Book contents

- The Body Politic in Roman Political Thought

- The Body Politic in Roman Political Thought

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 The Divided Body Politic

- Chapter 2 The Sick Body Politic

- Chapter 3 The Augustan Transformation

- Chapter 4 Julio-Claudian Consensus and Civil War

- Chapter 5 Addressing Autocracy under Nero

- Conclusion

- Works Cited

- Index Locorum

- Index

- References

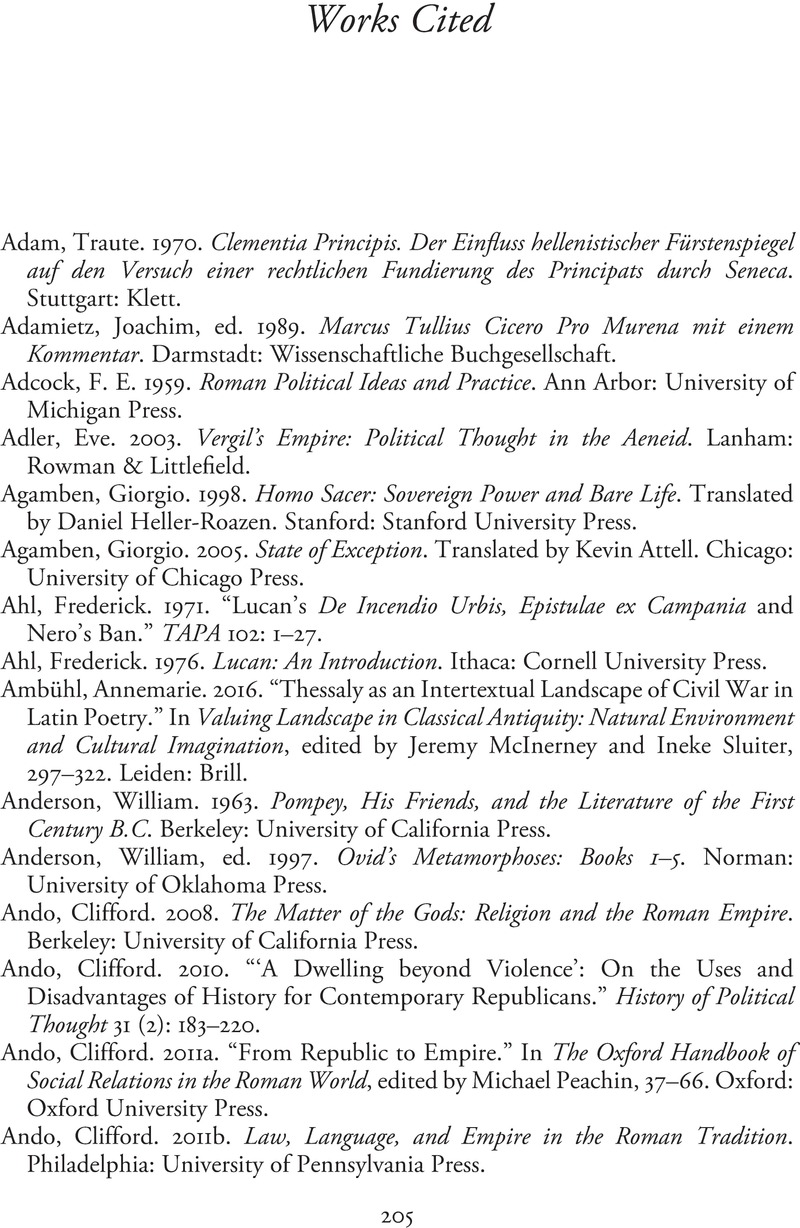

Works Cited

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 February 2024

- The Body Politic in Roman Political Thought

- The Body Politic in Roman Political Thought

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 The Divided Body Politic

- Chapter 2 The Sick Body Politic

- Chapter 3 The Augustan Transformation

- Chapter 4 Julio-Claudian Consensus and Civil War

- Chapter 5 Addressing Autocracy under Nero

- Conclusion

- Works Cited

- Index Locorum

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Body Politic in Roman Political Thought , pp. 205 - 245Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2024