It is a central irony in the war on terrorist finance that it has proved counterproductive in the context of Somalia. A key assumption in counterterrorism policy is that weak and collapsed states serve as a breeding ground for terrorist recruitment and a refuge for global terrorist cells. Yet the regulatory constraints imposed on informal financial transfers have had the unintended consequence of potentially undermining state-building efforts in the very region of the world which is in most need of building and strengthening formal institutions. Somalia represents an important example in this regard. The hawwalat system continues to represent the most important conduit of capital accumulation. Moreover, in addition to ensuring the survival of millions of Somalis, the hawwalat have the potential to play an important role in ongoing state-building and consolidation efforts. A key determinant of state formation is the ability to both encourage and tax private economic activity in order to consolidate political control and expand the infrastructural reach and power of the state. The case of northern Somalia has clearly illustrated that achieving success in this sphere both reduces clan-based conflicts and stems the tide of extremism and terrorism.

In the more stable regions of Somalia (i.e., northwest and northeast) where I conducted my field research, political leaders have managed to gain the trust and cooperation of the Somali businessmen operating the hawwalat companies, who have earned windfalls from the lucrative trade in remittances and foreign currency. As a result, state builders, most notably in Somaliland (i.e.,northwest Somalia), have established a high level of peace and stability and revived governance institutions.1 In November 2017, Somaliland witnessed an unprecedented fourth round of democratic elections with no violent incidence of extremism reported in any parts of the territory.2 With the financial assistance of the Dahabshil3 hawwalat and the cooperation of the business community, in northern Somalia, government employees collect revenue; salaried and uniformed police keep law and order; courts administer justice; and ministers dispense public services. In this respect, criminalizing major parts of the informal sector threatens the fragile peace and state building that has been achieved in some parts of Somalia.4

The Origins and Legacy of State Collapse

To understand Somalia’s contemporary economic and political dynamics, it is important to examine the underlying reasons for the collapse of the state. As Jamil Mubarak has keenly observed, “most of the resilient features of the post-state-collapse economy, which are attributed to the informal sector, emerged in response to the policies of the [Siad Barre] government.”5 Indeed, in Somalia while the boom in labor remittances in the 1970s and 1980s signaled a resurgent private sector the bulk of the country’s labor force was “accommodated mostly as apprentices or family aides in a vast network of shops and workshops” – the informal sector, as distinct from the parallel sector from which the former received its money.6 Moreover, when the recession period set in, it led to a great deal of unemployment. In fact, as early as 1978, a survey of the urban labor force demonstrated that officially registered wage earners numbered only 90,282 persons out of an estimated labor force of 300–360 thousand.7

By the mid-1980s the drop-in oil prices and the consequent slump in the Gulf countries increased unemployment (reaching as high as one-third) and remittances drastically declined. For a society that had for over a decade relied on its livelihood to be financed by remittances from family members outside Somalia the effect was devastating. Moreover, while many relied on supplementary income derived from informal, small-scale businesses financed by remittances, or some support from relatives who were farmers or pastoralists, the 1980s would signal increasing economic competition, pauperization, and social discontent. Moreover, the livestock trade which had always been transacted on the free market and whose profits accrued to private traders operating along fragmented markets that helped to both create and expand the parallel sector also declined drastically in 1983. In that year, Saudi Arabia imposed a ban on cattle imports from all African countries after the discovery of rinderpest. Livestock export earnings plummeted from $106 million in 1982 to $32 million two years later.8

This played a large role in Somalia’s crisis. By the late 1980s, the overall economic picture for Somalia was grim: manufacturing output, always small, had declined by 5 percent between 1980 and 1987, and exports had decreased by 16.3 percent from 1979 to 1986. According to the World Bank, throughout the 1980s real GNP per person declined by 1.7 percent per year.9 What was at stake in political terms was control of the exchange rate and hence the parallel market which constituted the financial underpinning of the clientelist system underpinning Barre’s dictatorial rule. Eventually, mounting debt forced President Siad Barre to implement economic austerity measures, including currency devaluations, as a way to channel foreign exchange into the central banking system. However, this belated attempt at economic reform, and particularly financial liberalization, failed because Barre could no longer compete with the remittance dealers. The hawwalat continued to offer better rates and safer delivery than the state’s extremely weak and corrupt-ridden regulatory and financial institutions could provide. Barre resorted to increasingly predatory and violent behavior, particularly as opposition, organized around clan families, grew. He singled out the Isaaq clan, the main beneficiaries of the remittance boom, for retribution. In Mogadishu and other southern towns, the government attempted to destroy the financial patrons of the Isaaq-led Somali National Movement (SNM) by arresting hundreds of Isaaq merchants and professionals. Generally, Barre’s policies against the Isaaq aimed to marginalize them both politically and economically. For example, because the Isaaq enjoyed a monopoly over the livestock trade – a monopoly made possible by their control over the northwestern port of Berbera – Barre placed tariffs on livestock exports from the northern ports. He also outlawed the sale of the mild narcotic qat, a profitable source of revenue for the clan. This policy of economic repression, coupled with Barre’s arming of non-Isaaq militias to fight and displace the Isaaq from their lands, further consolidated Isaaq clan identity and solidarity against both the state and neighboring clans, such as the Darod-Ogadenis.10

The ensuing civil war naturally exacted a debilitating cost on the economy. A rising import bill (petrol prices rose by 30 percent in 1988 alone) resulted in acute shortages of basic consumer goods and led to hoarding and the circulation of fraudulent checks as a popular form of payment. Barre’s lifting of all remaining import restrictions in an effort to stimulate imports had no effect since most of the population were by this time outside government control either because of active opposition or because they were engaged in informal activity. Even Barre’s attempts to keep his military alliance intact by raising its pay 50 percent and doubling military rations did not forestall opposition within the ranks as at first the Ogadenis and then other clans went into opposition.11

Barre’s policies also meant that remittances from the Isaaq diaspora came to play an increasingly key role in financing both clan members’ economic livelihoods and the SNM’s insurgency against the regime. Prior to the outbreak of civil war in 1990, members of the Isaaq represented more than 50 percent of all Somali migrant workers, partly as a result of their historically close ties to the Gulf and their knowledge of Arabic. A large proportion of their remittances went to supply arms to the rural guerillas. In 1990 delegates of the SNM received USD 14–52 million; and the total remittances transferred to northern Somalia were in the range of USD 200–250 million.12 The SNM provided crucial financial and logistical support to the Hawiye and other rebel clans, and guerilla warfare spread quickly to the central and southern parts of the country. In January 1991, the Hawiye-based United Somali Congress (USC), led by Gen. Muhammad Farah ‘Aidid and backed by the SNM, ousted Barre from Mogadishu.

By the time Barre’s regime fell, the Somali state ceased to exist as reinforced clan identities were asserted in the struggle over territory and increasingly scarce resources. In the North the Somali National Movement dominated. The Somali Salvation Democratic Front (SSDF), consisting mainly of the Majeerteen, a subclan of Barre’s own Darod clan, became active once again in the northeast and central regions. Formed as early as 1978, this was the oldest opposition force, but it had little success due to the absence of an autonomous financial base. In the south the Somali Patriotic Movement (SPM) was made up of the Ogadeni, another subclan of the Darod. Between the Juba and Shebelle rivers in the southwest the Rahenwein were represented by the Somali Democratic Movement (SDM) whose weak social position reflects their agro-pastoral base. Possessing the most fertile region in the country, the Rahanwein became the main victims of the war-induced famine and violence as powerful neighboring warlords sought to displace them. Also caught in the fighting in what became known as the “triangle of death” were other riverine populations, namely the Bantus who as descendants of slaves retained an inferior social status. In the center, around the capital of Mogadishu, the epicenter of conflict, was the Hawiye-based United Somali Congress (USC). The USC, founded only one year prior to Barre’s ouster, was a relative newcomer to the conflict, but came to occupy a prominent position in 1990 mainly because of its hold over the capital. When the USC broke up the following year into the Hawiye subclans of the Haber Gidir led by Ali Mahdi and the Abgal led by Mohamed Farah Aideed, internecine violence increased dramatically.13 The fateful decision of southerner Ali Mahdi to declare himself president in a hastily convened 1991 “reconciliation” conference in Djibouti within days after Aideed’s forces had driven Barre into exile in Kenya caused an escalation of the violence in Mogadishu. Aideed refused to recognize Mahdi’s appointment and attacked his forces in the capital, while years of northern resentment came to the fore resulting in the Isaaq’s unilateral declaration of an independent Republic of Somaliland in May 1991.

In ensuing years clan militias emerged to fill the vacuum of the collapsed state. Across the early 1990s, all of Somalia, but particularly the southern and central regions, witnessed a pattern of increasingly violent interclan and intra-subclan fighting. These conflicts broke out largely because of competition over economic resources as well as violent struggles over political authority. Most notably, the USC was divided into two Hawiye sub-subclans: the Hawiye/Habr-Gedir/Abgal clan of ‘Ali Mahdi and the Hawiye/Habr-Gedir/Sa‘ad clan of Gen. ‘Aidid.14 Tension between the two factions arose when in the wake of Barre’s ouster, the Abgal faction unilaterally formed an interim government and appointed Mahdi as president.15 The two opposing movements claimed sovereignty over Mogadishu and utilized their subclan networks and militias to regulate entrance and exit from these areas by demanding payment and protection fees.16 Initially, this was represented by the division of the city between the north and south, which were controlled by ‘Ali Mahdi and Gen. ‘Aidid respectively.17 Eventually, the conflict led to the disintegration of the USC – a harbinger of the heightened level of violence that has plagued southern and central Somalia to the present day.18

As newly organized subclan networks rapidly proliferated in a society absent institutions of law and order, the business of protection within Somalia’s unregulated economy quickly came to dominate large swaths of southern and central Somalia. The new subclan networks that coalesced over different territories used coercion and violence to extract taxes from village harvests and commercial establishments. They also took hostages for ransom. Indeed, the “economy of war” in Somalia took several forms. Youth gangs began to engage in activities such as robbery and looting as a means to generate income. More profitable, however, were illicit informal economic activities, including the embezzlement of foreign-aid funds; the printing and circulation of counterfeit money; the smuggling and exportation of charcoal, qat, copper, and machinery; and, more recently, piracy.19 Piracy, in particular, became a sophisticated economic activity primarily because it is facilitated by a very profitable alliance between some members of the business community and clan militias.20 Writing poignantly in the wake of state collapse, Somali scholar Abdi Samatar noted that the “opportunistic methods with which groups and individuals marshaled support to gain and retain access to public resources finally destroyed the very institution that laid the golden egg.”21

Variations in State Building

One of the main legacies of the collapse of the Somalia state was the strong emergence of clan-centered forms of social organization throughout the country. In the wake of the disintegration of the formal institutions of the state, clan solidarity emerged as the primary basis of political, social, and economic organization. However, while interclan and subclan conflict continues to plague much of Somalia, in the northwest state builders have successfully established a relatively stable and democratic state resulting from a highly complex process of negotiation and reconciliation between clans. This included the demobilization of armed militias and the restoration of law and order.22 Remarkably, since it broke away from the rest of Somalia in 1991, Somaliland has managed to build internal stability without the benefit of international recognition or significant foreign development assistance. Indeed, few international organizations participated in ending internal conflicts or substantially invested in establishing security through disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration or to promote democratization.

Somaliland’s remarkable success in transitioning from a clan-based system of governance to multiparty elections was a result of a contentious and often violent process that included the use of traditional mechanisms of conflict resolution. In a constitutional referendum held on May 31, 2001, the vast majority of eligible voters in Somaliland approved a new democratic, multiparty system, thereby eliminating the institutionalization of clan leadership that had existed under the previous system of governance.23 In 2010 and again in 2017, Somaliland further consolidated its nascent democracy by holding successive rounds of presidential elections, which brought a new political party to power in its capital of Hargeisa. Although Somaliland is now widely recognized as a legitimate state among its population, it has not been granted formal recognition by the international community. Nevertheless, Somaliland has consolidated its state building efforts. Ken Menkhaus, a foremost expert of the politics of the region, has noted that Somaliland has made a relatively successful transition from a clan-based polity to a multiparty democracy by holding local, presidential, and legislative elections and even overseeing a peaceful constitutional transfer of power following the death of the influential president Muhammad Ibrahim Egal in 2002.24

In contrast to Somaliland, the semi-autonomous northeastern region of Puntland, once touted as a success of the grassroots approach to reestablishing national stability and widely viewed as one of the most prosperous parts of Somalia, continues to experience high levels of insecurity and political tension. At its root are poor governance, corruption, and a collapse of the intraclan cohesion and pan-Darod solidarity that led to its creation in 1998.25 In contrast to Somaliland’s leaders, none of the four presidents “did what was needed.”26 They did not embark on institution building, establish a proper development and regulatory framework, or build legitimate and efficient security arrangements. Nor has the leadership played a positive role in national reconciliation. In contrast to Somaliland’s political elite, they have not managed to forge peace among different clans and subclans within Puntland or with their neighbors. “It was,” in the words of one Somalia scholar from the region, “a lost opportunity since civil society was overwhelmingly supportive of the idea of an autonomous Puntland.”27 Indeed, when I returned to conduct further research in 2010 the state of security of the region was profoundly precarious. Residents routinely complained that salaries were not paid on time for public officials; police officers were forced to work on a volunteer basis; and competition over resources, including land, fuel, and fishing rights, led to intermittent conflict between nomads, agro-pastoralists, and fishermen. As one resident of Eyl, in the Nugal province of Puntland, put it: “[W]e have no police force to enforce the law; elders continue to try to intervene to settle disputes since there is an absence of a strong administration and no security. Only mobs and thugs prosper in a community without order.”28

Standing in starker contrast to both Somaliland and Puntland, Somalia – that is, the southern and central regions of the Republic of Somalia that remain, at least, nominally, a part of that state – has failed to build durable state institutions. It remains beset by continued clan conflict, Islamist extremism, and displacement. Unlike Somaliland, which has benefited from a more united and cohesive clan structure organized under the Isaaq clan family, Somalia is home to a far more diverse and less unified constellation of different clans and subclans. In recent years, the rapid rise of militant Islamist activism has influenced state building efforts in variable ways. In April 2006, the Somali capital city of Mogadishu came under the control of the Union of Islamic Courts (UIC), a cross-clan organization comprising Somalia’s Islamist organizations. The UIC seized power from the then increasingly weak clan-based Transitional Federal Government (TFG) in an attempt to establish a system of governance based on shari‘a instead of clan loyalty.29 After sixteen years of intraclan fighting and conflict, the UIC implemented a particularly austere and militant version of shari‘a (including huduud punishments) to institute law and order. As a consequence, the Islamic courts achieved a short-lived measure of stability in the city before the UIC was ousted in 2007 by an alliance of Ethiopian and US military forces.

Developments in Somaliland, Puntland, and the Republic of Somalia represent alternative approaches to state building that transcend conventional understandings of the role of ethnic and Islamic networks in state formation. Examining these contrasting political trajectories helps illuminate how the transnational character of Somalia’s civil war was not only an obstacle to peace building but also, in the case of Somaliland, an opportunity for state formation in the context of an increasingly internationalized economy. Examining the state building projects in Somaliland and Puntland alongside the emergence of Islamist militancy in Somalia also reveals how war, state making, and clan and Islamist networks are related in variable ways.

State Building in Weak States

Considering the civil conflict underpinning the disintegration of the state in Somalia, a closer analysis of the balance between civil conflict, protection, extraction, and state making is required in order to understand the trajectory of state-building efforts in contemporary Somalia. As scholars of state formation have long observed, historically state building has been ancillary to war making.30 To support and finance their wars, rulers developed centralized control over private armies, developed institutions to settle disputes, and established rules and courts to control the behavior of the people within their boundaries. Most important, war makers strive to develop fiscal and extractive capacities since success in war depends on the state’s ability not only to tax its subjects, but also to generate revenue from domestic and transnational financial sources.31

In the case of Somalia, this framework usefully highlights the interaction between war making, state making, and capital accumulation (i.e., extraction). Moreover, this model has important implications for our comparative analysis of state building efforts in Somaliland, Puntland, and Somalia. This is because all the regions have experienced intermittent interclan strife while simultaneously embarking on efforts at state building and state consolidation. Consequently, variations in the way the actors have attempted to collect taxes, make war, and eliminate their local rivals are important and highly unpredictable. Throughout Somalia, the business of “protection” – “the racket” in which a local strong man forces merchants to pay tribute through threats of violence – has indeed determined political developments and the social organization of collective action in various parts of the country. The emergence of regionally based political organizations and initial attempts to establish local currencies, and institute law and order though military and ideological means, are very illustrative here.

Nevertheless, this understanding of the state building process in post-conflict settings falls short in two important ways. The first problem is that this framework’s focus on interstate war as the mechanism underpinning state formation obscures the fact that this type of war is a rare occurrence in the developing world and in Africa in particular.32 Indeed, as a number of scholars have documented, since 1945, intrastate wars have dominated armed conflict.33 This empirical reality associated with the frequency of intrastate wars has led students of state building to refute the applicability of Tilly’s model, asserting that in the absence of an external threat and the presence of an internal one, the state can no longer penetrate society to extract resources.34

What has not been sufficiently analyzed, however, is this influential model’s eurocentrism. According to Charles Tilly, the history of state formation reveals that “states built upon religious organizations were significantly weaker than secular states, as the latter were less fragmented and, therefore, more capable of accumulating capital and means of coercion.”35 But this line of reasoning assumes a priori that a state based on Islamic institutions, or for that matter clan networks, cannot survive in the modern state system. Contrary to this conventional understanding of state formation, state building experiments in Somalia, though based on clan identity and invented tradition, may, depending on the interplay between formal political authorities and identity-based trust networks, represent legitimate alternatives to secular institutions. The fact that Islamist experiments such as the Union of Islamic Courts in central Somalia have failed is due to a combination of external and internal dynamics. This is clearly in evidence when we compare the variations of state building across this Muslim country.

Equally important in the case of Somalia is the fact that developing states are far more vulnerable to regional and international interventions than European states were at the time of their formation. They are also crucially affected by shifts in the global economy. However, what still needs to be explained is the precise manner in which international economic imperatives are interacting with local economic and cultural variations in ways that are decisively shaping political developments in the northwest and northeast. For example, why are clan-based cleavages enjoying greater political salience and popular legitimacy in Somaliland, while Islamist identification is making more inroads in the more homogenous northeast (Puntland)?36 Indeed, without understanding the impediments as well as opportunities posed by international economic linkages in state-building efforts, any understanding of these developments in Somalia can only be partial. In particular, given the fact that remittance inflows represent the largest source of foreign exchange and are relied upon as a major source of income by 46 percent and 38 percent of all urban households in Somaliland and Puntland, respectively, it is also important to address the latter’s complex role in contemporary political developments.

Clan Networks and State Disintegration

As Charles Tilly famously observed, over most of history, no regime has been able to survive without drawing on resources and the support held by trust networks such as religious or kinship groups. “Rulers’ application of various combinations among coercion, capital and commitment in the course of bargaining with subordinate populations produces a variety of regimes.”37 Tilly focused on the threat that contemporary democracies may face if major segments of the population withdraw their trust networks from public politics, but this development has far more profound consequences for weak states like Somalia where it can jeopardize the very foundation of state institutions leading to the collapse of central political authority. In order to properly examine Somalia’s civil unrest and its implications for state building we must first turn to precolonial traditions that once regulated the country’s social, political, and economic order. In doing so, a clear distinction can be drawn between traditional social organizations and the divisive politicization of clanship that occurred during and after the colonial period.

The nature of precolonial Somali society depended largely on communal interdependence rather than rigid hierarchal authority.38 Patrilineal kinship ties are derived from one of six clan families – Dir, Isaaq, Hawiye, Darod, Digil, and Rahanwein. Somaliland consists mainly of the Isaaq, Dir, and Darod clans, while southern Somalia is comprised of the Hawiye, Digil, and Rahanwein clans.39 Subclans known as diya-paying groups (blood compensation groups) were derived from these larger clan families and served to unify kinsmen within a mediating structure. More specifically, kinsmen under these groups are bound by a contractual alliance based on collective payment for wrongs committed by any group member. In effect, this alliance serves as a political as well as a legal entity.40

However, beyond patrilineal genealogy and blood ties, cross-clan cooperation was manifested in both the tenets of Islam and customary law or Xeer. According to I. M. Lewis, Islam is “one of the mainsprings of Somali culture,” and historically, Somalia’s religious leaders have positioned themselves outside of the conflict between clans.41 Similarly, Xeer served as a unifying structure, which was “socially constructed to safeguard security and social justice within and among Somali communities.”42 This structure, utilized in the ongoing processes of state building in Somalia, thus served as a Somali-wide social contract in that it governed and regulated economic relations as well as social life. In a society that lacked an overarching state structure, where the household was the basic economic unit, and where the means of daily survival were widely distributed, the Xeer prevented the exploitation of one’s labor or livestock.43 Moreover, within precolonial Somalia there did not exist individuals or groups who could monopolize coercive power or economic resources. Clan elders were restricted from exercising such control beyond their households, and their status as political leaders was limited to their role as mediators within and among their clans.44 In effect, Somali society was regulated by traditional principles of interaction based on clanship, Islam, and Xeer.45 The Somali scholar Ahmed Yusuf Farah explained the complex interaction of these three aspects of Somali communal life in eloquent terms:

The sub-clan affiliation is an important one because it represents the most important social group in judicial terms. Known as the Diya paying group, it is at this level of the sub-clan where elders appoint representatives to pay and receive blood compensation as, for example, if someone kills another. It is this group which is charged with negotiating the terms of material value. This is what is known as Xeer: that is, the customary code of conduct which regulates relations between and among groups. It defines the sharing of resources like water, land and blood compensation. [Moreover], in areas where Islamic tradition violates the Xeer the elders just ignore them … for them [elders of the subclans] material and class interests and competition override religious strictures.46

The introduction of the colonial order, beginning in the early nineteenth century, drastically transformed these traditional networks of the precolonial period. The direct effects of this transformation disrupted the equilibrium of clans and the management and distribution of resources.47 Although northern and southern Somalis were exposed to different colonial strategies, both regions experienced a high level of intrusion into their social and political systems. Both British and Italian administrative apparatuses politicized the leadership of clan elders. This created a system of chieftainship whereby the role of the clan elder was transformed from regulating clan relations and resources to regulating access to state benefits.48 In Somaliland, for example, clan chiefs were paid a stipend to enforce diya-paying, thus justifying the British colonial strategy of collective punishment.49 This practice of chieftainship throughout Somalia undermined the legitimacy of clan elders and their traditional authority by violating the very traditional social structures that had once mitigated against hierarchical authority.

Importantly, however, the colonial experiences of northern and southern Somalia varied in certain respects in ways that illuminate the context of present variations in the success of peace and state building in the different regions of the country. Specifically, the Italian colonialists adopted a method of direct rule, economic intervention, and commercialization of the pastoral economy in southern Somalia. In contrast, British Somaliland was left economically “undisturbed and governed by indirect rule.”50 The economic effects sustained in southern Somalia undermined the traditional system of “communitarian pastoralism” by producing and distributing agricultural goods according to political motivations rather than household or communal necessity.51 The commercialization of the economy and direct taxation of livestock produced a nascent class system that privileged merchants and political elite while exploiting the agricultural producers – a process that was previously prevented by the institution of the Xeer.

It is this class system that set the stage for the transformation of clan networks into a hardened clannism under the authoritarian rule of President Siad Barre whereby certain clans enjoyed the political and economic largesse of the state. Upon taking over the presidency in 1969 Siad Barre began an aggressive campaign to eradicate clan loyalties in favor of an irredentist Pan-Somali identity and he went so far as to outlaw any acknowledgment (public or private) of the existence of clans.52 Contrary to this policy of nationalism, however, Barre engaged heavily in the instrumentalization of clan politics. In order to strengthen his power, he adopted “a divide and rule through blood ties” strategy that pitted one clan or subclan against the other.53 Through such a policy, he was able to elevate his clan and that of his family members to a level of prominent political and social status. I. M. Lewis has argued that it was the Darod subclans of Barre – the Marehan, Ogaden, and Dulbahante – that dominated representation in parliament.54 Aside from its supremacy over the political arena, by the 1970s this new political elite controlled most of Somalia’s businesses particularly when Barre took over the formal financial sector.55

By 1977, Barre had extended his irredentist campaign beyond the territorial boundaries of Somalia, supporting ethnic Somali movements in Kenya, French Somaliland, and Ethiopia. The most significant demonstration of this support was extended to militants from his mother’s clan, the Ogadeen in Ethiopia of both the Somalia Abo Liberation Front (SALF) and the Western Somalia Liberation Front (WSLF).56 This prompted a forceful retaliation by the Ethiopian government, Somalia’s long-time rival, thus commencing the Somali-Ethiopia war. Though the war initially engendered national solidarity, Barre’s regime came under heavy scrutiny as a result of the influx of hundreds of thousands of Oromo and Ogadeen refugees and Somalia’s defeat in 1978.57 Such scrutiny resulted in an attempted coup by military officers and political opponents of the Darod/Majeerteen clan in 1978. Upon the failure of the coup, many of the perpetrators fled to Ethiopia and, by 1981, had organized under the movement the Somali Salvation Democratic Front (SSDF). Though it was comprised of Darod, Hawiye, and Isaaq clan members, by 1992 it was apparent that the SSDF was a Majeerteen militia.58 Abdullahi Yusif, the first president of Puntland following the collapse of the state, was among the leading cadres of SSDF throughout the 1980s. Less than thirty years after attempting to overthrow the Barre regime through a clan-based militia and building strong ties with rival Ethiopia, Yusif was made president of Somalia’s internationally supported Transitional Federal Government.59

Importantly, while Barre’s polices institutionalized political preference along the lines of those clans and subclans that were closest to his own, they repressed other clan groups. The Isaaq, in particular, Somaliland’s majority clan, were politically and economically marginalized under Barre’s predatory regime.60 The Isaaq were often subject to violent interclan violence instigated by the regime directly or by proxy-militias. Barre’s tactic was to “militarize the clans be creating militias, giving them weapons, and then implicating them in the repression against a targeted clan segment” in order to fragment potential opposition to his regime.61 In the early 1980s, for example, Barre resurrected Darod/Ogadeeni-Isaaq clan disputes over access to grazing water in the northern pasturelands. By extending his patronage to Ogadeeni fighters through arms supply, Barre encouraged them to fight the Isaaq and any disloyal Darod subclans.62 By 1988, Barre’s army had destroyed much of Somaliland’s two major cities: Hargeisa and Burao. In response to the increasing strength of the Ogadeen and the alienation of the Isaaq clan under Barre’s regime, it was at this historical juncture that the Somali National Movement (SNM) was created in 1981 and based in Ethiopia until 1988. Importantly, its origins lay in the strength of the Isaaq diaspora in the Gulf, whose remittances contributed significantly to Somaliland’s economy. The creation of the SNM provoked hostile retaliation and further alienation from Barre’s regime, which in turn strengthened the legitimacy, popularity, and internal cohesion of the various Isaaq subclans.

The Isaaq SNM movement was a clear example of both the utilization of clan networks for political interests and the increasing need for Somalis to seek political and economic refuge in clan identity from a repressive authoritarian regime. However, it would not have succeeded in producing a coherent and united opposition to Barre if the movement did not benefit from their engagement in informal economic activities in general and labor remittances in particular. Due to the economic alienation and state repression of Somaliland under the Barre regime, northern businessmen sought protection within clan-based credit systems, or abbans to manage their business networks and organize informal remittances from overseas.63 The abbans connected local businessmen to the hawwalat, which utilized subclan norms of reciprocity to facilitate the trade.64 This allowed northern businessmen to finance the armed struggle through remittances and informal networks during the Barre regime.

In addition to the Isaaq-led SNM, a large number of clan-based militant groups emerged in the late 1980s that played a key role in Barre’s ouster. The Hawiye clan movement – the United Somali Congress (USC) – was based mostly in central and southern Somalia and formed its own militia in 1989. Indeed, by 1991 the tendency was for “every major Somali clan to form its own militia movement.”65 However, in a development that would be a key factor in future state-building projects in the country, aside from the Isaaq in later years, the general tendency was that most clan-based movements were plagued by intraclan rivalry among subclans in the post-collapse era. To be sure, interclan as well as intraclan feuds had certainly existed in precolonial Somalia, but the violence under Barre and in the civil war period was a drastic deviation from the traditional relations governing clan interaction.66

The legacy of the Barre regime was thus one of political, economic as well as societal destruction facilitated through the manipulation of clan networks in an attempt to strengthen his supporters and his increasingly personalized form of authoritarian rule. The result was the emergence of centrifugal movements centered on clan and subclan networks. From within this environment emerged insurgent militias who employed the sentiment of clan in order to rally allegiance, legitimate their authority, and extract resources – a far cry from the role of “traditional” clan elders. But just as these movements such as the SNM, SSDF, and UCM, based on clan networks, challenged and eventually overturned centralized coercive power and extractive capabilities (i.e., the Barre nation state), in the aftermath of the collapse of the state they also embarked on building new state institutions, albeit with varying degrees of success.

Clan Networks and State Building in Somaliland

Paradoxically, Somaliland, which was devastated by two waves of violent power struggles involving intraclan warfare (in 1992–1993 and 1994–1996), and which has a more heterogeneous population, has achieved better results than Puntland in reviving the basic institutions of governance. The Republic of Somaliland was established in 1991 as a result of the Grand Conference of the Northern Peoples of Burao, where the Somali National Movement joined with clan elders from the various subclans to establish an interim government. The government was given a two-year mandate with the tasks of accommodating non-Isaaq clans into the state structure, drafting a constitution, and preparing the population for presidential elections.67 Due to its weak revenue base and inability to mediate among intraclan rivals, rather than subverting traditional authority, the government assiduously turned to clan elders to manage local security and reconciliation.

Somaliland’s relatively cohesive and united clans, forged in the long and violent struggle against Siad Barre’s regime, is certainly one of the root causes of its stability. Nevertheless, it is important to point out that the Isaaq-dominant region was not immune from internal divisions following its unilateral declaration of independence. Fighting erupted in Somaliland among intraclan rivals immediately following the creation of the SNM-led government headed by ‘Abd al-Rahman ‘Ali Tur. As in southern and central Somalia during the same period, subclan competition over power and resources fragmented former SNM militia leaders along five major Isaaq subclans. This was followed by fierce violence in March 1992 when the government attempted to gain control over Berbera port and its very lucrative revenue. Indirect taxation at the port at this juncture would have provided crucial resources for state building efforts. Not surprisingly, the other subclans, not wishing to cede their local revenue to the state, rejected the move.68 Although a peace conference in 1993 reestablished some security, by 1994 intraclan conflicts were resurrected over the issue of resource extraction. Until that time, the airport in the capital of Hargeisa had been controlled by the Idagele subclan of the Isaaq, which enforced its monopoly over air taxes and landing fees. This conflict was sparked when the state, headed by Abdulrahman Ali Tur, tried to take control of the Hargeisa airport away from the Idagele subclan. The conflict led to over a year of violence in Somaliland and the displacement of hundreds of thousands of civilians.69

In the wake of intraclan conflicts in 1991 and 1992, Somaliland’s elders convened two conferences in Sheikh and Borama. These conferences, referred to by their Somali name shir beeleed, made use of the traditional role of clan elders as community mediators, signaling a return to the Xeer system.70 The 1993 Borama conference was overseen by a guurti, or national council of clan elders, and produced both a peace charter and a transnational charter. The former reinstated Somalia’s precolonial traditional social order by establishing a Xeer in accordance with the tenets of Islam as a mechanism through which to govern both inter- and intra-clan relations.

The transnational charter established an innovative bicameral legislature, oversaw the transfer of power from interim president ‘Abd al-Rahman ‘Ali Tur to the democratically elected President Muhammad Ibrahim Egal, and called for a formal constitutional referendum under Egal’s new government.71 As such, it struck a balance between traditional Somalian and Western state forms: local clan elders were encouraged to utilize their traditional roles as a way to eradicate interclan enmities while also participating in a temporary power-sharing coalition until a constitutional draft could be agreed upon by the elders of all the clans in Somaliland. Though the shir beeleed established the parameters for peace, intraclan violence in Somaliland persisted under the Egal administration. Once again, clan elders convened to mediate among the communities under a second national reconciliation conference held across 1996 and 1997. This pivotal conference successfully ended the war and adopted an interim constitution that called for presidential elections and the establishment of a representative multiparty system of governance.72 By 1999, a draft constitution was prepared, and on May 31, 2001, it was accepted by 97.9 percent of the population.73

But how precisely did the new constitution transcend the clannism forged in the colonial period and that had been so devastating to the country throughout the last decades? First, accredited political parties were obliged to draw at least 20 percent of electoral support from four of Somaliland’s six regions, thereby ensuring that no party ran solely on a clan-based platform.74 Second, to demonstrate the Guurti’s adherence to the precolonial era’s non-hierarchical clan tradition, the constitution replaced the nonelected council of clan elders with directly elected district councils. Moreover, under the Egal administration, the new government of Somaliland forged mutually beneficial clientelist ties with clan elders. In particular, the Hargeisa government allowed elders of the most prominent clans significant control over a large proportion of the influx of remittances and sufficient autonomy to invest these capital inflows in livestock markets and other sectors of the local economy without imposing heavy taxes. These ties of cooperation have allowed the government to have a degree of social control over clan elders. Moreover, by ensuring that remittance inflows remain unregulated by any formal bureaucratic authorities, officials in Hargeisa have kept them from falling prey to political entrepreneurs. In light of the government’s isolation from the global financial system, these connections have been vital for the survival and growth of Somaliland.

The state building model adopted by the government and clan elders of Somaliland represents a viable alternative to a system of top-down patrimonial politics that allows for a certain degree of clan loyalties at the grassroots without imposing a repressive political order from above. In this instance, political order for a society in crisis is rooted in local politics built on clan networks rather than built by the heavy hand of the state. Somaliland serves as an example of how informal social networks and traditional authority can be utilized in the service of peace rather than war. Indeed, the relative success of Somaliland’s approach to state building and democratization was crucially underpinned by a lengthy, self-financed, and locally driven interclan reconciliation process through the 1990s, leading to a power-sharing form of government, providing an important base for Somaliland’s enduring political stability and for the reconstruction and development in the region. One female community leader from Hargeisa eloquently captured the remarkable, conciliatory, and nonpunitive elements, underpinning the indigenous conflict resolution method that played a crucial role in rebuilding trust between previously warring clans and subclans:

In our tradition when people convene for peace making and peace is accepted in the process of arbitration, whether it is between clans, two people, or two groups, both sides gain some things. Our justice is not about what side is wrong or what side is right; rather it is a win-win situation of mutual benefits for both sides … In the case that one side feels like it is the loser and other side believes it is a winner, it would be hard to implement the [peace] agreement unless you had a strong government.75

Importantly, a key element in the success of the resolution of clan conflict in Somaliland had to do with settling marital disputes as an important way of addressing the larger, and often violent, conflicts between kinship groups. I personally participated in a high number of deliberative meetings designed to restore marital relations, which I quickly came to understand as a pivotal aspect of the peace-building process. This is because since the clans were intermarried prior to the conflict, deliberations over marital issues were not only common; they were rightly perceived by clan elders and the general community as central to resolving a wide range of social as well as economic disputes between clans and subclans.

Going It Alone: Building a State in the Absence of International Recognition

Nevertheless, the lack of international recognition has been a mixed blessing for Somaliland. On the one hand, Somaliland has managed to avoid the legacy of aid dependence that bedeviled the postcolonial state under the Barre regime. Indeed, the Republic of Somaliland’s existence is in direct violation of UN Resolution 1514 (1960), which forbids any act of self-determination outside the context of former colonial boundaries. Since the African Union upholds the official UN position, it too denies recognition to Somaliland, a neglect that seems to have had positive results for the state.76

On the other hand, the lack of international recognition has had grave consequences for the development and strengthening of formal institutions. International commercial law denies certification to Somaliland on the grounds that it would infringe upon the preexisting certification of Somalia, thereby nullifying all contracts made under this certification.77 Because formal participation in the global economy is impossible, transnational norms and institutions that regulate foreign and trade agreements cannot be enforced in the country. Thus, while Somaliland has succeeded in entering the global economic order through informal financial networks, it remains largely isolated from foreign aid and technical assistance. Somaliland’s groundbreaking peace conferences of 1992, 1993, and 1997 were entirely self-financed.78 While for some scholars this has meant that Somaliland operates in the “shadows” of the global economy, empirically this claim does not hold for two very important reasons. First, this characterization of a Somaliland operating under the radar of the global economy underestimates the importance of remittance inflows. Second, it obscures the importance of the role of locally generated taxes (i.e., direct taxes) in building the kind of state that has proved more stable than its counterparts in Puntland and Somalia.

How, in the face of this neglect and economic exclusion, has the Somaliland state been able to maintain control over its territory and achieve a relatively peaceful state of affairs? Part of the answer lies in the careful crafting of a power-sharing system undergirded by newly revitalized clan networks and traditional authority. As Mark Bradbury, Adan Yusuf Abokor, and Haroon Ahmed Yusuf have asserted, this power-sharing system has proven critical to the process of reconciliation and recovery in Somaliland, succeeding where numerous efforts in Somalia have failed.79 In addition, the leadership and policies of the late president Muhammad Ibrahim Egal played an important role in laying the groundwork for durable state institutions. Thirdly, the Somaliland state has established a working relationship with hawwalat owners and other members of the business community, which allowed the state to strike a delicate balance, crucial to state formation, of encouraging unregulated remittances flows while taxing other forms of private economic activity. By winning the trust and cooperation of the hawwalat owners, the state managed to establish a system for taxing the largest source of revenue generation and also to encourage private enterprise. Somaliland leaders have done this by substantial structural changes since the early 1990s. Rather than regulating the remittance economy, authorities have dissolved monopolies, done away with rigid economic controls, and pursued a deregulated free market economy that has enlisted the trust and cooperation on the part of the business community.80 It is in this way that Somaliland authorities have achieved remarkable gains in establishing a delicate balance between taxing and encouraging private economic activity.

Under President Ibrahim Egal’s tenure in particular, Somaliland’s leaders also managed to reduce clan-based conflicts, most of which were sparked when faction leaders tried to extract revenue from different ports in order to gain political control. The success of both Egal and his successor Dahir Riyale Kahin in these efforts resulted both in a substantial peace and an impressive stability as state builders sought to revive basic institutions of governance.

Labor Remittances and State Building: Resource Curse or Social Safety Net?

Somaliland’s success in state building is even more remarkable given its heavy reliance on remittances in the context of relatively weak formal institutions. Indeed, while work on the political impact of remittances remains sparse, recent scholarship has generally argued that remittances maybe a “resource curse” akin to natural resource rents and foreign financial assistance. This is because, as one important study noted, “they are revenue sources that can be substituted for taxes and serve as a buffer between government performance and citizens.”81 In other words, the informal (or parallel) channels through which remittances are transferred often insulate recipients from local conditions and reduce incentives to participate in politics. However, given the sheer volume of remittance inflows, in the case of Somaliland, remittances have played a very important, albeit indirect, role in generating effective government performance. A closer examination of the popular resistance on the part of hawala bankers to several attempts at regulation, and the response of Somaliland’s leaders to this resistance, demonstrates that a bargain was eventually struck between nascent state builders and the most powerful agents of revenue generation in the territory.

In Somalia remittance inflows have the potential to obstruct state building in two key ways: they are difficult to tax by central authorities, and their mode of operation privileges clan networks rather than cross clan or Islamic cleavages. State builders thus face a strong challenge in generating revenue needed for governance and encouraging cross-clan cooperation, which is crucial for peacemaking, national reconciliation, and legitimating political authority. Indeed, we cannot fully understand the path that development has taken in northern Somalia without appreciating how international economic linkages – in the form of remittance inflows – pose impediments as well as opportunities to state building. Labor remittances represent the largest source of foreign exchange, and the majority of urban households in both Somaliland and Puntland rely upon them as a major source of income. Because the average Somali household is composed of eight members whose daily income together totals less than 39 cents, transfers from family members living abroad are crucial for securing a livelihood. Indeed, as much as 40 percent of Somali urban households rely on such funds. Moreover, the benefits of remittance flows are felt across the spectrum of Somali subclans, albeit in unequal terms. For example, only one of the four subclans of the Isaaq, which has historically supplied the majority of migrant workers, revealed 8 percent of its households receiving remittances from abroad, whereas approximately 31 percent of the Habr-Awal subclan’s families count on informal transfers (Figure 6.1).

Figure 6.1 Remittance recipients by Isaaq subclans in Somalia.

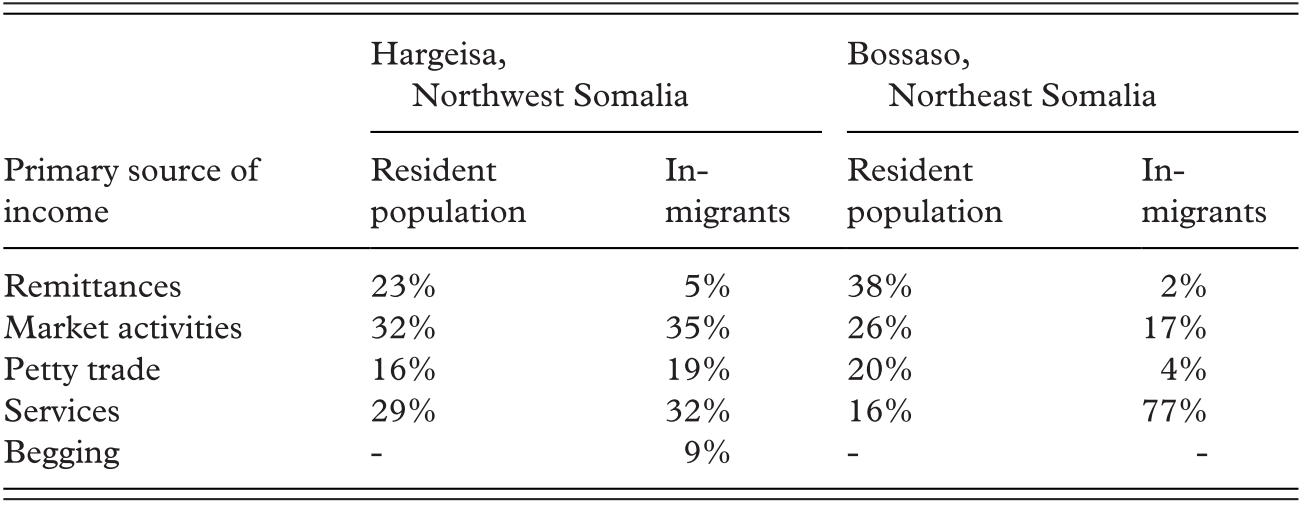

Remittances are usually a supplementary source of income; in addition to receiving assistance from relatives, a Somali family typically has more than one member involved in informal economic activities. Nevertheless, it is important to highlight that Somalis in both Somaliland and Puntland rely heavily on money from overseas relatives sent through the hawala agencies. This is clearly evident when one considers the proportion of remittances vis-à-vis other sources of income in both the northwest and northeast (Table 6.1).

Table 6.1 Main sources of income by percentage of households in Somalia

| Primary source of income | Hargeisa, Northwest Somalia | Bossaso, Northeast Somalia | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resident population | In-migrants | Resident population | In-migrants | |

| Remittances | 23% | 5% | 38% | 2% |

| Market activities | 32% | 35% | 26% | 17% |

| Petty trade | 16% | 19% | 20% | 4% |

| Services | 29% | 32% | 16% | 77% |

| Begging | - | 9% | - | - |

Market activities include currency exchangers, market stalls, tea stalls, qat sellers, charcoal and water delivery, and meat sellers. Service jobs include masons, porters, civil servants, waiters, drivers, and unskilled laborers. Trade activities include livestock brokers (dilaal), shops/restaurants, import/export traders, and cloth retailers.

Following the collapse of the Somali state, the family unit has come to encompass three or more interdependent households. In addition to assisting poorer urban relatives, a large proportion of urban households support rural kin on a regular basis. While only 2 to 5 percent of rural Somalis receive remittances directly from overseas, Somali’s nomadic population still depends on these capital inflows. In northern Somalia, for example, 46 percent of the sampled urban households support relations in pastoralist areas with monthly contributions in the range of USD 10–100 a month; of these 46 percent, as many as 40 percent are households that depend on remittances from relatives living abroad. Consequently, the link between labor migration, urban households, and the larger rural population is a crucial and distinctive element in Somalia’s economy.

As the most important source of foreign exchange and a key source of daily income in both Somaliland and Puntland, remittances thus play a pivotal role in the contemporary state-making enterprise. Indeed, state building in Somaliland has been largely successful because the Isaaq-backed leadership has also been able to encourage remittance transfer and gain the cooperation of the wealthy “remittance barons” with whom they share a kin relation. Consequently, in Somaliland, the Isaaq largely control revenues accruing from remittances, organized by the private hawala agencies, as well as taxes from the port of Berbera. The Somaliland government, particularly under Egal’s tenure, thus was able to partially finance governmental institutions, including an effective police force, throughout its territory.

Once Somaliland’s leaders realized the important role remittances play as a social safety net for the local population, they negotiated a delicate, albeit often contested and conflictual, bargain. This bargain consisted of government authorities ensuring that hawalas remain unregulated by state authorities while the former pursued a more transparent and less-repressive taxation policy.82 Importantly, the fact that remittances insulated the majority of the population from economic and social deprivation of the kind that would lead to protest and civil conflict greatly facilitated the eventual reduction of taxation in Somaliland thereby bolstering the political legitimacy of the new state among its citizens. In other words, in the case of Somaliland, while remittances remain untaxed by government officials this does not suggest that this engenders a weak link between state institutions and remittance recipients. Indeed, rather than demobilize citizens, the fact that remittances increase incomes dramatically and provide a social safety net for government officials pursuing economic policies means that they have increased civic engagement in ways that not only can be discerned from several protests against government policies deemed unjust or illegitimate, but also in participation in local and presidential elections thereby helping to consolidate democracy.83

Somaliland’s much touted ability to generate locally generated revenue to finance the building of state institutions absent foreign assistance is greatly facilitated by the fact that remittances support the type of welfare services that often reduce the burden on government finances. Over time, this has made it possible for the government to collect taxes and license fees from business and real-estate owners and impose duties on the trade in qat as well as imports and exports through the port of Berbera with a decreasing level of opposition in civil society. Most of these businesses and real-estate properties have been financed, at least in part, by remittances from Somalis living abroad. Remittances also provide the much-needed hard currency that has led to the expansion of the important livestock trade and even allowed Hargeisa to reduce taxes and fees as, for example, in the elimination of fees for primary and secondary schooling. The success of these policies is related to the important role remittances continue to play in supporting general household expenditures.84 A rare study on this subject put it succinctly:

The financial and social contributions and material support of the Somaliland diaspora and their high level of engagement in Somaliland is stimulating the ongoing development in the country and is crucial for sustaining peace. Their engagement comes in the forms of monetary and social remittances, tourism, and economic and social investments. Remittances provide the much-needed hard currency for trade, support the livelihood of many households, allow some households to establish small businesses, and finance the ongoing construction boom in the country. These business investments in trade, telecommunications, luxury hotels, and light industries do lead to modest job creation and attract a host of other infrastructures. As for social investments, numerous members of the diaspora are either setting up or are actively engaged in local NGOs, medical and educational facilities, and political parties that are positively contributing to the social and political development of the country.85

Moreover, while the role of traditional clan elders (Guurti) was indeed a critical institution in terms of the success of the series of meetings that focused on putting a stop to hostilities (Xabad joogi) and promote reconciliation (Dibu-heshiisiin) between the hitherto waring subclans of the Isaaq and non-Isaaq clans, these meetings shared three important characteristics: they were funded largely by Somaliland communities themselves, including those in the diaspora; they involved the voluntary participation of the key figures from each of the clans affected; and decisions were taken by broad consensus among delegates.86 As I observed by participating in several mediation efforts led by traditional community leaders in both Hargeisa and Bossaso, the process is not only a lengthy one; it is also costly in that it requires the dispatching of carefully selected leaders, deemed legitimate by the local communities, to conflict areas. Since formal law enforcement institutions and local authorities were ill-equipped to provide adequate sources, it was often left to regional and local authorities to solicit funds for these peace-building missions from the community, particularly from notable remittance brokers, livestock traders, and prominent Somalis living abroad. This was especially important, in the rural parts of Somaliland such as Boroma, Burao, and Yirowe where formal authorities lacked adequate financial resources for even basic operational and logistical needs.

If remittances have served as a social safety net enabling the peaceful pursuit of taxation policy, the role of the diaspora has often played an even more direct role in facilitating the success of the state-building enterprise over time. Given that Somaliland has not generally benefited from international recognition or significant foreign development assistance, remittances from the diaspora have played a key role in the state-building enterprise. Indeed, as one Somalilander who was intimately involved in a series of conflict resolution negotiations stressed, “peace building in Somaliland would not have succeeded were it not for the help, resources, and contributions of our diaspora.”87 To be sure the diaspora has not always played a positive role in Somaliland’s rebuilding process. During the civil conflicts of 1992 and 1994–1996, they provided funds and other support for their clan militias. Nevertheless, by the late 1990s, remittances sent by members of the Somali diaspora were invested in businesses, and they helped to reestablish basic services that, in serving as a safety valve for Somalilanders, sustained the peace-building and state-making processes. Importantly, and in the context of the absence of international engagement and the relative weakness of its state institutions, Somaliland serves as an important case study in that it shows the importance of international remittances and diasporic communities in the process of rebuilding states in the aftermath of severe civil conflict.

However, this negotiated bargain in pursuit of state building was not achieved without wrenching political conflict. In the early 1990s, as intra-Isaaq clan enmities and divisions between former SMN leaders led to successive rounds of civil conflict, non-Isaaq clans intervened to make peace in the important conference held in Sheikh town. It was at this conference that the most important source of revenue for the state, the port at Hargeisa, reverted to Abdulrahman Tur (the first president of Somaliland). It was also at this conference that the council of elders (Guurti), which became the cornerstone of the hybrid political system bringing together clan networks and the modern institutions of the Somaliland state, was established as a key informal social institution in the state-building project.88

Nevertheless, for all of its rightly touted political success, Somaliland remains constrained by limited avenues to generate resources and revenue for the central state. This is because the majority of Somalilanders are nomadic and engaged in the livestock trade which is difficult to tax. Tax revenues are predominately generated from international trade acquired from the port at Berbera. Consequently, throughout the 1990s the nascent state not only expended a large portion of its budget to build a military and police force, under Egal’s presidency, patronage politics reemerged that threatened to undermine state-building efforts. Prior to changes in policy, the Somaliland administration faced severe opposition after it imposed financial controls and restrictions, which greatly alienated the private sector including the Hawala bankers and the large livestock traders.

The narrow resource base and weak extractive capacity of the new state compelled the government in Hargeisa to resort to printing money thereby creating inflation.89 The introduction of new currency by Hargeisa in the mid-1990s also had grave political as well as economic consequences; it was one of the main reasons for the reemergence of conflict between the Isaaq subclans in the mid-1990s. One former SNM member in Burao, in the region of Toghdeer, explained succinctly how and why this policy exacerbated intraclan conflict at the time:

The main reason for the conflict [1994–1996] was Egal’s introduction of the Somaliland shilling. He did this to support his own Haber Awal subclan as a form of patronage. This caused inflationary pressures and to this day most traders here in Burao work with the Somalia shilling although they accept the Somaliland shilling. This is for two reasons: This first is political. Egal’s government has yet to be deemed legitimate and so residents here in Buroa and in Yirowe will not legitimate his currency. Economically, since the livestock market is mostly linked to central and eastern Somalia–the Somalia shilling is the real base of the local economy. The purchasing power of the Somalia shilling is stronger. The Somalia shilling is three times less expensive. We can eat and purchase commodities much cheaper in Burao than in Hargeisa.90

Importantly, and despite strong resistance against any form of government intervention on the part of many traders I interviewed, the livestock trade, the cornerstone of the domestic economy, was gravely and adversely affected by the unregulated environment in the aftermath of the collapse of the state. This naturally led to mistrust among clans throughout the country. In Somaliland, the livestock trade operates on the basis of a hierarchical structure consisting of a network of brokers who collect livestock from several markets throughout Somalia on behalf of seven or eight large traders. An important source of recurring conflict is that it is difficult to get the traders to cooperate in an unregulated and highly competitive environment. During my time in several livestock market hubs in Somaliland, I observed that the large livestock traders were from the Haber Jalo and Haber Awal Isaaq subclans. The Haber Younis often complained that the Haber Awal not only dominated the trade, but with the assumption to power of Egal at the time they were viewed as dominating the government as well. Livestock brokers routinely cited evidence that since the Haber Awal dominate Berbera and the outlying region where the port is located, they have long dominated the livestock trade.91 Ultimately, however, the Egal administration was able to provide services and build an association of livestock traders which, over time, introduced a distinct corporate culture to the livestock trade. The result was that the trade recovered and in so doing helped to create more generalizable trust across the clan divide and in the Hargeisa administration itself. Thus, another important reason for Somaliland’s success is that governmental authorities in Hargeisa were able not only to cooperate with the hawala brokers soliciting loans and contributions from them; they were also able to negotiate an acceptable and legitimate level of regulation of the all-important livestock trade. Consequently, in this way they were able to built trust among the most important actors in the local economy.

Puntland and the Struggle to Build a Viable State

In contrast to Somaliland, state building in Puntland has stagnated after making significant inroads in the 1990s. So far, popularly legitimate formal structures of modern governance have played a negligible role in the affairs in northeast Somalia. Ultimately, the relative failure of state building in Puntland has been the result of the ambivalent vision of “statehood” that underpinned the foundation of the state, the predatory behavior of successful leaders, and the failure to pursue economic policies in ways that would generate trust and legitimacy among the different subclans of the Darod, the dominant clan family in the region.

Puntland initially followed a similar pattern of state building to neighboring Somaliland. In May 1998 it was established as a result of the intervention of clan elders of the Darod-Harti subclan in the city of Garowe. The Isimada, or clan elders, of the Harti instituted a regional administration that encompassed northeast Somalia, including Sool and Sanag which continue to generate serious tensions between Puntland and Somaliland. Headed by Abdullahi Yusif, the leaders of the Somali Salvation Democratic Front (SSDF) at the time enlisted the cooperation of clan elders in order to establish an autonomous state. Importantly, however, the primary motivation was political survival rather than independence. The Majeerteen, Warsengeli, and Dhulbahante subclans of the Darod in particular felt strongly that they needed to unite in order to avoid emerging as losers in the nation-wide clan struggle for power and territory. In addition, they felt that territorial control would serve as a powerful bargaining chip in their attempts to recreate a central national territory.92

Initially, Puntland managed to form a functioning regional state. Clan elders elected Abdullahi Yusif as president, a charter was adopted following a long consultation process among the different subclans of the Darod, and a regional parliament chosen by the clans was established. Yusif also managed to dampen intraclan hostilities by including non-Majeerteen Harti clans in the Garowe Conference that formally established the state of Puntland. In so doing he weakened the political influence of elites of his own Majeerteen subclan, which engendered a significant, albeit short-lived, level of trust in his administration from the other clans in the region.93 Moreover, in the early years and in a pattern similar to Somaliland’s, a relatively more efficient tax and revenue collection system was put in place, and courts and prisons were rebuilt that improved security in most of the major towns. There was, as one study noted, enthusiasm for the new regime and its attempts to create functioning institutions, and a sense of freedom allowed civil liberties and independent media to take root.94

However, Puntland’s leaders, and Abdullahi Yusif in particular, quickly demonstrated that they were more intent on reestablishing an authoritarian regime rather than embarking on a genuine grassroots peacebuilding process and state-making enterprise. By the early 2000s, infighting between subclans reemerged; the judiciary and civil service became politicized, administrative corruption intensified; and any elections held by Puntland’s authorities were tightly managed, manipulated, and controlled.95 Ominously, and in a pattern similar to that of the ousted Barre regime, cabinet posts and economic privileges were allocated to loyalists drawn mainly from Abdullahi Yusif’s Omar Mahmoud sub-subclan, and businessmen, including hawala brokers and livestock traders, were forced to pay large fees to operate or pay bribes for access to export licenses which most of the latter allocated along clan lines. The consequence of these increasingly predatory policies was to erode inter- and intra-clan cohesion and undermine the short-lived security arrangements that had sustained peace in the first years of Puntland’s foundation. One resident of Eyfen district explained the state of affairs in Puntland that reflect the authoritarian nature of the Garowe administration, which stands in marked contrast to the situation in Somaliland:

We ask people to pay taxes, but they say there is no security and no basic services, not even clean water. We don’t have a legal framework to tax international non-governmental organizations. [In addition], there is a wide rural-urban divide. As a result, rural areas have no government services or access to remittances from relatives living abroad. The problem is corruption: power is accumulated in the hands of a few powerful clans.96

To make matters worse, Puntland’s leaders had to contend with a strong local ideological rival represented by the militant Islamist organization, al-Ittihad al-Islami (AIAI). The rise in the popularity of al-Ittihad in the early 1990s was a result of the lack of strong governance structures, and the failure of local leaders to deliver law and order in the aftermath of state collapse. At the height of al-Ittihad’s popularity, the forces of the SSDF were simply not able to administer the important port of Bossaso, and consequently AIAI was able to fill the security vacuum and eventually take over the running of the port. It was through their access to the port that they were able to import arms to strengthen their movement and to generate revenue from port taxes which they used as the financial tool with which they recruited followers.97 During my research in Bossaso and Garowe, it was clear that al-Ittihad’s popularity extended beyond Bossaso port. This is because the organization also managed to build strong commercial networks by forging close relationships with influential clan elders in the region and thus were able to wield great economic as well as political influence in civil society. However, this was often accomplished through the use of coercive and violent means. As one resident of Bossaso put it: “[P]eople wanted law and order and better administration, not a religious dictatorship.”98

The Political Economy of State Building: Somaliland and Puntland Compared

Compared to Somaliland, the relatively homogenous Puntland, which is populated primarily by the Majeerteen, a subclan of the Darod, should by some conventional accounts be the stronger state. Yet it is Somaliland – devastated by two waves of violent power struggles involving intraclan and interclan warfare and with a heterogeneous population consisting of many rival clans belonging to three large families – that has achieved better results in reviving the basic institutions of governance. What explains the underlying factors for these divergent developments?

An important reason for this divergence has to do with the war-making phase associated with the state-building enterprise. Both de facto states have experienced intermittent ethnic strife, but only Somaliland president Muhammad Egal was able to defeat his military rivals, which he did after a series of violent conflicts centered on control of the port of Berbera. This factor was crucial to Egal’s success at state building and his efforts at consolidating political rule. By contrast in Puntland, the conflict between Majeerteen elites and Islamists belonging to al-Ittihad continued, albeit with a modicum of accommodation in recent years. In contrast to Puntland, Somaliland has been able to win the ideological battle over potential Islamist rivals. Clan solidarity among the Isaaq in particular has emerged as a strong element in the success of the state-building enterprise. In Puntland, in the context of persistent intraclan tensions between the subclans of the Darod, Islamist identification continues to make inroads despite the fact that the population is more homogenous in terms of clan affiliation.99 To be sure by the mid-1990s, Puntland authorities were able to effectively suppress the military wing of al-Ittihad al-Islami. However, following their defeat by the forces of the SSDF and the loss of control over the lucrative Bossaso port, al-Ittihad altered their vision and strategy. They formally stopped advocating violence and turned toward building support in society through peaceful means. Consequently, they increased their social welfare provisioning including building schools, hospitals, and offering humanitarian services, while simultaneously focusing on expanding their business and trade networks with the Gulf.

In Puntland, by the end of the 2000s, the experiment of indigenous state building that combined a system of clan representational side by side with formal parliamentary rule declined.100 The fragile political system wherein every subclan of the Darod-Harti family would nominate a parliamentarian endorsed by subclan leaders fell apart resulting in the failure to build a viable state in the northeast. An important aspect of this state-building dilemma was that, in addition to facing external threats, the Puntland project’s architects had to contend with the influence of a strong Islamist movement that enjoyed more popularity in civil society than the increasing narrow subclan-centered administration. Indeed, one reason Gerowe effectively ended its efforts at genuine electoral reform to usher in a fledgling democracy as occurred in Somaliland is that it feared the strength of the Islamist opposition. But the central problem that explains the failure of state building in Puntland is, as one analyst put it succinctly, an unresolvable conflict “between the ideal of an indigenous, consensual political system underpinned by a mix of traditional and modern governance institutions, and the reality of a top-down repressive system.”101