Berlin’s grand hoteliers of 1932 had not created the business model they were using. They inherited it, the culmination of more than a century of experience in Europe and the United States. There, the world’s first grand hotels emerged in the first half of the nineteenth century as part of the transportation revolution underway since the eighteenth century, when technological and infrastructural improvements increased travel and tourism in Europe. Hotels first emerged to answer the demand from a new traveling public for new standards. Largely middle class, this roving customer base insisted on greater privacy and cleanliness than older hostelries had provided. Hoteliers responded by modernizing and standardizing commercial hospitality across vast distances. Contributing to the ascendancy of the burgeoning middle classes, hotels as sites of bourgeois sociability and business became reflections of bourgeois values.Footnote 1

The extension of rail networks in the mid-nineteenth century concentrated this traffic in cities, especially those at the nexus of regional, national, and international lines, such as Berlin. There, as in London, Paris, and Vienna, grand hotels arose to accommodate the influx. The urban grand hotels of the later nineteenth century shared six features.Footnote 2 First, an urban grand hotel had to have rooms numbering in the hundreds so that an economy of scale could, at least theoretically, pay for public spaces on ground floors. Second, these varied, large, and sumptuous public spaces had to outshine competitor hotels and even the finest houses to the extent that locals and travelers would opt to meet there rather than in private spaces. Third, rates had to be higher than at most hostelries to ensure an elite clientele. Fourth, advanced technologies such as elevators, gas lighting, and radiator heating had to be available. Fifth, service must be thick on the ground so that elite guests missed none of the comforts of home. Sixth and finally, fine food, wine, spirits, and other beverages needed to be provided in-house to ensure self-sufficiency and to increase revenue. In short, the grand hotel had to be able to fulfill a guest’s every need and at a cost that still promised profits. That meant establishing economies of scale, putting a price on all services and products, and finding opportunities for vertical integration – for example, buying and running wine import and export businesses to control prices and capture extra profits.

Although the Prussian capital waited longer than Paris and London for such a hotel, the rapid industrialization and expansion of Berlin prepared the way for the sudden emergence of grand hotels after 1871. From the early nineteenth century, Berlin’s urban area reached farther and farther north, toward a new district of factories and workers’ housing, and west and southwest, toward inland port facilities and new rail depots. Amid the thoroughfares between the new infrastructure in the southwest and the old city center in the northeast, Berlin’s first grand hotel, the Kaiserhof, went up in 1875. Its home, the intermediate district of Friedrichstadt, now supplanted the old city as the center for commerce, entertainment, and administration, especially after the unification of Germany and the elevation of Berlin to the status of imperial capital in 1871.

An influx of indemnity payments from France after its defeat in the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71) and the liberalization of the laws of incorporation resulted in the foundation of thousands of limited liability joint-stock companies, including the Berlin Hotel Corporation (Berliner Hôtel-Gesellschaft). Its board, through the sale of shares, was able to raise enough capital to build the Kaiserhof. Still under construction, it became a model of modern hotel organization when Eduard Guyer, Europe’s foremost expert on commercial hospitality, included an exegesis on the blueprints in his 1874 Hotelwesen der Gegenwart (Hotel Industry of Today), an instant classic in business literature.Footnote 3

Guyer’s study of the building, especially its cellars, and his further prescriptions on staffing and management, indicates the Kaiserhof and other grand hotels’ status as liberal institutions par excellence. The Kaiserhof system – that is, the hotel’s infrastructure and technologies, its organizational hierarchies, and the established models of guest-staff relations – mirrored the liberal order of the day and reflected its central irony:Footnote 4 The free movement and association of the minority upstairs depended on the economic domination and political subjugation of the majority downstairs.

With the emergence of a dozen or so additional grand hotels in Berlin, a professionalized upper class of corporate officers and on-site supervisors dominated the field of hotel management. From on high, and with huge, poorly remunerated workforces in their thrall, these professional hoteliers still struggled to turn a profit. In turn, the hotels’ corporate boards of directors established a pattern of blaming the state and the workers for the shortfalls, rather than any inherent weaknesses in a business model that stipulated two or even three staff members per customer. The labor requirement hobbled grand hotels from the start and became their core weakness. Even a modest increase in wages would bring the enterprise to its knees. In all its fragility, the grand hotel as a liberal institution, much like the era’s liberal constitutions, disenfranchised the majority for the material benefit and prestige of the minority.

Early Grand Hotels

In the eighteenth century, hôtel meant an aristocratic residence within the walls of the city of Paris. Such a townhouse served as a nobleman and noblewoman’s home away from home, with room for guests and all the luxuries of a principal seat in the country.Footnote 5 Nineteenth-century usage of the word hôtel retained associations with elite, urban hospitality but added a commercial tinge and went beyond the French context. By the mid-nineteenth century, the word “hôtel,” retaining its circumflex accent even outside France into the twentieth century, meant a commercial establishment that rented individual guest rooms for a price and provided most of the services of a middling-to-elite household.Footnote 6 These modern hotels distinguished themselves from the inns and taverns (Gaststätten) of the eighteenth century by selling a higher standard of service and privacy.Footnote 7 Some of the earliest new hotels catered only to people of rank, as was the case in England, but an increasing number of establishments welcomed people regardless of status at birth.Footnote 8 The advent of a sizable bourgeoisie with money to spend, the overcoming of barriers to geographic mobility, and an increasing internationalization of commercial and social life contributed in the 1820s and 1830s to the formation of this new institution, the hotel, that could accommodate the new traveling public.Footnote 9

The first hotels to appear were at spas and in cities in the United States, Britain, France, Switzerland, the Low Countries, and German lands. Early examples included Nerot’s Hotel in London, Corre’s Hotel in New York City, the Royal Hotel in Plymouth, and the Hotel Badischer Hof (opened 1809) in Baden-Baden, where hospitality entrepreneurs had transformed a Capetian monastery into a resort complex of ballrooms, game rooms, dining rooms, baths, gardens, and galleries. More spa hotels cropped up in the ensuing decades in Baden-Baden, Wiesbaden, and other German and Swiss watering places. Meanwhile, in the cities, hoteliers began to build or adapt extant buildings into luxury hotels. By 1850, moneyed visitors to Geneva and Zurich could choose among several up-to-date hostelries behind imposing facades. Inside, they could expect public parlors, partitioned for quiet conversation, and private, well-appointed guest rooms on the upper floors.Footnote 10

An increasing number of Europe’s hotels catered to all functions of daily life. For a fee, a stranger could sleep, dine, socialize, entertain, and, if necessary, recover from an illness – all under one roof and as if at home. The hotels also became sites of class formation, the development of bourgeois-specific outlooks, attitudes, and behaviors – places where the bourgeoisie from all over Europe and the United States convened, conversed, and passed judgment.Footnote 11 Hotels even facilitated the accumulation of wealth and connections by offering spaces for free association at the intersection of multiple lines of communication, transportation, and capital. The economic-integrative function of early hotels was most pronounced in American cities. As early as the 1830s, for example, Barnum’s Hotel in Baltimore designated rooms for business meetings and commodities trading. Similar establishments in New York, Philadelphia, Boston, and New Orleans even contributed to the social, political, and economic integration of the republic, as A. K. Sandoval-Strausz has shown. Beyond these locations, hotels proliferated in port cities, on major north–south roads, and on east–west canals.Footnote 12

The first hotels depended on older modes of transportation, but as the newest conveyance, trains, extended across Europe and the United States in the mid-nineteenth century, hotel industries came to rely on the railroads for customers, supplies, and opportunities for growth. Railroads also shifted hotel development to those cities at the intersections of multiple lines. In some cases, new junctions created new towns, while in other cases the junctions concentrated streams of people and goods on established settlements. As travel times and expenses diminished, more people took to the rails. In expanding the market, the railroads also enabled the creation of ever larger hotels.Footnote 13 At mid-century, there were several such properties with rooms in excess of 100. The term “grand hotel” came into use specifically to distinguish the bigger hotels of the 1850s–70s from the smaller hotels of the 1800s–40s.Footnote 14 The first such urban grand hotels in Europe were the railroad hotels of Great Britain, where rail networks spread earliest and fastest.Footnote 15

Small and makeshift, the Prussian capital’s luxury hostelries still occupied structures first built for residential use, a distinct disadvantage: Quirky layouts meant that a single traveler might be asked to share a room with a total stranger even at some of the better establishments. Landing one’s own room did not necessarily guarantee privacy, either, because some rooms were accessible only by passing through another. Public space downstairs, however pretty, did not suffice, either. The best houses offered just two parlors – one for men and one for women – and a cramped ballroom or banquet hall. But even visitors willing to put up with all these deficiencies had trouble finding accommodation, since Berlin had too few hotels.Footnote 16

Berlin’s First Grand Hotel

In Berlin, grand hotels became possible only with the unification of Germany in 1871 and as a result of changes to the laws governing how corporations could form. These changes made it feasible to raise enormous amounts of capital for industrial and commercial enterprises while limiting the liability of shareholders – hence the contemporary name for the period 1871–73: Gründerzeit. “The era of founders” referred not to the founding of the empire as such but rather to the establishment of thousands of limited liability joint-stock corporations.Footnote 17 These formations enabled hoteliers to raise the fabulous sums necessary for their capital-intensive enterprises.

Meanwhile, the influx of people and goods to the city center fueled a speculative boom in the real estate market west of the old medieval core, in the city’s future hotel district. Friedrichstadt and Dorotheenstadt, long the preserve of Berlin’s titled and well-to-do, thus emerged in the later nineteenth century as an intensified zone of commercial activity and became the meeting grounds for Berliners of all districts. Workers, white-collar employees, shoppers, and tourists arrived at newly constructed intra- and interurban railroad stops, which connected to the streetcar lines already in use. The elevated Friedrichstraße station went up in 1878 at the northern frontier of Dorotheenstadt, along the River Spree, in view of Feuerland (Fire Land, the unofficial name of the city’s metalworking district) and the Mietskasernengürtel (Tenement Belt) to the north. In the west, Leipziger Platz pulled together myriad horse and then electric tram lines, which discharged passengers near Potsdamer Platz, one of the busiest squares in the empire, and the Potsdam and Anhalt rail stations. Farther southwest sat the enormous freight depot and one of the busiest ports of the Landwehr Canal. Most waterways, rails, and roads led to Friedrich- and Dorotheenstadt, which together formed the undisputed center of the new Berlin and the site of its first grand hotel.

Berlin’s first hotel corporation, the Berlin Hotel Corporation, was amalgamated in 1872 by its first chairman, the liberal wheeler-dealer Adelbert Delbrück. Through the 1860s, Delbrück had taken an active role in the German National Union (Deutscher Nationalverein), a liberal organization composed of the middle strata of German society – manufacturers, professionals, small business owners, and master artisans – which was committed to obtaining liberal reforms from above, by means of a unified Germany under Prussian leadership. The German Progressive Party (Deutsche Fortschrittspartei, DFP), the liberals’ umbrella party of the 1860s, also counted Delbrück as one of its leaders.Footnote 18 According to Friedrich Albert Lange, the philosopher and former DFP member, Delbrück and the other party bosses constituted “a small but influential Berlin clique,” liberal in outlook but “distinguished by a Junker-like” aloofness and arrogance.Footnote 19

Delbrück’s confidence derived from success. He was becoming a titan of finance and industry, especially after the liberalization of the laws governing the formation of corporations. He founded or helped found several conglomerates: the German Construction Corporation of Berlin (Deutsche Baugesellschaft zu Berlin), the Corporation for Construction Works in Berlin (Actien-Gesellschaft für Bau-Ausführungen in Berlin); the Berlin Construction Consortium (Berliner Bauverein); Hinsberg, Fischer & Co. Banking Consortium of Barmen (Barmer Bank-Verein Hinsberg, Fischer & Co.); Donnersmarck Iron Works (Donnersmarckhütte); the Upper Lusatian Railroad Corporation (Ober-Lausitzer Eisenbahngesellschaft); and, finally, Deutsche Bank. Delbrück was its first chairman.Footnote 20

Delbrück’s board members at the Berlin Hotel Corporation also came from Germany’s industrial and financial elite. Georg Siemens presided with Delbrück and others over Deutsche Bank. Siemens also had an interest in a financial services firm with another of the Berlin Hotel Corporation’s board members, Eduard von der Heydt. The son of former Prussian finance minister August von der Heydt, Eduard sat on several boards in addition to that of the Berlin Hotel Corporation, including a real estate and construction corporation and two insurance companies, one of them incorporated in the United States. His partner in the American venture, Gustav Kutter, resident of New York City, also sat on the board of the Berlin Hotel Corporation, as well as the boards of companies involved in coal mining, import-export services, and shipping by rail and steamship. The other board members of the Berlin Hotel Corporation held similar positions and assets. All liberals, most of these men played roles in the financial and economic reforms of 1848, the failed revolution that nonetheless had lasting, liberalizing effects on the Prussian and then German economy. Julius Kieschke, for example, had entered the civil service in 1848 and then the Prussian Ministry of Trade (Preußisches Handelsministerium) and the executive office of Königsberg. He was mayor of that city when he joined the first board of the Berlin Hotel Corporation.Footnote 21

The Berlin Hotel Corporation quickly raised the money for its debut venture, an establishment to rival the grand hotels recently opened in Vienna for the World’s Fair of 1873. By the end of that year, the corporation had purchased twelve lots on or adjacent to Berlin’s Ziethenplatz, a major crossroads in the government district.Footnote 22 The board persuaded the city to create a new street directly to the south to ensure that the new hotel would be the first in Berlin to occupy a freestanding structure.Footnote 23 They called the property Kaiserhof (Emperor’s Court), signaling the arrival of a hostelry in line with Berlin’s newly achieved status as an imperial capital.

For the first time, private citizens of the Prussian capital succeeded at changing the direction and style of development in the city center.Footnote 24 Corporate capitalism had allowed them to do it – to raise the funds, to acquire the land, to command the resources to lobby the government, which had stakes in the neighborhood. New government ministries, departments, and offices sprang up after unification, and many of them occupied buildings around the future Kaiserhof. The project would go on to supplant important buildings on Ziethenplatz, which had once housed the Prussian capital’s French and Italian embassies as well as several notable eighteenth- and nineteenth-century residences.Footnote 25

The transformation of Friedrichstraße, especially the intensification of activity there, was already underway before the foundation of the empire, but the pace of development increased in the 1870s. Berthold Kempinski opened his first restaurant on Friedrichstraße in 1872. His was among many large new establishments, including the Kaiser-Galerie shopping and amusement arcade (1873), the Admiral’s Palace baths (1874), and the Café Bauer (1878). Before these arrivals, owners of the city’s fine hotels had chosen sites away from commercial activity, typically farther north, on or near Unter den Linden, the representative boulevard connecting the royal palace to the Brandenburg Gate.Footnote 26 The Kaiserhof changed that pattern by opening in the center of a booming commercial district and thus acted not only as a hostelry but also as a place of respite for well-heeled Berliners, including bureaucrats and businessmen.

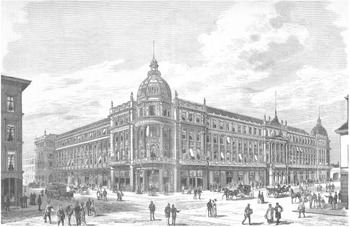

The Kaiserhof dominated the neighborhood, attesting to the financial power of Berlin’s new limited-liability corporations (Figure 1.1).Footnote 27 The rectangular facade had a perimeter of 310 meters and rose five floors above the pavement. A balustrade over the cornice lent additional height. A gigantic palazzo, the building featured a piano nobile over the mezzanine and an arched colonnade, in relief, of mock rusticated stone on the ground floor. The design also resembled Vienna’s colossal apartment houses of recent years, particularly the Ringstraße’s Heinrichshof.Footnote 28 A local referent was the German emperor’s palace, the Stadtschloss (City Palace), distinguished by its occupation of an entire city block.

Figure 1.1 The Hotel Kaiserhof, 1877

This first establishment of the Berlin Hotel Corporation was indeed a monumental intervention in the capital’s built environment, and critics took note. Before the hotel even opened, the Deutsche Bauzeitung disparaged the undertaking: “Obviously, the architecture … can never quite be interesting,” since it had to accede to the demands of the business model – in this case, the need to house “rooms of nearly the same size” in rows ad nauseum.Footnote 29 The critic’s misgivings reflected a more general response to the new large-scale commercial architecture. The utilitarian core of the Kaiserhof project was incompatible not just with precepts of beauty but also with any kind of architectural integrity. The facade in this case was an effort to mask what was un-beautiful – utilitarian – about the building’s interior, a result of the architects’ attention to function over form.Footnote 30 But when the hotel opened on October 1, 1875, the reviews turned laudatory. With Emperor Wilhelm I in attendance, the public had the chance to tour the sumptuous interiors. Ten days later, however, a fire broke out in the building, spread through the upper floors, and destroyed most of the guest rooms as well as the areas behind the front entrance (Figure 1.2).Footnote 31 No one was injured, and the blaze, in its way, generated spectacular publicity.

Figure 1.2 Contemporary illustration of the fire at the Kaiserhof on October 11, 1875

Socialists were quick to react. A contributor to the Neuer Social-Demokrat, a press organ of the Socialist Workers’ Party of Germany, announced the irony to readers: “Another creation of the Kaiserzeit, the splendid hotel on the Wilhelms- and Ziethenplatz, which carries the proud name ‘Kaiserhof,’ has suffered damage in the first days of its existence.”Footnote 32 The article identified the culprits as “bankers and large-scale industrialists,” as well as a few “princes” or nobles given to financial speculation. Creating enormous and mighty monuments to the German Empire and their own vanity, these men, according to the journalist, forgot to do their homework. They built bells too big to be rung (Cologne Cathedral) and towers too awkward to be admired (the Victory Column in Berlin, which people had taken to calling the “Victory Asparagus” instead); the latest was a hotel too big to safeguard from fire. Implied was the charge that these men’s obsession with gold, glitter, and grandeur had caused them to neglect the more mundane aspect of fire safety and thereby endanger the populace, putting money before people.Footnote 33 Correct or not about where to lay blame, the article’s author became the first of many to use a Berlin grand hotel as the setting for a drama about the hypocrisies of the powerful and propertied classes.

In the end, successful insurance claims and the emperor’s public support guaranteed reconstruction. The Kaiserhof reopened on the anniversary of its inauguration, on October 1, 1876. Baedeker described the property as “the largest and most elegant of Berlin’s hotels … comfortably outfitted in the style of the greatest Parisian and London hotels.”Footnote 34 Newspapers, too, emphasized the Kaiserhof’s many luxuries and its comparability to Viennese establishments.Footnote 35 The yearbook of the Berlin Association of Architects (Architekten-Verein zu Berlin) dwelled on the property’s opulence while quietly bemoaning the destruction of a few “residential buildings of value” – the embassies, especially.Footnote 36 But in 1878, the Kaiserhof proved itself even more useful to diplomats than the chanceries and palaces. That year the property served as the hotel of choice for statesmen who were in town to participate in the Congress of Berlin, which took place across an adjacent square.Footnote 37 With all its gas lamps aglow, the Kaiserhof amplified Bismarck’s message to the delegates about Germany’s place in the new world order. This palace hotel showcased imperial ambitions even as it reassured foreigners with offers of peace and civility. To keep that peace, managers, owners, and their architects had to keep the classes apart and unequal.

Grand hotel buildings employed an architecture of extreme inequality, affording space, privacy, and safety, according to station.Footnote 38 Meanwhile, a system of regulations controlled the dress and comportment of workers, as well as their interactions with the guests. This was a managerial vision of a hierarchy undergirded by architecture, elaborated by regulation, and relegated to the basement, hidden from view.Footnote 39

The Kaiserhof’s cellar became the standard for the cellars of other grand hotels in Berlin. It provided workspace for the hotel’s hundreds of workers who kept the hospitality machine running. In effect, they were confined to the lowest grade amid the heat, fumes, and din of service on an industrial scale. And yet, the cellar was not quite a factory. It lacked any expanse of shop floor. Instead, dozens and dozens of walls and doors separated workers from each other, from white-collar employees, from managers, and from the guests. Where workers did interact with guests – and only a minority did – workers’ uniforms and manners rendered them only marginally visible. They were supposed to be extensions of the system – unavailable personalities, of the hotel more than in it.

The cellar was the hotel’s principal site of production, the attic its tenement. In this way, the allocation of space mirrored that of bourgeois and aristocratic houses of the nineteenth century, but the Kaiserhof was of a different order.Footnote 40 Here lay servants’ quarters to sleep hundreds, kitchens to feed thousands, and laundries to boil bedlinens by the ton. At this scale, the work became more specialized, more monotonous, and more dangerous than in a manor house or urban palace. The pressures on workers were different, too, and perhaps greater. Hotel workers, unlike their domestic counterparts, were obliged not only to feed the elite but to do it at a profit.

The architects and owners of the Kaiserhof made the building plans, including cellar floor plans, available well before the opening of the hotel itself, using many of the projections as advertisements. More than architectural renderings, these floor plans and relief sketches were promises, visions, and prescriptions, as the hotel expert Eduard Guyer understood when he included them as exhibits in Das Hotelwesen der Gegenwart.Footnote 41 Guyer’s book quickly became the standard for how to build and operate a grand hotel.Footnote 42

With guest experience in mind, Guyer advised architects to design cellars that would trap as much noise and as many smells as possible.Footnote 43 Four decades later, in 1910, another expert, Paul Damm-Etienne, wrote more plainly. His principal concern was body odor. Sweating workers might produce a miasma that threatened to contaminate the food, he reasoned. The solution was not to install mechanical ventilation systems to cool the cellars. Instead, Damm-Etienne told hoteliers to provide more sinks and more soap.Footnote 44

Managers did in fact struggle to contain the smells and sounds of the cellars. The boilers, heaters, and pumps ran all day and night with only chimneys, transom windows, and air shafts for ventilation. What air was left to breathe contained coal dust, residue from the fuel that kept the machines running. This dust, along with soot, smoke, and water vapor, emanated from the cellar’s smoldering core, where men stoked furnaces and operated other heavy machinery and where steam, heat, dust, and fumes spewed from open fires and filterless grates. In the surrounding warrens, still more workers sorted, lifted, carried, and distributed goods and raw materials by hand or by cart. Around the periphery, in the kitchens, bakers finished bread and pastries in gigantic ovens. Dishwashers – people, not machines – pumped in scalding water so they could clean china by hand. From the laundries, wastewater flowed in torrents as women transferred bedsheets, towels, and table linens from cauldrons to mangles. The Kaiserhof’s cellar was a sweltering dungeon of the industrial age (Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3 The Kaiserhof cellar, 1877

The sharp delineation of space, as well as the order in which the architects, Hermann von der Hude and Julius Hennicke, arrayed rooms and facilities, showed an abundant concern for the productive division of labor and for the qualitative distinctions between guest and staff space – distinctions which reflected the architects’ and owners’ profit motive, as well as their view of class relations. Plans for the cellar would result in an environment that limited workers’ access to light, air, mobility, and privacy, the very privileges being sold to guests upstairs. This regime measured social class by the extent to which a subject could maintain health, freedom of movement, and privacy. In the service of productivity but also of the maintenance of class power, Hude and Hennicke’s cellar did nothing to spare workers a state of undignified living and unending toil.

Conditions aside, the building code made it impossible for hoteliers to house all of their workers in cellars. The attics, on the other hand, were suitable so long as their ceilings were high enough.Footnote 45 The Kaiserhof’s attic, like any other, would have been frigid in winter and sweltering by June. Technically on the sixth floor of the building, Kaiserhof workers’ sleeping quarters lay right under the eaves. (Small windows were hidden from view by a high balustrade over the cornice.) Large, sex-segregated rooms slept multiple people under low, raked ceilings. Staircases connected the attic to the guest floors directly so that workers could be roused and called to duty in the middle of the night. As in bourgeois and aristocratic households of the period, privacy and peace were luxuries only for the employers; servants had neither.Footnote 46

But attic sleepers might have had it better than their coworkers unlucky enough to have their beds in the cellar. Together with a workshop and chambers for the water and gas meters, basement bedrooms for hotel and kitchen workers spanned the building’s eastern side; these had smaller windows below street level. Away from the street lay rooms without windows or with only one window opening onto a lightless airshaft that had been given over to a steam pump. One such machine stood directly in front of the only window, wedged into a corner, of the men’s dining room, where hundreds would have taken meals in shifts, since it occupied less than thirty square meters. Across the hall and toward the center of the building was the women’s dining room, smaller than the men’s and windowless, surrounded by water heaters, air heaters, and food stores.Footnote 47 The swelter, noise, and crush were functions of the building’s design.

Among the loudest and hottest spaces were the kitchens, which sat underneath the guests’ dining room and covered more than 600 square meters (exclusive of storage, a prep kitchen, and kitchens for the café concession and staff meals). Some ninety people labored here elbow-to-elbow over open flames and scalding water. To the heat, noise, and danger of the kitchens, meanwhile, the front cellar provided a striking contrast. In an area larger than all the gastronomy spaces combined, thousands of bottles of wine rested under controlled and quiet conditions, with whites on the eastern, cooler, darker side and reds on the western, warmer, lighter side. The cellar manager and technician, who sat atop the cellar hierarchy, had their offices down here. The plans had spared these managers, and the wines, the full asperity of the rest of the cellar.

Directly upstairs, the Kaiserhof’s ground floor of public rooms for guests was something else (Figure 1.4). In its scale and layout, it resembled a department store, another site of conspicuous consumption in the metropolis.Footnote 48 Architects of department stores and grand hotels had envisioned the same optics, after all – upon entry, a guest’s gaze took in the glowing expanse. She might cast her eyes from one rich detail to another, one option for respite and pleasure to another, before settling on exactly what she wanted.Footnote 49 And from the outside, the main entrance of the Kaiserhof, like that of a department store, was easily recognizable, with the house’s name affixed over the arches of a generous portico. Coming through this entrance, guests would have witnessed what made the Kaiserhof a hotel on par with the best of larger, more established capitals: the hotel’s public interior.

Figure 1.4 Ground floor of the Kaiserhof, 1877

Never in Berlin had the public rooms of a hotel been granted so much space and expenditure. The allocation of areas for shops evoked the arcades of Parisian, Viennese, and London hotels, while the provision of smaller social rooms for intimate conversation owed much to the Swiss example and lent a domestic scale to these parts of the ground floor. Finally, through its organization around a central axis, the ground floor facilitated motion. The axis drew guests from the entry to the hotel’s grandest spaces, thereby making evident the ground floor’s spectacular dimensions. Then, having passed through the public, commercial spaces, guests were encouraged to move to the semi-private, domestic spaces nearby.Footnote 50

The least domestic feature of earlier grand hotels in Berlin and elsewhere, particularly the Kaiserhof, was the courtyard (Figure 1.5). The Kaiserhof’s building plans labeled the courtyard an anteroom (Vorsaal), emphasizing its function as the meeting place before passage to the adjoining dining room, breakfast room, or parlors. A glass roof shielded the 330 square meters below from rain and cold. Terraces on three sides provided access to the principal public rooms, making the court a pass-through, a way station, and public piazza in one, the social and spatial center of the Kaiserhof.Footnote 51 Its decor was nationalist, monarchist, and magnificent, appropriate to the room’s public function as a showcase for status and a space for public heterosociability.Footnote 52

Figure 1.5 The Kaiserhof courtyard, 1877

The architecture signaled this heterosocial functionality by supplying both masculine and feminine ornamentation. The Doric (severe, masculine) order balanced the Ionic (soft, feminine), while the seven full-length portraits of Emperor Wilhelm I, in various military uniforms, complemented some dozen female caryatids in soft, flowing drape.Footnote 53 These features framed interior windows that opened into public rooms on the ground floor and guest rooms above, so that the courtyard’s associations with masculinity and femininity were further complicated along the lines of public and private. Even the scale of the space was softened by its protectiveness. Gilt surfaces and underfloor heating likewise mitigated the outdoor aspect, an effect achieved by natural light and wrought-iron lampposts, and helped classify the court as an area of indoor-outdoor, public-private, masculine-feminine hybridity.

In general, however, male-female interactions were kept to a minimum in the Kaiserhof’s public rooms. Rules and design conventions placed the female patron somewhere between guest and worker in the hotel hierarchy, which dispensed space, luxury, and comforts according to class. A woman could enter the banquet hall, for example, only if in the company of a male chaperone. (This was also the case if she wanted to book a guest room.) Indeed, the hotel barred single women from most spaces, relegating them to a remote, rear-facing ladies’ parlor (Damensaal). The women’s lavatory (note: singular), tucked behind the ladies’ parlor on the ground floor, had one sink and one toilet. Conversely, the men enjoyed large lavatories (note: plural), each with space for several sinks and toilets. These inequalities reflected and reinforced the privileged status of certain guests over others – in this case, men over women.Footnote 54

What female guests lacked in access to amenities, space, and mobility, they made up for, somewhat, in their rights to make demands of staff, consume luxury goods and services, and sleep and dine as well as money could afford. This was hospitality at a price, after all, and the architects, Hude and Hennicke, designed the upper floors, with guest rooms, to reflect and reproduce divisions even among guests. First- and second-floor ceilings were the highest, and these levels contained the largest and most richly decorated guest rooms, as well as six parlors. Most of these parlors offered privileged views, either of Wilhelmplatz or Ziethenplatz, and could be connected to adjacent rooms via communicating doors, allowing the transformation of rows of guest rooms and parlors into apartments. This was ideal either for visiting families or long-term residents. Even if most of its guests were not traveling with children, the Kaiserhof earned the moniker “family hotel” (Familienhotel) through its provision of such suites on the lower floors.Footnote 55

A further innovation came with the rooms off corner parlors, the Kaiserhof’s finest bedrooms. A small private hall connected each chamber to the public corridor and adjacent parlor and thus acted as a sound and light lock, minimizing the disturbances associated with such a large hotel and ensuring privacy and peace. By contrast, the smaller, cheaper rooms in the rear of the first two floors had no such provisions for sound mitigation. Several opened onto narrow light wells with machinery at the bottom. The most modest of all these backrooms lay on the building’s third and fourth floors. Here, compact rooms best suited such single travelers as businessmen and couriers. Their rooms had lower ceilings and simpler furnishings and fittings than the rooms on lower levels.

Nonetheless, a few common factors united all four upper floors, with a total number of guest rooms at around 240, for as many as 400 people.Footnote 56 On each floor, dozens of rooms shared eight toilets and one bath, and no rooms were en suite, a luxury on offer nowhere in Berlin at the time. Most bathing could be accomplished with washstands in each of the rooms, and servants were always on hand to fetch hot water and remove wastewater. Chamber pots and workers to service them likewise made up for the paucity of water closets. These practices – the use of labor in lieu of plumbing – were common among the rich, who had yet to adopt the faucet and drain for the maintenance of their hygiene, even in Berlin’s newest apartment houses.

For the Kaiserhof, Hude and Hennicke had borrowed the European apartment house convention that placed the finest rooms on the second floor, the middling rooms above that, and workers’ and servants rooms higher still, with one added distinction: The Kaiserhof plan meant to segregate guests not only on the basis of class or income but also on the basis of gender, with the least dense areas reserved for women with their husbands and children and the most tightly packed for single male travelers. Although all guests could enjoy the amenities of the ground floor, the guestroom levels above incorporated material and architectural distinctions of income and social position and ensured that the lower guestroom floors would be populated more by married couples and families, the upper by single men.Footnote 57

As much as the grand hotel brought people together, its design kept them separated along lines of gender and class.Footnote 58 On the public, ground floor, female guests would find their movements prescribed by gendered conventions that required a chaperone in any of the spaces except the diminutive ladies’ parlor at the back corner of the building. Workers would labor under surveillance in dank, dangerous, dirty, toxic environments. The extent to which these visions of a segregated society became reality, after the fulfilment of Hude and Hennicke’s plans, is hard to measure, since worker testimony for the period before 1914 does not survive, nor does the architecture itself. Nevertheless, the plans and prescriptions afforded workers and women limited room for maneuver at the Kaiserhof.

Berlin’s Next Grand Hotels

The Kaiserhof was Berlin’s only grand hotel for just a few years. The city’s second such property, the Central-Hotel, opened in 1880 and integrated seamlessly into the capital’s intra- and interurban train lines.Footnote 59 Nine thousand square meters of land across from Friedrichstraße station had been acquired by its parent company, the Railroad Hotel Corporation (Eisenbahn-Hotel-Gesellschaft), which was itself owned by the Hotel Management Corporation, one of the principal hospitality companies in the city. The lots fronted Friedrichstraße, Berlin’s premier commercial thoroughfare and one of the longest streets in the city. It housed cafés, shops, arcades, hotels, theaters, and other amusements. The Central dominated this activity and fed it with customers, much as the Kaiserhof did several streets to the south. What made the Central different from the Kaiserhof was its position directly across the street from a station entrance. This unparalleled proximity to the railroad helped classify the Central as a “through-traveler’s hotel” (Passantenhotel). The target guest was someone in town for a short period to conduct business or rest for the night before connecting to other trains.Footnote 60 Capitalizing on the concentration of industry to the north and commerce and government to the south and southeast, the Central-Hotel was more American in style and function than the Kaiserhof, which was farther from the train stations.Footnote 61

Nevertheless, the Railroad Hotel Corporation had engaged the same architects, Hude and Hennicke, who devised for the Central-Hotel project a long building of four floors divided into three horizontal zones (Figure 1.6). With few vertical elements to draw the eye upward, lateral embellishments accentuated the building’s horizontal expanse. Rounded towers, each emblazoned with the name of the hotel, stood at the corners marking the longest side, which featured rich ornamentation, wrought-iron balustrades, and state-of-the-art plate glass windows. The transparency they afforded made the Central look more penetrable than the Kaiserhof, whose high ground-floor windows alternated with a heavy layer of rusticated mock-stone. On the upper floors of the Central, balconies and large windows helped integrate the building into the city outside, also in contrast to the Kaiserhof, which was set back on one side in the manner of a palace. The Central, conversely, presented itself as the northern gateway to the city’s premier commercial thoroughfare. Using its frontages to display the building’s overwhelming volume, the new hotel changed the visual profile of the surrounding neighborhood.

Figure 1.6 The Central-Hotel, 1879

The Central also brought the outside in, with the hotel’s Wintergarten concert house and adjacent banquet hall, restaurant, and café. The combination of luxury accommodation, fine dining, and nightly entertainment had never been tried in Berlin. The designation of so much space to show business and gastronomy, at the expense of intimate parlors and conversation spaces, added to the hotel’s profile as a place for short visits and quick pleasures, despite the availability of apartments upstairs. Movable screens and windows could integrate the Wintergarten, dining rooms, restaurant, and café into a visual whole. If the Kaiserhof had been a place for the bourgeois traveler to find privacy and peace, the Central provided stimulation and diversion.Footnote 62

Entertainments and technologies at the Central attracted attention from critics and journalists. The Central’s promise of steam heat (newsworthy in a city where people relied on coal ovens to warm individual rooms), advanced ventilation systems, generous numbers of toilets and baths, and such in-room amenities as sleeping nooks and built-in closets all signaled the capacity of the Central to provide the latest comforts. Critics touted it as “a hotel in the English and American style,” equal “in scale, splendor, and comfort” to the grand hotels of “London, New York, and Paris.” The “magnificent Wintergarten,” moreover, made the Central “one of a kind,” casting its “shadow over all things similar now in existence.”Footnote 63 Publicists interpreted the Central as a promising entry in the imaginary contest of whose capital had the best grand hotels.

Berlin welcomed six more grand hotels before 1900, all in the city center. Most of those properties not founded by corporations were acquired by them in short order. Each hotel struck its own balance between models: the Central, the archetypal Passantenhotel, oriented to business travelers, and the Kaiserhof, the urban Familienhotel, oriented to the leisured class. The second such Familienhotel to arrive was the Hotel Continental (1885), with its “noble, peaceful, and comfortable accommodations in the immediate vicinity of the Central Station,” wrote one reviewer.Footnote 64 When the hotel opened, the suites – full-fledged apartments, many with their own bathrooms and toilets – were the finest in Berlin. In private hands for its first five years, the Continental transferred to the Berlin Hotel Corporation, the Kaiserhof’s parent company, in 1890. In 1891, the Lindenhof (Unter den Linden Real Estate Corporation) presented a different approach, with a greater area devoted to public space at the expense of rooms, by incorporating a variety theater and 1,000-seat café. Next came the Bristol, opened the same year by the competing Hotel Management Corporation, owner of the Central. The Bristol would appeal to worldly travelers and local elites, who flocked to the hotel’s so-called American Bar. Two years later, in 1893, the Savoy distinguished itself with a sumptuously outfitted “conversation area” (Unterhaltungsbereich) intended for Berlin’s rich and powerful.Footnote 65 By the mid-1890s, a variegated, robust grand hotel scene had coalesced in the city center, offering fertile ground for the bourgeoisie’s pursuit of luxury.Footnote 66

The next wave of hotel building, in the early 1900s, occurred to the southwest of previous developments, around the Potsdam and Anhalt stations, in the direction of a new city center some three miles farther west. From the southeastern corner of the Tiergarten (Berlin’s central park), where Potsdamer Platz joined major east–west and north–south thoroughfares, there was easy access to the fashionable west, the city’s largest railroad stations, and its central districts. Finally, the area bordered Berlin’s most elite residences between the southern frontier of the Tiergarten and the northern bank of the Landwehr Canal. New grand hotels bridged the gap between this leafy quarter and the raucous economy of pleasure and leisure nearby: the myriad theaters, beer halls, restaurants, and shops of Potsdamer Platz and Leipziger Straße.Footnote 67 A cruising ground and sexual marketplace, this was also a zone of illicit pleasures.Footnote 68

Between 1898 and 1913, four grand hotels replaced many of the smaller hostelries in the neighborhood. Most of these new grand hotels followed the Kaiserhof model: rarified, quiet, and somewhat smaller than Passantenhotels such as the Central. The exception to this rule was the Excelsior, the largest hotel in Berlin to date, built across the street from Anhalt station between 1906 and 1908. Even bigger after a 1913 expansion, the property contained 550 guest rooms, cavernous public spaces, multiple restaurants, generous anterooms, and a sweeping ballroom.Footnote 69 Here was a Passantenhotel at its grandest, twice the size of the Central. Until 1945 the Excelsior remained the largest hotel in Germany, and possibly the largest on the European continent.Footnote 70

In contrast stood the Palast-Hotel, which had opened in 1893 with 100 rooms, 15 baths, a wine distributor, a banquet hall, a smoking room, and a restaurant. This intimacy was belied by the bombast of the facade, however, which faced two of Berlin’s most trafficked squares. As viewed from the apex of the V-shaped structure, the Palast-Hotel appeared in its promotional postcards to offer immediate access to the rush of Potsdamer Platz as it emptied into Budapester Straße. The Brandenburg Gate and Reichstag stood in the background, and off to the right peeked a corner of the octagonal expanse of Leipziger Platz.Footnote 71 Advertisements emphasized bustle and calm, centrality and retreat, conspicuousness and exclusivity – the best of all worlds.

Next came the Fürstenhof, facing the Palast at the bottleneck separating Potsdamer and Leipziger Platz and built in 1905–6 as an elaborate extension to an extant hostelry. The balconied facade, a baroque and Jugendstil pastiche, was the longest of all the city’s hotels so far (Figure 1.7). The ground floor contained several shops, two full-service restaurants, an automat diner, a café, and a cake shop, as well as the requisite common spaces: the ladies’ common area, smoking and writing rooms, and a garden court. Upstairs, the placement of closets on the hallway side of each of the hotel’s 300 guest rooms reduced sound, offered ample storage space for the personal possessions of longer-term residents, and provided a barrier between the private and public lives of hotel guests. Finally, and perhaps most appealingly, the Fürstenhof boasted the highly favorable guestroom-to-bathroom ratio of 3:1, boosting the hotel’s popularity among American tourists.Footnote 72 Yet Aschinger’s Incorporated (Aschinger’s Aktien-Gesellschaft), the corporation that built and owned the Fürstenhof as well as dozens of fast-food cafés for working-class Berliners, did not see a profit from this venture into elite commercial hospitality for at least a decade.

Figure 1.7 Promotional postcard for the Hotel Fürstenhof, ca. 1910

Aschinger’s annual reports provide uncommonly detailed accounts of how the corporation financed the construction of its first grand hotel, and it is in the details that the pitfalls of capital-intensive, speculative investment in early-twentieth-century Berlin become most clear.Footnote 73 Although the board blamed conservative trade policies and the burdens of a series of fiscal reforms, which fell heavily on the commercial sector, the corporation’s weakness was mostly a product of its foolhardy forays into the securities and real estate markets.Footnote 74

When Aschinger’s incorporated in 1900, its board used the influx of capital to raise even more capital through speculation on the stock exchanges. Scarcely a year later, in 1901, stock prices collapsed, and Aschinger’s lay exposed to serious risk.Footnote 75 The corporation now found itself having leveraged assets – stocks that had now lost much of their value – to make large investments in Berlin real estate for use as workers’ cafés, some of which took years to open. Moreover, revenues at existing cafés began to slip as early as 1901, when national rates of unemployment among industrial workers more than tripled and the purchasing power of that class diminished. Although joblessness declined in 1902, the rate of unemployment remained higher than it had been in 1900.Footnote 76 Still, Aschinger’s charged ahead in 1905 with plans to purchase the Leipziger Hof hotel and transform it into the city’s most luxurious hostelry to date.

The Fürstenhof hotel project nearly bankrupted the corporation. According to the board, “the multiple and incessant stoppages among the construction workers” at the site of the nascent hotel were to blame and had accounted for the eight-month delay in opening the premises to customers. The cost of stoppages notwithstanding, it is extraordinary that developers such as Aschinger’s, in an era of stormy labor relations, would be caught unawares by the objections of labor unions to having so many men work for so little pay on what was shaping up to be a veritable pleasure palace for the world’s elites. Even more extraordinary is that Aschinger’s fashioned a construction budget so tight that an eight-month delay could result in a 60 percent drop in profits when, in fact, the corporation’s main areas of revenue were not supposed to be the new hotel but rather, café concessions and rents on retail spaces throughout the city.Footnote 77 The managing directors had in effect robbed the corporation’s profitable enterprises in order to pay for their own imprudent speculation and real estate acquisitions dating back to 1901. They deflected criticism by shifting the blame to political adversaries, in this case the socialists and workers, a move some of the very same men would repeat after World War I. A longer-term problem for Aschinger’s was the competition, which intensified mere months into the Fürstenhof’s first year. The Adlon and Esplanade – on a per-bed basis, two of the most expensive hotels ever built – were ready for business almost as soon as the Fürstenhof welcomed its first guests.

The Adlon owed much of its resounding success to its location at the corner of Unter den Linden and Pariser Platz, next to the Academy of Art and steps from the British and French embassies, the Brandenburg Gate, and the Reichstag. For decades, the site had accommodated the Palais Redern, whose facade had been redesigned by Karl Friedrich Schinkel. When plans emerged for the destruction of the palace and its replacement with yet another grand hotel, a debate broke out in the city’s dailies. Eventually, however, the weight of opinion tipped in favor of the project, particularly after the emperor gave it public support.Footnote 78

So, a new building, largely financed on the credit of restaurateur and hotelier Lorenz Adlon himself, went up at this desirable address. (The property also incorporated the Hotel Reichshof, on a rear lot facing Wilhelmstraße.) Most of the building was five stories high, and it extended south and east from fronts on Pariser Platz and Unter den Linden respectively. The ground level sported rusticated stone around large arched bays. Above, half columns, generous windows, balconies of stone and iron, and relief sculptures graced the first through fourth stories. At the top, a sloping roof loomed behind an iron balustrade. The whole was sober and understated, in keeping with the clean lines of the Brandenburg Gate across the square and a classic, older Prusso-Hohenzollern commitment to austerity and restraint.Footnote 79

In degree and kind, the Adlon distinguished itself from all other grand hotels. It was indeed magnificent. A tamed rendition of the Louis XVI idiom reigned throughout, each element of interior design personally overseen by the famed furniture designers and interior decorators Wilhelm Kimbel and Anton Pössenbacher.Footnote 80 The interior palm garden, open all winter, balanced the ostentation of mosaic floors and a giant skylight with informal, low-slung wooden chairs. In the reception hall, simple furnishings and a white coffered ceiling mitigated the impact of a splendid staircase clad in bold carpet and colorful marble. In the American Bar, a heavy, dark ceiling presided over the simple, clean lines of wood panels and light parquet. And the Beethoven Parlor, with its ebony columns and heavy ornamentation, welcomed light by way of oversized French doors (Figure 1.8). The effect there and throughout was a harmonious, balanced whole.Footnote 81

Figure 1.8 The Beethoven Parlor at the Adlon, 1908

For privacy and quiet, rooms incorporated sleeping alcoves, a double set of doors, and concrete walls.Footnote 82 For hygiene and convenience, most rooms connected to private bathrooms of marble tile, porcelain amenities, and nickel fixtures (Figure 1.9).Footnote 83 For space and in the service of domesticity, apartments were available along the Unter den Linden front. With its well-appointed rooms, tasteful yet luxurious spaces, and prime location, the Adlon soon became the favorite of diplomats, royals, aristocrats, and American society mavens. The emperor himself frequented the establishment and chose to house his personal and state guests there. (The court paid a yearly fee for privileged access, which even His Majesty could not expect to enjoy for free.)Footnote 84 Louis Adlon capitalized on this association with the court by letting it be known that he had instructed his chef de reception to rent rooms to Germans only if they were of noble or royal blood.Footnote 85 It is doubtful he meant for that instruction to be heeded; the point was to advertise the Adlon’s exclusivity, which served to increase its popularity among titled and nontitled alike.

Figure 1.9 En suite bathroom at the Hotel Adlon, 1908

Yet even if the origins, ethos, and clientele of the grand hotels remained predominantly bourgeois, aristocrats had participated in the scene as guests, diners, and socializers since the beginning. And then in the twentieth century, aristocrats began to invest in hotels of their own. Shares in the German Hotel Corporation (Deutsche Hotel-Gesellschaft), which built the Esplanade between 1907 and 1908, were owned largely by members of such family lines as Hohenlohe, Fürstenberg, and Henckel-Donnersmarck.

The German Hotel Corporation conceived of, outfitted, and priced the Esplanade to appeal to the aristocracy and upper reaches of the commercial bourgeoisie, making it the city’s most exclusive hotel. Innovations for Berlin included the availability of handsome conference rooms for business travelers and elite Berliners, the use of electric bells for summoning servants, and the provision of a separate building for accommodating hotel staff. The designation of sixty rooms for household servants accompanying guests, moreover, endeared the Esplanade to the very wealthy and the landed.Footnote 86 The building materials themselves signaled riches: marble floors extended to many of the guest rooms, exotic woods clad the high walls, and oriental rugs muffled the footfalls of hundreds.Footnote 87 Like the Fürstenhof, the Esplanade had cost too much, but unlike Aschinger’s, the Esplanade’s owner, the German Hotel Corporation, had few other sources of revenue to support its adventure in commercial hospitality. The corporation went into partial receivership in 1913 and then liquidation in 1919.Footnote 88

Hotel Hierarchies

The public spaces, guest rooms, and guest lists of the Esplanade, the Adlon, and the other grand hotels dazzled contemporaries and can dazzle us still – blinding us, in effect, to these businesses’ important function as liberal institutions of class domination. Upstairs was a lavish and expensive show of free association among rational, well-behaved, well-dressed individuals of means. To stage it, architects, hotel owners, and managers directed that most of the stagehands, ropes, and winches be concealed in the wings, the loft, and under the stage itself. This is where the majority of people in the grand hotel could be found: in the dark, at their workstations. To keep these people in thrall, the managers forged and maintained elaborate hierarchies – interlocking chains of command that complemented the grand hotels’ architectural delineations of space, class, and power.

Grand hotel hierarchies had three genealogies: older modes of aristocratic authority over household workers, newer bourgeois distinctions between public and private, and the social relations of modern industrial techniques of exploitation. Hotel managers assembled these traditions into a model of efficiency and equilibrium that might counter the dangers of social heterogeneity in the hotels and the district surrounding them. As a project, the grand hotel illuminates another side of urban modernity. Behind the great new commercial enterprise stood a managerial class that by turns attempted to reproduce, refigure, and even concretize the power relations and distinctions among the classes.Footnote 89 In microcosm, Berlin’s grand hotels reveal nothing less than the architectural and managerial mechanisms of bourgeois power in urban, Imperial Germany.Footnote 90

Among managers and architects, the managerial class of Berlin’s grand hotels, certain tendencies emerged. First, managers and architects had a conciliatory relationship to the aristocracy. They sought and received honorary titles from royalty.Footnote 91 And like royalty, managers were transnational. They did stints all over Europe and beyond. These foreign sojourns, and the language skills they afforded, became necessary ingredients of a successful career.Footnote 92 Architects, too, traveled throughout Europe as part of their training. Both architects and managers read widely in foreign and international trade publications. Yet, managers and architects differed in their educational paths and in the social positions that those educations helped determine. Managers attended vocational high schools before accepting apprenticeships or internships. Their instruction was practical, practicality being a central value of the commercial bourgeoisie, the subclass to which managers belonged.Footnote 93 Architects, on the other hand, were members of the educated bourgeoisie (Bildungsbürgertum), and usually attended a classical high school (Gymnasium) before going on to earn certifications from such prestigious state architecture schools as the Berlin Bauakademie (Academy of Architecture).Footnote 94 The architects of Berlin’s first two grand hotels, Hude and Hennicke, attended the Bauakademie in the 1850s before co-founding their own firm in 1860.Footnote 95 To realize their creations, they regularly partnered with members of the commercial bourgeoisie. The fruits of such partnerships, grand hotels were a field in which the commercial and educated bourgeoisies collaborated. Inside these hotels, a general pattern, based on the fusion of operating principles of factories, armies, and great households, existed by the 1870s.

In his 1874 textbook for “hoteliers, architects, managers, and hotel company shareholders,” Guyer supplied a chart specifying ideal hierarchies for three different types of hotels: the “seasonal,” such as a seaside property, usually in “private” hands; the “year-round” hotel, such as the Kaiserhof, usually in the hands of a joint-stock company (Actienhotel); and the spa resort (Curetablissement), also corporate. Italicized letters in the chart connoted a particular office’s rank (Rangstufe), a term that harked to the organization of the military or the palace. A further level of distinction was that between “inner” and “outer” departments (départements). The outer comprised employees who dealt directly with outsiders (Fremden) – that is, guests and vendors. Hence, members of the outer department included porters, concierges, and waiters. The inner department contained everybody else: maids and maintenance workers, laundresses, cellar workers, and kitchen staff. On the management and maintenance of the hierarchies within each department, Guyer advised that regulations and distinctions of rank and role (Reglement and Dienstordnung) be “binding.”Footnote 96

The 1874 original and the revised, expanded edition of 1885 evinced the same understanding of hierarchy as fixed and nonnegotiable. The goal was a closed universe in which distinctions of rank, class, and gender were more solid than the outside world could achieve.Footnote 97 Labor agitation and intraclass animosities that so cleaved European societies outside should have little meaning in the hotel, where owners, architects, and managers had built the system and created the patterns by which it had to run. This hierarchy, based on the application of the productive division of labor to the enterprise of commercial hospitality, in theory was supposed to be unshakable.

The hierarchy depended upon the ability of hotel managers to oversee the actions and interactions of hotel workers. Indeed, Guyer went so far as to claim that the main role of the manager was to maintain “a total overview” of the business. His gaze should easily capture disciplinary infractions, according to a sample list of rules that encoded sharp distinctions of rank in dress, comportment, access to space, and rights. The rules circumscribed workers’ physical appearance (“Every employee should always be dressed neatly and appropriately to his station”), access to spaces (“Loitering in the staircases, corridors, in front of the hotel entrance, and particularly in the kitchen and cellar … is forbidden”), and personal liberty most generally (“Going out without special permission is prohibited”).Footnote 98 Guyer’s proscriptions distilled a familiar formula for social stratification by assembling men, women, and youths of all social levels under one roof, in one self-contained enterprise.

At the apex of the hotel hierarchy sat the owners (usually on a corporate board), the managing directors appointed by that board, and the individual hotel managers hired by those managing directors. Owners and managing directors were entrepreneurial men of property such as Lorenz Adlon or skilled businessmen such as Hans Lohnert (the managing director of Aschinger’s Incorporated). Managing directors at this corporate level oversaw managers of particular hotels. These on-site managers, in turn, oversaw the day-to-day operation of the business. The on-site manager served as the public face of the property, his name often gracing letterheads, brochures, and hotel menus.Footnote 99 Many of these managers received honors from the emperor, sharing them with the hotel itself in the form of the moniker Hoflieferant (purveyor to the court). Titles from other royal houses extended managers’ prestige still further. Moritz Matthäi of the Kaiserhof accepted from the King of Saxony the Knight’s Cross Second Class of the Order of Albrecht in 1899. Leopold Schwarz of the smaller Reichshof got the Order of the Siamese Crown from Prince Chakrabongse in 1906 for service to this personal guest of the German emperor.Footnote 100 Royal honors as a confirmation of status contributed to the health of a hotel’s business.Footnote 101 More effective than these honors, however, was a publicized personal friendship with the emperor himself. Only Lorenz Adlon enjoyed this distinction, and his hotel benefitted accordingly.

Distinctions mattered to individual hotel managers, many of whom before 1900 had risen from the ranks of the petty bourgeoisie, working class, or even peasantry. Emil Vollborth, for example, born in 1854, started as a waiter. He learned several languages, became a regular contributor to the trade publication Gasthofs-Gehilfen-Kalender (Hospitality Employees’ Digest), and published several booklets on gastronomy. He worked his way from waiter to headwaiter at hotels in Stettin and Pichelsdorf (near Berlin) before acquiring a building at Wilhelmstraße 44. There, Vollborth opened a hotel with thirty rooms and an apartment for himself, where he spent the rest of what appears to have been a comfortable, middle-class life.Footnote 102

Eduard Gutscher, one of the last to climb to the top, spent time at several intermediary rungs on the ladder before he could be master of the business. Stints as a waiter in London and Paris solidified his command of English and French. Once in Berlin, Gutscher persuaded the Hotel Bristol to take him on as a secretary in the manager’s office. In 1899, he moved up and over to the Palast-Hotel to be its chef de reception, one of the highest-ranking posts. Two years later, he stepped in as the hotel’s new manager and lessee. An erstwhile waiter from Graz, Gutscher now presided over 130 employees and enjoyed an annual income of 26,000 marks.Footnote 103

Those managers born after Gutscher, however, and coming of age in the early twentieth century, tended to come from the commercial bourgeoisie and thus started their careers with white-collar work. Max Dörhöfer, for example, was born to a hotelier and wine merchant in Rüdesheim am Rhein in 1883, attended vocational high school, completed a certificate program in hotel management, worked in white-collar positions across Europe and in Cairo, ran the family hotel business, and then assumed the position of manager for a world-famous hotel.Footnote 104 Dörhöfer’s trajectory is representative of this second generation of hotel managers who were born into the commercial middle class and were fitted for the work through formal, costly training.Footnote 105 Evidence of class mobility among hotel managers disappears for the period after 1900.

At the next level down stood restaurant managers. These men tended to rise from the rank of waiter to that of headwaiter. Andreas Nett’s career is typical. Born in the 1870s in Fürth, he traveled to London in 1895 to work as a waiter at the Langham Hotel, a position he held for two years.Footnote 106 Nett then assumed posts as sommelier in Paris and Switzerland.Footnote 107 He returned to service as a waiter shortly thereafter, this time in Bad Kreuznach and then Zurich.Footnote 108 Finally, in the 1900s, he attained the position of manager at the Café-Restaurant Bristol of the Hôtel de l’Europe in Munich.Footnote 109 A move to Berlin in the early 1910s resulted in a slight demotion: There, Nett worked for larger, more prestigious establishments but again as a waiter and headwaiter.Footnote 110 At two points, though, Nett managed to secure white-collar hotel work, first as a secretary at the Hôtel de la Ville de Paris in Strasbourg and then as an accountant at the Grand Nouvel Hôtel in Lyon.Footnote 111 Neither of these stints as a supervisor kept Nett from service for long, however, nor did they win him promotion to the higher managerial levels of the hotel hierarchy. Those posts were now reserved for Nett’s social betters, men who had never been waiters.

Waiters, nonetheless, occupied pride of place as the highest-ranked members of a hotel-restaurant’s service apparatus. While their earnings were on a par, waiters maintained strict hierarchical distinctions among themselves. At the top stood the headwaiters (Oberkellner). These were always men, normally without children. Their pay and their hours discouraged the establishment of a family, and employers avoided hiring and retaining family men. Job advertisements requested that a prospective headwaiter be single, as well as “presentable, solvent, experienced, and conscientious.”Footnote 112

Below these masters of service and next in the chain of command were the staff waiters. Like the headwaiter, staff waiters had to have a command of European languages. “Perfect” French and English were a must. And only well-turned-out men needed apply. Next came the sommeliers, and then the floor waiters (Etagenkellner), who assisted the headwaiter. Floor waiters and sommeliers were not necessarily novices. Job advertisements stressed that they should have had experience in one of the “bigger houses” before taking on work at one of Berlin’s grand hotels.Footnote 113 Another category of server, room waiters (Zimmerkellner), fell under the supervision of the floor waiters and provided what we now call room service. With some experience, room waiters tended to be younger than their bosses, the floor waiters, and strived for promotion.

Neophytes crowded the lowest level of the wait staff. These were the apprentices, teenage boys, often unpaid, who rendered their unskilled services for anywhere from six months to two years. These boys did most of the manual work, delivering and clearing china and glassware, disposing of detritus, assembling trays, and performing any and all other services that headwaiters, staff waiters, floor waiters, and sommeliers required. For these boys especially, but for almost everyone working for the gastronomy concessions, hotel service was physically demanding and poorly remunerated, yet it was also a career that held many advantages over factory work and domestic service. For one thing, it allowed some chance of advancement, which factory work and domestic service often precluded.

Hotel service could also pay better than factory and domestic work. At the finest establishments, such as a restaurant specializing in fine wines (Weinhaus) in Friedrichstadt around 1910, a waiter could expect to earn 15 marks per month. Tips augmented this income at rates of 10 percent of the bill for exceptional service and petty change in most other cases.Footnote 114 (A waiter thus earned between 1 percent and 3 percent of the salary of a corporate managing director, who took home 50,000 marks per year in the years around 1910.Footnote 115) Waiters used their tips to cover regular deductions: a monthly 10 pfennigs for the dishwasher, 30 pfennigs for the cloakroom staff. There were also punitive deductions – one-half of 1 percent of a month’s wages for each broken glass, for example – and further financial penalties for lateness or other minor infractions.Footnote 116 Yet, becoming a waiter represented an improvement for many career hopefuls, usually born into the peasant or working classes. Fritz Haas, for example, born in Linz around 1860, son of a stonemason, began as a waiter’s apprentice and moved up to the position of waiter, a post he held for the rest of his working life.Footnote 117

For white-collar workers, upward mobility was swifter and easier.Footnote 118 Their tier in the hierarchy offered several managerial positions into which a hard-working and lucky secretary could infiltrate. The highest position under the hotel manager was the chef de reception. In many cases, this post was preparation for the assumption of the post of manager. The chef de reception oversaw bookings and enjoyed direct contact with the hotel’s most distinguished guests. He was a master of customer service, enabled by a command of European languages, and carried his responsibilities with an easy dignity that signaled a grand hotel’s uprightness and elegance.Footnote 119 Chefs de reception could earn a good deal of money. The Bristol’s Robert Gonné took home 4,200 marks per year in the early twentieth century.Footnote 120 Clerks, other accountants and bookkeepers, and lower-level managers of the kitchens and cellars came next. Finally, there were female office workers and female members of the lower managerial staff, who earned little more than waiters and occupied the lowest level of the white-collar hierarchy.

But many people working in the hotel were not of the hotel. Corporations leased several of their concessions to sole proprietors (Pachtträger). These were the ticket, flower, and cigar sellers, barbers and hairdressers, barkeeps, café owners, automat supervisors, porters, and cloakroom managers. Cloakrooms were typically leased to women. Martha Windisch held the cloakroom concession at the Fürstenhof at a monthly cost of about 830 marks in 1913. With it, she earned enough money to pay for an apartment in the fashionable west, on Lützowstraße. Windisch’s lease required that her cloakroom attendants, girls visible behind a window in the vestibule, be representatives of the hotel, even if they were not its employees. “Politeness” and “courtesy” were essential. “Only personnel of handsome and clean appearance” would do. Moreover, these hirelings had to be women, wear a uniform, respond to guests’ wishes, demand no tips, and above all, respect their “social betters,” as the lease put it.Footnote 121 In such terms, the Fürstenhof and its parent company, Aschinger’s Incorporated, maintained control over the cloakroom personnel. Yet at the same time, the corporation could claim a steady income from the cloakroom while outsourcing the risks and responsibilities of daily operation.

Like cloakroom girls, porters and pages often worked for a sole proprietor lessee, usually the head porter, who employed more than a dozen boys to do the heavy lifting. They wore uniforms and were bound to the house rules of politeness and deference. Boys as young as twelve, and in rare cases younger than that, donned militaristic garb and took orders. While guests were checking in at reception, these boys ticketed the luggage and loaded it onto a hydraulic lift that went down, not up. In the cellar, more porters sorted the cases and waited for instructions from the reception desk. Page boys delivered these instructions on tickets that included guests’ room numbers and a code or color that matched that of the guest’s luggage tag (Figure 1.10). On finding a match, a porter would take the cases in hand and haul them onto a service elevator. At the right floor, another porter would be waiting to take the luggage and rush it to the room of its owner. All this was supposed to happen ahead of the owner’s arrival upstairs. Tips were de rigueur but collected in full by the head porter, who first covered his own costs and then distributed the surplus to his staff.

Figure 1.10 Page boys at the Elite Hotel, a midsize luxury hostelry in Berlin, ca. 1910

Next came the servants, who acted as personal butlers to several masters at once. Responsible for packing, unpacking, and connecting guests to other concessions in the hotel, servants often delegated tasks to more specialized providers such as floor waiters, messengers, shoe shiners, hairdressers, barbers, seamstresses, and laundresses.Footnote 122 Servants tended to be men, and many had been porters or pages first. Most were still young. Only a few women served in this capacity, normally as hired ladies’ maids.

Toward the bottom of the hierarchy were the parlor maids, all women. In their late teens and twenties, they worked directly under female housekeepers, the lowest managerial level. These housekeepers earned as much as 60 marks per month, whereas parlor maids could expect 12 to 15 marks and the rare tip.Footnote 123 They cleaned rooms, hallways, public spaces, and the servants’ areas in the cellar and attic. Like most lower hotel workers, parlor maids slept and ate on the premises and got a half day off every other week.Footnote 124 In this way, the life of a parlor maid in one of Berlin’s grand hotels resembled that of a parlor maid in a bourgeois household.Footnote 125

Still more women and girls found employ below stairs alongside skilled and unskilled male counterparts (Figures 1.11, 1.12, 1.13, and 1.14). Women cleaned dishes, polished silver, and did laundry with the aid of machinery that increased the speed of work. Slated for the most menial tasks, still more women served as kitchen maids and maids of all work. They labored among better paid men such as engineers, carpenters, furnace stokers (Figure 1.14), and haulers.Footnote 126

Figure 1.11 Women and men at work in the cellar of the Hotel Esplanade, ca. 1915

Figure 1.12 Cooks in the main kitchen of the Esplanade, one of the first cellar kitchens in a Berlin hotel to feature mechanical ventilation, ca. 1915

Figure 1.13 Pastry cooks and a sugar sculptor in the Esplanade patisserie, ca. 1915

Figure 1.14 Furnace stoker at the Esplanade, ca. 1915