A Introduction

In the past two decades, the rapid development of the Internet allowed the growth of e-commerce, and together with the new digital technologies and the Internet of Things, the flow of data – both commercial and personal has increased to levels unseen before. Traditional trade rules could serve as a starting point to deal with these issues but they clearly are not enough. To provide some context, in 1994 – at the time the World Trade Organization (WTO) and its agreements were established by the Marrakesh Agreement – Mosaic was the most used web browser on the Internet. (Netscape Navigator was created the same year, and Internet Explorer was only released in 1995.)Footnote 1 Neither Google, nor Amazon or Facebook existed in 1994. The ‘modern’ rules of trade law were not designed having taken into account the characteristics of contemporary digital trade and data flows.

This situation has led to the regulation of electronic commerce today becoming one of the most important topics in trade law and policy. Efforts of dealing with these issues at a multilateral level started in 1998, when the WTO established a work programme on electronic commerce and at the ministerial conference that same year, members agreed on a temporary duty-free moratorium on all electronic transactions – a practice that since then has been renewed at each WTO ministerial conference.Footnote 2 Further development has been slow paced and we are still far from achieving consensus on this topic. Only in December 2017, forty-four WTO members made a joint declaration to initiate exploratory work together toward future negotiations on trade-related aspects of electronic commerce.Footnote 3 In 2019, some countries like India and South Africa argued that the e-commerce moratorium in the WTO led to loss of revenue, as it gave such transmissions immunity from taxation, and initially opposed to the renewal of the duty-free moratorium.Footnote 4 And while there has been a new reinvigoration under the 2019 Joint Statement Initiative with currently seventy-seven WTO members on board, overall, until now, the WTO has made no substantive progress on e-commerce, and countries have not been able to agree on a multilateral regime for the treatment of e-commerce and data flows.Footnote 5

But the lack of consensus at a multilateral level does not mean that rules for digital trade are not being created elsewhere. In fact, since the beginning of the twenty-first century, certain countries have been including provisions and even chapters on electronic commerce, as well as rules on data flows, in preferential trade agreements (PTAs). It is well known that the United States has been important in the creation and diffusion of digital trade rules, especially after the 2002 US Digital Trade Agenda and the Bipartisan Trade Promotion Authority Act of the same year.Footnote 6 Not so well known is the relevant role other actors have played in the development of these rules.Footnote 7 This contribution focuses on one group of countries of the Latin American region, which have been the most important vectors of the inclusion of e-commerce and data rules in PTAs – a group that includes Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Peru, and Panama. For the purpose of this chapter, we consider ‘Latin American’ PTAs those trade agreements in which at least one, or more parties, is a country from Latin America and the Caribbean region.

Besides highlighting the contribution that those countries have had in the creation and diffusion of this new rule-making, our goal is also to determine the level of regulatory convergence that Latin American countries (LACs) have on rules on digital trade and data flows. For this purpose, we understand regulatory convergence as an overarching notion that aims to reduce unnecessary regulatory incompatibilities between countries in a dynamic and incomplete process.Footnote 8 The rationale behind regulatory convergence in PTAs stems from the idea that regulatory diversity may entail significant costs that can hinder cross-border exchanges,Footnote 9 and that the maintenance of needlessly burdensome cross-border differences in regulation can result in a number of additional negative policy impacts, including higher transaction costs stemming from information asymmetries.Footnote 10 Divergent regulatory requirements can lead to duplication of procedures and costs in trade that are important for all internationally active businesses and especially so for small- or medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), for which such fixed costs can be a deciding factor in whether or not to export or invest, including across borders.Footnote 11 Lack of transparency or clarity of regulations, as well as excessive, inefficient, or ineffective regulations, create unnecessary delays or impose costs on traders and investors.Footnote 12

Regulatory convergence mechanisms include substantive or procedural aspects that are aimed at two different types of regulatory outcomes. In some agreements, regulatory convergence aims to achieve substantive regulatory harmonisation (similar or equivalent regulation – ‘substantive convergence’). Other agreements consider harmonisation of the processes by which regulations are developed, adopted, publicised, and implemented (similar or equivalent procedures – ‘procedural convergence’). With different denominations,Footnote 13 both approaches are present in the PTAs examined in this chapter.

The chapter is organised as follows. After the introduction, we provide a detailed description of e-commerce and data rules found in Latin American PTAs, and their convergence or divergence. Then we briefly present the domestic frameworks of relevant LACs on digital trade–related topics, as well as their consistency with existing international commitments, with special emphasis on personal data protection. To conclude, we highlight some potential conflicts that could arise between these countries’ domestic regulations and international commitments in the field.

B Regulatory Convergence in E-Commerce and Data Flow Provisions in Latin American PTAs

The inclusion of provisions in PTAs referring explicitly to e-commerce and data flows is not a recent phenomenon, although it has evolved importantly in the past two decades. According to the TAPED dataset, 191 PTAs include provisions that are related to e-commerce and data flows, with 116 PTAs with e-commerce provisions and 86 with e-commerce chapters.Footnote 14 These provisions are highly heterogeneous and address various issues including customs duties and non-discriminatory treatment of digital products, electronic signatures, paperless trading, unsolicited electronic messages, as well as consumer protection, data protection, data flows, and data localisation.

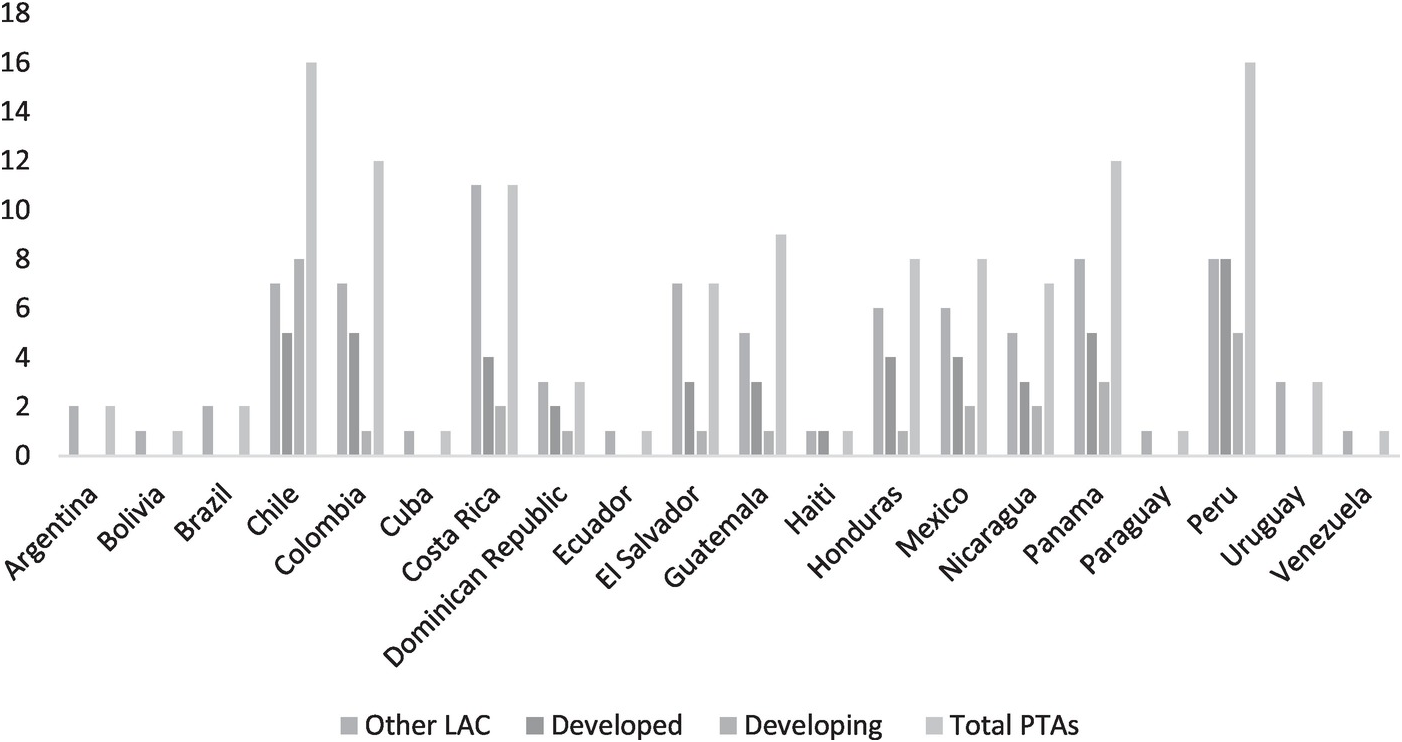

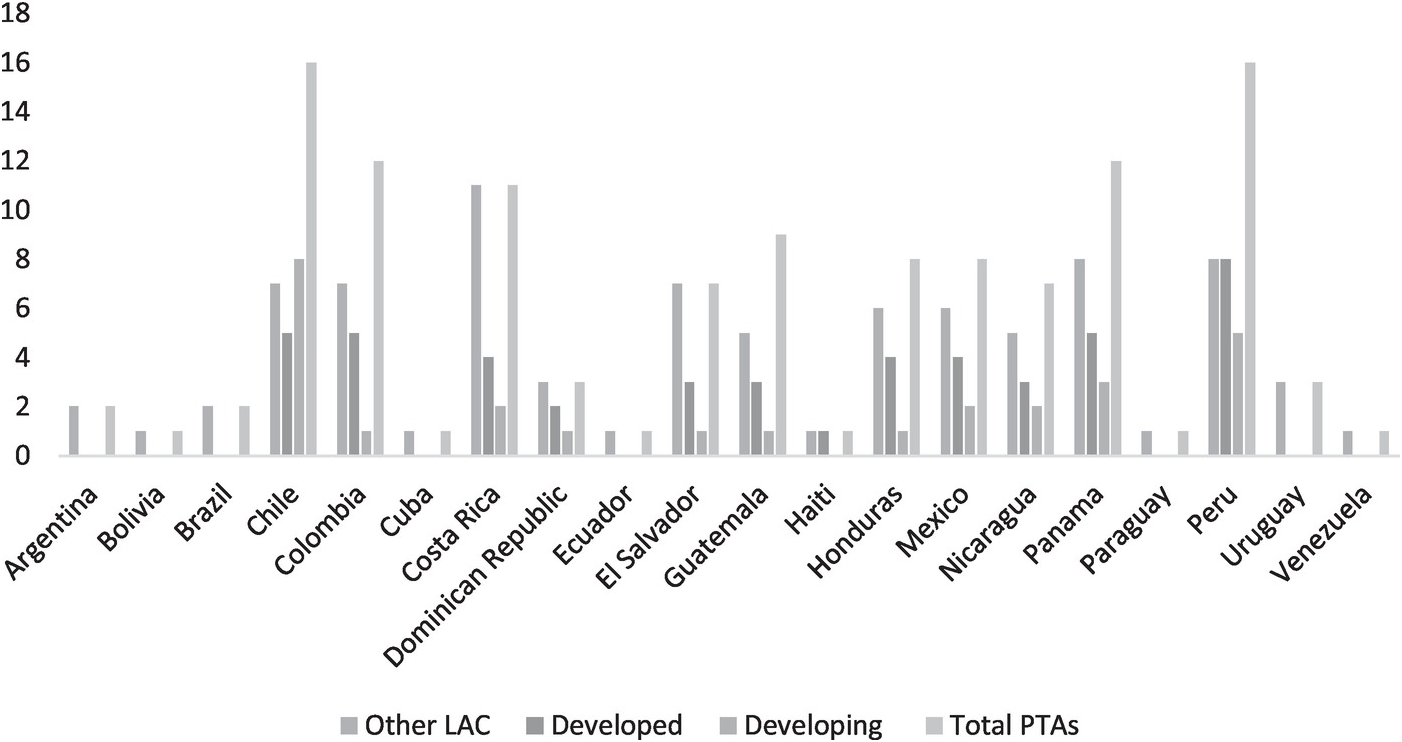

As detailed in Table 13.1, of the total number of PTAs with e-commerce and data flow provisions the countries of Latin America have concluded 53 per cent (62 agreements, 47 chapters). Twenty-nine of these agreements have been concluded with developed countries (47 per cent of this subset) and 33 with other developing countries (53 per cent of this subset), most of them also from Latin America (26 agreements in total). The countries leading this treaty-making practice in the region are Chile (18 PTAs) Peru (16 PTAs), Colombia (12 PTAs), Panama and Costa Rica (11 PTAs each). This is in line with the fact that the surge of PTAs having e-commerce provisions involves both developed and developing countries. 49 per cent of the PTAs with e-commerce provisions were negotiated between developed and developing countries, and 47 per cent were negotiated between developing countries.Footnote 15

Table 13.1. Latin American PTAs with e-commerce or data flow provisions

| Country | Other LACs | Developed | Developing | Total PTAs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Bolivia | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Brazil | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Chile | 7 | 5 | 8 | 16 |

| Colombia | 7 | 5 | 1 | 12 |

| Cuba | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Costa Rica | 11 | 4 | 2 | 11 |

| Dominican Republic | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Ecuador | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| El Salvador | 7 | 3 | 1 | 7 |

| Guatemala | 5 | 3 | 1 | 9 |

| Haiti | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Honduras | 6 | 4 | 1 | 8 |

| Mexico | 6 | 5 | 2 | 9 |

| Nicaragua | 5 | 3 | 2 | 7 |

| Panama | 8 | 5 | 3 | 12 |

| Paraguay | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Peru | 8 | 8 | 5 | 16 |

| Uruguay | 3 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Venezuela | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

The earliest e-commerce provision in a PTA involving a Latin American country is found in the 2001 Canada–Costa Rica Free Trade Agreement (FTA), which included a Joint Statement on Global Electronic Commerce. In a non-binding fashion, it addresses several issues, like the applicability of WTO rules to e-commerce, supporting industry developments in the field, stakeholder’s participation, transparency, and consumer and data protection. In 2002, the Chile–EU Association Agreement properly included e-commerce provisions in the text of the treaty on issues such as cooperation and data protection.Footnote 16 The first PTA concluded in the region having a dedicated e-commerce chapter is the 2002 Chile–US FTA. In 2006, the Nicaragua–Taiwan FTA began the inclusion of provisions on data flows as part of its cooperation commitments. The number of Latin American PTAs with such provisions has increased over the years (see Figure 13.1), simultaneously with the growing discussions on the digital economy and its move up as a topic on the policy agendas and negotiation tables.

Figure 13.1. Latin American PTAs with e-commerce and data flow provisions

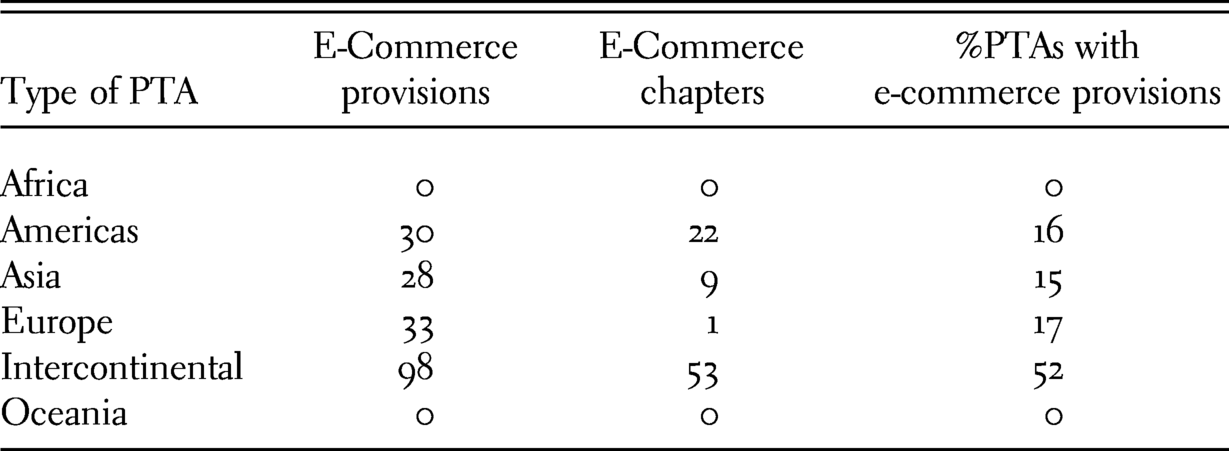

Although the number of PTAs with e-commerce and data flow provisions remains limited, the last eight years have shown a significant increase in the number of agreements with such provisions. Overall, agreements including such provisions are mainly of an intercontinental nature, but around one-third of these PTAs have at least one Latin American country as a contracting party (thirty-one treaties) and Latin America is one of the most relevant regional area with this type of treaty-making (Table 13.2).

Table 13.2. PTAs concluded with e-commerce provisions per region

| Type of PTA | E-Commerce provisions | E-Commerce chapters | %PTAs with e-commerce provisions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Americas | 30 | 22 | 16 |

| Asia | 28 | 9 | 15 |

| Europe | 33 | 1 | 17 |

| Intercontinental | 98 | 53 | 52 |

| Oceania | 0 | 0 | 0 |

PTAs with e-commerce provisions involving LACs have also increased their level of detail significantly over the years. Seven is the average number of PTA provisions found on e-commerce chapters in the past five years, with an average of 955 words. A treaty involving a Latin American country, the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA), is currently the PTA in force with the largest number of articles and words on e-commerce, as its current text has 19 articles and an average of 3,206 words. Several PTAs having a Latin American country as a party have devoted more than 11 articles and 1,900 words to these topics, like the 2017 Argentina–Chile FTA, the 2015 Pacific Alliance Additional Protocol (PAAP), the 2016 Chile–Uruguay FTA, the 2018 Australia–Peru FTA, the 2018 Brazil–Chile FTA, and both the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPP) and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), whose e-commerce chapter reiterates verbatim the TPP text.

C E-Commerce and Data Provisions in Latin American PTAs

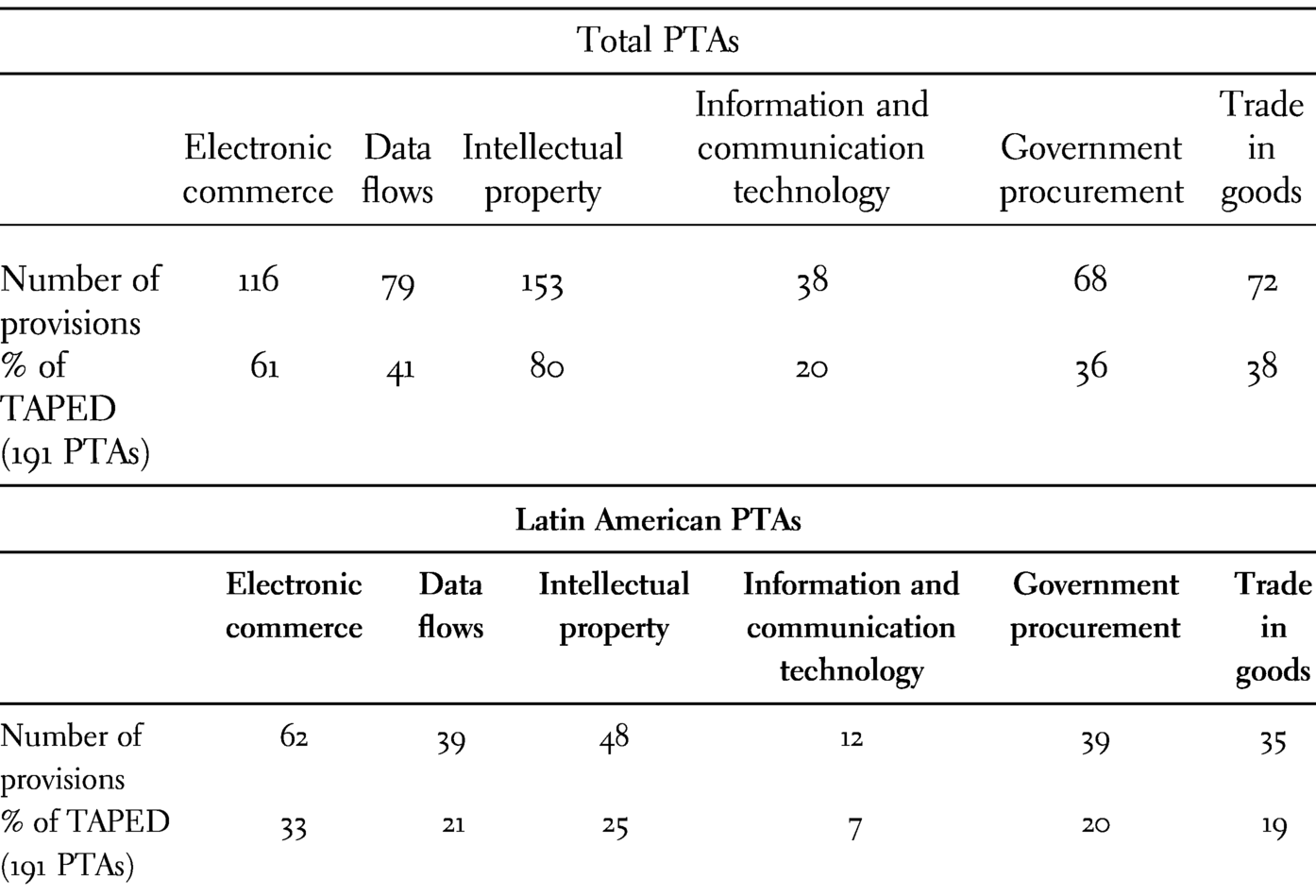

E-commerce and data provisions are found in the main text of several Latin American PTAs, mostly on chapters or sections dedicated to e-commerce or intellectual property (IP). When available, data flow provisions are also found in these chapters or sections, but are commonly included in chapters on specific services, mainly telecommunication and financial services. E-commerce provisions can also be found in side documents, like annexes, joint statements, and side letters. As presented in Table 13.3, Latin American PTAs represent an important number of treaties with such provisions.

Table 13.3. Total PTAs and Latin American PTAs with e-commerce and data flow provisions

| Total PTAs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic commerce | Data flows | Intellectual property | Information and communication technology | Government procurement | Trade in goods | |

| Number of provisions | 116 | 79 | 153 | 38 | 68 | 72 |

| % of TAPED (191 PTAs) | 61 | 41 | 80 | 20 | 36 | 38 |

| Latin American PTAs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic commerce | Data flows | Intellectual property | Information and communication technology | Government procurement | Trade in goods | |

| Number of provisions | 62 | 39 | 48 | 12 | 39 | 35 |

| % of TAPED (191 PTAs) | 33 | 21 | 25 | 7 | 20 | 19 |

In the following sections, we examine the provisions of Latin American PTAs in two main groups: (i) electronic commerce and (ii) cross-border data flows.

An assessment of the extent of legalisation of these provisions was also performed, distinguishing between ‘soft’, ‘mixed’, and ‘hard’ commitments. We considered as ‘soft’ those commitments that are not enforceable by the parties, like ‘best efforts’ and cooperation commitments. We classified as ‘hard’ those commitments that oblige a party to comply with a rule or a principle and which are enforceable by another party. Finally, we consider an agreement with ‘mixed’ legalisation if the treaty has both soft and hard commitments. Similarly, we included in this category references to other agreements that are only partially applicable.Footnote 17

I Electronic Commerce

1 Objectives and Principles

Several Latin American PTAs with e-commerce chapters converge on explicitly stating a number of objectives like avoiding unnecessary barriers to e-commerce (37 PTAs), addressing the needs of SMEs (31 PTAs), promoting and facilitating its use (both between the parties and globally (30 PTAs), considering private participation in the development of the regulatory framework for e-commerce (15 PTAs), and the principle of technological neutrality (15 PTAs).Footnote 18 The first three objectives and principles are also commonly found in PTAs with e-commerce chapters concluded by countries outside of Latin America.

2 Applicability of WTO Rules

Although all Latin American countries that have concluded PTAs with e-commerce or data flow provisions are members of the WTO that does not necessarily mean that these countries consider that WTO law applies to digital trade. In fact, only one-third of Latin American PTAs include provisions on the applicability of WTO rules to e-commerce – twenty agreements from a total of sixty-two PTAs – with important differences of language across agreements. The first treaty including such provisions is the 2001 Canada–Costa Rica FTA, which only makes a reference to the maintenance of the WTO practice of not imposing customs duties on electronic transmissions between the parties.Footnote 19 Some treaties explicitly recognise the applicability of the WTO rules to electronic commerce, but without clearly specifying which the applicable provisions would be.Footnote 20 Certain agreements clarify the application of WTO rules to e-commerce ‘to the extent they affect electronic commerce’,Footnote 21 or to measures ‘affecting electronic commerce’.Footnote 22 In other softer variations, countries merely reaffirm their respective commitments under WTO agreements in the respective e-commerce chapter/section.Footnote 23

3 National Treatment (NT) and Most-Favoured Nation (MFN) Obligations

The number of Latin American agreements including provisions with explicit commitments on non-discrimination on digital trade is relatively small. In the TAPED dataset, eighteen PTAs include MFN commitments to give a treatment no less favourable on e-commerce to parties to the treaty than they accord to non-parties; and nineteen PTAs consider NT commitments to give a treatment no less favourable to other parties to the treaty than they accord domestically on e-commerce. In contrast, in the whole TAPED dataset we find thirty-five PTAs with NT and thirty-two with MFN provisions.

The large majority of these provisions are binding.Footnote 24 Following the 2015 Pacific Alliance Additional Protocol (PAAP), some agreements consider NT and MFN together, as part of a general commitment to non-discriminatory treatment of digital products. According to this provision, no party shall accord less favourable treatment to digital products created, produced, published, contracted for, commissioned or first made available on commercial terms in the territory of another party or to digital products of which the author, performer, producer, developer, or owner is a person of another party than it accords to other like digital products.Footnote 25 In certain treaties, a footnote further clarifies that to the extent that a digital product of a non-party is a ‘like digital product’, it will qualify as an ‘other like digital product’.Footnote 26

But the majority of Latin American PTAs consider separate paragraphs for NT and MFN. On national treatment, the most common wording goes back to the 2006 Panama–Singapore FTA, which stipulates that a party

shall not accord less favourable treatment to some digital products than it accords to other like digital products, on the basis that the digital products receiving less favourable treatment are created, produced, published, stored, transmitted, contracted for, commissioned or first made available on commercial terms outside its territory; or the author, performer, producer, developer or distributor is a person of another Party or a non-Party; or so as otherwise to afford protection to other like digital products that are created, produced, published, stored, transmitted, contracted for, commissioned, or first made available on commercial terms in its territory.Footnote 27

A variation of this provision uses ‘may’ instead of ‘shall’, theoretically making the commitment less binding.Footnote 28 Another variation narrows the NT as it only applies to the digitally delivered products associated with the territory of the other party or where the author, performer, producer, developer, or distributor is a person of the other party.Footnote 29 A simpler recognition of NT is found in the Canada–Peru FTA, where the parties merely confirm the application of national treatment for goods to trade conducted by electronic means.Footnote 30

Regarding MFN, some agreements stipulate that a party

shall not accord less favourable treatment to digital products created, produced, published, stored, transmitted, contracted for, commissioned or first made commercially available in the territory of another Party, than it accords to like digital products in the territory of a non-Party. Furthermore, a Party shall not accord less favourable treatment to digital products of which the author, performer, producer, developer or distributor is a person of a non-Party.Footnote 31

A variation of this provision uses ‘may’ instead of ‘shall’, making the commitment less binding.Footnote 32

4 Customs Duties

One of the most common provisions found in PTAs regarding digital trade (eighty-four PTAs in TAPED) is the commitment to not impose customs duties on digital products. Wu points out that this type of provision facilitates commerce in downloadable products, such as software, e-books, music, movies, and other digital media.Footnote 33 Despite being commonplace, these commitments have different wording in how the obligation is drafted. From the thirty-nine Latin American PTAs that include such provision, some agreements merely reaffirm the WTO member’s practice of not imposing customs duties on electronic transmissions,Footnote 34 rather than seeking to expand it towards a WTO-plus obligation. However, the most common approach is a provision including a permanent moratorium on duty-free treatment in the PTA, meaning that no customs duties should be imposed on electronic transmissions and digital products. Yet again, this second type of provision has several variations.

Some agreements plainly stipulate that a party may not apply customs duties on digital products of the other party,Footnote 35 or in more binding terms that it ‘shall not’ impose customs duties on electronic transmissions,Footnote 36 or not apply customs duties, fees, or charges on import or export by electronic means of digital products.Footnote 37 In certain agreements, the parties agree that electronic transmissions shall be considered as the provision of services, which cannot be subject to customs duties.Footnote 38 In other treaties, the parties simply agree not to impose duties on ‘deliveries by electronic means’.Footnote 39

Only a couple of agreements consider this obligation regardless whether the digital products in question are fixed on a carrier medium or transmitted electronically.Footnote 40 In several of these treaties there is an explicit distinction between digital products which are transmitted by electronic means and those whose sale occurs online but who are physically transported over the border. According to these PTAs a party shall not apply customs duties on digital products by electronic transmission, but when these are transmitted physically, the customs value is only limited to the value of the carrier medium and does not include the value of the digital product stored on the carrier medium.Footnote 41 A variation of this provision, usually found in agreements concluded with the United States, uses ‘may’ instead of ‘shall’, theoretically making the commitment less binding.Footnote 42 Certain Latin American PTAs explicitly mention that the moratorium does not extend to internal taxes or other charges. The wording of this exclusion varies across treaties. While some do not prevent a party from imposing an internal tax or charge to digital products delivered or transmitted electronically,Footnote 43 others exclude products imported/exported by electronic transmissions or means,Footnote 44 or content transmitted electronically between a person of one party and a person of the other party.Footnote 45

5 Electronic Authentication

Thirty-seven Latin American PTAs include provisions on electronic authentication, which represent around half of the overall universe of PTAs having these provisions. Typically, they allow authentication technologies and mutual recognition of digital certificates and signatures. While earlier treaties included only best efforts commitments in this field, recent agreements include more binding and mandatory clauses. Fifty per cent of all PTAs including such provisions have been concluded by Latin American countries.

We find the earliest example of soft commitments on electronic authentication back in 2001, when Canada and Costa Rica merely acknowledged the necessity of policies to facilitate the use of technologies for authentication and for the conduct of secure e-commerce.Footnote 46 Other agreements included only cooperation commitments on electronic authentication. These comprise activities to share information and experiences on laws, regulations, and programmes on electronic signaturesFootnote 47 or secure electronic authentication;Footnote 48 and to ‘maintain a dialogue’ on the facilitation of cross-border certification services,Footnote 49 or digital accreditation.Footnote 50

More binding commitments on authentication and digital certificates establish restrictions on legislation, using both negative and positive obligations. According to a first group of agreements, no party may adopt or maintain legislation that (i) prevents or prohibits parties from having the opportunity to prove in court that their electronic transaction complies with any legal requirements with respect to authentication;Footnote 51 or (ii) prohibits parties to an electronic transaction from mutually determining the appropriate authentication methods.Footnote 52 Some of these treaties consider this obligation in more binding terms (‘no Party shall adopt or maintain’).Footnote 53 In a second group of agreements, each party has the positive obligation (‘each Party shall adopt or maintain’) of having domestic legislation for electronic authentication that permits parties to electronic transactions to (i) determine the appropriate authentication technologies and implementation models for their electronic transactions, without limiting the recognition of such technologies and implementation models; and (ii) to have the opportunity to prove in court that their electronic transactions comply with any legal requirements.Footnote 54

Further commitments on electronic signatures establish that neither party may deny the legal validity of a signature solely on the basis that it is in electronic form, either in negative (‘may not maintain’)Footnote 55 or positive terms (‘a Party shall not deny’).Footnote 56 Some agreements include exceptions to these commitments, considering that a party may require that the electronic signatures be certified by an authority or a supplier of certification services accredited under the party’s law or regulations for a particular category of transactions or communications.Footnote 57 In certain cases, it is stipulated that such requirements shall be objective, transparent, and non-discriminatory and relate only to the specific characteristics of the category of transactions concerned.Footnote 58 In other agreements, it is considered that a party may deny the legal validity of an electronic signature under circumstances provided for in its law.Footnote 59

Additional commitments on electronic authentication refer to the recognition of digital certificates, either publicly or privately issued. On public authentication, some agreements consider working towards the recognition of such certificates at a government level, based on internationally accepted standards,Footnote 60 on cooperation mechanisms between the respective national accreditation and digital certification authorities for electronic transactions,Footnote 61 or by mutual recognition agreements on digital/electronic signature.Footnote 62 On private authentication, certain treaties encourage the use of interoperable electronic trust or authentication,Footnote 63 digital certificates in the business sector,Footnote 64 and advanced or qualified certificates.Footnote 65 For that purpose, parties may endeavour to facilitate the procedure of accreditation or recognition of suppliers of certification services.Footnote 66

6 Source Code

Overall, few PTAs include provisions referring to source code (sixteen treaties), but one third of them are concluded by Latin American countries. These clauses are largely binding prohibitions to require the transfer or access to proprietary source code of software, as a condition for the import, distribution, sale, or use of such software.Footnote 67

In the CPTPP, the parties commit to not requiring the transfer of, or access to, source code of software owned by a person of another party, as a condition for the import, distribution, sale, or use of such software, or of products containing such software, in its territory. For these purposes, software is limited to mass market software or products containing such software, and does not include software used for critical infrastructure. However, some exceptions are considered in the same agreement, like the inclusion or implementation of terms and conditions related to the provision of source code in commercially negotiated contracts; a modification of source code necessary for a software to comply with domestic laws or regulations; and requirements that relate to patent applications or granted patents, including any orders made by a judicial authority in relation to patent disputes, subject to safeguards against unauthorised disclosure under the law or practice of a party.Footnote 68

Later treaties have largely followed the CPTPP wording on this topic.Footnote 69 An important variation is found in the USMCA, where the protection given to source code also extends to algorithms expressed in a source code. The agreement includes a broad definition of ‘algorithm’, which is understood as ‘a defined sequence of steps, taken to solve a problem or obtain a result’.Footnote 70 Most importantly, the USMCA considers few exceptions to the protection of source code and related algorithms, being limited to the requirements made by a regulatory body or judicial authority for a specific investigation, inspection, examination enforcement action, or judicial proceeding, subject to safeguards against unauthorised disclosure. Such disclosure shall not be construed to negatively affect software source code’s status as a trade secret, if such a status is claimed by the owner. DEPA also deals with algorithms but concerning products that use cryptography and are designed for commercial applications.Footnote 71

7 Personal Data

The protection of personal data in e-commerce or digital trade chapters of Latin American PTAs usually takes two distinctive paths: while one group of provisions deals with it from the point of view of the protection of privacy as a fundamental right (whether or how data is shared, collected, or stored, and regulatory restrictions), another group of provisions regulates the protection of such data as consumer rights. When included, agreements tend to have both privacy and consumers rights provisions, although with different levels of commitment across treaties. Both consumer protection and privacy rules are similar but different takes on the same issue. As we will see, the most binding provisions are related to privacy and not to consumer protection per se.

Few agreements, but increasing in number in recent years, explicitly exclude from the e-commerce chapter the information held or processed by or on behalf of a party or measures related to such information, including measures related to its collection.Footnote 72 These provisions put states in an asymmetrical position vis-à-vis international traders and investors, as they exclude governmental data collection and processing from the disciplines dealing with the treatment of personal data. Around half of all PTAs having these provisions have been concluded by Latin American countries (Table 13.4).

Table 13.4. Personal data provisions in Latin American PTAs

| Privacy issues | Consumer protection | |

|---|---|---|

| Soft Commitments | 33 | 33 |

| Intermediate Commitments | 34 | 10 |

| Hard Commitments | 22 | 0 |

| Total number of provisions | 44 | 43 |

a Privacy Issues

Fourty-four Latin American PTAs include provisions on privacy, usually under the concept of ‘data protection’. But the way this data is protected varies considerably, a truly mixed bag of binding provisions and non-binding provisions. The 2001 Canada–Costa Rica FTA was the first of these agreements dealing with privacy issues, in a non-binding declaration which is largely programmatic.Footnote 73 Later agreements include international cooperation activities to enhance the security of personal data, like sharing information and experiences on regulations, laws, and programmes on data privacy or data protection,Footnote 74 or on the overall domestic regime for the protection of personal information;Footnote 75 technical assistance in the form of exchange of information and experts or the establishment of joint programmes and projects;Footnote 76 maintaining a dialogueFootnote 77 or hold consultations on matters of data protection;Footnote 78 or in general other cooperation mechanisms to ensure the protection of personal data.Footnote 79

While some Latin American PTAs merely recognise the importance or the benefits of protecting personal information online,Footnote 80 in several treaties, parties specifically commit to adopting or maintaining legislation or regulations that protect personal data or the privacy of users of e-commerce,Footnote 81 in relation to the data’s processing and dissemination,Footnote 82 which may also include administrative measures.Footnote 83 Few agreements consider qualifications to this commitment, like the differences in existing systems for personal data protection,Footnote 84 or are explicit in highlighting the ‘best efforts’ nature of these commitments.Footnote 85

Certain treaties add that when developing online personal data protection standards, each party shall take into account international standardsFootnote 86 as well as criteria or guidelines of relevant international organisations or bodiesFootnote 87 – such as the APEC Privacy Framework and the OECD Recommendation of the Council concerning Guidelines governing the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Flows of Personal Data (2013).Footnote 88 Moreover, in a couple of treaties, the parties commit to publishing information on the protections (regarding personal data) it provides to users of e-commerce,Footnote 89 including how individuals can pursue remedies and how businesses can comply with any legal requirements.Footnote 90

Some agreements put a special emphasis on the transfer of personal data, encouraging the use of encryption or security mechanisms for users’ personal information, and their anonymisation, in cases where said data is provided to third parties, in accordance with the applicable legislation.Footnote 91 Furthermore, in a couple of agreements, parties commit to encouraging the development of mechanisms to promote compatibility between different regimes, recognising that they may take different legal approaches to protect personal information. These may include the recognition of regulatory outcomes, whether accorded autonomously, by mutual arrangement, or in broader international frameworks, and the exchange of information.Footnote 92 The USMCA explicitly recognises that the APEC Cross-Border Privacy Rules system is a valid mechanism to facilitate cross-border information transfers while protecting personal information.Footnote 93

But Latin American PTAs have also used more binding options to protect personal information online. A first option is to consider the protection of the privacy of individuals in relation to the processing and dissemination of personal data, as well as the confidentiality of individual records and accounts, as exception in specific chapters of the agreement, usually on telecommunications (to protect the privacy of non-public personal data of subscribers to public telecommunications services),Footnote 94 and financial services (adopting adequate safeguards for the protection of privacy and fundamental rights while permitting data transfer and processing).Footnote 95 Other agreements merely recognise principles for the collection, processing, and storage of personal data, without developing its content in detail.Footnote 96 The USMCA also acknowledges similar principles and the importance of ensuring compliance with measures to protect personal information and ensuring that any restrictions on cross-border flows of personal information are necessary and proportionate to the risks presented.Footnote 97

A second option focuses on the protection of personal data in specific sectors, like financial services. Some PTAs consider that where the financial information or financial data processing involves personal data, the treatment of such personal data shall be in accordance with the domestic law regulating the protection of such data.Footnote 98 A third option leaves the development of rules on data protection to a treaty body. For example, in the 2012 Colombia–EU–Peru FTA (which now includes Ecuador), the Trade Committee may establish a working group with the task of proposing guidelines and strategies enabling the signatory Andean Countries to become a safe harbour for the protection of personal data. To this end, the working group shall adopt a cooperation agenda that shall define priority aspects for accomplishing that purpose, especially regarding the respective homologation processes of data protection systems.Footnote 99 A fourth option allows countries to adopt ‘appropriate measures’ to ensure the protection of privacy while allowing the free movement of data. For that purpose a criterion of ‘equivalence’ is established, meaning that personal data may be exchanged only where the party that may receive it protects such data in at least an equivalent, similar, or adequate way to the one applicable to that particular case by the party that may supply them. To that end, the parties shall negotiate reciprocal, general, or specific agreements, or in a broader international framework, admitting private sector’s implementation of contracts or self-regulation. Up to now, this option has only been introduced in the 2017 Argentina–Chile FTA.Footnote 100

b Consumer Protection

Overall, forty-three Latin American PTAs include provisions on consumer protection or consumer ‘confidence’, explicitly applicable to e-commerce or digital trade, which are however largely non-binding. The 2001 Canada–Costa Rica FTA recognised that consumers who participate in electronic commerce should be afforded transparent and effective protection that is not less than the level of protection afforded in other forms of commerce.Footnote 101 Later agreements consider international cooperation on consumer protection, like sharing information and experiences on regulations, laws, and programmes,Footnote 102 on means for consumer redress,Footnote 103 or in confidence in e-commerce.Footnote 104 Other activities include the exchange of best practices, information or views on online protection,Footnote 105 or access to products and services offered online;Footnote 106 and maintaining dialogue/consultationsFootnote 107 about the protection in the ambit of electronic commerce,Footnote 108 or especially from fraudulent and misleading commercial practices in the cross-border context.Footnote 109

In the 2014 Pacific Alliance Additional Protocol, the parties agree to a number of additional commitments, including cooperation agreements for the cross-border protection of consumer rights; exchanging information about suppliers sanctioned for infringement of those rights; promote prevention measures and training initiatives on the protection of consumer rights in e-commerce and prevention measures; standardise the information that must be provided to consumers in this environment; and encourage e-commerce suppliers to comply with consumer protection regulations in the territory of the party in which the consumer is located.Footnote 110 Some Latin American PTAs also deal with consumer protection with reference to the adoption of domestic standards, but largely in a non-binding fashion, ‘recognising the importance’ of transparent and effective measures to protect consumers from fraudulent and deceptive commercial practices when they engage in e-commerce.Footnote 111 But in only a handful of agreements do the parties commit to adopting or maintaining consumer protection laws to prescribe these practices when they cause harm or potential harm to consumers.Footnote 112 Certain treaties also recognise the importance of cooperation between the respective national consumer protection agencies on activities related to cross-border electronic commerce,Footnote 113 or exchanging information and experiences in order to enhance consumer protection.Footnote 114 Few agreements consider that the parties may evaluate the use of alternative dispute resolution mechanisms,Footnote 115 or even online dispute settlement for the protection of consumer, if feasible.Footnote 116

But Latin American PTAs have also used more binding options to tackle consumer protection. Some establish a criterion of ‘equivalence’ that each party shall provide, where possible and in a manner considered appropriate, protection for consumers using e-commerce that is at least equivalent to that provided for consumers and other forms of commerce under their respective domestic laws, regulations, and policies.Footnote 117 Furthermore, the 2008 Australia–Chile FTA considers specific businesses obligations to protect consumers in e-commerce, including acting in accordance with fair business, advertising, and marketing practices, like providing accurate, clear, and easily accessible information about goods or services offered; avoiding ambiguity on intent to make a purchase; and provide easy-to-use, secure payment mechanisms and information on the level of security such mechanisms afford.Footnote 118

II Rules on Data

Several Latin American PTAs include general provisions on cross-border flow of data. These are found in both electronic commerce/digital trade chapters, as well as in dedicated chapters of sectors, where data flows play a central role, like telecommunications and financial services. Around half of all FTAs including data flow provisions have been concluded by Latin American countries (Table 13.5).

Table 13.5. Data flow provisions in Latin American PTAs

| Data flows | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General | Financial services | Telecommunications | Data localisation | |

| Soft Commitments | 6 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Intermediate Commitments | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hard Commitments | 8 | 33 | 31 | 8 |

| Total Number of Provisions | 18 | 33 | 32 | 9 |

Two types of data-related provisions are found on Latin American PTAs with e-commerce or digital trade chapters: (i) those referring to cross-border flow of data and (ii) those banning or limiting data localisation requirements, the former being more common, but with different levels of commitments across agreements.

1 Data Flows

There are basically two sets of provisions concerning data flows in Latin American PTAs: one binding, directly guaranteeing the free flow of data, the other non-binding, considering cross-border information flows as part of the cooperation activities between the parties. Few agreements consider some ‘intermediate’ type of clauses, including best endeavour provisions and commitments to future negotiations on data flows. PTAs concluded by Latin American countries are the largest group of trade agreements that include data flow provisions (thirty-nine agreements out of seventy-nine). Non-binding provisions on data flows appeared earlier. The first agreement having this type of provisions is the 2006 Taiwan–Nicaragua FTA, where as part of the cooperation activities, the parties affirmed the importance of working ‘to maintain cross-border flows of information as an essential element to promote a dynamic environment for electronic commerce’.Footnote 119 A similar wording is used in later agreements concluded by Peru, Mexico, Colombia, Costa Rica, and other Central American countries.Footnote 120 An intermediate type of provision is where the parties agree to consider commitments related to cross-border flow of information in future negotiations. This type of clause is found in the 2015 Pacific Alliance Additional ProtocolFootnote 121 and in the Modernisation of the Trade part of the EU–Mexico Global Agreement, currently under negotiation.Footnote 122 In the latter, the parties commit to ‘reassess’, within three years of the entry into force of the agreement, the need for inclusion of provisions on the free flow of data.

The first agreement having a binding provision on cross-border information flows is the 2014 Mexico–Panama FTA. According to this treaty, each party ‘shall allow its persons and the persons of the other Party to transmit electronic information, from and to its territory, when required by said person, in accordance with the applicable legislation on the protection of personal data and taking into consideration international practices’.Footnote 123 A much more detailed provision is found in the 2015 amended version of the PAAP,Footnote 124 which was then included in the 2016 TPP, and the TPP template has largely influenced subsequent agreements with data flow provisions.

After recognising that each party may have its own regulatory requirements concerning the transfer of information by electronic means, both the PAAP and the TPP stipulate that each party shall allow the cross-border transfer of information by electronic means, including personal information, when this activity is for the conduct of the business of a covered person. This shall not prevent a party from adopting or maintaining measures to achieve a legitimate public policy objective, provided that the measure is not applied in a manner which would constitute a means of arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination or a disguised restriction on trade; and does not impose restrictions on transfers of information greater than are required to achieve the objective. The same provision was kept in the 2018 CPTPP, signed after the withdrawal of the United States from the TPP and in DEPA.Footnote 125

After TPP, a similar hard rule on data flows has been incorporated into other trade agreements concluded by Chile, Argentina, Peru, Mexico, and Brazil, largely following the same wording.Footnote 126 In the 2017 Argentina–Chile FTA, there is a specific reference that the parties undertake to apply to the data received from the other party a level of protection that is at least similar to that applicable to the party from which the data originates, through mutual, general, or specific agreements.Footnote 127 In the USMCA, a footnote clarifies that a measure restricting data flows is not considered to achieve a legitimate public policy objective, if ‘it accords different treatment of data transfers solely on the basis that they are cross-border in a manner that modifies the conditions of competition to the detriment of the service suppliers of the other Party’.Footnote 128

2 Data Localisation

In recent years, some preferential trade agreements have also started to include provisions on data localisation, either banning or limiting such requirements. An important difference with data flow provisions analysed in the previous section is that the large majority of data localisation provisions are of a binding nature. Again, PTAs concluded by Latin American countries are the largest group of trade agreements that include data flow provisions (nine agreements out of seventeen). The 2015 amended version of the Pacific Alliance Protocol includes a provision on the use and location of computer facilities, stipulating that no party may require a covered person to use or locate computer facilities in the territory of that party as a condition for the exercise of its business activity. An exception in this regard considers that nothing shall prevent a party from adopting or maintaining measures to achieve a legitimate public policy objective, provided that such measures are not applied in a manner that constitutes a means of arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination, or a disguised restriction to trade.Footnote 129

In 2016, the TPP considered largely the same provision on location of computing facilities, requiring in addition that such measures shall not impose restrictions on the use or location of computing facilities greater than are required to achieve the objective. The same provision was kept in the 2018 CPTPP.Footnote 130 A similar hard rule on data localisation largely following the same wording was included in the 2016 Chile–Uruguay FTA and in DEPA.Footnote 131 The 2018 Brazil–Chile FTA has a minor deviation from the TPP drafting, as it does not require that data localisation provisions are the least restrictive measure to achieve the public policy objectives. In this regard, its wording is closer to the PAAP.Footnote 132

A more succinct version of this type of provision is found in the USMCA, which stipulates that no party shall require a covered person to use or locate computing facilities in that party’s territory as a condition for conducting business in that territory, without considering any further exception.Footnote 133 One of the few provisions on data localisation that are not directly binding is found in the 2017 Argentina–Chile FTA. Under this treaty, the parties merely ‘recognise the importance’ of not requiring a person of the other party to use or locate the computer facilities in the territory of that party, as a condition for conducting business in that territory. To this end, the parties undertake to exchange good practices, experiences, and current regulatory frameworks regarding the location of servers.Footnote 134

D Legal Framework of E-Commerce and Personal Data Protection in Latin American Countries

As mentioned, a group of five Latin American countries, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Panama, and Peru, have concluded an important number of trade agreements with clauses or chapters on e-commerce and data flows, representing around half of all the PTAs that include these provisions. In this section we examine whether the domestic legal framework of these countries corresponds to their international commitments, taking as a case study the regulation of data protection.

Most Latin American countries, sharing the tradition of European continental civil law, have recognised the right to the protection of personal data and the right to privacy as separate legal notions. Several Constitutions of the region recognise explicitly the right to privacy, but those of Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, Peru, and Venezuela also include the ‘habeas data’, or the right to the protection of personal data. But even in countries where this mechanism is not expressly contained in the Constitution, the relevant courts have recognised the ‘right to control’ personal information.Footnote 135

Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Panama, and Peru have also domestic regulations on the processing of personal data in both the public and private sectors. Chile was the first to introduce such framework in 1999, followed by Colombia in 2008.Footnote 136 However, in most of these countries there are concerns on the proactive application of data protection laws and regulations by their respective Data Protection Authority (DPA) – and in some cases such authority does not exist. Other challenges commonly mentioned are the harmonisation of cross-border cooperation for the protection of privacy with other DPAs and police and judicial authorities; the promotion of privacy management programmes including obligations to respond, inform, and compensate data owners in case of violation of security that affects personal information; and the enhancement of interoperability with other regional and national privacy and data protection frameworks.Footnote 137

I Chile

The regulation of electronic commerce in Chile is largely contained in the general domestic legislation (e.g. Code of Commerce, Civil Code). Only in some cases, special norms have been created to respond to the challenges posed by new technologies. In 2002, Chile adopted a law on electronic documents and electronic signature (Law 19,799) which explicitly recognises the legal principles of freedom to provide services, free competition, technological neutrality, international compatibility, and equivalence of electronic support to paper support, meaning that everything contained in electronic format has the same validity as a paper document.Footnote 138 However, self-regulation of e-commerce as a complement of legal norms is still very relevant.Footnote 139

Although rules on the protection of consumer rights were established back in 1997 (Law 19,496), these norms did not refer to e-commerce until 2004, when amendments introduced by the Law 19,955 included explicit provisions to deal with the challenges posed by digital commerce.Footnote 140 In 1999, Chile enacted the oldest personal data protection regulation in the region, the Law 19,628 ‘On the protection of private life’, which include provisions on the treatment of personal information in public and private databases. The law has been amended a couple of times: firstly, forbidding credit risk predictions or assessments that are not based on objective data like late payments of natural or legal persons (Law 20,521 of 2011); and secondly, establishing the principle of finality in the treatment of personal data of economic, banking, financial, or commercial nature (Law 20,575). Some other sectoral laws deal with data protection, like the regulation prohibiting the inclusion of sensitive personal data in ‘active transparency’ public websites (Law 20,285 of 2008); or the law making all information regarding healthcare procedures and treatments sensitive data (Law 20,584 of 2015).Footnote 141

This regulation has been criticised for its lack of enforcement, being outdated and insufficient for the expectations of both private sectors and regulators,Footnote 142 and lacking a specific and independent institution that serves to effectively protect the rights associated with data processing.Footnote 143 In response to those criticisms in June 2018, a Constitutional amendmentFootnote 144 recognised the ‘right to personal data protection’, complementing the protection already granted to private life, as well as the honour of the person and their family.Footnote 145 A bill of law to implement this right that would introduce a data protection system similar to the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the creation of a DPA is still under discussion at the Chilean Congress.Footnote 146

None of the existing domestic rules mentioned earlier contain any restrictions on international transfer of data, but the bill of law currently discussed at the Congress includes certain restrictions derived from the express recognition of principles, such as consent, finality (in general terms, not only for the specific sectors mentioned earlier), proportionality, quality, security, liability, and legality of data processing.Footnote 147

II Peru

Peru largely relies on general civil law to address electronic commerce issues, although it has included special provisions on e-commerce in consumer protection laws,Footnote 148 like the ‘Law on Digital Signatures and Certificates’ (Law 27,269 of 2000) which regulates electronic signatures and gives them the same validity and legal effect as handwritten signatures; and the ‘Anti-spam Law’ (Law 28,493 of 2005), which governs the use of non-solicited advertisement e-mailing.Footnote 149

Under the 1993 Peruvian Constitution, everyone has the right that information services, computerised or not, public or private, do not provide information that affects personal and family privacy. Furthermore, the Constitution limits the right to request and receive information from any public entity, in cases where the information affects personal privacy, or those that expressly are excluded by law or for reasons of national security. The Constitution also protects bank secrecy and tax reservation, which can only be lifted at the request of the judge, the National Prosecutor, or a congressional investigative commission in accordance with the law.Footnote 150 The Peruvian Constitution establishes the guarantee of ‘habeas data’ (which proceeds against the acts or omissions, by any authority, official or person that violates or threatens to violate the aforementioned rights).Footnote 151 The proceedings of the habeas data were initially detailed in a separate law (Law 26,301 of 1994), but are now included in the Constitutional Procedural Code (Law 28,237).Footnote 152

Based on the Constitutional provisions referred to earlier, the Personal Data Protection Law (PDLP – Law 29,733 of 2011) specifically protects the use of personal data of any natural person and applies to both private and state entities. In March 2013, the PDLP was complemented by a Regulation (Supreme Decree 003-2013-JUS) that develops, clarifies, and expands its requirements and set forth specific rules, terms, and provisions regarding data protection. Another statute (Law 27,489 of 2001) regulates activities related to risk centres and companies that handle sensitive personal data and information posing higher risks to individuals (like that related to financial, commercial, tax, employment or insurance obligations or background of a natural or legal person that allows evaluating its economic solvency).Footnote 153

Peruvian PDLP was criticised for the lack of a DPA, which was finally created by Legislative Decree 1,357 of 2017. Today, the Directorate for the Protection of Personal Data is the primary agency in charge of enforcing data protection matters, which is part of the General Directorate of Transparency, Access to Public Information and Protection of Personal Data (NDPA). Yet, the fact that the DPA is not autonomous and is under the authority of the Ministry of Justice has been criticised by sectors of the civil society.Footnote 154

The 2017 reform also strengthened the regime for the protection of personal data and the regulation of interest management. According to Article 15 of the Law 29,733 transfers of personal data beyond Peruvian territory require consent from data subjects, and they can only be transferred to jurisdictions with ‘adequate’ levels of data protection,Footnote 155 or to jurisdictions with lower levels, subject to a privacy guarantee from the data controller. However, some transfers of personal data are generally allowed, like those that take place as part of an international treaty on cross-border flow of personal data in which Peru is a party (which would include the PTAs mentioned in the first part of this chapter); international judicial cooperation or among intelligence agencies; those needed to execute a contractual relationship, medical treatment or a scientific or professional relation involving the owner of the personal data subject; and those conducted for bank or stock transfers trading. Notification to the DPA is required for international transfers.Footnote 156

III Panama

Electronic commerce in Panama is governed by the Law 51 of 2008 (amended by Law 82 of 2012), and a couple of Executive Decrees (No. 40 of 2009 and No. 684 of 2013), which regulate the creation, use, and storage of electronic documents and signatures, using a registration process, as well as the supervision of providers of data storage services.Footnote 157 The regulation was based on the 1996 UNCITRAL Model Law on electronic commerce and provides for enforcement through the General Directorate of Electronic Commerce (DGCE).Footnote 158

Until 2018, Panama did not have a law dedicated to the protection of personal data. A bill regulating this issue was introduced in the Congress in August 2018 and approved in October the same year. The Law of Protection of Personal Data (Law 81 of 2019) was promulgated only on 31 March 2019. The new law establishes that the processing of personal data may only be carried out when there is consent of the owner or when the law permits it.Footnote 159 The legislation is applicable to all databasesFootnote 160 containing personal information, whether of nationals or foreigners, who are within the territory of the Republic of Panama or whose data controller is domiciled in the country. The cross-border treatment of personal data originated or stored in Panama that is confidential, sensitive, or restricted is permitted provided that the data controller and the country of destination of the data comply with protection standards that are equal or superior to those indicated in Law 81. However, the same regulation considers several exceptions to this rule – for example, when owners of the data have given their consent for the transfer and cross-border treatment; when the transfer is necessary for the execution, present or future, of a contract in the interest of the owner; when it is related to bank transfers, money, and stock market securities; when it is information required by law under international agreements or treaties signed by Panama.Footnote 161 Law 81 also establishes that those responsible or custodians of a database that transfer personal data to third parties must keep a record of them, which must be available to the newly created National Authority of Transparency and Access to Information (ANTAI), but only in case that such authority would require it. The same law also creates a Council for the Protection of Personal Data, which makes recommendations of public policies and evaluates cases entailing the protection of personal data, and also provides advice to ANTAI.Footnote 162 The actual implementation of this new law is a matter that cannot be ascertained at the moment of this writing.

IV Colombia

The regulation of e-commerce in Colombia is found mainly in Law 527 of 1997 or ‘Electronic Commerce Law’, which establishes the ‘principle of functional equivalence’, between electronic signature and autograph signatures, data messages and written documents, and sets up rules for the certification of digital signatures and for the creation of certification entities. Several additional laws complement this framework on consumer protection, like the Law 1,480 of 2011, which establishes special obligations for suppliers of goods and services that are offered using electronic means like special information duties (identification of provider, characteristics of the goods, means of payment available, contract text, etc.), duties to conserve information, and procedures of filing petitions, complaints, and claims.Footnote 163

The Colombian Constitution recognises two fundamental personal data rights: the right to privacy and the right to data rectification.Footnote 164 Personal data processing is further regulated by two statutory laws and several decrees that set out data protection obligations. The first one, the ‘Habeas Data Law’ (Law 1,266) was enacted in 2008, after intense discussions, and regulates the handling of information contained in some personal databases,Footnote 165 especially of financial, credit, commercial, services data collected in Colombia or abroad.

In 2012, a statutory law for the protection of personal data was enacted (Law 1,581). This statute regulates personal data processing, as well as databases including special rules for sensitive data and data collected from minors. The law further regulates data processing authorisation and procedures, and creates the National Register of Data Bases (NRDB) administered by the Superintendence of Industry and Commerce (SIC, the Colombian DPA). Law 1,581 is applicable to all data collection and processing in Colombia.Footnote 166 Under Article 26 of Law 1,581 of 2012, transfers of private or semi-private personal data must be authorised by data subjects and are not allowed to jurisdictions that the SIC regards as not providing ‘adequate’ levels of management of personal data. It is understood that a country offers an adequate level of data protection when it complies with the standards set by the SIC on the subject, which in no case may be less than those required by the Law 1,581. Exceptionally, beyond those cases, international transfers are allowed for exchange of financial information for transfers and banking operations; for medical, health, and public hygiene reasons; pursuant to international treaties joined by Colombia; for contracts involving the data subject and a counterpart; and when required by public interest.Footnote 167

Despite the existing regulation, it has been criticized that Colombia still does not have successful initiatives that seek to adapt the personal data protection regime to the era of big data and the digital economy. Some scholars find fault with the fact that this law focuses on the protection of commercial and financial data and leaves normative gaps preventing the complete protection of personal data in Colombia.Footnote 168 Others have pointed out that the law is not applicable to those responsible or in charge of data processing that do not reside or are not domiciled in Colombia, even though they perform operations on personal data of persons who reside, are domiciled or located in Colombia.Footnote 169

V Costa Rica

Currently in Costa Rica there is no electronic commerce law or framework that regulates all the essential aspects of online commerce. In 2013, a bill on services for the information society (or ‘Electronic Commerce Law’) was presented to the Legislative Assembly but has not been approved yet.Footnote 170 However, some related laws have already been enacted, such as the Law 8,454 of 2005, of certificates, digital signatures, and electronic documents.Footnote 171 Additionally, in 2017, a reform of the Regulation to the Law of Promotion of Competition and Effective Defence of the Consumer, introduced a new chapter on Consumer Protection in the Context of Electronic Commerce.Footnote 172

Data privacy regulation in Costa Rica is contained in two laws – the Law 7,975 of 2000, ‘Undisclosed Information Law’, which makes it a crime to disclose confidential and/or personal information without authorisation, and the Law 8,968 of 2011 on Protection in the Handling of the Personal Data of Individuals (amended in 2016), which together with its by-laws, regulates the activities of companies that administer databases containing personal information, and recognises the ‘Right to Self-Determination of Information’, which includes access, rectification, cancellation, and opposition to the processing of personal data. The same law created the Agency for the Protection of Data of Inhabitants (PRODHAB), as the DPA and regulatory body of databases and requires the mandatory paid registration of all databases, public or private, for distribution, dissemination or commercialisation purposes.Footnote 173

Concerning transfers of data, Law 8,968 stipulates that controllers of public or private databases can transfer personal data only if the data subject has provided express and valid consent. However, the law is not clear whether this provision relates to transfers within Costa Rica or transfers to a third country.Footnote 174 As a consequence of such unclear regulation, the transfers of personal information from a database to a service supplier, technological intermediary, or entities in the same ‘economic interest group’ are not considered as transfers of personal information and therefore do not need authorisation from the data subject.Footnote 175

The local press has reported that the main weakness in the protection of information is the lack of care for the users when disclosing personal data, without reviewing the conditions of use. Additionally, the lack of registration of private-led databases (despite the fact that is a mandatory procedure) and the lack of adequate human and financial resources of PRODHAB have been criticised.Footnote 176

E Conclusion

As we have seen throughout this chapter, a group of Latin American countries have pioneered the inclusion of e-commerce and data flow provisions in preferential trade agreements. These countries have done so, in a largely consistent way, with an important level of regulatory convergence on certain objectives and principles (like facilitate and promote e-commerce, avoid unnecessary barriers, and address the needs of SMEs), as well as on specific commitments, such as moratorium on custom duties, electronic authentication, source code, consumer protection, personal data, data flows and data localisation, yet, with different levels of legalisation. These principles and commitments were largely developed in the conclusion of PTAs with developed countries.

But Latin American countries have also advanced new principles on e-commerce and data flows in the conclusion of trade agreements. Around half of all PTAs including data flow provisions on telecommunications or financial services have been concluded by Latin American countries, and the 2014 Mexico–Panama FTA was the first PTA with general binding provision on cross-border information flows. Latin American PTAs are the largest group of treaties that include provisions either banning or limiting requirements of data localisation. Additionally, the largest number of agreements including provisions on stakeholder’s participation or the principle of ‘technological neutrality’ has also been concluded by Latin American countries. Only three PTAs explicitly recognise the principle of ‘net neutrality’Footnote 177 and all have been concluded between Latin American countries.Footnote 178

A further testimony to the creative role of Latin American countries on these topics is the announcement made on 18 May 2019 on the side lines of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) meeting of Ministers Responsible for Trade in Viña del Mar, Chile, of the start of the negotiations of a Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DEPA) between Chile, Singapore, and New Zealand.Footnote 179 The agreement was finally concluded on 21 January 2020 covering all aspects of the digital economy to support trade in the digital era, and also going beyond existing commitments, looking at a range of emerging issues, like cross-border data flows, digital identities, artificial intelligence, electronic invoicing, and open government data.

However, the five examined Latin American countries have not all had the same consistency at domestic level, with national regulations on certain topics addressed in PTAs that lag behind what has been committed to in those agreements, particularly on the issue of data protection. The Organization of American States (OAS) has reported that a consistent and coherent regional approach to the protection of personal data has not yet emerged in Latin America. In 2015, the Inter-American Juridical Committee adopted a ‘Proposal for the Declaration of Principles of Privacy and Protection of Personal Data in the Americas’ with the purpose of urging the OAS member states to adopt measures to respect privacy, reputation, and dignity of people in the Americas.Footnote 180 At the same time, a group of five countries of the region that are considered to have a moderate (Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Peru) or limited (Panama) data protectionFootnote 181 are leading the conclusion of PTAs including digital trade and data flow provisions. While these provisions are not all binding, general provisions on data flows, as well as on specific sectors (financial services and telecommunications), have become commonplace in recent years. In contrast, data protection provisions in these PTAs are largely non-binding or their scope of application is left to domestic regulations.

The different levels of commitment and approaches on these issues found in these five countries between the international and domestic regulation, as well as their implementation (or lack thereof), potentially create the possibility of future conflicts, if some of these countries intend to change the domestic regime for data protection. If both regimes are not well-coordinated, Latin American countries could be limited in their policy space to enact rules that contradict international commitments. For example, from the group of countries mentioned earlier, only Colombia, Panama, and Peru have established a criterion of equivalence for the international transfer of personal data, meaning that those countries agree that personal data may be exchanged only where the party which may receive them undertakes to protect such data in at least an ‘adequate’ way to the one applicable to the party from where that data originates. In all the PTAs examined in this chapter, we find such a rule only in the 2017 Argentina–Chile FTA.

In several of these countries discussions are taking place to reform data protection laws to a model that is closer to the EU’s GDPR. Up to now, the only Latin American countries the EU has determined as having and adequate levels of data protection under the GDPR are Argentina and Uruguay.Footnote 182 What would happen if other countries of the region made a policy change to be GDPR adequate and implement their own adequacy policies? Could that be a violation of PTA commitments to allow the cross-border transfer of information by electronic means that do not include such exception?Footnote 183 Is this a problem waiting to happen?

A matter for further research is to determine why these Latin American countries have pioneered the development and diffusion of electronic commerce and data flow provisions in PTAs. Is this a sort of path dependency or the influence of third countries, a reaction to particular economic interests, or rather the will to be in a position of rule-makers and not rule-takers?Footnote 184 The answers to these questions could help to shed a light on the development of new rules for digital trade.