This chapter discusses the existence and reproduction of enslaved families in coffee’s “agrarian empires” during Brazil’s second slavery.Footnote 1 It does so through a case study of the Guaribú fazenda (plantation), located in the Vassouras region of Rio de Janeiro’s Paraíba Valley, which was at the time the world’s most productive coffee region. Guaribú’s history allows us to advance three arguments. First, we demonstrate the ways in which the concepts of “agrarian empires,” “plantation communities,” and “slave neighborhoods” can help us to understand both familial relationships and those that developed between slaves and masters. Second, we show that slave families living on large plantations had better chances than those who lived on smaller estates of remaining together across generations in stable family formations. And finally, we argue that this familial stability enabled Brazil’s “mature slavery,” during which positive birth rates ensured the preservation of enslaved labor even after the end of the Atlantic slave trade in 1850.Footnote 2

The Paraíba Valley in the Context of Second Slavery

The Paraíba Valley was the economic center of the Brazilian Empire (1822–1889). At the end of the eighteenth century, the region was virtually unexploited by the Portuguese, serving mainly as a transit point to the gold-mining region of Minas Gerais. The valley was home to many Indigenous peoples, and landholders ran subsistence farms and a few sesmarias that produced sugar and spirits. Between 1810 and 1840, however, the region’s profile changed significantly. Virgin forest was cleared, most of the Indigenous people were decimated or “tamed,” and almost all property holders began to cultivate coffee with enslaved Afro-descendant labor. This rapid transformation was a consequence of multiple factors. Increasing international demand fueled rising coffee prices; turbulent politics pushed former coffee-producing areas such as Saint Domingue into steep decline, creating new market openings; the region already enjoyed good access to road and harbor infrastructure first constructed to distribute the products of Brazil’s eighteenth-century mining boom; and the valley’s extensive virgin forest reserves and proximity to the slave trade operating out of the port of Rio de Janeiro provided raw materials and labor.Footnote 3 Thanks to all of this, the Paraíba Valley emerged in the 1830s as the largest coffee exporter in the world, creating tremendous wealth.

The coffee plantations of the Paraíba Valley were characterized by highly concentrated land tenure and by patterns of production that privileged extensive slave ownership, to the detriment of smaller producers. Coffee slavery in the Paraíba Valley was from its origins directed toward mass agricultural production to meet high demand within the European and North American industrial consumer markets. It was what Dale Tomich called “second slavery,” differentiated from colonial slavery by its quick pace, high levels of labor exploitation, and close relationship to the international market and industrial capitalism.Footnote 4 In Brazil, the same master class that provided the Empire with its dominant source of political, economic, and intellectual support implemented second slavery even as it helped consolidate the Brazilian Imperial State.Footnote 5 The backbone of the master class comprised large slaveholding landowners, and especially those who commanded hundreds of slaves in the Paraíba Valley.

Many coffee planters owned several fazendas, as well as other related businesses such as commission houses, mule train operators, railroads, and agricultural banks. Furthermore, their power extended to regional and national politics, where the owners’ protégés or relatives held positions as city councilors, local police authorities, senators, civil magistrates, chief police officers, members of the National Guard, etc. Large land-and slaveowners forged extra- and intra-class identities, sharing a slavocratic habitus and valuing European patterns of consumption and behavior.Footnote 6 The city of Vassouras could itself be said to symbolize the master class. Its luxurious built heritage flaunted the power of the region’s leading families; its mansions, like the Big Houses of the coffee fazendas, were often designed by foreign architects and decorated with imported European materials.

The hundreds of thousands of slaves whose labor supported this world had been imported in massive numbers from Africa since the beginning of the nineteenth century. The Atlantic slave trade dictated both the dynamics of master–slave relations and the demography of the slave population until 1850, when the trade was definitively abolished. Even though the number of imported African slaves fell considerably after the 1831 law that officially prohibited the Atlantic traffic, the trade was again strengthened – this time illegally – in the late 1830s and 1840s, due to political pressure from large coffee planters from the Paraíba Valley. The 1831 law was never revoked, but the contraband African trade was openly practiced, with the collusion of Imperial authorities. To give some idea of the scale of this illicit traffic, between 1821 and 1831 some 580,000 enslaved Africans were brought to Brazil, and some 65 percent were destined for the Brazilian Southeast, especially the region’s burgeoning coffee zones. Between 1831 and 1850, the period in which the trade was illegal but still active, this number grew to some 900,000 Africans, of which 712,000, or 79 percent, were destined for the Southeast.Footnote 7 Because of this, the Paraíba Valley would become the Brazilian region with the highest concentration of slaves during the second half of the nineteenth century.

The Case of the Fazenda Guaribú

In order to analyze the slave family in the coffee-based agrarian empires of the central Paraíba Valley, this chapter will focus on the Fazenda Guaribú, which belonged to the former Pau Grande sesmaria, one of the first to be granted in Rio de Janeiro province’s stretch of the Paraíba Valley (see Figure 3.1). Two key factors justify this focus. First, Guaribú is one of the oldest properties of the region, with coffee production dating back to the eighteenth century, when it was still part of the Pau Grande sesmaria.Footnote 8 Second, the Fazenda Guaribú was officially appraised five times during the nineteenth century: first in the postmortem inventories of Luís Gomes Ribeiro (1841), of his wife Joaquina Mathilde de Assunção (1847), and of their son and heir, Claudio Gomes Ribeiro de Avellar (1863); and then later when Gomes Ribeiro de Avellar’s brothers contested their parents’ will and Gomes Ribeiro de Avellar’s share of the total estate was reassessed in 1874 and again in 1885.Footnote 9 Analysis of this documentation allows us to trace how the slave family, in all of its different forms, changed over time and space within the same plantation structure, from its establishment in the 1840s until the crisis of Brazilian slavery in the 1880s.Footnote 10

The owners of the so-called Casa do Pau Grande were the Portuguese brothers Antônio dos Santos, José Rodrigues da Cruz, and Antônio Ribeiro de Avellar. The property comprised seventeen sesmarias – five within Pau Grande, five at Ubá, and seven at Guaribú – and was part of a large business complex that included several fazendas in the Valley and outposts in the commercial centers of Rio de Janeiro, Rio Grande do Sul, and Portugal. In 1797, the family company Avellar & Santos was dissolved and the lands were divided. José Rodrigues da Cruz founded the Ubá fazenda. The inheritance of Antônio Ribeiro de Avellar, deceased in 1798, was left to his widow Antônia, who kept the sesmarias located in Pau Grande. Luís Gomes Ribeiro, António Ribeiro de Avellar’s nephew and son-in-law, acquired the lands that had belonged to Antônio dos Santos and José Rodrigues da Cruz in the area known as Guaribú. In 1811, the partnership between Luís Gomes Ribeiro and his mother-in-law Antônia Ribeiro de Avellar ended, and he went to live in Guaribú with his wife Joaquina Mathilde de Assumpção and their two eldest sons.Footnote 11

Luís Gomes Ribeiro began to acquire slaves exactly at this time (in 1811); thirty years later, in 1841, his postmortem inventory listed 411 slaves in all his properties. The Fazenda Guaribú alone had 244 slaves, 119,000 coffee trees, two residential homes, one storage shed for coffee, a barn, a kiln to make tiles, and various mills to process sugar, manioc, and coffee. Shortly before drafting his will, in 1829, Luís Gomes Ribeiro, aiming to expand the coffee plantation, acquired the Sítio dos Encantos, a relatively small coffee plantation adjacent to Guaribú.Footnote 12 In 1841, Encantos had over 103 slaves, as well as 109,000 coffee trees, a residential house, a barn, a water mill, a fan to dry coffee beans, a mill with pestles, and a mill that ground manioc flour, powered by a water wheel. These properties together formed a large coffee complex – an agrarian empire – that expanded in step with Rio’s Paraíba Valley, the world’s main coffee producer during second slavery and the accelerated rise of global capitalism. In the 1840s, coffee was already Brazil’s most important export, with 100,000 tons exported annually, a figure that doubled in the next decade.Footnote 13 During that same period, the number of slaves disembarked in Brazil went from 34,115 captives in 1810 to 52,430 in 1830.Footnote 14 The vast majority of these forced laborers were destined for the coffee plantations up the mountains from their ports of entry.Footnote 15

In 1841, when his postmortem inventory was initiated, Luís Gomes Ribeiro’s 411 slaves lived in seven senzalas (slave quarters), which were “spread out from one another, tiled, with windows and a kitchen.”Footnote 16 The senzalas housed slaves from both Guaribú and Encantos. Although they spoke different languages and belonged to different cultural systems, most of these slaves forged family bonds, networks of kin and fictive kin, and various forms of solidarity in order to survive the grueling experience of captivity. The postmortem inventory lists thirty-five slave couples, thirty comprised of Africans and five comprised of Africans and crioulos (Brazilian-born Afro-descendants). The slave families were preserved even after the deaths of Luís Gomes Ribeiro (in 1839) and his wife, Joaquina Mathilde de Assumpção (in 1847). It is interesting to note that the family’s strategy for dividing family assets facilitated this preservation: Ribeiro and Assumpção’s son, Claudio Gomes Ribeiro de Avellar, who would become Baron of Guaribú, inherited the bulk of slaves from both Guaribú and Encantos, receiving fifty-six from his father and (years later) another seventy from his mother.Footnote 17 Such continuity, which the historiography indicates was quite common in plantations, provided great stability for many slave families in the Paraíba Valley.Footnote 18 In 1863, when Claudio Gomes Ribeiro de Avellar’s postmortem inventory was initiated, forty-eight couples were recognized and listed for Guaribú, seven at Encantos, and forty at the Sítio das Antas and Boa União, which were new properties acquired by Claudio Ribeiro de Avellar. The inventory also listed various descendants of slaves who had inhabited the fazenda since 1841.

This evidence shows that the slave family was a reality within the rural settings where most Brazilian slaves lived during the nineteenth century. Moreover, they indicate that the slave family had a significant presence in the large coffee plantations. The meaning of this phenomenon has been contested within Brazilian historiography. In the 1990s, the debate became polarized. One view held that the slave family was the product of resistance, a hard-won achievement that allowed captive Africans and crioulos to maintain their social and cultural practices across generations, creating a slave identity that was molded in opposition to the master class.Footnote 19 Another view held that the slave family was a concession, an instrument that allowed slave masters to guarantee peace in the slave quarters and exercise greater control over their captives.Footnote 20 We argue that any approach that aims to produce a single, unitary view of the slave family’s historical meaning may lead to false dichotomies. The slave family could have signified both resistance and coercion. Slave families were nested within broader, extremely unequal configurations of power that disfavored enslaved people; they developed in the midst of structural conditions that facilitated a mode of what we might call slavocratic domination. Yet those families and their meanings varied enormously, depending on a constantly shifting socioeconomic, cultural, and political conjuncture. Broader contexts – such as Brazil’s degree of national political stability or instability, the extent to which international actors actively condemned and combatted slavery, or the volume of the Atlantic slave trade – could influence relationships between masters and slaves, thus transforming the signification of the slave family.

More immediately, the economic cycles of Rio’s Paraíba Valley – and the point at which any particular plantation found itself in the evolution from initial planting to expansion to greatness and decline – had a similar impact on the master–slave relationship.Footnote 21 In the end, master–slave relations and the meanings of the slave family came down to the concrete world shaped by a particular master and by the particular people he or she enslaved. But we cannot lose sight of the broader conditions that shaped those actors’ lives, even when that context was beyond their immediate understanding.

Agrarian Empires in the Coffee-Producing Paraíba Valley

The postmortem inventories of the municipality of Vassouras during the nineteenth century revealed patterns of slave property-holding at once dispersed and very concentrated. Since the end of the 1990s, new research has deepened our knowledge of the coffee-growing area in the Paraíba Valley. These new findings diverge methodologically from previous historiography, which generally divided slave properties into only three categories: small, medium, and large, with the latter generally described as less important because it was numerically the minority.Footnote 22 In Vassouras, a more complex pattern prevailed. There were farmers who owned between one and five slaves, most of whom did not own the land they cultivated and lived together with their captives. Some of those small-time slaveowners had once themselves been captives, before being freed by their former masters. At the other extreme of the pyramid, there were slaveowners with hundreds of slaves, who owned two, three, four, or more plantations. Altogether, our analysis of the collection of 921 postmortem inventories stored in the former Historical Documentation Center of the University Severino Sombra uncovered five categories of owners. Without considering the 2 percent that did not own slaves, the estates can be classified as in Table 3.1.

| Category | Number of Slaves | Percentage in Relation to the Total of Owners | Percentage in Relation to the Total of Slaves in Vassouras |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mini-owners | 1–4 | 16% | 1% |

| Small owners | 5–9 | 39% | 11% |

| Medium owners | 20–49 | 22% | 18% |

| Large owners | 50–99 | 12% | 22% |

| Mega-owners | Over 100 | 9% | 48% |

As we can see in Table 3.1, based on this sample, large and mega owners owned 70 percent of the slaves in Vassouras, which indicates a high concentration of both land and enslaved labor in the region. And these properties determined the conditions in which most captives formed their families.Footnote 23 This fact, as we will see, has important consequences when it comes to analyzing master–slave relationships in Brazil’s most important slave region during the nineteenth century.

Luís Gomes Ribeiro and his son Claudio Gomes Ribeiro de Avellar, Baron of Guaribú, were two of these mega owners. The Baron of Guaribú was in fact the largest of all. With 835 slaves and four farms when he died, in 1863, he built the biggest agrarian empire in the municipality of Vassouras. By agrarian empire, we mean an individual or familial domain – or some combination of both – made up of large landholdings, wherein slaves and land made up more than 60 percent of the proprietors’ wealth. The fortunes of mega-owners were unmatched within their municipalities, their provinces, and even the Brazilian Empire as a whole.

Historian William Kauffman Scarborough coined the expression “agrarian empire” when analyzing the slave-owning elite in the US South, based on nineteenth-century agrarian censuses.Footnote 24 Scarborough used a minimum of 250 slaves to define an agrarian empire in the antebellum United States. In the context of second slavery, however, the forms of concentrated wealth varied from one slave regime to the next, and we thus resolved to elevate Scarborough’s original floor for Rio’s Paraíba basin. Based on the profile of seventy-one mega-proprietors whose postmortem inventories were conducted in Vassouras between 1829 and 1885, we established which among them were at the very top of the slaveholding hierarchy, based on the size of their slave holdings. Forty-seven mega-owners owned between 100 and 199 captives, seventeen held between 200 and 350, and only twelve claimed more than 350.Footnote 25 It thus makes sense, based on the Vassouras inventories, to set the floor for an agrarian empire in the region at 350, though preliminary studies from adjacent regions of the Paraíba Valley such as Piraí, Valença, and Cantagalo suggest that this floor may need to be raised further still. In general, in this coffee-producing area, ownership of an agrarian empire indicated an owner’s extreme wealth and power. Many were made up of several large fazendas, each with between 100 and 300 slaves.

In Vassouras, the following owners could be said to preside over agrarian empires: the Baroness of Campo Belo, the Baron of Guanabara, Ana Joaquina de São José Werneck, Luís Gomes Ribeiro, Manoel Francisco Xavier, Elisa Constança de Almeida, Anna Joaquina de São José, Claudio Gomes Ribeiro de Avellar, Francisco Peixoto de Lacerda Werneck, and the Baron of Capivary. These owners or patriarchs were true rural potentates, with great power and influence both locally and across the province of Rio de Janeiro. Although they were mostly dedicated to the administration and control of their domains, they often used bonds of family, friendship, and political alliance to extend their influence to the rulers of the Empire. Regardless of whether their partisan political leanings were conservative or liberal, they supported the monarchical regime. They formed the core of a dominant class of large slaveholders and landowners, traders and financiers, who linked their social and economic interests to the Imperial political elite, which in turn governed in accordance with the planters’ interests. Together, the political elite and the planter class comprised a new Brazilian aristocracy attached to the Imperial dynasty. Some members of this new aristocracy were granted nonhereditary noble titles. Through this complex network, the new South American Empire depicted itself as the representation of European civilization in the New World.Footnote 26

This agrarian civilization was centered in the large rural plantation houses and their surroundings. Typically, the Big House overlooked one or more rectangular courtyards, where recently harvested coffee beans were left to dry. Initially those courtyards were simply empty patches of earth, but technological advancements led eventually to stone or macadam pavement. The senzalas (slave quarters), usually single-story buildings arranged in lines or squares, were grouped adjacent to the courtyards. The coffee hulling mill, pigsties, animal pens, slave infirmary, and other buildings were also in the so-called functional quadrilateral of the fazendas. The whole complex, and especially the Big Houses – which became more and more refined after the mid-nineteenth century – symbolically expressed the master’s power.

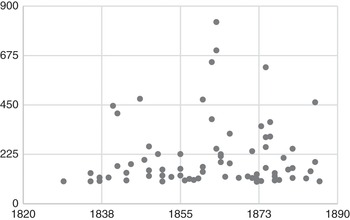

The configuration and nature of agrarian empires were not always the same. They varied over time, depending on where they found themselves in the cycle of economic establishment, development, and decline; their fortunes also fluctuated according to the regional conjuncture and Brazil’s broader economic, social, political, and cultural contexts. Figure 3.2 shows that variation. On a scale of 0 to 900, each dot represents the total number of bondsmen owned by the seventy-one mega-proprietors found in the postmortem inventories of the county of Vassouras during the nineteenth century.

The first mega-proprietor’s inventory for our sample appeared at the end of the 1820s. The estate belonged to Felipe Ferreira Goulart, owner of 102 slaves, whose assets were inventoried in 1829, along with those of his wife, Caetana Rosa de Leme. Mega-proprietors started to become more numerous in the 1830s and 1840s, when the first agrarian empires with more than 350 slaves appeared. A good example is the agrarian empire belonging to Manoel Francisco Xavier, whose inventory was completed in 1840 and listed 446 slaves in his four properties. Manoel Francisco’s fazendas were the site of a famous slave revolt led by Manoel Congo in 1838.Footnote 27 The concentration of slave property in mega-estates reached its apex during the 1860s, with some estates holding over 600 slaves. Among those, besides Claudio Gomes Ribeiro de Avellar and his 835 slaves inventoried in 1863, we also find Claudio’s uncle, Joaquim Ribeiro de Avellar, Baron of Capivary, deceased that same year, who owned the Pau Grande sesmaria and 698 slaves. Claudio Avellar’s brother-in-law, Francisco Peixoto de Lacerda Werneck (Baron of Paty do Alferes) also counted in this elite group when he died in 1862, holding six fazendas in Paty do Alferes and 645 slaves. Such data show that Claudio built his individual holdings within the broader empire of the Ribeiro de Avellar clan, based in Paty do Alferes, where he divided local power with his relatives from the Lacerda Werneck clan.Footnote 28 The maximum number of slaves found in postmortem inventories dropped below 400 in the next decades, except for the disputed inventory of Claudio Gomes Ribeiro de Avellar.

Inventories are appraisals of assets, carried out at the time of an individual’s death. For that reason, it is reasonable to assume that the majority of inventories reflected moments when a person’s businesses were already well-established, at a plateau, or even in decline.Footnote 29 But this was not always the case. Aside from premature death, which was unusual, an individual’s life cycle could diverge from that of their businesses. This is exactly what we can observe in the inventory of Luís Gomes Ribeiro, the first patriarch of the agrarian empire of Guaribú, whose businesses were still on the rise during the 1840s, when coffee was in growing demand on the international market.

In the 1850s, Luís’ son Claudio Gomes Ribeiro de Avellar’s lands, which were almost contiguous to one another, totalled 3,156 hectares, equivalent to 31.5 million square meters, or 7,795 acres. In comparative terms, his empire was equivalent – both in relation to land area and to number of slaves – to that belonging to John Burnside, Louisiana’s biggest sugar producer in 1858. At that time, Burnside’s agrarian empire consisted of five contiguous plantations, totaling 7,600 acres of land, with a labor force of 1,000 slaves.Footnote 30

Returning to Figure 3.2, we can see that only four inventories indicated possessions greater than 350 slaves in the 1870s and 1880s. Two of them were the aforementioned reassessments of the Baron of Guaribú’s estate, which remained in dispute until the 1890s. His legacy continued to represent the largest concentration of slave property in the region. In 1874, his estate’s 621 slaves far exceeded the 353 slaves listed among the properties of Eufrásia Correia e Castro, Baroness of Campo Belo (who died in 1873), and the 372 slaves in the 1875 inventory of José Gonçalves de Oliveira Roxo, Baron of Guanabara. In 1885, the 462 slaves bequeathed by the Baron of Guaribú were still unparalleled. This information matters because it shapes our analysis of the slave family, which was circumscribed within a specific form of property accumulation (involving wealth, land, and labor) that occurred in the southern Paraíba river basin, typified by the region’s agrarian empires.

Plantation Communities

As we have seen, most slaves in the Paraíba Valley lived on large fazendas that were part of mega-properties or agrarian empires. On those fazendas, a larger number of slaves entailed a greater proportion of enslaved women and a more even gender balance, which made it easier for slaves to pair off and create families. Because so many slaves belonged to the same owner, and because they were often able to establish bonds and lines of communication among contiguous fazendas, enslaved people could establish a wide spectrum of social ties, which also made family formation more viable. Furthermore, after the end of the Atlantic slave trade in 1850, an increase in the proportion of enslaved women and the need to produce new laborers within the plantations encouraged masters to strategically promote slave families.

For slave families, the senzala was a foundational space. On large fazendas, senzalas were single-story wattle and daub houses, with thatched roofs that were often converted to tile after 1850, an adjustment that greatly reduced their temperature and humidity. Their floors were mostly beaten earth, though they could sometimes have finished flooring. Most were divided into cubicles of 9–12 meter square. Each cubicle had a door that opened onto the courtyard, and a rare few had windows. Ventilation was generally provided by wooden-barred openings at the juncture of the walls and roof. Each cubicle housed a family or a group of same-sex slaves. In some cases, especially in fazendas with numerous slaves, the senzalas could themselves form a three- or four-sided enclosure, as was the case on the fazendas Santo Antônio do Paiol and Flores do Paraíso, both in Valença.Footnote 31 Slave families formed in such spaces, and there they lived, under the daily oversight of foremen, supervisors, and masters.

Daily conflicts and negotiations between slaves and masters were an inherent and permanent feature of the slave system. As part of this process, enslaved people forged identities and carved out spaces for autonomy, which were sometimes expansive and sometimes more constricted; in these ways, enslaved people left their mark on Brazil’s imperial culture and society. Some historians use expressions such as slave communities or senzala communities to describe the relationships forged among slaves, their nuclear families, and their extended relatives. This denomination aims to highlight slave autonomy and the sense of common identity that slaves created within captivity, in clear opposition to their masters’ domination.Footnote 32 According to Flávio dos Santos Gomes, such slave communities communicated with other senzala communities, freedpersons, peasants, mocambos (runaways), and quilombolas (inhabitants of maroon communities) creating what he has designated a “Black countryside.”Footnote 33

Yet this focus on autonomy, which was the hallmark of the historiography of Brazilian slavery written in the 1980s and 1990s, should not obscure the fact that these autonomous spaces were forged within structures of power and political, social, economic, and cultural conjunctures that were highly unfavorable to slaves.Footnote 34 These structures, which changed considerably over time, set the limits of slave agency. Such boundaries were determined, for example, by the greater or lesser presence of Africans among a given slave population; by the size of the property where slaves lived and worked; or by the manumission practices that were the norm within any given property or region. The class relationships between slaves and owners were thus elastic and turbulent. Without underestimating the importance of the bonds created among slaves or their struggles for autonomy and liberty, we argue that such spaces of agency were circumscribed by the slave regime.

In order to understand the structural asymmetry of master–slave relationships at the local level, we propose in this chapter that the expression “plantation community” is more useful than “slave community” or “senzala community.” In doing so, we not only contest the notion of a community as a harmonious group; we also conceive of slaves’ actions as inevitably connected to their masters’ dominion. By taking into account only the agency and resistance of the slaves, the “slave community” concept loses some of its analytic capacity. The “plantation community” concept also usefully captures the integration of slaves’ workspaces and their living environments. Slaves did not themselves organize the senzalas, which were contiguous to the rest of the plantation and ordered according to its larger needs and structure. The formation of plantation communities in the coffee-producing areas of the Paraíba Valley was essential to the process through which any given group of slaves was transformed into a collective labor force, creating a structure of domination that endured for many decades.

In the coffee production zone of the Paraíba Valley, plantation communities were a sine qua non for high productivity and profit. From the toll of the morning bell before sunrise to the final count and slave inspection at the end of a day’s toil, the captives’ work was mixed with various social activities – meals, rest, chatting, singing, dancing, praying – that could result in new forms of organization, sociability, and family. Enslaved people also usually had Sundays and holidays free, time they spent raising small animals and vegetables to consume or sell to their masters. Work, family, and community were not separated spheres: the result was a dense net of social relations with the slave family at its core. Effectively, the largest slave cohorts – even those recently trafficked from Africa – were never simply groups of people brought together to work. They comprised a plantation community, involving forms of sociability, cultural links, spiritual encouragement, and family life that went well beyond the strict mandates of commodity production. Slave labor could only reach its full productive capacity if it was part of such a plantation community, in which the slave family played a fundamental role. This was true even at the height of the international slave trade, when the high number of men among newly imported Africans produced a significant gender imbalance among slaves. Even under these adverse conditions, the few African and crioula women who were present anchored stable relationships and families within the plantations’ borders. After 1850, when the international slave trade was abolished, a more equal gender balance among the slaves facilitated family formation.

In short, the concept of a plantation community aims to break the false dichotomy that has dominated the historiography of the slave family in Brazil, which imposes an unnecessary choice between viewing family formation as an act of slave agency and resistance or viewing it as a form of slavocratic oppression. This does not mean that we should for a moment ignore the profound contradictions that placed masters and slaves in opposition, evident in the slaves’ many acts of resistance. If slave revolt had not been endemic to the world of slavery, that world would not have been what it was. In situating the slave family as a component of a plantation community, we instead wish to accentuate the slave family’s contradictory character and that fact that it was – like other aspects of fazenda life, in all their specificity – subject to a constantly shifting balance of power between masters and slaves, both locally and globally.

Nothing demonstrates this asymmetrical balance of power better than the masters’ postmortem inventories. These express and expose all of the slave–master relationships’ various temporalities and dimensions: the juridico-political norms that consecrated and legitimated slave property; the intimate life of masters and their families; the spiritual and affective realm evident through requests for mass to be said for the souls of family members, godchildren, and slaves; and a material world that included objects, assets, lands, animals, and (inevitably) slaves. Slaves appear in inventories with names, ages, origins, skills, behaviors, family ties, and material appraisals. At one point we might see a reference to an old man, broken and worthless; later we encounter a woman appraised with her newborn baby or child. Further on, we find a note about so-and so, son of such-and-such, appraised individually but listed right below his parents, in implicit recognition of the unity of the slave family. This listing order was common to the majority of inventories and expressed the contradiction inherent in the slave family: enslaved people were joined together by recognized ties, but each was also marked with an individual market value.

The masters’ inventories, as snapshots of their time, allow us to perceive gradual mutations and shifts in the slave family, which was shaped by the conditions of each historical period. The Guaribú case is especially valuable in this sense, because it grants us access to so many slave appraisals in a single site. Let us shift, then, to setting the scene of the Guaribú plantation community in the time of Luís Gomes Ribeiro.

The Slave Family in the Plantation Communities of the Fazenda Guaribú

The second patriarch of Guaribú, Claudio Gomes Ribeiro de Avellar, began acquiring slaves even before he inherited the Fazenda Guaribú and the Sítio dos Encantos. In 1831, he was already among the recipients of the assets of his father, Luís Gomes Ribeiro, and he insisted in receiving his payment in lands and slaves, indicating that he was already established as a landowner-capitalist by the time he was around thirty years old. The list of 835 slaves included in his 1863 postmortem inventory indicates that Claudio depended heavily on illegal slave traffic between 1831 and 1850 to expand his businesses; many slaves were from a wide range of African ports, and they were too young to have come before 1831. But that was not enough: the Baron of Guaribú also made heavy use of the internal slave trade to stock his fazenda workforce, listing slaves from Bahia (thirty-four), the city of Rio de Janeiro (eleven), Iguaçu (one), and Minas Gerais (three). He also benefitted, of course, from the natural growth allowed by the establishment of stable families during the mature stage of coffee slavery.Footnote 35

Among the 618 slaves whose provenance was listed (75 percent of the total), 52.2 percent were crioulos (Brazilian-born) and 47.8 percent were Africans. Among the Africans, 15 percent were women, 32.5 percent of whom were married. Among the 85 percent of Africans who were men, 31.2 percent had spouses. Among crioulos, the marriage rate dropped for both men and women; each gender had only five married people. The average age of crioulos, however, was much lower than that of Africans, and many were too young to marry. The African women were between forty and seventy-one years old; the African men were between forty-seven and seventy-one. Among crioulos, the youngest were one year old, the oldest woman was sixty-one, and the oldest man was fifty-nine. All in all, 24.1 percent of the estate’s slaves were married. On the basis of this evidence, we can consider Guaribú a mature plantation community in the early 1860s.

In order to analyze family structures on these properties, we have defined any link that appears on the inventory lists as a familial tie. Our intention was to accommodate the full range of ways in which enslaved people organized their families. Yet it is important not to forget that the number of slave families would be much higher if the inventories had included informal unions, which were unregistered and unsanctioned but quite common in the daily life of plantation communities.

Among the slaves listed in Luís Gomes Ribeiro’s 1841 inventory, 243 lived and worked in the Guaribú property and 168 in the Sítio dos Encantos. Between the 1820s and the 1840s, when the demand for slave labor to structure the coffee economy in the Paraíba Valley was very high, large slaveholders generally preferred African-born slaves between sixteen and forty years of age, who were esteemed for their physical strength and aptitude for work. This created a great imbalance between male and female slaves and led to a very unstable period for slave families. Even so, as was noted earlier, an analysis of slave families on the Fazenda Guaribú under Luís Gomes Ribeiro’s administration indicates the existence of thirty-five slave couples, five comprised of African and crioulo partners and thirty comprised exclusively of Africans. Among the unions recognized in Ribeiro’s inventory, thirteen couples had parented a total of twenty-one crioulo children, ranging in age from newborn to eight years of age, which suggests that a policy of encouraging family formation had existed for at least a decade in Guaribú. Such a policy could have taken many forms: masters might have set aside cubicles within the senzala for family use, held collective Catholic weddings for slave couples, or simply acknowledged extant stable unions.

One of the crioulo–African couples on Luís Gomes Ribeiro’s plantation was made up of Francisca, an eighteen-year-old crioula, and Custódio, a twenty-four-year-old from Rebolo, who were the parents of three-year-old Brás and three-month-old Cândida. African couples included José Maria from Calabar, forty, and Felizarda from Mozambique, nineteen, who were the parents of seven-year-old Ignês; and Romualdo, thirty-five, and Thereza, twenty, who were both from Mozambique and the parents of five-year-old Philismina and one-year-old Sebastião. The oldest married man was eighty (Francisco from Benguela), and the oldest woman was sixty (Ana, also from Benguela). The youngest married men and women were twenty-four and sixteen respectively, which suggests that enslaved women married at a younger age. It did not seem, however, that the older African men in our sample enjoyed any special privileges when it came to family formation.

On both the Guaribú and the Encantos properties, we found a significant number of African boys and girls with no known family connections. This suggests that they were separated from their families, whether when taken captive in Africa, during the middle passage, or at the point of sale on Brazilian territory. Such were the likely histories of Simplício from Cabinda, ten, and Bernardo from Congo, nine, who were placed at the Sítio dos Encantos, and also of Ninfa from Angola and Aleixo from Congo, both eleven, who worked at the Fazenda Guaribú. Even in these cases, however, a lack of blood relations did not necessarily preclude slave children from forging affective familial ties or other forms of solidarity within the plantation community. Over twenty years later, in 1863, the Baron of Guaribú’s slaves were distributed in the following manner: 441 slaves at the Fazenda Guaribú, 315 at the Sítio Antas, seventy-three at the Sítio dos Encantos, and six at Boa União.Footnote 36 These numbers, when compared to those found in the inventories of the Baron’s parents, suggest that Guaribú and Antas were very productive properties. With regard to slave families, there were eighty families at Guaribú, fifty-two at Antas, seven at Encantos, and none in Boa União in 1863. Much of the family life that these men, women, and children experienced played out in the space of the senzala. To shelter the largest concentration of slave labor in the municipality of Vassouras, the Baron had two senzalas in Guaribú, one with twenty-five cubicles and another with twenty-four, as well as a separate senzala for household slaves; he also had a senzala with twenty-two cubicles in Encantos, as well as five senzalas in Antas and Boa União, divided into between three and twenty cubicles.

The figures in Table 3.2 indicate that Guaribú, Antas, and Encantos had a stable plantation community, because they show three generations of family members living together. In Guaribú and Antas, the slave family was at the base of this stability, especially if we take into account the large number of slaves who lived amidst relatives and the children who were born in captivity, who were numerous enough to result in a natural increase in Guaribú’s enslaved population.

| Family Types | Guaribú | Antas | Encantos | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1863 | 1874 | 1863 | 1874 | 1863 | 1874 | |

| Couples without children | 25 | 19 | 12 | 7 | 1 | 0 |

| Mothers/grandparents with children/grandchildren | 17 | 17 | 8 | 10 | 0 | 2 |

| Fathers/grandparents with children/grandchildren | 0 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Couples with children and/or other relatives | 38 | 14 | 28 | 24 | 6 | 4 |

| Total families | 80 | 53 | 52 | 55 | 7 | 6 |

Other features reinforce the impression that these properties functioned as a plantation community. First, families were long-lasting. In the 1863 inventory, there were three families in their third generation, which means that at least twenty-eight children were living with their grandparents in captivity. In the 1874 appraisal, after the Baron of Guaribú had been deceased for more than a decade and the buying of new slaves had almost ceased, there were six third-generation families with fourteen third-generation children. A family’s longevity could extend to a fifth generation. Nazário and his crioulo son Venceslau, for example, worked on the Sítio dos Encantos. In 1863, Venceslau was married to Fortunata from Monjolo. He was father to Emília, Teolinda, Ventura, and Alexandrina, as well as grandfather to Emília’s children, Fortunata and Faustino. The family probably lived in one or two of the Encanto senzala’s twenty-two cubicles. In 1885, Nazário had died, but his great-granddaughters Fortunata and Alexandrina had already given birth to five free children, Manoel, Cecília, Maximiliano, Felisberta, and Ludovica.

Secondly, family structures varied across time, and slave households often generated new family units. This process reinforces the impression that these were stable families but also suggests that the slave family was a dynamic structure, in constant transformation. Enslaved people recognized the family units among them and sought to ensure their permanence through internal mechanisms of control, such as those that prohibited incest and infanticide or protected orphans. Finally, the advanced age of many of the African-born slaves was a clear sign that the plantation community was well established and had become a stable space where enduring relationships could be forged among slaves, freedpersons, free workers, and masters.

The family of Romualdo and Thereza, both from Mozambique, allows us to explore this dynamic. As was mentioned earlier, Romualdo was thirty-five and Thereza was twenty in 1841, when they were listed as Luís Gomes Ribeiro’s property. They had two children, five-year-old Felisbina and one-year-old Sebastião. The family remained together even after Ribeiro’s death, as seems to have been common in estates with large concentrations of slave property.Footnote 38 Twenty-two years later, in 1863, the couple had had another son, Marcelino, who had been born one year after his brother Sebastião. Romualdo had already died, but his forty-two-year-old widow Thereza was the grandmother of Daniel (eleven), Cândida (nine), Bernardino (nine), and Romualdo (three), who was his grandfather’s namesake. Unfortunately, the inventory did not reveal those children’s parentage. Nonetheless, it is clear that this family, like many others within that plantation community, remained together for over forty years (1841–1885), having moved from Guaribú to Antas sometime between 1874 and 1885.

The resilience of slave family dynamics in this plantation community emerges when we use postmortem inventories to trace the fates of children who lost their mothers. Anselmo, from Mozambique, remained with his crioulo children Helena and Anselmo after the death of his wife. Nazario, also widowed, raised his son Venceslau, who later married Fortunata. They had four children, Alexandrina, Emília, Theodora, and Ventura. When Alexandrina gave birth to Faustino and Fortunata, Nazario’s great-grandchildren, a family that had once been reduced to father and son extended to a fourth generation. The estate appraiser’s annotations in the Baron of Guaribu’s will suggest that the stability of the slave family was understood as an organizing principle, not only among slaves but also among slaveowners and legal representatives: he listed the crioulos João (twenty-seven), Idalina (twenty-five), Rosa (twenty-three), and Raphael (twenty-one) as orphans despite the fact that they were adults, in clear recognition that they were siblings who belonged to the same family and ought to be kept together when the estate was partitioned among its heirs.

Significantly, plantation communities within the same agrarian empire were not isolated from one another. The curtailment of free circulation was of course a constitutive element of enslavement and an important instrument of control in the hands of slaveowners. But there was still carefully monitored movement among properties that were part of the same coffee complex. Archival documents such as the journal of the Viscountess of Arcozelo, for example, indicated that slaves often moved among properties in order to carry out specific tasks during periods when work rhythms were most intense.Footnote 39 Similarly, slaves with specialized skills were sometimes temporarily reassigned to the raw labor of coffee cultivation. Slaves were frequently sent on errands, carrying messages and goods or making purchases; they were also sometimes permitted to date or to attend parties, baptisms, or collective weddings. The Baron of Guaribú’s will, drafted on August 26, 1863, a few days before his death, shows us that the movement within a coffee complex could involve an entire family, lending further support to the argument that the family was the basis for labor stability and a sense of common purpose in plantation communities. Claudio Ribeiro de Avellar noted:

The following slaves are now present at the Fazenda Guaribú, although they belong to the Fazenda das Antas and are part of that place: Marçal, a carpenter, with his wife, children and brothers; Faustino Inhambane, a construction worker; Joaquim, a construction worker; Inhambane and his family; Albério Inhambane; Thomas Caseiro; Modesto Caseir; Luiz Inhambane, a muleteer, with his family; Matheus, a muleteer, Messias, a muleteer; Antonio Moçambique, a muleteer; Simão Crioulo; Germano Inhambane, a cook; and Sabino, a muleteer.Footnote 40

Claudio Ribeiro de Avellar’s instructions were clear: after finishing their tasks at Guaribú, the slaves should return to their place of residence, the Antas plantation community. Regarding slave mobility, the Baron of Guaribú also included another interesting directive: he asked that his sons Manoel, Luís, and João Gomes Ribeiro de Avellar, heirs of the Antas and Boa União properties, also select 120 slaves from Guaribú as part of their inheritance. In his own words: “I leave to Manoel Gomes Ribeiro de Avellar and his two brothers, Luís and João, one hundred and twenty slaves from the Fazenda Guaribú, which Manuel shall choose at his discretion.” The order was carried out, and three Guaribú families were inventoried at the Fazenda das Antas in 1885. The case of Matheus Moçambique (fifty-one years old) and Feliciana – parents to Manoel Lino (sixteen), Emerenciana (eleven), the twins Magdalena and Helena (nine), and Feliciana (three) – stands out. In 1885, when he was listed as part of Antas’ enslaved property, Matheus was eighty-five, and the siblings Manoel Lino and Helena were the only relatives who were no longer part of the family unit. We cannot say why or at what moment between 1863 and 1885 the family was transferred. But when Matheus was chosen by the Baron’s heirs he was certainly very elderly. The will did not require that the heirs respect family units in choosing their 120 slaves. Nevertheless, Matheus was sent along with his family, despite the fact that he was no longer able to work and had virtually no market value, a fact that highlights the importance of the slave family within the plantation community.

Whether they were sent to another fazenda to work or to participate in religious celebrations, funerals, or collective slave baptisms, the fact is that captives’ spatial experience extended far beyond the boundaries of the plantations where they lived. Even when moves were permanent, like those previously described, the slaves and families we could follow in Gomes Ribeiro de Avellar’s inventories were transferred from one community to another but did not go to an entirely unknown or indecipherable space (though this could and did happen in other sales or when slaves ran away). Whether or not their masters recognized it, enslaved people who moved among properties that formed part of the same agrarian empire created webs of solidarity and ties of love and marriage, and they also experienced intrapersonal conflict. In this way, they created every day what Anthony Kaye has referred to as “slave neighborhoods.”Footnote 41 Yet Kaye’s concept of a “slave neighborhood” rejects the prima facie assumption of slave autonomy and harmonious collaboration, seeking also to take into account the slave–master relationship; there is no slave neighborhood without a larger neighborhood largely controlled by masters. Slave neighborhoods were at once individual and collective creations; they were places of work and of leisure, of dispute and of collaboration, of spiritual encouragement and of brutal exploitation, which expanded and contracted depending on both internal and external factors. Slave neighborhoods were home to a wide range of relationships among their social actors, which included field slaves, domestic slaves, masters, free workers, and more. We argue in this chapter that the concept of the slave neighborhood also has an important territorial dimension; its various spatial components – including roads, forest paths, neighboring fazendas, nearby cities, escape routes, and ritual spaces – were always interspersed within and enveloped by a master’s neighborhood.

Conclusion

The analysis of the family ties established by slaves in the Baron of Guaribá’s agrarian empire between 1840 and 1880 allows us to reflect more broadly on the importance of the slave family in creating plantation communities in the Paraíba Valley’s coffee regions. The profile of the slave family changed significantly with the end of the Atlantic slave trade, when a more even gender balance allowed for considerable growth in the number of slave families. This denser family formation was a fundamental characteristic of “mature slavery” in Brazil, which we define as the point at which plantation structures were well established and stable and when slavery came to be sustained through natural increase without a need for imported slaves. Within plantation communities, slave families – with their forms of sociability, religious beliefs, affective ties, disputes, and quarrels – were fundamental to the process through which slaves became an effective collective labor force. The fact that the same families stayed together on the same plantation over many generations demonstrates their structural importance to the slave system as a whole. What is more, slaves’ integrated spatial experiences were not limited to plantation communities; they also participated in Kaye’s larger “slave neighborhoods,” the fluid boundaries of which extended the unequal symbiosis inherent in the plantation community to broader regional geographies.