Book contents

- The Atrocity of Hunger

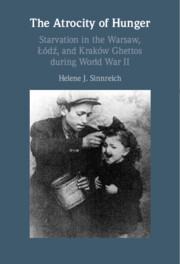

- The Atrocity of Hunger

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 The Nazi Invasion

- 2 Jewish Leadership

- 3 The Supply and Distribution of Food

- 4 The Physical, Mental, and Social Effects of Hunger

- 5 Hunger and Everyday Life in the Ghetto

- 6 Socioeconomic Status and Food Access

- 7 Relief Systems and Charity

- 8 Illicit Food Access

- 9 Labor and Food in the Ghettos

- 10 Deportations and the End of the Ghettos

- Conclusion

- Appendix: List of Kitchens and Food Distribution Sites in the Warsaw Ghetto

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 09 February 2023

- The Atrocity of Hunger

- The Atrocity of Hunger

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 The Nazi Invasion

- 2 Jewish Leadership

- 3 The Supply and Distribution of Food

- 4 The Physical, Mental, and Social Effects of Hunger

- 5 Hunger and Everyday Life in the Ghetto

- 6 Socioeconomic Status and Food Access

- 7 Relief Systems and Charity

- 8 Illicit Food Access

- 9 Labor and Food in the Ghettos

- 10 Deportations and the End of the Ghettos

- Conclusion

- Appendix: List of Kitchens and Food Distribution Sites in the Warsaw Ghetto

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Atrocity of HungerStarvation in the Warsaw, Lodz, and Krakow Ghettos during World War II, pp. 268 - 280Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2023

- Creative Commons

- This content is Open Access and distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/cclicenses/