more likely to happen again as the daughter’s tantrum behavior was reinforced.

The conceptualization of parenting as a process that is “affectively organized” came about in the early 1990s, with the publication of Theodore Dix’s seminal paper on the topic. Dix (Reference Dix1991) delineated how emotions and parenting are intertwined, focusing on how parenting activates emotions, how the specific emotions experienced by parents engage them in interaction with their children in particular ways, and how parents’ emotions are then regulated. In the 30 years since the publication of that paper, many studies have documented the wide range of emotions elicited by parenting (Bradley et al., Reference Bradley, Hurwitz, Harvey, Hodgson and Perugini2013; Hajal et al., Reference Hajal, Teti, Cole and Ram2019), and meta-analyses have shown that the emotions parents experience during parent–child interaction have an impact on how they behave in those interactions (Rueger et al., Reference Rueger, Katz, Risser and Lovejoy2011). However, although parents’ emotions influence behavior, they do not necessarily determine it (Hajal & Paley, Reference Hajal and Paley2020), as parents may – and often do – regulate their emotions. The notion that parents’ emotion regulation and dysregulation contribute to their parenting behaviors is now widely accepted, with enough studies conducted to support several reviews and even a recent meta-analysis (Havighurst & Kehoe, Reference Havighurst, Kehoe, Deater-Deckard and Panneton2017; Zimmer-Gembeck et al., Reference Zimmer-Gembeck, Rudolph, Kerin and Bohadana-Brown2022). Furthermore, intervention programs focused on preventing or reducing child mental health symptoms are increasingly incorporating components to enhance parents’ emotional regulation (Havighurst et al., Reference Havighurst, Murphy and Kehoe2021; Luby et al., Reference Luby, Barch, Whalen, Tillman and Freedland2018; Mogil et al., Reference Mogil, Hajal, Aralis, Paley, Milburn, Barrera, Kiff, Beardslee and Lester2022; Sanders et al., Reference Sanders, Bor and Morawska2007). Yet, there is still much to be understood about the nature of parental emotion regulation and the manner in which it supports (or undermines) parenting that leads to healthy outcomes for children. This chapter reviews advances in our understanding of associations between parental emotion regulation and parenting behavior over the past 30 years, as well as suggesting avenues for future research.

3.1 Key Concepts: Emotion Regulation and Parenting

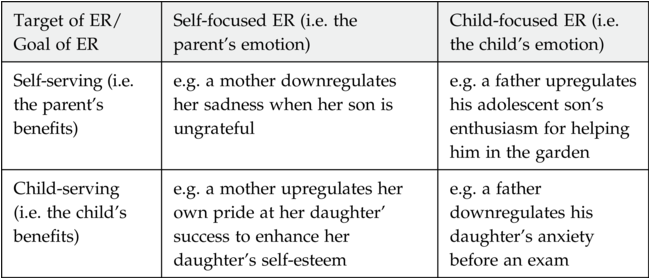

Emotion regulation (ER) refers to processes by which individuals influence which emotions they have, when they have them, and how they experience and express these emotions (Gross, Reference Gross1998, Reference Gross2015). This includes both psychological and physiological processes that monitor, evaluate, and modulate emotions in the service of individuals’ goals (Gross Reference Gross2015; Thompson, Reference Thompson1994). Notably, goals and ER processes may be within conscious awareness (explicit) or outside of it (automatic or implicit), and may occur within the individual (e.g. thoughts, physiological activation) or within the context of a relationship (e.g. when a parent provides external/coregulation to an infant by rubbing their back and cooing). It has been increasingly recognized that, whether consciously or not, regulatory processes are almost always recruited when an emotion occurs (Campos et al., Reference Campos, Frankel and Camras2004), and continuous monitoring of the situation that triggered the emotions, as well as one’s progress towards whatever the goal is, leads to the generation of new emotions and regulatory processes (Gross, Reference Gross2015; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Gatzke-Kopp, Cole and Ram2022). For example, the mother of the little girl in the grocery store story is continually monitoring her daughter’s behavior during the tantrum and assessing how close she is to her goal to move on from the cereal aisle as soon as possible (with a calm(er) daughter, and without the Lucky Charms). She realizes that she is getting closer to that goal when she sees that her daughter is calming down, and at that point a new emotion is generated, namely relief. However, this change in her daughter’s behavior also triggers another situational goal: a desire to reinforce her daughter’s compliance and ability to self-regulate. This new goal requires upregulation of positive emotions, specifically compassion to validate her daughter’s feelings and pride to offer reinforcing praise.

In integrating work on ER and parenting, the assumption is that adaptive ER will lead to optimal parenting behavior. If ER has to do with modulating emotion in order to meet goals, then adaptive ER should facilitate parents’ ability to engage in parenting behavior that will help them meet their goals in any given parent–child interaction. In many cases, this will at least partly involve what they believe is optimal for their child’s development, although much of the time, parents are managing multiple demands simultaneously, some of which may be at odds with one another. In the grocery store story, the mothers’ immediate emotional reactions to her daughter’s tantrum were frustration (at both herself and her child), embarrassment, and anxiety. However, she realized that the parenting behaviors that these emotions might lead her to – yell at her daughter or give in to the tantrum – would not be in line with her ultimate goal to teach her daughter about accepting limits, to socialize healthy ways of expressing emotion, and to self-regulate effectively.

A major challenge in this work is defining what “optimal” parenting behavior is because there arguably is no such thing. “Optimal” parenting depends on each parent’s goals for their child, based on the needs of their child, close others, and community, all in the context of their unique environment and culture (Lamborn & Felbab, Reference Lamborn and Felbab2003). The characterizations of parenting behavior measured in the parental emotion regulation (PER) literature to date are broad, from positive/negative, sensitive/insensitive, hostile/harsh, overreactive, authoritarian/authoritative/permissive, and supportive/unsupportive emotion socialization behaviors. Even the labels for many of these types of parenting carry with them an assumption about their value for children’s development (e.g. positive versus negative, sensitive versus insensitive, supportive versus unsupportive). Yet, there are cultural and contextual nuances in beliefs about parenting, emotion expression, and how parents socialize emotions in their children, as well as environmental factors (e.g. systemic racism, poverty) that may have a substantial impact on what type of parenting behavior supports a child’s development. For example, the finding linking parents’ discouragement of children’s expressions of negative emotion to socioemotional maladjustment was robust enough that this socialization strategy is categorized as an “unsupportive” parent emotion socialization strategy (e.g. see Morris et al., Reference Morris, Criss, Silk and Houltberg2017). Yet, historically the majority of this research has been conducted in White, European American samples. As emotion socialization research in Black and Latinx families has increased, it became clear that this association was not as robust as it initially seemed (Dunbar et al., Reference Dunbar, Leerkes, Coard, Supple and Calkins2017; Labella, Reference Labella2018). Recent research suggests that in Black families, parents’ suppression of their children’s expressions of anger may be associated with better child adjustment, so long as parents also engage in racial socialization in a way that gives context to their suppression of certain emotions (Dunbar et al., Reference Dunbar, Zeytinoglu and Leerkes2022).

Thus, in trying to understand what type of PER supports parenting behaviors that promote child, family, and community health, it is critical to keep in mind that designations of certain types of parenting as “optimal” or “nonoptimal” may vary substantially across contexts. In this chapter, whenever possible, we attempt to describe parenting in terms of behavioral descriptions (e.g. behaviors that encourage children to suppress emotional displays) as opposed to using terms that could be construed as value judgements (e.g. “unsupportive,” “unresponsive”); in cases where this is challenging (i.e. when reporting results of meta-analyses or review papers) we include footnotes.

3.2 Approaches to Studying PER and Parenting Behavior

Although the affective organization of parenting framework (Dix, Reference Dix1991) came about in the 1990s, scholarly interest in the intersection between emotion regulation (and dysregulation) and parenting dates back much farther. Although not directly measured, PER is implicated in the parent–child attachment relationship as well as in the large literature linking maternal depression (and other types of parental psychopathology) to parenting and child outcomes (Goodman et al., Reference Goodman, Rouse, Connell, Broth, Hall and Heyward2011; Lovejoy et al., Reference Lovejoy, Graczyk, O’Hare and Neuman2000). As researchers homed in on emotion regulation (or dysregulation) as a potential mechanism explaining links among contextual factors, parental characteristics, parenting behavior, and child outcomes, they started including more direct measures of emotion regulation in their work.

PER has been measured in a variety of different ways, including self-report measures (rating scales, interview, experience sampling), observation, behavioral tasks, and physiological measures. Furthermore, within these methodologies, PER has been operationalized in multiple ways, including (1) emotional dysregulation, (2) use of ER strategies, and (3) changes in various streams of functioning (behavior, physiological activity, etc.). We describe each of these approaches next and call attention to how with each, as the field developed, greater attention has been called to studying parents’ ER in the specific contexts of parenting rather than as a broader human skill.

3.2.1 Difficulties in Emotion Regulation/Emotional Dysregulation

To date, one of the most widely used approaches for studying PER is to measure dysregulation. A common approach is to examine parents’ self-reports on questionnaires, such as the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation scale (Gratz & Roemer, Reference Gratz and Roemer2004). These scales solicit information on the general tendency to experience alexithymia and impaired capacity for goal-directed modulation of emotions. A recent meta-analysis showed that greater self-reported difficulties in ER are associated with lower levels of positive parenting and higher levels of negative parentingFootnote 1 (Zimmer-Gembeck et al., Reference Zimmer-Gembeck, Rudolph, Kerin and Bohadana-Brown2022). A key contribution of this body of work is that the impact of ER difficulties on parenting are not unique to parents who have a psychological disorder (as previously shown in the large body of work on parental psychopathology, e.g. Lovejoy et al., Reference Lovejoy, Graczyk, O’Hare and Neuman2000). Rather, variations in emotion regulation difficulties contribute to parenting in nonclinical, community samples, as well (e.g. Buckholdt et al., Reference Buckholdt, Parra and Jobe-Shields2014; Caiozzo et al., Reference Caiozzo, Yule and Grych2018).

Notably, the questionnaires used in these studies assess general tendencies for emotional dysregulation but not difficulties with ER during parenting specifically. It makes sense that parents who have broad difficulties regulating emotions in daily life would also have difficulties regulating emotions in their role as a parent, and the research largely bears this out (see Zimmer-Gembeck et al., Reference Zimmer-Gembeck, Rudolph, Kerin and Bohadana-Brown2022). One thing that self-report measures of general emotion dysregulation cannot do, though, is reveal aspects that may be unique to the parenting context. Given that emotions and ER are contextually dependent (Barrett & Campos, Reference Barrett, Campos and Osofsky1987; Cole et al., Reference Cole, Martin and Dennis2004; Gross, Reference Gross2015), they should be studied in context whenever possible. A parent with their own childhood trauma may excel at regulating emotions in work or social contexts but may find they experience trauma reminders in the parenting context and are quick to express anger when their child has tantrums. One study examined both self-report of general difficulties in ER and observed maternal regulation during a conflict discussion task with their 8- to 11-year-old child. Interestingly, although both self-report of general dysregulation and observed dysregulation during parent–child interaction were associated with mothers’ self-report of their “unsupportive” emotion socialization behaviors (specifically with minimizing, punitive, and distress responses to children’s negative emotion as measured by the CCNES), they were not associated with one another (Morelen et al., Reference Le and Impett2016). Similarly, another study examined associations among parent self-report of global difficulties in ER and parenting behavior alongside performance on a computerized frustration tolerance task that was specific to the parenting context (Rodriguez et al., Reference Rodriguez, Baker, Pu and Tucker2017). They found that although global difficulties in ER and performance on the frustration tolerance task were both associated with parenting behavior, the two measures of emotion regulation were not associated with one another. Although there are a multitude of reasons that self-report and observed emotions or behavioral tasks might not be statistically associated, one possibility for these studies is that general measures of emotion dysregulation are capturing something different than parenting-specific ER; although they both have implications for parenting, they may not be one in the same in terms of their contributions.

3.2.2 Emotion Regulation Strategy Use

Another more focused approach to studying PER that has grown out of our understanding parental dysregulation is to examine parents’ use of specific ER strategies. Studying ER strategies is of particular interest because specific strategies can be more directly translated into real-world applications than relatively diffuse concepts like difficulties regulating emotions. For example, a finding that cognitive reappraisal (i.e. modifying one’s appraisal of a situation; Gross, Reference Gross2015) is an effective ER strategy for parents when supporting their child in a challenging, goal directed tasks (e.g. “My child is skipping items on his worksheet not because he is lazy, but because he’s having a really difficult time understanding these concepts and the worksheet reminds him of that”) could be incorporated into educational programming for parents or mental health professionals working with children. Consistent with the broader field of emotion regulation, the strategies most commonly studied in the PER literature include suppression (i.e. efforts to inhibit expression of emotion; Gross, Reference Gross2015) and cognitive reappraisal (see Zimmer-Gembeck et al., Reference Zimmer-Gembeck, Rudolph, Kerin and Bohadana-Brown2022).

Findings of studies examining ER strategies in relation to parenting behaviors have been somewhat mixed. Overall, Zimmer-Gembeck and colleagues’ (Reference Zimmer-Gembeck, Rudolph, Kerin and Bohadana-Brown2022) meta-analysis found that ER strategies considered adaptive in the wider literature had a small, but significant, association with positive parenting (r = 0.18, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.31) and negative parenting (r = −0.15, 95% CI −0.22 to −0.07) in the expected directions (see Footnote footnote 1 for parenting descriptions). Notably, when the authors reanalyzed only the studies that examined cognitive reappraisal specifically, the effect size of the relation with negative parenting was even smaller (albeit still statistically significant; r = 0.08, 95% CI 0.16 to 0.01). For suppression (which the meta-analysis considered to be part of difficulties in ER), the relation with negative parenting, the relation was smaller (although significant; r = 0.12, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.22), and the relation with positive parenting was nonsignificant (r = −0.03, 95% CI −0.12 to 0.05, Zimmer-Gembeck et al., Reference Zimmer-Gembeck, Rudolph, Kerin and Bohadana-Brown2022). Thus, the findings linking parents’ cognitive reappraisal and suppression to their parenting behaviors are less robust than the general literature, which finds cognitive reappraisal and suppression to be consistently associated with a variety of affective, cognitive, physiological, and social outcomes (Gross, Reference Gross2013).

In parallel with the importance of considering emotion dysregulation in the context of parent–child interactions, one critical consideration in interpreting the parent ER strategy literature to date is that there is variation in terms of whether studies are measuring parents’ general use of the strategies, versus parenting-specific use of the strategies. The Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (Gross & John, Reference Gross and John2003) is a widely used measure (including in the PER literature) of cognitive reappraisal and suppression that assesses one’s tendency to use these strategies in general daily life. It does not assess use of emotion regulation within the parenting context specifically, and presumably, when parents complete the questionnaire, they are answering questions based on their parenting experiences as well as experiences in other aspects of their life (e.g. work, with intimate partners, with adult family members, friends, etc.). Yet, parenting is a unique context in which one person (the parent) is responsible for the well-being of another person (Dix, Reference Dix1991; Hajal & Paley, Reference Hajal and Paley2020; Teti & Cole, Reference Teti and Cole2011), whose dependence on the parent for external regulation is greater the younger they are. Thus, it may be that strategies that are adaptive in the wider world of an adult’s life are not, in fact, adaptive when the parents’ goal is not only regulating their own emotion but also regulating their child’s.

To address this issue, Lorber (Reference Lorber2012) developed the Parent Emotion Regulation Inventory (now in its second edition, PERI-2; Lorber et al., Reference Lorber, Vecchio, Feder and Slep2017). The PERI was modeled on Gross’ Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ) and asks the same cognitive reappraisal and suppression questions, but with the initial prompt “When my child misbehaves or does something that I don’t like … ,” thus tying the ER strategies specifically to parent–child interactions. Examining relations between the ERQ and the PERI across two samples of parents of toddlers suggests that global ER strategies and parenting-specific ER strategies cannot be conflated, as their bivariate association is moderate at best (Lorber, Reference Lorber2012; Lorber et al., Reference Lorber, Vecchio, Feder and Slep2017). Furthermore, the patterns of associations between global and parenting-specific strategies differed across the two samples. In one sample, global and parenting reappraisal were moderately and significantly correlated (r = 0.56) whereas global and parenting suppression were not (Lorber, Reference Lorber2012). In the other sample, however, the opposite set of relations was found (Lorber et al., Reference Lorber, Vecchio, Feder and Slep2017).

Examinations of parenting behaviors with general versus parenting-specific ER strategies have also been mixed. Some studies have found greater PERI-measured reappraisal to be associated with lower overreactive discipline (Lorber, Reference Lorber2012), lower punitive and minimizing emotion socialization behaviors, and more supportive emotion socialization behaviors (Shenaar-Golan et al., Reference Shenaar-Golan, Wald and Yatzkar2017), whereas another found it to be unrelated to both self-reported and observed measures of overreactive and physical discipline (Lorber et al., Reference Lorber, Vecchio, Feder and Slep2017). Even more equivocal results have been found for PERI-measured suppression: whereas an early study showed that greater parenting suppression was associated with lower levels of over-reactive discipline (Lorber, Reference Lorber2012), another study showed it to be associated with higher levels of overreactive discipline (Lorber et al., Reference Lorber, Vecchio, Feder and Slep2017). A third study found no relation between suppression and parents’ emotion socialization behaviors (Shenaar-Golan et al., Reference Shenaar-Golan, Wald and Yatzkar2017).

These findings suggest that we must think critically about applying models of individual, intrinsic ER to contexts that involve two people, one of whom is (at least partially) externally regulating for the other as well as regulating for themselves. Findings from the broader ER literature show that reappraisal is preferred in low intensity emotion situations whereas emotion disengagement/distraction is preferred in high intensity situations possibly because it blocks emotion at an earlier stage of processing (Sheppes et al., Reference Sheppes, Scheibe, Suri and Gross2011, Reference Sheppes, Scheibe, Suri, Radu, Blechert and Gross2014). Given that parents are frequently regulating for two, the intensity may be high more often in parenting situations than in other contexts. Furthermore, if emotion regulation is inherently goal directed (Cole et al., Reference Cole, Martin and Dennis2004; Gross, Reference Gross2013), the study of parenting emotion regulation must consider goals not only for parents’ regulation of themselves but also of their children (for intrinsic versus extrinsic ER in parenting, see also Chapter 6). For example, momentary suppression of negative emotion in certain parenting situations is an inherent component of behavior management strategies recommended by pediatricians and psychologists for both typically developing children and for those with behavioral challenges. Parents are taught to remain neutral when actively ignoring irritating child behaviors and to use a calm voice when putting a young child in a time-out. Yet, these are the very moments in which parents often experience strong emotions (Hajal et al., Reference Hajal, Teti, Cole and Ram2019). Thus, by instructing parents to remain calm and neutral, professionals are essentially asking parents to suppress the outward expression of their emotions as a part of the enactment of positive parenting strategies. Future research on PER strategy use should center the specific context of parenting in study conceptualization and interpretation of findings.

3.2.3 Psychophysiological Processes Related to Emotion

Another approach to examining parents’ ER is to record their psychophysiology continuously while actually in the act of parenting. This approach addresses the issue of general/global ER versus parenting-specific ER, because many psychophysiological methods can be recorded relatively unobtrusively and so are suitable for moment-to-moment collection during parent–child interactions. Psychophysiological methods are also beneficial for studying emotions and emotion regulation in general because they address the bias-related issues that plague self-report, such as recall bias and social desirability bias. Furthermore, these methods can capture regulatory processes that are so quick or automatic that they occur outside of parents’ awareness (and so would be unavailable to self-report).

Another benefit of using psychophysiological methods to assess PER is that it allows us to capture change in emotion-related processes. In their paper on methodological considerations in studying ER, Cole and colleagues (Reference Cole, Martin and Dennis2004) emphasized that regulation cannot be inferred from the simple expression (or lack thereof) of any particular emotion, but requires observation of a change in emotional state. Thus, studies of ER should include precise measurement of (1) an emotion occurring and (2) regulation of that emotion. If certain psychophysiological processes are viewed as related to emotion, or to different aspects of emotional reactivity and regulation, then measuring their moment-to-moment variation over time can address this methodological challenge.

Some research groups have examined autonomic nervous system (ANS) reactivity during the act of parenting to understand parents’ emotion-related responses to parent-child interaction. The sympathetic branch of the ANS “turns on” in response to challenge and has been studied as an index of parents’ emotion-related reactivity or arousal. The ANS’s parasympathetic branch, on the other hand, is responsible for maintaining homeostasis; accordingly, shifts within the parasympathetic system have been viewed as indicators of regulatory processes. In research on PER, skin conductance level is the most commonly used measure of sympathetic nervous system activity; it is considered a physiological index of emotional reactivity or arousal. Respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA; a measure of heart rate variability based on respiration) is the most commonly used measure of parasympathetic nervous system activity; it is considered an index of physiological regulation (Leerkes & Augustine, Reference Leerkes, Augustine and Bornstein2019). Although the studies linking sympathetic activity (reactivity/arousal) directly to parenting behaviors have had mixed findings, those that measure shifts in parasympathetic activity as a measure of regulation – or better yet, studies that integrate both types of measures – appear to show more predictable associations with parenting behavior and child outcomes (Leerkes & Augustine, Reference Leerkes, Augustine and Bornstein2019). For example, Moore and colleagues (Reference Moore, Hill-Soderlund, Propper, Calkins, Mills-Koonce and Cox2009) showed that greater maternal physiological regulation during a challenging parent–infant interaction was associated with greater observed sensitivityFootnote 2 when interacting with their babies. Going a step further, studies that assess sympathetic (reactivity/arousal) and parasympathetic (regulation) activity simultaneously show that the interaction between the two is most predictive of parenting behaviors, cognitions, and child outcomes like attachment disorganization and behavior problems (Leerkes et al., Reference Le and Impett2016, Reference Leerkes, Su, Calkins, O’Brien and Supple2017). Specifically, greater maternal physiological reactivity/arousal was associated with maternal appraisals of infant behavior that supported sensitive parenting behaviorsFootnote 3 (both simultaneously and 8 months later), but only when mothers also experienced greater physiological regulation (Leerkes et al., Reference Le and Impett2016).

Although much of the work on parent physiological reactivity and regulation has not made full use of the millisecond-level data provided by common measures of parasympathetic activity (e.g. RSA), instead averaging across entire tasks or epochs of 30 seconds or more (Gatzke-Kopp et al., Reference Gatzke-Kopp, Zhang, Creavey and Skowron2022; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Gatzke-Kopp, Cole and Ram2022), some recent studies have used time-series or dynamic systems analyses to capture moment-to-moment changes in children’s and parents’ behaviors alongside parents’ physiological responding. One study examined parents’ physiological regulation and behaviors in the 10 seconds following children’s aversive behaviors (e.g. whining) during an interaction task and found that mothers’ greater physiological regulation was followed by maternal behaviors that returned the dyad to a positive state (Gatzke-Kopp et al., Reference Gatzke-Kopp, Zhang, Creavey and Skowron2022). Using a dynamic systems, time-series approach, another study showed that greater physiological regulation was associated with more responsive parenting behaviors (defined as attempts to acknowledge and address the child’s needs versus to dismiss or avoid attending to the child), which then led to a parasympathetic response indicating a return to baseline) as well as a decrease in children’s challenging behaviors (e.g. violations of task rules, negative emotion expressions; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Gatzke-Kopp, Cole and Ram2022).

In sum, measuring parental physiological processes during parent–child interaction facilitates gathering information about ongoing, parenting-specific emotion regulation in a scientifically rigorous way. Drawbacks include the inability of physiological measures to differentiate between specific emotions (e.g. is increased skin conductance associated with experiences of anger? Fear? Both?), which may have differential impacts on behavior (see further discussion of this next). Furthermore, although measurement of ongoing physiological processing may provide a methodologically rigorous way to measure emotion regulation as a modulation of activated emotions (per Cole et al., Reference Cole, Martin and Dennis2004), and to capture aspects of regulation that are outside of awareness, the only way to know whether (and which) voluntary ER strategies are used requires incorporating self-report.

3.3 Future Directions

Over the last 30 years, the study of how parents modify their emotions and how this regulation shapes their behavior in parent–child interactions has flourished. Here we have highlighted how research first captured parents’ general emotion dysregulation, teaching us that impaired emotion regulation is not unique to the clinical domain, and newer avenues of work suggest a need to focus on emotion regulation specifically in the parenting context. Further study homed in on the specific strategies parents use to regulate their emotions and how it is critical to again consider these strategies in the parenting specific context. Lastly, we described advances in capturing parents’ physiological changes during parent–child interactions. We now outline important areas of growth for the field including (1) a specific emotion approach, (2) increased attention to positive emotion regulation, and (3) ecologically valid methodological approaches when possible.

3.3.1 Specific Emotion Approach

One major gap in the PER literature to date is the lack of studies that attempt to disentangle the regulation of specific parental emotions (e.g. sadness, anger, fear, joy, pride). With very few exceptions, PER studies tend to focus on general difficulties in ER or ER strategies used to downregulate “negative emotions” or “distress” without disentangling the wide variety of negatively valenced emotions that distress may consist of. Furthermore, some studies do not explicitly measure parental distress but simply assume it based on a particular type of stressor (e.g. a child’s misbehavior), even though the same stressor may elicit different emotions in different people. The PER literature’s narrow focus on diffuse negative affect is at odds with research showing that parents’ discrete emotions are associated with different types of parenting behavior. For example, whereas parental positive affect is associated with sensitive/supportive parentingFootnote 4 (Rueger et al., Reference Rueger, Katz, Risser and Lovejoy2011), anger is associated with parenting that is characterized as harsh, hostile, or reactive (Ateah & Durrant, Reference Ateah and Durrant2005; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Field, Fox, Davalos, Malphurs, Carraway, Schanberg and Kuhn1997; Leung & Slep, Reference Leung and Slep2006; Rodriguez & Green, Reference Rodriguez and Green1997), anxiety and worry with controlling over-protectiveness and restrictiveness (Dix et al., Reference Dix, Gershoff, Meunier and Miller2004; Kaitz & Maytal, Reference Kaitz and Maytal2005), and sadness with behavior that is noncontrolling and detached from children’s goals and needs (Dix et al., Reference Dix, Gershoff, Meunier and Miller2004). Thus, if parents engage in emotion regulation at least partly to modulate the impact of their emotions on their parenting behaviors, different emotions may be regulated differently. For example, one study used hypothetical vignettes to examine complex patterns between parents’ emotional suppression and parenting style, finding that associations differed based on the specific emotion expressed by the child and felt by the parents (Martini et al., Reference Martini, Root and Jenkins2004). Lower levels of self-reported authoritarian parenting were associated with (1) mothers’ suppression of their own anger in response to their child’s sadness and fear – but not in response to child anger and (2) mothers’ suppression of their own sadness/anxiety in response to their child’s fear – but not in response to child anger or sadness (Martini et al., Reference Martini, Root and Jenkins2004). As noted by the authors, goals for parenting that are associated with authoritarian beliefs (e.g. having the parent appear dominant in the interaction, which could lead to a parent suppressing nonhostile emotions like sadness and anxiety but expressing hostile emotions like anger in the context of a child’s anger), may explain these results. Importantly, this study showed that parents regulate their own anger, sadness, and anxiety differently depending on the context and that they may do so purposely in an effort to meet specific parenting goals associated with their parenting beliefs.

It is striking that so few PER studies have examined discrete emotions; however, this may be because it would be adding yet another layer into an already complex set of processes. Furthermore, because parenting typically involves managing multiple demands, it may lead to a predominance of emotion blends (the experience of more than one emotion at a time). For example, in the grocery store story, the mother had to manage the child’s behavior, the social norms at the grocery store, the impending traffic on the way home, and long-term goals for her child’s development. This led to a blend of anger, anxiety, embarrassment, relief, and pride, each of which was regulated in a different direction (down or up) and to a different extent (e.g. all three negatively valenced emotions were downregulated but the most effort went to regulating anger because it was the most predominant emotion experienced). Furthermore, in considering specific parent emotions, we must consider the orientation of the parent emotion that is to be regulated. Parental emotions may be child oriented (i.e. experienced on behalf of the child, such as being angry at oneself for not attending to the child’s needs) or they may be self/parent oriented (e.g. on behalf of the parent, such as being angry at the child for fussing; Dix et al., Reference Dix, Gershoff, Meunier and Miller2004; Leerkes & Augustine, Reference Leerkes, Augustine and Bornstein2019; Leerkes et al., Reference Le and Impett2016). In the grocery store example, the mother experienced both types of anger, which predisposed her toward different types of parenting behaviors: anger at her daughter led to an urge to yell at her daughter, whereas anger at herself led her to consider giving in to her daughter’s demands. In this case, both of these emotions were downregulated, but specific regulatory processes may have differed.

In sum, future work on PER should consider specific parental emotions as opposed to regulation of general distress/nondistress, as this approach would increase our understanding of when different strategies may be effective and toward which goals.

3.3.2 Increased Attention to the Regulation of Positive Emotions

There remains an assumption that emotion regulation refers to the modulation of negative emotions. Though positive emotions are often referenced, there has been significantly less empirical work studying their role in parent–child interactions, and a dearth of research remains on how parents regulate their own positive emotions while spending time with family (Lindsey, Reference Lindsey2020; Paley & Hajal, Reference Paley and Hajal2022).

Historically, a bias toward negative emotions existed in both basic science and clinical research with a broader interest in providing those suffering most with relief (Carl et al., Reference Carl, Soskin, Kerns and Barlow2013; Vazquez, Reference Vazquez2017). This bias has extended to the parenting literature where studying parents’ difficulty regulating emotions such as anger, frustration, and fear has prevailed over our interest in the strategies needed for parents to express joy, contentment, or gratitude. However, summoning the feelings of pride to offer praise reinforcing the child’s leaving the Lucky Charms behind likely requires upregulation of positive emotions. Over the last decade, as recognition of the importance of studying positive emotion regulation has grown, work to integrate it into the existing emotion regulation framework has strengthened our understanding of it and a call to study it has loudened (Bryant et al., Reference Bryant, Chadwick and Kluwe2011; Carl et al., Reference Carl, Soskin, Kerns and Barlow2013; Dunn, Reference Dunn2017; Lindsey, Reference Lindsey2020; Paley & Hajal, Reference Paley and Hajal2022; Quoidbach et al., Reference Quoidbach, Mikolajczak and Gross2015). Although research on the regulation of positive emotions is growing, very little of this research has been conducted with parents, and even fewer examined links between parents’ positive ER and parenting behavior. Given the importance of this emerging area of research, we briefly describe the prevailing conceptualizations of positive ER in the field, highlighting studies that have focused on the family context, and suggesting avenues for future research on parental regulation of positive emotions.

Savoring is the strategy most often named in upregulating positive emotions (e.g. Bryant, Reference Bryant1989, Reference Bryant2021; Quoidbach et al., Reference Quoidbach, Berry, Hansenne and Mikolajczak2010) and subsumes more specific terms such as maximizing (Gentzler et al., Reference Gentzler, Kerns and Keener2010), amplification (e.g. Le & Impett, Reference Le and Impett2016), and capitalization (e.g. Peters et al., Reference Peters, Reis and Gable2018). Savoring can differ based on the emotion upregulated: reflecting on one’s good feelings for happiness, reflecting on one’s good qualities for pride, counting one’s blessings for gratitude, marveling for awe (e.g. Bryant, Reference Bryant2003; Gentzler et al., Reference Gentzler, Palmer and Ramsey2016; Giuliani et al., Reference Giuliani, McRae and Gross2008; Sheldon & Lyubomirsky, Reference Sheldon and Lyubomirsky2006). Dampening or minimizing are the terms used most frequently to refer to the downregulation of positive emotions (Gentzler et al., Reference Gentzler, Palmer and Ramsey2016; Quoidbach et al., Reference Quoidbach, Berry, Hansenne and Mikolajczak2010).

Within the study of families, more attention has been called to children’s regulation of positive emotions and the parenting behaviors that socialize it than attention to how parents modulate their own positive emotions. For example, in an observational study of family daily life, children’s expressions of positive emotions were sustained by parents’ own positive emotion expression, physical touch, and further engagement (Bai et al., Reference Bai, Repetti and Sperling2016). In the same sample, mothers who expressed more compassion, over and above other positive emotions, had children who expressed more positive emotion overall (McNeil & Repetti, Reference McNeil and Repetti2021). In an observed interaction task, mothers active-constructive responses to adolescents‘ positive affect in a shared positive planning event uniquely predicted youths’ reported use of positive emotion regulation strategies (Fredrick et al., Reference Fredrick, Mancini and Luebbe2019). Both questionnaire and observational studies support the associations between parental dampening of youth positive affect, youth engagement in dampening strategies, and youth depressive symptoms (Nelis et al., Reference Nelis, Bastin, Raes and Bijttebier2019; Raval et al., Reference Raval, Luebbe and Sathiyaseelan2019; Yap et al., Reference Yap, Allen and Ladouceur2008). For example, a study focused on clinically depressed adolescents compared with healthy controls found that both mothers and fathers of adolescents with depression were less likely to accept youths’ positive affect and fathers were less likely to respond to their youths’ positive affect with strategies that were likely to maintain or enhance it (Katz et al., Reference Katz, Shortt, Allen, Davis, Hunter, Leve and Sheeber2014). Though parental responses to children’s positive affect appears to shape children’s ability to appropriately maintain positive emotions and in turn impacts child psychopathology, less is known about parents’ engagement or lack thereof in their own positive emotion regulation.

Of the few studies that explicitly examine parents’ regulation, there is some evidence that parents’ regulation of positive emotions is associated with aspects of their parenting behaviors, including emotion socialization behaviors. In a multimethod study of mothers and school-age children (Moran et al., Reference Moran, Root, Vizy, Wilson and Gentzler2019), mothers’ self-reported savoring of their own hypothetical positive events was positively associated with self-report and child report of parents’ coaching of savoring, and self-reported encouraging of child’s positive affect. Similarly, mothers’ self-reported dampening of their own hypothetical positive events was positively associated with their self-reported coaching of dampening in their child, and self-reported discouraging of child’s positive affect. In a related study with the same sample of mother–child dyads, mothers who reported more intense positive affect in response to their own hypothetical events were observed using more positive affect-related words in a discussion task with their child (Morrow et al., Reference Morrow, Gentzler, Wilson, Romm and Root2021).

Experimental studies designed to test the effectiveness of interventions targeting positive emotion regulation can also provide information about associations between PER and parenting behavior. A recent randomized controlled trial tested the impact of a parental savoring intervention on parenting behavior in families with young children. Furthermore, the study design allowed for comparing the impact of general positive ER to parenting-specific positive ER, as it tested the impact of training parents to savor aspects of closeness in the parent-child relationship (termed “relational savoring”; Borelli et al., Reference Borelli, Smiley, Kerr, Hong, Hecht, Blackard, Falasiri, Cervantes and Bond2020). In comparison to participants randomized to a general positive emotion savoring condition, parents randomized to the relational savoring condition showed greater pre- to postintervention increases in observed sensitivity to their toddlers’ cues during a teaching task (Borelli et al., Reference Borelli, Kerr, Smiley, Rasmussen, Hecht and Campos2022). These findings support the notion that parents’ regulation of positive emotions has an impact on their parenting behavior but only when regulation of positive emotions specific to the parenting context is considered.

Thus, regulation of positive emotions is critical to consider in the study of PER, and there are many avenues within this area to explore. For example, ability to effectively regulate positive emotions is likely key to being able to perform the parenting behavior strategies recommended in parenting interventions designed to treat child pathology and increase the quality of the parent-child relationship. For example, the PRIDE skills in Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT; Eyberg & Funderburk, Reference Eyberg and Funderburk2011) includes both “praise” and “enjoy,” which are expressions of pride and joy. Studies are needed to examine the role parental regulation of positive emotions plays in parents’ ability to engage in these skills and other positive parenting behaviors. There is also some evidence that upregulation of positive emotion for parents may have a negative impact on parenting behavior. In a diary study, parents who were assigned to reflect on a time when they amplified their positive emotion in an interaction with their child reported less responsiveness to their child’s needs (Le & Impett, Reference Le and Impett2016). An important caveat to highlight in the study of positive emotion regulation in parents is that amplification of positive emotions and minimizing of negative emotions may not always be adaptive. More studies are necessary to understand the effort and costs associated with parents’ modulation of positive feelings. Finally, examination of positive emotions from a specific emotions approach – differentiating among emotions such as joy, pride, compassion and gratitude – would strengthen our understanding of the interpersonal emotion dynamics happening within families (Repetti & McNeil, Reference Repetti, McNeil, Randall and Schoebi2018).

3.3.3 Ecologically Valid Assessment

Studies cited throughout this chapter have used self-report questionnaires, multiple informants, observation of laboratory interactions and physiological measures to teach us about how PER and parenting behavior are interrelated; we have described many of the strengths and weaknesses of these methodologies. One area of growth for the field, especially as it increases its testing of emotion regulation specifically in the context of parenting, is to capitalize on technological advances that allow for increased access to life as it is lived within the family. Two key methodologies that would help researchers maximize the ecological validity of their findings and decrease the gap between what is captured and the phenomena of interest are experience sampling method (Hektner et al., Reference Hektner, Schmidt and Csikszentmihalyi2007) or related repeated sampling techniques and naturalistic observations of family life.

Experience sampling methods have benefits that include reducing memory biases and helping test the phenomena in its natural environment, such as in the family home (Reis, Reference Reis, Mehl and Conner2012). They also allow for new questions to be asked such as the variability of emotion regulation strategies used in daily life (Blanke et al., Reference Blanke, Brose, Kalokerinos, Erbas, Riediger and Kuppens2020). In one study of emotion regulation in mothers of toddlers, mothers were phoned four times a day for 6 days (Hajal et al., Reference Hajal, Teti, Cole and Ram2019). These brief interviews allowed for the assessment of mothers’ in-the-moment emotions, motivations, and behaviors and enabled the disentangling of associations between these three simultaneously occurring phenomena.

When the goal is to capture behavior, such as how parents interact with their children, naturalistic observation of families in the home and community settings should be considered. As compared with questionnaire data, parent–child interaction tasks in the laboratory allow for direct observation of parenting behavior; they reduce bias with coding from impartial raters; and the structure of the situation can help isolate a variable of interest (Cole et al., Reference Cole, Martin and Dennis2004). However, they may suffer from being conducted in an unfamiliar setting and from occurring over a limited time in which a parent might display what they are capable of rather than how they regularly act (Repetti et al., Reference Repetti, Wang, Sears, Grzywacz and Demerouti2013). One improvement may be moving these structured tasks into the home and capturing them over telehealth where the natural chaos of the home environment (distracting other toys, a sibling needing help) may pervade and a more accurate portrayal of daily parenting behavior may be captured. A further improvement may be to capture daily life as it is lived (e.g. Campos et al., Reference Campos, Wang, Plaksina, Repetti, Schoebi, Ochs and Beck2013; Teti et al., Reference Teti, Kim, Mayer and Countermine2010) in the home with the use of new, uninvasive recording tools, such as smarthome technology (Nelson & Allen, Reference Nelson and Allen2018). A study conducted by the Center on the Everyday Lives of Families recorded families across 4 days in their homes, cars, and communities as they went about their daily life (Ochs & Kremer-Sadlik, Reference Ochs and Kremer-Sadlik2013). This type of naturalistic data allows for the investigations of frequency of behavior that is hard to capture accurately with other methods. For example, on average mothers in the family setting expressed gratitude over four times an hour, fathers expressed pride almost three times an hour and children expressed amusement around twice an hour (McNeil & Repetti, Reference McNeil and Repetti2021). Recording families in their daily lives allows us to capture, not how parents perceive their parenting style or how they act for short bursts in unfamiliar settings, but parenting behaviors as they naturally occur and if they naturally occur.

3.4 Conclusion

In sum, 30 years of rigorous scientific investigation provides support for Dix’s (Reference Dix1991) theory of parenting as an “affectively organized” process and concurs that parents’ regulation of emotion is key to their engaging in parenting behaviors aligned with their goals. As this robust body of work continues to grow, avenues for future research include increased attention to parents’ ER as measured in parenting specific contexts; multimethod approaches that integrate self-report, physiology, and naturalistic observation; and a shift away from a broad conceptualization of negative emotions or affect to the full spectrum of specific emotions (e.g. sadness, anger, fear, contentment, excitement, pride, gratitude, awe).

“Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.”

Emotion regulation processes are prone to disruption during periods of transition. Such processes may occur during negative events, as well as through transitions considered common and natural or during periods perceived as positive. Those undergoing transitional periods experience many emotions that are often conflicting and complex (Stern & Bruschweiler-Stern, Reference Stern and Bruschweiler-Stern1998), thus requiring specific tools. The transition into parenthood is often perceived as a positive experience involving aspects of growth and development (Mercer, Reference Mercer2004). Nevertheless, it is also a time of adjustment during which emotion regulation plays a particularly strong role due to the emotionally demanding nature of parenthood. Adjustment and adaptation to parenthood are likely challenging for all individuals. However, in this chapter, I focus on survivors of childhood maltreatment, who may find this period especially challenging (e.g. DiLillo, Reference DiLillo2001).

4.1 Childhood Maltreatment: A Dark Cloud during the Transition into Parenthood

According to the World Health Organization, child maltreatment (CM) is abuse and neglect of individuals under 18 years of age. It includes all forms of physical and/or emotional ill-treatment, sexual abuse, neglect or negligent treatment, or commercial or other exploitations that result in actual or potential harm to the child’s health, survival, development, or dignity in the context of a relationship of responsibility, trust, or power (World Health Organization, 2014). CM is highly prevalent and globally widespread among both clinical and nonclinical populations. A meta-analysis of more than two hundred studies among nonclinical populations identified that approximately 23% of the participants reported childhood physical abuse, 13% reported childhood sexual abuse, 36% reported emotional abuse, 16% reported physical neglect, and 18% reported emotional neglect (Stoltenborgh et al., Reference Stoltenborgh, Bakermans‐Kranenburg, Alink and van IJzendoorn2015).

The long-lasting nature of the negative psychological effects of CM has been previously established by studies that have examined the impacts of CM in adulthood. Among these effects are a higher risk for depression (Talmon et al., Reference Talmon, Horovitz, Shabat, Haramati and Ginzburg2019), anxiety disorders (Talmon et al., Reference Talmon, Dixon, Goldin, Heimberg and Gross2020), eating disorders (Talmon & Tsur, Reference Talmon and Tsur2021; Talmon & Widom, Reference Talmon and Widom2021), self-harm behaviors (Talmon & Ginzburg, Reference Talmon and Ginzburg2018b), and other manifestations of distress (Talmon & Ginzburg, Reference Talmon and Ginzburg2017, Reference Talmon and Ginzburg2018a, Reference Talmon and Ginzburg2018b, Reference Talmon and Ginzburg2019b; Talmon et al., Reference Talmon, Uysal and Gross2022). Further studies have also suggested that those who were maltreated as children are at significant risk for several adverse mental health outcomes during adulthood, including depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and substance abuse (Famularo et al., Reference Famularo, Kinscherff and Fenton1992; Livingston et al., Reference Livingston, Lawson and Jones1993; McLeer et al., Reference McLeer, Dixon, Henry, Ruggiero, Escovitz, Niedda and Scholle1998).

Individuals exposed to CM are often at the receiving end of continuous negative messages that may stimulate their sense of shame (Talmon & Ginzburg, Reference Talmon and Ginzburg2017), which can endure many years after the traumatic experience(s) have ended. These messages may have been delivered explicitly or implicitly and possibly relied on the child’s perception of having been involved in behaviors considered to be deviant, disgraceful, or dishonorable (Finkelhor & Browne, Reference Finkelhor and Browne1985; Rahm et al., Reference Rahm, Renck and Ringsberg2006; Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Droždek and Turkovic2006). Consequently, abusive experiences may affect children’s self-perceptions, and they may begin to perceive themselves as evil, worthless, or shameful (Finkelhor, Reference Finkelhor1987; Janoff-Bulman, Reference Janoff-Bulman2010). For example, O’Mahen et al. (Reference O’Mahen, Karl, Moberly and Fedock2014) concluded that CM is an established distal risk factor that triggers the development of proximal maladaptive cognitive and behavioral styles, increasing the risk for individual vulnerability to psychological dysfunction. Subsequently, when child survivors of CM transition into adolescence and adulthood, in particular during major life changes, such as the transition to parenthood, some of their previous core beliefs about themselves might be triggered and reactivated.

4.2 Parenting against the Backdrop of Childhood Maltreatment

Becoming a parent is a very common life transition. In general, this transition can elicit emotions ranging from positive, such as joy, love, contentment, pride, and relief, to negative, such as anger, frustration, disappointment, worry, fear, and guilt (Bradley et al., Reference Bradley, Hurwitz, Harvey, Hodgson and Perugini2013). These feelings may be oriented toward oneself vis-à-vis the child (e.g. being angry at oneself for not sufficiently attending to the child’s needs) or directed toward the child (e.g. being angry at the child for fussing) (Dix et al., Reference Dix, Gershoff, Meunier and Miller2004; Leerkes et al., Reference Leerkes, Su, Calkins, Supple and O’Brien2016). Therefore, the transition into parenthood may constitute the basis for various manifestations of growth and well-being, but at the same time for various manifestations of distress.

Surprisingly, research on the transition into parenthood against the backdrop of CM is limited, and the existing studies have focused on aspects other than these parents’ adjustment and well-being. Instead, the topic has been explored from the children’s perspective, mainly regarding how the parents’ history of maltreatment may affect their children. This phenomenon has also been examined in relation to the obstetric outcomes of women with a history of abuse and the implications of CM history for the newborn and their development (e.g. Buss et al., Reference Buss, Entringer, Moog, Toepfer, Fair, Simhan, Heim and Wadhwa2017). Other researchers have adopted a similar perspective, aiming to understand the cycle of abuse and the mechanism that “turns” a maltreated child into an abusive parent (e.g. Bly, Reference Bly1988; Dixon et al., Reference Dixon, Browne and Hamilton‐Giachritsis2005). Additionally, some studies have focused on CM and its impact on parental decision-making skills. In these studies, it was found that maltreated mothers were often young (e.g. Anda et al., Reference Anda, Whitfield, Felitti, Chapman, Edwards, Dube and Williamson2002; Becker-Lausen & Rickel, Reference Becker-Lausen and Rickel1995) and demonstrated poorer parenting skills and abilities than mothers who were not maltreated as children (e.g. DiLillo & Damashek, Reference DiLillo and Damashek2003).

The absence of studies that focus on the experiences of parents with a history of CM is apparent. Based on the existing studies, however, adults with a history of CM appear to have specific challenges in transitioning into parenthood. Encouragingly, research over the past few years has increasingly begun to move in a different direction that considers the previously abused parent as the focal point of investigation. Recent findings from a systematic review have suggested that, indeed, CM is a risk factor for additional challenges when transitioning into parenthood (Christie et al., Reference Christie, Talmon, Schäfer, De Haan, Vang, Haag, Gilbar, Alisic and Brown2017). Namely, during the transition into parenthood, those with a history of CM may experience a range of mental health problems, adverse physical effects, and more negative views of their child (or children), compared to parents without a history of CM. In some cases, those with a history of CM have also reported negative experiences regarding their identity as a parent, manifested by high levels of self-criticism and low levels of self-esteem. In addition, recent studies have pointed to the implications of CM for a plethora of distress arenas, including an increased sense of fear of giving birth among mothers-to-be (Talmon & Ginzburg, Reference Talmon and Ginzburg2019a), a lower sense of maternal efficacy, and a heightened risk for developing postpartum depression (Greene et al., Reference Greene, Haisley, Wallace and Ford2020; Schuetze & Eiden, Reference Schuetze and Eiden2005; Talmon et al., Reference Talmon, Horovitz, Shabat, Haramati and Ginzburg2019). One potential explanation for the challenges faced by parents with a history of CM is that exposure to CM often impairs one’s emotion regulation (ER), which is a crucial tool for resilience prior and during parenthood.

4.3 Childhood Maltreatment and Its Impact on the Development of Emotion Regulation

Emotion regulation is defined as “how we try to influence which emotions we have, when we have them, and how we experience and express these emotions” (Gross, Reference Gross, Lewis, Haviland-Jones and Feldman Barrett2008, p. 497). Eisenberg et al. (Reference Eisenberg, Spinrad and Wilkens2010) refer to childhood as a critical period for the development of ER skills and regulatory processes through which individuals modulate their emotions, both consciously and unconsciously (Bargh & Williams, Reference Bargh, Williams and Gross2007; Rottenberg & Gross, Reference Rottenberg and Gross2003), to effectively respond to environmental demands (Gross & Muñoz, Reference Gross and Muñoz1995). The severe psychological implications of CM may reflect damage to a significant internal mechanism of ER (Dvir et al., Reference Dvir, Ford, Hill and Frazier2014). Indeed, a clear link has been established between CM and impaired ER. Specifically, children exposed to CM might have their development or effective behaviors undermined. Therefore, they could be more susceptible to adopting ineffective ER strategies that, subsequently, have a negative impact on emotional functioning (Briere & Jordan, Reference Briere and Jordan2009; Shields & Cicchetti, Reference Shields and Cicchetti2001; Spasojević & Alloy, Reference Spasojević and Alloy2002). Previous studies in which this link was examined revealed that CM exposure was commonly correlated with maladaptive ER strategies, such as behavioral avoidance, rumination, and brooding (O’Mahen et al., Reference O’Mahen, Karl, Moberly and Fedock2014).

Behavioral avoidance, which includes various behavioral attempts to reduce environmental events that are emotionally punishing (Aldao et al., Reference Aldao, Nolen-Hoeksema and Schweizer2009), has been identified as a likely occurrence in environments with low positive reinforcement and high negative reinforcement and punishment (Manos et al., Reference Manos, Kanter and Busch2010). Behavioral avoidance tends to take place in neglectful and abusive environments where positive emotions are not reinforced, leading children to develop negative coping mechanisms to survive their environment. Given that the literature has shown an association between CM and behavioral avoidance, it can be argued that such avoidant characteristics are endemic to abusive and neglectful environments. As such, children experiencing CM end up engaging in withdrawal behaviors, as well as using avoidance as a mechanism to reduce emotional and physiological arousal. Although these connections have not been examined directly, it seems plausible that this type of ER is highly associated with exposure to a history of abuse and/or neglect.

Childhood emotional abuse and neglect, as well as sexual abuse, have also been linked with rumination, which refers to an individual’s repetitive focus on the causes and consequences of experiences and emotions (Crane et al., Reference Crane, Barnhofer, Visser, Nightingale and Williams2007; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., Reference Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco and Lyubomirsky2008; Spasojević & Alloy, Reference Spasojević and Alloy2002). Explicitly, rumination is an ER strategy potentially developed among those exposed to CM as a result of their experiences. Thus, the inconsistency, manipulation, and uncertainty associated with emotional and sexual abuse might shed light on the development of the tendency to ruminate (Conway et al., Reference Conway, Singer and Tagini2004; Spasojević & Alloy, Reference Spasojević and Alloy2002).

As previously mentioned, another common negative ER strategy is brooding. Treynor et al. (Reference Treynor, Gonzalez and Nolen-Hoeksema2003) identified brooding (i.e. the maladaptive component of rumination, characterized by feeling worthless in consideration of an unattained standard) as being associated with a history of CM. In addition to these findings, strong links have been reported between emotional abuse and concurrent depressive symptoms, with brooding acting as a mediator in this relationship (Raes & Hermans, Reference Raes and Hermans2008).

It is important to view CM as a springboard for ER strategies, whether positive or negative. Although using negative ER coping strategies may be a matter of survival for children during the maltreatment (e.g. a child does whatever they can to avoid meeting their father in the house to avoid being beaten), as adults, they may bring these strategies into parenthood, when ideally they should no longer need them. Perpetuating the use of these negative strategies can be potentially damaging for themselves and their loved ones, namely the child who is now involved. Given the available literature on the linkage between CM and dysregulated ER, it is not surprising that some individuals with a history of CM face challenges with ER processes during the transition into parenthood as well as during parenthood. This is particularly apparent when observing the transition into parenthood through the lens of exposure to childhood abuse and neglect and the psychological weight of their previous trauma (Hajal & Paley, Reference Hajal and Paley2020).

4.4 Emotion Regulation among Parents Who Have Experienced Childhood Maltreatment

Parenting is a particularly unique and challenging milieu during which a person is responsible for and directly influences the emotional well-being of another, often requiring sophisticated ER abilities. Indeed, children are hugely impactful on their parents’ emotional lives (Rutherford et al., Reference Rutherford, Wallace, Laurent and Mayes2015) and evoke a broad range of emotions in both mothers and fathers (Hajal & Paley, Reference Hajal and Paley2020), which call for the parents’ use of ER. This is true in both direct parent–child interactions, such as times of achievement or tantrums, and indirect parent-related tasks, such as thinking about one’s children when they are not present or preparing and developing activities for them. Such a connection and the related responsibilities may be daunting against the background of CM as the parents may not have experienced healthy emotional responses and attachment patterns themselves in their childhood.

The examination of attachment patterns of parents with a CM history forged with their caregivers in childhood is important in understanding the potential repetitive cycle of such behaviors. Parents with a history of CM often have a heightened risk of attachment difficulties with their children (Khan, Reference Khan2017). For example, it was found that some mothers were unable to provide a secure emotional connection for their young children as a result of their experiences of maltreatment (Main & Solomon, Reference Main, Solomon, Greenberg, Cicchetti and Cummings1990; Pajulo et al., Reference Pajulo, Pyykkönen, Kalland, Helenius, Punamäki and Suchman2012). It has also been suggested that mothers who experienced CM and had insecure attachment patterns with their caregivers were more likely to have difficulties bonding with others in general and, specifically, to have more disruptions in their attachments to their children (Cicchetti & Barnett, Reference Cicchetti and Barnett1991).

Given that the quality of the parent–child attachment is critical for the child’s ability to build healthy and adaptive relationships with other individuals over time (Kerns & Barth, Reference Kerns and Barth1995), CM may have long-term negative effects on parental regulatory processes. For example, mothers’ experience of rejection by their caregivers was found to be related to their rejection of their own children (Fonagy et al., Reference Fonagy, Steele and Steele1991). Furthermore, in some cases, this behavior has been linked to their children’s avoidant behavior.

Another link that connects CM history and patterns of insecure and anxious mother–child attachment is maternal psychopathology, particularly depression, which is an influencing factor in ER processes (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Cohen, Johnson and Smailes1999; Hipwell et al., Reference Hipwell, Goossens, Melhuish and Kumar2000; Seng et al., Reference Seng, Sperlich, Low, Ronis, Muzik and Liberzon2013). It has been reported that women who experienced CM were three times more likely to develop depression than women who had not experienced CM (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Cohen, Johnson and Smailes1999). Maternal depression, in turn, has a negative effect on the parenting of young children (Goodman, Reference Goodman2007) as well as mother–child attachment (Hipwell et al., Reference Hipwell, Goossens, Melhuish and Kumar2000; Martins & Gaffan, Reference Martins and Gaffan2000). It should be noted that a limitation of this finding relates to the difficulty in determining whether parenting performances are a direct reflection of the parents’ own childhood experiences or evidence of their attempts to navigate between their own struggles to overcome the impact of the abuse and the demands of parenting. In addition to insecure attachment and depression being individually assessed, researchers have also found significant associations between mothers’ depression and insecure and anxious mother–child attachment (Hipwell et al., Reference Hipwell, Goossens, Melhuish and Kumar2000; Muzik et al., Reference Muzik, Bocknek, Broderick, Richardson, Rosenblum, Thelen and Seng2012). According to Perry (Reference Perry2001), mother–child bonding is part of the process through which attachment is formed. Given that researchers have found significant associations between mothers’ depression and problematic mother–child bonding, it could be that depression is a significant predictor of developing an insecure attachment between mother and child.

Another aspect of parenting that can be impacted considerably by the combined factors of a history of CM, anxious attachment, and depressive symptoms is parental self-efficacy (PSE). PSE is “the beliefs a parent holds of their capabilities to organize and execute the tasks related to parenting a child” (Montigny & Lacharité, Reference Montigny and Lacharité2005, p. 387). Indeed, major depression has been found to mediate the relation between attachment insecurity (i.e. anxious and avoidant attachment) and PSE. This could be because severe depression leads to lack of interest and, therefore, an inability to carry out daily functions for oneself and one’s child. Attachment anxiety and avoidance have also been found to predict low PSE through the mediating pathway of depression (Kohlhoff & Barnett, Reference Kohlhoff and Barnett2013). Such findings are consistent with those from a previous study (Caldwell et al., Reference Caldwell, Henshaw and Taylor2010) in which an association was found between early maladaptive parenting experiences and PSE. Moreover, these findings also relate to the significant association between maternal depression and attachment insecurity in the development of PSE.

These findings align with prior research suggesting that maternal attachment vulnerability can have a prominent role in predisposing women to early PSE difficulties, particularly in the presence of maternal depression. Dix et al. (Reference Dix, Gershoff, Meunier and Miller2004) explored the dynamics of families in which a depressed parent was present. They concluded that depressed mothers tended to be disengaged during conflicts with their child, and if the child’s behavior became highly aversive, the mothers displayed a high degree of distress. These findings suggest that parents with depressive symptoms exhibit both disengaged and overactive parenting behaviors that do not lead to healthy parent–child dynamics.

Aside from the apparent influence of depression in various contexts of ER during parenting, other psychopathological conditions like borderline personality disorder (BPD) may also affect these processes. BPD is fundamentally a developmental disorder, characterized by disturbances in ER processes (Herman & van der Kolk, Reference Herman, van der Kolk and van der Kolk1987), with a well-established etiology of childhood abuse history and insecure attachment during childhood (Prados et al., Reference Prados, Stenz, Courtet, Prada, Nicastro, Adouan, Guillaume, Olié, Aubry and Dayer2015). The characteristics of those diagnosed with BPD are similar to those diagnosed with complex posttraumatic stress disorder. Specifically, the main manifestation is severe disturbances in affect (emotion) and impulse control, with impairments in interpersonal relationships and sense of self, which are all crucial elements for healthy functioning as a parent.

The connection between parenting outcomes (e.g. parenting stress, feelings of competence, and discipline strategies) stemming from depression and individual types of CM, such as a history of childhood sexual abuse (CSA), has also been examined in various studies. Schuetze and Eiden (Reference Schuetze and Eiden2005) reported that women with a history of CSA who experienced depression and/or partner violence as adults were at the greatest risk for adverse parenting outcomes, including negative maternal attitudes and disciplinary strategies. Moreover, it was found that CSA was associated with increased maternal depression and increased partner violence. CSA, maternal depression, and current partner violence were also linked with more negative parental perceptions and punitive discipline. Therefore, the experience of CM – in this case, specifically CSA – is significantly linked with depression and partner violence, which further predicts negative parenting outcomes. However, maternal depression and domestic violence not only affect the involved adults and their parental attitudes but also hold additional risks for negative implications in the development of the children present (Kitzmann et al., Reference Kitzmann, Gaylord, Holt and Kenny2003; Petterson & Albers, Reference Petterson and Albers2001). It should be noted that the literature has primarily focused on mothers’ experiences of this transition rather than fathers’, yet a study that focused on the impact of CM on fathers found that fathers with maltreatment histories were also at risk of developing psychopathological symptoms, such as anxious and depressive feelings, during the transition into parenthood (Skjothaug et al., Reference Skjothaug, Smith, Wentzel-Larsen and Moe2014).

4.5 Childhood Maltreatment, Emotion Regulation, and Parenting: Implications for the Child

The effects of CM do not end with the parents and often carry over to their children, as CM is known to have intergenerational effects. According to Chamberlain et al. (Reference Chamberlain, Gee, Brown, Atkinson, Herrman, Gartland, Glover, Clark, Campbell, Mensah, Atkinson, Brennan, McLachlan, Hirvonen, Dyall, Ralph, Hokke and Nicholson2019), the perinatal period is critical for parents with a history of childhood maltreatment trauma. Parents may experience a “triggering” of trauma responses during perinatal care or when caring for their distressed infant. The long-lasting relational effects of their tumultuous past may then impede the parents’ capacity to nurture their children, leading to intergenerational cycles of trauma. Moreover, according to Haapasalo and Aaltonen (Reference Haapasalo and Aaltonen1999), one factor implicated in the etiology of CM is the parents’ own childhood experiences of abuse. It is estimated that a maternal history of abuse accounts for up to one third of the variance predicting CM.

Parents who have experienced some form of abuse during their lifetime are more likely to engage in negative responses and abusive behavior toward their children than parents who have not experienced abuse (Dixon et al., Reference Dixon, Browne and Hamilton‐Giachritsis2005). Such responses and behaviors could be considered an instance of failed ER. However, clear evidence regarding the mechanisms involved in the intergenerational transmission of CM is still lacking (Ertem et al., Reference Ertem, Leventhal and Dobbs2000). Nevertheless, it is known that mothers who were abused have a lower threshold for tolerating their children’s misbehavior than mothers without such a history. This lower threshold can manifest in the use of harsh discipline (Pears & Capaldi, Reference Pears and Capaldi2001). Furthermore, this reactive propensity can create a situation in which even minor infractions are likely to set off a series of negative mother–child interactions. By way of explanation, it may be that parents who failed to discipline their children experience higher stress and frustration levels in dealing with their children than those with better discipline skills. When this stress is combined with a history of physical abuse, the outcome is more likely to result in the transmission of abuse from one generation to the next (Pears & Capaldi, Reference Pears and Capaldi2001).

Parental CM history has also been known to increase the risk for nonabusive yet poor caregiving. In this case, children are not provided with adequate opportunities to observe healthy parenting behaviors. In addition, a mother’s CM history has been found to compromise her ER abilities, impairing her capacity to respond sensitively to her child’s needs (DiLillo & Damashek, Reference DiLillo and Damashek2003). Such responses include hostility, intrusiveness, inconsistency, decreased involvement, and rejection (e.g. Bailey et al., Reference Bailey, DeOliveira, Wolfe, Evans and Hartwick2012).