The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) has long fascinated Western observers, more often than not out of a sense of misguided curiosity. Owing to imperialism, Orientalism, and enduring stereotypes, commentary has revolved around a central query: Why is the region and its people so “backward”? The social sciences have remained focused on this question, albeit in a modified form, since the fall of the Soviet Union (Bayat Reference Bayat2013; Munif Reference Munif2020). As researchers looked optimistically to a post-1989 future that appeared to be liberalizing, they asked why the wave of democracy sweeping the formerly colonized world had bypassed the MENA region. The answer provided, in one form or another, was that regimes led by autocrats, kings, and presidents-for-life were too powerful and the people too weak – too loyal, apathetic, divided, and tribal – to mount a credible challenge to authoritarian rule.Footnote 1

Such a view errs, of course, by overlooking how countries across the MENA region have given rise to social movements for liberation, equality, and human rights throughout modern history (Bayat Reference Bayat2017; Gerges Reference Gerges2015). Whether emerging from the gilded elite or the grassroots, its people have always fought against foreign rule and domestic tyranny (Bayat Reference Bayat2013). Even so, mass mobilization against enduring dictatorships seemed unlikely after the “Global War on Terror,” launched by the United States and its allies after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, made friends out of former enemies. Foreign powers fed dictatorships in places such as Egypt, Libya, and Yemen billions of dollars’ worth of aid and weapons. They also cooperated with so-called enemies, such as the Assad regime in Syria, to render and torture suspects of terrorism. By 2010, autocrats augmented by oil wealth had Western nations so cozily in their pockets that their confidence in perpetual rule was sky high.

With so much attention focused on authoritarian durability, it is little wonder that the revolutions to follow caught scholars and governments by surprise (Bamyeh and Hanafi Reference Bamyeh and Hanafi2015). This new era of revolt began in Tunisia in December 2010; within weeks, demonstrations against corruption and repression had spread to Egypt, Yemen, Libya, Syria, and Bahrain. These uprisings, which have become known as the “Arab Spring,”Footnote 2 spanned from the sapphire-blue waters of the Mediterranean coast to the green highlands of the Arabian Peninsula. As tens of thousands of ordinary people demanded their dignity by marching in the streets against corruption and abuse, popular movements and insurgencies destabilized regimes thought to be unshakable. The conflicts that ensued produced both improbable triumphs through selfless heroism and devastating losses through abject slaughter. But well before this wave gave rise to resurgent dictatorships and civil wars (Lynch Reference Lynch2016), the masses shook the earth with rage and made dictators quake with fear.

Revolutions are rarely neatly confined to their places of origin, however. They also galvanize anti-regime activists in the diaspora around the globe, and the Arab Spring was no exception. Diaspora mobilization for the Arab Spring was no trivial matter. Long before foreign governments and international organizations jumped in to support revolutionaries, ordinary emigrants, refugees, and their children protested in Washington, DC, London, and New York City against their home-country regimes; channeled millions of dollars’ worth of aid to poorly equipped insurgencies and beleaguered refugees; and traveled homeward to join the revolutions as rescue workers, interpreters, and fighters. Diaspora activists’ efforts to help their compatriots under siege not only heralded a new wave of transnational activism, but exposed regimes’ crimes against humanity and saved lives on the ground. Their mobilization against authoritarianism also signified a new phase in community empowerment and collective action, particularly among those who had grown up in places where speaking out against ruling dictatorships could get a person imprisoned, tortured, or killed.

Although the Arab Spring uprisings are well-known, the role that diaspora movements played in this revolutionary wave is not. This is not surprising, given the guiding assumption among social scientists that protesters must be present – proximate, in person, and ready to storm the gates – to challenge authoritarians.Footnote 3 As economist Albert Hirschman (Reference Hirschman1970) describes in his hallmark work Exit, Voice, and Loyalty, populations aggrieved with their governments can do one of three things. They can either remain loyal and hope for the best, voice their dissent at home through protest – a high-risk strategy in authoritarian contexts – or exit, thereby voting against authorities with their feet. Hirschman argues that exit in the form of emigration, whether forced or voluntary, decimates the potential for voice and social change.Footnote 4 By breaking up dissident networks and separating leaders from their adherents, exit acts as a safety valve for regimes by releasing pressure from below, thereby reducing “the prospects for advance, reform, or revolution” (Hirschman Reference Hirschman and Hirschman1986: 90).

Yet, as the case of the Arab Spring abroad demonstrates, dissidents who travel abroad have the potential to induce change from without. In fact, those who remain loyal to the people and places left behind can use voice after exit to demand change at home (Glasius Reference Glasius2018; Hirschman Reference Hirschman1993; Hoffmann Reference Hoffmann2010; Mueller Reference Mueller1999; Newland Reference Newland2010; Pfaff Reference Pfaff2006; Pfaff and Kim Reference Pfaff and Kim2003). Members of diasporas – a term used here to refer to the exiles, émigrés, expatriates, refugees, and emigrants of different generations who attribute their origins to a common place – do so for many reasons.Footnote 5 Memories of their lives before displacement, connections to grandparents and friends from home, summertime visits to their hometowns, annual picnics and flag-flying parades, religious gatherings and diaspora associations, grief and nostalgia over childhoods spent in the homeland, and foreign business dealings all serve to bind members of national and ethnic groups to a home-country (Guarnizo et al. Reference Guarnizo, Portes and Haller2003; R. Smith Reference Smith2006). So too do experiences of marginalization in the host-country make them feel more at home in their places of origin. Consequently, diaspora members’ “ways of being and ways of belonging” can bind them to the homeland and become transnational in character (Levitt and Glick Schiller Reference Levitt and Glick Schiller2004: 1002), rather than bound within their place of settlement.Footnote 6

History shows that exile has long served as an incubator for diaspora voice. While traumatic for its victims, banishment enables dissidents to survive abroad during periods of repressive crackdown at home (Gualtieri Reference Gualtieri2009; He Reference He2014; Ma Reference Ma1993; Shain Reference Shain2005[1989], Reference Shain2007; Taylor Reference Taylor1989). Many nation-states have been founded by exiles, including China’s Sun Yat-sen, Poland’s Tadeusz Kościuszko, and Vietnam’s Ho Chi Minh. Others have captured revolutions already underway, as when Vladimir Lenin returned by German train to lead the Bolshevik coup d’état in Russia and Ruhollah Khomeini arrived by plane from France to forge the Islamic Republic of Iran. Diaspora members from the Balkans, Ireland, Sri Lanka, and Eritrea have bankrolled wars and funded nation-building projects from afar by channeling cash and matériel to their homelands (Hirt Reference Hirt2014; Hockenos Reference Hockenos2003; Lainer-Vos Reference Lainer-Vos2013; Ma Reference Ma1990; Maney Reference Maney2000). In a world where having a nation-state grants ethnic groups protection (Mann Reference Mann2005), minority movements among Tibetans, Palestinians, Basques, and Kurds have demanded sovereignty and ethno-religious rights in their homelands (Adamson Reference Adamson2019; Bamyeh Reference Bamyeh, Segura and DeWind2014; Baser Reference Baser2015; J. Hess Reference Hess2009). Expatriates with axes to grind, such as anti-communist Cubans and Iraqis opposing Saddam Hussein, have also forged powerful lobbies to challenge home-country governments and shape host-country foreign policy (Ambrosio Reference Ambrosio2002; Mearsheimer and Walt Reference Mearsheimer and Walt2007; T. Smith Reference Smith2000; Vertovec Reference Vertovec2005). In these cases and many others, exiles and diaspora movements have become what Yossi Shain (Reference Shain2005[1989]: xv) describes as “some of the most prominent harbingers of regime change” in the world (see also Field Reference Field1971).

As authoritarianism resurges across the globe today and in the foreseeable future (Repucci Reference Repucci2020), diaspora movements will undoubtedly continue to play a central role in an increasingly urgent fight against dictatorships. But although they have played a notable role in fomenting change in their homelands for centuries, surprisingly little attention has been paid to explaining their interventions. To fill this gap, I address two central questions: When do diaspora movements emerge to contest authoritarianism in their places of origin? How, and under what conditions, do activists fuel rebellions therein? By systematically investigating how revolutions ricocheted from Libya, Syria, and Yemen to the United States and Great Britain, this book provides interesting new answers.

The central contribution of The Arab Spring Abroad is the provision of a set of conditions explaining when, how, and the extent to which diasporas wield voice after exit against authoritarian regimes. In so doing, the book demonstrates that exit neither undermines voice, as Hirschman (Reference Hirschman1970) suggests, nor does it necessarily foster voice, as historical examples of exile mobilization illustrate. Instead, I argue that while some exiles use exit as an opportunity for voice, diaspora members’ ties to an authoritarian home-country are more likely to suppress voice after exit within the wider anti-regime community for at least one of two reasons.

The first is that home-country regimes may actively repress voice in the diaspora using violence and threats. When they do, non-exiles are likely to remain silent in order to protect themselves and their relatives in the home-country. The second reason is that home-country ties can entangle diaspora members in divisive, partisan conflicts rooted in the home-country. When these home-country rifts travel abroad through members’ transnational ties, they can factionalize regime opponents and make anti-regime solidarity practically impossible. I find that these two transnational forces – what I term transnational repression and conflict transmission, respectively – largely deterred anti-regime diaspora members from Libya, Syria, and Yemen from coming out and coming together against authoritarianism before the revolutions in 2011.

This book then demonstrates how and why this situation can change. Specifically, I show how major disruptions to politics-as-usual in the home-country can give rise to voice abroad. As regimes massacred demonstrators, prompted the formation of revolutionary coalitions, and led to major humanitarian crises during the Arab Spring, they induced what sociologist David Snow et al. (Reference Snow, Cress, Downey and Jones1998) call quotidian disruptions to everyday life and regime control. The revolutions therefore not only produced civil insurgencies and wars at home, but also traveled through diaspora members’ ties to produce quotidian disruptions abroad. As I detail further below, as the Arab Spring undermined the efficacy of regimes’ long-distance threats and united previously fragmented groups, outspoken exiles and silent regime opponents decided to come out and come together to wield voice to an unprecedented degree.

At the same time, the final chapters of the book argue that even after diaspora members take up voice in unprecedented ways, they only come to make impactful interventions in anti-authoritarian rebellions if two additive factors come into play. Drawing from the comparative analysis, I show that they must (1) gain the capacity to convert resources to a shared cause, and (2) gain geopolitical support from states and other powerholders in order to become auxiliary forces for anti-authoritarianism. When they do, they can channel cash to their allies, mobilize policymakers, and facilitate humanitarian aid delivery on the front lines. Otherwise, activists may voice their demands on the street, but they will not become empowered to fuel rebellion and relief when their help is needed most. Taken together, by bringing attention to the important, but dynamic and highly contingent, roles that diaspora movements play in contentious politics, this study demonstrates when voice after exit emerges, how it matters, and the conditions giving rise to diaspora movement interventions for rebellion and relief.

Before elaborating these claims, this chapter summarizes the events of the Arab Spring, explains the puzzles that motivated this research, and justifies the comparisons that form the basis of my analysis.

1.1 The Arab Spring Uprisings

The Arab Spring began with a lone spark of discontent on December 17, 2010, when a young Tunisian named Mohammed Bouazizi set himself on fire to protest police harassment. This act of despair galvanized demonstrations, and after a police crackdown, protests escalated into a nationwide rebellion against the twenty-three-year dictatorship of Zine El Abidine Ben Ali. After labor strikes crippled the country and the military refused to shoot into the crowds, Ben Ali and his family fled Tunisia to Saudi Arabia, stunning global audiences on January 14, 2011. Just days later, activists in Egypt followed suit. On January 25, protesters in Cairo broke through police cordons to occupy a central downtown location called Tahrir Square. After setting up an encampment, snipers and thugs attacked the sit-in movement in full view of the international media. Protesters stood their ground in Cairo and beyond, set police stations ablaze, pleaded with the military to defect, and spurred a nationwide labor strike. After failing to quell the protesters with force, Egypt’s pharaoh-president Hosni Mubarak resigned days later, on February 11.

As rumors circulated as to which regime would be next, activists and ordinary people in the region’s poorest country, the Republic of Yemen, came out in force. From the dusty, cobblestoned roads of the capital Sanaʻa to the humidity-soaked lowlands of the south, citizens of one of the world’s most heavily armed nations marched peacefully to demand the resignation of their longtime president, Ali Abdullah Saleh. Vowing to stay on, it did not take long before Saleh unleashed gunmen to clear the streets. The brazen murders of unarmed protesters, including a massacre on March 18, dubbed the Friday of Dignity (Jumaat al-Karamah), led to the defection of military, government, and tribal elites. After pitched battles with loyalists in the summer, Saleh remained dug in – that is, until a bomb planted in the presidential palace sent him to a hospital in Saudi Arabia. Facing pressures at home and sanctions from the United Nations, he eventually signed a deal, brokered by the members of the Gulf Cooperation Council, to step down in November 2011 in exchange for legal immunity.

While Egyptians battled regime loyalists back in February, rumors circulated online that Libya was planning its own “Day of Rage.” The regime of Colonel Muammar al-Gaddafi attempted to preempt protests by arresting a well-known lawyer, Fathi Terbil, in Libya’s eastern city of Benghazi. Instead of preventing protests, however, the arrest of this local hero did the opposite. Benghazians had long suffered at the hand of Gaddafi, who had come to power in 1969, and Terbil’s arrest provoked a riot. As the military in Benghazi defected or fled, protests spread westward all the way to the capital of Tripoli. In response, Gaddafi promised to cleanse the streets of “rats” and “cockroaches” (Bassiouni Reference Bassiouni2013). After the United Nations Security Council approved intervention against his onslaught, a nascent insurgency of military defectors and volunteers became embroiled in a revolutionary war backed by global powers. But intervention by NATO was no guarantee of success. A terrible siege against the port city of Misrata and a stalemate along the Nafusa Mountains dragged on into the summer. In August, however, the forces of the Free Libyan Army (also known as the National Liberation Army) broke the impasse and marched on Tripoli, prompting Gaddafi and his loyalists to flee into the desert. By November, the self-proclaimed “King of Africa” was captured and killed, signifying the end of a forty-two-year- long nightmare.

In February, once-unthinkable forms of public criticism began to emerge in Syria, which had been kept under the thumb of a totalitarian family dynasty for more than forty years. As demonstrators in Damascus were beaten and incarcerated for holding peaceful vigils, protests erupted in outlying cities such as Daraʻa against local corruption and daily indignities. The response of Bashar al-Assad’s regime was murderous, and the imprisonment of children who had scrawled Arab Spring slogans in graffiti only stoked more outrage. While the growing protest movement initially called for reform, repression turned protesters into full-scale revolutionaries. Bashar al-Assad unleashed the full power of the military and loyalists against civilians according to the creed “Bashar, or we burn the country,” and revolutionaries were left with little choice but to defend themselves from being massacred. Facing barrel bombs, Scud missiles, and chemical weapons, entire towns and cities were decimated by Assad and his backers (including Hezbollah, Russia, and Iran) in the following months and years. The ensuing war also enabled foreign extremists, from Ahrar al-Sham to the so-called Islamic State (ISIS), to flood in from Iraq, which Assad used to further justify mass destruction. As hundreds of thousands were killed and millions fled, the violence produced the world’s worst refugee crisis since World War II. Ten years later, pockets of resistance remained active, but the regime’s allies had enabled its survival. However, it should not be forgotten that for a time, the Syrian people had brought it to the brink.

More to the point: In the early days of the Arab Spring in 2011, the fate of these movements was far from certain; as spring turned into summer, people across the world tuned in day and night on their laptops and televisions to watch the uprisings unfold. Stomach-churning reports detailed the exceedingly high price that ordinary people in the region were paying for speaking out. Victims included defenseless youth in Yemen, mowed down by snipers; video footage displayed their lifeless bodies lying side by side, wrapped in white sheets stained with blood. Libya’s most beloved citizen-journalist with a kind smile, Mohammed Nabbous, was shot and killed in March during Gaddafi’s attack on Benghazi. In May, global audiences learned that a thirteen-year-old boy named Hamza al-Khateeb had been tortured to death by Syrian forces for smuggling food to protesters under siege. Nevertheless, the people persisted. Libyans rallied around the slogan “we win or we die” of famed freedom fighter Omar al-Mukhtar, a martyr of the resistance against Italian colonizers. Syrian men carried their children on their shoulders to the city of Homs’s iconic New Clock Tower to chant “al-shaʻab yurid isqat al-nitham!” (the people demand the fall of the regime!). Tens of thousands of Yemeni women and men occupied the highways of Sanaʻa, the sloping streets of Taʻiz, and the lowlands of Aden in the south to demand liberty, bread, and dignity.

Further afield, other movements were crushed or quelled. Bahrain’s sit-in movement in Manama was swiftly suppressed under the weight of Saudi tanks, while protesters in Morocco and Jordan struck a tacit détente with their kings. Meanwhile, the masses in Libya, Syria, and Yemen faced prolonged and bloody standoffs over the course of 2011 and beyond that would forever change the region. It would also have an indelible impact on anti-regime diasporas across the world.

1.2 The Arab Spring Abroad

As the Arab Spring spread across the region, so too did it activate supporters in the Libyan, Syrian, and Yemeni diasporas. Over steaming teacups in a crowded London tea shop, a young professional named Sarah recalled how the Arab Spring marked her entrée into the anti-regime struggle. After Gaddafi’s forces had fired on unarmed protesters in February, she told me, Sarah’s aunt rang her from Benghazi to report that her young cousin had been killed. Sarah was stunned. She had not even been following the news that day, much less anticipating an open revolt that would impact her family so deeply. After a shocked pause, Sarah urged her aunt to stay indoors. But her aunt had refused, declaring, “Sarah, it’s either him or us.” In the words of Omar al-Mukhtar, the time had come to win against their oppressor or die trying. Gunfire rattled in the background as Sarah hung up the phone.

The following day, Sarah continued, she met her Libyan friends at a cafe. Usually, they chatted about work or played squash. Today, clasping their hands around ceramic cups, the mood was sullen. Sarah’s friend finally spoke up. He proposed that they go protest at the Libyan embassy. They agreed, but Sarah was nervous. Despite having attended demonstrations for other causes in the past, she had never done anything political for Libya before. Sarah pulled the hood of her sweatshirt tightly around her face as they waited for a bus to Knightsbridge in central London. Libya’s uprising had just begun and the consequences were uncertain, but it had suddenly become unthinkable to stay at home and do nothing.

For Libyans forced into exile, on the other hand, the Arab Spring was the moment that they had been waiting for their entire lives. Thousands of miles away, in the trimmed suburbs of Los Angeles, a young couple named Hamid and Dina told me their story. Like Sarah, Dina’s activism for regime change was new; Hamid, on the other hand, was a seasoned veteran. His uncles had been killed fighting Gaddafi in the 1980s, and the family had been forced to flee after his birth. This dislocation bonded Hamid to fellow exiles – lifelong friends such as Ahmed and Abdullah, Hibba and M.Footnote 7 – whose hatred of Gaddafi smoldered like a burn on their guts. From these friendships they forged Gaddafi Khalas! (Enough Gaddafi!), an organization dedicated to publicizing the regime’s atrocities and organizing a protest against Gaddafi’s 2009 visit to the United Nations in New York. With regime change looking evermore hopeless by this time, the members of Enough Gaddafi! felt a responsibility to keep the torch of resistance alive. “We had no money and no experience,” Hamid told me, “but we had heart. Besides, who else was going to do the job of reminding the world what a monster Gaddafi really was?” In the years before the revolution, however, their movement was a lonely one. Libyans abroad generally avoided uttering Gaddafi’s name, much less broaching the subject of regime change.

In the early days of 2011, Hamid followed the riotous protests underway in Tunisia and Egypt with a fastidious obsession, staying up nights to watch the rebellions unfold on his computer. Once rumors circulated that Libya was going to have an uprising of its own, the Enough Gaddafi! network was ready. If the Libyan people were brave enough to speak out from behind a thick wall of censorship and isolation, he and his colleagues told me, outsiders needed to take notice. Armed with little more than their laptops, Hamid and his friends transformed instantly into the revolution’s public relations team. They exposed regime violence unfolding beyond the view of the international media, posted recordings of Libyans’ testimonies on Twitter, and documented the death toll in real time. Once at the very fringe of global politics, Hamid and his friends were catapulted overnight into its center by the Arab Spring.

As anti-regime activists like Hamid launched an all-out information war against Gaddafi using the Internet, newcomers like Sarah amassed donations for places like Misrata, a city that became known as Libya’s Stalingrad after relentless shelling by the regime. Dina, who met Hamid over the course of the war, traveled from California to Doha and into Libya’s liberated territory to coordinate media for the revolution’s government-in-waiting. They were joined by many others. Surgeons and students booked tickets to Cairo, driving for hours to volunteer in Libya’s field hospitals, remote battlefields, rebel media centers, and tented refugee camps. Businessmen, bureaucrats, and teachers who had previously given up hope of a future without Gaddafi transformed into lobbyists, imploring outside powers to stop the regime’s slaughter of civilians. From the first hours of Libya’s uprising in February to the fall of Tripoli in August, activists from the diaspora mobilized to lend their labor and their voices to the revolution. Determined not to let their conationals suffer in silence, the anti-regime diaspora joined the struggle in every way imaginable as an auxiliary force against authoritarianism.

Likewise, Syrians in the diaspora intervened for rebellion and relief as the uprising escalated from isolated pockets of resistance to a war that engulfed their homeland. Syrian youth in Chicago and London helped protesters in Damascus to coordinate flash mobs using their MacBooks. White-collar professionals from Arkansas and Florida ushered reporters and politicos, such as US Senator John McCain, into liberated territories while guarded by grim-faced men carrying automatic rifles. Longtime exiles introduced revolutionaries in Syria to US Ambassador Samantha Power at the United Nations and spoke with Jon Stewart on The Daily Show. Volunteers from Bristol and Manchester drove ambulances and delivered trauma kits to hospitals in the liberated province of Idlib. Activists also flooded into Turkey to join the revolutionary government-in-waiting, send aid across the border, and hold trainings on how to document war crimes. Long before pundits claimed that the Syrian revolution was doomed to fail, Syrians at home and abroad joined forces to rebel against iron-fisted totalitarianism and support the victims of Assad’s scorched-earth response.

Yemenis abroad also mobilized to support the thousands of protesters who poured onto the streets over the course of 2011. Self-appointed lobbyists in Washington, DC, and London demanded that world powers and the United Nations force president Saleh to resign. Activists demonstrated outside the Saudi and Yemeni embassies to demand an end to violence against civilians. Activists held photography exhibitions to educate the public about the uprising and organized fundraising banquets for Islamic Relief’s aid work in Yemen. Local leaders also challenged the inertia of their community organizations by demanding that regime sympathizers vacate their posts and make way for new leadership. From her university’s cafeteria in Birmingham, a young organizer named Shaima exalted that the Arab Spring had induced “a revolution in the UK, without a doubt!” by bringing community members together for hope, democracy, and dignity as never before.

1.3 The Role of Diaspora Movements in Contentious Politics

Not all emigrants “keep a foot in two worlds” and retain ties to people and places at home (Levitt Reference Levitt, Jopke and Morowska2003; Levitt and Glick Schiller Reference Levitt and Glick Schiller2004; Waldinger and Fitzgerald Reference Waldinger and Fitzgerald2004). The feeling of belonging to the country of origin, as sociologist Roger Waldinger (Reference Waldinger2015) argues, is subject to fray as later generations become incorporated into their receiving society. Transnational practices may also be “blocked” by home-country conflict and inaccessibility (Huynh and Yiu Reference Huynh, Yiu, Portes and Fernández-Kelly2015). Yet, as Waldinger and other social scientists such as Peggy Levitt and Nina Glick Schiller (Reference Levitt and Glick Schiller2004) have demonstrated, first-, 1.5-,Footnote 8 and second-generation cohorts often retain some meaningful connection to their places of origin, whether through video chats with their relatives or through their self-professed identities (Brinkerhoff Reference Brinkerhoff2009). Equipped with insider knowledge, multilingualism, and a personalized stake in home-country politics, these ties become even more precious when the home-country is insulated from the global media and caged by a repressive regime. Under such circumstances, personalized connections to loved ones at home may be the only way to gather reliable information that circumvents state propaganda and international isolation.

Diaspora members influence homeland affairs by transferring a myriad of resources homeward. Not all diasporas are equally wealthy, but even poor migrants from countries such as Haiti, Tajikistan, and Honduras send millions of dollars homeward every year. In 2017, migrants sent an astounding $613 billion to their home-countries by air, sea, and wire, 76 percent of which went to low- and middle-income countries (World Bank 2018). These remittances vastly outnumber official aid to these countries by a factor of three (Ratha et al. Reference Ratha, De, Kim, Plaza, Seshan and Yameogo2019). Even then, these figures do not account for the millions of dollars that move through informal channels, such as local agents and wire services, to the most remote locales (Horst Reference Horst2008b, Reference Horst, van Naerssen, Spaan and Zoomers2008c; Laakso and Hautaniemi Reference Laakso and Hautaniemi2014; Lyons and Mandaville Reference Lyons and Mandaville2012; Orjuela Reference Orjuela2008).

Remittances tie diaspora members to their homelands by reinforcing a sense of obligation to those left behind (Glick Schiller and Fouron Reference Glick Schiller and Fouron2001). They also grant diasporas a disproportionate influence in home-country politics (Kapur Reference Kapur2010; Lainer-Vos Reference Lainer-Vos2013; Shain Reference Shain2007). While most are used to support family members, remittances are also channeled into public works, charity, and political parties (Bada Reference Bada2014; Duquette-Rury Reference Duquette-Rury2020; Horst Reference Horst2008a, Reference Horst2008b, Reference Horst, van Naerssen, Spaan and Zoomers2008c; Portes and Fernández-Kelly Reference Portes and Fernández-Kelly2015; R. Smith Reference Smith2006). For these reasons, sending-state governments are increasingly wooing their diasporas by granting national members dual citizenship, out-of-country voting rights, and congressional seats, as well as by forming institutions to foment connectivity (Brand Reference Brand2014; Gamlen Reference Gamlen2014; Gamlen et al. Reference Gamlen, Cummings and Vaaler2017; Harpaz Reference Harpaz2019; Ragazzi Reference Ragazzi2017). Their remittances can also make or break the peace by extending the duration of civil wars, funding reconstruction efforts, or both (Adamson Reference Adamson and Checkel2013; Brinkerhoff Reference Brinkerhoff2011; Byman et al. Reference Byman, Chalk, Hoffmann, Rosenau and Brannan2001; Cederman et al. Reference Cederman, Girardin and Gleditsch2009; Collier and Hoeffler Reference Collier and Hoeffler2000; Collier et al. Reference Collier, Elliott, Hegre, Hoeffler, Reynal-Querol and Sambanis2003; Orjuela Reference Orjuela2008; Shain Reference Shain2002; H. Smith and Stares Reference Smith and Stares2007).

Diasporas are further primed to become transnational political players because of their privileged “positionality” (Koinova Reference Koinova2012) vis-à-vis those left behind (Germano Reference Germano2009). Their members often include wealthy, well-educated, and highly skilled activists who go abroad to study at globally ranked universities. Equipped with multilingualism and multiculturalism, “cosmopolitan patriots” (Appiah Reference Appadurai1997) and second-generation youth often literally speak the languages of insiders and outsiders alike (M. Hess and Korf Reference Hess and Korf2014). They send what Levitt (Reference Levitt1998) calls “social remittances” homeward in the form of foreign cultural practices, knowledge, and skills (Wescott and Brinkerhoff Reference Wescott and Brinkerhoff2006). By circulating ideas that promote civil, political, and human rights, these members enact transnational citizenship and diffuse liberal norms (Boccagni et al. Reference Boccagni, Lafleur and Levitt2016; Finn and Momani Reference Finn and Momani2017; Lacroix et al. Reference Lacroix, Levitt and Vari-Lavoisier2016). Phillip Ayoub’s (Reference Ayoub2016: 34) study of Polish activism in Germany from 1990 through the 2000s, for instance, shows that expatriates engage in “norm brokerage” by translating international norms to audiences at home and, in turn, connecting outside supporters with home-country activists. Their positioning between social worlds makes them powerful proponents of liberal change (Brinkerhoff Reference Brinkerhoff2016; McAdam et al. Reference McAdam, Tarrow and Tilly2001). It follows that diaspora activists have access to the rhetoric, tactical adaptations, and strategical savvy to remake the homeland in their image (Shain Reference Shain1999). Researchers also argue that elites are especially primed to become powerful influencers at home (Guarnizo et al. Reference Guarnizo, Portes and Haller2003) because their privileges enable them to participate in public affairs and circulate between two or more worlds.

Diaspora groups who settle in countries that purport to uphold political rights and civil liberties are further advantaged by what social movement scholars call “political opportunities” for transnational action (McAdam et al. Reference McAdam, McCarthy and Zald1996; Meyer Reference Meyer2004; Tarrow Reference Tarrow1998, Reference Tarrow2005). These opportunities include the rights to hold peaceful protests, establish social movement organizations, and lobby for political causes at the domestic and international levels (Bauböck Reference Bauböck2008; Brubaker and Laitin Reference Brubaker and Laitin1998; Cohen Reference Cohen2008; Eccarius-Kelly Reference Eccarius-Kelly2002; Fair Reference Fair, Smith and Stares2007; Orjuela Reference Orjuela2018; Østergaard-Nielsen Reference Østergaard-Nielsen2003; Wayland Reference Wayland2004). Not all diasporas settle in places that protect the right of assembly or the free flow of information, but those who do are especially well-positioned to disseminate their grievances online, in their communities, and through protests (Amarsaringham Reference Amarsaringham2015; Bernal Reference Bernal2014; Betts and Jones Reference Betts and Jones2016; Brinkerhoff Reference Brinkerhoff2005; Quinsaat Reference Quinsaat2019). Exiles find themselves gaining added opportunities for voice when their aims align with the agendas of host-country policymakers (DeWind and Segura Reference DeWind and Segura2014), as in the cases of anti-regime Russians, Cubans, and Iranians in the United States. Iraqi exiles like Ahmad Chalabi, who was on the Central Intelligence Agency’s and State Department’s payroll for decades, became infamous for helping the administration of president George W. Bush justify the occupation of Iraq (Roston Reference Roston2008). In this way, as political scientists Alexander Betts and Will Jones (Reference Betts and Jones2016: 9) argue, outside patronage “animates” diaspora elites and their movements.

Taken together, research on transnational movements, migration, and diasporas illustrate how contentious politics are not contained within the borders of the nation-state. As national groups and belonging become increasingly “unbound” across state borders (Basch et al. Reference Basch, Glick Schiller and Szanton Blanc1994; Harpaz Reference Harpaz2019) and transnational practices become easier and cheaper to undertake (Vertovec Reference Vertovec2004), so too do diaspora actors appear to wield disproportionate influence in homeland affairs. Equipped with the ties, resources, and political opportunities needed to act on their anti-regime grievances, their actions can create a “serious politics that is at the same time radically unaccountable” (Anderson Reference Anderson1998: 78; see also Adamson Reference Adamson and Tirman2004; T. Smith Reference Smith2000). It is for these reasons that scholars such as Benedict Anderson (Reference Anderson1998) and Samuel Huntington (Reference Huntington1997, Reference Huntington2004) have expressed alarm at the ways in which diaspora movements instigate insurgencies and influence policy in pursuit of sectarian self-interests. Such “unencumbered long-distance nationalists,” Anderson (Reference Anderson1998: 78) warns, “well and safely positioned in the First World, … send money and guns, circulate propaganda, and build intercontinental computer information circuits, all of which have incalculable consequences in the zones of their ultimate destinations.” For better and for worse, anti-regime diasporas appear well-poised to wield, in Hirschman’s terminology (Reference Hirschman1970), loyalty and voice after exit as weapons for change at home.

1.4 Emergent Puzzles from the Arab Spring Abroad

Studies of diaspora and emigrant mobilization have advanced our understanding of contentious politics by demonstrating that their transnational practices shape home-country politics, conflicts, and international relations (Adamson Reference Adamson, Biersteker, Spiro, Raffo and Sriram2006). In light of their home-country loyalties and members’ relatively privileged “positionality” abroad (Koinova Reference Koinova2012), it is not especially surprising that diaspora members mobilized to help their compatriots under siege during the Arab Spring. As I set out to investigate this phenomenon by undertaking fieldwork across the United States and Great Britain, I found that Libyans, Syrians, and Yemenis had played up to five major roles in the uprisings. First, they broadcasted information about events on the ground and revolutionaries’ demands to outside audiences through protests, lobbying, and by publicizing information. Second, they represented the revolution to their host-country governments and the media, whether formally or informally, and served in its various organizations and governments-in-waiting. Third, they brokered for the rebellions and relief efforts by connecting their allies on the ground with outsiders in politics, the media, and civil society. Fourth, they remitted their skills, material aid, and cash to the cause. Lastly, they volunteered in the home-country and immediately outside its borders to help their conationals in every way imaginable. While my interviewees firmly asserted that revolutionaries at home were the real heroes, they nevertheless became a collective transnational auxiliary force against authoritarian regimes in 2011 and beyond.

Yet, much of what I learned and observed about diaspora mobilization over the course of my research was downright puzzling – and not only to me, but to many of my respondents as well. For instance, beginning in the fall of 2011, I witnessed hundreds of Syrian Americans come out to support the revolution by demonstrating on the streets of Southern California. During these events, participants raised their voices to demand dignity and freedom for Syria through chants, public appeals, and in song. However, their efforts to engage in what social scientists call public, collective claims-making (Koopmans and Statham Reference Koopmans and Statham1999; McAdam et al. Reference McAdam, Tarrow and Tilly2001) by criticizing the Assad regime and demanding international support also had a protective, private quality to it. On the street corners of Anaheim, for instance, demonstrators often hid their faces behind scarves and sunglasses. At a community meeting hosted by the Syrian American Council of Los Angeles in December 2011, I was explicitly instructed not to photograph the audience even though an organizer declared that “the wall of fear has been broken!” Even more confusingly, some activists showed their faces in their communities, but not online; others created pro-revolution Facebook pages, but then quickly made them secret or closed groups. And until I became a familiar face, my presence at protests was also viewed with suspicion. As I observed, the Syrian community was coming out on the streets in greater numbers each week to condemn the Assad regime. However, despite being thousands of miles from the front lines, many seemed deeply reluctant to lend their faces and names to the cause, sometimes even month or years after the revolt’s inception.

I was also perplexed by the content of my conversations with Yemeni activists, which often went on for hours over steaming bowls of ful, a delicious bean stew that bubbled in blackened bowls, and rice heaping with a traditional salsa-like condiment called sahawag. During these extended interviews, I learned that anti-regime mobilization was a deeply unifying and fragmenting experience for Yemenis in the diaspora. For instance, from a Yemeni cafe in Birmingham, England, a beaming man named Ali in dark-rimmed glasses described how the Arab Spring had made him feel marginalized and maligned in his own community. Ali described how his writings about the Yemeni revolution were being criticized and censored by his conationals on Facebook, how he and his friends had been shut out of protests, and how hurt they felt by others’ efforts to shut them up. Ali had been a longtime supporter of change in Yemen, but as a result of these experiences, he had withdrawn his support shortly after the uprising began. Many other Yemenis echoed a version of his story.

Syrian activists were also deeply divided, and often preoccupied with perceived power grabs and accusations of co-optation in their movements abroad. The transcripts of our conversations read as venting sessions against other like-minded activists and movements within the opposition who, as several British respondents put it, spent as much time “slagging each other off” as actually helping their compatriots at home. As a result, many of the most ardent anti-regime exiles and community figures ended up withdrawing their support for the revolution as time wore on. I also learned that diaspora activists’ actual interventions in the rebellions and for badly needed humanitarian relief varied considerably. Syrians in Britain, for instance, reported numerous obstacles to supporting the Arab Spring, from the costs of continuously volunteering their time and labor to being left out of the policymaking process. Syrians in the United States, while certainly reporting fatigue and burnout, instead forged a robust set of advocacy and relief organizations and continued lobbying over the course of the revolution and subsequent war.

Furthermore, although Yemenis hailed the Arab Spring as a turning point in their communities, they also detailed their incapacity to help revolutionaries in a tangible way. As Yemen’s dissidents were gunned down in city squares and field hospitals were overrun with casualties in 2011, organizers like Shaima found their activist groups unable to do much more than voice their solidarity on the streets from a distance. Shaima and I spent hours together on buses and sipping teas in Birmingham’s Bull Ring discussing this paradox. “Here, we’re educated,” she mused. “We have activist resources …. Even if you’re not educated to a certain level, there’s opportunities here. It’s about just being able to pick it up and move it. But how do you do that?” Others across the United States and Britain echoed her befuddlement. The Arab Spring was a remarkable time for the anti-regime diaspora, signifying a new phase in community empowerment and collective action. But activists like Shaima had wanted to do more. As I scrawled notes on planes, trains, and at protest events, so too were my jottings filled with question marks.

The emergence of activism for the Arab Spring abroad clearly illustrates how diaspora movements can matter. Yet, four years of fieldwork on Arab Spring-inspired mobilization left me with a series of questions that needed answering. Why did so few diaspora members openly criticize home-country regimes, as Libyan American Hamid’s Enough Gaddafi! network had done, before 2011? Why did it take so long for many of them, especially in the Syrian community, to declare their allegiance to the Arab Spring openly in public? Why did many longtime anti-regime activists withdraw their support for the revolutions in Syria and Yemen? And why did many more conclude that their mobilization potential remained unfulfilled, despite an unprecedented showing of support in 2011?

The more I immersed myself in the existing literature to find answers, the broader my questions became. In the parlance of social movement scholars, why would anti-regime diaspora members with political opportunities, resources, and network ties strategically refrain from speaking out against regimes? Why would collective action fragment and die off during a period of acute conflict and need in the home-country? Why do only some diaspora movements with significant privileges vis-à-vis their home-country counterparts succeed in fulfilling their goals? With the potential of transnational activism to make or break the peace at home, inattention to these questions is a serious lacuna. By investigating how these uprisings reached from the global periphery to diaspora communities at the world’s “center,” this book provides some interesting new insights. The next section elaborates why a comparison of Libyan, Syrian, and Yemeni diaspora activism for the Arab Spring from the United States and Britain provides a useful set of answers. Following this, this book presents a new framework for explaining voice after exit against authoritarian regimes.

1.5 Investigating Libyan, Syrian, and Yemeni Activism from the United States and Britain

It is sometimes hard to recall what the uprisings meant to those of us who watched them unfold on our screens in real time. I began graduate school just a few months prior to the uprisings with a plan to study social movements in the Middle East. Having spent time in Yemen, studying and volunteering for a local rights organization, I was intrigued by how social movements managed to exist at all, much less pursue human rights, in authoritarian contexts. To some, my topic came off as a curiosity. Responses by US-focused scholars along the lines of “are there social movements in the Middle East?” were not uncommon. These reactions changed after the Arab Spring uprisings emerged and inspired the Occupy Wall Street movement, which diffused from New York all the way to Tel Aviv. All of a sudden, my generation was witnessing a global outpouring of rage against authoritarianism and economic austerity on a scale that we had never before witnessed in person.

As the revolutions dethroned dictatorships and shut down city streets, my plans to return to Yemen were undone by the revolution itself. My detour to Jordan that summer was productive, but I felt as if I was missing all the action. Upon returning home to California that fall, however, I discovered that the Arab Spring had emigrated practically to my backyard. Protest movements in support of the uprisings had been popping up in places such as Mile Square Park near my apartment in Orange County, California, to Dearborn, New York, Liverpool, and London, and I wanted to learn more about them. My spouse and I, along with several friends, had co-founded a small nonprofit organization called The Yemen Peace Project in 2010. While we initially worked to criticize the devastating impacts of US drone warfare in the country and to celebrate Yemeni filmmaking and art, many Yemenis became aware of our organization because of our director’s tireless work on social media during the 2011 revolution. By the fall of 2011, when I sent inquiries to our Yemeni contacts asking for information about diaspora activism, many responded by inviting me to learn about their work in concentrated communities such as those in Brooklyn, Liverpool, and Birmingham.Footnote 9 After doing fieldwork across different cities and spending countless hours in Yemenis’ homes, cafes, and in their community associations in 2012, I conducted a total of ninety-two interviews with Yemenis (and one non-Yemeni stakeholder) who had participated in activism for the Yemeni Arab Spring.

While I had refined my questions and learned a great deal during this trip, I had still returned home with more questions than answers. As a result, I made the decision to expand my comparison to include Syrian and Libyan mobilization in the United States and Britain for several reasons. First, while few Yemenis called Southern California home, the region was inhabited by a notable number of Libyans and Syrians who mobilized in response to the Arab Spring as well. Thanks to the kind reception I received from organizers, I joined social media groups and listservs advertising local awareness-raising events, fundraisers, and demonstrations for Libya and Syria. While attending community picnics, fundraising banquets, protests, and awareness-raising forums, their testimonies raised additional questions about diaspora mobilization. Furthermore, because the Syrian revolution was still unfolding over the course of 2011 and 2012, this gave me an opportunity to see how the Arab Spring was impacting mobilization efforts in real time.

But given the fact that the Arab Spring also occurred in other countries such as Tunisia, Egypt, and Bahrain in 2011, why compare diaspora movements from Syria, Libya, and Yemen? Examining the anti-regime activism of these groups in the United States and Britain made sense on other grounds beyond my newfound access to community events. Out of the six MENA countries that gave rise to revolutionary movements during the Arab Spring,Footnote 10 all had been ruled by authoritarian regimes for decades prior to the Arab Spring; undoubtedly, diaspora members from all of these countries were moved by the revolutions.Footnote 11 However, only Libya, Syria, and Yemen produced initial struggles to upend dictatorships that were sustained over the course of months or longer. For Libyans, this occurred from the uprising’s emergence in February to August 2011 when Gaddafi was overrun; the Syrian uprising began in February 2011 and continues at the time of this writing; for Yemenis, the revolution emerged in January 2011 and continued until Saleh agreed to step down that November. In contrast, Tunisia, Egypt, and Bahrain’s initial uprisings averaged approximately one month each in duration.

This is not to say that the revolutions were identical in duration or character – far from it.Footnote 12 As I elaborate in the chapters to come, variation in the uprisings had important impacts on diaspora activism. Nevertheless, the Libyan, Syrian, and Yemeni rebellions took place in contexts that were highly repressive and resource-poor, and they required outside assistance, including international publicity, political leverage, and humanitarian aid, to survive. As a result, each revolution was prolonged enough to give diaspora members the opportunity to forge popular movements intent on intervening on behalf of rebellion and relief.

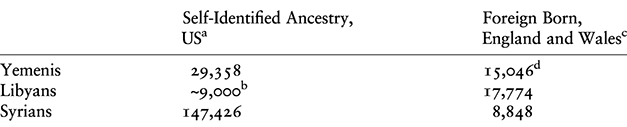

The US-Britain comparison was useful for several reasons as well. First, these two host-countries contained many of the most consequential diaspora communities from Libya, Syria, and Yemen in 2011. Britain hosted the largest community of Libyans outside of their home-country in the city of Manchester at this time due to chain migration and state-sponsored scholarships to its universities. Both host-countries granted refuge to many prominent anti-Gaddafi figures owing to their opposition to his international acts of terrorism in the 1980s and 1990s. Syrians are the oldest and one of the largest Arab immigrant communities in the United States, home to many upper- and middle-class professionals. Syrians in Britain are a smaller community in size (see Table 1.1) but nevertheless home to students and professionals, as well as refugees persecuted by the Assad regime. Yemenis were Britain’s “first Muslims” (Halliday Reference Halliday2010[1992]) owing to South Yemen’s colonial ties with Britain and their employment on British coal ships. Outside of Saudi Arabia and the UAE, Yemenis in the United States and Britain send more remittances homeward than from any other country. Taken together, on the eve of the Arab Spring, each group had significant numbers of first- and 1.5-generation residents in the United States and Britain.Footnote 13

Table 1.1. Estimated number of persons identified as Libyan, Syrian, and Yemeni in the host-country

| Self-Identified Ancestry, USa | Foreign Born, England and Walesc | |

| Yemenis | 29,358 | 15,046d |

| Libyans | ~9,000b | 17,774 |

| Syrians | 147,426 | 8,848 |

a Data from the 2010 American Community Survey, country of ancestry. These figures are the combined totals of persons who listed Yemeni or Syrian as a first or second entry.

b This figure was quoted to me by an advocate for the Libyan American community, but a survey-derived estimate is unavailable. The ancestry data for the 2000 census and the 2010 American Community Survey contain no data on the Libyan-American population.Footnote 14

c Data from the 2011 Ethnic Group census for England and Wales, Office of National Statistics (www.nomisweb.co.uk/census/2011/QS211EW/view/2092957703?rows=cell&cols=rural_urban).

d The BBC writes that there are “an estimated 70–80,000 Yemenis living in Britain, who form the longest-established Muslim group in Britain” but does not cite a source for these figures (www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/islam/history/uk_1.shtml).

Furthermore, the United States and Britain are geopolitical powerholders with permanent positions on the UN Security Council. Their international influence grants anti-regime diasporas political opportunities to lobby policymakers in London and Washington, DC, and at the United Nations headquarters in New York, on matters of the homeland. Both are wealthy democratic states that attract emigrants by virtue of their opportunities for political freedom and social mobility, real and perceived. At the same time, each has subjected groups from the MENA region to discriminatory and Islamophobic policies, immigrant quotas and refugee bans, and rhetoric that paints their members as threats to national (read: white, Anglo-Christian) culture, security, and interests for over a century.Footnote 15 The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, led policymakers in both the United States and Britain to instigate a global war on terror that turned inward, increasing community-wide profiling, surveillance, detention, and deportation of Arabs and Muslims (Brighton Reference Brighton2007). Because these host-countries provide similar “contexts of reception” for Middle Easterners (Bloemraad Reference Bloemraad2006), they provide contextual similarities that can help clarify why diaspora mobilization varies in substantive ways for the same national group across host-countries.

I was able to conduct interviews with Yemeni and Libyan activists after their heads of state had been deposed and the revolutionary movements ostensibly ended in 2012 and 2013, respectively. I conducted a total of sixty-eight interviews for the Libyan case during the post-Gaddafi transition period, which led me to Tripoli in pursuit of the repatriated. I had hoped to do the same with Syrian activists, but the uprising in Syria never reached the same stage. After conducting fieldwork with this community since 2011, I made the strategic decision to conduct interviews in 2014, seventy-nine in total, as the uprising turned into a multisided internationalized civil war and produced a major humanitarian disaster. Despite this variation in timing,Footnote 16 this research design enabled me to compare how diaspora mobilization had emerged and changed within and across groups over time.

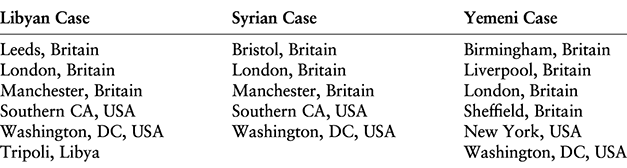

In total, I conducted 239 in-depth interviews among the diaspora communities listed in Table 1.2.Footnote 17 Our extended conversations addressed their migration histories and activist backgrounds, their involvement in social movements before and during the Arab Spring, and perceived failures and successes of their collective efforts. In all, their ranks represented a total of sixty-one groups and organizations, both formal and informal, spread across the United States and Britain.Footnote 18 Activists working for relief warranted inclusion because their home-country regimes viewed independent humanitarian work as traitorous. In fact, those working to deliver charity to the needy incurred as much risk as freedom fighters themselves, as numerous aid workers disappeared into prisons and have been subjected to bombings, torture, and state-sanctioned murder. Many activists engaged in both overtly political and humanitarian work, or switched from one to the other when political work became too fractious.

Table 1.2. Metropolitan areas visited for data collection

| Libyan Case | Syrian Case | Yemeni Case |

|---|---|---|

| Leeds, Britain | Bristol, Britain | Birmingham, Britain |

| London, Britain | London, Britain | Liverpool, Britain |

| Manchester, Britain | Manchester, Britain | London, Britain |

| Southern CA, USA | Southern CA, USA | Sheffield, Britain |

| Washington, DC, USA | Washington, DC, USA | New York, USA |

| Tripoli, Libya | Washington, DC, USA |

Because my resources did not allow me to visit every interviewee in person, I relied on media like Skype and Viber to reach participants in Cardiff, Wales, and Bradford, England; those who were working at the time in Turkey and Qatar; and those who were residing across Michigan (Dearborn, Flint, and Ann Arbor) and in Boston, Chicago, Austin, Houston, Miami, and the San Francisco Bay area. I conducted all interviews in English, though respondents and I frequently used Arabic terms, and no interviewees were excluded from the study on the basis of language. Activists’ abilities in English and Arabic varied, though many were proficient in both.

Finally, I undertook ethnographic observations (and sometimes participant observations) of thirty events related to the revolutions and relief efforts from 2011 until 2014. Most of these events took place with Syrian activists in the Greater Los Angeles area where I was studying and living at the time, though they frequently brought together a range of Arab Spring supporters from different national communities (For readers interested in the analytical approaches and strategies used for verifying and triangulating the data, please see the Methodological Appendix).

In all, what began as a curiosity about diaspora activism led to fieldwork spanning several years and three continents. Thanks to the generosity of my respondents, it produced hundreds of conversations, over three hundred hours of voice recordings, and about two thousand single-spaced pages of transcripts and field notes. These data were analyzed to answer two questions: When do diaspora members engage in public, collective claims-making against authoritarian regimes? How and why do their mobilizations vary over time?

1.6 The Conditions Shaping Voice After Exit

In answering these questions, the book’s central contribution is the provision of a set of conditions explaining when, how, and to what extent diasporas wield voice against authoritarian regimes. My argument, in brief, is that when home-country ties subject diaspora members to regime threats and violence (transnational repression) and divisive political disputes (conflict transmission), anti-regime voice will be weak. When quotidian disruptions at home upend these transnational deterrents abroad, diaspora members become empowered to capitalize on host-country political opportunities and express voice against regimes in word and deed. However, the extent to which they then intervene on behalf of rebellion and relief will be mitigated by two additional additive forces – that of resource conversion and geopolitical support by states and other international powerholders. When either or both of these forces are lacking, activists may be free to voice their claims on the street, but diaspora mobilization will do little to fuel rebellions and help their allies at home.

The theoretical framework is detailed in Chapter 1. This chapter grounds my arguments in existing research and elaborates how the book’s theoretical contributions advance our understanding of transnational activism and voice-after-exit among diasporas. Readers uninterested in theory may choose to skip directly to Chapter 2, which describes how the rise of authoritarian-nationalist regimes in Libya, Syria, and Yemen in the 1960s and 1970s pushed emigrants abroad. Owing to the additional “pull” factors of host-countries with democratic freedoms and educational opportunities, the United States and Britain came to host a range of anti-regime members, exiles, and well-resourced professionals with the requisite grievances to form opposition movements abroad. First- and second-generation regime opponents also retained ties to their home-countries in the form of familial connections, experiences and memories, self-professed identities, and – for those not in exile – regular trips to visit the home-country. Nevertheless, anti-regime movements were small, atomized, and considered partisan by their conationals before the Arab Spring. Neither Libyan and Syrian exiles nor well-resourced white-collar professionals were able to forge public member-based associations or initiate mass protest events until well into the Arab Spring. Yemeni movements, meanwhile, focused on supporting southern separation from the Yemeni state, rather than on the reform or liberalization of the central government.

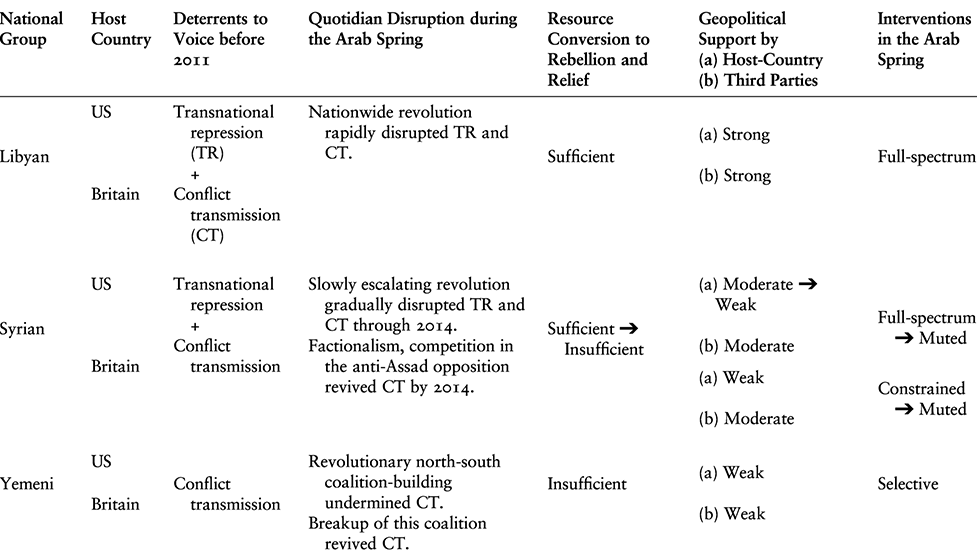

Chapter 3 then demonstrates why this was the case, illustrating how two transnational social forces depressed and deterred anti-regime mobilization before the Arab Spring. They did so by embedding diaspora members in authoritarian systems of state control and sociopolitical antagonisms through individuals’ home-country ties. As the third column in Table 1.3 describes, each of these transnational forces was sufficient to suppress diaspora mobilization, but they often operated conjointly before the Arab Spring.

Table 1.3. Summary of findings

| National Group | Host Country | Deterrents to Voice before 2011 | Quotidian Disruption during the Arab Spring | Resource Conversion to Rebellion and Relief | Geopolitical Support by (a) Host-Country (b) Third Parties | Interventions in the Arab Spring |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Libyan | US | Transnational repression (TR) + Conflict transmission (CT) | Nationwide revolution rapidly disrupted TR and CT. | Sufficient | (a) Strong (b) Strong | Full-spectrum |

| Britain | ||||||

| Syrian | US | Transnational repression + Conflict transmission | Slowly escalating revolution gradually disrupted TR and CT through 2014. Factionalism, competition in the anti-Assad opposition revived CT by 2014. | Sufficient ➔ Insufficient | (a) Moderate ➔ Weak (b) Moderate | Full-spectrum ➔ Muted |

| Britain | (a) Weak (b) Moderate | Constrained ➔ Muted | ||||

| Yemeni | US | Conflict transmission | Revolutionary north-south coalition-building undermined CT. Breakup of this coalition revived CT. | Insufficient | (a) Weak (b) Weak | Selective |

| Britain |

The first mechanism, which I call transnational repression, refers to how regimes exert authoritarian forms of control and repress dissent in their diasporas. Regime agents and loyalists from Libya and Syria in particular did so in numerous ways, including by surveilling nationals living abroad, making threats against them, and by punishing regime critics and their family members in the homeland. I find that transnational repression by the Libyan and Syrian regimes made most non-exiles far too mistrustful and fearful to join the exiles who dared to speak out against the regimes before the Arab Spring. As Chapter 3 details, decades of transnational repression among these groups, which included the assassinations of Libyans in London in the 1980s and 1990s and the surveillance of Syrians as far afield as California, deterred the diaspora’s collective ability to speak out and organize against their tormentors. Plagued by widespread suspicion and paralyzing fears of conationals, neither diaspora produced a public membership-based anti-regime association or mass protest in the United States or Britain before 2011. The Yemeni regime, in contrast, attempted to repress its diaspora, but did not have the capacity to silence anti-regime members to the same degree due to its relatively weak governance at home and abroad.

The second mechanism that deterred diaspora mobilization before the Arab Spring is what I call conflict transmission, which refers to the ways in which political conflicts and identity-based divisions travel from the home-country through members’ ties to the diaspora. I find that conflict transmission divided anti-regime diasporas and undermined their mobilization before the 2011 revolutionary wave in several ways. Cleavages among Libyan regime opponents stemmed primarily from the Gaddafi regime’s efforts to rehabilitate itself in the 2000s, which divided hardline regime opponents from reformers. For Syrians, competition and mistrust between anti-regime groups, including between Syrian Kurds, secular liberals, and various factions of the Muslim Brotherhood, reproduced destructive fissures among anti-regime members before the uprisings. For Yemenis, the resurgence of a southern secessionist movement in Yemen around 2007 pitted southern separatists against pro-unity northerners at home and abroad by tying anti-regime activism to Yemen’s fate as a unified republic. This conflict transmission led to avoidance of politics, censorship, and fights over communal resources in Yemeni communities on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. In each case, the transmission of home-country conflicts to the diaspora inhibited the capacity of conationals to work collectively for regime change before 2011.

Given the deterrent effects of transnational repression and conflict transmission, what brought Libyans, Syrians, and Yemenis together for the Arab Spring? Chapter 4 describes how the Arab Spring mobilized members of the anti-regime diaspora not only by stirring grievances and inducing new hopes for change at home, but by disrupting the normative operation and effects of transnational repression and conflict transmission in the diaspora. The Arab Spring induced what David Snow and his collaborators (Reference Snow, Cress, Downey and Jones1998) call a “quotidian disruption” abroad for several reasons. First, the Arab Spring upended the silence-inducing effects of transnational repression in the diaspora as regime repression engulfed members’ loved ones at home. After members’ relatives were killed, detained, and forced to fight or flee, diaspora members felt released from the obligation to keep quiet in order to protect their loved ones from the threat of repression – what I call “proxy punishment” – in Libya and Syria. Activists also decided to come out publicly for the uprisings when they perceived that the home-country regime’s use of repression escalated into collective, arbitrary violence. To them, this escalation signified that going public no longer posed additional risks to their significant others, thus transforming public activism from a high-risk activity into a low-risk one.

The risks and sacrifices undertaken by vanguard activists – such as Hamza al-Khateeb, the Syrian boy who was tortured to death by regime forces for smuggling food to protesters under siege in early 2011 – also led respondents to come out against the regimes in public for moral reasons. Such incidents broadened diaspora members’ sense of moral obligation from their immediate families to the national community as a whole. Diaspora members also went public when they perceived that the regimes were unable to deliver on the threat of transnational repression. After witnessing the defections of students and officials abroad, Libyans felt empowered to come out in public. Furthermore, by 2012, some Syrian respondents came to believe that the regime was too consumed by war at home to sanction them individually. Perceived changes in the regimes’ capacities for repression, therefore, rendered high-risk activism as low-risk (McAdam Reference McAdam1986) and signaled openings in activists’ opportunities for dissent (McAdam Reference McAdam1999[1982]; Tarrow Reference Tarrow2005).

The Arab Spring likewise disrupted the deterrent effects of conflict transmission by rallying anti-regime diaspora members around a common enemy. Anti-regime Libyans abroad experienced a relatively high degree of cohesion as rebels at home launched a zero-sum war against Gaddafi. By uniting these individuals around the slogan “the regime must go,” boundaries within diaspora groups were reconfigured (Wimmer Reference Wimmer2013) and organizers gained the capacity to instigate mass protests.

At the same time, as Table 1.3 summarizes in the column on Quotidian Disruptions, the Arab Spring’s effects on public mobilization and anti-regime solidarity did not unfold at the same pace or endure equally across national groups. While Libyans in the United States and Britain came out rapidly as regime control at home and abroad collapsed, the Syrian revolution emerged gradually. Accordingly, the pace at which activists went public abroad in both host-countries was staggered because regime agents and loyalists continued to threaten and sanction activists abroad during the revolution’s first year. The continuous threats posed by transnational repression led some activists to engage in what I call “guarded advocacy” by covering their faces during protests, posting anonymously online or not at all, and refusing invitations to speak to the media. It was only late in 2012 when most of the Syrians I interviewed made the decision to “come out,” but many knew of others who had not yet, and never would.

The quotidian disruption of conflict transmission also changed over time. Syrian unity across their places of residence splintered as the revolution at home became more internally divided, competitive, and morally compromised. Likewise, once southern Yemenis split from the revolution a few months into the uprising at home, so too did most South Yemeni activists in the diaspora follow suit. The resurgence of conflict transmission from the Arab Spring itself, therefore, undermined the abilities of Syrian and Yemeni organizers to express unified claims to outsiders and led to personalized conflicts, withdrawals, and a shift away from overtly politicized activism among many participants.

After explaining the initial emergence of diaspora movements for the Arab Spring, Chapter 5 then describes differences in activists’ collective interventions for rebellion and relief. As summarized in the far-right column of Table 1.3, the analysis finds that Libyan activists and their movements across the United States and Britain performed what I call a full-spectrum role in the revolutions by undertaking five major strategies for the revolution’s duration. First, they broadcasted their allies’ claims to outside audiences through the Internet, protests, and awareness-raising events in person and online. Second, they represented the cause by joining the revolution’s cadre and media teams, and by lobbying on its behalf. Third, they brokered between parties to the conflict, including between revolutionaries, the media, and policymakers. Fourth, they remitted resources homeward, from their expertise and skills to cash and medical supplies. Fifth, they volunteered on the ground, venturing home to deliver aid, perform surgeries, become interpreters, assist refugees, and even fight with groups known as the Free Libya Army.

In contrast, the responses of the Syrian anti-regime diaspora varied by host-country and over time. While Syrian American movements initially played a full-spectrum role along with their Libyan counterparts, activists in Britain were significantly constrained in attempting to broker for and represent the revolution. Eventually, both movements were muted by the time I conducted interviews in 2014. Yemenis in both the United States and Britain, on the other hand, played a far more selective role in the Arab Spring than either the Libyan or Syrian groups, focusing primarily on broadcasting the aims of the independent youth-led movement and representing the cause to policymakers. Activists recognized that the anti-regime diaspora needed to do more to help their compatriots; yet, most felt blocked from doing more than expressing their solidarity in symbolic ways, such as by holding demonstrations.

The final chapters explain this variation, arguing how two mechanisms shown in the remaining columns of Table 1.3 – resource conversion and geopolitical support – transformed some, but not all, diaspora movements into auxiliaries for the Arab Spring. Chapter 6 demonstrates how the varied conversion of diaspora resources to the cause – their home-country network ties, social capital, and fungible resources – mitigated their movements’ interventions. Libyans’ resources in the United States and Britain were sufficient to address their allies’ needs over time, and Syrians initially had sufficient resources to do the same. However, overwhelming regime repression and growing unease with a fractious rebellion damaged activist-beneficiary networks as the revolution wore on. Furthermore, as Syria’s humanitarian crisis escalated, diaspora resources were drained or diverted from the anti-regime cause. As a result, Syrians’ collective roles in the Arab Spring were drastically reduced.

While Yemen’s largely peaceful revolution did not require the full range of resources needed by Libyans and Syrians entangled in zero-sum wars, activists’ abilities to channel support homeward were hindered by insufficient network ties to protest encampments. This made resource transfers dependent on the existence of personal connections, which were sparse across their movements. Yemenis’ abilities to launch and sustain protest movements also suffered over time as participants’ resources were exhausted. Yemenis in the diaspora poured an exhaustive amount of labor and resources into the effort, but their resources were insufficient to turn them into transnational auxiliaries for the Arab Spring.

Chapter 7 shows how diaspora activists’ interventions were also shaped by the degree of geopolitical support that their allies at home received from their host-country governments and influential third parties, including states bordering the home-country, international institutions, and the media. Support for the Libyan cause was high and consistent as foreign powers, the international media, and relief agencies intervened on behalf of the revolution. Strong geopolitical support gave activists opportunities to broker between parties, represent the revolution to outsiders, and remit their labor, cash, and material aid to the front lines. Support for the Syrian cause, on the other hand, varied between US and British governments. This difference gave Syrian Americans an elevated role to play as brokers and representatives, while Syrians in Britain were largely shut out of policymaking.Footnote 19 Once geopolitical support for the anti-Assad effort waned across the board by 2014, however, most activists’ roles in policymaking were muted in both host-countries. Finally, geopolitical support for the Yemeni revolution was weak in light of Western powers’ backing of an agreement drawn up by members of the Gulf Cooperation Council to supposedly stabilize Yemen (which backfired spectacularly). As a result, Yemenis in the United States and Britain were invited to meetings, but not incorporated into policymaking. This left them hopeful but frustrated with their inability to do more for their compatriots.

1.7 Conclusion

By bringing attention to the conditions that shape diaspora mobilization over time, this study adds an important chapter to a growing literature on revolutions and the Arab Spring. While much work focuses on the dynamics of contention that unfold within nations, revolutions are not contained events within national territories. Instead, mass revolts against regimes are fundamentally “transboundary” phenomena, as George Lawson describes (Reference Lawson2019), that send shock waves across oceans, galvanize extra-national forces, and mobilize activists across borders (Beck Reference Beck2014; Bell Reference Bell, Keohane and Nye1972; Berberian Reference Berberian2019). Diaspora participation in the Arab Spring did not, by itself, determine whether the revolutions would win or lose. But given activists’ roles as the revolutions’ publicists, lobbyists, funders, rescue workers, and fighters, explaining diaspora mobilization is essential for understanding one of the most consequential protest waves in modern history, as well as for explaining how contentious events unfold more generally (Abdelrahman Reference Abdelrahman2011; Adamson Reference Adamson2016; Beaugrand and Geisser Reference Beaugrand and Geisser2016; Seddon Reference Seddon2014).