2 Ballet at the Opéra and La Fête chez Thérèse

History has not looked kindly on the Paris Opéra’s early twentieth-century ballets. Of the thirteen works created between 1900 and 1914, when the Opéra closed temporarily (until December the following year), only one has entered even the periphery of the repertory; none has been commercially recorded.The works staged between 1909 and 1914 have fared worst. Eclipsed on arrival by the productions of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, these ballets have long been overlooked by scholars, the majority of whom have maintained a steady focus on the Russian company. Indeed, with the exception of Lynn Garafola’s monograph on Diaghilev’s troupe, which draws informed comparisons between Russian and French balletic practice, scholarly reference to the Opéra’s pre-war ballets is limited to the institutional histories of Léandre Vaillat, Olivier Merlin and Ivor Guest.1 As a result of their perceived subsidiary status, the ballets La Fête chez Thérèse, España, La Roussalka, Les Bacchantes, Suite de danses, Philotis and Hansli le bossu exist only as visual and textual traces: design sketches, posed photographs, librettos, musical scores, press reviews and other anecdotal testimony lying dormant in the Bibliothèque-musée de l’Opéra, Paris.

I should like to attempt an awakening of sorts here. My aim, at least at the outset of this chapter, is to offer a sense of what pre-war ballet at the Opéra was like, from its visuals and structure to the interaction of music and drama. The surviving materials may also offer clues to the Opéra’s aesthetic impulse, suggesting the extent to which the institution sought to respond to its contemporary situation. This final point is a serious one, given the volume and intensity of press calls, issuing from the early 1900s, for the development of a national ballet. As critics recalled, since the celebrated ‘Romantic’ decades of the 1830s and 40s, ballet at the Opéra – the hothouse of ballet Romanticism – had fallen into decline. Owing in part to the increasing ‘feminization’ of ballet as a social and artistic practice, and to the increasing emphasis on technique, ballet was downgraded to second-class status, to the rank of simple divertissement designed to showcase the resident danseuses étoiles.2 (These étoiles – several of whom came from the Scuola di Ballo of La Scala in Milan – tended to flaunt their brilliant virtuosity at the expense of dramatic expression.) Adding to ballet’s misfortune were three unfortunate cases of combustion. In 1862 the tulle skirt of the up-and-coming Emma Livry caught fire from a stage gaslight and consumed the dancer in flames; in 1894 a fire at a warehouse on Rue Richer destroyed the sets and costumes of all but two ballets in the Opéra’s repertory; this was merely twenty-one years after the fire on Rue Le Peletier, which burnt the theatre to the ground, along with much of its production material.

With an impoverished repertory and declining standards, ballet at the Opéra, to quote a well-worn phrase, ‘tomba en décadence’. Critics at the turn of the century bemoaned its indecipherability, the result not only of dancers’ technical emphasis but of over-complicated plots and obscure gestural vocabularies. In a review of the Opéra’s 1907 creation Le Lac des aulnes, critic Pierre Lalo criticized the ballet scenario:

Ne pourrait-on imaginer des actions plus élémentaires, et mieux faites pour la pantomime, dont la signification se laisserait apercevoir plus aisément? . . . Le nombre des ballets intelligibles est excessivement petit.3

(Could we not imagine simpler action, better suited to pantomime, the meaning of which could be more easily perceived? . . . The number of intelligible ballets is extremely small.)

Reviewing the ballet for Le Monde musical, editor André Mangeot described a similar ‘incompréhensibilité’:

Cet argument est tellement clair et si bien rédigé que trois lectures consécutives ne nous permettent pas d’en découvrir le sens.4

(This scenario is so clear and well formed that three consecutive readings were not enough to make sense of it.)

Mangeot also made the point about technique becoming an end in itself – an end, even, to the eminence of ballet as art. His musings over the definition of dance are worth quoting at length:

La danse est-elle, comme l’ont toujours voulu les artistes, LA BEAUTÉ DANS LE GESTE, ou bien, comme les professionnels de la danse et la grande masse du public se le figurent, L’AGILITÉ DANS LE MOUVEMENT?

Si la première définition est exacte, il est malheureusement vrai que les exercices de chorégraphie auxquels nous assistons à l’Opéra ne sont pas de la danse. Si, au contraire, nous acceptons la seconde définition, l’Opéra est la grande école de Terpsichore, car jamais mollets féminins ne connurent dextérité pareille à celle du corps de ballet de notre Académie nationale de musique et de danse.

Est-il besoin de dire que, sous cette dernière forme, la danse cesse d’être un art? C’est un exercice adroit, aux multiples contorsions, qui demande infiniment de travail, car il exige des membres inférieurs des mouvements et des positions antinaturels, et l’on sait quelle peine il faut prendre pour violer la nature. Ces déformations engendrent inévitablement de la laideur, car la première condition de la beauté humaine est d’être conforme à la nature.5

(Is dance, as artists have always wished it, BEAUTY EMBODIED IN GESTURE, or, as dance professionals and the great majority of the public imagine, PHYSICAL AGILITY?

If the first definition is correct, it is a sad fact that the choreographic exercises we witness at the Opéra are not dance. If, on the contrary, we take the second definition, the Opéra is the grand school of Terpsichore, because female calves have never been as dexterous as those of the corps de ballet of our national academy of music and dance.

Is it necessary to say that, under this second definition, dance relinquishes its status as art? It is a skilful exercise, with multiple contortions that demand much practice, because of limbs that are not used to certain unnatural movements and positions, and because we know how much effort is needed to battle against nature. These deformations inevitably lead to ugliness, because the primary condition of human beauty is to conform to nature.)

Non-natural, non-dance, non-art: these harsh words from Mangeot underline the perceived sterility and irrelevance of ballet at the Opéra. More than this, the words contrast vividly with those bandied about two years later in reviews of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. The two companies, it seems, were polar opposites: one, a trite and tired residue of nineteenth-century ballet convention; the other, a fresh and frenetic band of exotic dancing ‘Others’. As is well known, French critics luxuriated in the Russian troupe’s perceived exoticism – at once ‘subtil’ and ‘grisant’ (‘intoxicating’), ‘sauvage’ and ‘barbare’ – as well as in the new brand of choreographic spectacle the Russians had to offer. But the Opéra and its ballets were not forgotten. A good deal of the journalistic ink expended on the Russian troupe was devoted to the instruction it could offer the national ballet. The Russians were ‘les professeurs slaves’, the French their ‘bons élèves’: ‘l’enseignement des Ballets Russes’ was a favourite journalistic topic.6

The press leaned first and foremost on decor, lamenting the Opéra’s taste for realism and visual excess, whilst promoting the Russians’ simpler and more suggestive style. According to the well-known critic and man-of-letters Camille Mauclair:

Le point le plus frappant de notre conception, c’est le désir obstiné de la vraisemblance immédiate et du réalisme de détail: réalisme élégant, certes, admettant le caprice ornemental et la changeante féerie des éclairages, mais réalisme tout de même et quand même . . . Le décor russe est compris au pur et simple point de vue de la peinture décorative dans sa mission essentielle: la suggestion émotive par le langage de la couleur, par le contraste chromatique . . . Tout consiste dans la richesse et la hardiesse de la tonalité. L’accessoire est réduit au strict nécessaire. Le dessin des silhouettes est complètement exempt du souci des détails.7

(The most striking aspect of our conception is the obstinate desire for an immediate true-to-life-ness and for realism in all its detail: an elegant realism, to be sure, allowing for ornamental fancies and changing enchantments of lighting, but realism all the same and even so . . . The essential aim of Russian decor follows the pure and simple point of view of decorative painting: emotive suggestion through the language of colour [and] chromatic contrast . . . Everything consists of rich, bold tones. Props are restricted to what is necessary. Outlines are sketched without any concern for details.)

Also observing these differences between French and Russian decorative tendencies was Jean-Louis Vaudoyer. In a lengthy review for La Revue de Paris, Vaudoyer described the effect of decor on the spectator:

Les décors russes sont synthétiques, et, refusant de distraire l’œil par mille petits détails ‘finis’ avec soin, ils se contentent, par des alliances de deux ou trois couleurs . . . de faire éprouver une impression très forte, et celle-ci permet au spectateur d’achever par l’imagination tout ce que des omissions aussi adroites laissent facilement deviner. Les décorateurs français, d’une habileté trop consciencieuse, font s’écrier au spectateur: ‘Comme c’est cela!’ Les Russes sont plus ambitieux et parviennent à nous faire dire: ‘Nos rêves sont vaincus.’ Onques avant eux le mensonge ne nous avait à ce point satisfaits et dupés.8

(Russian decor is synthetic, and, refusing to distract the eye with a thousand small, carefully ‘finished’ details, is happy, by the juxtaposition of two or three colours . . . to create a very strong impression, and this lets the spectator’s imagination fill in those skilful omissions. French stage designers, too conscientious in their talent, make the spectator exclaim: ‘That is how it is!’ The Russians are more ambitious and succeed in making us say: ‘Our dreams are defeated.’ Never before them had illusion so contented and deceived us.)

According to this formulation, the Russians’ economical use of stage props, along with their preference for vivid juxtapositions of colour, helped to offer spectators an imaginative licence, a free rein to conjure the stage world and indulge in personal fantasy. Audiences were thus assigned an active role; they were participants in the stage spectacle, necessary to its dramatic effect.9

Yet ‘un cours de décoration’ was not all the Russians had to offer. French critics also pointed to Russian choreography: not as something wholly original, but rather as an offshoot of the French ‘classical’ tradition exported to Russia in the late eighteenth century by a series of European (and, for the most part, French) choreographers.10 The irony of this was not lost on the French. Critics found it absurd that, whilst their own choreographic practice had become stilted and stale, that of the Russians – really, of the continuing French tradition – was uniquely expressive and dramatic. Diaghilev’s principals, in particular, were widely regarded as symbolically animate: Nijinsky was lauded not only for his virtuosic agility and weightlessness, but for the metaphysical condition he was thought to embody. In the words of Charles Méryel:

Nijinsky semble, comme on l’a dit, se dérober aux lois de la pesanteur . . . Nijinsky extériorise un élan intérieur . . . La plupart jouent ou dansent avec leurs corps: Nijinsky danse aussi avec son âme.11

(Nijinsky, as we said of him, seems immune to the laws of gravity . . . Nijinsky expresses an inner impulse . . . Most play or dance with their bodies: Nijinsky dances also with his soul.)

Quite the opposite, the dancers of the Opéra – even the highly regarded Carlotta Zambelli – were rarely anything more than ‘ravissante’ or ‘gracieuse’.12 They were defined in general by the dexterity of their limbs, not by any inner significance or expressive intent.13

That French critics saw room for improvement at the Opéra is clear. André-E. Marty, writing in Comœdia illustré, summed up:

Que les Français, à l’exemple des Russes, secouent un peu cette torpeur où ils menacent de s’alanguir, qu’ils perdent le goût fade pour le joli, qu’ils prennent le parti de subordonner le décor à l’action . . . qu’ils reviennent à leurs anciennes traditions en formant d’admirables danseurs; ils n’en perdront certes pas pour cela les admirables qualités classiques de goût et de mesure qui font leur gloire. Ils ne cesseront pas d’être eux-mêmes, mais le seront d’une façon plus large et plus vivante.14

(Let’s hope that the French, following the example of the Russians, escape a little from this torpor in which they threaten to languish, that they lose the insipid taste for prettiness, that they resolve to subordinate decor to action . . . that they return to their old traditions by training admirable dancers. They will certainly not lose the admirable classical qualities of taste and moderation that characterize their glory. They will not stop being themselves, but rather be themselves to the full, and in a more animated manner.)

But what of Marty’s prophecy? The question of the Russians’ influence on the Opéra is complex and multi-layered. There was no full-scale capitulation to Russian practice – no overhaul of the national ballet, no franco-Cléopâtre or Schéhérazade. The latter, in fact, was an idea that Ivan Clustine, ballet-master from 1911 to 1914, found preposterous. Writing in the popular music journal Musica, Christmas 1912, Clustine declared:

Quant à préconiser une influence des ballets russes sur les ballets d’opéra, ce serait folie. Ces deux formes d’art, dont la genèse s’oppose entièrement, n’offrent aucun point commun dans la réalisation. Styliser Coppélia avec des costumes rutilants et au moyen de décors aux tonalités multiples produirait une impression cocasse. Il n’est pire sottise que de changer le cadre où évolue une œuvre. Que l’on essaie de jouer Schéhérazade en ne se conformant pas aux principes qui animent la réalisation de ce ballet, et l’on rompra toute unité d’art.15

(To recommend that the Ballets Russes influence the ballets of the Opéra would be madness. These two forms of art, the geneses of which are entirely opposed, have not one point in common concerning their method of production. To stylize Coppélia with gleaming costumes and multi-tonal decor would be laughable. There is nothing more foolish than to change the context in which an oeuvre develops. Performing Schéhérazade without conforming to the ballet’s vital principles would destroy its artistic unity.)

Nonetheless, and despite Clustine’s protestations, several features of the Opéra’s post-1909 ballets, along with its institutional conventions and balletic policy, appeared to betray a Russian influence. The appointment of Clustine is a case in point. A Russian émigré previously engaged in Monte Carlo (and, before that, at the Bolshoi in Moscow), Clustine arrived in Paris to a flurry of press commentary on his nationality and choreographic agenda. His hiring was thought a direct attempt by the Opéra to imitate the Russian company; even he thought as much, maintaining, not without despondency, that inspiration too often came from the north:

Des gens bien informés – il en est toujours qui prétendent recéler la pensée des autres – affirmèrent que j’allais briser l’actuelle statue d’Euterpe. Une révolution éclatera! . . . Une révolution! méthode que l’on applique souvent au pays des tsars.16

(The well-informed – there are always some who claim to harbour the thoughts of others – claimed that I was going to crush the current statue of Euterpe. A revolution will break out! . . . A revolution! A method that people often apply in the country of the tsars.)

Clustine, although acknowledging his nationality with pride, harboured none of the revolutionary intentions that some thought an inevitable consequence of being Russian. He wanted, he argued, merely to rectify certain details: to promote the male danseur over the danseuse travestie (the female dancer dressed as a male and taking a male part); and to encourage the wearing of tutus only when dramatically appropriate.17 Nonetheless, these details, like Clustine’s appointment, were also thought imitative – further examples of the Opéra taking the lead from the Russian troupe. The Russians were known for abolishing conventional balletic hierarchy, foregrounding the danseur (and thus toppling the danseuse étoile from her pedestal) and doing away with cross-dressing. Their costume designs were equally notorious and often replaced the tutu with more dramatically suitable dress, including free-flowing tunics, harem pants and decorative body stockings.

As for the French ballets themselves, that seven works were produced in such close succession – La Fête chez Thérèse (1910), España (1911), La Roussalka (1911), Les Bacchantes (1912), Suite de danses (1913), Philotis (1914) and Hansli le bossu (1914) – was itself remarkable: not since the mid-nineteenth century had anything similar been accomplished. What is more, and according to Guest and Vaillat, several of the ballets invite comparison with Russian productions, particularly in terms of choreography and drama. Describing the inevitability of any Russian influence on the Opéra, Guest proposes a specific gestural equivalence between Les Bacchantes, from Greek mythology, and the Ballets Russes’ L’Après-midi d’un faune: a similarity of poses in profile, seemingly inspired by bas-reliefs.18 He goes on to describe a second correspondence, evoking the Opéra’s appropriation of Russian neo-Romanticism: Suite de danses, he writes, is a ‘replica’ of the Ballets Russes’ Les Sylphides, first performed four years earlier (itself an adaptation of the Maryinsky’s Chopiniana of 1907).19 Both works evoke ballet’s former Romanticism by means of tulle skirts, pointe slippers and a general etherealness; both are set in a moonlit park and to the music of Chopin; and both consist of a series of individual pieces strung together on a plot that is negligible in Suite and non-existent in Les Sylphides. Besides this neo-Romantic influence, there was an obvious infiltration of exotic subjects into the Opéra’s output. Vaillat, though less concerned than Guest with the business of Russian teaching, implies as much, enquiring after the thematic contingency of España, with its titular exoticism, and of La Roussalka, which leans heavily on Slavic legend.20

But there is a gap in both Vaillat’s and Guest’s accounts. Neither historian notes any correspondence – gestural, dramatic or otherwise – between the Russian repertory and La Fête chez Thérèse: indeed, Vaillat’s history locates Thérèse (1910) before the arrival of the Russian company in 1909. The sense of both accounts is that Thérèse was historically and temporally adrift, incongruous within a local balletic context and immune from contemporary influence. The bare bones of reception appear to support this, for whilst Thérèse received its premiere in 1910, archival sources suggest that plans for the production date back to 1907.

These circumstances – and the cohering idea of the ballet’s incongruity – serve as the launch-pad for this chapter, which will explore the hows and whys of Thérèse’s very nature, comparing and contrasting the ballet with other contemporary works. Needless to say, this kind of study involves some sleight-of-hand. Choreographed by ‘Mlle Stichel’ (real name, Louise Manzini), based on a libretto by Catulle Mendès and with music by Reynaldo Hahn, Thérèse suffers from a lack of reliable documentation, particularly on its gestural aspect. There is no surviving choreographic record or stage manual, and reviews offer vague and atmospheric descriptions of the production rather than any detailed gestural analysis. The commentary offered here thus focuses less on choreography than on other balletic parameters, those traceable through the surviving sources: Mendès’s libretto, the original publication of which has survived, and Hahn’s score – the annotated orchestral performing score (signed by the composer) and the piano reduction housed in the Bibliothèque-musée de l’Opéra. Together, libretto and score suggest scenario, setting, character and structure, not to mention the role of music as a storytelling agent. They also offer clues, if only partial ones, to dance style and placement, suggesting how dance might be associated with plot, character and scene.

Pursuing these clues is central to my project – a close reading of Thérèse, its visuals, narrative, structure and music. I also hope to suggest something of the ballet’s broader cultural resonance, inviting a review of the taxonomies by which histories of the contemporary dance scene are usually plotted and a reassessment of the dominant historiographical strategy itself.

Backward glances: scene and narrative

The stage was festooned with long dresses. Some were elaborate, bell-shaped creations, worn by characters with fancy coiffures and fans; others were made from muslin or gingham, accessorized with pinafores and bonnets; still more were in the making, half-stitched cuttings of satin, silk, gauze and tarlatan lying on a table, pored over by eager assemblers.

This was the setting of Thérèse, Act One: a fashion designer’s studio, with seamstresses attending to their clients’ demands, offering garments for try-on sessions and rhapsodizing on the tried-on. The dresses of course are a clue to the studio scene. The animate ones, filled with performing bodies, help differentiate between character and class, customer and employee; the inanimate suggest industry or work, as well as the article of trade. But both types, animate and inanimate, betray something beyond a local dramatic scene; for these were not dresses of a style or taste to suit 1910s Paris. Instead, they were vestiges from a bygone age, material residue of a former fashion that, along with other scenic elements, signalled a time other than the present day. In the words of critic F. Mobisson:

La mise en scène de La Fête chez Thérèse [est] un véritable enchantement . . . Le décor, le mobilier, les accessoires, les costumes, d’une rigoureuse exactitude, sont une reconstitution fort plaisante du style Louis-Philippe.21

(The mise en scène of La Fête chez Thérèse [is] truly enchanting . . . The decor, the furniture, the accessories, the costumes, rigorously exact, are a most pleasant reconstruction of the Louis-Philippe style.)

Louis-Philippe had reigned some seventy years earlier, in a period characterized by ostensible liberalism and reform, along with a marked historical consciousness: the king famously converted the château at Versailles into a museum dedicated ‘à toutes les gloires de la France’.22 Indeed, there is something of the museum about Thérèse’s Act One scene. Besides the quasi-authentic props (vases, dressing tables, curtains) and costumes, the stage was peppered with real-life remains. At Mendès’s request, portraits of some of the most famous French ladies of the day hung on the studio walls, reflected by mirrors and lit with a vibrant gold light. The writer Émile de Girardin, the duchesse d’Abrantès, the dancer Carlotta Grisi, the actresses Virginie Déjazet, Marie Dorval and ‘Rachel’ (Élisabeth Rachel Félix): these icons of the July Monarchy came to life in full material finery. They were all-consuming, inescapable; the studio was a sort of iridescent shrine.

So much was noted by the press. Journalistic nods to the scene – ‘exquis’, ‘charmant’, ‘ingénieux’ and, most important, ‘très français’ – were rife. Thérèse, on a visual surface at least, recalled French history, perhaps even in a manner similar to Louis-Philippe’s recycled chateau. Indeed, just as the ballet’s visuals appealed to a national heritage, its plot evoked a specifically balletic one.

Here is a short synopsis:

Seamstresses at work in Madame Palmyre’s studio are interrupted by their respective suitors. A scene of romancing ensues, but is cut short by the arrival of clients come to try on their outfits for Duchess Thérèse’s forthcoming ball. Their suitors disappear behind folding screens; the seamstresses welcome the customers, a party which includes dancers from the Opéra, as well as Duchess Thérèse herself. Suddenly, a folding screen falls to the ground: Théodore, a suitor in hiding, has accidentally knocked it over in an attempt to get a better view of Thérèse. Enraged that a man has witnessed her undress, Thérèse storms out of the studio, followed by an apologetic Palmyre. Théodore remains, enraptured by Thérèse, ignoring his once-beloved seamstress Mimi and her protestations of love. He kisses a glove left by the duchess as his jilted lover breaks down in tears.

Act Two stages the ‘fête’ of the ballet’s title: masked revellers entertain Thérèse and her guests with scenes of diegetic dancing, music and general buffoonery; Théodore, uninvited and disguised as a cavalier, pursues Thérèse. But Mimi has also sneaked in. Cornering Thérèse, she begs the duchess to relinquish her new suitor. Touched by the young girl’s sincerity, Thérèse dismisses Théodore, though not without blowing him a final kiss. Dejected, Théodore returns to his former lover, who waits with open arms. The revellers indulge in a final dance.

What is traditional about this? According to Opéra director André Messager, not a lot: ‘Ce qui nous séduisit, c’est que La Fête chez Thérèse est un ballet d’un genre tout nouveau à l’Opéra, c’est une chose intime, évoquant la vie et les costumes de 1840’ (What attracted us is that La Fête chez Thérèse represents a new type of ballet for the Opéra; it has something intimate about it, evoking the life and costumes of 1840).23 ‘Intimate’, certainly: Thérèse tells of a personal affair of the heart, a domestic intrigue set against a picturesque backdrop of (in Act One) an interior workplace and (in Act Two) a private party. But ‘a brand new genre’? Thérèse betrays little of the Russian-inspired exoticism or abstract poeticism that infiltrates contemporary works; and its local, anecdotal history seems out of place amongst the mythological settings and themes favoured by the Opéra. (Eight of the eleven ballets commissioned by the Opéra between 1900 and 1914 were based on legend.24) Yet the ballet was not wholly anomalous. The historical setting, historically authentic backdrop, opulent staging, elaborate plot, domestic intrigue and plot formulae (suspense, social contrast, cause-and-effect incidents): all these features invite comparison with the ballet-pantomime – the self-standing dramatic genre, combining dance and mime, that featured heavily at the Opéra during the July Monarchy, the period depicted in Thérèse.

Much is known of this double-barrelled species, thanks in large part to the work of Marian Smith.25 A few parallels with Thérèse are particularly worthy of note. Perhaps the most vivid concerns the centrality of a love story and certain amorous plot situations: a man’s love for and pursuit of a woman of higher social standing (in Thérèse, Théodore’s desire for the duchess); a love triangle or scene of romantic crisis at the end of the first act (Mimi’s desperation over her beloved’s newfound love interest); a woman’s attraction to a man, disguised, whose name and identity she does not know (Thérèse’s fondness for the masked Théodore).26 This last situation leads to an additional parallel, in that Thérèse also follows the standard ballet-pantomime in its staging of a masked ball. (The popularity of ball scenes in ballet-pantomimes of the July Monarchy is thought to result from their scenographic potential and narrative verisimilitude: the scenes provided a rationale for stage dancing and thus alleviated librettists’ concern for dramatic realism.27) There is also the matter of dramatic mood. The ballet-pantomime, Smith argues, was light-hearted and lightweight entertainment; ballet itself was considered inappropriate as a medium for conveying political and religious content, and more suited to romantic themes, happy endings and ‘soothing’, pastoral backdrops.28 Thérèse offers a similar ‘calm’: the ballet reconciles the on–off seamstress/suitor relationship amongst the celebratory festivities of a ball, denying any sombre connotations or sense of struggle.

What are we to make of these similarities? What do they reveal of Thérèse, its creative methods, motivations and general historical aura?29 My next section, on the ballet’s structure and stylistic shifts, will cast light on these questions with specific reference to Hahn’s score.

Backbone: the score

On a most basic level, a musical score can reveal a ballet’s structural divisions, its succession of ‘numbers’ or seamless, through-composed form. But a score can also indicate movement – by means not only of the mimetic and cartoon-like synchronization of contour, punctuation and rhythm (known as ‘mickey-mousing’), but of a more general coincidence of musical style and movement style. In Thérèse, two musical styles prevail: one is characterized by periodic phrasing, rhythmically distinct themes (often repeated, occasionally in different keys), solo obbligato textures, on-the-beat and metrically regular bass-lines, punctuated chordal endings or endings softer in dynamic and articulation, suggesting the winding-down of stage movement and the dispersal of dancing groups (see Example 2.130); the other is through-composed, changing continually in phrasing, metre, theme and key (see Example 2.2, of which more later). The former corresponds to scenes of dance – often set dances, extraneous to the plot and entitled ‘danse’ or some more precise descriptor (‘valse’, ‘menuet’). Here, metrical and phraseological stability tends to anchor dance movements to a codified aural pattern; easy-on-the-ear melodic material encourages a focus on the moving body. The latter style signifies scenes of mime: annotations include stage directions and, occasionally, words to be mimed by the dancers. This style follows the unfolding of drama on stage, as well as the shifting nuances of character and emotion.

Example 2.1 Hahn, La Fête chez Thérèse, Act One, scene 2, ‘La Contredanse des grisettes’.

Example 2.2 Hahn, La Fête chez Thérèse, Act One, scene 5, ‘Pantomime’.

An oscillation of these two styles in a ballet score of 1910 was not exceptional. Although the Ballets Russes, in their first season of 1909, had tended to dance to musique pure (music not written for dance), ballet at the Opéra was almost always accompanied by music of bipartite categorization: discrete and formulaic ‘numbers’ contrasted with passages of wandering affect. Yet what stands out in Thérèse is the concentration of each style – hence the concentration of dance and mime, even the concentration of ‘story’. In brief, of the Opéra’s ballets premiered between 1909 and 1914, Thérèse had the greatest proportion of through-composed music – that is, music to accompany mime. Just over half (52 per cent, by my reckoning) of Hahn’s score was devoted to music for miming, compared to roughly two-fifths of Lucien Lambert’s La Roussalka, one-fifth of Alfred Bruneau’s Les Bacchantes, and none of the orchestrated Chopin that accompanied Suite de danses.31 Moreover, in their own ways, La Roussalka, Les Bacchantes and Suite de danses all promoted dance: Suite de danses, as the title suggests, comprised a succession of dances with no intervening mime; La Roussalka featured characters, the Roussalki water spirits, whose supernatural movements resembled ‘classical’ gestures; and Les Bacchantes offered an act-length sequence of diegetic dances performed as part of Bacchus’s spiritual rite. This last ballet, in fact, appears less a mimed musical drama with dancing than a danced work with a modicum of miming. Of the twenty-one ‘numbers’, only four are labelled ‘pantomime’: ‘story’ is subordinated to the dancing spectacle, is almost entirely submerged.

One might wonder whether this narrative evanescence relates to changing dance practices elsewhere (the evolution of ‘modern’ dance, the famously non-narrative Les Sylphides) or to the now infamous literary conceptions of dance as a non-figurative ‘Idée’, an abstract sign without signified.32 But this would be to stray from the topic at hand. Thérèse, clearly, was devoted to storytelling: it offered roughly equal amounts of ‘ballet’ (set dance) and pantomime, thus devoting roughly equal time to virtuosic display and to action. Yet if this structural composition marked a point of departure from contemporary practice, it harked back to the 1840s genre introduced earlier. Thérèse, it appears, is a literal ballet-pantomime, a formal equivalent of the genre typified by its titular split of dance and mime.33

Back-chat: music and drama

Another angle from which to consider Thérèse’s score and its historical significance involves the coincidence of music and dramatic expression. Exploring the role of ballet music, needless to say, is a complicated business. There is little context for discussion, little archival material and little sense of how music closely allied with dance might sound, might mean. Nonetheless, the inevitable complications may be less severe with Thérèse: even as the ballet escapes gestural reconstruction, its scenes of pantomime, complete with stage directions and dialogue to be mimed, hint at the relation between music and the drama unfolding on stage.

One such scene has been mentioned already: the episode from the end of Act One in which Théodore, mesmerized by the sight of the duchess in déshabillé, snubs Mimi and her amorous declarations (Example 2.2). In this episode, two distinct musical figurations are obvious, at least in the opening thirty-seven bars. The first comprises off-beat semiquavers in duple time, oscillating thirds (at the start of each entry) and simple, top-heavy textures. The second, in a slower tempo and compound time, is textually thicker and more lyrical, and consists mainly of conjunct (and often chromatic) melodic motion. These two styles alternate throughout the scene: moreover, they do so in line with text and character. According to annotations in the score, the frenzied semiquavers mark an exclamation, question or action by Mimi; the more expressive music accompanies Théodore.

There is, then, a clear sense of musical dialogue, of characters linked to musical styles – styles that are themselves dramatically suggestive. Mimi’s off-beat snatches depict not only the agitation of her outbursts, but the aural impression of outbursting: the on-the-beat rests break the musical flow, creating short bursts of instrumental flurry; the undulating contours, widening intervals and occasional syncopation approach the inflections of speech, giving the music a ‘talking’ quality. (In Mimi’s first entry, the number of musical snatches equals the number of phrase she is to ‘speak’/mime: ‘verbal’/gestural and musical phrases line up.) As for Théodore, whilst his music lacks that ventriloquistic tendency (he is largely silent, after all), it helps communicate his mood. Not only is the soupy lyricism appropriate to his wistful, dream-like state, but it tends towards the two identifying themes of Thérèse, the subject of his reveries. The first of these themes – which both recur throughout the ballet – appears in bar 12 in an inner voice: this is a lilting melody, rising in contour and seemingly heading towards A major, until its interruption five bars later by an implied diminished seventh (on D♯) over a bass E. This last chord, which seems to highlight Mimi’s disturbance of Théodore’s reverie, is left unresolved as the tonality shifts to C♯ minor for Mimi’s next ‘speech’. The second identifying theme, beginning in bar 22, is an upper-voice modified-triplet figure, the final chord of which (a dominant ninth on A♭) also fails to resolve: Mimi’s fast notes recur (for the third time) in the next bar, again wrenching the tonality towards an unrelated minor key.

Théodore’s music thus conjures not only his dramatic mood, but the focus of his thoughts; Mimi’s music reflects her disposition as well as her mode of address. This loading of the score with narrative content – with metaphorical and real-time ‘voices’, aural reminiscences of character and other pictographic traces – continues throughout the scene: Mimi’s gesture to Thérèse’s portrait in an attempt to convince Théodore of the duchess’s noble status is accompanied by one of Thérèse’s identifying themes in a heavily articulated, chordal and fanfare-like guise (bar 46); Mimi’s collapse, following her pursuit of a departing Théodore, is synchronized to a low timpani roll breaking out of a rising chromatic line over four octaves higher (bar 74); and Mimi’s solitary crying at the end of the scene is attended by a sparse orchestral texture and a staccato melody played pianissimo by solo oboe and piano (bar 78). This last moment was singled out as one of the ballet’s highlights by critic Édouard Risler:

La scène – une page de poète – où Mimi . . . ‘pleure doucement’. Je ne connais guère d’impression plus triste que ces quelques notes . . . auxquelles se mêle, comme une orgue de Barbarie lointaine, le son grêle du piano.34

(The scene – a poet’s page – in which Mimi . . . ‘cries softly’. I hardly know of a sadder impression than these few notes . . . blending with the shrill sound of the piano, like a distant barrel organ.)

Risler’s words are worth noting; clearly, the critic was impressed by the music’s seeming poeticism, its ability to bring silent, moving images to life. He noted as much earlier in his review:

Le meilleur livret ne vit que par la musique qui l’anime, et celle de Reynaldo Hahn l’anime d’une vie qui lui assure une perpétuelle jeunesse . . . chaque page contenait une idée.35

(The best libretto lives only by means of the music that animates it, and that of Reynaldo Hahn animates with a life that assures the libretto a perpetual youth . . . each page contains an idea.)

Others spoke similarly of the music’s dramatic resonance. Robert de Montesquiou went so far as to describe the score as an active force, coaxing the characters into movement:

D’un bout à l’autre de ces deux actes, elle [la musique] a fait tourbillonner, avec une inlassable vélocité et un charme non moindre, des modistes, des duchesses, des gigolos en complets de casimir, des Gilles aux taffetas luisants.36

(From start to finish, the music, with relentless speed and no less charm, makes milliners, duchesses, gigolos in cashmere suits and Gilles in gleaming taffeta all swirl round.)

André Rigaud summed up:

Elle [la musique] est si étroitement liée à la poësie du sujet qu’elle est le sujet lui-même, l’esprit, la grâce, le charme . . . C’est à elle qu’on doit de voir tout ce qui est peint sur la toile et aussi tout ce qui n’y est pas.37

(The music is so closely linked to the poetry of the subject that it is the subject itself, spirit, grace, charm . . . It is through the music that we see all that is painted on the scenic canvas and also all that is not there.)

These comments endorse the impression of carefully wrought musical-dramatic effects; but they also strike a peculiar note. In the context of early twentieth-century ballet criticism, commendations of music’s dramatic effectiveness were scarce. For the most part, reviewers described French ballet music in unexceptional terms, often lamenting a perceived superficiality or surface gloss. According to Pierre Lalo, for example, Henri Maréchal’s score for Le Lac des aulnes followed the action precisely, but without energy, vivacity or life:

Est-elle [la musique] mauvaise? Non point. Est-elle bonne? Non plus. Elle est correcte, elle est consciencieuse, elle est sage, elle est modérée. Elle s’efforce honnêtement de suivre l’action, d’en exprimer avec exactitude les péripéties. Elle est d’un musicien qui connaît son métier . . . et tout cela serait parfait, si seulement cette musique était en vie. Le malheur, c’est qu’elle ne vit point du tout.38

(Is it [the music] bad? No. Is it good? No. It is proper, conscientious, restrained and moderate. It endeavours to follow the action closely, to express its events exactly. It is by a musician who knows his trade . . . and all that would be perfect, if only this music was alive. The misfortune is that the music is not at all alive.)

Five years later, critic Julien Torchet invoked a similar mediocrity in Alfred Bruneau’s score for Les Bacchantes, noting that the music would add nothing to Bruneau’s reputation.39 Another critic even suggested a reason for Bruneau’s troubles:

Il existe entre la Musique et la Danse, ou plutôt entre les Compositeurs et les Danseurs, un malentendu, que le ballet des Bacchantes ne parviendra pas encore à dissiper. Ce malentendu provient de ce que, à l’Opéra plus encore que sur d’autres scènes, la Danse ignore la Musique et la Musique ignore la Danse.40

(There exists between Music and Dance, or rather between Composers and Dancers, a misunderstanding that the ballet of Bacchantes will not yet succeed in clearing up. This misunderstanding is a result of the fact that, at the Opéra more than at other theatres, Dance ignores Music and Music ignores Dance.)

Here, of course, we are some distance from the lauded pictoriality of Thérèse. Shared amongst the above quotations is a sense of ballet music’s arbitrariness, a sense that runs contrary to earlier comments about Thérèse’s musical poetry and animation. The ballet’s incongruity in a contemporary context comes to the fore once again, inviting us to compare Hahn’s score with a couple of others.

Comparing scores

Let us begin with Maréchal’s Le Lac des aulnes and a scene, chosen almost at random, in which a magician’s daughter, Lulla, attempts to introduce her father to a sprite, Elfen, visible only to Lulla herself (see Examples 2.3a and 2.3b). A first point to note is the repetition of mime music at separate dramatic moments. Consider, for example, the G major motif of the ‘Largo assai’ (Example 2.3a, bar 2), used to accompany Lulla’s examination of Elfen. This motif recurs (albeit altered melodically) a few moments later (bar 8) when, following her father’s disavowal of the sprite’s existence, Lulla begins to play with Elfen; it is heard again, doubled at the octave, in the ‘Largo maestoso’ (Example 2.3b, bar 1). Such a musical recurrence may seem of only minor importance, perhaps reflecting an imperative of musical economy rather than any musical-dramatic coherence. Nonetheless, it may also alert us to a potential non-pictoriality about the music (what does it mean that the same motif accompanies actions of bodily inspection, play and dance?), and, more important, to a kinship between music for mime and music for dance. This is a second point to note: that mime music tends to borrow from dance, and vice versa. The motif of the ‘Largo assai’ is exemplary. Even on its first ‘mimetic’ appearance, this music has something dance-like about it, owing to those undulating flourishes, a general melodic expressivity and, not least, a lilting, waltz-like feel. (The  time signature, taken slowly, is likely to suggest a triple metre.) When the motif recurs at the ‘Largo maestoso’ it is granted full-scale waltz treatment: the entire mimed passage of the ‘Largo assai’ is arranged as a set dance, ‘ironed’ into a regular, periodic structure, complete with fanfare-like accompaniment.

time signature, taken slowly, is likely to suggest a triple metre.) When the motif recurs at the ‘Largo maestoso’ it is granted full-scale waltz treatment: the entire mimed passage of the ‘Largo assai’ is arranged as a set dance, ‘ironed’ into a regular, periodic structure, complete with fanfare-like accompaniment.

Example 2.3a Maréchal, Le Lac des aulnes, Act One, ‘Largo assai’.

Example 2.3b Maréchal, Le Lac des aulnes, Act One, ‘Largo maestoso’.

This blurring of styles may be significant: because there are plenty of occasions in the ballet when a similar motivic continuity is apparent (or else occasions when mime music approaches dance, if not becoming the subject of a danced scene itself); and because this blurring contrasts acutely with the musical specificity of Thérèse. An initial comparison of Maréchal’s and Hahn’s scores suggests a marked disparity of dramatic effect. Whilst Hahn’s music tends to be shaped by the immediate needs of text and action, belonging firmly in the diegesis, Maréchal’s participates less directly in the diegetic goings-on (here I disagree with Lalo, quoted earlier). The latter remains less a raconteur than a scenic cloth suggestive more of a general style than a specific substance – a cloth stitched from idiomatic snippets, gesturing to a mode of performance.

As for Les Bacchantes, what of its supposed ‘misunderstanding’ between ‘Dance’ and ‘Music’? Turning to the first ‘Pantomime’ scene of only thirteen bars, one finds a consistency of metre, a thick, chordal texture, regular harmonic progressions, question-and-answer phrases and a rounded form, with introductory staccato octaves and concluding sustained chords (Example 2.4). These features may well be dramatically suggestive: the chorale-like texture may evoke the ballet’s religious overtones, whilst the très lent tempo, the plodding rhythms and heavy, semiquaver articulation may conjure Bacchus’s nobility of character. But more intimate, moment-by-moment effects are absent. There is no ‘speech’ music (à la Mimi in Thérèse) and no local musical-dramatic synchronicity; ‘voice’ and ‘words’ are submerged. Indeed, this idea finds literal realization in a handful of passages from the ballet in which characters sing. Whilst one might expect these sung sections to help advance the action, to state plainly the words to be mimed, they tend to do the opposite. Singing occurs not in scenes of pantomime, but scenes of dance; vocal lines offer personal reflections on the stage goings-on rather than narrative exposition. Moreover, in the final sung passage (the penultimate number of the ballet), the singing voice is used purely for its sonic effect. There are no words at all, but merely the tuned murmurings of characters.

Example 2.4 Bruneau, Les Bacchantes, Act One, ‘Pantomime’.

This ‘neutralization’ of musical narrative could certainly generate further discussion – of the neutralization of narrative itself (mentioned earlier) and the development of more subtle means of musical characterization. For the present, though, it will be sufficient to register the contrast – between, on the one hand, Les Bacchantes and Le Lac des aulnes and, on the other, Thérèse. The last offers a musical-dramatic intimacy, a planned and patterned synchronization, that suggests little in the way of similarity with the other ballets of the period. Yet, and perhaps unsurprisingly, this synchronization may be reminiscent of an older balletic tradition: Thérèse draws from the same stock of musical-dramatic crutches as the 1840s ballet-pantomime.41 As Smith describes in her study of the genre, composers went to great lengths to tell a story, to provide a literal and transparent musical text made up not only of identifying themes and familiar signifiers for mood, feeling and geographic location, but of specifically balletic devices, notably the instrumental recitative.42 This device, designed to imitate the speech rhythms and contours of words to be mimed (written in libretti), features prominently in Thérèse. Mimi’s music, for example, constructs a straightforward signifying system that parallels verbal language: the music appears to ‘talk’, to ‘envoice’ the silent dancing character.

A second musical device favoured by ballet-pantomime composers was also employed by Hahn: his score is notable for its borrowings, especially from music with familiar connotative value – music thus able to directly facilitate spectators’ understanding of the plot.43 One of these borrowings may be of particular dramatic significance. Prior to the dress consultations of Act One, the seamstresses spot a familiar face amongst the clientèle; it is Carlotta Grisi, beloved étoile of the Opéra. Gathering around the ballerina, the seamstresses request a private performance. Grisi acquiesces, performing the waltz from Giselle to original music by Adolphe Adam. The seamstresses burst into applause.

From an interpretive standpoint, this scene offers a crowning stroke. Thérèse not only participates in an act of borrowing typical of the ballet-pantomime; it borrows from one of the most illustrious ballet-pantomimes of all. In other words, and to pull together the several strands of these pages, Thérèse thematizes the genre – literally, in its quotation of Giselle – whilst simultaneously offering a structural, narrative and musical restoration. What is more, following the seamstresses’ applause, Grisi teaches the Giselle waltz to Mimi, and the seamstress goes on to repeat the dance in full. This repetition not only highlights the historical signifier; the dramatized didacticism extends off stage and towards the spectators in the theatre. The audience also receives instruction in the ways of the waltz, reminded once again of Grisi, of Giselle and of those illustrious days of ballet at the Opéra.

It is but a small step from here to a ‘cultural-political’ reading of the ballet, one that speculates about motivation, agenda and reception. Thérèse’s references to the ballet-pantomime may be configured as tactics of edification, designed to moralize on a national balletic history; the ballet itself may be an exercise in self-promotion, a product of an Opéra seeking roots in its past, historicizing its own history as a means of self-glorification. Indeed, in its references to the 1840s, Thérèse evoked an era when ballet – its technique, terminology, aesthetics, practitioners and products – was explicitly French. The ballet-pantomime, as noted earlier, was an exemplary French species, created and developed by French practitioners; although it gained acceptance on many European stages (in Milan, Stuttgart and Vienna), its home was the Paris Opéra.

Of course, this ‘cultural-political’ argument might be made firmer and more compelling by recourse to the historical context of early twentieth-century ballet – to the ‘décadence’ at the Opéra, not to mention the success of the Ballets Russes. One might ponder the fact that, just as the Russians captivated Paris with their exotic dancing and decor, the national company withdrew into the traditions that enfolded it. The historical coincidence of Thérèse and the Russian seasons, then, may encourage us to think again about old oppositions: oppositions between companies and the men at their helm, but also between creative aesthetics, dramatic models and musical styles.

There is an additional opposition to consider, one that may signal the complexity of visual and musical signifiers, as well as the possibility of historical cross-currents. To explain, I shall turn to another of Hahn’s musical borrowings.

Back to reality? A counter-narrative

After her turn as Giselle, and her warm reception by Palmyre’s workers, Carlotta Grisi singles out the prettiest: ‘Toi, qui es-tu, petite? Tu es la plus jolie!’ The seamstress (played by Carlotta Zambelli) replies with the following mimed ‘speech’:

The words are not those of Palmyre’s apprentice; the accompanying music is not that of Hahn. Quoted here is a well-known poem by Alfred de Musset, to music by Frédéric Bérat – a poem that confirms the identity of the seamstress as the blonde-haired grisette of 1840s Parisian subculture, a certain Mademoiselle Pinson (see Example 2.5).44 What is offered here, then, and on a most basic level of character, is another reference to the period of Thérèse’s assumed heritage, a reference ‘realized’ through one of its most iconic characters: the Mimi of Musset, of Henri Murger, Puccini and Leoncavallo.45

Example 2.5 Hahn, La Fête chez Thérèse, Act One, scene 3, ‘La Chanson de Mimi Pinson’.

Yet Mendès’s grisette shares few characteristics with her historical ancestors: with Musset’s thoughtful, insouciant heroine; with Murger’s pert, wilful coquette (and Leoncavallo’s similarly drawn gold-digging flirt); and with Puccini’s fragile muse.46 The Mimi of Thérèse – incidentally, the real protagonist of the ballet – is a different creation: confident and self-assured, she demonstrates a mature initiative, winning back her lover through practical pleas and, unusually, surviving the ordeal. One might even describe her narrative portrayal as forgiving. Not only does Mimi forgive her lover’s wandering affections, but we, the audience, tend to forgive her more irksome characteristics: her spectacular balletic prowess (she learns the Giselle waltz in record time, trumping Grisi’s version with her own, six times the length); the aggressive, if sincere, language of her plea to Thérèse (‘Oh! Don’t love him! Tell him not to love you! Give him back to me!’); and her nagging interrogation of Théodore at the end of Act One.

Mendès may have modelled this balletic Mimi, if not on the character’s historical ancestors, then on her seamstress sisters of 1910: the ‘Mimi Pinsons’ of Gustave Charpentier’s Parisian night school, the Conservatoire Populaire de Mimi Pinson, founded by the composer in 1902. These namesakes – young, underprivileged working women (mainly shop-girls and seamstresses) – were offered classes by Charpentier and his cadre of distinguished colleagues in piano, popular song, dance, pantomime, declamation and, interestingly, fencing. By January 1910, roughly five hundred ‘Mimi Pinsons’ attended the school on the Élysée des Beaux-Arts, performing in public concerts at the Tuileries, the Place des Vosges and the Place de la Nation, and even attending national events (such as the unveiling in the Paris suburb of Suresnes of Émile Derré’s bust of Zola). The students became symbols of social advancement and equality; Charpentier’s school, to quote scholar Mary Ellen Poole, represented ‘the last gasp of Fourierist “art for the masses” as a didactic, morally uplifting, and pleasure-giving force’.47

Mimi, too, may represent an ideal of social parity – an upward mobility that resonates with Charpentier’s institution. In a manner not dissimilar from that of the composer’s best students, Mimi triumphs over her domestic and social circumstances. More specifically, she triumphs over Thérèse: as one critic noted of the ballet, ‘C’est le triomphe de la grisette sur la grande dame.’48 (Incidentally, this triumph owes to a musical coercion: Mimi’s identifying theme, granted an extra-diegetic quality, is literally ‘heard’ by Théodore and Thérèse during their passion, prompting the duchess, out of sympathy, to return Théodore to the seamstress.) Thérèse herself loses her lover, her clothes and even her dignity. Humiliated over Théodore’s presence during her undressing in Act One, scene 3, she continues to dance in only a petticoat. Critic Robert de Montesquiou was appalled: characters of noble rank rarely danced on stage (owing to librettists’ concerns for verisimilitude), let alone in their underwear.49

As well as this broadly socialist resonance, the character of Mimi may also evoke contemporary politics of gender and identity. On this subject, Hahn’s score is once again evocative, in terms of both the amount of material allotted to Mimi and this music’s linguistic authority. The mime scene between Mimi and Théodore examined earlier will help illustrate (Example 2.2). Clearly, there is a marked disparity between the quantity of music assigned to each character (Mimi receives roughly twice as many bars as Théodore) – a disparity that might simply reflect Théodore’s dreamy, faraway state and Mimi’s desperate resolve. But Mimi’s music is by far the more idiomatic, as well as the more rhetorically persuasive. She has a distinct and distinctly recognizable identifying theme (the Bérat melody), as well as characteristic semiquaver ‘chatter’ – ‘chatter’ that, often beginning with a tonal wrench (suggesting the relentlessness of her discourse), overwhelms Théodore’s mimetic attempts. Théodore’s music, on the other hand, is hazy and vacuous. Here and earlier in the ballet, he is granted no identifying theme and tends instead merely to borrow music from one of his women. He seems disinclined to articulate himself clearly or individually, to enter into dialogue or to address the audience in monologues; he seems disinclined to ‘talk’ at all.

So much is evident – and the ensuing gender implications equally so: Mimi represents feminine authority, assertiveness, even aggression; Théodore embodies masculine submissiveness and docility. These gendered representations, which inverted the essential divisions of bourgeois life, are characteristic not only of the ballet in question, but of the early 1900s, a period that witnessed the rise of feminism and feminist periodicals, easier access for women to higher education and professional careers, a declining birth-rate and new divorce laws.50 This general historical condition shored up the image of the femme nouvelle (the bourgeois ‘she-man’), a woman newly visible and equal to men (in social and professional station, as well as physical presence), independent and educated, and keen to campaign for her rights. One example of such a woman may be Mlle Stichel, the Opéra’s ballet-master and the choreographer of Thérèse. Previously engaged at the Châtelet, Paris, and the Théâtre de Monte-Carlo, Stichel was one of few women to occupy the much-vaunted position.51 She was also one of few to contest her authorial rights, taking legal action against the Opéra in a bid for an equal share (with librettist and composer) of Thérèse’s royalties and authorship. The bid, pleaded in front of the Tribunal Civil de la Seine on 9 February 1911, was successful, Stichel claiming victory for choreographers – and for women – nationwide.52

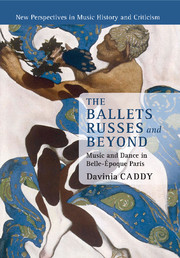

A second example may be Mimi herself. The character – her actions, her fate and not least her music – may be representative, a theatrical incarnation of the social and gendered ideals of bourgeois life. Even her costume is suggestive. To rewind to the dresses with which the ballet began: all the dresses on display had long skirts, the length being historically authentic in suggesting 1840s fashion (see Figure 2.1). That Mimi’s skirt was long, though, was something of an irregularity. As Zambelli described in an interview with Le Miroir:

Ce fut une belle affaire. Les chroniqueurs d’alors s’en emparèrent. Les vieux abonnés étaient stupéfaits et déconcertés. Une robe longue à la place du tutu! . . . Une danseuse dont on ne voyait pas les jambes! . . . C’était la révolution!53

(It was a fine business. The columnists of the time seized hold of it. The old subscribers were stupefied and disconcerted. A long dress instead of a tutu! . . . A dancer whose legs one could not see! . . . It was a revolution!)

Zambelli went on to describe how one male spectator failed to recognize her backstage following the premiere and made the mistake of asking her name.

Je gardai mon sérieux et lui répondis:

– Zambelli.

Le vieil abonné eut un sursaut de surprise. Il s’excusa, un peu confus . . . Il ne m’avait pas reconnue . . . Il ne pouvait pas me reconnaître: la robe longue, songez, monsieur, la robe longue!54

(I kept a straight face and replied:

– Zambelli.

The old subscriber gave a start with surprise. He excused himself, a little confused . . . He had not recognized me . . . He could not recognize me: the long dress, think, Monsieur, the long dress!)

Figure 2.1 Zambelli as Mimi Pinson, La Fête chez Thérèse (1910).

Functioning as a protective shield, the skirt was not only exceptional on a balletic body more accustomed to knee-length (and above) gauze; it screened the body itself, concealing Zambelli’s identity – especially her sexual identity as an object of the male gaze. Yet the skirt also lent the dancer, and the character she played, some of the physical modesty and sobriety associated with the image of the femme nouvelle, an image that overturned the traditional type of decorative, eroticized femininity. This new, desexualized image even struck a chord with the dancer’s offstage social status and reputation. As Zambelli made plain in an article for the journal Je sais tout, the Opéra’s étoiles of the early twentieth century were far from the sexual trophies of the mid-nineteenth; they were rarely offered the lavish gifts, salaries and attention received by their historical counterparts. Instead, the Opéra’s brightest stars thought of themselves as mere civil servants, self-made working girls working hard to make a living. Like Mimi herself.55

Backing up (conclusion)

Considered together, these ideas project a striking image of Thérèse and its resonance with contemporary culture – with the French feminist movement, with social reform and even with the practical matter of dancers’ social status. The ‘contemporary’ should be underlined, for all this discourse on ‘real life’ c.1910 leads us far from the original historical signifier – the French ballet-pantomime of the 1840s. A new line of argument emerges, one that may well be of signal importance to our understanding of the institutional project of the Opéra. Talk of didacticism, for example, might refocus on social instruction, on the amelioration of the female working class; previous notions of nationalism and nostalgia might cede to contemporary ideals of womanhood and the equality of classes and sexes.

Yet these two historical signifiers – the one retrospective, the other specific to the belle époque – can in fact coalesce: in other words, the contemporaneous currency of the ballet can endorse its generic heritage. As Marian Smith explains, the ballet-pantomime was prone to a mirroring of social relations, particularly gendered ones. Plots tended to uphold notions of masculine power and feminine submissiveness, to teach object lessons in social and sexual relations.56 Thérèse, then, fits the bill. Like the ballet-pantomime of the 1840s, the ballet leans heavily on contemporary gender ideology. Only now, of course, this ideology has been inverted, the image of the decorative and eroticized ballerina replaced by that of the long-skirted Mimi, merely one of a crowd.

This argument – almost too convenient – should not make for a miserable conclusion. The position of Thérèse within an institutional and historical context throws up an important question about the relationship discussed at the start of this chapter – between the Paris Opéra and the Ballets Russes. Both companies were active in a period of intense debate about ballet, tradition and influence, a period that saw ballet-makers strive for self-preservation, self-aggrandizement and the wholesale capitalization on what was then a new and prominent public and critical interest. The Ballets Russes are often considered in this context. Historians have long described – and celebrated – the troupe’s innovative aesthetic, its relation to tradition and its ‘uncanny’ awareness of contemporary trends and tastes. But what would it mean to discern these same characteristics in the French ballet, the official and supposedly ‘conservative’ company? What if Thérèse was as self-conscious and strategic as the Russian offerings? The broadness of the ballet’s frame of reference, the number of onstage/offstage analogies, the multiply-allusive and iconic characterization, the composite score: these features may be contingent not only on a pre-established generic mould, but on a contemporary artistic climate in which ballet, for the first time in a good few decades, was actively seeking to make itself relevant, to communicate with a newfound audience.

These ideas run deep into the complexities of the historical scene, as well as the historiographical assumptions of ‘innovation’ and ‘Otherness’ that saturate the scholarly literature. In airing the ideas here, I hope simply to encourage a more wide-angled view of early twentieth-century ballet. For if the usual story of the period glorifies (foreign) individuals and initiatives, then revisionism might value continuities and cohabitation, might consider the French and the Russians (the self and the ‘Other’) in the same frame.

An early version of this chapter appeared in the Journal of the Royal Musical Association, 133/3 (November 2008), pp. 220–69; see www.informaworld.com. I am grateful to the journal’s anonymous reviewers for their careful and considered comments.

1 Lynn Garafola, Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes (1989; repr. New York: Da Capo, Reference Garafola1998); Léandre Vaillat, Ballets de l’Opéra de Paris (Paris: Compagnie Française des Arts Graphiques, Reference Vaillat1943); Olivier Merlin, L’Opéra de Paris (Fribourg: Hatier, Reference Merlin1975); and Ivor Guest, Le Ballet de l’Opéra de Paris: trois siècles d’histoire et de tradition (1976; repr. Paris: Flammarion, Reference Guest2001). Guest offers a particularly comprehensive survey of the productions and goings-on at the Opéra, as well as a catalogue of its balletic repertory, principal dancers and ballet-masters.

2 For recent revisionist accounts of ballet Romanticism, see Lynn Garafola (ed.), Rethinking the Sylph: New Perspectives on the Romantic Ballet (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, Reference Garafola1997).

3 Pierre Lalo, ‘La Musique’, Le Temps, 3 December 1907; clipping, F-Po, Dossier d’œuvre, Le Lac des aulnes.

4 André Mangeot, ‘La Danse à l’Opéra et le ballet “Le Lac des aulnes”’, Le Monde musical, 30 November 1907, pp. 331–2 at p. 331.

5 Ibid., p. 331.

6 For these terms, see , ‘Les Ballets Russes’, Musica-Noël (1912), pp. 255–7.

7 Camille Mauclair, ‘L’Enseignement de la saison russe’, La Revue, 1 August 1910, pp. 350–60 at pp. 350–1.

8 Jean-Louis Vaudoyer, ‘Variations sur les Ballets Russes’, La Revue de Paris, 15 July 1910, pp. 333–52 at pp. 349–50.

9 This idea of active spectatorship meshes neatly with a comment from Lucien Alphonse-Daudet. Writing in Comœdia illustré, the critic described the intimate relationship between audience and art kindled during Ballets-Russes performances: ‘Nous ne sommes pas seulement spectateurs de ces danses, nous y jouons un rôle et c’est pourquoi elles nous bouleversent.’ See his article ‘6e Saison des Ballets Russes au Châtelet’, Comœdia illustré, 15 June 1911, pp. 575–8 at pp. 575–6.

10 Mauclair, for example, writes: ‘Nous avons été étonnés de reconnaître, dans la chorégraphie russe, les principe[s] de l’ancienne chorégraphie française, absolument oubliés aujourd’hui, importés en Russie à la fin du XVIIIe siècle et au début du XIXe, par nos maîtres de ballet.’ See his ‘L’Enseignement de la saison russe’, p. 355. More recently, Richard Shead has offered an account of the heritage of the Russian ballet in his Ballets Russes (London: The Apple Press, Reference Shead1989), pp. 10–13. Shead notes the line of Frenchmen – from Jean-Baptiste Landé, through Charles-Louis Didelot, to (most famously) Marius Petipa – who helped introduce European ‘classical’ dance to Russia.

11 Charles Méryel, ‘L’Adieu aux Ballets Russes’, Comœdia illustré, 15 June 1912, pp. 749–55 at p. 750.

12 Two press reports that describe Zambelli in such terms are Adolphe Jullien, ‘Revue musicale’, Journal des débats, 1 December 1907, and Henry Gauthier-Villars, L’Écho de Paris, 27 November 1902. (Gauthier-Villars is better known as Willy, the first husband of the novelist Colette.)

13 On this point, the words of Mangeot are once again evocative. In his review article of Le Lac des aulnes, quoted earlier, Mangeot singles out Zambelli as the personification of the sterile, stilted and specifically French style of dancing he so deplored. More than this, he issued Zambelli with an invitation to submit her dancing to the science of ‘la cinématographie’ – a series of successive photographs that could capture the individual gestural components of her movements and thus endorse (or not) their essential ‘beauté’. Zambelli’s initial response was to send Mangeot her calling card (‘Carlotta Zambelli, Mille remerciements’); according to Mangeot, this was tantamount to admitting defeat – admitting that her dancing could not withhold serious gestural analysis or the attention of the qualified artists (painters and sculptors) he planned to engage. Zambelli replied again, granting Mangeot a half-hour conversation in which she explained how the fluidity of her dancing denied the sort of ‘décomposition’ that Mangeot had in mind (‘lorsqu’on veut l’arrêter sur une pose, ce n’est plus ça’). But Mangeot remained unconvinced: his conversation with Zambelli was pleasant enough (as was the dancer herself), but she could not really answer his questions about ‘les lamentables traditions dont elle est la plus haute incarnation’. The dialogue between Mangeot and Zambelli can be found in the pages of Le Monde musical, 30 November, 15 December and 30 December 1907.

14 André-E. Marty, ‘Encore les Ballets Russes’, Comœdia illustré, 15 August 1909, pp. 459–60 at p. 460. Vaudoyer closes his 1910 piece with something similar, expressing a hope that French choreography and stage design might follow the Russians’ lead; see his ‘Variations sur les Ballets Russes’, p. 352.

15 See , ‘Ballets Russes et Ballets d’Opéra’, Musica-noël (1912), p. 245.

16 Ibid.

17 As it happens, the fate of the tutu provoked something of an uproar in the popular press, several critics bewailing the garment’s seeming demise. In response to an article entitled ‘Est-ce la fin du tutu?’, Clustine wrote specifically of his intentions, claiming that, whilst the tutu might be appropriate for a supernatural character, it was unbefitting of peasants and religious folk; see Louis Delluc, ‘À propos du “tutu”’, Comœdia illustré (n.d.); clipping, F-Po, Dossier d’auteur, Ivan Clustine.

18 See Guest, Le Ballet de l’Opéra de Paris, p. 149. It seems likely that the gestural language of Les Bacchantes was also influenced by the bas-relief postures of Cléopâtre and Narcisse, as well as Faune.

19 Ibid.

20 Vaillat, Ballets de l’Opéra de Paris, pp. 47–56.

21 F. Mobisson, Le Journal (n.d.); clipping, F-Po, B 717 (a collection of press cuttings about Thérèse, mostly dating from the weeks surrounding the ballet’s premiere).

22 The seminal account of Louis-Philippe’s conversion of the chateau from royal residence to ‘musée national d’histoire’ is Pierre Francastel, La Création du musée historique de Versailles et la transformation du palais, 1832–1848 (Paris: Les Presses Modernes, Reference Francastel1930). For more on the king’s preferred, some would say politicized, version of the past, see Michael Marrinan, Painting Politics for Louis-Philippe: Art and Ideology in Orleanist France (New Haven, CT, and London: Yale University Press, Reference Marrinan1988), and Petra ten-Doesschate Chu and Gabriel P. Weisberg (eds.), The Popularization of Images: Visual Culture under the July Monarchy (Princeton University Press, Reference Chu and Weisberg1994).

23 Clipping from L’Écho de Paris (n.d.); F-Po, B 717.

24 Bacchus, premiered on 26 November 1902, was about the god of wine and his romance with an Indian princess betrothed to the king; La Ronde des saisons, 25 December 1905, was based on a Gascon legend in which Oriel, a sprite, beguiled the young Tancrède; Le Lac des aulnes, 25 November 1907, was inspired by Goethe’s ‘Erlkönig’; España, 3 May 1911, was an exotic fable about Spanish dancers; La Roussalka, 8 December 1911, was based on a Russian myth (and a poem by Pushkin) in which a woman, having drowned herself when separated from her lover, returns as a water spirit to claim him; Les Bacchantes, 30 October 1912, was loosely inspired by The Bacchae of Euripides and told of conflict between Bacchus and the Theban king; Philotis, 18 February 1914, was about a wealthy, love-struck dancer from Corinth battling against the will of Apollo; and Hansli le bossu, 22 June 1914, followed an Alsatian folk tale about a hunchback. The three non-mythological commissions were Danses de jadis et de naguère (Dances of old and of late), Thérèse and Suite de danses. The ballets Javotte and Namouna were also staged at the Opéra during this period, but were recreations.

25 Marian Smith, Ballet and Opera in the Age of ‘Giselle’ (Princeton University Press, Reference Smith2000).

26 Details of the July Monarchy ballet-pantomimes that foreground such romantic themes can be found in Smith’s exhaustive table of ‘plot situations’ characteristic of the genre; ibid., pp. 26–7.

27 Smith discusses the issue of verisimilitude, noting librettists’ ‘acute sense of what was proper and improper subject-matter for the ballet-pantomime’; ibid., p. 66.

28 Ibid., pp. 71–2. To account for this lighter tone, Smith points to the public’s perceived connection between ballet, the body and sex. According to Smith, the overt objectification and sexualization of the danseuse, both on stage and off, steered ballet towards amorous themes, private realms and seductive impulses.

29 It is important to note a potential red herring: that Thérèse was in fact labelled ‘ballet-pantomime en deux actes’. Whilst this generic designation seems to confirm the above-mentioned parallels, in fact it lays a false trail. Several ballets of the period were labelled ‘ballet-pantomime’ (including Le Lac des aulnes, La Roussalka and Les Bacchantes), though most lacked any of the dramatic characteristics of the 1840s genre. From period press reports on ballet and its definition, one may discern that the label as used in the early twentieth century referred not to any appropriative or retrospective impulse, but rather to a ballet’s narrative bent: ‘pantomime’ merely signified the presence of action over ‘pure danse’.

30 The contredanse, indicated in Example 2.1, developed from the English country dance introduced at the French court in the 1680s; including circle, square and long-ways formations, it became popular in urban society throughout the eighteenth century and into the nineteenth, until ousted from the floor by the quadrilles and round dances of the waltz and polka.

31 I arrived at these fractions with reference to the published piano reductions of each ballet (in the absence of annotated autograph scores, répétiteurs and recordings): I simply added the number of bars of set dance in each score, and, assuming the remainder (with the exception of the scene-setting passages at the beginning of each act) to be action music, calculated the proportions accordingly. My calculations are admittedly approximate.

32 The writings of Stéphane Mallarmé are especially well known; see his ‘Ballets’ (1886), Crayonné au théâtre; repr. in Œuvres complètes, ed. G. Jean-Aubry and Henri Mondor (Paris: Gallimard, Reference Mallarmé, Jean-Aubry and Mondor1945), pp. 303–7.

33 Smith notes the proportions of Giselle, perhaps the most famous ballet-pantomime of the 1840s: fifty-four minutes of mime to sixty minutes of dance; see her Ballet and Opera in the Age of ‘Giselle’, p. 175.

34 Édouard Risler, review of Thérèse, untitled (n.d.); clipping, F-Po, B 717.

35 Ibid.

36 Robert de Montesquiou, ‘Une collaboration entre Devéria et Lancret à propos de La Fête chez Thérèse’ (n.d.); clipping, F-Po, B 717.

37 André Rigaud, ‘La Fête chez Thérèse à l’Opéra’ (n.d.); clipping, F-Po, B 717.

38 Pierre Lalo, Le Temps, 3 December 1907; clipping, F-Po, Dossier d’œuvre, Le Lac des aulnes. Curiously, the sort of musical superficiality criticized by Lalo had previously been considered necessary to a successful ballet score. An article in Le Voltaire (8 March 1882) maintained that ballet composers should think only on the most superficial of musical levels. (Even more curious, this comment was made in response to a score for the ballet Namouna composed by Pierre Lalo’s father Édouard. The music of the more senior Lalo was considered ‘neuve’, ‘originale’ and ‘personnelle’ – and thus far from the requisite ‘superficielle’.)

39 Julien Torchet, Hommes du jour, November 1912; clipping, F-Po, Dossier d’œuvre, Les Bacchantes.

40 André Mangeot, Le Monde musical, 30 October 1912; clipping, F-Po, Dossier d’œuvre, Les Bacchantes.

41 This idea has an interesting footnote. Of the three scores for Thérèse housed in the Bibliothèque-musée de l’Opéra, two reveal a number of cuts that, to judge from handwritten scrawls and adhesive tape, were made after the ballet’s premiere (and presumably realized on the ballet’s recreation at the Opéra in 1921). A couple of the cuts are from scene-setting music: the opening of Act Two, as the curtain goes up on Thérèse’s garden; and the end of Act Two, scene 2, an atmospheric passage entitled ‘Clair de lune’. A couple more are of passages from set dances, including sixteen bars from the Act Two ‘Menuet’. But most of the cuts are from action scenes. One is particularly conspicuous: a passage from Act Two, scene 3, in which Mimi’s identifying theme (the piano melody heard to accompany her tears at the end of Act One) signals, according to Mendès’s directions, the character’s dramatic presence on stage. It is of course tempting to wonder whether these cuts reflect a larger objective, perhaps a culling of musical mimeticism in line with 1920s trends.

42 Smith, Ballet and Opera in the Age of ‘Giselle’, pp. 97–123.

43 See ibid., pp. 101–10. Smith includes a detailed list of the borrowed extracts in ballet-pantomime scores from 1777 to 1845 (pp. 104–7).

44 De Musset’s poem, first published in 1845, is included in his anthology Poésies nouvelles (1851; repr. Paris: Gilbert, Reference Musset1962), pp. 161–2.

45 I should note a further, equally glaring backward glance to the mid-nineteenth century: the ballet’s title draws on a poem by Victor Hugo (included in Les Contemplations, published in 1856) as the pictorial basis for Act Two.

46 An insightful account of Mimi Pinson’s literary and stage characteristics can be found in Allan W. Atlas, ‘Mimi’s Death: Mourning in Puccini and Leoncavallo’, Journal of Musicology, 14/1 (Reference Atlas1996), pp. 52–79. Other studies that explore Mimi and her Bohemian heritage include Jerrold Seigel, Bohemian Paris: Culture, Politics, and the Boundaries of Bourgeois Life, 1830–1930 (New York: Viking, Reference Seigel1986); Arthur Groos and Roger Parker (eds.), Giacomo Puccini, ‘La bohème’ (Cambridge University Press, Reference Groos and Parker1986); and Jürgen Maehder, ‘Paris-Bilder: Zur Transformation von Henry Murgers Roman in den Bohème-Opern Puccinis und Leoncavallos’, Jahrbuch für Opernforschung, 2 (Reference Maehder1986), pp. 109–76.

47 Mary Ellen Poole, ‘Gustave Charpentier and the Conservatoire Populaire de Mimi Pinson’, 19th-Century Music, 20/3 (Reference Poole1997), pp. 231–52 at p. 231.

48 Journal des débats, 20 February 1910; clipping, F-Po, B 717.